Abstract

Purpose

Bariatric surgery is relatively new in Korea, and studies comparing different bariatric procedures in Koreans are lacking. This study aimed to compare the clinical outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and sleeve gastrectomy (SG) for treating morbidly obese Korean adults.

Materials and Methods

In this multicenter retrospective cohort study, we reviewed the medical records of 261 obese patients who underwent different bariatric procedures. Clinical outcomes were measured in terms of weight loss and resolution of comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Safety profiles for the procedures were also evaluated.

Results

In terms of weight loss, the three procedures showed similar results at 18 months (weight loss in 52.1% for SG, 61.0% for LAGB, and 69.2% for RYGB). Remission of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia was more frequent in patients who underwent RYGB (65.9%, 63.6%, and 100% of patients, respectively). Safety profiles were similar among groups. Early complications occurred in 26 patients (9.9%) and late complications in 32 (12.3%). In the LAGB group, five bands (6.9%) were removed. Among all patients, one death (1/261=0.38%) occurred in the RYGB group due to aspiration pneumonia.

Conclusion

The three bariatric procedures were comparable in regards to weight-loss outcomes; nevertheless, RYGB showed a higher rate of comorbidity resolution. Bariatric surgery is effective and relatively safe; however, due to complications, some bands had to be removed in the LAGB group and a relatively high rate of reoperations was observed in the RYGB group.

Keywords: Morbid obesity, bariatric surgery, outcomes, comparative study, Koreans

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a serious health problem for Western countries and a growing health concern for most countries in the Asia-Pacific region. In Korea, the prevalence of obesity in adults, defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2, has gradually increased from 29.2% in 2001 to 31.4% in 2011.1

Bariatric surgery is considered the most efficacious treatment for severe obesity in the long term. Bariatric surgery results in long-term weight-loss control, along with lifestyle improvements and amelioration of risk factors, within a decade after surgery.2 Furthermore, bariatric surgery is widely known to offer metabolic effects in patients with type II diabetes. One study demonstrated that diabetes remission, defined by blood glucose <110 mg/dL without diabetes medications, was 72.3% at 2 years and 30.4% at 15 years after bariatric surgery.3 Worldwide, metabolic/bariatric surgeries have more than doubled from 2003 to 2011: the most frequently performed bariatric in 2011 was the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), followed by sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB).4

Many bariatric surgeons prefer RYGB over SG or LAGB, because the former procedure is associated with better outcomes of weight loss and resolution of comorbidities. However, RYGB is also associated with higher rates of readmission and reoperation/intervention;5 hence, other surgeons prefer SG or LAGB over RYGB, because these procedures have a better safety profile.

Bariatric surgery is relatively new in Korea: the first laparoscopic bariatric procedure was performed in 2003.6 Accordingly, large comparative studies are still lacking. We conducted this study to compare the clinical outcomes of RYGB vs. SG vs. LAGB in an effort to outline which procedure should be considered optimal for treating obesity and its comorbidities in obese Korean adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and patient identification

This study applied a retrospective cohort design based on medical chart review. We collected data on 261 consecutive obese adults (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) who underwent LAGB, RYGB, or SG between 2008 and 2011 in the surgical departments of seven different Korean tertiary medical centers. Patients aged 17 years old or less were excluded. Patients were categorized into three groups depending on the surgical procedure: LAGB (n=72), RYGB (n=73), and SG (n=116). The ethics review boards of the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency and each participating hospital approved the study protocols.

Data collection

Baseline height, weight, blood pressures, and biochemical data were collected during the physical examination and laboratory assessments performed within a few days of bariatric surgery. Subsequent data were collected when the subjects made follow-up visits to the hospitals. Weight measurements at routine visits were averaged over three months to determine changes in weight at specific time points. For example, if patients measured their weight twice over three months from baseline, the weight at three months was recorded as the average value of the two measurements. Information on the patients' medical history before bariatric surgery was obtained through chart review. To investigate complications related with bariatric surgery, details of each event, onset date, and hospitalization were recorded.

Operative method

Details on each of the surgical bariatric procedures are provided hereafter. Briefly, for LAGB, a four- or five-port laparoscopic approach was used, depending on the surgeon's preference. The pars flaccida technique was applied for creation of the retrogastric tunnel, and either the LAP-BAND® (Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) or the Realize Band® (Johnson & Johnson, Neenah, WI, USA) was used. Several gastrogastric fixation sutures with nonabsorbable suture material were applied in all cases. The access port was exteriorized through a subcutaneous tunnel, and was placed by fixation to the rectus abdominis fascia. In all cases, intraoperative band filling was not performed, allowing at least four to eight weeks for capsule maturation around the band.

For RYGB, a six- or seven-port laparoscopic technique was used, and after creation of a small gastric pouch of less than 30 cc, a side-to-side gastrojejunostomy was constructed using a linear stapler. The measured Roux limb length was about 100 cm, and side-to-side jejunojejunostomy was performed using linear staplers. Potential areas for internal hernias were all suture-closed with nonabsorbable suture materials.

Finally, for SG, a five- or six-port laparoscopic technique was used. Omental dissection extended from about 5 cm proximal to the pylorus up to the angle of His; using a bougie with a diameter ranging from 36–40 French or a gastrofiberscope, several linear staples were applied, and a narrow sleeve was achieved. Suture reinforcement was performed or not, depending on the surgeon's preference.

Clinical effectiveness

Clinical effectiveness was investigated using four parameters: percentage of weight loss (%WL), percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL), percentage of excess BMI loss (%EBMIL), and absolute weight loss (AWL) from baseline. Percentage of WL was calculated by dividing changes in weight from baseline by baseline weight; %EWL was calculated by dividing weight changes from baseline by excess weight, which was obtained by subtracting ideal body weight from actual baseline weight. Ideal body weight was calculated as the height-adjusted weight depending on sex for a medium frame, according to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company tables (1983).7 Percentage of EBMIL was calculated by dividing BMI change from baseline by excess BMI, which was obtained by subtracting the ideal BMI (25 kg/m2) from the actual BMI. AWL from baseline was calculated by subtracting weight at a specific time point from weight at baseline.

Remission from comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, was investigated over time. In most cases, the management and follow-up of these comorbidities was usually performed by internists or primary care physicians, not by bariatric surgeons. Using the following definitions of concomitant diseases, prevalence before and improvement after bariatric surgery were investigated objectively. Diabetes was defined as the use of antidiabetic medications, fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥126 mg/dL, or a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level ≥6.5%. Hypertension was defined as the use of antihypertensive medications, systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg. Dyslipidemia was defined as the use of cholesterol-lowering medications, total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL, or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥160 mg/dL. Remission was defined as the patient being off medication and having laboratory/measurement values below the diagnostic criteria.

Safety assessment

Safety assessment was performed by collecting clinical information at two time points: within 30 days and after 30 days from bariatric surgery. Within 30 days, any occurrence of specific complications was noted, including deep vein thrombosis, venous thromboembolism, tracheal reintubation, performance of interventional endoscopic procedure for control of luminal bleeding, dilatation of strictures, air reduction in a kinked gastric tube, tracheostomy placement, percutaneous drain placement, anastomotic complication (e.g., leak, obstruction), bowel obstruction, incisional hernia, band slippage, gastric perforation, port/tubing system complication, pouch dilatation, or pneumonia. After 30 days, any occurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease, nausea/vomiting, internal hernia, gastric prolapse, band erosion, band removal, anastomotic stenosis, gallbladder stone, or marginal ulcer was also recorded. If patients reported other complications, they were specified in detail.

Statistical analysis

We summarized the patient characteristics and used analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables to investigate differences in baseline characteristics among the three groups. Changes in %WL, %EWL, %EBMIL, and AWL were summarized at 0 (baseline), 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months, and 95% confidence intervals were also calculated. ANOVA was used for the statistical testing of outcomes among the three groups at each time point. To reduce data entry error, two people independently input data into the data collection forms, which were developed using Microsoft Access software (2007). Subsequently, the accuracy of the inputted data was checked with SAS and corrected. Statistical data analysis was conducted with SAS software (9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

The characteristics of the 261 patients included in this study are presented in Table 1. The median follow-up period ranged from 6.3 to 11.6 months. BMI was similar among the three groups. Female sex was predominant in all three groups. The mean age was slightly higher in the RYGB group. The prevalences of hypertension and diabetes were higher in the RYGB group.

Table 1. Demographics.

| LAGB (n=72) | RYGB (n=73) | SG (n=116) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Follow up (days) | |||||||

| Median | 347 | 209 | 190 | 0.0005 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| Mean±SD | 38.9±5.4 | 39.0±6.9 | 39.1±6.2 | 0.9259 | |||

| 30≤BMI<35 | 19 | 26.4 | 23 | 31.5 | 32 | 27.6 | 0.9206 |

| 35≤BMI<40 | 25 | 34.7 | 26 | 35.6 | 44 | 37.9 | |

| BMI≥40 | 28 | 38.9 | 24 | 32.9 | 40 | 34.5 | |

| Sex | 0.9026 | ||||||

| Male | 17 | 23.6 | 17 | 23.3 | 30 | 25.9 | |

| Female | 55 | 76.4 | 56 | 76.7 | 86 | 74.1 | |

| Age (yrs) | |||||||

| Mean±SD | 33.6±10.3 | 39.1±11.1 | 35.0±10.4 | 0.0046 | |||

| Concomitant disease | |||||||

| Hypertension | 37 | 51.4 | 47 | 64.4 | 62 | 53.4 | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 29 | 40.3 | 40 | 54.8 | 56 | 48.3 | 0.1802 |

| Diabetes | 15 | 20.8 | 44 | 60.3 | 43 | 37.1 | <0.0001 |

LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; BMI, body mass index.

Weight-loss outcomes

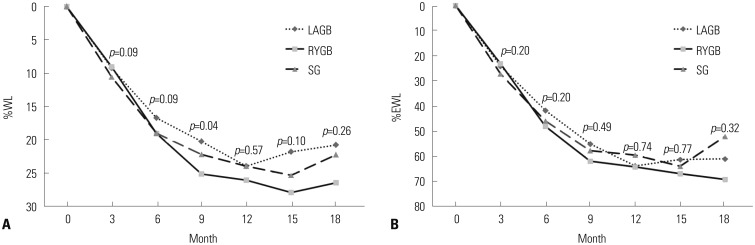

Changes in %WL, %EWL, %EBMIL, and AWL are listed in Table 2, and presented graphically in Fig. 1. Patients who underwent RYGB showed a tendency towards greater weight loss than those who underwent SG or LAGB; the difference was statistically significant only at a few time points. The %WL was significant at 9 months (RYGB vs. LAGB), and AWL was significant at 6, 9, and 15 months (RYGB vs. LAGB). The mean %EWL at the last follow-up (18 months) was 52.1% for SG, 61.0% for LAGB, and 69.2% for RYGB.

Table 2. Weight Change from Baseline.

| Time (month) | LAGB | RYGB | SG | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | n | Mean | n | Mean | |||

| %WL | 3 | 61 | 9.3 | 65 | 9.1 | 79 | 10.6 | 0.090 |

| 6 | 49 | 16.8 | 52 | 19.1 | 60 | 19.1 | 0.090 | |

| 9 | 39 | 20.3 | 36 | 25.2 | 36 | 22.2 | 0.042 | |

| 12 | 33 | 24.0 | 27 | 26.1 | 24 | 24.0 | 0.572 | |

| 15 | 20 | 21.9 | 24 | 28.0 | 25 | 25.4 | 0.099 | |

| 18 | 17 | 20.8 | 15 | 26.6 | 12 | 22.3 | 0.256 | |

| AWL | 3 | 61 | 9.9 | 65 | 9.8 | 79 | 11.5 | 0.115 |

| 6 | 48 | 17.5 | 52 | 20.9 | 60 | 21.3 | 0.041 | |

| 9 | 40 | 21.1 | 36 | 28.6 | 36 | 24.2 | 0.009 | |

| 12 | 33 | 25.2 | 27 | 29.0 | 24 | 26.0 | 0.413 | |

| 15 | 20 | 22.9 | 24 | 33.7 | 25 | 27.3 | 0.049 | |

| 18 | 17 | 20.8 | 15 | 29.3 | 12 | 26.8 | 0.215 | |

| %EWL | 3 | 61 | 24.1 | 65 | 23.2 | 79 | 27.2 | 0.208 |

| 6 | 48 | 41.8 | 52 | 48.1 | 60 | 45.9 | 0.209 | |

| 9 | 40 | 55.0 | 36 | 62.0 | 36 | 57.8 | 0.493 | |

| 12 | 33 | 63.9 | 27 | 64.3 | 24 | 59.6 | 0.742 | |

| 15 | 20 | 61.3 | 24 | 67.0 | 25 | 63.9 | 0.778 | |

| 18 | 17 | 61.0 | 15 | 69.3 | 12 | 52.1 | 0.325 | |

| %EBMIL | 3 | 61 | 29.9 | 65 | 28.3 | 79 | 33.2 | 0.302 |

| 6 | 48 | 51.1 | 52 | 58.6 | 60 | 54.9 | 0.321 | |

| 9 | 40 | 68.2 | 36 | 75.6 | 36 | 71.6 | 0.664 | |

| 12 | 33 | 79.1 | 27 | 78.6 | 24 | 70.9 | 0.608 | |

| 15 | 20 | 78.6 | 24 | 81.4 | 25 | 77.7 | 0.942 | |

| 18 | 17 | 77.2 | 15 | 87.0 | 12 | 61.4 | 0.300 | |

LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; %WL, percentage of weight loss; %EWL, percentage of excess weight loss; %EBMIL, percentage of excess body mass index loss; AWL, absolute weight loss.

Fig. 1. (A) Comparison of percentage of weight loss (%WL) over an 18-month follow-up. (B) Comparison of percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL) over an 18-month follow-up. %WL, percentage of weight loss; %EWL, percentage of excess weight loss; LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

Resolution of comorbidities

The prevalence of dyslipidemia was similar among the three groups before surgery. Meanwhile, diabetes and hypertension were more prevalent in the RYGB group, followed by SG. Remission from all concomitant diseases (diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) was more frequent in those who underwent RYGB (Table 3). While 65.9%, 63.6%, and 100% of patients showed remission from diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, respectively, in the RYGB group, remission rates were lower in the SG group (30.2%, 14.3%, and 73.7%) and the LAGB group (40%, 34.8%, and 66.7%). Laboratory measurements, including FBG and HbA1c, improved significantly from baseline values in the RYGB and SG groups.

Table 3. Remission from Concomitant Diseases.

| LAGB (n=72) | RYGB (n=73) | SG (n=116) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Diabetes | |||||||

| Prevalence | 15/72 | 20.8 | 44/73 | 60.3 | 43/116 | 37.1 | <0.0001 |

| Remission | 6/15 | 40 | 29/44 | 65.9 | 13/43 | 30.2 | 0.035 |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| Prevalence | 38/72 | 52.8 | 49/73 | 67.1 | 62/116 | 53.4 | 0.124 |

| Remission | 8/23 | 34.8 | 28/44 | 63.6 | 4/28 | 14.3 | 0.005 |

| Dyslipidemia | |||||||

| Prevalence | 26/72 | 36.1 | 29/73 | 39.7 | 44/116 | 37.9 | 0.904 |

| Remission | 10/15 | 66.7 | 28/28 | 100 | 14/19 | 73.7 | 0.006 |

LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

Complications

Early complications (within 30 days from surgery) occurred in 26 patients (9.9%), accounting for 12.5% of the LAGB, 12.3% of the RYGB, and 6.9% of the SG, while complications later than 30 days from surgery occurred in 32 patients (12.3%), representing 22.2% of the LAGB, 12.3% of the RYGB, and 6% of the SG (Table 4). The most frequent complication within 30 days from bariatric surgery was surgical site infection, followed by pneumonia/atelectasis. One patient who had undergone RYGB underwent reoperation because of small bowel obstruction. Other complications included leakage, bleeding, kinking of the gastric sleeve, stoma obstruction, rhabdomyolysis, band slippage, access port complications, diarrhea, and reflux symptoms. Complications at more than 30 days after surgery were more common in the LAGB group, although this difference was not statistically significant. Late band complications were mainly due to occurrence of port leak/revision and band erosion/removal. Five bands (6.9%) needed to be removed because of band erosion, access port infection, or band leakage. Other late complications included cholecystitis, internal hernia, intestinal perforation, wound dehiscence, and access port problems. Details on complications by type of surgery are described in Table 5. Some patients had more than one complication. There was one death (1/261=0.38%) due to aspiration pneumonia within 30 days from surgery in a patient who underwent RYGB. The other groups recorded no mortality.

Table 4. Postoperative Complication Rate.

| LAGB (n=72) | RYGB (n=73) | SG (n=116) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | No. of patients | No. of patients | |

| Total | 21 (29.2%) | 16 (21.9%) | 14 (12.1%) |

| Within 30 PODs | 9 (12.5%) | 9 (12.3%)* | 8 (6.9%) |

| After POD 30 | 16 (22.2%) | 9 (12.3%) | 7 (6.0%) |

LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; POD, postoperative day.

*Including one death.

Table 5. Details of Surgical Complications by Type of Surgery.

| LAGB | RYGB | SG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events | No. of events | No. of events | |

| Within 30 PODs | |||

| Fever/leakage | 1 | ||

| Pneumonia | 1 | ||

| Port/tubing complication | 1 | ||

| Rhabdomyolysis | 1 | ||

| Slippage | 1 | ||

| Stoma obstruction | 1 | ||

| Wound complication | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Atelectasis | 2 | ||

| Bleeding | 1 | ||

| Bowel obstruction* | 2 | ||

| Diarrhea | 1 | ||

| Aspiration pneumonia† | 1 | ||

| GERD | 1 | ||

| Kinking | 2 | ||

| Leakage | 1 | ||

| After POD 30 | |||

| Pneumonia | 1 | ||

| Port flip | 2 | ||

| Port flip/port revision | 1 | ||

| Port infection/band removal‡ | 1 | ||

| Port infection/port revision | 2 | ||

| Port leak/port revision | 1 | ||

| Band erosion/band removal‡ | 3 | ||

| Band leakage/band removal‡ | 1 | ||

| Slippage | 4 | ||

| GERD | 1 | 3 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 | 1 | |

| Dizziness | 1 | ||

| Hypoglycemia | 1 | ||

| Iron deficiency anemia | 1 | 1 | |

| Gallbladder stone | 1 | 1 | |

| Depression | 1 | ||

| Hair loss | 1 | ||

| Internal hernia§ | 1 | ||

| Intestinal perforation§ | 1 | ||

| Mallory-Weiss syndrome | 1 | ||

| Incisional hernia* | 2 |

LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; POD, postoperative day; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

*One patient was reoperated, †Died, ‡Band removed, §Reoperated.

DISCUSSION

This is the first Korean national study in which several academic institutions participated and pooled their data on bariatric surgery to compare clinical outcomes among different bariatric procedures (LAGB, RYGB, and SG). In our previous study, we showed that bariatric surgery was more effective than conventional medical treatment for obese patients in terms of weight-loss and improvement/resolution of comorbidities.8 In this multicenter study, our intention was to analyze the comparative bariatric outcomes among different weight loss procedures.

Bariatric surgery was first performed in Korea in January 2003, when the first laparoscopic SG was performed,9 followed later in the same year by laparoscopic RYGB, mini-gastric bypass, and vertical banded gastroplasty. In 2004, the first LAGB procedure was performed. By 2009, LAGB was the most popular bariatric procedure in Korea (68%), followed by RYGB (16%), SG (5.5%), and mini-gastric bypass (3%).6 This is an interesting phenomenon, since LAGB is decreasing in popularity worldwide in favor of other procedures.4 One possible reason is the less invasive nature of the LAGB procedure and the reluctance of Korean patients to undergo "major" surgery.

Many papers have compared surgical outcomes between different bariatric procedures; however, the conclusions were not categorical and sometimes conflicted. Chapman, et al.10 compared LAGB with vertical banded gastroplasty and RYGB, concluding that LAGB was superior to the other procedures in terms of safety and weight-loss outcome, at least after 4 years of follow-up. However, a cohort study that compared RYGB with LAGB in matched patients and followed them for 3 years showed superior weight loss and comorbidity reduction in the RYGB group.11 In a multicenter study that compared RYGB with SG, RYGB was associated with greater morbidity; however, weight loss was comparable at 6, 12, and 18 months, and remission of type 2 diabetes was more frequent.12 Given the increasing popularity of SG over LAGB as a restrictive procedure, one interesting study by Chakravarty, et al.13 compared LAGB with RYGB, vertical banded gastroplasty, and SG. In this systematic review of randomized controlled trials, the authors concluded that LAGB was not the most effective bariatric procedure to reduce weight, compared with the other procedures; nevertheless, it was associated with fewer early complications, as well as a shorter operative time and shorter length of hospital stay.

In the current study, although patients who underwent RYGB showed a tendency to have greater %WL, compared with those who underwent SG and LAGB, at 6 months postoperation; thereafter, the difference became statistically significant only at 9 months. The percentage of EWL was similar for the three procedures. In terms of AWL, RYGB demonstrated better outcomes only at 6, 9, and 15 postoperative months. As this study was not prospective, this marginal difference in weight loss may have been due to the heterogeneous population group and inter-institutional differences in patient management protocols. Moreover, the follow-up period of only 18 months was quite short. We may speculate that the weight-loss outcome might have been more pronounced in favor of RYGB and SG over a longer follow-up period. Indeed, a systematic review of randomized trials comparing SG, RYGB, and LAGB has shown a trend toward a better weight-loss outcome with RYGB (62.1–94.4%), compared to SG (49–81%) and LAGB (28.7–48%), over a follow-up period of up to 3 years.14

We demonstrated an effective resolution of comorbidities after bariatric procedures. RYGB, in particular, showed significantly better outcomes than LAGB and SG in regards resolution of diabetes and dyslipidemia. These results are consistent with those from other studies that analyzed the resolution of comorbidities after different operations.15 However, since the prevalence of comorbidities was different among groups, it would be difficult to make a direct comparison and determine which procedure was superior in this respect.

Whereas complications from LAGB occurring more than 30 days from surgery were almost double those occurring within 30 days, the complication rates in the RYGB and SG groups were similar for both time periods. This finding is in accordance with the findings from another study, in which LAGB was associated with more long-term complications, including band erosion, pouch dilatation, intractable reflux symptoms, and band removals.16 However, we must take into consideration that the LAGB group had a longer mean follow-up time, which may have influenced the increased complication rate.

In our study, one death was observed in the RYGB group. A multi-institutional study carried out by the American College of Surgeons, which compared LAGB, SG, and RYGB based on prospective longitudinal data, showed 30-day mortality rates of 0.05%, 0.11%, and 0.14%, respectively, suggesting that the surgical risk of bariatric procedures is highest for RYGB, followed by SG and LAGB.5

This study had several limitations that should be taken into consideration. First, the patient population was not homogenous, as those who underwent RYGB had more comorbidities. Second, the surgeons participating in this study had varying levels of bariatric surgical experience. Third, this was not a prospective study, but a retrospective cohort study with a limited follow-up period. Particularly, the total numbers of patients followed up was 84 (32.1%) at postoperative 12 months and 44 (16.8%) at postoperative 18 months; therefore, the statistical power of the study results is limited. Finally, there were noticeable inter-institutional differences in the management of bariatric patients. Nonetheless, the significance of this paper is that it is the first multi-institutional national study in which most major centers in Korea participated.

To conclude, this study demonstrates that all three bariatric procedures were comparably effective in terms of weight loss, with quite effective resolution of comorbidities. Complications were more severe in the RYGB group; however, LAGB was associated with a higher rate of late complications. Our results suggest that all three procedures are viable alternatives for patients whose obesity problem is not amenable to medical treatment. A prospective randomized study would be desirable to determine the relative superiorities of each of the bariatric procedures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was completed as part of the health technology assessment report (Project no. NA2011-003) funded by the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency (NECA) in South Korea.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health and Welfare. Ministry of Health and Welfare statistical year book. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2013. pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, Ahlin S, Andersson-Assarsson J, Anveden Å, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with long-term remission of type 2 diabetes and with microvascular and macrovascular complications. JAMA. 2014;311:2297–2304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg. 2013;23:427–436. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, Ko CY, Cohen ME, Merkow RP, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;254:410–420. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c9dac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SK. Current status of laparoscopic metabolic/bariatric surgery in Korea. J Minim Invasive Surg. 2015;18:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.1983 metropolitan height and weight tables. Stat Bull Metrop Life Found. 1983;64:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heo YS, Park JM, Kim YJ, Kim SM, Park DJ, Lee SK, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional therapy in obese Korea patients: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;83:335–342. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2012.83.6.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon Han S, Kim WW, Oh JH. Results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) at 1 year in morbidly obese Korean patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1469–1475. doi: 10.1381/096089205774859227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman AE, Kiroff G, Game P, Foster B, O'Brien P, Ham J, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the treatment of obesity: a systematic literature review. Surgery. 2004;135:326–351. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(03)00392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cottam DR, Atkinson J, Anderson A, Grace B, Fisher B. A case-controlled matched-pair cohort study of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and Lap-Band patients in a single US center with three-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2006;16:534–540. doi: 10.1381/096089206776944913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chouillard EK, Karaa A, Elkhoury M, Greco VJ Intercontinental Society of Natural Orifice, Endoscopic, and Laparoscopic Surgery (i-NOELS) Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: case-control study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakravarty PD, McLaughlin E, Whittaker D, Byrne E, Cowan E, Xu K, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) with other bariatric procedures; a systematic review of the randomised controlled trials. Surgeon. 2012;10:172–182. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Guarino S, Cirocchi R, Scalercio V, Noya G, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy compared with other bariatric surgical procedures: a systematic review of randomized trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:816–829. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campos GM, Rabl C, Roll GR, Peeva S, Prado K, Smith J, et al. Better weight loss, resolution of diabetes, and quality of life for laparoscopic gastric bypass vs banding: results of a 2-cohort pair-matched study. Arch Surg. 2011;146:149–155. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angrisani L, Cutolo PP, Formisano G, Nosso G, Vitolo G. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year results of a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]