Abstract

Chromatographic purification of chromium (Cr), which is required for high-precision isotope analysis, is complicated by the presence of multiple Cr-species with different effective charges in the acid digested sample aliquots. The differing ion exchange selectivity and sluggish reaction rates of these species can result in incomplete Cr recovery during chromatographic purification. Because of large mass-dependent inter-species isotope fractionation, incomplete recovery can affect the accuracy of high-precision Cr isotope analysis. Here, we demonstrate widely differing cation distribution coefficients of Cr(III)-species (Cr3+, CrCl2+ and CrCl2+) with equilibrium mass-dependent isotope fractionation spanning a range of ~1‰/amu and consistent with theory. The heaviest isotopes partition into Cr3+, intermediates in CrCl2+ and the lightest in CrCl2+/CrCl3°. Thus, for a typical reported loss of ~25% Cr (in the form of Cr3+) through chromatographic purification, this translates into 185 ppm/amu offset in the stable Cr isotope ratio of the residual sample. Depending on the validity of the mass-bias correction during isotope analysis, this further results in artificial mass-independent effects in the mass-bias corrected 53Cr/52Cr (μ53 Cr* of 5.2 ppm) and 54Cr/52Cr (μ54Cr* of 13.5 ppm) components used to infer chronometric and nucleosynthetic information in meteorites. To mitigate these fractionation effects, we developed strategic chemical sample pre-treatment procedures that ensure high and reproducible Cr recovery. This is achieved either through 1) effective promotion of Cr3+ by >5 days exposure to HNO3 —H2O2 solutions at room temperature, resulting in >~98% Cr recovery for most types of sample matrices tested using a cationic chromatographic retention strategy, or 2) formation of Cr(III)-Cl complexes through exposure to concentrated HCl at high temperature (>120 °C) for several hours, resulting in >97.5% Cr recovery using a chromatographic elution strategy that takes advantage of the slow reaction kinetics of de-chlorination of Cr in dilute HCl at room temperature. These procedures significantly improve cation chromatographic purification of Cr over previous methods and allow for high-purity Cr isotope analysis with a total recovery of >95%.

Keywords: Chromatographic purification, Isotope fractionation, Chromium speciation, High-precision isotope analysis, Chromium distribution coefficient

1. Introduction

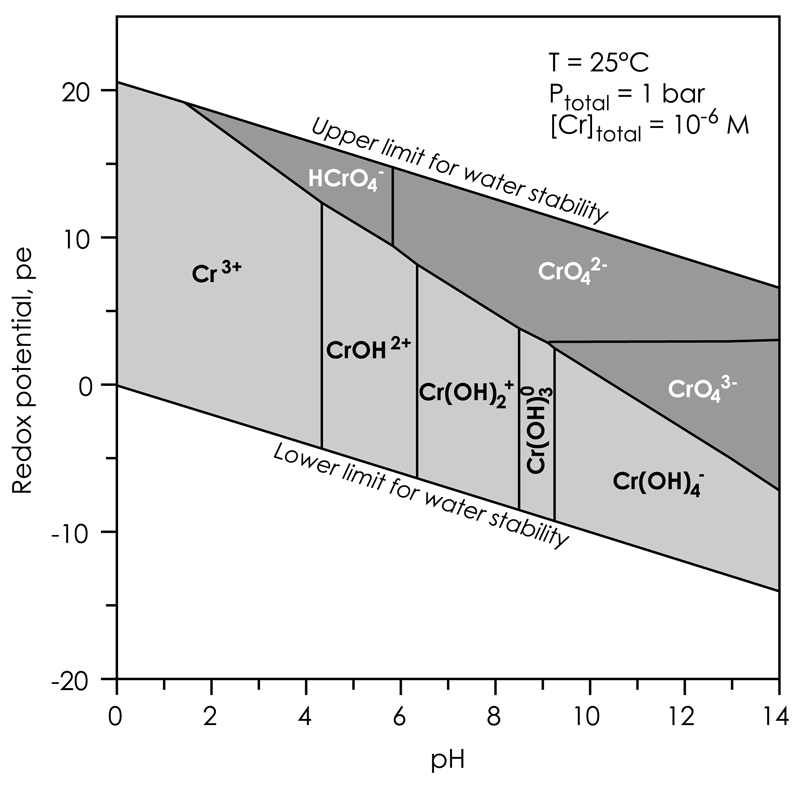

Chromium is a redox-sensitive transition-group element with four stable isotopes at masses 50, 52, 53 and 54. It mainly occurs in two oxidation states, Cr(III) and Cr(VI), with the tri-valent form as the major substituent in rock-forming minerals such as oxides, oxy-hydroxides and silicates. The hexa-valent form is toxic and, thus, a significant threat to groundwater systems. In natural aqueous environments, Cr(III) exists as hydrolyzed hexa-aqua-Cr3+ (Cr[H2O]63+) and its hydroxy-complexes, CrOH2+, Cr(OH)2+, Cr(OH)3° and Cr(OH)4−, whereas Cr(VI) exists as the oxy-anions HCrO4−, CrO42− and CrO43−. Their speciation is controlled by the prevailing oxidation potential (pe) and pH conditions (Fig. 1). Cr(III) is predominant under moderately oxidizing to reducing conditions over a wide pH range, whereas Cr(VI) dominates the speciation under strongly oxidizing conditions. The availability of other complexing ligands, such as Cl−, NO3−, Br− and SO42−, further affects the speciation of Cr. Their influence becomes important when evaluating Cr speciation of acid-digested rock samples. This speciation governs the elution characteristics of Cr from ion chromatographic columns, which is used for its chemical purification prior to isotope analysis using Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS) and Multiple Collection Inductively Coupled Plasma-source Mass Spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS).

Fig. 1.

Pourbaix diagram for aqueous Cr species at 25 °C and 1 bar with a total Cr concentration of 10−6 M. Predominance areas for aqueous Cr(III) and Cr(VI) species are shown in light- and dark-gray shades, respectively.

Measurements of the mass-dependent chromium isotope fractionation in ancient terrestrial rocks, has provided information about the geochemical cycling of chromium [1], the oxidative state of ancient oceans and atmospheres [2,3], as well as the extraterrestrial origin of the K-T impactor [4]. In addition to these terrestrial geochemical applications, Cr isotope variability in meteorites is used to determine the chronology and nucleosynthetic diversity of early solar system materials. The presence of radiogenic anomalies in 53Cr, derived from the ancient decay of the short-lived 53Mn radionuclide, allows for the dating of meteoritic materials. Nucleosynthetic anomalies in the neutron-rich 54Cr isotope are used for correlative studies of meteorite groups [5–7], assessment of the nucleosynthetic sources that have contributed to the solar system [8], and studies of nebular thermal processing [9].

A reliable evaluation of such processes requires accurate isotope analysis using mass spectrometric techniques such as TIMS, MC-ICP-MS and Secondary Ionization Mass Spectrometry (SIMS). Here we focus on the chemical purification procedures required for accurate and reproducible TIMS and MC-ICP-MS analysis. Quantitative separation of high purity Cr for high-precision isotope analysis is complicated by the potential presence of multiple Cr-hydration, oxidation complexes and Cr-ligand species [10]. Differences in the effective charge and radius of these complexes results in varying selectivity during ion exchange reactions, while the generally sluggish reaction kinetics of Cr-ligand complexation makes a quantitative evaluation of their relative abundances unpredictable. This generates variable ion chromatographic elution characteristics that often result in significant losses of Cr during chemical purification (Table 1).

Table 1.

Chromatographic separation protocols used for Cr purification prior to high-precision isotope analysis.

| Promoted Cr redox state | Ion exchanger | Sample pre-treatment procedure | % Crrecovery | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr(III) | 2x AG1-x8 col’s | 1) 2.5% HF load 2) 9M HCI (steam bath) |

? | [52] |

| 2x AG50w-x8 col’s | 1 + 2) 1 M HCl load | ? | [14] | |

| Mitsubishi AGx8 | 1 M HCl load | ~70 | [53]; similar to [14] | |

| 2x AG50w-x8 | 1) 6 M HCl at 100°C, 1 M HCl load 2) 0.15 M HNO3 load |

>80 | [15]; based on [14] | |

| AG50w-x8 | Hot 6 M HCl, 0.5 M HCl load | ? | [44]; based on [14,15] | |

| 3x AG50w-x8 col’s | 1 + 2) 1 M HCl load 3) HNO3 load |

>90 | [1]; modified from [14,53,54,45] | |

| 3x AG50w-x8 col’s | 1) 2 M HNO3 2) 6 M HCl at 100°C, 1 M HCl load 3) 0.15 M HNO3 load |

~80 | [6]; based on [53,15] | |

| AG1-x8/AG50w-x8 | 1) 6 M HCl at 150°C, 6 M HCl load 2) 0.5 M HCl load |

~80 | [8]; based on [14] | |

| AG1-x8/AG50w-x8/2xTODGA/AG1-x8 | 1) 6 M HCl load 2) Hot 6 M HCl for 12 h, 0.5 M HCl load 3) 14 M HNO3 load 4) 8 M HCl load 5) 6 M HCl load |

? | [23] | |

| Cr(VI) | AG1-x8/AG50w-x8 | 1) 5 M HNO3 load, reductive Cr elution w/2 M HNO3 2) Dilute HNO3 load |

? | [11] |

| AG1-x8 | Dilute HCl load, reductive Cr elution w/0.1 M H2SO3 | ? | [12]; modified from [11] | |

| AG1-x8 | Dilute HCl (pH = 1–3) load, reductive Cr elution w/sulfurous acid | ? | [19,55]; adopted from [12] | |

| AG1-x8 | 0.2 M (NH4)S2O8 load, reductive Cr elution w/2 M HNO3 | ? | [56]; modified from [11] | |

| AG1-x12/AG1-x8 | 1) 6M HCl load 2) Dilute HCl + (NH4)S2O8 load, reductive Cr elution w/2 M HNO3 +H2O2 |

80–90 | [2,3,57]; modified from [12,13] | |

| AG1-x8 | Cr reduction w/Fe(II), 6 M HCl load | >95 | [20]; similar to [2] | |

| AG1-x8 | Cr oxidation w/(NH4)2S2O8 at 120–130°C, | 80–90 | [24]; modified from [11,13,58] | |

| 0.025 M HCl + 0.02 M (NH4)2S2O8 load, reductive elution w/2 M HNO3 | ||||

| AG1-x8 | Dilute HNO3 load, reductive Cr elution w/2 M HNO3 | 92–96 | [41]; modified from [24,11] | |

| AG1-x8 | Dilute HNO3 + NH4OH (pH = 8) load, reductive Cr elution w/6 M HCl + H2O2 | ? | [22,59] | |

| AG1-x8 | Dilute HNO3, pH adjusted to 8 + high pe w/NH4OH + H2O2 | 90–95 | [25] | |

| AG1-x8 | Dilute HCl load, reductive elution w/2M HNO3 +0.6% H2O2 | ? | [42] | |

| Cr(VI) & Cr(III) | 2x AG1-x8 /AG50w-x8/AG1-x8 | 1) 6M HCl load 2) Dilute HNO3 +(NH4)2S2O8, reductive Cr elution w/2 M HNO3; 3) 0.1 M HNO3 load 4) 0.1 M HCl load |

95–99 | [13]; modified from [58,11] |

| AG1-x8/2xAG50w-x8 | 1) 6 M HCl load 2) 6 M HCl at 80°C, 1 M HCl load 3) 0.7 M HNO3 at 80–100°C, 0.5 M HNO3 load |

~86–90 | [45] | |

| AG1-x8/AG50w-x8 | 1) Dilute HCl load, reductive Cr elution w/6M HCl + H2O2 2) Dilute HNO3 load |

? | [21]; based on [12,19,6] |

Two principal ion exchange Cr separation methods have been reported in the literature, either utilizing anion or cation exchange procedures. The first method relies on anion exchange separations of oxidized Cr(VI)-species in the form of oxy-anions from the sample matrix, in which Cr(VI) is retained on the positively charged functional groups of the resin (e.g. [11–13]). These chromatographic protocols typically result in 80–95% Cr recovery (Table 1 and references therein), with the incomplete recovery often associated with the reduction/oxidation protocols involved in the elution sequence. The second method relies on cation exchange separation of the reduced Cr(III) redox state and has found application mostly in cosmochemical studies of radiogenic and nucleosynthetic anomalies (e.g. [14,15,6]). Employing a cationic exchanger avoids the oxidation step of Cr, which is already predominantly in its trivalent form following conventional sample digestion procedures using HF-HNO3 and HCl-HNO3. Following these protocols, the Cr recovery ranges from 70% to about 90% (Table 1), with the incomplete recovery associated with complex Cr(III)-speciation in the acid-digested sample aliquots prior to chromatographic separation. Controlling this chemical speciation is the main focus of the present study.

Preferential loss of specific Cr species, and thus incomplete recovery, can introduce significant equilibrium stable isotope fractionation. This results mainly from small differences in the vibrational frequencies of isotopes [16,17]. Fractionation is most pronounced for substances in which the element resides in configurations with very different bonding environment, where the heavier isotopes preferentially partition into sites that form strong and short chemical bonds typical of a lower coordination environment [18]. The small energy associated with isotope exchange between two substances results in unequal equilibrium partitioning of the isotopes, i.e. equilibrium isotope fractionation.

Experimental evidence shows that mass-dependent isotope fractionation associated with Cr redox reactions is significant, i.e. apparent excess δ53(δ53Cr = [(53Cr/52Cr)sample/(53Cr/52Cr)standard − 1] × 103 in Cr(VI)-bearing species of up to several permil (e.g. [12,19,2,20–22]), qualitatively consistent with theoretical predictions [18]. Specifically, Ellis et al. [12] found 3–4‰ fractionations in laboratory experiments where Cr(VI) was reduced to Cr(III). For a typical loss of 10–20% Cr in the form of Cr(VI), this corresponds to about 0.3–0.8‰ deficit in the 53Cr/52Cr ratio in the collected Cr fraction, which is 6–16 times larger than the uncertainty reported for high-precision Cr isotope analysis (of un-spiked samples) using MC-ICP-MS [23]. This highlights that inefficient Cr recovery and preferential loss of one of the Cr redox pairs during anionic chromatographic purification can result in significant stable isotope fractionations. Cationic exchange procedures, on the other hand, do not rely on Cr-oxidation and therefore avoid the large isotope fractionations known to be associated with Cr redox processes. Such techniques are therefore preferred when purifying Cr from sample matrices with radiogenic and nucleosynthetic effects, such as meteoritic materials where double spiking is inappropriate. Instead, the cation exchange procedures rely on the slow reaction kinetics of Cr(III) speciation at room temperature and the promotion of Cr(III) species with appropriate selectivities for the cation exchanger prior to column loading. Formation of such species with different vibrational frequencies of their Cr(III)-ligand bonds is predicted to generate significantly smaller stable isotope effects than the fractionations imposed between the Cr(III)-Cr(VI) redox pairs. Theoretical considerations of the vibrational frequencies of Cr isotope pairs in Cr species predict only moderate fractionation associated with Cr(III)-ligand complexation, e.g. with chlorine [18], i.e. a factor of 2–3 lower than that associated with Cr redox reactions. Although the limited fractionation remains an important advantage over anion exchange methods, the typical pervasive loss (10–30%; Table 1) of fractionated Cr can still compromise measurement accuracy.

When applied to the purely mass-dependent anomalies characteristic of terrestrial samples, such procedural isotope fractionation effects are mostly corrected by isotope double spike techniques (e.g. [24,25]). Double spiking, however, precludes any determination of the radiogenic and nucleosynthetic anomalies characteristic of meteoritic materials that must instead rely on consistently high Cr recoveries. For these un-spiked samples, the large mass-dependent isotope fractionations induced through chromatography can result in apparent mass-independent artifacts with superficial similarities to the nucleosynthetic and radiogenic isotope anomalies found in meteoritic materials (e.g. [26]). If the Cr recovery is <95%, these artifacts become significant at the ~6 to 15 ppm reproducibility level on μ54Cr* characteristic of modern mass spectrometric methods [27,15,23]. Recoveries in excess of 95%, however, are rarely achieved using modern chromatographic purification methods (Table 1) and, as mass spectrometric methods improve, such artifacts may become the main source of error in the study of mass-independent isotope anomalies in meteorites.

Despite these caveats, little attention has been given to describing and controlling the speciation of Cr, which governs its complex chromatographic elution characteristics. This is also typical for many other transition metals, such as Mo, W, Ru and V, whose chromatographic properties are likewise complicated by multiple oxidation states and availability of species with variable effective charge dependencies (e.g. [28]). The quantitative difference in relative selectivity of various Cr complexes for ion exchangers and the influence of their solution speciation on the elution efficiency of Cr is virtually unexplored. Here, we report on the first experimental determination of the distribution coefficients of Cr(III)-species in acidic media for a cation exchanger and show how uncontrolled Cr speciation can result in insufficient Cr recovery through loss of Cr(III)-species from chromatographic columns. We further demonstrate the existence of stable Cr isotope fractionation spanning a range of ~1‰/amu between Cr(III)-species in solution as well as intra-peak chromatographic isotope fractionations. This allows us to evaluate the influence of selective recovery of Cr species from chromatographic columns on the isotope composition of the collected Cr fraction and, hence, the accuracy of Cr isotope measurements. Finally, we propose various chemical sample pre-treatment strategies for promoting the predominance of specific Cr-species in solution prior to column loading, and use this information to develop improved chemical procedures for reproducible high Cr recoveries. These procedures, which provides unsurpassed Cr recoveries relative to earlier protocols, can also be exploited for sufficient and reliable separation of Cr from other elements, such as Mg, Ti and Fe, whose isotopic analysis suffers from direct isobaric or doubly charged interferences on their isotopes (e.g. 50Cr on 50Ti, 54Cr on 54Fe, 52Cr++ on 26Mg and 50Cr++ on 25Mg).

2. Methods and analytical procedures

2.1. Samples analyzed, experimental solutions, ion exchange resins and chemical procedures

In order to test the efficiency and reproducibility of our chemical procedures, we choose samples and terrestrial rock standards with varied chemical compositions, as well as high-purity certified CPI International Peak Performance™ standard stock solutions. These include powders of terrestrial rock standards (BIR-1, DTS-2B, DNC-1) and crushed meteorite specimens, including two Ca-Al-rich inclusions (CAIs), an ordinary chondrite (Alfianello), carbonaceous chondrites (Ivuna, Allende, NWA 6043 and NWA 5958) and one ureilite meteorite (NWA 7686). Samples were transferred to pre-cleaned Savillex PFA beakers, digested in concentrated HF-HNO3 (3:1) on a hot plate at 120 °C for >2 days, evaporated to dryness and subsequently dissolved in aqua regia (HCl:HNO3 [3:1]) at 120 °C for another 2 days in order to destroy any fluorides formed during HF-HNO3 digestion and again evaporated to dryness. The aqua regia treatment was repeated until there were no remaining solids. The sample aliquots were then converted to the appropriate ionic form (Cl− or NO3−) using either HCl or HNO3 acid prior to chromatographic separation. Chromatographic gravity-flow columns were packed with AG50w-x8 200–400 mesh cation exchange resins from Bio-rad Laboratories. All chromatographic experiments were carried out at room temperature.

2.2. High-resolution chromatographic separation experiments to determine distribution coefficients, KD, of Cr(III)-species

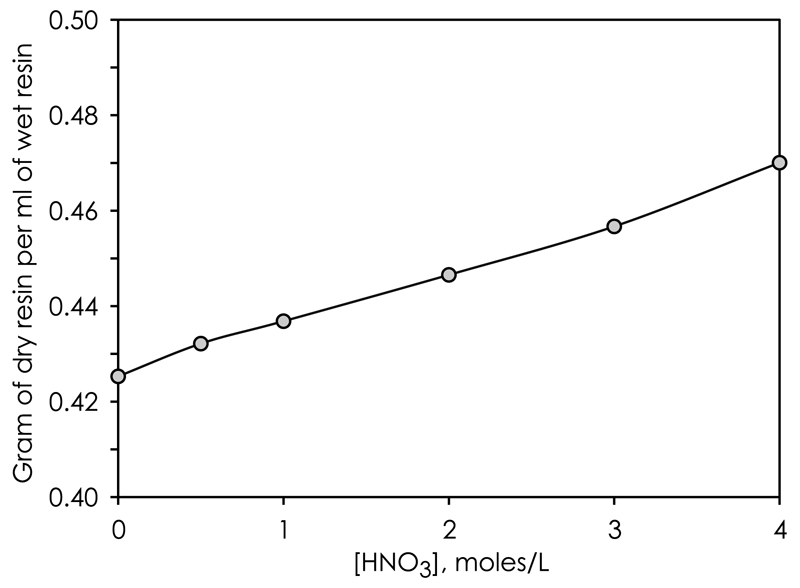

We calculated the distribution coefficients (KD values) of various Cr(III)-species and their separation efficiency from matrix elements such as Na, Ni and Mg through a series of high-resolution (120 × 3.2 mm ID Savillex PFA columns) chromatographic elution experiments. Mixtures of synthetic CPI International Peak Performance™ standards were prepared with 10 μg of each element, converted to Cl-form in 6 M HCl and loaded in 0.2 column volumes (CV) of 0.5 M HCl onto 965 μl of AG50w-x8 200–400 mesh resin. The total cation load on the column corresponds to about 0.1% of the resins total cation exchange capacity (CEC), thereby safely preventing peak fronting effects [29], which would otherwise compromise the accuracy of KD values deduced from peak maxima. At KD <10, tailing effects on elution peaks are negligible. Chromatographic elution experiments are therefore particularly useful for determination of distribution coefficients when KD <10. For higher KD values, batch equilibration experiments are preferred [29]. For precise determination of the position of peak maxima, eluents (0.5 M, 1.0 M, 2.0 M, 3.0 M and 4.0 M HNO3 and 0.5 M HCl) were collected in fractions of 0.25–2CVs depending on estimated peak widths. Elemental concentrations in each collect were determined on a Thermo Scientific XSeries quadrupole ICP-MS at the Centre for Star and Planet Formation, University of Copenhagen. Peak maximum positions were determined by gauss-fitting. To account for acid-wetted density differences of the cation resin, a known mass of oven-dry (80 °C) resin (8.04 g) was mixed with the eluting acids of variable molarity (0.5 M, 1.0 M, 2.0 M, 3.0 M and 4.0 M HNO3 and 0.5 M HCl) and their acid-wetted resin densities were determined on graduated columns (Fig. 2). These density differences were accounted for when calculating distribution coefficients of various exchange species.

Fig. 2.

Acid-wetted AG50w-x8 200–400 mesh resin densities in HNO3 solutions.

2.3. Experimental and analytical procedures for Cr isotope analysis

The magnitude of chromium isotope fractionation between Cr(III)-species in solution, as well as on-column intra-peak isotope fractionation, was determined by processing a pure CPI International Peak Performance™ Cr standard through a high-resolution AG50w-x8 200–400 mesh resin-filled column (120 × 3.2 mm ID). The Cr isotope composition of separate peak fractions was analyzed on the Thermo Finnigan Neptune Plus Multiple-Collector Inductively-Coupled-Plasma Mass-Spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) at the Centre for Star and Planet Formation, University of Copenhagen, according to procedures described in Schiller et al. [23]. Samples were introduced into the plasma in 2.5% HNO3 through an ESI Apex IR desolvating nebulizer. To minimize interferences from ArN, we used Trifluoromethane (CHF3) as supplementary gas instead of N2. Potential direct isobaric interferences (50Ti, 50V, and 54Fe) on 50Cr and 54Cr were corrected for by monitoring 49Ti, 51V, and 56Fe. A 500 ppb Cr solution yielded a typical 52Cr ion beam intensity of about 30 V and beam intensities of standard and sample were matched to within 5%. Each sample was analyzed 1–3 times (100 scans integrated over 16.67 s, spaced with 1259 s of baseline measurement). The unprocessed CPI International Peak Performance™ Cr standard was used as a bracketing standard.

Isotope data was reduced using the freeware software package Iolite [30] that runs within Igor Pro by means of a modified data reduction scheme tailored for Cr isotope data acquired on a Thermo-Finnigan Neptune MC-ICP-MS [23]. Isotopic ratios of samples are presented as deviations from the unprocessed Cr standard in delta (δ) notation as parts per thousand (‰) according to δ5xCrsmp = [(5xCr/52Cr)smp/(5xCr/52Cr)std − 1] × 103, where ‘std’ represents the bracketing CPI Cr standard, ‘smp’ the sample and x represents either 0, 3 or 4. The mass-independent component of 53Cr/52Cr (μ53Cr*) and 54Cr/52Cr (μ54Cr*) variability is reported in the same fashion, but in the μ notation as parts per million (ppm) deviation from the exponential mass fractionation law, by internal normalization to 50Cr/52Cr = 0.051859. We here refer to ‘mass-independent’ as an artificial mass-independent effect resulting from inappropriate mass fractionation correction of a non-kinetic mass-dependent fractionation process.

2.4. Chemical solution speciation modeling and experimental determination of Cr speciation usingion chromatography

The geochemical speciation modeling software, PHREEQC [31], was employed for determining Cr speciation in HNO3 and HCl acid media as a function of temperature. We used equilibrium constants from the llnl.dat speciation database. Chromium predominance diagrams were calculated using the freely available PhreePlot software [32], which employs the speciation model from PHREEQC.

A series of chemical sample pre-treatment experiments were carried out in order to evaluate the kinetic control on Cr solution speciation in HCl and HNO3 acid media. For these experiments, we used our determined KD values for individual Cr(III)-species to separate them on fast-flowing chromatographic columns (40 × 8 mm ID, Bio-rad Laboratories) packed with 2 ml AG50w-x8 200–400 mesh resin. The abundance of Cr species eluted with individual elution peaks was determined using a Thermo Scientific XSeries quadrupole ICP-MS at the Centre for Star and Planet Formation, University of Copenhagen.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Cr speciation in HNO3 and HCl acid solutions as a function of temperature

The detailed solution speciation of en element for chromatographic separation governs its elution characteristics through an ion exchange column. Prior to conventional ion chromatographic purification of Cr for isotope analysis, samples are typically dissolved in hydrochloric or nitric acid media. The chlorinated or nitrated Cr complexes formed thus have different affinities for the ion exchange functional groups. Hence, in order to evaluate the chemical sample pre-treatment procedures required for en effective Cr chromatographic elution strategy, we first explore the equilibrium speciation of Cr in HCl and HNO3 solutions.

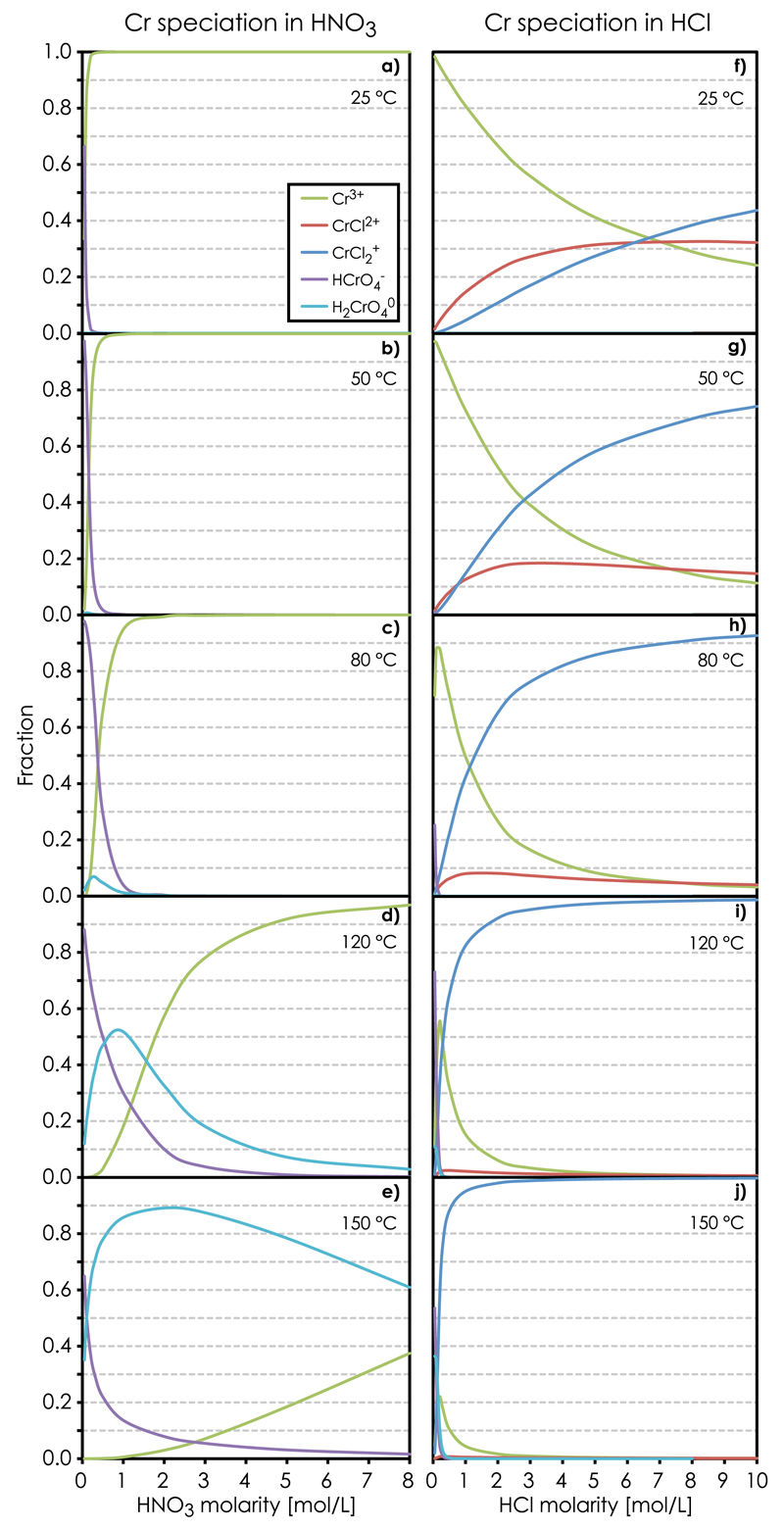

Our PHREEQC speciation modeling shows that Cr3+ is the predominant species in room temperature nitric acid solutions (Fig. 3). Cr3+ remains the dominant species at <80 °C and >0.4M HNO3. It does not form complexes with NO3−, which rather functions as an oxidizing agent, thereby promoting formation of Cr(VI) complexes (in the form of HCrO4− and H2CrO4°) with increasing temperature. Cr(VI) becomes the dominant oxidation state at >150 °C and <9 M HNO3. This is in accordance with experiments showing that Cr(H2O)63+ is the primary reaction product after Cr(VI) exposure to dilute HNO3 [33].

Fig. 3.

PHREEQC equilibrium Cr speciation model showing the abundance of Cr[III] (Cr3+, CrCl2+, CrCl2+) and Cr[VI] (HCrO4−, H2CrO4°) species in, a–e) HNO3 and f–j) HCl solutions as a function oftemperature.

In hydrochloric acid solutions, on the other hand, the PHREEQC model shows three principal Cr-species, including CrCl2+, CrCl2+ and Cr3+ (Fig. 3f–j). The strong bonds associated with chlorinated Cr complexes results in efficient Cr(III)-Cl complexation with Cl-coordination number increasing with HCl concentration [34]. Fig. 3 shows that CrCl2+ becomes the dominant Cr species at >120 °C and >0.5 M HCl. Cr(VI) is only present in solutions with sufficiently low hydrochloric acid molarity (<0.1 M HCl) and at >120 °C. The identity of the hydrated Cr(III)-species, Cr(H2O)4Cl2+, Cr(H2O)5Cl2+ and Cr(H2O)63+, was verified by radiometric gamma ray counting on 51Cr in HCl solutions [10,35]. In addition to these species, a neutral Cr(III)-Cl complex, interpreted as Cr(H2O)3Cl3°, was identified in Cr solutions reacted with concentrated hydrochloric acid (e.g. [36,37,33,35]). This neutral specie was not implemented in our PHREEQC model because of the lack of sufficient thermodynamic data for calculating the dependence of the equilibrium constant on temperature. However, experiments show that Cr(H2O)3Cl3° slowly decomposes through hydration and de-chlorination in dilute HCl, thereby eventually promoting formation of the trivalent Cr(H2O)63+ species [33]. Thus, while Cr(III) speciation in HNO3 acid is relatively simple, three principal reactions describe de-chlorination of Cr(III) complexes in HCl solutions according to:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Hence, chloride ions gradually displace coordinated water molecules in the ligand sphere, thereby forming chlorinated Cr(III)-species with charges decreasing in order of increasing ligand number. The sorbability, and hence distribution coefficients (KD), of these species for a cation exchanger therefore strongly depends on the activity of chloride ions.

3.2. Partitioning of Cr(III)-species for a cation exchange resin

During cation exchange chromatography, species elute in order of increasing selectivity, which broadly equates to the degree of positive charge (e.g. [38]). The Cr(III)-species are thus expected to elute in the order Cr(H2O)3Cl3°, Cr(H2O)4Cl2+, Cr(H2O)5Cl2+ and Cr(H2O)63+. The neutral Cr(H2O)3Cl3° specie does not exchange for the protonated functional groups on the resin (R-), while the positively charged species exchange according to:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where R- represents the sulfonated functional group on the cation exchanger. The sorbability of a species on an exchanger is expressed as the distribution coefficient, KD, which is given as the equilibrium molar ratio of the species in the solid (resin) phase to that in the solution, i.e. [R-Cr(H2O)6-nCln]/[Cr(H2O)6-nCln], where n is the number of Cl− ions in the ligand sphere. It has been shown that the distribution coefficient can be calculated from chromatographic elution experiments using the following relationship [39]:

| (7) |

where VpeakMax represents the retention volume [ml] of an exchanging specie (i.e. the eluent pore volume required for elution ofthe peak maximum), Vint, the interstitial pore volume of the resin-filled column, ρR, the acid-wetted resin density [g/ml], and VR represents the resin-filled (acid-wetted) column volume [ml]. We used this expression to calculate the distribution coefficients of Cr(III)-species and some matrix elements (Na, Mg and Ni) for the AG50w-x8 cation exchanger.

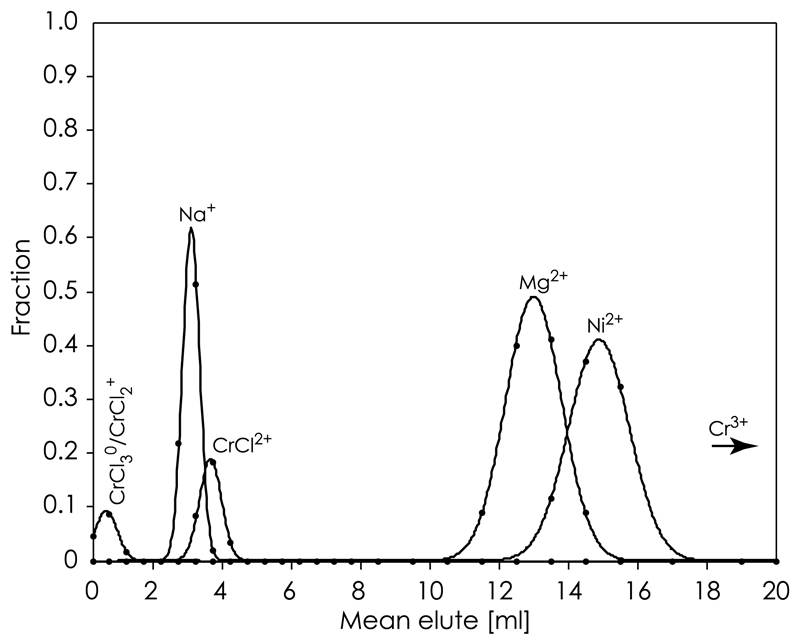

To ensure the presence of all cationic Cr(III)-species (CrCl2+, CrCl2+ and Cr3+) in the test solutions prior to column loading and accounting for the extremely sluggish reaction kinetics of Cr(III)-Cl speciation, we used a Cr standard stock solution which had equilibrated for several months in 6 M HCl at room temperature. Under these conditions, CrCl2+, CrCl2+ and Cr3+ should be present in about equal quantities (Fig. 3). Indeed, selective separation of Cr(III)-species on the cation exchanger demonstrated the presence of three resolvable elution peaks, representing CrCl2+, CrCl2+ and Cr3+, in order of increased charge and thus selectivity for the exchanger.

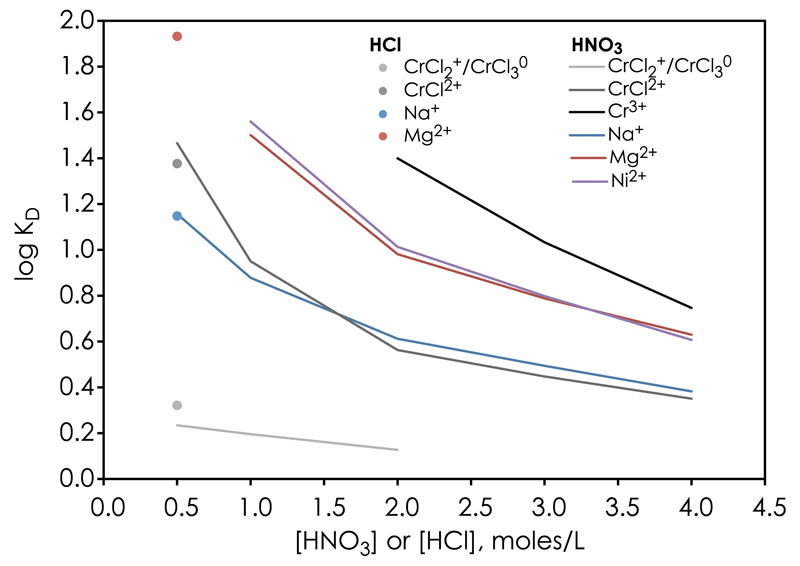

Table 2 shows the distribution coefficients, KD, computed from high-resolution chromatographic elution experiments by gauss-fitting to successive elution peaks. These values are in agreement with predictions for elution order based on their effective charge distribution, i.e. highly charged species have high KD values and vice versa. Fig. 4 shows an example chromatogram of an elution sequence of Cr(III)-species eluted with 1 M HNO3. Because of the low selectivity of the CrCl2+ specie for the cation exchanger, the resolution of our chromatographic columns does not allow us to distinguish between the neutral and mono-valent Cr complexes. Therefore, the KD values reported in Table 2 for CrCl2+ can be regarded as upper limits and either the CrCl2+ or CrCl3° species or both may represent the first elution peak, followed by CrCl2+ and lastly Cr3+. The KD values reported for Cr(III) on the cation AG50w-x8 resin (e.g. [38,40]) may be regarded as intermediates between the values reported for individual Cr(III)-species in this study. In section 5, we exploit these KD values for Cr(III)-species to predict their elution sequence from a cation exchanger and discuss plausible chromatographic separation strategies for Cr in order to gain a high recovery.

Table 2.

Distribution coefficients, KD, of Cr(III)-species (Cr3+, CrCl2+, CrCl2+) and some common cations in rock sample matrices (Na+, Mg2+, Ni2+) for an AG50w-x8 cation exchanger.

| HNO3 [M] |

HCl [M] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specie | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 0.5 |

| CrCl2+ | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.3 | – | – | 2.1 |

| CrCl2+ | 29.2 | 8.9 | 3.7 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 23.8 |

| Cr3+ | – | – | 25.1 | 10.8 | 5.6 | – |

| Na+ | 14.4 | 7.6 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 14.1 |

| Mg2+ | – | 31.7 | 9.6 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 85.5 |

| Ni2+ | – | 36.3 | 10.3 | 6.3 | 4.0 | – |

Fig. 4.

Example chromatograph of the elution sequence of Cr(III)-species (CrCl2+, CrCl2+/CrCl30), as well as Na+, Mg2+ and Ni2+ in 1 M HNO3 from an AG50w-x8 cation column (120 × 3.2 mm ID). Shown are the gaussian fitting curves to individual elution peaks used for determining the volume of elutant required to elute the peak maximum for each species.

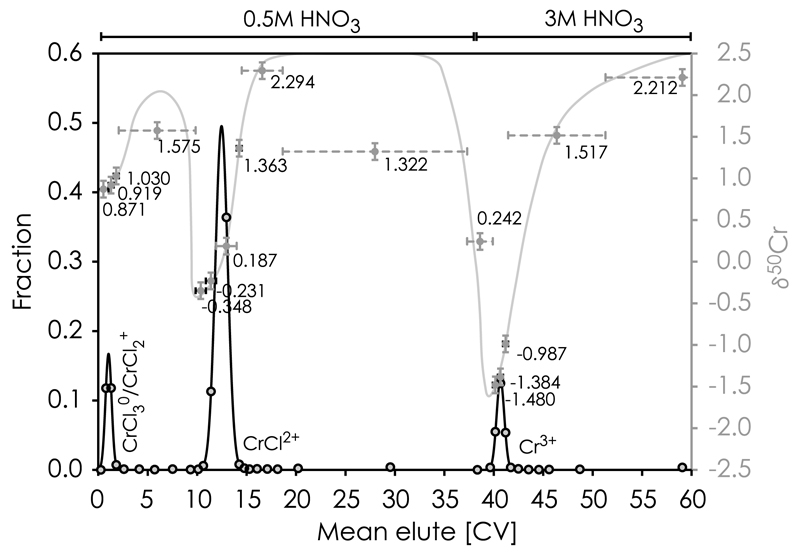

4. Inter-species and intra-peak Cr isotope fractionation

The complex behavior of Cr speciation and its isotopic fractionation during chromatographic purification is a direct consequence of 1) variable chemical abundances of multiple Cr-species in solution prior to column loading and differences in their relative selectivity for the ion exchanger, and 2) inter-species equilibrium isotope fractionation amongst these Cr-species combined with intra-peak Cr isotope fractionation through chromatographic elution. In order to investigate these isotope effects, we measured the Cr isotope composition of individual elution aliquots of a pure Cr standard, which was passed through a high-resolution chromatographic column. To ensure the presence of all Cr(III)-species in measurable amounts, we used the equilibrated 6 M HCl Cr stock solution.

4.1. Cr isotope fractionation between Cr(III) species

The partitioning of Cr isotopes between Cr(III)-species in solution was evaluated by measuring the Cr isotope composition of each elution peak and the magnitude of isotope fractionation between Cr(III)-species was calculated from:

| (8) |

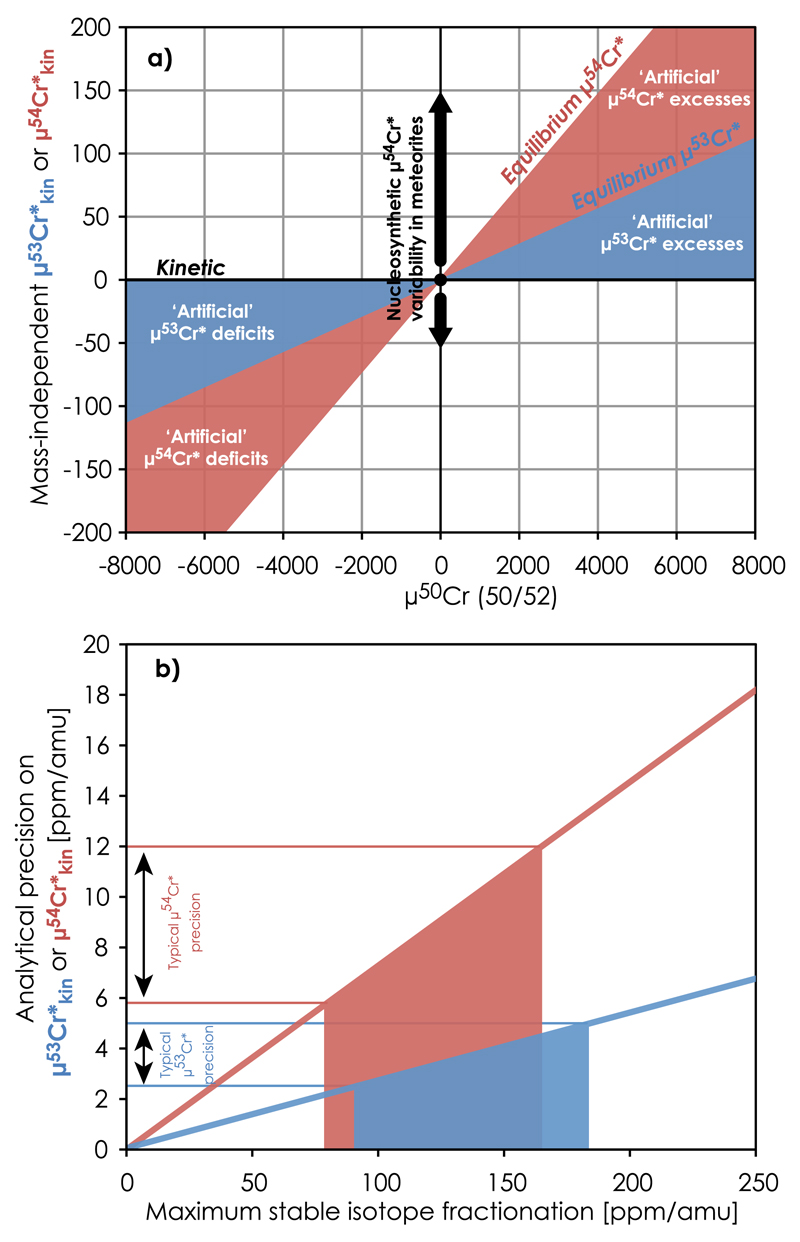

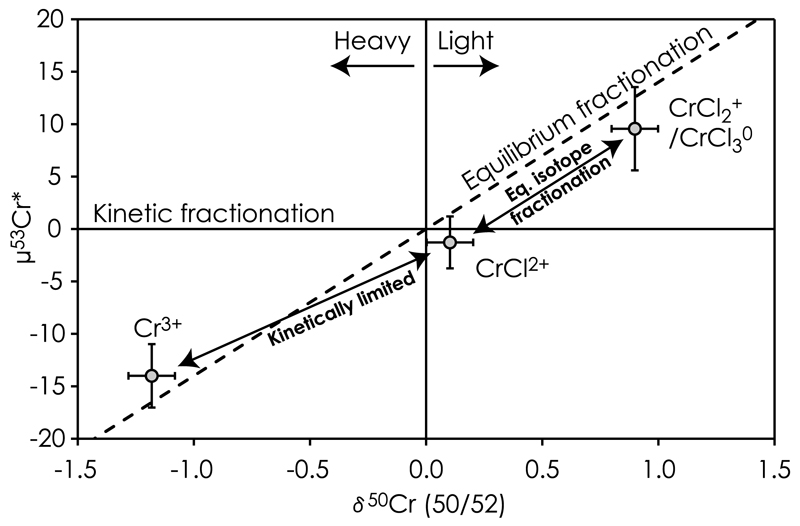

where superscript xx refers to the Cr isotope composition of a given Cr(III)-species, p or q. Our results show that with a δ50Cr value of −1.181 ± 0.035‰ (2se), the Cr3+ specie has the heaviest isotope composition, i.e. much heavier than the Cr-Cl2+ and CrCl2+/CrCl3° species with δ50Cr of 0.103 ± 0.013‰ and 0.899 ± 0.019‰, respectively (Table 3). Hence, Δ50Cr[Cr3+ − CrCl2+] = −1.284±0.037‰ (2se), Δ50Cr[CrCl2+ − CrCl2+/CrCl30] = −0.796 ±0.023‰ and Δ50Cr[Cr3+ − CrCl2+/CrCl3°] = −2.080 ± 0.039‰. This is qualitatively consistent with theoretical predictions; the strong and short Cr-ligand bonds in Cr(H2O)3+ preferentially partitions the heavier isotopes, while the longer and weaker Cr-ligand bonds in chlorinated Cr-complexes e.g. CrCl63− favour the lighter isotopes [18]. In such models, the magnitude of Cr isotope fractionation between Cr(H2O)3+ and CrCl63− is 3–4‰/amu at room temperature. Thus, the smaller (~1‰/amu) fractionation that we observe between Cr3+ and CrCl2+/CrCl30 with lower ligand number than CrCl63− is reasonably consistent with such models. This fractionation is of much smaller magnitude than the typical 3–6‰/amu room temperature Cr isotope fractionation observed between the heavy Cr(VI) and light Cr(III) redox pairs (e.g. [12,41,42]). These results emphasize the magnitude of artificial isotope fractionation resulting from incomplete Cr recovery during the oxidative Cr-chemistries that are commonly used in anion-exchange purification protocols (Table 1). Hence, excluding Cr(VI) from the purification procedure significantly reduces the risk of imposing artificial Cr isotope fractionation in the collected sample aliquots.Mass-dependent isotope fractionations induced through chromatography separation can result in apparent mass-independent artifacts that depend on the (in) validity of the applied mass fractionation correction (e.g. [26]). We note that for every 100ppm/amu of mass-dependent fractionation (50Cr/52Cr), 2.8 and 7.3 ppm artificial mass-independent anomaly in the mass-bias corrected μ53Cr* and μ54Cr*, respectively, can be generated (Fig. 6). Hence, a 1‰/amu purely equilibrium isotope fractionation between Cr(III) species generates 73 ppm μ54Cr* artificial anomaly when applying the commonly used kinetic mass-fractionation law, i.e. similar to the 68 ppm observed between Cr3+ and CrCl2+/CrCl3° for the partially equilibrated 6 M HCl Cr standard solution (Table 3). This corresponds to about 30% of the reported range of nucleosynthetic μ54Cr* anomalies in primitive meteorites [5,43] and is >10 times larger than the reported external precision of ~6 ppm for modern mass spectrometric techniques [23]. The limited stable isotope variability (<200 ppm/amu; [23]) reported for these meteorites can only account for up to 15 ppm μ54Cr* variability and therefore emphasizes the nucleosynthetic origin of the majority of reported meteoritic planetary-scale μ54Cr variability [5]. Smaller variations in meteorite components may, however, be significantly overprinted by artificial mass-independent effects from stable isotope fractionations, e.g. induced through chemical purification procedures.

Table 3.

Chromium isotope compositions of chromatographic elution aliquots, representing Cr(III)-species (Cr3+, CrCl2+, CrCl2+/CrCl30) eluting from a cation AG50w-x8 exchanger. Peak 1 represents CrCl2+/CrCl30, peak 2, CrCl2+, and peak 3, Cr3+. Uncertainties are the 2se of the replicate analysis.

| Elution fraction | Cr fraction | δ50Cr (50/52) | 2se | μ53Cr* (kin) | 2se | μ54Cr* (kin) | 2se | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak 1 | ||||||||

| N1 | 0.118 | 0.871 | 0.021 | 6.2 | 4.5 | 28.8 | 10.8 | 2 |

| N2 | 0.118 | 0.919 | 0.017 | 12.7 | 3.1 | 34.6 | 10.8 | 2 |

| N3 | 0.007 | 1.030 | 0.018 | 14.6 | 6.6 | 31.1 | 14.0 | 1 |

| Interpeak 1+2 | ||||||||

| N4 | 0.004 | 1.575 | 0.065 | −9.9 | 12.0 | 72.4 | 17.0 | 1 |

| Peak 2 | ||||||||

| N5 | 0.007 | −0.348 | 0.031 | −2.7 | 5.1 | −22.1 | 13.0 | 1 |

| N6 | 0.113 | −0.231 | 0.018 | −2.9 | 2.6 | −9.0 | 11.0 | 3 |

| N7 | 0.364 | 0.187 | 0.009 | −0.9 | 2.3 | 6.8 | 8.1 | 3 |

| N8 | 0.008 | 1.363 | 0.039 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 16.8 | 12.0 | 1 |

| Interpeak 2+3 | ||||||||

| N9 | 0.007 | 2.294 | 0.031 | −9.8 | 6.0 | −12.6 | 11.0 | 1 |

| N10 | 0.006 | 1.322 | 0.033 | −10.3 | 8.6 | −14.1 | 19.0 | 1 |

| N11 | 0.004 | 0.242 | 0.032 | −3.7 | 9.6 | −23.9 | 21.0 | 1 |

| Peak 3 | ||||||||

| N12 | 0.055 | −1.480 | 0.037 | −12.0 | 2.4 | −38.0 | 16.0 | 3 |

| N13 | 0.125 | −1.384 | 0.023 | −20.9 | 2.7 | −47.3 | 5.1 | 3 |

| N14 | 0.054 | −0.987 | 0.028 | 0.4 | 3.9 | −9.0 | 15.0 | 3 |

| N15 | 0.007 | 1.517 | 0.120 | −24.8 | 3.7 | −40.3 | 9.5 | 1 |

| N16 | 0.004 | 2.212 | 0.034 | 1.5 | 5.0 | −51.9 | 15.0 | 1 |

| Mass balance | 0.013 | −1.9 | 0.2 | |||||

| Peak 1 mass balance | 0.243 | 0.899 | 0.019 | 9.6 | 4.0 | 31.7 | 10.9 | |

| Peak 2 mass balance | 0.492 | 0.103 | 0.013 | −1.3 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 9.0 | |

| Peak 3 mass balance | 0.244 | −1.181 | 0.035 | −14.0 | 3.0 | −36.6 | 11.2 |

Fig. 6.

(a) Chromium three-isotope diagram showing the artificial mass-independent μ54Cr* and μ53Cr* anomalies resulting from equilibrium mass-dependent isotope fractionation (e.g. induced through equilibrium isotope partitioning between Cr(III)-species), corrected using the commonly used kinetic fractionation law. This amounts to 7.3 and 2.8 ppm artificial μ54Cr* and μ53Cr* anomaly, respectively, for every 100ppm/amu equilibrium mass-dependent fractionation. (b) The typical analytical precision on μ54Cr* and μ53Cr* limits the magnitude of such mass-dependent stable isotope fractionation to less than 80–180ppm μ54Cr* is used to infer 54Cr nucleosynthetic variability in primitive meteorites, whereas μ53 Cr* excesses (if correlating with Mn/Cr) is a proxy for radiogenic53Cr ingrowth from short-lived 53Mn decay.

Most chromatographic purification protocols, which utilize a cation exchanger for Cr purification prior to isotope analysis, rely on efficient elution of Cr in the form of Cr(III)-Cl species (e.g. [15,44,45]). Such protocols typically result in 10–30% loss of Cr in the form of Cr3+ (Table 1). A mass balance calculation shows that, for the partially equilibrated inter-species Cr(III) isotope fractionation observed for the 6 M HCl Cr standard solution (Table 3), preferential collection of ~75% of the total Cr in the form of Cr(III)-Cl species(peak1 and 2; i.e.CrCl2+ and CrCl2+) results in 185 ppm/amu lighter stable Cr isotope composition in the collected aliquot as compared to the true composition of the sample. This is a factor of about 4 times larger than the analytical uncertainty achievable by modern high-precision Cr isotope analysis using MC-ICP-MS on unspiked samples [23]. Furthermore, the magnitude of stable Cr isotope fractionation in the collected Cr aliquot corresponds to 5.2 and 13.5 ppm artificial excess μ53Cr* and μ54Cr*, respectively, i.e. outside the external reproducibility typically reported for Cr isotope analysis using MC-ICP-MS or TIMS (Fig. 6). These results stress the importance of high recovery gain through ion chromatographic purification of Cr.

The absolute magnitude of isotope fractionation between Cr(III)-species in the chromatographic solutions depends on the relative abundances of each species in the starting composition promoted through chemical sample pre-treatment. For example, the Cr isotope composition presented in Table 3 for the partially equilibrated 6 M HCl solution predominantly reflects the near equilibrium partitioning of Cr isotopes between Cr3+ (25%), CrCl2+ (50%) and CrCl2+/CrCl3° (25%), but also seems to preserve a memory of the earlier predominance of CrCl2+/CrCl30 promoted through the hot ( > 120 °C) 6 M HCl sample pre-treatment procedure (Fig. 3). Hence, the isotope composition of each Cr(III)-specie changes with variation in their relative abundance, as well as through chemical equilibration, which is known to be extremely slow for Cr(III)-Cl complexation at room temperature [34,35].

While isotopic fractionation of other transition metals such as Fe, Cu and Zn (e.g. [46]) are generally known to attain equilibrium fast and as such are controlled by equilibrium fractionation, the extremely slow reaction kinetics of Cr redox reactions and Cr(III)-Cl complexation at ambient conditions likely invokes kinetic isotope effects [47]. Fig. 7 shows that the measured Cr isotope composition of individual Cr(III)-species are only slightly different from that expected by pure equilibrium fractionation, but clearly resolved from pure kinetic fractionation. This implies that the 6 M HCl stock solution had reached a near-equilibrium composition after storage at room temperature for several months. We suggest that the apparently small deficiencies in μ53Cr* for CrCl2+ and CrCl2+/CrCl3° relative to pure equilibrium fractionation and their offset relative to Cr3+ (Fig. 7) may result from the slow reaction kinetics associated with de-chlorination of Cr(III)-Cl complexes and the partitioning of Cr isotopes between the three species. This is probably because the pair of species with the slowest reaction rate should kinetically limit isotope partitioning between more than one set of species. The similar deficit μ53Cr* observed for CrCl2+ and CrCl2+/CrCl3° species relative to an equilibrium fractionation trend therefore suggest that Cr isotope partitioning amongst these Cr(III)-species has approached an equilibrium composition. The slightly elevated μ53Cr* of Cr3+ as compared to the same equilibrium fractionation trend, on the other hand, suggests that isotope exchange between Cr3+ and CrCl2+ are kinetically limited by the sluggish reaction kinetics between these two species as follows,

| (9) |

Fig. 7.

Chromium isotope diagram showing the artificially produced mass-independent μ53Cr* anomalies for Cr(III)-species when using the exponential/kinetic fractionation law for mass-bias correction. The speciation assemblage was produced through partial equilibration of a pure CPI Cr standard by several months of exposure to 6 M HCl at room temperature. The exchange of Cr isotopes between Cr(III)-species has reached near equilibrium fractionation with the lighter isotopes partitioning for Cr(III)-Cl complexes with weak Cr-ligand bonds as opposed to the heavier isotopes, which prefer the Cr3+ specie. Isotope exchange between Cr3+ and CrCl2+ seems to be kinetically limited by the slow reaction kinetics of CrCl2+ de-chlorination. This effect may explain the apparently decreased in magnitude of artificial μ53Cr* anomaly relative to pure equilibrium isotope fractionation for all Cr(III)-species. Preferential loss of either one of these species can result in apparent anomalies in the mass-independent μ53Cr* and μ54Cr* components used to infer radiogenic and nucleosynthetic variability in primitive meteorites.

This interpretation is consistent with experimental studies [35] showing a slow change in Cr(III) speciation with storage time in dilute HCl after exposure to concentrated HCl solutions and demonstrating a pileup of the di-valent CrCl2+ species with progressive equilibration. This is expected if breaking of the last Cr(III)-Cl bond is the rate-limiting step towards formation of Cr3+. Progressive de-chlorination of Cr(III)-Cl complexes with decreasing temperature and HCl concentration is also predicted from our chemical speciation modeling (Fig. 3). The kinetic effect associated with dechlorination of the last chloride ion may be associated with a higher energy required for bond-breaking of this Cr(III)-Cl bond. As equilibrium between the Cr(III)-species is approached, their isotope compositions are expected to progress towards a purely equilibrium isotope fractionation trend. Hence, depending on the extent of chemical equilibration combined with Cr recovery, such isotope fractionation effects may introduce artificial mass-independent anomalies in the mass-bias corrected μ53Cr* and μ54Cr* values used to infer radiogenic and nucleosynthetic anomalies in meteoritic materials.

4.2. Intra-peak Cr isotope fractionation

Mass-dependent differences in the KD values for isotopologes of a given Cr-specie which partition for the exchanger can be expressed as stable isotope fractionation between dissolved and resin bound forms. To first order, the isotopic composition for all eluted fractions, as calculated by mass balance, agree with that of the unprocessed standard, i.e. δ50Cr ~0.0, indicating full recovery of Cr from the column. Within each Cr elution peak, the first few Cr fractions passing through the column are systematically enriched in the heavy isotopes followed by increasingly lighter compositions (Table 3, Fig. 8). Thus, the heavy isotope fractions for each Cr species elute faster from the column than its isotopically lighter counterpart, indicating that the light isotopes partitions more strongly for the functional groups on the cation exchanger than the heavier isotopes, i.e. 52KD/53 KD > 1. This preferential partitioning of lighter isotopes for the resin has previously been observed for Cr [48], as well as other elements, such as Ca [49], Fe [50], Cu and Zn [46], and Mg [51]. Such behavior is consistent with theoretical models based on differences in the vibrational energies of the isotopic substances, in which the isotopically lighter forms are predicted to partition more strongly for the exchanger because of their lower vibrational energy [16–18]. The magnitude of the intra-peak Cr isotope fractionation also increases from peak 1 through peak 3, indicative of longer retention time and thus progressive sorting effects amongst Cr isotopes.

Fig. 8.

Chromatographic elution curves of Cr(III)-species (Cr3+, CrCl2+, CrCl2+/CrCl3°) from an AG50w-x8 cation exchanger in HNO3 acid expressed as column volumes (CV). The Cr isotope composition, δ50Cr, of elution aliquots shows that heavy Cr characterizes each peak front, whereas tails are represented by light Cr. The gray curve is a guide to the eye and shows the influence of peak tailing on Cr isotope fractionation between individual elution peaks. Some peak overlapping may explain intermediate δ50Cr between light tails and heavy fronts just before each elution peak. Horizontal error bars (gray dotted lines) indicate the range of CVs collected in each cut, whereas vertical error bars (gray solid lines) show the estimated external analytical uncertainty (2sd ~ 100 ppm) of these measurements.

5. Strategies for efficient chromatographic separation and high recovery of Cr from a cation exchanger

As demonstrated in previous sections of this paper, the complexities associated with highly variable Cr speciation in acidic media (Fig. 3) coupled with significant inter-species mass-dependent Cr isotope fractionation (Fig. 7) may hamper an accurate determination of a sample’s Cr isotope composition using modern high-precision mass-spectrometric techniques. This is particularly pronounced if large amounts of Cr are lost through chromatographic purification. Hence, in an attempt to limit these complexities associated with insufficient Cr recovery (Table 1), we here evaluate the typical speciation of Cr prior to column loading for conventional purification protocols and further explore effective strategies to control Cr speciation in acidic media in an attempt to significantly and reproducibly increase its chromatographic recovery.

Numerous studies have reported complicated elution characteristics of Cr on cationic exchangers (e.g. [1,6,14,15,52]). These chemical protocols typically result in partial recoveries in the range of 70–90% (Table 1). Recovery of Cr in the form of Cr(III)-Cl complexes from a cation exchanger is commonly promoted by pre-column exposure of the sample matrix to HCl acid, typically through a hot 6 M HCl pre-treatment followed by cooling and dilution at room temperature. Our PHREEQC equilibrium speciation model (Fig. 3a) shows that at near room temperature more than one Cr species (Cr3+, CrCl2+, CrCl2+) are present over a wide range of HCl concentrations, including 6 M HCl. More importantly, the Cr3+ specie increases in abundance with decreasing temperature and HCl concentration. Given the widely differing distribution coefficients of these species for the cation exchanger (Table 2; Fig. 5), incomplete Cr recovery is therefore most likely associated with partial equilibration of the Cr speciation assemblage at room temperature prior to column loading. Hence, the presence of multiple of these species in experimental solutions precludes an efficient and reproducible separation of Cr from the sample matrix. A reliable strategy for obtaining a high Cr recovery from cation exchangers therefore relies on effective suppression of one or more Cr(III)-species in the loading acid. This can be done by carefully controlling acid molarity, temperature and equilibration time. Hence, while the extremely sluggish reaction kinetics of Cr complexation in acidic media is in general a complicating factor for efficient chromatographic separation, equilibration timescales that are longer than typical elution timescales can also be turned into an advantage.

Fig. 5.

Distribution coefficients, KD, of Cr[III]-species (Cr3+, CrCl2+, CrCl2+/CrCl3°), as well as Na+, Mg2+ and Ni2+ for an AG50w-x8 cation exchanger in HNO3 (0.5 M, 1 M, 2 M, 3 M, 4 M) and HCl (0.5 M) solutions.

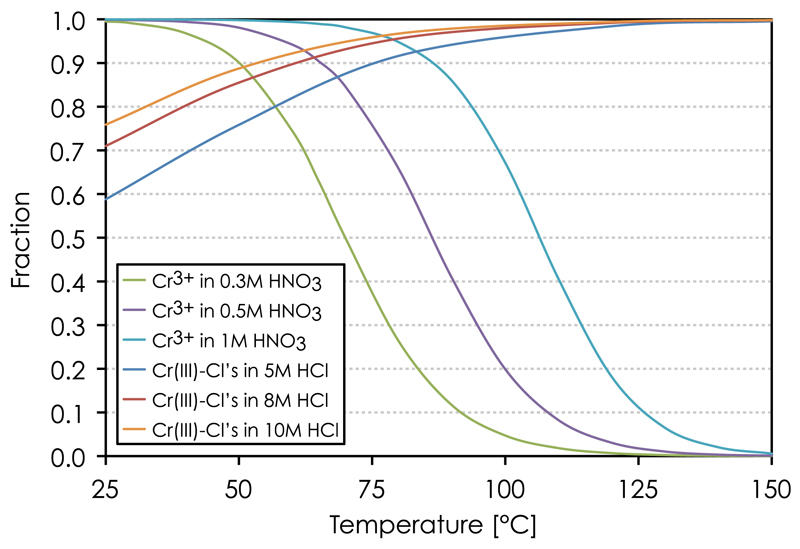

Inspection of Fig. 3 yields two plausible Cr(III) speciation assemblages with significant predominance of one or two of the Cr(III) species, which may be exploited for obtaining a high Cr recovery by elution through cation chromatographic columns. The first one involves a chemical sample pre-treatment procedure in which predominance of the Cr3+ species is promoted by exposure to HNO3 acid (>0.2 M) at about room temperature (Fig. 3a). This approach pushes the Cr speciation assemblage towards a high selectivity for the cation exchanger (Table 2) and may eficiently separate Cr from matrix elements with lower selectivities, such as Na. The second chemical pre-treatment strategy involves effective chlorination of Cr to form Cr(III)-Cl complexes with a low selectivity for the cation exchanger (Table 2) and thus makes it possible to separate Cr from matrix elements, such as Mg and Ni (Fig. 5). Such effective Cr-chlorination is promoted by exposing the sample matrix to concentrated HCl solutions (>8 M) at >100°C (Fig. 3i–j). In either case, an effective chromatographic elution strategy requires that the sample be loaded in dilute acid where the relative differences in distribution coeficients on a cation exchanger are generally large (Fig. 5), thereby providing suficient resolution for elemental separations. The chemical pre-treatment strategies therefore rely on the extremely slow reaction kinetics of Cr speciation in dilute acid at low temperature.

5.1. Dilute HNO3–H2O2 pre-treatment experiments

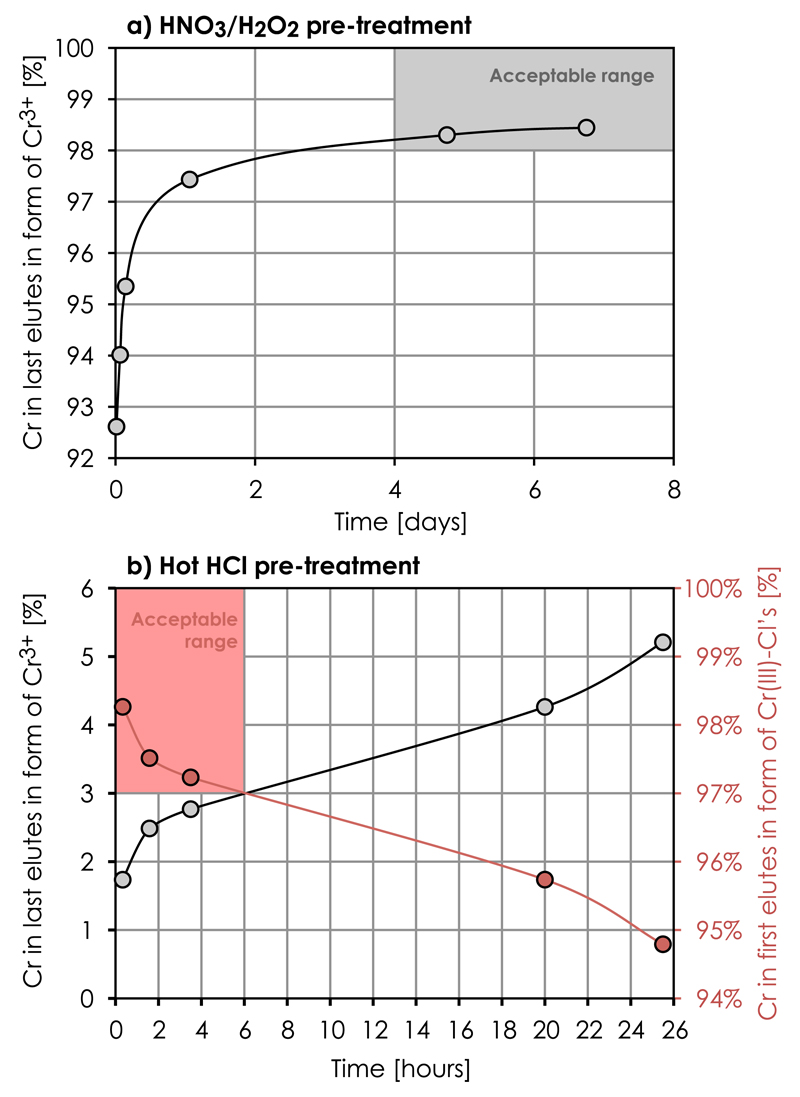

To ensure the presence of several Cr(III)-species in experimental solutions prior to testing chemical pre-treatment procedures, we used digestion aliquots of rock samples which had equilibrated for several days in room temperature 6 M HCl. Fig. 9 shows that near-complete transformation of Cr into its Cr3+ form can be expected from equilibration of Cr samples in even dilute HNO3 at about room temperature, which is convenient for storage prior to sample loading. lnitial chemical pre-treatment experiments showed that adding H2O2 (which acts as a reducing agent at low pH) to HNO3-digested sample solutions effectively aids in promotion of the Cr3+ species. Thus, we examined a chemical pre-treatment procedure on pure Cr standard solutions involving dissolution in 125 μl of 2 M HNO3 at ~100°C for 2 h followed by dilution in MilliQ H2O and addition of H2O2 to give a total volume of 0.5 ml of 0.5 M HNO3 + 3 wt% H2O2. The dissolved samples were subsequently stored at room temperature to approach an equilibrium composition and individual aliquots loaded on a cation column at discrete time intervals. A chromatographic separation of Cr3+ from Cr(III)-Cl species was performed using the KD values presented in Table 2. Fig. 10a shows the concentration of Cr3+ in the reaction vessels as a function of equilibration time, confirming the transformation of >98% Cr into its Cr3+ form after 4 days of equilibration at room temperature.

Fig. 9.

PHREEQC Cr speciation model showing the predominance of the Cr3+ specie in dilute HNO3 and Cr(III)-Cl complexes in 5–10 M HCl as a function of temperature.

Fig. 10.

Results of chemical Cr pre-treatment experiments; (a) Cr3+ formation in 0.5 M HNO3 and 3 wt% H2O2 as a function of time, and (b) formation of Cr(III)-Cl complexes at the expense of Cr3+ in hot (140°C) 10M HCl followed by immediate dilution with cold (5 °C) Milli-Q water to 0.5 M HCl and equilibration at room temperature as a function of time. Cr3+ and Cr(III)-Cl complexes were separated on an AG50w-x8 cation column according to the their distribution coefficients, KD (Table 2).

This pre-treatment procedure was further tested on sample matrices with various elemental abundances, which were allowed to equilibrate for 5 days at room temperature in 0.5 M HNO3 and 3 wt% H2O2. Table 4 shows that >98% Cr recovery (in the form of Cr3+) is achieved on most types of sample matrices tested and independent of the total amount of sample load up to 5 mg. However, HNO3–H2O2 pre-treatment of the USGS Bir-1 (basalt) and DNC-2 (dolerite) standards results in lower recoveries of ~90%. Given the much higher abundance of Fe relative to Cr and the low total Cr abundance in these sample compared to all other sample matrices tested, the poorer recovery may in part result from Fe interference on the redox capacity of H2O2. ln order to test this, we removed Fe from these sample matrices prior to the HNO3–H2O2 pre-treatment procedure using an anion exchange separation protocol in 6 M HCl as described in Bizzarro et al. [26]. Using this procedure, Cr has no preference for the anion exchanger in 6 M HCl and passes through together with the residual matrix elements. The chemical HNO3–H2O2 pre-treatment procedure was repeated on these Fe-cleaned samples, resulting in > ~ 97% Cr recovery for the Bir-1 and DNC-2 standards at 5 mg load (Table 4). On the other hand, this Fe-clean up step did not increase the Cr recovery for the 100 μg load tests, which may be related to the very small amount of Cr (30–40 ng) in these samples.

Table 4.

Results of sample pre-treatment experiments on various types of sample matrices.

| Sample | Type of sample | sample mass [mg] | Amount of Cr in sample [μg] | fraction Cr3+ | Mass fraction of Cr-Cl species | Recovery of Cr [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DiluteHNO3/H2O2 pre-treatmenta | ||||||

| N-1A-#8 | Hibonite-rich Ca-Al-rich inclusion (CAI) | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.994 | 0.006 | 99.4% |

| Y-#1 | Hibonite-rich Ca-Al-rich inclusion (CAI) | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.992 | 0.008 | 99.2% |

| 22E | Fine-grained Ca-Al-rich inclusion (CAI) | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.997 | 0.003 | 99.7% |

| N-53 | Melilite-rich type B/C Ca-Al-rich inclusion (CAI) | 1.70 | 1.29 | 0.998 | 0.002 | 99.8% |

| KT-1 | Melilite-rich FUN Ca-Al-rich inclusion (CAI) | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.996 | 0.004 | 99.6% |

| NWA 7686 | Ureilite | 1.20 | 6.18 | 0.998 | 0.002 | 99.8% |

| NWA 6043 | CR carbonaceous chondrite | 2.00 | 7.10 | 0.995 | 0.005 | 99.5% |

| NWA 5958 | Ung. carbonaceous chondrite | 2.00 | 7.00 | 0.990 | 0.010 | 99.0% |

| Allende | CV carbonaceous chondrite | 1.65 | 5.83 | 0.994 | 0.006 | 99.4% |

| Alfianello | L ordinary chondrite | 2.50 | 9.16 | 0.981 | 0.019 | 98.1% |

| CPI Cr | CPI International pure Cr standard | 0.01 | 10.00 | 0.983 | 0.017 | 98.3% |

| DTS-2b | Dunite, USGS standard | 5.00 | 77.50 | 0.983 | 0.017 | 98.3% |

| DTS-2b | Dunite, USGS standard | 0.10 | 1.55 | 0.988 | 0.012 | 98.8% |

| Bir-1a | Basalt, USGS standard | 5.00 | 1.85 | 0.887 | 0.113 | 88.7% |

| Bir-1ac | Basalt, USGS standard (purified for Fe) | 5.00 | 1.85 | 0.996 | 0.004 | 99.6% |

| Bir-1a | Basalt, USGS standard | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.941 | 0.059 | 94.1% |

| Bir-1ac | Basalt, USGS standard (purified for Fe) | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.890 | 0.109 | 89.1% |

| DNC-1a | Dolerite, USGS standard | 5.00 | 1.35 | 0.928 | 0.072 | 92.8% |

| DNC-1ac | Dolerite, USGS standard (purified for Fe) | 5.00 | 1.35 | 0.970 | 0.030 | 97.0% |

| DNC-1a | Dolerite, USGS standard | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.921 | 0.079 | 92.1% |

| DNC-1ac | Dolerite, USGS standard (purified for Fe) | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.912 | 0.088 | 91.2% |

| Concentrated hot HCl pre-treatmentb | ||||||

| Bir-1a | Basalt, USGS standard | 5.00 | 1.85 | 0.015 | 0.985 | 98.5% |

| Bir-1a | Basalt, USGS standard | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.003 | 0.997 | 99.7% |

| DTS-2b | Dunite, USGS standard | 5.00 | 77.50 | 0.023 | 0.977 | 97.7% |

| DTS-2b | Dunite, USGS standard | 1.00 | 15.50 | 0.011 | 0.989 | 98.9% |

| DTS-2b | Dunite, USGS standard | 0.10 | 1.55 | 0.015 | 0.985 | 98.5% |

| DNC-1a | Dolerite, USGS standard | 5.00 | 1.35 | 0.007 | 0.993 | 99.3% |

| DNC-1a | Dolerite, USGS standard | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.014 | 0.986 | 98.6% |

| CPI Cr | CPI International pure Cr standard | 0.10 | 100.00 | 0.006 | 0.994 | 99.4% |

| CPI Cr | CPI International pure Cr standard | 0.01 | 10.00 | 0.017 | 0.983 | 98.3% |

Sample dissolution in 125 μl of 2 M HNO3 at ~100°C for 2 h followed by dilution in MilliQ H2O and addition of 3 wt% H2O2 to give a total volume of 0.5 ml of 0.5 M HNO3 +3 wt% H2O2. This aliquot was subsequently stored at room temperature for 5 days prior to column loading.

Sample dissolution in 250 μl of 10 M HCl at 140 °C for >18 h followed by dilution to a total volume of 5 ml of 0.5 M HCl using cold (5°C) MilliQ H2O immediately prior to column loading.

Fe was removed from the sample matrix by means of an anion exchange procedure in 6 M HCl according to Bizzarro et al. [26], in which Cr (III) has no preference for the exchanger.

5.2. Concentrated hot HCl pre-treatment experiments

The promotion of Cr(III)-Cl complex formation is, on the other hand, best achieved through Cr equilibration in concentrated HCl at > ~100°C (Fig. 9). Thus, we tested a chemical pre-treatment procedure on a pure Cr standard solution involving dissolution in 250 μl of 10 M HCl at >120 °C followed by immediate dilution to a total volume of 5 ml of 0.5 M HCl using cold (5 °C) MilliQ water. The rapid decrease in temperature following this procedure lowers the reaction rates and thereby quenches retrograde de-chlorination of Cr(III)-Cl complexes that would otherwise occur at intermediate temperatures. This procedure preserves a higher fraction of Cr species with low selectivities for the cation exchanger. The sample aliquots were subsequently loaded on the cation columns at discrete time intervals after dilution and Cr3+ and Cr(III)-Cl species were separated according to their KD values (Table 2). Fig. 10b shows a rapid decline in the abundance of Cr(III)-Cl species within the first two hours of dilution and storage at room temperature, suggesting transformation of ~2.5% Cr(III)-Cl complexes into Cr3+. This is consistent with the chemical speciation model showing that exposure to dilute HCl results in slow hydration and de-chlorination of Cr(III)-Cl complexes, eventually favoring production of the trivalent Cr3+ species (Fig. 3 and [35]). This underscores the importance of retarding the reaction kinetics of the de-chlorination process by a rapid temperature decrease in dilute HCl after the hot 10 M HCl pre-treatment. Using this procedure, more than 97% recovery in the form of Cr(III)-Cl complexes from the cation exchanger can be expected when loading and eluting Cr from the column within ~6h of dilution (Fig. 10b). This is quantitatively consistent with the results of Pezzin et al. [35]. As indicated by the observed Cr isotope fractionation between Cr3+ and Cr(III)-Cl species (Fig. 7), the kinetics of these reactions are mostly limited by CrCl2+ transformation to Cr3+ and the de-chlorination of the last Cr(III)-Cl bond therefore represents a bottleneck in efficient Cr3+ production. Hence, the kinetic limitations of this process are exploited in the HCl pre-treatment procedure.

This HCl pre-treatment procedure was further tested on sample matrices with various elemental abundances, which were allowed to equilibrate in hot (>120 °C) 10 M HCl for >18 h and subsequently diluted with cold MilliQ water to 0.5 M HCl immediately prior to column loading. The results show that >97.5% recovery (in the form of Cr(III)-Cl’s) is achieved on all types of sample matrices reported in Table 4, demonstrating the reproducibility of this approach.

Taking control of the complex speciation behavior of Cr, it is important to be aware that the hot HCl sample pre-treatment procedure generates a distillate and residue in the closed reaction vessel. This binary HCl-water mixture results in a negative azeotrope, meaning that the sample residue approach the azeotropic HCl concentration at 6.6 M HCl through distillation, whereas the distillate diverges from the azeotrope HCl concentration. Accordingly, the HCl concentration decreases from 10 M towards 6.6 M through progressive distillation and Cr in the sample residue approaches an equilibrium speciation at the azeotropic composition. Fig. 9 shows that such decline in HCl molarity does not drastically change the Cr speciation at high temperature, but may be hampered by ensuring a high liquid to gas volume ratio in the reaction vessel. We used a dissolution volume of 250 μl 10 M HCl in a 7 ml PFA reaction vessel, which prevented >50% of the solution from evaporating onto the beaker walls.

Given the highly contrasting distribution coefficients of Cr3+ and Cr(III)-Cl species on a cation exchanger, the chemical sample pre-treatment strategies proposed here may be favorably exploited when separating Cr from either elements with low cation selectivity, such as alkali metals, or those with higher selectivity, such as Mg and Ni. Hence, a chromatographic elution procedure may give very different elution characteristics of Cr when combined with either a HNO3 or HCl pre-treatment procedure. A high-purity Cr fraction can therefore be obtained by passing a sample over the same cation column twice using the two different chemical sample pre-treatment strategies. This allows for Cr recoveries of >95%, at which level the magnitude of mass-dependent Cr isotope fractionation can be considered negligible compared to the reproducibility of Cr isotope measurements using modern high-precision mass spectrometric techniques.

6. Conclusions

Using cation chromatographic separation procedures, the distribution coefficients of individual Cr(III) species in HCl and HNO3 acid media was calculated and the magnitude of Cr isotope fractionation between them measured by MC-ICP-MS. Our results demonstrate the highly contrasting elution characteristics of Cr(III) species (Cr3+, CrCl2+, CrCl2+, CrCl3°). The magnitude of stable isotope fractionation between each species further emphasizes the importance of high Cr recovery during chromatographic purification for accurate isotope analysis. Such high recoveries are rarely attained using conventional cation chromatographic separation protocols for Cr. Thus, in order to evaluate plausible strategies for a high Cr recovery, we determined the speciation of Cr in HCl and HNO3 solutions by equilibrium speciation modeling and experimental sample pre-treatment procedures combined with chromatographic elution tests. This analysis shows that reproducible recoveries in excess of 97% for various sample matrices can be obtained through either 1) effectively promoting formation of the tri-valent Cr3+ specie by >5 days exposure to 0.5 M HNO3 and 3 wt% H2O2 solutions at room temperature prior to column loading or 2) formation of Cr(III)-Cl complexes by several hours of exposure to concentrated HCl at elevated temperature (>120°C) and subsequent dilution immediately prior to column loading. The HNO3/H2O2 sample pre-treatment strategy uses a cationic chromatographic retention strategy through which other matrix elements with selectivities lower than Cr3+ (such as Na and K) can effectively be separated from Cr. The HCl sample pre-treatment strategy, on the other hand, uses a cationic chromatographic elution strategy that takes advantage of the sluggish reaction kinetics of de-chlorination of Cr at room temperature, thereby effectively eluting Cr from the column in the form of Cr(III)-Cl complexes. This procedure can be used for separating Cr from matrix elements with higher selectivities for the exchanger (such as Mg and Ni) than the Cr(III)-Cl species. A high-purity Cr fraction for high-precision isotope analysis can be obtained through a two-pass cationic chromatographic strategy by utilizing both chemical pre-treatment procedures, thereby obtaining total Cr recoveries in excess of 95%. The consistent high Cr recoveries ensured by our protocol are required for studies necessitating an accurate determination of both the mass-dependent and mass-independent Cr isotope compositions without addition of an isotopically-enriched spike, which is key for the investigation of rare to irreplaceable meteoritic materials.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by grants from the Danish National Research Foundation (grant number DNRF97) and from the European Research Council (ERC Consolidator grant agreement 616027-STARDUST2ASTEROIDS) to M.B.

References

- [1].Moynier F, Yin QZ, Schauble E. Isotopic evidence of Cr partitioning into earth’s core. Science. 2011;331:1417–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.1199597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Frei R, Gaucher C, Poulton SW, Canfield DE. Fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric oxygenation recorded by chromium isotopes. Nature. 2009;461:250–253. doi: 10.1038/nature08266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Frei R, Gaucher C, Døssing LN, Sial AN. Chromium isotopes in carbonates — A tracer for climate change and for reconstructing the redox state of ancient seawater, Earth Planet. Sci Lett. 2011;312:114–125. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shukolyukov A, Lugmair GW. Isotopic evidence for the cretaceous-Tertiary impactor and its type. Science. 1998;282:927–930. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Trinquier A, Birck J-L, Allègre CJ. Widespread 54Cr heterogeneity in the inner solar system. Astrophys J. 2007;655:1179–1185. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Qin L, Alexander CMO, Carlson RW, Horan MF, Yokoyama T. Contributors to chromium isotope variation of meteorites. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2010;74:1122–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2009.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Warren PH. Stable-isotopic anomalies and the accretionary assemblage of the Earth and Mars: a subordinate role for carbonaceous chondrites. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys. 2011;311:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.08.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dauphas N, Remusat L, Chen JH, Roskosz M, Papanastassiou DA, Stodolna J, et al. Neutron-rich chromium isotope anomalies in supernova nanoparticles. Astrophys J. 2010;720:1577–1591. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/720/1/1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Trinquier A, Elliott T, Ulfbeck D, Coath C, Krot AN, Bizzarro M. Origin of nucleosynthetic isotope heterogeneity in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science. 2009;324:374–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1168221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Collins KE, Bonato PS, Archundia C, de Queiroz MELR, Collins CH. Column chromatographic speciation of chromium for Cr(VI) and several species of Cr(III) Chromatographia. 1988;26:160–162. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ball JW, Bassett RL. Ion exchange separation of chromium from natural water matrix for stable isotope mass spectrometric analysis. Chem Geol. 2000;168:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ellis AS, Johnson TM, Bullen TD. Chromium isotopes and the fate of hexavalent chromium in the environment. Science. 2002;295:2060–2062. doi: 10.1126/science.1068368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Frei R, Rosing MT. Search for traces of the late heavy bombardment on earth—results from high precision chromium isotopes. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys. 2005;236:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2005.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Birck J-L, Allègre CJ. Manganese—chromium isotope systematics and the development of the early Solar System. Nature. 1988;331:579–584. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Trinquier A, Birck J-L, Allègre CJ. High-precision analysis of chromium isotopes in terrestrial and meteorite samples by thermal ionization mass spectrometry. J Anal At Spectrom. 2008;23:1565–1574. doi: 10.1039/b809755k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bigeleisen J, Mayer MG. Calculation of equilibrium constants for isotopic exchange reactions. J Chem Phys. 1947;15:261. doi: 10.1063/1.1746492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Urey HC. The thermodynamic properties of isotopic substances. J Chem Soc. 1947:562–581. doi: 10.1039/jr9470000562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schauble E, Rossman GR, Taylor HP., Jr Theoretical estimates of equilibrium chromium-isotope fractionations. Chem Geol. 2004;205:99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2003.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sikora ER, Johnson TM, Bullen TD. Microbial mass-dependent fractionation of chromium isotopes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2008;72:3631–3641. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.05.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Døssing LN, Dideriksen K, Stipp SLS, Frei R. Reduction of hexavalent chromium by ferrous iron: a process of chromium isotope fractionation and its relevance to natural environments. Chem Geol. 2011;285:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2011.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Han R, Qin L, Brown ST, Christensen JN, Beller HR. Differential isotopic fractionation during Cr(VI) reduction by an aquifer-Derived bacterium under aerobic versus denitrifying conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2462–2464. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07225-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Šillerová H, Chrastný V, Čadkova E, Komárek M. Isotope fractionation and spectroscopic analysis as an evidence of Cr(VI) reduction during biosorption. Chemosphere. 2014;95:402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schiller M, Van Kooten E, Holst JC, Olsen MB, Bizzarro M. Precise measurement of chromium isotopes by MC-ICPMS. J Anal At Spectrom. 2014;29:1406–1416. doi: 10.1039/c4ja00018h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schoenberg R, Zink S, Staubwasser M, von Blanckenburg F. The stable Cr isotope inventory of solid Earth reservoirs determined by double spike MC-ICP-MS. Chem Geol. 2008;249:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2008.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Farkaš J, Chrastný V, Novák M, Čadkova E, Pašava J, Chakrabarti R, et al. Chromium isotope variations (δ53/52Cr) in mantle-derived Cr sources and their products of oxidative weathering: implications for environmental studies and the evolution of δ53/52Cr in the Earthýs upper mantle over geologic time. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2013:123. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bizzarro M, Paton C, Larsen KK, Schiller M, Trinquier A, Ulfbeck D. High-precision Mg-isotope measurements of terrestrial and extraterrestrial material by HR-MC-ICPMS—implications for the relative and absolute Mg-isotope composition of the bulk silicate Earth. J Anal At Spectrom. 2011;26:565. doi: 10.1039/c0ja00190b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shukolyukov A, Lugmair G. Manganese–chromium isotope systematics of carbonaceous chondrites. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys. 2006;250:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2006.07.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kekesi T, Torok TI, Isshiki M. Anion exchange of chromium, molybdenum and tungsten species of various oxidation states, providing the basis for separation and purification in HCl solutions. Hydrometallurgy. 2005;77:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.hydromet.2004.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nelson F, Murase T, Kraus KA. Ion exchange procedures: i. Cation exchange in concentration HCl and HClO4 solutions. J Chromatogr A. 1964;13:503–535. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)95146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Paton C, Hellstrom J, Paul B, Woodhead J, Hergt J. Iolite Freeware for the visualisation and processing of mass spectrometric data. J Anal At Spectrom. 2011;26:2508–2518. doi: 10.1039/c1ja10172b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Parkhurst DL, Appelo C. US Geological Survey Techniques and Methods, Book 6, Modeling Techniques. 2013. Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3—a computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kinniburgh DG, Cooper DM. PhreePlot. Creating graphical output with PHREEQC. Users Manual. 2012:1–574. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Collins CH, Pezzin SH, Rivera JFL, Bonato PS, Windmöller CC, Archundia C, et al. Liquid chromatographic separation of aqueous species of Cr(VI) and Cr(III) J Chromatogr A. 1997;789:469–478. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bjerrum MJ, Bjerrum J. Estimation of small stability constants in aqueous solution. the chromium (III) chloride system. Acta Chem Scand. 1990;44:358–363. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pezzin SH, Archundia C, Collins KE, Collins CH. Product speciation and aquation after the reaction of 51Cr(VI) with concentrated HCl or H2SO4, Czech. J Phys. 2000;50:315–320. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Narusawa Y, Kanazawa M, Takahashi S, Morinaga K, Nakano K. Kinetics and mechanism of acid hydrolysis of trichlorotrithioureachromium (III) complex and chloride anation of trans-dichlorotetraquochromium (III) complex ion. J Inorg Nucl Chem. 1967;29:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-1902(67)80152-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Magini M. X-ray diffraction study of concentrated chromium (III) chloride solutions. I. Complex formation analysis in equilibrium conditions. J Chem Phys. 1980;73:2499–2505. doi: 10.1063/1.440361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Strelow F. An ion exchange selectivity scale of cations based on equilibrium distribution coefficients. Anal Chem. 1960;32:1185–1188. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mayer SW, Tompkins ER. Ion exchange as a separations method IV. a theoretical analysis of the column separations process1. J Am Chem Soc. 1947;69:2866–2874. doi: 10.1021/ja01203a069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Strelow F, Rethemeyer R, Bothma C. Ion exchange selectivity scales for cations in nitric acid and sulfuric acid media with a sulfonated polystyrene resin. Anal Chem. 1965;37:106–111. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zink S, Schoenberg R, Staubwasser M. Isotopic fractionation and reaction kinetics between Cr(III) and Cr(VI) in aqueous media. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2010;74:5729–5745. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang X, Johnson TM, Ellis AS. Equilibrium isotopic fractionation and isotopic exchange kinetics between Cr(III) and Cr(VI) Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2015;153:72–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Larsen KK, Trinquier A, Paton C, Schiller M, Wielandt D, Ivanova MA, et al. Evidence for magnesium isotope heterogeneity in the solar protoplanetary disk. Astrophys J. 2011;735:L37. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/735/2/L37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bonnand P, Parkinson IJ, James RH, Karjalainen A-M, Fehr MA. Accurate and precise determination of stable Cr isotope compositions in carbonates by double spike MC-ICP-MS. J Anal At Spectrom. 2011;26:528–535. doi: 10.1039/c0ja00167h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yamakawa A, Yamashita K, Makishima A, Nakamura E. Chemical separation and mass spectrometry of Cr, Fe, Ni, Zn, and Cu in terrestrial and extraterrestrial materials using thermal ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9787–9794. doi: 10.1021/ac901762a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Maréchal C, Albarède F. Ion-exchange fractionation of copper and zinc isotopes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2002;66:1499–1509. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Johnson TM, Bullen TD. Mass-dependent fractionation of selenium and chromium isotopes in low-temperature environments. Rev Mineral Geochem. 2004;55:289–317. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Fujii T, Moynier F, Yin Q-Z, Yamana H. Mass-independent isotope fractionation in the chemical exchange reaction of chromium (III) using a crown ether. J Nucl Sci Technol. 2008;6:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Russell WA, Papanastassiou DA. Calcium isotope fractionation in ion-exchange chromatography. Anal Chem. 1978;50:1151–1154. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Anbar AD, Roe JE, Barling J, Nealson KH. Nonbiological fractionation of iron isotopes. Science. 2000;288:126–128. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chang VTC, Makishima A, Belshaw NS, O’Nions RK. Purification of Mg from low-Mg biogenic carbonates for isotope ratio determination using multiple collector ICP-MS. J Anal At Spectrom. 2003;18:296–301. doi: 10.1039/b210977h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wilkins DH. The separation and determination of nickel chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium, tungsten, molybdenum, niobium and tantalum in a high temperature alloy by anion-exchange. Talanta. 1959;2:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lugmair GW, Shukolyukov A. Early solar system timescales according to 53Mn-53Cr systematics. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1998;62:2863–2886. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nyquist L, Lindstrom D, Mittlefehldt D, Shih CY, Wiesmann H, Wentworth S, et al. Manganese-chromium formation intervals for chondrules from the Bishunpur and Chainpur meteorites. Meteorit Planet Sci. 2001;36:1–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-5100.2001.tb01930.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kitchen JW, Johnson TM, Bullen TD, Zhu J. Chromium isotope fractionation factors for reduction of Cr(VI) by aqueous Fe(II) and organic molecules. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2012;89:190–201. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Jamieson-Hanes JH, Gibson BD. Chromium isotope fractionation during reduction of Cr(VI) under saturated flow conditions. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:6783–6789. doi: 10.1021/es2042383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Frei R, Polat A. Chromium isotope fractionation during oxidative weathering—implications from the study of a Paleoproterozoic (ca. 1.9 Ga) paleosol, Schreiber Beach Ontario, Canada. Precambrian Res. 2013;224:434–453. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Götz A, Heumann KG. Chromium trace determination in inorganic, organic and aqueous samples with isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 1988;331:123–128. doi: 10.1007/BF01105153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]