Abstract

It is well known that local anesthetics have a broad spectrum of pharmacological actions, acting as nerve blocks, and treating pain and cardiac arrhythmias via blocking of the sodium channel. The use of local anesthetics could reduce the possibility of cancer metastasis and recurrence following surgical tumor excision. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the inhibitory effect of lidocaine upon the invasion and migration of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 6 (TRPV6)-expressing cancer cells. Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, prostatic cancer PC-3 cells and ovarian cancer ES-2 cells were treated with lidocaine. Cell viability was quantitatively determined by MTT assay. The migration of the cells was evaluated using the wound healing assay, and the invasion of the cells was assessed using a Transwell assay. Calcium (Ca2+) measurements were performed using a Fluo-3 AM fluorescence kit. The expression of TRPV6 mRNA and protein in the cells was determined by quantitative-polymerase chain reaction and western blot analysis, respectively. The results suggested that lidocaine inhibits the cell invasion and migration of MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells at lower than clinical concentrations. The inhibitory effect of lidocaine on TRPV6-expressing cancer cells was associated with a reduced rate of calcium influx, and could occur partly as a result of the downregulation of TRPV6 expression. The use of appropriate local anesthetics may confer potential benefits in clinical practice for the treatment of patients with TRPV6-expressing cancer.

Keywords: lidocaine, cancer cell, invasion, migration, TRPV6

Introduction

Although there are currently a number of antitumor treatments, surgery remains the most effective for use in solid tumors. It has been suggested that tumor cells may be released from the primary tumor into the vascular and lymphatic circulation through tumor manipulation during surgery (1), ultimately resulting in an increased risk of distant metastases and recurrence. Mortality in cancer patients is mainly caused by metastases. The invasion and migration of tumor cells are critical steps during tumor metastasis (2). In order to become invasive, tumor cells must acquire capacities that enable enhanced migration through, and proteolysis of the extracellular matrix. The ability of migration is a prerequisite for a cancer cell to escape from the primary tumor and be released into the circulation (3).

Calcium (Ca2+), as a second messenger, is one of the critical regulators of cell migration. Previous findings have shown that Ca2+ influx is essential for the migration of various cell types, including tumor cells (4,5). Calcium channel components, which are responsible for altered calcium signaling in cancer cells, include the store-operated calcium (SOC) channels, calcium release-activated calcium channel protein 1 (ORAI1) and a number of transient receptor potential (TRP) channel family members. TRP subfamily V member 6 (TRPV6) (also known as ECAC2, CaT1 and CaT-like) is a member of the TRP channel family, and it has particularly high selectivity for Ca2+, as well as constitutive activity (6). Expression of TRPV6 mRNA and protein has been detected in ovarian cancer and other cancer types, such as breast, prostate, thyroid and colon cancer (7). Dhennin-Duthille et al (8) reported that selective silencing of TRPV6 inhibited the migration and invasion of breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, as well as MCF-7 cell migration. It has been suggested that TRPV6 has the potential for diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic use in human breast and prostate cancer (6,8–11).

Certain studies have suggested that the use of regional anesthesia can reduce the possibility of cancer metastasis and recurrence following surgical tumor excision, at least in specific tumor types, such as breast and colorectal cancer (12,13). Local anesthetics are known to block the voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSC) in excitable cells, and have been proven to have the effect of inhibiting tumor cell invasion and migration in vitro (14,15). However, the evidence of local anesthetics for the inhibition of tumor progression through VGSC is limited (1). Local anesthetics not only block VGSC at concentrations that are much lower than clinical concentrations during regional anesthesia, but they also block potassium (K+) channels and Ca2+ channels.

Lidocaine, the most commonly used local anesthetic, is considered to effectively inhibit the invasive ability of tumor cells at the concentrations used in surgical treatment (16). The present study therefore investigated the inhibitory effect of lidocaine upon the cell invasion and migration of TRPV6-expressing cancer cells, including breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, prostatic cancer PC-3 cells and ovarian cancer ES-2 cells. The study also investigated the expression of TRPV6 mRNA and protein in the cells subsequent to the treatment with lidocaine to determine whether lidocaine inhibits TRPV6-expressing cancer cell invasion and migration via TRPV6 downregulation.

Materials and methods

Major reagents

Lidocaine hydrochloride with a purity of 2% was purchased from Xinzheng Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). The concentrations of the lidocaine local anesthetic are expressed in molarity (mM) instead of percentages (%): 2%≈74 mM, 0.27%≈10 mM and 0.027%≈1 mM (17).

Cell culture

Breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, prostatic cancer PC-3 cells and ovarian cancer ES-2 cells were obtained from and stored at the Molecular Medicine and Cancer Research Center, Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone; GE Healthcare, Logan, UT, USA), 50 µg/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

MTT assay

Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. Briefly, the MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells were seeded into 96-well plates (1×104 cells/well), and treated with fresh serum-free RPMI 1640 medium and different concentrations of lidocaine (0, 10 and 100 µM, and 1, 2, 5 and 10 mM), respectively. Once the cells had been incubated for 24 h, 200 µl MTT (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China)-containing medium (0.5 mg/ml, diluted with fresh serum-free RPMI 1640 medium) was added into each well, and the cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Finally, the MTT-containing medium was removed and 150 µl dimethyl sulfoxide was added per well. The optical density (OD) was measured using an iEMS Analyzer (Labsystems IEMS MF Type 1401; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at a wavelength of 570 nm. The percentage of viability was calculated using the following equation: Viability (%) = (OD treatment group / OD control group) × 100.

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was measured using a wound healing assay. Briefly, the MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells were seeded into 6-well plates (1×106 cells/well). Once the monolayer of cells had reached 100% confluence in the 6-well plates, the cells were wounded with a sterile 10-µl plastic micropipette tip to generate a clean scratch wound across the center of the well. The floating cells were washed away and 2.5 ml fresh serum-free RPMI 1640 medium was added together with different concentrations of lidocaine (0 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM and 1 mM) in each well. The 6-well plates were then placed in the CO2 incubator to allow the cells to migrate. The wound closure was assessed at the 24-h time point by microscopic examination using research inverted microscope IX83 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Five randomly selected points along each wound were marked, and the shortest horizontal distance of the wound area was measured. The migration distance of the treated cells was determined as the difference between the shortest distance in the initial wound and the shortest distance measured at the 24-h time point.

Cell invasion assay

Cell invasiveness was evaluated using Transwell chambers, which incorporated a polycarbonate filter membrane (Coring Costar, Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA). The polycarbonate filter membrane at the bottom of the upper chamber was coated with 50 µl Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C prior to use. The MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells were re-suspended with fresh serum-free RPMI 1640 medium and different concentrations of lidocaine (0 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM and 1 mM) and seeded in the upper chambers (200 µl; 1×105 cell/well), respectively. The bottom chamber was filled with RPMI 1640 medium enriched with 10% FBS. The cells were incubated in the CO2 incubator for 24 h. The cells that did not penetrate the polycarbonate filter membrane were removed using a clean cotton swab. The cells on the lower surface of the polycarbonate filter membrane were fixed with 70% ethanol for 15 min and then stained with azure eosin methylene blue for 10 min. The cells from five randomly selected fields were counted by light microscopy.

Measurement of intracellular-free Ca2+ [Ca2+]I

Ca2+ measurements were performed using a Fluo-3 AM fluorescence kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells were seeded into 6-well plates (1×106 cells/well). The cell medium was replaced by 2.5 ml fresh serum-free RPMI 1640 medium with different concentrations of lidocaine (0 and 100 µM), and then placed in the CO2 incubator for 12 h. The medium in each well was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS buffer (without CaCl2 and MgCl2), prior to the Fluo-3 AM fluorescence probes (0.5 µM) being added to each well. The cells were incubated with the probes for 60 min and protected from light. Following the removal of the Fluo-3 AM dye-containing medium, the cells were incubated in Tyrode's solution (145 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaOH, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES and 10 mM glucose; pH 7.4) for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were then harvested and resuspended with Ca2+-free Tyrode's solution. [Ca2+]I was analyzed using a flow cytometry method according to the manufacturer's instructions (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Quantitative-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis

The MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells were seeded into 6-well plates (1×106 cells/well). Subsequent to being left untreated or treated with 100 µM lidocaine for 12 h, the expression of TRPV6 mRNA was analyzed by quantitative-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from monolayer cells using TRIzol reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions and quantified by spectrophotometry at a wavelength of 260 nm. First-strand cDNAs were synthesized from 5 µg total RNA in a 20-µl reaction using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), reverse transcriptase, oligo(dT) primers and Taq DNA polymerase (SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II; Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). Reverse transcription-qPCR was performed in a CFX96 Real-Time PCR machine (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The primers used were as follows: TRPV6 forward, 5′-TTTCCTGGGTGCATCAAAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACGTACATTCCTTGGCGTTC-3′; and GAPDH (reference gene) forward, 5′-CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT-3′. The reaction was initiated with denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 60 sec (annealing), a terminal extension step at 95°C for 10 sec and a final holding stage at 4°C. Relative TRPV6 mRNA expression was defined as the ratio of TRPV6 gene expression to GAPDH expression. The experiment was repeated three times.

Western blot analysis

The MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells were seeded into 6-well plates (1×106 cells/well). After being left untreated or treated or with 100 µM lidocaine for 12 h, the protein expression of TRPV6 was assessed by western blot analysis. The cells were lysed with lysis buffer and then centrifuged (14,000 × g for 15 min) for the extraction of total proteins. The concentration of total proteins was analyzed using a bicinchoninic acid assay. Protein samples were separated by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and then electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The PVDF membrane was blocked for 2 h at room temperature in TBS-Tween 20 (TBST) buffer containing 5% skimmed milk, washed with TBST three times (10 min each) and incubated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse TRPV-6 antibodies (1:500 dilution; cat. no. ab117875; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and mouse monoclonal β-actin antibodies (1:10,000 dilution; cat. no. AA128; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), respectively. Subsequent to being washed with TBST three times (10 min each), the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (H+L) secondary antibody (1;4,000 dilution; cat. no. A0208; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at 37°C for 1 h. Protein signals were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence 32 reagent (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and quantified by densitometry using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 20.0 for Windows software (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were analyzed using a repeated measure analysis of variance. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Lidocaine decreases cell viability at high concentrations

To observe the inhibitory effect of lidocaine on the viability of TRPV6-expressing cancer cells (MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2), the OD of cells treated with different concentrations of lidocaine (0 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM, 1 mM, 2 mM, 5 mM and 10 mM) was measured and the percentage viability was calculated. As shown in Fig. 1A, lidocaine was able to significantly decreased cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner. However, lower concentrations (≤1 mM) of lidocaine exhibited no marked cytotoxicity. The study subsequently aimed to determine whether lidocaine at lower concentrations (10 µM, 100 µM and 1 mM) inhibited the invasion and migration of TRPV6-expressing cancer cells.

Figure 1.

(A) Cell viability of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 6-expressing cancer cells (MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells) after treatment with a series of concentrations of lidocaine (0, 10 and 100 µM, and 1, 2, 5 and 10 mM) for 24 h. The fluorescence curves of the (B) MDA-MB-231, (C) PC-3 and (D) ES-2 cells. ‘a’, cells that did not receive any lidocaine treatment, and were exposed to Ca2+-free Tyrode's solution after uploaded the Fluo-3 AM fluorescence kit. The fluorescence curve of those cells is used as baseline for [Ca2+]I; ‘b’, the cells were treated with lidocaine (100 µM) for 12 h, and exposed to Tyrode's solution (with CaCl2) after using the Fluo-3 AM fluorescence kit; ‘c’, the cells did not receive any lidocaine treatment, but were exposed to Tyrode's solution (with CaCl2) after using the Fluo-3 AM fluorescence kit; dotted line, the cells did not receive any lidocaine treatment and after using the Fluo-3 AM fluorescence kit, the fluorescence curve of those cells was used as a negative control. Following exposure to Tyrode's solution (with CaCl2), the fluorescence curve of [Ca2+]I of the cells that received the lidocaine treatment was higher than baseline, but lower than the cells that did not receive the lidocaine treatment. This indicated that lidocaine (100 µM) treatment led to a significant decrease in the [Ca2+]I of the MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells.

Lidocaine inhibits cell migration

The inhibitory effect of lidocaine on TRPV6-expressing cancer cells was assessed by measuring the migration distance of the wound area using the wound healing assay. As shown in Fig. 2, the migration distance of the MDA-MB-231 cells treated with different concentrations of lidocaine (0 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM and 1 mM) was 574.3±17.5, 525.3±13.3, 477.1±20.5 and 264.0±10.2 µm, respectively. In the PC3 cells, following treatment with these different concentrations of lidocaine, the migration distance was 427.9±13.1, 410.3±10.1, 388.3±28.8 and 247.3±21.5 µm, respectively. Moreover, the migration distance of the ES-2 cells treated with these different concentrations of lidocaine was 593.8±6.5, 572.6±2.9, 420.1±25.1 and 264.3±14.2 µm, respectively. Compared with the control group, the 10-µM treatment group showed no significant inhibition of cell migration at the 24-h time point (MDA-MB-231, P=0.059; PC3, P=0.305; ES-2, P=0.119), but 100 µM (MDA-MB-231, P<0.01; PC3, P=0.039; ES-2, P<0.01) and 1 mM lidocaine demonstrated a significant inhibitory effect (P<0.01).

Figure 2.

Effect of lidocaine on the cell migration of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 6-expressing cancer cells. The cells were wounded with a sterile 10-µl plastic micropipette tip to generate a clean scratch wound across the center of the well, and then exposed to different concentrations (0 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM and 1 mM) of lidocaine for 24 h. (A) The migration distance of the cells was evaluated by the wound healing assay at the 0- and 24-h time points (×200 magnification). The histograms represent the migration distance of the (B) MDA-MB-231, (C) PC-3 and (D) ES-2 cells at different concentrations of lidocaine, and the data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control group.

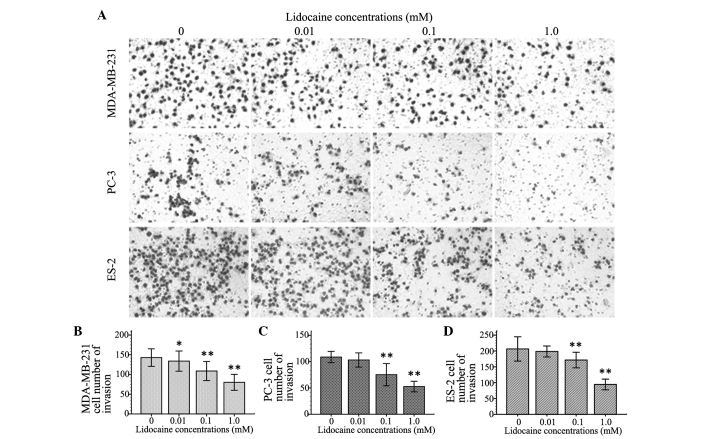

Lidocaine inhibits cell invasion

To observe the inhibitory effect of lidocaine on the invasion of TRPV6-expressing cancer cells, the number of invasive cells was counted using the cell invasion assay. Cell invasion following treatment with different concentrations of lidocaine (10 µM, 100 µM and 1 mM) decreased by different degrees in the three cell lines compared with control group. The inhibitory effect on cell invasion was enhanced with increasing concentrations of lidocaine. As shown in Fig. 3, At 100 µM and 1 mM, lidocaine remarkably inhibited cell migration of the MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells (P<0.01). Additionally, 10 µM lidocaine caused a significant inhibitory effect on migration in the MDA-MB-231 cells (P=0.039), but not in the PC-3 (P=0.111) and ES-2 cells (P=0.092).

Figure 3.

Effect of lidocaine on the invasion of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 6-expressing cancer cells. The cells were exposed to different concentrations (0 µm, 10 µm, 100 µm and 1 mM) of lidocaine for 24 h. (A) The invasion of cells was evaluated by the Transwell chamber invasion assay and the number of invasding cells was counted after staining with azure eosin methylene blue (×200 magnification). The histograms represent the number of (B) MDA-MB-231, (C) PC-3 and (D) ES-2 cells that penetrated the polycarbonate filter membrane with regard to different concentrations of lidocaine, and the data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control group.

Lidocaine reduces the rate of [Ca2+]I

The inhibitory effect of lidocaine on the function of the calcium channel TRPV6 basal calcium influx in TRPV6-expressing cancer cells was investigated using a Fluo-3 AM fluorescence kit. After Fluo-3 AM staining, flow cytometry investigation revealed that the spectral shift of the fluorescence curve of treated cells following exposure to Tyrode's solution (with 1.5 mM CaCl2) was lower than that of the control group. This indicated that lidocaine (100 µM) treatment led to a significant decrease in the [Ca2+]I of the MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 1B), PC-3 (Fig. 1C) and ES-2 (Fig. 1D) cells.

Lidocaine downregulates TRPV6 expression

The present study found that a 100-µM lidocaine treatment could significantly inhibit cell invasion and cell migration, and decrease intracellular-free Ca2+ in TRPV6-expressing cells. Therefore, the expression of TRPV6 mRNA and protein in the cells treated with lidocaine was investigated to determine whether lidocaine inhibited TRPV6-expressing cancer cell invasion and migration through TRPV6 downregulation. As shown in Fig. 4A, compared with control group, the expression of TRPV6 mRNA in the MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells treated with 100 µM lidocaine for 12 h was decreased by 81.54±5.47% (P<0.01), 56.63±5.65% (P=0.002) and 78.82±5.75% (P<0.01), respectively. The protein expression of TRPV6 in the treated cells was lower than that in the control group (MDA-MB-231, P<0.01; PC3, P=0.001; ES-2, P=0.012) (Fig. 4B and C). The quantitative PCR and western blot analyses revealed that 100 µM lidocaine downregulated TRPV6 at the mRNA and protein levels.

Figure 4.

Effect of lidocaine on the expression of TRPV6 in MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells. The cells were exposed to lidocaine (100 µM) for 12 h, then the expression of (A) TRPV6 mRNA was evaluated by quantitative PCR analysis, and the expression of (B and C) TRPV6 protein was investigated by western blot analysis. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control group. TRPV6, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 6.

Discussion

Retrospective studies have suggested that regional anesthesia plays a beneficial role in the prevention of cancer metastasis and recurrence, and that this may be attributed to the inhibition of the surgical stress response and a decrease in opioid analgesia requirement after cancer surgery. Local anesthetics are not only used for nerve blocks, pain control, and anti-arrhythmia and anti-inflammatory purposes, but can also cause neuronal cell death and the death of other cell types (18–20). It has even been speculated that the cytotoxicity of local anesthetics could play an important antitumor role. Chang et al (16) found that lidocaine and bupivacaine may be ideal infiltration anesthetics for breast cancer surgery as they could induce apoptosis of human breast cancer cells at clinically relevant concentrations, and since they demonstrated potential benefits of local anesthetics. Subsequently, after investigating lidocaine and bupivacaine treatment in human thyroid cancer cells, the study also found a significant decrease in cell viability and colony formation in a dose-dependent manner as the result of treatment with lidocaine and bupivacaine at higher concentrations, and suggested that lidocaine and bupivacaine may induce cell apoptosis through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (21). The present study assessed the cytotoxicity of lidocaine at 1 to 10 mM and also found that lidocaine was able to significantly decreased cell viability of MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. Moreover, lidocaine inhibited the migration and invasion of the cancer cells at concentrations that are much lower than clinical concentrations. The migration distance and the number of invading cells following treatment with 100 µM lidocaine was markedly decreased.

Local anesthetics can block Ca2+ channels, as well as voltage-dependent sodium and K+ channels during regional anesthesia (17). Ca2+, as an extracellular and intracellular signaling ion, is essential for the growth, proliferation and survival of normal and malignant cells. The increase in [Ca2+]I that is involved in cell migration has been known about for a long time (22). In the present study, the [Ca2+]I was measured using a Fluo-3 AM fluorescence kit and the fluorescence spectra was analyzed using flow cytometry. It was found that the calcium homeostasis of the MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells had been altered following exposure to Tyrode's solution (with CaC12). The fluorescence spectra of [Ca2+]I was lower than that of the control cells, indicating that lidocaine (100 µM) treatment led to a significant decrease in the [Ca2+]I of the MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells, and was accompanied by a concomitant inhibition of the migration and invasion of the treated cells.

Recent findings have shown that TRP and SOC channels, ORAI1 and stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), are involved in cancer cell metastasis (3). A study by Yang et al (2) demonstrated that ORAI1 and STIM1 were essential for breast cancer cell migration in vitro and metastasis in mice, and suggested that SOC channels have the potential as a therapeutic target in breast cancer. TRP channels, as well as SOC channels, have become a focus of attention due to their potential role as diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic targets in human tumors. Compared with other TRP channels, TRPV6 channels participate in the regulation of calcium homeostasis in the body and have high calcium selectivity. TRPV6 channels have a direct affect upon intestinal calcium absorption, renal calcium excretion and bone metabolism (3,11). TRPV6 also appears to play a role as encoded by a possible oncogene in tumor development and progression, as it was observed to be upregulated and correlated with tumor grade in prostate, breast, ovarian, thyroid, colon and pancreatic tumors (8,9,23). The exact role of TRPV6 in tumor development and progression for the majority of cancer types is not clear, but it has been demonstrated that calcium signaling controls cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis via the TRPV6 channel. Schwarz et al (24) suggested that TRPV6 increases the rate of prostate cancer HEK-293 cell proliferation in a Ca2+-dependent manner and correlates with slightly increased [Ca2+]I. Lehen'kyi et al (25) found that TRPV6 silencing in prostate cancer LNCaP cells decreased the cell proliferation rate and the percentage of cells in the S-phase of the cell cycle. Peters et al (6) also found a reduced percentage of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cells in the S-phase after TRPV6 small interfering RNA treatment. Furthermore, it was found that the cells accumulated in the G1-phase, and this was attributed to the attenuation of the calcium influx associated with TRPV6 inhibition. In the present study, lidocaine was shown to downregulate TRPV6 expression. Compared with that of the control group, the expression of TRPV6 mRNA and protein in the TRPV6-expressing cells with lidocaine treatment was decreased significantly. The inhibition of cell invasion and migration resulted in the attenuation of calcium influx associated with lidocaine, impacting TRPV6 expression in the MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells. There are other potential calcium permeable channels, e.g., TRPC4 and TRPC6, which could also be contributing to the calcium uptake in the cancer cells (26). Therefore, their positive contribution to this study could not be ruled out; however, the present results indicate that TRPV6 has a major impact on cellular calcium entry.

In summary, lidocaine inhibits the cell invasion and migration of MDA-MB-231, PC-3 and ES-2 cells at lower than clinical concentrations. The inhibitory effect of lidocaine on TRPV6-expressing cancer cells was associated with a reduced rate of calcium influx, and could occur partly as a result of the downregulation of TRPV6 expression. The use of appropriate local anesthetics may confer potential benefits in clinical practice for the treatment of patients with TRPV6-expressing cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81171859) and by a Chongqing Municipal Healthcare Department Medical Research Grant (no. 2010-1-20:2). The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to Dr Yi Yuan (The Affiliated Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China), Dr Wenfang Li (Shiyan Taihe Hospital, Shiyan, China), Dr Jianguo Hu (The Second Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University, Chonqing, China), Mr. Meicai Li (Chongqing Three Gorges Central Hospital, Chonqing, China) and Miss Zunzhen Zhou (Chongqing Medwise Anorectal Hospital, Chonqing, China) for providing useful assistance.

References

- 1.Mao L, Lin S, Lin J. The effects of anesthetics on tumor progression. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2013;5:1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang S, Zhang JJ, Huang XY. Orai1 and STIM1 are critical for breast tumor cell migration and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Calcium in tumour metastasis: New roles for known actors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:609–618. doi: 10.1038/nrc3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J, Ishihara A, Oxford G, Johnson B, Jacobson K. Regulation of cell movement is mediated by stretch-activated calcium channels. Nature. 1999;400:382–386. doi: 10.1038/22578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang S, Huang XY. Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels controls the trailing tail contraction in growth factor-induced fibroblast cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27130–27137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters AA, Simpson PT, Bassett JJ, Lee JM, Da Silva L, Reid LE, Song S, Parat MO, Lakhani SR, Kenny PA, et al. Calcium channel TRPV6 as a potential therapeutic target in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2158–2168. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen CV, DeBay D, Ewart HS, Gallant P, Gormley S, Ilenchuk TT, Iqbal U, Lutes T, Martina M, Mealing G. In Vivo detection of human TRPV6-Rich tumors with anti-cancer peptides derived from soricidin. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhenin-Duthille I, Gautier M, Faouzi M, Guilbert A, Brevet M, Vaudry D, Ahidouch A, Sevestre H, Ouadid-Ahidouch H. High expression of transient receptor potential channels in human breast cancer epithelial cells and tissues: Correlation with pathological parameters. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28:813–822. doi: 10.1159/000335795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng JB, Zhuang L, Berger UV, Adam RM, Williams BJ, Brown EM, Hediger MA, Freeman MR. CaT1 expression correlates with tumor grade in prostate cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:729–734. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolanz KA, Kovacs GG, Landowski CP, Hediger MA. Tamoxifen inhibits TRPV6 activity via estrogen receptor-independent pathways in TRPV6-expressing MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:2000–2010. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gkika D, Prevarskaya N. TRP channels in prostate cancer: The good, the bad and the ugly? Asian J Androl. 2011;13:673–676. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exadaktylos AK, Buggy DJ, Moriarty DC, Mascha E, Sessler DI. Can anesthetic technique for primary breast cancer surgery affect recurrence or metastasis? Anesthesiology. 2006;105:660–664. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottschalk A, Ford JG, Regelin CC, You J, Mascha EJ, Sessler DI, Durieux ME, Nemergut EC. Association between epidural analgesia and cancer recurrence after colorectal cancer surgery. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:27–34. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181de6d0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yildirim S, Altun S, Gumushan H, Patel A, Djamgoz MB. Voltage-gated sodium channel activity promotes prostate cancer metastasis in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2012;323:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brackenbury WJ. Voltage-gated sodium channels and metastatic disease. Channels (Austin) 2012;6:352–361. doi: 10.4161/chan.21910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang YC, Liu CL, Chen MJ, Hsu YW, Chen SN, Lin CH, Chen CM, Yang FM, Hu MC. Local anesthetics induce apoptosis in human breast tumor cells. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:116–124. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a94479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Castro R, Patel S, Garavito-Aguilar ZV, Rosenberg A, Recio-Pinto E, Zhang J, Blanck TJ, Xu F. Cytotoxicity of local anesthetics in human neuronal cells. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:997–1007. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31819385e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou X, Li YH, Yu HZ, Wang RX, Fan TJ. Local anesthetic lidocaine induces apoptosis in human corneal stromal cells in vitro. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6:766–771. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.06.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breu A, Ecki S, Zink W, Kujat R, Angele P. Cytotoxicity of local anesthetics on human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1676–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HT, Xu H, Siegel CD, Krichevsky IE. Local anesthetics induce human renal cell apoptosis. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23:129–139. doi: 10.1159/000069304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang YC, Hsu YC, Liu CL, Huang SY, Hu MC, Cheng SP. Local anesthetics induce apoptosis in human thyroid cancer cells through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolanz KA, Hediger MA, Landowski CP. The role of TRPV6 in breast carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:271–279. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raphaël M, Lehen'kyi V1, Vandenberghe M, Beck B, Khalimonchyk S, Vanden Abeele F, Farsetti L, Germain E, Bokhobza A, Mihalache A. TRPV6 calcium channel translocates to the plasma membrane via Orai1-mediated mechanism and controls cancer cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E3870–E3879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413409111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarz EC, Wissenbacn U, Niemeyer BA, Strauss B, Philipp SE, Flockerzi V, Hoth M. TRPV6 potentiates calcium-dependent cell proliferation. Cell Calcium. 2006;39:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehen'kyi V, Raphaël M, Prevarskaya N. The role of the TRPV6 channel in cancer. J Physiol. 2012;590:1369–1376. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bödding M. TRP proteins and cancer. Cell Signal. 2007;19:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]