Abstract

Chondroitin sulfate (CS) is one of several glycosaminoglycans that are major components of proteoglycans. A linear polymer consisting of repeats of the disaccharide -4GlcAβ1-3GalNAcβ1-, CS undergoes differential sulfation resulting in five unique sulfation patterns. Because of the dimer repeat, the CS glycosidic “backbone” has two distinct sets of conformational degrees of freedom defined by pairs of dihedral angles: (ϕ1, ψ1) about the β1-3 glycosidic linkage and (ϕ2, ψ2) about the β1-4 glycosidic linkage. Differential sulfation and the possibility of cation binding, combined with the conformational flexibility and biological diversity of CS, complicate experimental efforts to understand CS three-dimensional structures at atomic resolution. Therefore, all-atom explicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulations with Adaptive Biasing Force sampling of the CS backbone were applied to obtain high resolution, high precision free energies of CS disaccharides as a function of all possible backbone geometries. All ten disaccharides (β1-3 vs. β1-4 linkage x five different sulfation patterns) were studied; additionally, ion effects were investigated by considering each disaccharide in the presence of either neutralizing sodium or calcium cations. GlcAβ1-3GalNAc disaccharides have a single, broad, thermodynamically important free-energy minimum whereas GalNAcβ1-4GlcA disaccharides have two such minima. Calcium cations but not sodium cations bind to the disaccharides, and binding is primarily to the GlcA –COO− moiety as opposed to sulfate groups. This binding alters the glycan backbone thermodynamics in instances where a calcium cation bound to –COO− can act to bridge and stabilize an interaction with an adjacent sulfate group, whereas, in the absence of this cation, the proximity of a sulfate group to –COO− results in two like charges being both desolvated and placed adjacent to each other and is found to be destabilizing. In addition to providing information on sulfation and cation effects, the present results can be applied to building models of CS polymers and as a point of comparison in studies of CS polymer backbone dynamics and thermodynamics.

Introduction

Chondroitin sulfate (CS) is one of several glycosaminoglycans that exist as covalent attachments to core proteins in proteoglycans. Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are linear polysaccharides that consist of repeating disaccharide units that include an amino sugar; hyaluronan, dermatan sulfate, keratan sulfate, heparin, and heparan sulfate are also classified as GAGs. CS is made up of repeating units of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine [(-4GlcAβ1-3GalNAcβ1-)n] that are variably sulfated,1-3 and CS chains can reach lengths anywhere between n = 40 to 100 disaccharide units.4 As an integral part of proteoglycans, CS forms a component of the extracellular matrix, and is well known for its structural role in cartilage.

GAGs, with the exception of hyaluronan, are covalently attached to Ser residues of core proteins in proteoglycans (PGs) via a tetrasaccharide linker: a xylose is first O-linked to Ser, followed by two galactose residues, and finally a glucuronic acid.5 Hyaluronan, on the other hand, interacts noncovalently with PGs with hyaluronan binding motifs.6 Xylosylation of PG core protein occurs in the ER and continues in the early Golgi, addition of galactose takes place in the Golgi, and the final sugar of the tetrasaccharide linker, GlcA, is added in the medial/trans Golgi. Upon completion of this linker region the alternating addition of GalNAc and GlcA to the non-reducing end continues in the Golgi to form the CS polymer.7

There are five distinct CS disaccharides that are produced by successive modification by separate sulfotransferases: the O unit [GlcA-GalNAc] is non-sulfated; the A unit [GlcA-GalNAc(4S)] is sulfated at the GalNAc 4 oxygen; the C unit [GlcA-GalNAc(6S)] is sulfated at the GalNAc 6 oxygen; the D unit [GlcA(2S)-GalNAc(6S)] is 2-O-sulfated on GlcA and 6-O-sulfated on GalNAc; and the E unit [GlcA-GalNAc(4S,6S)] is 4- and 6-O-sulfated on GalNAc (summarized in Supporting Information Table S1).8 The CS biosynthetic pathway is responsible for producing these CS disaccharides with their distinct sulfation patterns (sulfation sites are shown in Figure 1). The sulfation modifications occur during CS chain lengthening and are catalyzed by six known sulfotransferase enzymes that act along two different sulfation pathways as determined by an initial GlcNAc sulfation at either the 4- or 6-O position.8 Four sulfotransferases can modify the O unit to direct sulfation along one of the two pathways. For this first pathway, there are three chondroitin 4-O-sulfotransferases (C4ST-1, −2, and −3) whose action yields the singly sulfated A unit. The A unit may then be further sulfated at the GalNAc 6 position by GalNAc 4-sulfate 6-O-sulfotransterase (GalNAc4S-6ST) to yield the E unit. With regard to the second pathway, chondroitin 6-O sulfotransferase (C6ST-1) acts on the O unit to yield the singly sulfated C unit. Uronyl 2-O-sulfotransferase (UST) may then act on the uronic acid of the C unit to transform it into the D unit.

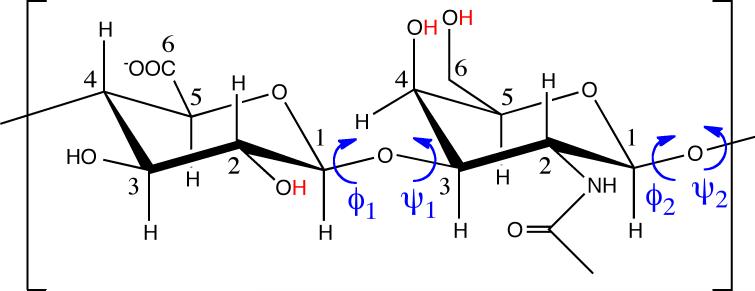

Figure 1.

The O disaccharide [(-4GlcAβ1-3GalNAcβ1-)] of CS. Red hydrogens on hydroxyl groups indicate potential sites for enzymatic sulfation (i.e. replacement of –H with –SO3−) and (ϕ1, ψ1) and (ϕ2, ψ2) are the two distinct degrees of CS backbone conformational freedom. Carbon atoms have been numbered.

The disaccharide units of CS can be characterized by their glycan backbones, that is, the monosaccharide components and the glycosidic linkages that join them. By this definition the O unit of CS has two distinct disaccharides: Disaccharide O1, GlcAβ1-3GalNAcβ; and Disaccharide O2, GalNAcβ1-4GlcAβ. The two respective glycosidic linkages can each be defined by a pair of dihedral angle values (ϕ, ψ). For O1, ϕ = Oring-1-Oglycosidic-3 and ψ = 1-Oglycosidic-3-4 (Figure 1, “(ϕ1, ψ1)”), and for O2, ϕ = Oring-1-Oglycosidic-4 and ψ = 1-Oglycosidic-4-5 (Figure 1, “(ϕ2, ψ2)”). These definitions also hold for the sulfated analogs of O1 (A1, C1, D1, and E1) and of O2 (A2, C2, D2, and E2), resulting in ten total unsulfated and variably sulfated disaccharide units that each contribute to the conformational properties of the CS backbone.

When CS is modified by sulfation it has two types of charged groups, carboxylate and sulfate, that can interact with cations and water to form a hydrated matrix. In the context of cartilage for example, this matrix resists compressive forces and contributes to healthy joint function.5 Ca2+ concentration is about four orders of magnitude greater in extracellular space than in cytoplasm, and the apparent association constant of CS for Ca2+ is approximately 14mM.9 Such binding is not unique to CS as Ca2+ binds to other GAG species, including hyaluronan, which notably contains no sulfate groups, but only carboxylate groups. Nonetheless, in CS both carboxylate and sulfate “sites” are occupied by calcium based on binding stoichiometry.10 And, since CS has been shown to have a Ca2+ binding affinity lower than heparin, which is highly sulfated, but greater than keratan sulfate or hyaluronan, which is unsulfated, charge density on the GAG polymer may be an important factor in cation binding.10 Data showing calcium binding to be a linear function of GAG concentration can be interpreted as Ca2+ ions not cross-bridging GAG chains adjacent to one another on a core protein,10 though this view is contradicted by other CS-calcium binding models.11 In addition to Ca2+, CS can bind monovalent cations such as Na+, though not as strongly.10 In the cartilage matrix, a variety of cations are present at differing concentrations. Potassium and calcium are preferred over sodium for incorporation into cartilage matrices, of which CS is one component.12

Previous experimental studies have produced atomic-resolution three dimensional structural information, including backbone conformations, for CS disaccharides and oligosaccharides that are modified by sulfation at various positions.13 These data come from X-ray crystallography of CS binding proteins in complexes with CS14-19 and of CS alone,20-21 as well as from solution NMR.22-23 These structural data have enabled computational studies of various forms of CS via molecular modeling techniques and molecular dynamics simulations. Early computational studies of sulfation effects of CS employed models that lacked water and counterions.24 But, increased access to computational power has allowed for explicit representation of solvent in more recent CS studies,25 which include the development of a CS “C unit” (sulfated at carbon 6 of GalNAc)-specific force field.26 A comparison of how different water models influence CS backbone conformation has even been performed, which highlighted the importance in striking a balance between accuracy of the model used and computational expense.27

To extend on these existing studies, the present work determines the conformational free energies as a function of (ϕ, ψ) (ΔG(ϕ, ψ)) for all 10 CS disaccharides described above using molecular dynamics simulations with modern all-atom explicit-solvent force field technology.28-31 In addition to considering all variable sulfation states, simulations are run with either Ca2+ or Na+ cations to determine cation binding effects on ΔG(ϕ, ψ). The Adaptive Biasing Force (ABF)32-33 methodology (as implemented in the NAMD software34) is used to facilitate sampling of (ϕ, ψ) space. Triplicate ABF simulations with small bin size and 200-ns sampling times yield high precision ΔG(ϕ, ψ) surfaces with coverage of the full extent of (ϕ, ψ) values, allowing for quantitative evaluation of sulfation- and cation-induced perturbations to free-energy minima and for determining the locations and heights of conformational transition states and free-energy maxima. These data can be applied to GAG polymer model building, and therefore proteoglycan molecular modeling, and are thus anticipated to be of utility in furthering proteoglycan structural biology, which presents significant experimental challenges due to GAG flexibility and microheterogeneity.

Methods

Systems were represented using the CHARMM C36 biomolecular force field for carbohydrates28-30 and the TIP3P water model.35-36 Molecular dynamics simulations were done with the NAMD program v. 2.9.34 The CHARMM program37-38 v. 37b1 was used for system construction and for post-simulation trajectory analysis, and molecular graphics were produced with the VMD program.39 After construction, systems were energy minimized for 5000 steps. This was followed by a 20,000 step heating stage and a 20,000-step equilibration stage. Both stages included harmonic positional restraints on carbohydrate non-hydrogen atoms. The heating stage employed a 0.0005 ps timestep and no bond constraints while the equilibration stage used a 0.002 ps timestep with bonds to hydrogen atoms and water molecule geometries constrained40 to values defined by force field equilibrium length and angle values. Langevin thermostating41 and Langevin piston barostating42 were used to maintain temperature at 310 K and pressure at 1 atm, and the BBK method43 was used to integrate the equations of motion. Nonbonded interactions were truncated using a spherical atom-based cutoff at 10 Å, with an energy switching function44 applied to Lennard-Jones interactions between 8 and 10 Å, an isotropic correction to account for pressure contributions from Lennard-Jones interactions beyond the cutoff,45 and the particle mesh Ewald method46 to account for electrostatic interactions beyond the cutoff.

For the subsequent ABF simulations, simulation methodology was similar to the equilibration stage, with the following exceptions. There were no harmonic restraints on atom positions, ABF sampling was applied to the ϕ and ψ coordinates (as defined in the Introduction) with a bin width of 2.5° in both the ϕ and ψ direction, the masses of hydrogen atoms attached to any atoms defining ϕ or ψ were set to 12 Da, and there were no bond length constraints associated with these hydrogen atoms. The latter was necessary for consistency with the ABF implementation, and the increased masses allowed for a timestep of 0.002 ps with no perturbation to the configurational partition function except the lack of bond constraints for these few atoms. Each ABF trajectory was 100 million steps (200 ns). ABF was not applied in a given (ϕ, ψ) bin until 100 force samples had been collected for that bin; subsequently, the ABF was linearly ramped upward, achieving its full value once 200 force samples had been collected for that bin.

Each system, as defined by a particular disaccharide and cation combination, was constructed in triplicate, with each member in the triplicate having different (ϕ, ψ) values. These values were based upon the most favored three quadrants of (ϕ, ψ) space as determined by crystallographic distributions and molecular dynamics trajectories for O1 and O2 disaccharides. These exploratory molecular dynamics trajectories included both standard (i.e. non-biased) MD and ABF MD, both lasting 20 ns, and with the ABF MD using 10° × 10° bins for force sampling. Supporting Information Table S2 summarizes these data.

After generation of disaccharide coordinates based on the Supporting Information Table S2 data and force field internal geometries and with the reducing-end monosaccharide in the β-anomer form, the disaccharide was centered in a cubic box having water molecules placed at evenly spaced grid points, with box dimensions appropriate for the experimental density of water and with 12 water molecules in each dimension. As all the CS disaccharides have some degree of negative charge, cations were added to generate net-neutral systems. Cations were either Na+ or Ca2+. In the case of Na+, one cation was added for O disaccharides, two for A and C, and three for D and E. In the case of Ca2+, a Cl− may also have been included to achieve charge balance. Specifically, one Ca2+ and one Cl− were added for O disaccharides, one Ca2+ for A and C, and two Ca2+ and one Cl− for D and E. Ions were added in the center of box faces; if two ions were added, the faces shared an edge, and if three, a corner. After equilibration, box edge lengths were ~37 Å.

ΔG(ϕ, ψ) was computed by integrating ABF data using the “abf_integrate” utility program33 included with the NAMD distribution and described in the NAMD ABF documentation. For non-biased MD data, ΔG(ϕ, ψ) was computed simply as -RT ln(n), where n is the number of samples in a given (ϕ, ψ) bin. As an initial control measure, data were generated from non-biased MD and compared to ABF data. This was done for the O1 and O2 disaccharides with Na+. Non-biased MD used the same protocol as used for equilibration, with the exceptions of no restraints and 200 ns of sampling. These data are in Supporting Information Figure S1 and confirm ABF generates expected results for this system.

With regard to error estimates and statistical testing, variability in PMF values ΔG(ϕ, ψ) for triplicate data for a given system (i.e. 3 × 200 ns) is reported as sample standard deviation s (Supporting Information Figures S2-S5), and statistical significance testing to compare data between systems is done using Welch's t test. For post-run analysis of disaccharide properties, snapshots were extracted from the trajectory files for which snapshots had been saved every 5000 steps (10 ps). Snapshots representative of a particular (ϕ, ψ) value were defined as all those from all three 200-ns ABF trajectories for a given disaccharide where both dihedral angles were within ±5° of the target (ϕ, ψ). Analytical solvent accessible surface areas47-48 were computed using force field Lennard-Jones radii and a probe radius of 1.5 Å.

Results and Discussion

CS disaccharide backbone thermodynamics for O1 and its sulfated analogs

The complete ΔG(ϕ, ψ) surfaces for the O1 disaccharide and its sulfated analogs A1, C1, D1, and E1 (collectively referred to as “Type 1” disaccharides here) in the presence of neutralizing sodium are all shown in Supporting Information Figure S2. As discussed below, the O1 ΔG(ϕ, ψ) surface provides a reference template, and sulfation effects can be interpreted based upon the correlated perturbations to this template, which can be substantial in magnitude (i.e. > 2 kcal/mol).

The O1 disaccharide has a single broad thermodynamically-important ΔG(ϕ, ψ) minimum

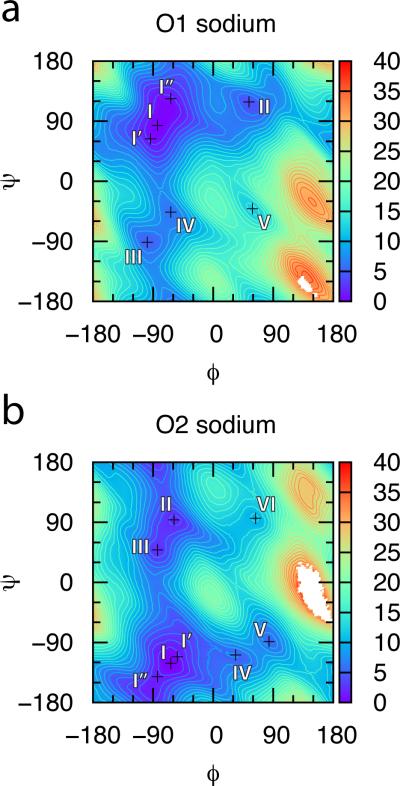

The O1 disaccharide global minimum at (ϕ, ψ) = (−83.75, 83.75) (Table 1) is located in a broad free energy basin. Taking the basin as encompassing ΔG(ϕ, ψ) values within 1 kcal/mol of the global minimum, this basin spans 30° in the ϕ direction and 60° in the ψ direction (Figure 2a). The next distinct minimum is centered at (53.75, 118.75) and is fully 4 kcal/mol higher in free energy, making it essentially irrelevant as fewer than 0.2% of conformations in an ensemble will be in this state.

Table 1.

Free energy minima in Type 1 disaccharides with neutralizing sodium.

| ϕ | ψ | ΔG(ϕ, ψ)a | ΔΔG(ϕ, ψ)a,b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | A1 | C1 | D1 | E1 | |||

| I | −83.75 | 83.75 | 0 | 2.53 ** | 0.07 n.s. | 0.28 ** | 2.22 ** |

| I’ | −93.75 | 63.75 | 0.62 | 4.08 ** | 0.17 n.s. | 0.56 ** | 3.44 ** |

| I” | −63.75 | 123.75 | 0.78 | −0.36 ** | −0.09 n.s. | 0.53 ** | −0.37 n.s. |

| II | 53.75 | 118.75 | 4.06 | −0.32 n.s. | −0.16 n.s. | 3.09 * | −1.15 n.s. |

| III | −98.75 | −91.25 | 5.10 | −1.02 n.s. | −0.28 n.s. | 0.49 n.s. | −1.09 n.s. |

| IV | −63.75 | −46.25 | 5.99 | 0.68 n.s. | −0.45 n.s. | 2.45 * | 0.59 n.s. |

| V | 58.75 | −41.25 | 11.66 | 8.39 ** | 0.53 n.s. | 3.25 ** | 8.37 ** |

Values are in kcal/mol.

Relative to the corresponding O1 values.

indicates p-value < 0.01

p-value < 0.05

p-value ≥ 0.05.

Statistically significant changes > 2 kcal/mol are in bold.

Figure 2.

ΔG(ϕ, ψ) for (a) O1 and (b) O2 CS disaccharides with neutralizing sodium cations. Free energy values are in kcal/mol and contours are every 1 kcal/mol.

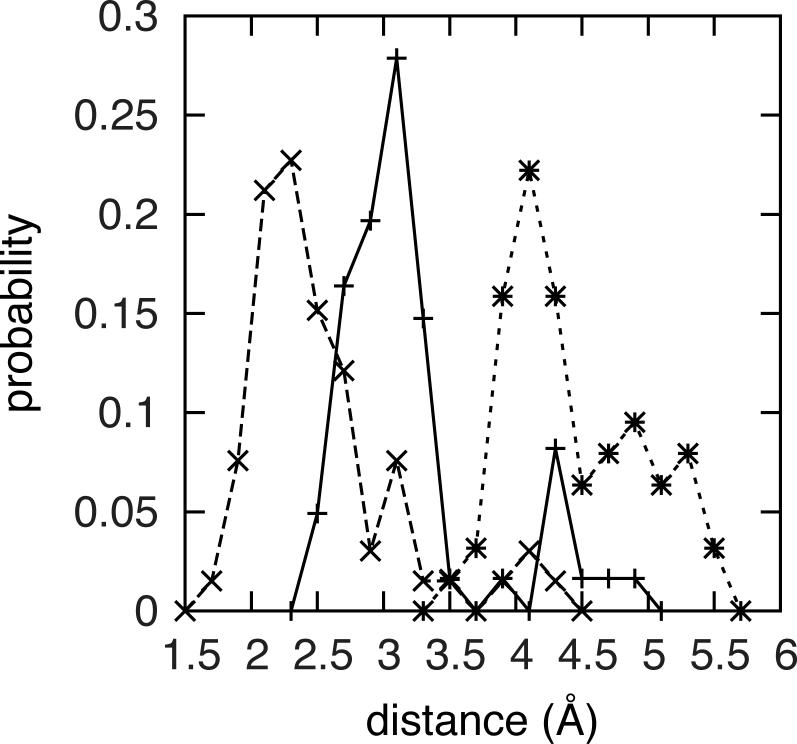

ABF simulation snapshots populating the global minimum basin have two notable characteristics: there is a lack of consistent intramolecular hydrogen bonding interactions between the constituent monosaccharides, and the disaccharide is in an extended conformation. In the basin, disaccharide geometries can potentially support a hydrogen bond between GalNAc 4-OH and GlcA Oring. However, hydrogen bond distance data show that only one region of the basin consistently supports this hydrogen bond, namely the I’ location (Figure 2, 3). In going from I’’ toward I’ via I, the two functional groups move progressively closer to each other, which enables favorable hydrogen bond lengths in the I’ corner of the basin (Figure 3). Therefore, this hydrogen bonding interaction is not critical to the stability of the global free energy minimum.

Figure 3.

GalNAc 4-OH to GlcA Oring hydrogen bond length distributions in the O1 disaccharide global free-energy basin. Data are for the I’’ (*), I (+), and I’ (x) locations.

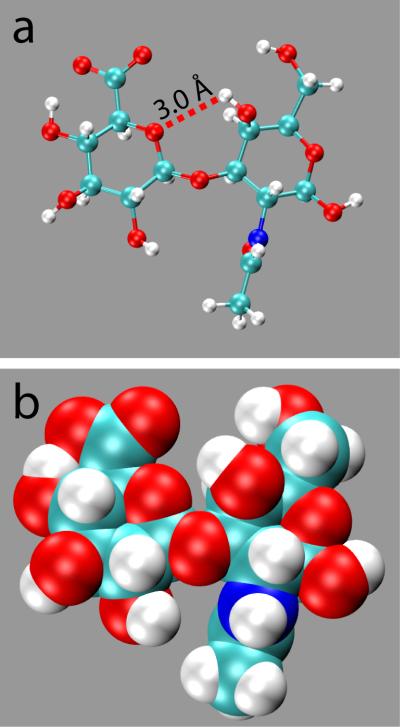

While the changes in (ϕ, ψ) going from I’’ toward I’ via I are sufficient to affect intramolecular hydrogen bonding, they are still small enough to have minimal effect on the overall shape of the disaccharide. That is, throughout the basin the disaccharide is in an extended conformation, which allows substantial exposure of its polar and charged functional groups to water. Of particular note is the solvent-exposed nature of the GlcA – COO− moiety. It is the only functional group in the disaccharide that is charged, and therefore is expected to strongly prefer being solvent exposed. Using the analytical solvent accessible surface area (SASA)47 as a measure, the degree of exposure of the – COO− group is unaltered when comparing conformations from these three regions of the basin (Table 2a). Figure 4 is a representative snapshot from the I location and demonstrates the extended conformation of the O1 disaccharide with solvent-exposed functional groups, along with the relative positioning of the GalNAc 4-OH and GlcA Oring functionalities.

Table 2.

Conformation-dependent charge burial in ABF simulations of Type 1 disaccharides with neutralizing sodium.

| a) O1 | |

|---|---|

| SASAa –COO− | |

| I” | 99.6 (2.8) |

| I | 95.3 (3.5) |

| I’ | 94.7 (3.4) |

| b) A1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Distanceb | SASAa –SO3− | SASAa –COO− | |

| I” | 6.65 (0.29) | 110.5 (4.7) | 97.6 (3.2) |

| I | 5.01 (0.25) | 99.2 (4.7) | 85.4 (3.4) |

| I’ | 4.56 (0.25) | 96.0 (4.2) | 81.8 (2.8) |

| c) E1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Distanceb | SASAa –SO3− | SASAa –COO− | |

| I” | 6.63 (0.29) | 108.8 (5.2) | 97.0 (3.9) |

| I | 4.97 (0.24) | 100.0 (3.9) | 84.0 (4.7) |

| I’ | 4.60 (0.25) | 95.5 (4.3) | 82.0 (3.0) |

Mean (standard deviation) solvent accessible surface area in Å2.

Mean (standard deviation) distance between –SO3− S atom and –COO− C atom in Å.

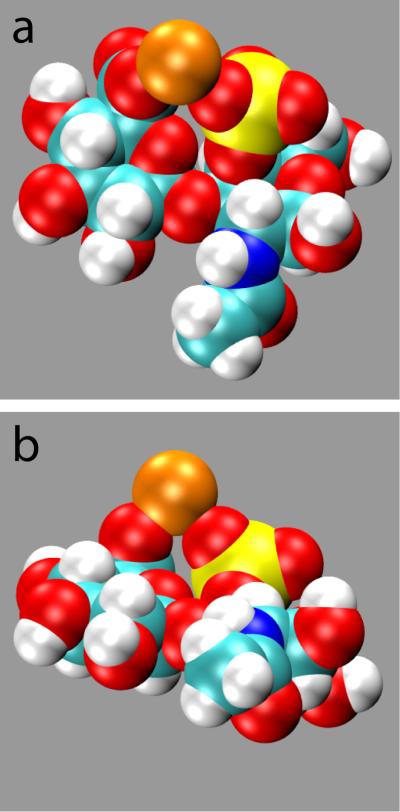

Figure 4.

Representative O1 disaccharide conformation from minimum I. (a) Balls-and-sticks representation with the GalNAc 4-OH to GlcA Oring hydrogen bond. (b) van der Waals representation.

4-O-sulfation of GalNAc shrinks the Type 1 disaccharide global ΔG(ϕ, ψ) minimum basin

Both the A1 and E1 CS disaccharides have 4-O-sulfation of GalNAc (Supporting Information Table S1). In both of these disaccharides, the global minimum basin shrinks relative to that for O1, with increases in ΔG(ϕ, ψ) of more than 2 kcal/mol at both the I and I’ locations (Table 1, Supporting Information Figure S2). Looking at the trend in ΔΔG(ϕ, ψ) for I, I’, and I’’ for these two disaccharides (Table 1), ΔG(ϕ, ψ) becomes steadily less favorable with decreasing ϕ and decreasing ψ. A1 and E1 MD snapshots at I, I’, and I’’ show that as ϕ and ψ decrease (i.e. I’’ → I → I’) the GalNAc – SO3− and GlcA –COO− groups move into closer and closer contact. The resulting decreasing distance between these two moieties has two effects: like charges are brought closer together and the solvent-accessible surface area of both groups decreases (Table 2b, c). Both of these are physically unfavorable, with the former resulting in increased charge-charge repulsion and the latter in decreased solvation. This is in contrast to the unsulfated O1, where such changes in (ϕ, ψ) do not bury the –COO− group (Table 2a).

Another effect of the sulfation is the loss of the hydrogen bond donor 4-OH in unsulfated GalNAc. Recalling that, based on distance (Figure 3), its interaction with GlcA Oring in the O1 disaccharide was most favorable in the I’ corner of the basin, the loss of hydrogen bonding is also an explanation for destabilization of I’ upon 4-O-sulfation. In contrast, the lack of significant shift among the I’’, II, III, and IV ΔG's upon this sulfation of GalNAc (Table 1: ΔΔG's for A1 and E1) suggests hydrogen bonding did not contribute to relative stability of the I’’ region of the basin, which is consistent with the long hydrogen bond lengths for this conformation (Figure 3).

6-O-sulfation of GalNAc has no effect on Type 1 disaccharide backbone thermodynamics

The global and local ΔG(ϕ, ψ) minima for C1, which is GlcA-GalNAc(6S), are the same as for the unsulfated O1 disaccharide (Table 1). Likewise, the ΔG(ϕ, ψ) minima for E1, which is GlcA-GalNAc(4S,6S), are the same as for the A1 disaccharide GlcA-GalNAc(4S). That is, the addition of the 6-O-sulfate to a given Type 1 disaccharide does not notably perturb the backbone energetics, suggesting that the (ϕ, ψ) conformational properties are independent of the net charge and hydrogen bond donor capacity associated with the GalNAc carbon 6 position. This finding also suggests that this moiety on GalNAc residue i does not interact with the upstream GlcA residue i+1 (where residue numbering increases going away from the reducing end), leaving open the possibility of its interaction either with the adjacent downstream GlcA i-1 and/or other residues in other glycosaminoglycan chains, for example in the context of a highly-glycosylated proteoglycan.

2-O-sulfation of GlcA destabilizes secondary minima

Keeping in mind that the global minimum basin is the only thermodynamically relevant minimum, other minima are substantially destabilized by 2-O-sulfation of GlcA. For example, minimum II, which is +4 kcal/mol relative to the global minimum in O1 (Figure 2, Table 1), is destabilized by another 3 kcal/mol upon 2-O-sulfation, as occurs in the D1 disaccharide (Table 1). And, the minima at IV and V are similarly destabilized in D1 relative to O1 (Table 1). Comparing snapshots from these three minima, taken from the triplicate O1 and triplicate D1 ABF simulations, does not provide an obvious explanation for the shift in thermodynamics. That is, there do not appear to be particular interactions that are either missing or expected to be destabilizing in the D1 conformations relative to the O1 conformations. Another possible explanation is that the global minimum basin is stabilized by sulfation at GlcA carbon 2. Indeed, this seems plausible, as the spatial location of the sulfate group in the global minimum is such that it can and does hydrogen bond with the amide proton on GlcNAc. However, we do note that the 2.5-3 kcal/mol destabilization at II and IV does not cross the p < 0.01 threshold in either case (Table 1).

CS disaccharide backbone thermodynamics for O2 and its sulfated analogs

The O2 disaccharide has two broad thermodynamically important ΔG(ϕ, ψ) minima

The most obvious difference between the backbone energetics of the O1 versus the O2 disaccharide is that the O2 disaccharide has thermodynamically relevant minima in two of the four quadrants of the (ϕ, ψ) space as opposed to in just one for O1. Recalling that the secondary minimum II for O1 is +4 kcal/mol in free energy relative to the global basin, the secondary minimum II for O2 is only +1.7 kcal/mol (Table 3). Like O1, the global minimum basin is wide, spanning 30° in the ϕ direction and 60° in the ψ direction (Figure 2b). While the secondary minimum at II is somewhat smaller, it is separated by a negligible barrier from the local minimum at III (Figure 2b). Taking II and III together as a single basin, this secondary, thermodynamically relevant basin is similar in size to that of the global minimum. Therefore, the I basin and the II/III basin define unique backbone conformations that are both significantly populated under standard conditions and also allow for backbone flexibility within the basin.

Table 3.

Free energy minima in Type 2 disaccharides with neutralizing sodium.

| ϕ | ψ | ΔG(ϕ, ψ)a | ΔΔG(ϕ, ψ)a,b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2 | A2 | C2 | D2 | E2 | |||

| I | −63.75 | −121.25 | 0 | 0.06 n.s. | 0.09 n.s. | 0.20 n.s. | 0.19 n.s. |

| I’ | −53.75 | −111.25 | 0.60 | 0.30 n.s. | 0.78 * | 0.38 n.s. | 0.96 * |

| I” | −83.75 | −141.25 | 1.21 | 0.08 n.s. | −0.10 n.s. | 0.61 ** | −0.37 n.s. |

| II | −58.75 | 93.75 | 1.66 | 0.88 n.s. | 0.53 n.s. | −0.15 n.s. | 1.50 n.s. |

| III | −83.75 | 48.75 | 2.28 | −0.30 n.s. | 2.65 ** | 2.09 * | 3.66 * |

| IV | 33.75 | −108.75 | 4.88 | −0.15 n.s. | 3.74 * | 2.79 * | 3.75 * |

| V | 83.75 | −88.75 | 5.34 | 2.60 * | 2.63 n.s. | 1.65 n.s. | 4.00 * |

| VI | 63.75 | 96.25 | 9.76 | −0.99 n.s. | 1.67 * | 1.81 * | 0.69 n.s. |

Values are in kcal/mol.

Relative to the corresponding O2 values.

indicates p-value < 0.01

p-value < 0.05

p-value ≥ 0.05.

Statistically significant changes > 2 kcal/mol are in bold.

GalNAc 6-O-sulfation narrows both thermodynamically important minima

The ΔG(ϕ, ψ) surfaces for the C2, D2, and E2 disaccharides (Supporting Information Figure S3) share some common features. The III location, which can be considered part of the II basin, is destabilized in all three cases (Table 3). This is also the case for the IV location, which can be viewed as an extension of the I basin into the adjacent quadrant (Figure 2b). All three of these disaccharides share a common feature that distinguishes them from the other Type 2 disaccharides: sulfation at the 6 position. Snapshots of ABF sampling in the III location for O2 provide a simple explanation. In this backbone geometry, rotation of the exocyclic group on GalNAc allows its 6-OH to act as a hydrogen bond donor to the GlcA carboxylate. In this collection of snapshots, 93% had a 6-OH proton to carboxylate oxygen distance of < 2.5 Å, demonstrating the strength of this interaction, which is not possible with the conversion of the hydroxyl to a sulfate. The situation is similar for the IV location in that this interaction is also possible in this backbone geometry, and snapshots from the O2 ABF trajectories demonstrate a similarly-high frequency for this hydrogen bonding interaction. Therefore this modification to the O2 disaccharide narrows both of the thermodynamically accessible basins by precluding the possibility of a hydrogen bond between the exocyclic hydroxyl of GlcNAc (now sulfated) and the carboxylate of GlcA.

GalNAc 4-O-sulfation destabilizes a secondary minimum

While the minimum at V is +5 kcal/mol (Table 3), for the sake of completeness it is worth noting that this minimum is destabilized by GalNAc 4-O-sulfation, as occurs in the A2 and E2 disaccharides. Similar to GalNAc 6-O-sulfation, 4-O-sulfation precludes the formation of an inter-monosaccharide hydrogen bond involving the GlcA carboxylate. However, in this case, the unsulfated O2 is stabilized by 4-OH as the hydrogen bond donor, and 96% of snapshots have a 4-OH proton to carboxylate oxygen distance of < 2.5 Å.

Cation binding and effects on ΔG(ϕ, ψ)

Recalling that all disaccharides in this study carry negative charge in the form of a carboxylate group on GlcA, and that most of the disaccharides carry additional negative charge in the form of sulfate groups (Supporting Information Table S1), there exists the possibility of charge-charge interactions between CS disaccharides and solution counterions. Analysis of all of the ABF trajectories shows a clear trend in cation binding across all systems, as discussed below.

Free energy values for the minima in O1 ABF simulations with neutralizing sodium vs. calcium cations are essentially identical: none of the differences are statistically significant, and nearly all are less than or equal to 0.5*RT (Table 4) and are therefore substantially less physically significant than, for example, some of the effects of sulfation. Qualitatively, the full surfaces are also indistinguishable (Figures S2 “O1 sodium” and S4 “O1 calcium”). These results suggest several possibilities. One is that neither of the cation types interacts with the disaccharide. Another is that cation interactions do not affect inter-monosaccharide interactions. A third is that, while cation interactions do affect inter-monosaccharide interactions, the effects are independent of the ion identity.

Table 4.

Calcium effects on free energy minima in Type 1 disaccharides.

| ϕ | ψ | ΔΔG(ϕ, ψ)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | A1 | C1 | D1 | E1 | |||

| I | −83.75 | 83.75 | 0.10 n.s. | −0.15 n.s. | −0.05 n.s. | −0.10 n.s. | −0.63 * |

| I’ | −93.75 | 63.75 | 0.30 n.s. | −1.18 n.s. | 0.17 n.s. | −0.14 n.s. | −2.07 * |

| I” | −63.75 | 123.75 | −0.21 n.s. | −0.02 n.s. | −0.04 n.s. | 0.15 n.s. | 0.14 n.s. |

| II | 53.75 | 118.75 | −0.35 n.s. | 0.16 n.s. | −0.07 n.s. | −0.68 * | 1.84 * |

| III | −98.75 | −91.25 | −0.16 n.s. | 2.21 n.s. | 0.56 n.s. | 0.10 n.s. | 2.52 n.s. |

| IV | −63.75 | −46.25 | 0.35 n.s. | 2.10 * | 0.85 n.s. | −0.15 n.s. | 2.45 * |

| V | 58.75 | −41.25 | 0.74 n.s. | −0.74 n.s. | 0.16 n.s. | −0.47 n.s. | −5.07 * |

ΔΔG(ϕ, ψ) = ΔG(ϕ, ψ)calcium - ΔG(ϕ, ψ)sodium.

Values are in kcal/mol.

“**” indicates p-value < 0.01

p-value < 0.05

p-value ≥ 0.05.

Statistically significant changes > 2 kcal/mol are in bold.

Minimum disaccharide-ion distance data from snapshots of the I, I’, I’’, II, and III locations demonstrate that there is in fact a strong difference in ion binding to the O1 disaccharide. 82% of the snapshots had calcium cation directly bound to the disaccharide (as defined by a disaccharide-ion distance < 3 Å), in stark contrast to the 0.6% of snapshots in the triplicate trajectories with sodium (Supporting Information Table S3). Furthermore, if only binding to the –COO− group is considered, in the case of calcium, the figure remains 82% while it reduces to 0.3 % for sodium. The conclusion is therefore that calcium cation and not sodium cation binds strongly to the O1 disaccharide, that this binding is specific to the –COO− group, and that this ion binding or lack thereof does not affect the thermodynamics of the O1 backbone.

A similar conclusion can be drawn for the sulfated derivatives of O1. Sodium binding for these Type 1 disaccharides is never more than 10%, in strong contrast to calcium binding of > 80% (Supporting Information Table S3). When considering just the –COO− group, the calcium data are essentially the same as when considering the complete disaccharides, whereas when considering just the –SO3− groups the calcium data show binding typically < 10% (Supporting Information Table S3). Therefore, regardless of sulfation state, for Type 1 disaccharides, calcium binding is via the –COO− group. With regard to cation effects on backbone thermodynamics, though lacking in statistical significance, adding calcium looks to reverse the destabilizing effect on I’ that 4-O-sulfation on GalNAc has on the A1 and E1 disaccharides (Tables 1 and 4). Recalling that the observed destabilization is due to a combination of charge-charge repulsion and charge burial, a single calcium cation can reverse these effects by pairing with both charged groups and forming a bridging interaction (Figure 5). This effect is limited to the I’ area of the global minimum basin because, as discussed previously in relation to the Table 2 data, charge-charge repulsion and charge burial are less of an issue at the I and I’’ locations.

Figure 5.

Representative A1 disaccharide conformation from minimum I’ with a bridging calcium cation between the –COO− and –SO3− groups. (a) and (b) are two views of the same snapshot, and the calcium cation is colored orange.

There are substantial similarities in cation effects on Type 2 vs. Type 1 disaccharides: calcium cation and not sodium cation binds strongly to Type 2 disaccharides, binding is specific to the –COO− group, and calcium binding has no effect on backbone thermodynamics of thermally-accessible conformations when considering the unsulfated disaccharide and limited effects otherwise. As with Type 1 disaccharides, sodium binding is limited to < 10% while calcium binding is typically > 80% (Supporting Information Table S3). Calcium binding when considering just the –COO− group is nearly identical to the figures that consider the complete disaccharide, implying that any sulfate binding, which is limited to < 20%, is due to simultaneous binding of the calcium with the –COO− group (Supporting Information Table S3).

The one apparently large effect on thermally-accessible conformations is limited to the II state of E2, which is stabilized by 2 kcal/mol by calcium binding (Table 5). However, visualization of all ABF snapshots representative of this location provides no obvious explanation for how calcium binding might contribute to this apparent stabilization. That is, while the –COO− group is bound to Ca2+ in these snapshots, there are no bridging interactions with it and either of the –SO3− groups, simply because the backbone geometry of E2 and the II location places these latter groups, both located on GalNAc, too far away from the bound Ca2+. It is worth noting that the apparent stabilization has 0.01 ≤ p < 0.05, and that the apparent destabilization relative to O2 in simulations with Na+, though 1.5 kcal/mol in magnitude, has p > 0.05 (Table 3). Taking these points into consideration, it is possible that there is in fact no cation effect on E2 with regard to the stability of the II conformational state.

Table 5.

Calcium effects on free energy minima in Type 2 disaccharides.

| ϕ | ψ | ΔΔG(ϕ, ψ)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2 | A2 | C2 | D2 | E2 | |||

| I | −63.75 | −121.25 | 0.15 n.s. | −0.01 n.s. | −0.03 n.s. | 0.20 n.s. | −0.11 n.s. |

| I’ | −53.75 | −111.25 | −0.04 n.s. | −0.25 n.s. | −0.73 ** | −0.32 n.s. | −0.85 ** |

| I” | −83.75 | −141.25 | 0.64 n.s. | 0.27 n.s. | 0.71 n.s. | 0.53 n.s. | 0.01 n.s. |

| II | −58.75 | 93.75 | −0.25 n.s. | −1.04 n.s. | −0.71 n.s. | −0.69 n.s. | −2.05 * |

| III | −83.75 | 48.75 | −1.17 * | −1.51 n.s. | −1.99 * | −1.57 * | −3.88 ** |

| IV | 33.75 | −108.75 | 1.01 * | 0.86 n.s. | −2.45 * | −1.48 * | −3.08 * |

| V | 83.75 | −88.75 | 2.98 * | −0.42 n.s. | 0.42 n.s. | 0.47 n.s. | −2.27 n.s. |

| VI | 63.75 | 96.25 | 0.36 n.s. | 0.01 n.s. | −1.40 n.s. | −0.08 n.s. | −2.24 * |

ΔΔG(ϕ, ψ) = ΔG(ϕ, ψ)calcium - ΔG(ϕ, ψ)sodium.

Values are in kcal/mol.

indicates p-value < 0.01

p-value < 0.05

p-value ≥ 0.05.

Statistically significant changes > 2 kcal/mol are in bold.

Conclusions

The CS family of GAGs is built from 10 unique disaccharides characterized by their glycosidic linkages and sulfation patterns. To investigate differential sulfation and cation binding effects on CS glycosidic “backbone” thermodynamics, we have used all-atom explicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulation combined with Adaptive Biasing Force sampling to produce the full ΔG(ϕ, ψ) surfaces for these 10 CS disaccharides. The high precision and 2.5° × 2.5° resolution of these data enabled the observation of both sulfation and ion binding effects on ΔG(ϕ, ψ).

Sulfation of Type 1 disaccharides (i.e. GlcAβ1-3GalNAcβ and derivatives) in the absence of ion binding has several notable effects on backbone thermodynamics. The O1 disaccharide, which lacks sulfate, has one large thermodynamically important minimum. GalNAc 4-O-sulfation results in a smaller global minimum compared to the O1 reference, while 2-O-sulfation destabilizes secondary minima, which are already very sparsely populated in O1. Meanwhile, 6-O-sulfation of Type 1 disaccharides has no effect on backbone thermodynamics. In contrast, Type 2 disaccharides (i.e. GalNAcβ1-4GlcAβ and derivatives) have two broad thermodynamically important minima in the absence of ion binding. Also in contrast to Type 1 disaccharides, GalNAc 6-O-sulfation leads to narrowing of both of these low free-energy minima. And, it is GalNAc 4-O-sulfation that further destabilizes sparsely populated secondary minima in these constructs.

Calcium concentrations are much greater in extracellular space than in the cytoplasm, which is relevant to CS given its incorporation into extracellular proteoglycans (PGs). This therefore makes it important to understand how Ca2+ binding can affect ΔG(ϕ, ψ). From the simulation data, calcium binds strongly to CS disaccharides (~85% bound) via the –COO− functional group of GlcA, whereas sodium does not (< 10% bound). In some cases, sulfation leads to unfavorable charge-charge interactions between –COO− and –SO3−. In backbone conformations where this does occur, Ca2+ can bind to both functional groups simultaneously and bridge the interaction, which reverses this destabilization. This latter finding is likely relevant in the extracellular space, where polyanionic GAG chains of hundreds of monosaccharides, as constituents of PGs, can be found in close proximity4, 49 resulting in high negative charge density.50

The present free energy data are of high precision and resolution given current standards for molecular dynamics simulations using all-atom additive force fields. These force fields are defined as having a single interaction site for each atom, including hydrogen atoms, and with each interaction site carrying a constant partial charge that contributes to the total system energy through the Coulomb electrostatic equation.51-52 However, high precision and resolution is different than high accuracy, which has to do with how close the simulation data are to the data that would result from corresponding “real” experiments. Of course, no direct answer regarding accuracy is possible since there do not exist any methods to perform the corresponding real experiments.

An alternative might be to compare the results here to those from more “realistic” models. At the upper limit would be high-level quantum mechanical calculations with an appropriately-large basis set.53 Computational expense limits these to a small number of static snapshots either with a implicit representation of solvent,54 which introduces a potentially large approximation, or the need to decide on the placement of some select discrete water molecules, which introduces arbitrariness. Furthermore, single point energies from static snapshots are not equivalent to thermodynamic free energies, and it is free energies that are most relevant under laboratory and biological conditions. We emphasize that the additive force field results presented here are indeed true free energies of systems with explicit water molecules and ions and computed by integrating the values of average forces. These average forces are from constant-temperature, constant-pressure ensembles, and their integration does yield true free energy per the reversible work theorem.55

On the other side of the spectrum of more realistic models are all-atom polarizable force fields, which allow for rearrangement of the charge distribution of the system in response to the atomic positions during the simulation while still operating in the molecular mechanics framework.56 These models tend to be no greater than an order of magnitude more computationally demanding than all-atom additive force fields, allowing for the possibility of sampling thermodynamic ensembles in order to compute free energies. However, since the development of additive force fields is a decade or more ahead of polarizable models, the strengths of weaknesses of the former are better understood, including difficulties handling ions.57 To address some of this characterized difficulty, interaction-specific ion Lennard-Jones parameters have been previously developed, and were employed in the current work through their standard inclusion in the CHARMM C36 force field (available at http://mackerell.umaryland.edu/charmm_ff.shtml).

The complete ΔG(ϕ, ψ) data presented here complement existing structural data for CS, which are discussed by both Yu23 and coworkers and Sattelle and coworkers22 as part of their own studies on CS oligosaccharides and include NMR,22-23, 58 X-ray,17, 20-21 and computational23-24, 58-59 work. The current results for the unsulfated disaccharides are in line with an NMR-derived structural model of unsulfated CS hexasaccharide22 (PDB ID: 2KQO), for which (ϕ1, ψ1) = (−72°, 108°) and (ϕ2, ψ2) = (−73°, −117°): the corresponding ΔG values for the O1 and O2 disaccharides here are only +0.2 kcal/mol and +0.3 kcal/mol and the NMR geometries are located in the global free-energy basins of the respective disaccharides (Tables 1 and 3, and Figure 2).

While most of the above previous results are consistent with regard to the global free-energy minimum geometries of both (ϕ1, ψ1) and (ϕ2, ψ2), the discussed X-ray fiber diffraction data suggest a preferred ψ2 value of ~180°.21 However, that geometry (PDB ID: 2C4S; (ϕ2, ψ2) = (−98°, −174°)) is still within the bounds of the wide global free-energy minimum basin for O2 (Figure 2b; ΔG = +2.0 kcal/mol), and therefore this alternative observed backbone conformation is not completely surprising. The fiber diffraction data were for calcium chondroitin 4-sulfate. Since neither sulfation nor calcium binding have significant effects on the energetics of the relevant basin (i.e. O2 vs. A2, Table 3 and Table 5), it is likely that the crystal environment plays a strong role in stabilizing this alternative backbone geometry. For example, in the structure, the –COO− group directly binds a Ca2+ cation. The cation in turn is complexed with an ordered water molecule that hydrogen bonds with the amide nitrogen in GlcNAc. This crystallographic interaction is sufficiently important to cause conversion from a 3-fold helical conformation in the presence of Na+ to a 2-fold structure in the case of the Ca2+ salt.21 Importantly, the structure of the former form20 (PDB ID: 1C4S) has (ϕ2, ψ2) = (−80°, −129°), and ΔG = +0.8 kcal/mol for this conformation for both O2 and A2 with sodium. And, that crystal form has no Na+ ions within 3 Å of either the –COO− or –SO3− oxygen atoms, in agreement with the lack of Na+ binding in solution observed here.

Not represented in the above survey of experimental data is the thermodynamically accessible II/III basin for Type 2 disaccharides. While quantum mechanical energies across the entire (ϕ, ψ) coordinate were used in the force field parametrization,29 it is possible that the observed stability of this basin for Type 2 disaccharides is a force field artifact. Searches (Nov. 5, 2014) of the GlyTorsion database60 for “b-D-Galp-(1-4)-b-D-Glcp” and “b-D-Galp-(1-4)-a-D-Glcp” yielded 414 and 85 hits respectively, with 3 hits for each of the two searches being located in the region of this basin. Therefore, there is circumstantial experimental structural evidence that this secondary basin is, in fact, thermodynamically accessible and therefore biologically relevant.

Another correlate with existing data is the relative importance of the GalNAc 4-OH to GlcA Oring hydrogen bond in -4GlcAβ1-3GalNAcβ1-. In interpreting their NMR structure of unsulfated CS hexasaccharide, Satelle and coworkers noted that, from inspection of the interatomic distance, this interaction is much less strong than the analogous interaction in hyaluronan,22 in which GlcNAc replaces GalNAc. Their observation is confirmed both by the hydrogen bond length distribution (Figure 3) and thermodynamic analysis (discussion on 4-O-sulfation effects in Type 1 disaccharides) here.

The present study entailed a total of 12,000 ns (200 ns/simulation × 10 disaccharides × 2 ion conditions × triplicate simulations) of all-atom explicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulations combined with Adaptive Biasing Force sampling to generate high resolution, high precision ΔG(ϕ, ψ) with coverage of the full (ϕ, ψ) coordinate. While the simulations were computationally demanding by current standards, they did yield true free energies that include both entropic and enthalpic contributions under conditions of constant temperature and pressure. Furthermore, the inclusion of explicit water molecules and ions meant the discrete nature of the components of the solution was accounted for when considering interaction between solution and disaccharide.

Previous computational results for the adiabatic molecular mechanics energy of chondroitin disaccharides as a function of (ϕ, ψ) provide an interesting point of reference.24 In those calculations, a dielectric constant of 80 was used to represent the aqueous environment. The resulting adiabatic energy surfaces, computed for the O, A, and C disaccharides, are very similar to the present free energy surfaces ΔG(ϕ, ψ) with regard to the location and shape of the global minima. The II regions of the surfaces were also comparable, with adiabatic energy values of +3-5 kcal/mol relative to the global minimum. This suggests that much of the conformational thermodynamics of these disaccharides is due to bonded and steric effects, since a dielectric constant of 80 practically negates the electrostatic contribution to the force field energy. That said, one important contrast is the +1.7 kcal/mol value of the O2 local ΔG(ϕ, ψ) minimum at II (Table 3) as compared to a value of +5 kcal/mol for the adiabatic energy.24 In terms of thermodynamic ensembles, the former value suggests that this local minimum has a 5% chance of being sampled as compared to a 0.03% chance for the latter value. Since biologically-relevant chondroitin chains can be on the order of hundreds of monosaccharides long, a 5% probability of sampling this local minimum would mean that a representative conformation of such a chain would have several “kinks” due to β1-4 linkages having this geometry. This would not be the case for a 0.03% probability.

Given their consistency with existing work on CS backbone conformations, the high-precision, high-resolution ΔG(ϕ, ψ) data for all ten CS disaccharides further validate the comprehensive CHARMM carbohydrate force field28-30 and the application of all-atom explicit-solvent MD simulations to the study of these systems.31, 61 It is anticipated that these data will be of utility in future efforts to build models of CS polymers, using, for example Monte Carlo approaches.24 Such modeling is especially relevant to understanding the structural biology of proteoglycans and can be used to interpret results of standard MD simulations. This is important because systematic and thorough biased MD studies are, for the foreseeable future, not practical for large proteoglycan systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professor Hideto Watanabe for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R15 GM099022), and used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE; allocation TG-MCB120007), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (grant ACI-1053575).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Monosaccharide sulfation sites, favored quadrants of (ϕ, ψ) space for O1 and O2 disaccharides, percent binding of sodium and calcium cations for all disaccharides, ΔG(ϕ, ψ) computed using standard (i.e. non-biased) molecular dynamics for O1 and O2 disaccharides, and ΔG(ϕ, ψ) and standard deviations in ΔG(ϕ, ψ) for all disaccharide systems studied are included as Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Silbert JE, Sugumaran G. Biosynthesis of Chondroitin/Dermatan Sulfate. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:177–186. doi: 10.1080/15216540214923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugahara K, Kitagawa H. Recent Advances in the Study of the Biosynthesis and Functions of Sulfated Glycosaminoglycans. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:518–527. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uyama T, Kitagawa H, Sugahara K. Biosynthesis of Glycosaminoglycans and Proteoglycans. Compr. Glycosci. 2007;3:79–104. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright DW, Mayne R. Vitreous Humor of Chicken Contains Two Fibrillar Systems: An Analysis of Their Structure. J. Ultra. Mol. Struct. R. 1988;100:224–234. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(88)90039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraemer PM. Complex Carbohydrates of Animal Cells: Biochemistry and Physiology of the Cell Periphery. In: Manson LA, editor. Biomembranes. Vol. 1. Springer; US: New York: 1971. pp. 67–190. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day AJ. The Structure and Regulation of Hyaluronan-Binding Proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1999;27:115–121. doi: 10.1042/bst0270115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearns AE, Vertel BM, Schwartz NB. Topography of Glycosylation and UDP-Xylose Production. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:11097–11104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikami T, Kitagawa H. Biosynthesis and Function of Chondroitin Sulfate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830:4719–4733. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter GK. Chondroitin Sulfate-Derivatized Agarose Beads: A New System for Studying Cation Binding to Glycosaminoglycans. Anal. Biochem. 1987;165:435–441. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter GK, Wong KS, Kim JJ. Binding of Calcium to Glycosaminoglycans: An Equilibrium Dialysis Study. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1988;260:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchisawa H, Okuzaki B.-i., Ichita J, Matsue H. Binding between Calcium Ions and Chondroitin Sulfate Chains of Salmon Nasal Cartilage Glycosaminoglycan. Int. Congr. Ser. 2001;1223:205–220. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maroudas A, Evans H. A Study of Ionic Equilibria in Cartilage. Connect. Tissue Res. 1972;1:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pomin VH. Solution NMR Conformation of Glycosaminoglycans. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2014;114:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherney MM, Lecaille F, Kienitz M, Nallaseth FS, Li Z, James MN, Bromme D. Structure-Activity Analysis of Cathepsin K/Chondroitin 4-Sulfate Interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:8988–8998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Kienetz M, Cherney MM, James MN, Bromme D. The Crystal and Molecular Structures of a Cathepsin K:Chondroitin Sulfate Complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;383:78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lunin VV, Li Y, Linhardt RJ, Miyazono H, Kyogashima M, Kaneko T, Bell AW, Cygler M. High-Resolution Crystal Structure of Arthrobacter aurescens Chondroitin AC Lyase: An Enzyme-Substrate Complex Defines the Catalytic Mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;337:367–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michel G, Pojasek K, Li Y, Sulea T, Linhardt RJ, Raman R, Prabhakar V, Sasisekharan R, Cygler M. The Structure of Chondroitin B Lyase Complexed with Glycosaminoglycan Oligosaccharides Unravels a Calcium-Dependent Catalytic Machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32882–32896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403421200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigden DJ, Jedrzejas MJ. Structures of Streptococcus pneumoniae Hyaluronate Lyase in Complex with Chondroitin and Chondroitin Sulfate Disaccharides. Insights into Specificity and Mechanism of Action. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:50596–50606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh K, Gittis AG, Nguyen P, Gowda DC, Miller LH, Garboczi DN. Structure of the DBL3x Domain of Pregnancy-Associated Malaria Protein VAR2CSA Complexed with Chondroitin Sulfate A. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:932–938. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winter WT, Arnott S, Isaac DH, Atkins ED. Chondroitin 4-Sulfate: The Structure of a Sulfated Glycosaminoglycan. J. Mol. Biol. 1978;125:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cael JJ, Winter WT, Arnott S. Calcium Chondroitin 4-Sulfate: Molecular Conformation and Organization of Polysaccharide Chains in a Proteoglycan. J. Mol. Biol. 1978;125:21–42. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sattelle BM, Shakeri J, Roberts IS, Almond A. A 3D-Structural Model of Unsulfated Chondroitin from High-Field NMR: 4-Sulfation Has Little Effect on Backbone Conformation. Carbohydr. Res. 2010;345:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu F, Wolff JJ, Amster IJ, Prestegard JH. Conformational Preferences of Chondroitin Sulfate Oligomers Using Partially Oriented Nmr Spectroscopy of 13C-Labeled Acetyl Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:13288–13297. doi: 10.1021/ja075272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez-Carvajal MA, Imberty A, Perez S. Conformational Behavior of Chondroitin and Chondroitin Sulfate in Relation to Their Physical Properties as Inferred by Molecular Modeling. Biopolymers. 2003;69:15–28. doi: 10.1002/bip.10304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufmann J, Möhle K, Hofmann HJ, Arnold K. Molecular Dynamics of a Tetrasaccharide Subunit of Chondroitin 4-Sulfate in Water. Carbohydr. Res. 1999;318:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(99)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cilpa G, Hyvönen MT, Koivuniemi A, Riekkola ML. Atomistic Insight into Chondroitin-6-Sulfate Glycosaminoglycan Chain through Quantum Mechanics Calculations and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:1670–1680. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neamtu A, Tamba B, Patras X. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Chondroitin Sulfate in Explicit Solvent: Point Charge Water Models Compared. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2013;47:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guvench O, Greene SN, Kamath G, Brady JW, Venable RM, Pastor RW, MacKerell AD., Jr. Additive Empirical Force Field for Hexopyranose Monosaccharides. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:2543–2564. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guvench O, Hatcher ER, Venable RM, Pastor RW, MacKerell AD., Jr. CHARMM Additive All-Atom Force Field for Glycosidic Linkages between Hexopyranoses. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:2353–2370. doi: 10.1021/ct900242e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guvench O, Mallajosyula SS, Raman EP, Hatcher E, Vanommeslaeghe K, Foster TJ, Jamison FW, Jr., MacKerell AD., Jr. CHARMM Additive All-Atom Force Field for Carbohydrate Derivatives and Its Utility in Polysaccharide and Carbohydrate-Protein Modeling. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:3162–3180. doi: 10.1021/ct200328p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mallajosyula SS, Guvench O, Hatcher E, MacKerell AD., Jr. CHARMM Additive All-Atom Force Field for Phosphate and Sulfate Linked to Carbohydrates. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2012;8:759–776. doi: 10.1021/ct200792v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Darve E, Rodríguez-Gómez D, Pohorille A. Adaptive Biasing Force Method for Scalar and Vector Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:144120. doi: 10.1063/1.2829861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hénin J, Fiorin G, Chipot C, Klein ML. Exploring Multidimensional Free Energy Landscapes Using Time-Dependent Biases on Collective Variables. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:35–47. doi: 10.1021/ct9004432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kalé L, Schulten K. Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durell SR, Brooks BR, Ben-Naim A. Solvent-Induced Forces between Two Hydrophilic Groups. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:2198–2202. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooks BR, Brooks CL, 3rd, MacKerell AD, Jr., Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, et al. CHARMM: The Biomolecular Simulation Program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. CHARMM: A Program for Macromolecular Energy, Minimization, and Dynamics Calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyamoto S, Kollman PA. Settle: An Analytical Version of the SHAKE and RATTLE Algorithm for Rigid Water Models. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:952–962. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kubo R, Toda M, Hashitsume N. Statistical Physics II: Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics. 2 ed. Springer; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feller SE, Zhang Y, Pastor RW, Brooks BR. Constant Pressure Molecular Dynamics Simulation: The Langevin Piston Method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brünger A, Brooks CL, 3rd, Karplus M. Stochastic Boundary Conditions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations of ST2 Water. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1984;105:495–500. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinbach PJ, Brooks BR. New Spherical-Cutoff Methods for Long-Range Forces in Macromolecular Simulation. J. Comput. Chem. 1994;15:667–683. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen MP, Tildesley DJ. Computer Simulation of Liquids. Oxford University Press; Oxford, U.K.: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle Mesh Ewald: An N·Log(N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee B, Richards FM. The Interpretation of Protein Structures: Estimation of Static Accessibility. J. Mol. Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wodak SJ, Janin J. Analytical Approximation to the Accessible Surface Area of Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:1736–1740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hay ED. Cell Biology of Extracellular Matrix. Springer; US: New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayes WC, Mockros LF. Viscoelastic Properties of Human Articular Cartilage. J. Appl. Physiol. 1971;31:562–568. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guvench O, MacKerell AD., Jr. Comparison of Protein Force Fields for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;443:63–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-177-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monticelli L, Tieleman DP. Force Fields for Classical Molecular Dynamics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;924:197–213. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-017-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friesner RA. Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry: Methodology and Applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:6648–6653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408036102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomasi J, Mennucci B, Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2999–3093. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chandler D. Introduction to Modern Statistical Mechanics. Oxford University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopes PE, Guvench O, MacKerell AD., Jr. Current Status of Protein Force Fields for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1215:47–71. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1465-4_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roux B, Berneche S. On the Potential Functions Used in Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Ion Channels. Biophys. J. 2002;82:1681–1684. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75520-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blanchard V, Chevalier F, Imberty A, Leeflang BR, Basappa, Sugahara K, Kamerling JP. Conformational Studies on Five Octasaccharides Isolated from Chondroitin Sulfate Using NMR Spectroscopy and Molecular Modeling. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1167–1175. doi: 10.1021/bi061971f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Almond A, Sheehan JK. Glycosaminoglycan Conformation: Do Aqueous Molecular Dynamics Simulations Agree with X-Ray Fiber Diffraction? Glycobiology. 2000;10:329–338. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lutteke T, Frank M, von der Lieth CW. Carbohydrate Structure Suite (CSS): Analysis of Carbohydrate 3D Structures Derived from the PDB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D242–246. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sattelle BM, Almond A. Less Is More When Simulating Unsulfated Glycosaminoglycan 3D-Structure: Comparison of GLYCAM06/TIP3P, PM3-CARB1/TIP3P, and SCC-DFTB-D/TIP3P Predictions with Experiment. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:2932–2947. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.