Abstract

Objective

Intimacy is an essential part of marital relationships, spiritual relationships, and is also a factor in well-being, but there is little research simultaneously examining the links among spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being.

Methods

Structural equation modeling was used to examine associations among the latent variables—spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, spiritual meaning, and well-being—in a cross-sectional study of 5,720 married adults aged 29–100 years (M = 58.88, SD = 12.76, 59% female). All participants were from the Adventist Health Study-2, Biopsychosocial Religion and Health Study.

Results

In the original structural model, all direct associations between the three latent variables of spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being were significantly positive indicating that there was a significant relationship among spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being. When spiritual meaning was added as a mediating variable, the direct connections of spiritual intimacy to marital intimacy and to well-being became weakly negative. However, the indirect associations of spiritual intimacy with marital intimacy and with well-being were then strongly positive through spiritual meaning. This indicates that the relationship among spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being was primarily a result of the meaning that spiritual intimacy brought to one’s marriage and well-being, and that without spiritual meaning greater spirituality could negatively influence one’s marriage and well-being.

Conclusions

These findings suggest the central place of spiritual meaning in understanding the relationship of spiritual intimacy to marital intimacy and to well-being.

Keywords: intimacy, spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, well-being, marriage, meaning in life

Intimacy may be defined as a relational process involving reciprocal sharing with and coming to know about the private, innermost aspects of another person (Chelune, Robison, & Kommor, 1984). Intimacy is an essential factor in the interpersonal relationships of everyday life, a core component of the perceived spiritual relationship with God in Biblical Christianity (Simpson, Newman, & Fuqua, 2008), and is an integral part of well-being, as both spiritual and interpersonal relationships contribute to well-being (Charlemagne-Badal, Lee, Butler, & Fraser, 2014; Sneed, Whitbourne, Schwartz, & Huang, 2011).

Much of the research on relational/marital intimacy has focused on communication (Gable, Gonzaga, & Strachman, 2006) and interpersonal dynamics within couples (Mirgain & Cordova, 2007). Others have examined a perceived relationship to God (spiritual intimacy) and have focused on how this perceived intimacy is influenced by how one views God (Davis, Moriarty, & Mauch, 2013). The perception of a personal relationship with God can give purpose to life and changes priorities in one’s life (Dollahite & Marks, 2009; Emmons, 2005). Such purpose, in turn, affects intimate relationships (Pollard, Riggs, & Hook, 2014). This is consistent with the theoretical concept of spiritual modeling (Silberman, 2003) which draws on Bandura’s (2003) social learning theory to suggest life meaning, marital intimacy, and well-being are enhanced when one perceives that a personal relationship with God is being manifested in one’s life.

Researchers have examined how one’s intimate relationships (Ditzen, Hoppman, & Klumb, 2008) and spirituality (Morton, Lee, Haviland, & Fraser, 2012) affect well-being but no studies to date have simultaneously examined the links among spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, spiritual meaning, and well-being, although common elements suggest how they may be related.

Definitions

For this study, intimacy is defined as “feeling understood, validated, cared for, and closely connected with another person [or with God]” (Reis & Shaver, 1988, p. 385). Specifically, this study examines respondents’ intimacy in their relationships with their spouses (marital intimacy) and in their perceived relationships to God (spiritual intimacy). Well-being is defined as “a state of optimal regulation and adaptive functioning of body, mind, and relationships” (Siegel, 2012, p. 459). For this study the measurement of well-being is focused on measuring respondents’ physical well-being (e.g., difficulty in doing work or activities because of physical health), psychological well-being (e.g., unable to get work done because of emotional problems), and life satisfaction, given that the other constructs are focused on relational well-being (e.g., marital intimacy, spiritual intimacy). Mascaro, Rosen, and Morey (2004, p. 845) define spiritual meaning as “the extent to which an individual believes that life or some force of which life is a function has a purpose, will, or way in which individuals participate.”

Marital Intimacy

Intimacy within relationships is multi-faceted and depends on several factors. Strongly associated with the level of intimacy is one’s perception of the intimate relationship and the nuances of communication between relationship partners.

Perceptual factors of intimacy

Feeling safe when expressing vulnerability (Cordova & Scott, 2001) and during times of conflict (Dorian & Cordova, 2004) are important components of intimacy. Partner responsiveness is important to feeling safe (Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998) and is related to greater openness and emotional risk-taking especially when outcomes are unpredictable or potentially undesirable (Carter & Carter, 2010).

Commitment and faithfulness are also key factors for feeling safe in a relationship. Commitment and its resulting feelings of safety are the most powerful and consistent predictors of marital satisfaction (Acker & Davis, 1992). The strength of commitment to a romantic relationship is also associated with feelings of satisfaction (Impett, Beals, & Peplau, 2002).

Communication

Communication is a vital factor in determining the tenor and perceived closeness of intimate relationships. Confiding in one’s spouse is positively associated with intimacy and relationship satisfaction (Lee, 1988). Communicating personal positive events increases relationship well-being, perceived intimacy (Gable et al., 2006), and a sense of trust (Gable, Reis, Impett, & Asher, 2004).

Spiritual Intimacy

For the Christian, the idea of intimate oneness is a key aspect of spirituality because it characterizes the perceived relationship to God as stated in Acts 17:28, “In Him we live, and move, and have our being” (New International Version). Yet, the concept of spiritual intimacy remains somewhat ambiguous. Several broad themes emerge from the extant literature: how one views God, the prayer/communication relationship with God, and the purpose and priority of having a perceived intimate relationship with God that adds meaning to life.

Perceptual views and experiences of God

Vital to one’s understanding of spirituality is one’s view of God, whether from what Davis et al. (2013) refer to as “heart knowledge”—images of the divine involving “embodied emotional experience” (p. 52)—or from what they refer to as “head knowledge” that involve concepts of the divine—theological beliefs. The distinction involves experiential versus cognitive representations of God—affect laden versus affect light. One’s internal images of God provide the basis for one’s attachment to God and in turn influence how one integrates this perceived relationship with God into one’s life.

Communication through prayer

As with marital intimacy, communication is key to spiritual intimacy. Prayer is one important method of communicating with God. The best predictor of perceived intimacy with God for young people is the use of prayers of praise, whereas for older people it is prayers of thanksgiving that become more selfless and frequent as people age (Hayward & Kraus, 2013).

Spiritual Meaning

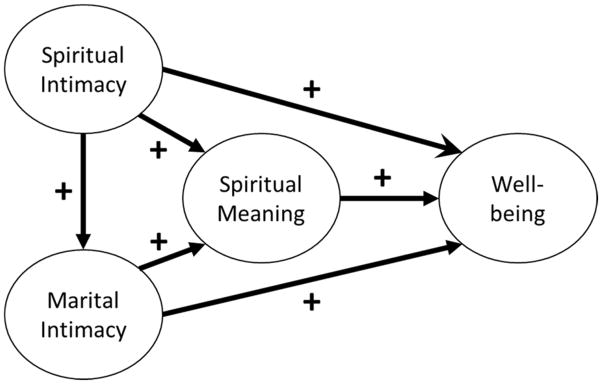

Spiritual meaning may be conceptualized as one aspect of perceived intimacy with God or as a distinct construct, reflecting a process in which cognitive and emotional factors combine to create a sense of cohesion or meaning that is linked to their spiritual beliefs as seen in Mascaro’s (2004) definition. We initially took the first approach, defining spiritual meaning as one facet of spiritual intimacy and did not include spiritual meaning as a potential mediator. Reflection on the model, however, led us to believe that spiritual meaning was more central to the processes we were exploring, and not merely a subcomponent of spiritual intimacy. This second approach, and our initial expectations regarding relationships among the variables, are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Simple meditational model. Our conceptual model posits that, for spiritually oriented married couples, spiritual meaning (i.e., “the extent to which an individual believes that life or some force of which life is a function has a purpose, will, or way in which individuals participate,” Mascaro et al., 2004, p. 845) is the mechanism through which both marital and spiritual intimacy are related to physical/psychological well-being. That is, variation in both marital and spiritual intimacy predict variation in spiritual meaning, which in turn predict variation in physical/psychological well-being. We argue this indirect effect occurs because spiritually oriented married couples cultivate marital and spiritual intimacy partly to nurture their sense of spiritual meaning, which in turn enhances their physical/psychological well-being.

Spiritual meaning seems to be importantly related to well-being. The presence of spiritual content in purposes and goals has a strong impact on well-being (Emmons, Cheung, & Tehrani, 1998) and a perceived relationship to God promotes purpose and direction (McCullough & Willoughby, 2009) and enhances a sense of life’s meaning through goals and values systems (Emmons, 2005) and the prioritization of faith and family over self (Dollahite & Marks, 2009).

Well-Being

Well-being is a broad concept with varying definitions and measurement tools. In this study we focus on the constructs of life satisfaction and perceived psychological and physical health.

Parallels and Associations of Relational and Spiritual Intimacy

Many of the characteristics that are hallmarks of marital intimacy—commitment, purpose, communication, loyalty, faithfulness, safety, caring, mindfulness/empathy (Wachs & Cordova, 2007), and selflessness—have parallel characteristics in perceived spiritual intimacy. These include commitment to God, a God-centered life purpose, communication through prayer, and feeling safe and cared for by God. Because these values lay the foundation for purposeful living and intentional intimacy with God, we propose that this perceived intimacy with God will through spiritual modeling, positively affect marital intimacy and individual well-being.

The perception of spiritual intimacy has been positively linked to marital satisfaction through a path of emotional intimacy (Greeff & Malherbe, 2001; Hatch, James, & Schumm, 1986). Additionally there is a strong positive correlation between intrinsic religiosity and marital satisfaction with the strongest factors being shared religious activities and congruence of individual beliefs with how one lives one’s life (Dudley & Kosinski, 1990). Congruence in faith practices is also important in fostering marital intimacy (Vaaler, Ellison, & Powers, 2009), as is praying for one’s spouse (Fincham, Beach, Lambert, Stillman, & Braithwaite, 2008).

Study Objectives

There is limited research that simultaneously addresses how spiritual intimacy and marital intimacy are related to well-being, and how spiritual meaning might relate to all three. In addition, research in this area has focused primarily on young adults, leaving unanswered questions about how these factors might look for older adults in long-term committed relationships.

Extant literature suggests that people turn to the Christian religion because of the perceived personal nature of God in their lives (Moriarty & Davis, 2012). Studying spiritual intimacy among Christians is particularly fruitful because the Christian religion has a unifying effect among the beliefs of its adherents. This effect is more pronounced in conservative religious denominations, such as Seventh-day Adventists; thus this study will focus on this distinct group.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data for this study were drawn from the Biopsychosocial Religion and Health Study (BRHS; Lee et al., 2009), a subset of the Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2; Butler et al., 2008). The aim of the BRHS was to examine a cohort of Seventh-day Adventists and determine how religious experience affects cumulative risk exposure involving quality of life and health, as well as to look at how religious mechanisms might operate in influencing health. Data for this study were collected from the first wave of the BRHS in 2006–2007.

The 20-page BRHS questionnaire was sent to a random sample of approximately 21,000 individuals (10,988 responses), ages 35 and above participating in the AHS-2. The questionnaires included items pertaining to physical and socioeconomic stress; affective, cognitive, behavioral, and social aspects of religion; lifestyle and other factors such as health behaviors, social interactions, emotions, coping strategies, and self-efficacy; and areas of well-being such as quality of life, life satisfaction, and medical histories. All data collection procedures were approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board.

Only currently-married participants were included (N = 7,270) in this study. Participants missing any of the study variables were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of 5,720 or 78.7% of the currently-married subsample (M age = 58.88 years, SD = 12.76). Table 1 shows the sample demographics in more detail. The sample with no missing data was significantly younger (58.9 years vs. 63.8), less female (59% vs. 65%), more White (67% vs. 59%), and had slightly higher education (bachelor’s degree: 26% vs. 20%) compared to those who were excluded.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Female

|

Male

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | N | |

| Age Range (years) | ||||

| 44 and below | 16.6% | 562a | 11.4% | 267b |

| 45–54 | 26.9% | 909a | 21.3% | 499b |

| 55–64 | 27.6% | 934a | 27.1% | 634a |

| 65–75 | 18.8% | 637a | 22.8% | 532b |

| 75–84 | 9.1% | 309a | 14.2% | 331b |

| 85 and above | 0.9% | 31a | 3.2% | 75b |

| Length of Relationship | ||||

| married 10 years or less | 13.8% | 467a | 14.2% | 332a |

| married 11–20 years | 20.8% | 704a | 19.7% | 461a |

| married 21–30 years | 22.3% | 753a | 18.6% | 435a |

| married 31–40 years | 19.9% | 672a | 19.3% | 452a |

| married 41–50 years | 12.4% | 420a | 15.0% | 350b |

| married >50 years | 10.8% | 366a | 13.2% | 308b |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 65.3% | 2208a | 68.9% | 1610b |

| Black | 28.0% | 948a | 25.4% | 594b |

| Other | 6.7% | 226a | 5.7% | 134b |

| Highest education | ||||

| Grade School | 0.7% | 22a | 1.5% | 34b |

| Some High School | 2.7% | 59a | 2.6% | 60a |

| High School diploma | 11.6% | 393a | 8.6% | 201b |

| Trade school diploma | 4.6% | 156a | 4.1% | 97a |

| Some college | 21.6% | 729a | 16.9% | 395b |

| Associate degree | 14.7% | 496a | 8.3% | 193b |

| Bachelors degree | 27.0% | 912a | 23.6% | 551b |

| Masters degree | 14.1% | 476a | 18.9% | 442b |

| Doctoral degree | 3.2% | 108a | 15.6% | 365b |

| Total n | 3382 | 2338 | ||

Note: Values in the same row not sharing the same subscript are significantly different at p < .05 in the two-sided test of equality for column proportions. Tests assume equal variances.

Measures

Control variables

Age and length of relationship were selected as control variables since both appear to be strongly related to spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being in our preliminary correlation analyses and in the literature. This relationship is also seen in the current research literature (Ahmetoglu, Swami, & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2010; Baesler, 2002; Stroope, McFarland, & Ueker, 2014).

Latent constructs

Three initial primary latent constructs were formed: spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being and a model tested relating these three. It was then hypothesized that the secondary construct of spiritual meaning might play a more direct role as shown in Figure 1, thus it was added as a primary latent variable to the second model. Cronbach’s α reported below on scales used as manifest variables were calculated from the final sample.ahead

Spiritual intimacy

Spiritual intimacy was conceived as a composite of two latent constructs: perceived relationship to God and positive religious coping. These two constructs encompass both one’s private relationship with God and one’s relationship with God lived out in how one chooses to respond to day-to-day stressors.

Perceived relationship to God

Perceived relationship to God consisted of four manifest variables: intrinsic religiosity, Bible study, communication with God, and contemplation of God. Intrinsic religiosity was measured using the 3-item intrinsic religiosity scale of the DUREL (Koenig et al., 1997; e.g., “I try hard to carry my religion over into all my other dealings in life”). Responses ranged from not true (1) to very true (7). Cronbach’s α was .74. Bible study was measured using a single item derived from the DUREL (Koenig et al., 1997; “How often do you spend time in private Bible study?”) with responses including never (1) to more than once a day (8). No Cronbach’s α was available since this was a single item. Communication with God was measured using a composite created from seven items from the Luckow et al.’s (1999) confession and habit prayer scales which included items such as “When I pray I want to share my life with God.” Responses ranged from definitely false (1) to definitely true (7). Cronbach’s α was .82. Our factor analytic examination of these seven items suggested a single factor in our sample. Contemplation of God was measured using the five items of the Paloma and Pendleton (1991) contemplative prayer scale (e.g., “Spend time just feeling or being in the presence of God”). Responses ranged from never (1) to very often (5). Cronbach’s α was .83.

Positive religious coping

Positive religious coping was measured using four scales from the RCOPE: spiritual support, benevolent reappraisal, collaboration with God, and active surrender (Pargament, 1999). All four scales involved answers to the overall question, “In dealing with major problems, to what extent have each of the following been involved in the way you cope?” Responses ranged from not at all (1) to a great deal (5). Each scale was composed of three items for a total of 12 items with the following items as examples: spiritual support “Worked together with God as partners” (Cronbach’s α = .90), benevolent appraisal “Saw my situation as part of God’s plan” (Cronbach’s α = .84), collaborative “Worked together with God as partners” (Cronbach’s α = .84), and active surrender “Did my best and then turned the situation over to God” (Cronbach’s α = .88).

Marital intimacy

Marital intimacy was measured using two scales (Ryff, Singer, & Palmersheim, 2004) with six items for positive (Cronbach’s α = .90) and five items for negative intimacy (Cronbach’s α = .83). Example items are (positive) “How much does/did your spouse or partner really care about you?” and (negative) “How often does/did your spouse or partner make you feel tense?” Responses ranged from not at all (1) to a lot (4).

Spiritual meaning

Spiritual meaning in life was measured using the 5-item spiritual meaning scale (Mascaro, Rosen, & Morey, 2004). An example item is “I see a special purpose for myself in this world” with responses ranging from not true (1) to very true (7). Cronbach’s α was .73.

Well-being

The latent construct of well-being was assessed using measures of physical health, psychological health, and life satisfaction. In the structural equation model these three were used to indicate one latent variable measuring overall well-being. These three are described in more detail below.

Physical health and psychological health were measured, respectively, using the SF-12 composite physical health and composite mental health scales (Ware, Kosinski, Turner-Bowker, & Gandex, 2002). These are weighted sums of the eight SF-12 items with different weights for psychological and physical health which allowed no Cronbach’s α. Examples are “During the past 4 weeks how much of the time have you had any of the following problems with work or other regular daily activities as a result of any emotional problems: Accomplished less than you would like? Did work or activities less carefully than usual?” Response ranges differed for the various subscales. The scoring weights were based on two separate factors repeatedly found in factor analysis of the SF-12 items (Ware et al., 2002).

Life satisfaction was measured using the 5-item life satisfaction scale (Diener et al., 1985) An example is, “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” with responses ranging from not true (1) to very true (7). Cronbach’s α was .87.

Analyses

To test the relationships between spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being, structural equation modeling (SEM, Amos 22; Arbuckle, 2013) was used, as well as SPSS 22 to run descriptive statistics and to manage data. The causal model consisted of 18 manifest variables reflecting the overarching constructs in Figure 1 of spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, spiritual meaning, and well-being with age and length of relationship as control variables. Modification indices were examined to check for correlations between the error variances of these variables. Three separate models were run: one including spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being; a second, adding spiritual meaning as a mediating variable; and a third as a comparison model with the full model with the spiritual meaning paths constrained to zero. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was used to evaluate the fit of the models with a target of < .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999); the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) with a target of < .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999); and the normed fit index (NFI) with acceptable model fit indicated by a value > .90 (Byrne, 1994). A 1,000 sample-adjusted bootstrap with 95% confidence intervals was used for both models. Confidence intervals were compared to check for potential interactions in the groups, looking for significant differences as evidenced by non-overlapping confidence intervals (Cummings & Finch, 2005). The criterion for statistical significance was p < .05.

Results

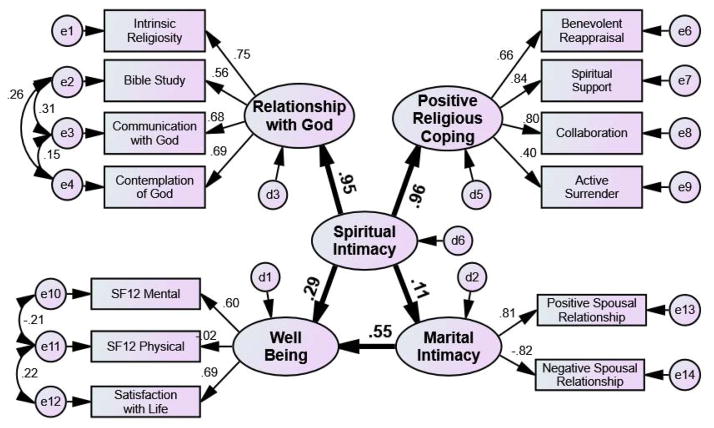

Structural Model for the Relationships Among Spiritual Intimacy, Marital Intimacy, and Well-Being

The basic model is shown in Figure 2. All pathways were positive. The weakest path was between spiritual intimacy and marital intimacy (.11, p = .003). All other path coefficients were .29 or greater and were statistically significant at p ≤ .002. All indices indicated good model fit (RMSEA .05 [CI: .05, .06], SRMR .04, NFI .96). These findings suggest that spiritual intimacy is an important contributor to both marital intimacy and well-being in that one’s relationship with God has a significantly positive effect on one’s marital intimacy and well-being.

Figure 2.

Original causal model (n = 5,720). This model demonstrates that there are significant associations among spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being in that one’s relationship with God can directly improve one’s marital intimacy and well-being. Spiritual intimacy is also potentiated by improving marital intimacy which in turn improves well-being. Standardized regression coefficients from structural model are shown. Age and length of relationship are controlled. Structural model of relationship between latent variables is shown with bold-faced arrows and coefficients. All coefficients are statistically significant at p < .001 (except for well-being to SF-12 physical which is not significant) using bias-corrected 1,000 sample bootstrap. x2 (73) = 1288.60, p = .000, RMSEA = .05 (95% CI = .05, .06), SRMR = .04, NFI .96. Numbers beside latent and manifest variables are squared multiple correlations for all arrows leading into that variable. Numbers on arrows are standardized path coefficients.

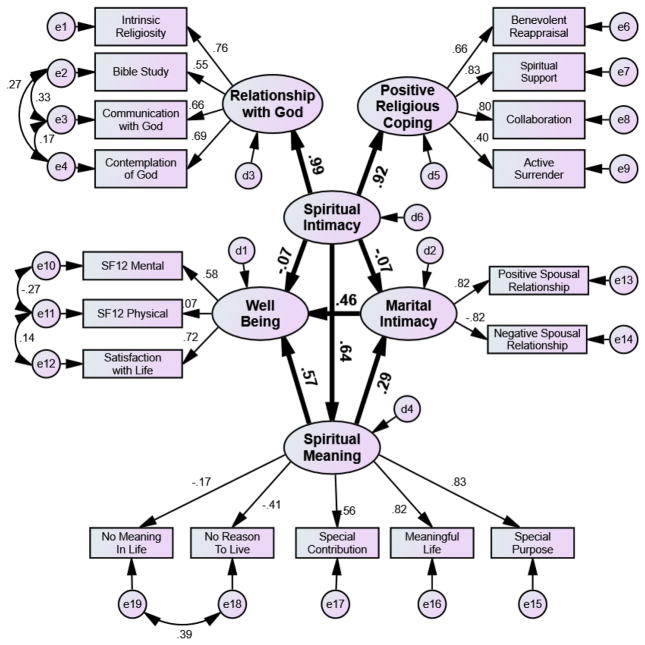

Effects of Adding Spiritual Meaning Into the Model

Figure 3 shows the final structural equation model with spiritual meaning included as a mediating variable. While all links are statistically significant at p ≤ .01 and all fit indices are acceptable (RMSEA .049 [CI: .047, .050], SRMR .04, NFI .95), not all pathways are positive. The direct connections from spiritual intimacy to well-being and to marital intimacy became negative when spiritual meaning was added as a mediator, demonstrating strong indirect associations of spiritual intimacy with marital intimacy and well-being, acting through spiritual meaning. To determine whether adding spiritual meaning in this central position was an improvement over a model without connections through spiritual meaning we tested the model shown in Figure 3 with the paths from spiritual meaning to marital intimacy and to well-being constrained to zero. The results of this model (not shown) were very similar to the model without spiritual meaning we initially tested in Figure 2. The direct paths from spiritual intimacy to marital intimacy (0.14, 95% CI [0.11, 0.18], p = .002) and from spiritual intimacy to well-being (0.35, 95% CI [0.31, 0.38], p = .002) were both reasonably strong and positive. Additionally, the model not containing the constraints is a better fit to the data than the constrained model (χ2 (2) = 797.18, p < .005). These findings suggest that spiritual meaning is the vehicle through which spiritual intimacy is modeled to facilitate greater marital intimacy and well-being. In other words, it is the spiritual meaning that is a result of one’s relationship with God that is the impetus and model for greater levels of intimacy in one’s marriage and increased individual well-being.

Figure 3.

Final causal model (n = 5,720). Spiritual intimacy is the best predictor of one’s marital intimacy and well-being through the lens of spiritual meaning. When one’s relationship with God creates meaning and purpose in one’s life, it positively improves both marital intimacy and well-being. The strongest positive change is seen for individual well-being in that spiritual intimacy, by improving marital intimacy, also improves well-being. Without spiritual meaning in one’s life, one’s relationship with God is associated with a decrease in marital intimacy and well-being. Standardized regression coefficients from structural model are shown. Age and length of relationship are controlled. Structural model of relationship between latent variables is shown with bold-faced arrows and coefficients. All coefficients are statistically significant at p < .005 using bias-corrected 1,000 sample bootstrap. x2 (147) = 2137.07, p < .001, RMSEA = .049 (95% CI = .047, .050), SRMR = .04, NFI .95. Numbers beside latent and manifest variables are squared multiple correlations for all arrows leading into that variable. Numbers on arrows are standardized path coefficients.

Connections Among Latent Variables

Direct, indirect, and total effects among all latent variables are shown in Table 2 along with their confidence limits and p values. All are statistically significant at p ≤ .01 or better.

Table 2.

Standardized Effects with Bias-Corrected Bootstrap 95% Confidence Intervals for All Paths in the Model Shown in Figure 2

| Final variable in the path | Initial variable in the path

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual Intimacy

|

Spiritual Meaning

|

Marital Intimacy

|

|||||||

| PC | 95% CI | p | PC | 95% CI | p | PC | 95% CI | p | |

| Standardized Direct Effects | |||||||||

| Spiritual Meaning (SM) | .64 | [.61, .67] | .002 | ||||||

| Marital Intimacy (MI) | −.07 | [−.12, −.03] | .001 | .29 | [.24, .35] | .002 | |||

| Well-Being (WB) | −.07 | [−.12, −.03] | .005 | .57 | [.52, .63] | .002 | .46 | [.42, .49] | .002 |

| Standardized Indirect Effects | |||||||||

| Marital Intimacy (MI) | .19a | [.15, .22] | .001 | ||||||

| Well-Being (WB) | .42b | [.38, .46] | .003 | .13c | [.11, .16] | .001 | |||

| Standardized Total Effects | |||||||||

| Spiritual Meaning (SM) | .64 | [.61, .67] | .002 | ||||||

| Marital Intimacy (MI) | .11 | [.08, .15] | .003 | .29 | [.24, .35] | .001 | |||

| Well-Being (WB) | .35 | [.30, .38] | .003 | .70 | [.66, .76] | .002 | .46 | [.42, .49] | .002 |

Note. PC = path coefficient; CI = confidence interval;

SI→SM→MI.

SI→SM→WB + SI→SM→MI→WB.

SM→MI→WB.

Direct effects

While all the direct paths among latent variables were significant, those pathways from spiritual intimacy to well-being and to marital intimacy were both relatively weak and negative. This shows the importance of spiritual meaning to marital intimacy and well-being and raises the specter of what is left that creates a negative relationship when spiritual intimacy is bereft of spiritual meaning.

Indirect effects

The indirect effects were mediated by spiritual meaning. The direct negative associations of spiritual intimacy with marital intimacy and with well-being were both strong and positive when considered as indirect effects working through spiritual meaning. This suggests the strong role of spiritual meaning when examining the relationship among spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being.

Total effects

As shown in Table 2, the total effects of spiritual intimacy to spiritual meaning, and of spiritual meaning to well-being were both strong relative to the other effects. The paths from spiritual and marital intimacy to well-being were somewhat weaker and the path from spiritual meaning to marital intimacy was the weakest though still significant. Spiritual meaning, thus, is strongest in relation to well-being, but also strong in relation to marital intimacy.

Potential Moderating Factors

Using the methods outlined in the analysis section, potential interactions were tested across the following groups: (a) gender, (b) length of marriage relationship by age group—both by tertiles and median split, (c) length of marriage relationship in 10-year increments using age as a control, and (d) ethnicity as well as ethnicity by gender using age as a control. There were no significant interactions suggesting that gender, length of relationship, and ethnicity do not change the strong mediational role of spiritual meaning in the association of marital and spiritual intimacy with well-being.

Discussion

The results of this study show that spiritual meaning, as a component of one’s relationship with God, is a strong predictor of increased marital intimacy and individual well-being. Having a relationship with God may improve one’s marital intimacy and well-being, but it is the spiritual meaning aspect of spiritual intimacy that is the key agent in predicting greater marital intimacy and well-being. Without spiritual meaning as a product of one’s relationship with God, marital intimacy and well-being can be negatively affected.

When spiritual meaning is not included in the model the spiritual intimacy to well-being relationship is strongly positive. However, when spiritual meaning is added, the direct positive connections of spiritual intimacy to marital intimacy or to well-being become negative. Thus, spiritual intimacy primarily predicts spiritual meaning, and what remains from spiritual intimacy predicts well-being and marital intimacy only weakly. However, although the direct negative relationships of spiritual intimacy to marital intimacy and to well-being after spiritual meaning was included in the model are counterintuitive and do not match our original conceptual model (Figure 1), the connections between spiritual intimacy and both well-being and marital intimacy through spiritual meaning are in the expected direction, and substantially stronger than the direct pathways in the model without spiritual meaning.

Meaning in life

The strength of the mediational pathway through spiritual meaning suggests that perceived spiritual intimacy is important largely because it gives meaning to a person’s life, providing a sense of connection to a higher power who is believed to care for us, enabling positive religious coping (Pargament, Tarakeshwar, Ellison, & Wulff, 2001). This is consistent with Wnuk and Marcinkowski (2014) findings that hope and meaning in life are mediators between spiritual experiences and the life satisfaction portion of well-being and affirms the observed relative importance of life satisfaction to the latent variable of well-being in the model used here.

Baumeister, Vohs, Aaker, and Garbinsky (2013) examining life satisfaction found that happiness was associated with being a taker, whereas meaningfulness was associated with being a giver. The “giver” construct parallels Wachs and Cordova’s (2007) descriptions of being attuned to the concerns and needs of others which, in turn promotes marital intimacy, and also with Dollahite and Marks’ (2009) descriptions of the selfless priorities of faith and family as a manifestation of sacred meaning in life. Stafford & McPherson (2014) include sacrifice as an important factor in what they term “sanctity of marriage.” Together, these provide a possible explanation for how spiritual meaning—through the modeling of selfless giving—is associated with both well-being and marital intimacy.

From a different perspective, Van Tongeren, Hook, and Davis (2013) found that spiritual meaning was enhanced by what they termed “defensive” religious beliefs—those that provided solace, comfort, and stability—rather than existential beliefs that are less rooted in the present. This enhanced spiritual meaning resulted from commitment to one’s religious community and its validation of one’s attachment to God. This suggests another possible mechanism for explaining how spiritual meaning—birthed from tangible personal experiences with God—might enhance both marital intimacy and well-being.

Spiritual intimacy without meaning

A finding we did not initially anticipate was that spiritual intimacy would be associated with poorer marital intimacy and poorer well-being once spiritual meaning was accounted for. Why is spiritual intimacy without meaning associated with negative outcomes? At least two areas in the religion and health literature not included in the model suggest possible explanations, and in light of the findings are important to discuss: the constructs of negative religious coping and extrinsic religiosity. The focus in this study is on positive religious coping, but religiously-oriented yet maladaptive coping strategies also exist and may contribute to the portrait of someone high on spiritual intimacy. These elements are unlikely to contribute much to spiritual meaning, but may nonetheless influence the nature of one’s spiritual intimacy and thus might help explain this study’s findings of weak, negative direct links from spiritual intimacy to marital intimacy and to well-being coupled with strong, positive indirect links to those same outcomes via spiritual meaning

Negative religious coping

Negative religious coping has indeed been shown to have deleterious effects on both interpersonal relationships and well-being (Mahoney, Pargament, Tarakeshwar, & Swank, 2001). Despite positive religious coping acting as a buffer for romantic attachment or avoidance it does not attenuate the negative issues (Pollard et al., 2014). This could possibly explain the small negative direct path effect seen in our model as being due to ambivalence and inconsistency in one’s relationship to God. Another factor is that not all spouses are homogenous in their religious beliefs, which in turn, could create inconsistencies in whether spousal spiritual intimacy is a positive or negative factor for marital intimacy (Vaaler et al., 2009). Because the interplays between spiritual intimacy, spiritual meaning, marital intimacy, and well-being are complex, it is not surprising that the path coefficients initially seem contradictory.

Extrinsic religiosity

One must also consider extrinsic religiosity (outward religious observance), not included in this conceptualization of spiritual intimacy but which might help explain its direct negative associations with well-being and marital intimacy. Steffan (2014) found that extrinsic religiosity was related to increased maladaptive perfectionism and therefore contributed to decreased life satisfaction and increased negative affect. This might help to explain why, when the positive effects of religious coping and a perceived relationship to God working through meaning are removed from our model, what is left are the negative direct effects of spiritual intimacy on marital intimacy and well-being.

Study Strengths

Some of the strengths of this study include the large nationwide sample of Christians who believe in a personal God, and the increased uniformity in understanding of study questions because participants share the same conservative Christian faith (Seventh-day Adventism). This study also included a large number of older adults with long-term marital relationships thereby providing a perspective not typically included in studies of intimacy and allowing us to address this gap in the literature. The methodology included measurements that are well validated.

Study Limitations

Using archival data is not without challenges. Although these manifest variable measures are all valid and reliable, latent variable indicators were selected from what was available in the data set. Being able to more thoroughly define each latent variable and, in particular, to more fully explore the latent factor of spiritual meaning would have strengthened this study. Additionally, although the BRHS has two waves, only cross-sectional data from wave one was used because data from the second wave was not ready for analysis at the time this study was developed. The longitudinal relationships among these variables should be explored in order to better understand how perceived spiritual intimacy, marital intimacy, and well-being associate and influence each other through the different seasons of life.

Conclusions

Spiritual meaning was found to be the link connecting a relationship with God to a relationship with one’s spouse and to well-being. However, a relationship with God that is devoid of meaning may contribute to poorer well-being and a worse relationship with one’s spouse.

These findings highlight the importance of meaning to relationships, notably among spiritual intimacy, marital relationships, and well-being. This suggests the value of addressing spiritual meaning in whole-person health and wellness, as well as in one’s intimate marital relationships over the continuum of life. Further investigation is needed of the weak negative effect of spiritual intimacy apart from meaning when it operates on both well-being and marital intimacy, possibly by considering negative religious coping. In line with other studies, one might consider whether there is a point where an apparent perceived vertical intimacy with God, which does not add meaning to life, can impede one’s horizontal intimate relationships as alluded to by Vaaler et al. (2009) and Fincham et al. (2008). Within the bounds of Christianity, religion and its efficacy in life can be seen as a two-edged sword with both costs and benefits (Pargament, 2002).

Additionally, people do have meaningful lives outside Christianity, so further study of those who espouse some other faith or no religious faith is needed to better understand how spiritual meaning functions (Jirasek, 2013). How to best impart spiritual meaning without imposing one’s religious beliefs on others remains a challenge. The question also remains as to how current marital and spiritual intimacy paradigms will influence the lives of young adults and how this influence will be manifested over time in their lives, marriages, and families.

Contributor Information

Karen J. Holland, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University

Jerry W. Lee, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University

Helen H. Marshak, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University

Leslie R. Martin, La Sierra University

References

- Acker J, Davis JH. Intimacy, passion, and commitment in adult romantic relationships: A test of the triangular theory of love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9:21–50. doi: 10.1177/0265407592091002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmetoglu G, Swami V, Chamorro-Premuzic T. The relationship between dimensions of love, personality, and relationship length. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:1181–1190. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (Version 22) Chicago: SPSS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. On the psychosocial impact and mechanisms of spiritual modeling. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2003;13(3):167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Baesler EJ. Prayer and relationship with God II: Replication and extension of the relational prayer model. Review of Religious Research. 2002;44(1):58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Aaker JL, Garbinsky EN. Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2013;8(6):505–516. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.830764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler TL, Fraser GE, Beeson WL, Knutsen SF, Herring RP, Chan J, Jaceldo-Siegl Kl. Cohort profile: The Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37(2):260–265. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Carter P, Carter D. Emotional risk-taking in marital relationships: A phenomenological approach. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy: Innovations in Clinical and Educational Interventions. 2010;9(4):327–343. [Google Scholar]

- Charlemagne-Badal SJ, Lee JW, Butler TL, Fraser GE. Conceptual domains included in well-being and life satisfaction instruments: A review. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2014:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s11482-014-9306-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chelune GJ, Robison JT, Krommor MJ. A cognitive interaction model of intimate relationships. In: Derlega VJ, editor. Communication, Intimacy, and Close Relationship. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova J, Scott R. Intimacy: A behavioral interpretation. The Behavior Analyst. 2001;24(1):75–86. doi: 10.1007/BF03392020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G, Finch S. Inference by eye: Confidence intervals and how to read pictures of data. American Psychologist. 2005;60(2):170–180. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EB, Moriarty GL, Mauch JC. God images and God concepts: Definitions, development, and dynamics. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2013;5(1):51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ditzen B, Hoppmann C, Klumb P. Positive couple interactions and daily cortisol: On the stress-protecting role of intimacy. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(8):883–889. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318185c4fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollahite DC, Marks LD. A conceptual model of family and religious processes in highly religious families. Review of Religious Research. 2009;50(4):373–391. [Google Scholar]

- Dorian M, Cordova J. Coding intimacy in couples’ interactions. In: Kerig P, Baucom D, editors. Couple Observational Coding Systems. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley MG, Kosinski FA., Jr Religiosity and marital satisfaction: A research note. Review of Religious Research. 1990;32(1):78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Cheung C, Tehrani K. Assessing spirituality through personal goals: Implications for research on religion and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research. 1998;45(1–3):391–422. doi: 10.1023/A:1006926720976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA. Striving for the sacred: personal goals, life meaning, and religion. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61(4):731–745. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH, Lambert N, Stillman T, Braithwaite S. Spiritual behaviors and relationship satisfaction: A critical analysis of the role of prayer. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27(4):362–388. [Google Scholar]

- Gable S, Gonzaga G, Strachman A. Will you be there for me when things go right? Supportive responses to positive event disclosures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91(5):904–917. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable SL, Reis HT, Impett E, Asher ER. What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:228–245. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeff AP, Malherbe HL. Intimacy and marital satisfaction in spouses. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2001;27(3):247–257. doi: 10.1080/009262301750257100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch R, James D, Schumm W. Spiritual intimacy and marital satisfaction. Family Relations. 1986;35:539–545. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward RD, Kraus N. Patterns of change in prayer activity, expectancies, and contents during older adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2013;52(1):17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Heller PE, Wood B. The influence of religious and ethnic differences on marital intimacy; Intermarriage versus intramarriage. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2000;26(2):241–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2000.tb00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Impett EA, Beals KP, Peplau LA. Testing the investment model of relationship commitment and stability in a longitudinal study of married couples. (2001) Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, Social. 2001;20(4):312–326. [Google Scholar]

- Jirasek I. Verticality as non-religious spirituality. Implicit Religion. 2013;16(2):191–201. doi: 10.1558/imre.v16i2.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Parkerson GR, Meador KG. Religion index for psychiatric research. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(6):885–886. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.885b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Pietromonaco PR. Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(5):1238–1251. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. Marital intimacy among older persons: The spouse as confidant. Journal of Family Issues. 1988;9:273. doi: 10.1177/019251388009002008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Morton KR, Walters J, Bellinger DL, Wilson C, Fraser GE. Cohort profile: The biopsychosocial religion and health study (BRHS). [Research Support, N. I. H., Extramural] International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(6):1470–1478. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckow A, Ladd KL, Spilka B, McIntosh DN, Paloma M, Parks C, LaForett D. The structure of prayer: Explorations and confirmations. In: Hill PC, Hood WR, editors. Measures of Religiosity; Paper presented at the 1996 meeting of the American Psychological Association; Toronto, Canada. Birmingham, AL: Religious Education Press; 1999. pp. 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Tarakeshwar N, Swank AA. Religion in the home in the 1980s and 1990s: A meta-analytic review and conceptual analysis of links between religion, marriage, and parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(4):559–596. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascaro N, Rosen D, Morey L. The development, construct validity, and clinical utility of the spiritual meaning scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;37:845–860. doi: 10.1016/jpaid.2003.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Willoughby BL. Religion, self-regulation, and self- control: associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(1):69–93. doi: 10.1037/a0014213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirgain SA, Cordova JV. Emotion skills and marital health: The association between observed and self-reported emotion skills, intimacy, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2007;26(9):983–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Morton KR, Lee JW, Haviland MG, Fraser GE. Religious engagement in a risky family model predicting health in older black and white Seventh-day Adventists. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2012 Mar 5; doi: 10.1027/a0027553. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloma MM, Pendleton BF. The effects of prayer and prayer experiences on measures of general well-being. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1991;19(1):71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. Fetzer Institute, editor. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research: A Report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging; 1999. Religious/spiritual coping; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The bitter and the sweet: Evaluation of the costs and benefits of religiousness. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13(3):168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Tarakeshwar N, Ellison EG, Wulff KM. Religious coping among the religious: The relationships between religious coping and well-being in a national sample of Presbyterian clergy, elders, and members. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40(3):497–513. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard SE, Riggs SA, Hook JN. Mutual influences in adult romantic attachment, religious coping, and marital adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0036682. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Shaver P. Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In: Duck S, editor. Handbook of Personal Relationships. Chichester, England: Wiley; 1988. pp. 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CC, Singer BH, Palmersheim KA. Social inequalities in health and well-being: The role of relational and religious protective factors. In: Grim O, Ryff C, Kessler R, editors. How Healthy Are We? A National Study of Well-being at Midlife. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 90–123. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DJ. Pocket guide to interpersonal neurobiology. New York, NY: Norton; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Silberman I. Spiritual role modeling: The teaching of meaning systems. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2003;13(3):174–195. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DB, Newman JL, Fuqua DR. Understanding the role of relational factors in Christian spirituality. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 2008;36(2):124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sneed J, Whitbourne S, Schwartz S, Huang S. The relationship between identity, intimacy, and midlife well-being: Findings from the Rochester adult longitudinal study. Psychology and Aging. 2011;27(2):318–323. doi: 10.1037/a0026378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford L, David P, McPherson S. Sanctity of marriage and marital quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2014;31(1):54–70. doi: 10.1177/0265407513486975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steffan PR. Perfectionism and life aspirations in intrinsically and extrinsically religious individuals. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53(4):945–958. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroope S, McFarland MJ, Uecker JE. Marital characteristics and the sexual relationships of older U.S. adults: An analysis of National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project data. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0379-y. Online first edition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaaler ML, Ellison CG, Powers DA. Religious influences on the risk of marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(4):917–934. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tongeren DR, Hook JH, Davis DE. Defensive religion as a source of meaning in life: A dual meditational model. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2013;5(3):227–232. doi: 10.1037/a0032695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wachs K, Cordova J. Mindful relating: Exploring mindfulness and emotion repertoires in intimate relationships. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2007;33(4):464–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12® Health Survey (With a Supplement Documenting Version 1) Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wnuk N, Marcinkowski JT. Do existential variables mediate between religious-spiritual facets of functionality and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health. 2012;53:56–67. doi: 10.1007/s10943-2012-9597-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]