Abstract

It is now clear that women doctors will soon make up the majority of the medical workforce. Research shows that women often prefer part time and flexible working, and are inclined to favour some specialist fields over others. Although these facts are widely known, as yet it appears that little account has been taken of their economic and organisational consequences. All doctors require sound careers advice, but women doctors reported that this is often poor or inconsistent. Women's preference for flexible working at certain stages of their careers could be a major advantage in health service planning; models need to be developed that recognise women's willingness to work in new ways. Although women are under-represented in positions of national leadership, there is no evidence to suggest that they are disadvantaged in their endeavours, or unwilling to deliver the commitment necessary. However, they may need timely advice and encouragement to reach their full potential.

Key Words: education, training, women, workforce

Five recent reports on women and medicine have highlighted the need to take a critical look at the implications of the increasing numbers of women taking up medicine, and the opportunities and choices they have once qualified.1–5 Women doctors will soon be the majority, and whatever the factors are that determine their choices, research conducted by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) shows that women prefer part-time and flexible working particularly in the early years following qualification1; that women who always work full time have very similar career trajectories to men6; that women prefer to train in some specialist fields more than in others (including general practice); and that, by and large, they feature less prominently in what the medical profession regards as ‘leadership’ positions – certainly in numbers lower than their representation in the medical workforce would suggest was equitable. In the context of this paper, ‘leadership’ denotes duties and responsibilities additional to those normally associated with consultant or principal in general practice posts. For example, officer positions in faculties and royal colleges; medical directors or chief executives in trusts and primary care trusts; senior management positions in universities and research institutions, etc. These factors will have considerable impact on the way medicine is planned and delivered for the next few decades.

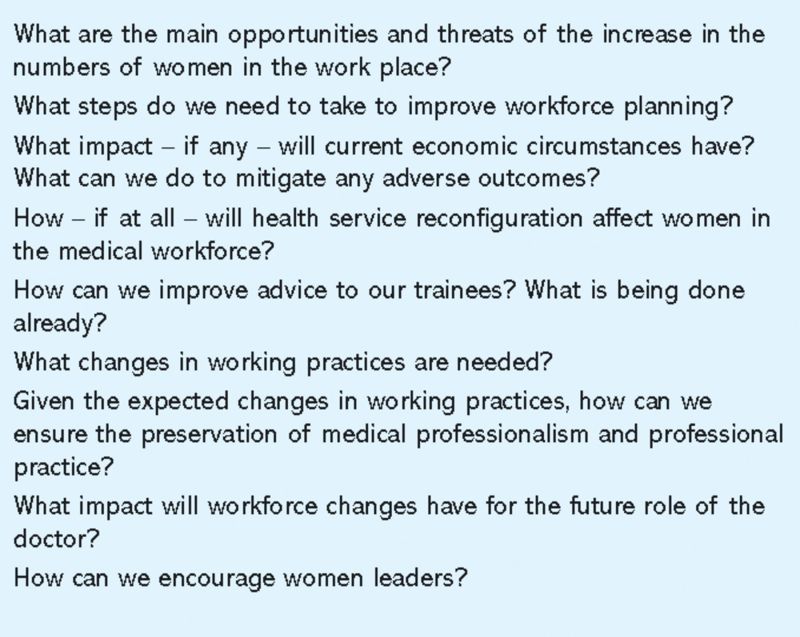

In November 2009, the RCP brought together the authors and researchers involved in the production of the five previously mentioned reports,1–5 together with others with an interest in the topic to establish consensus on the key issues, and to reach conclusions on how these might be addressed. The five reports cited have all made recommendations in relation to women and their roles in the medical profession, but there remains a concern that not enough has changed, and that it is essential to take account of the increasing female share of the profession when planning the future workforce. The seminar was facilitated around a series of core questions and prompts derived from the five reports as listed in Box 1.

Box 1. Core questions derived from the five reports.

The meeting was held under the Chatham House Rule (participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speakers(s), nor that of any other participants, may be revealed) and discussion was recorded and transcribed. The points set out in this commentary reflect the views of seminar participants and draw on dialogue to emphasise points made.

What was discussed?

The main issues which emerged from the discussion related to:

careers advice

part-time working

childcare needs

economic challenges

women in clinical academia

clinical leadership.

Providing high-quality care for patients is at the heart of what motivates doctors. In this, women and men are similar.7,8 The seminar participants agreed that future challenges in providing a fully trained, fully engaged and competent medical workforce transcend the gender divide. The discussion is very definitely moving from one exclusively of ‘what can we do for women’ to one of ‘these are the workforce challenges, how can the medical community respond positively’. If women doctors have particular needs at certain stages of their careers now, it is anticipated that in the future male doctors will be likely, in increasing numbers, to ask for similar consideration. Therefore, framing the argument simply in terms of women is the wrong focus. Going forward a gender-independent solution for medical education, medical training, and medical staffing has to be devised that continues to deliver the highest standards of patient care in an evolving healthcare system; a solution that addresses the needs of doctors, the public and the service. Although there has been a lot of discussion of these issues over the last decade disappointingly not much has changed, although a recent report has offered some suggestions.3

Careers advice

A key component of providing the workforce necessary to deliver high standards of care to patients is advice to those at the early stages of their careers. Information about career options and the likelihood of success in particular specialties or geographical regions is key to decision making: ‘The main thing is having a realistic idea of what the options are and this is important at an early stage – I need to know what the options are before I make a decision’.

This applies whether a young doctor is contemplating full- or part-time work, with or without children. Speaking to a senior female colleague is considered one of the most helpful ways for female trainees to obtain the information they need, but too often advice is poor and inconsistent:

‘Advice to trainees can be hit and miss. It needs to be standardised and the approach needs to come from above, not just the things that individuals do in a bottom up way’

‘A difficulty is that advice given in one deanery may be wrong for another, and this becomes very difficult because people do move around even if this is not planned. If we could get uniformity that would be a step forward’.

Current policy is to move some aspects of healthcare out of hospitals and into the community. Not only is it imperative, therefore, that medical students and trainees are provided with adequate information about the inherent characteristics of their chosen specialty, but also about the implications of that choice with respect to the changes that are anticipated in the way healthcare may be delivered in the future.

Part-time working

There is no current shortage of training posts but ‘unless we can get them [trainees] through training they will not be consultants at the end of it’. Supporting a young doctor through training is paramount: once this is provided the ‘part-time’ element becomes less of an issue as it is easier to work part time at consultant or general practice partner level.

More flexibility in training programmes would allow those with childcare responsibilities to achieve the competencies necessary to gain a Certificate of Completion of Training, and would result in fewer female doctors with children opting for staff and associate specialist grade posts, or leaving medicine altogether: ‘All you need to do is to ensure that training is of the same duration, level and quality in the whole programme as for a full-timer. It is achieving the competencies that matters’. Further: ‘Once you become a consultant you can do part time work and men do that in the same percentage as women – our problem is for women trainees getting their education’.

Given a uniform quality of training, the key issue is to get trainees through training, with flexibility as the guiding principle:

I would like to see a review of medical education funding so that flexible or part time trainees are fully funded from education funds and that then gives them flexibility to choose where they want to go that fits in with the rest of their lives.

Trainees do not want to cause problems for their trainers or their deaneries: ‘I want to be able to fit in in a way that is productive for the service and not cost more money’. Providing examples of options for part-time and flexible training, or solutions for when a situation changes unexpectedly, would greatly help both sides.

Part-time working is a well-established fact in many professions. What is lagging behind in medicine is its ‘normalisation’ and a willingness to capitalise on advantages that part-time working bring. For a trainee:

If I had the opportunity I would be in a better position to provide alternative hours which may actually be an opportunity for work force planners as I am here as a resource.

But demands need to be realistic:

If you are a working mother and you are asked to do something and you have adequate advance notice you will do it. If you are asked to do something immediately there are issues. Expectations of how quickly trainees can respond (outside the emergency situation) needs to be adjusted.

Notwithstanding this debate revealed that many patients prefer to see the same doctor – an issue which flexible working patterns do not always adequately address.

Child care

The issue of how and from where childcare is provided, and the part it plays in enabling women to train and remain in work, remains a central issue. The seminar discussion returned frequently to this problem:

I have to acknowledge that this new man who wants to stay at home with his children is a rare bird, but no doubt there will be more of them. But in practice we realise that it is women who take child and elder care responsibilities.

No matter how understanding and accommodating partners, parents, close family members and friends are prepared to be, it cannot replace an acceptance at national level that childcare provision is one of the critical aspects that enable women to work. In the words of one seminar participant ‘you will not get the best out of women throughout all careers unless you make childcare possible’. Increasingly this responsibility will extend to the care of other vulnerable family members, and to the careers of men.

Any discrepancy noted in the ‘progress’ of some women compared to others is often attributed to whether or not a woman worked part or full time, which is usually as a result of their caring responsibilities outside the work place:

The story is that women who always work full time have very similar career trajectories to men and the issue for women not progressing is the obvious one, it is part time working.

Economic challenges

Delivering high-quality care while at the same time providing suitable part-time and flexible training and working opportunities, together with an acknowledgement of the understandable desire of doctors to maintain a sensible work–life balance, is an issue that is likely increasingly to confront both employers and doctors. Accommodating individual need will inevitably bring pressure on the service and on other doctors. There is tension between providing the best quality patient care, providing a working environment that encourages and supports men and women who want to work flexibly, and the current financial climate which demands increasing efficiencies in the NHS:

The essence of the dilemma that the profession is facing is that all doctors subscribe to the notion that the guiding principle is optimal patient care – but this has workforce design tradeoffs.

The service capacity required to deliver the kind of patient care that doctors are committed to may no longer be compatible with what is affordable. Demand is no longer about the needs of the male and female medical workforce but about what employers are willing to pay for.

Part-time work may constitute an unwelcome cost pressure on the service at a time of economic difficulty: ‘part time work is a lot more expensive and is a lower return on investment’. In addition it brings a ‘huge amount of organisational complexity’, with job shares creating ‘enormous matching difficulties which should not be underestimated’.

It is often quoted that trained specialists provide efficient and more cost-effective patient care. Any reduction in the quality and content of specialist training should therefore be resisted at all costs. In a time of financial constraint high quality cost-effective care provided by trained specialists makes sound economic sense.

Women in clinical academia

The crisis in recruitment and retention in academic medicine and dentistry for men and women is described eloquently in the Medical Schools Council (MSC) 2007 report Women in clinical academia.4 There is a reduction in the number of posts that are filled in academic medicine which applies across the board, although the particular situation of women within this is well recognised. The MSC research showed a poor understanding among undergraduates of what is meant by ‘clinical academia’, evidence of discrimination in some branches of medicine, and a paucity of mentorship. It appears that academia is particularly difficult for women to take part in and sustain on a part-time or flexible basis, but something which is vital to overcome for the future good of the profession. The competing demands of research, teaching and clinical work are difficult for all clinical academics, and it is often not possible to achieve excellence in all three:

‘Academe is a microcosm of the issues facing women in medicine and we have to recognise that academic medicine and the teachers and researchers in our medical schools and in our medical community are vital for the development of the doctors of the future and for healthcare of the future’

‘Attracting women into academic medicine is the area that concerns me because that is the area that we can really deliver something into the economy’.

Further discussion emphasised the consequences of the poor representation of women in academic medicine: ‘because women are under-represented in academic medicine that is why women are under-represented in medical leadership’.

Leadership

The issue of how and in what numbers women attain ‘leadership’ positions remains contentious. Women are reaching consultant status in increasing numbers, but are perhaps not yet reaching parity at the very highest levels. When they put themselves forward there is no evidence that women are disadvantaged in their attainment of recognition in the form of clinical excellence awards. But although women will come to leadership roles later in their careers and that it is not an ‘all or nothing’ situation, one participant commented: ‘I do not see the support systems in place to permit women to get the confidence to push to get themselves to the top, at whatever time they come back in’.

Examples of good practice exist – notably schemes set up by the Department of Health, and the RCP MSc in medical leadership, however:

The amount we invest in our current work force in terms of leadership training and development is miniscule. It seems extraordinary given that managers are now recognising that change will not happen unless doctors lead it.

Simply creating opportunities for young people, however, is not enough:

Medicine is different from many professions in that the authority comes not only from training but from the regard that one is held in. Putting a lot of young people into leadership roles does not always work – those who will inspire the followers need to be held in high regard for their professional skills as well as their people management and visionary skills. This is a difficult balance.

Leadership is not an easy ride: ‘Medical professionalism will not exist on its own: the top 200 jobs in any profession require total commitment’. Only doctors themselves can determine where that commitment will come from. Women can deliver it, but they need to be very determined and may need some help along the way.

Final thoughts

With increasing numbers of women doctors entering all specialties the changing demographic of the medical profession is inevitable. The seminar identified a number of issues, the resolution of which will contribute to the quality of patient care by providing a basis for the efficient and equitable delivery of healthcare in the future.

Effective careers advice is an essential component of ensuring that we get the best doctors into the best and most appropriate jobs. The ‘normalisation’ of part-time working for men and women will allow more doctors to achieve their potential in clinical medicine at the same time as providing care for others, and developing other career opportunities in areas such as clinical leadership. Further debate is needed to achieve consensus on how best to plan and organise child and elder care for those doctors with family responsibilities.

There is an urgent need for the Department of Health to focus on collating an accurate longitudinal data set to support workforce planning, and to consider strategies for reconfiguration of the trainee workforce with minimal disruption if the predictions made prove to be inaccurate. A realistic estimate of the costs of less than full-time training should be balanced against the need to keep women contributing in the medical workplace, and not waste the considerable investment of getting them there.

Women and men in academic medicine would be greatly supported if policy makers would look closely at the conflicts between achieving excellence in research and teaching together with a clinical career. Pragmatic approaches to support the clinical academics of the future, such as separate teaching and research career tracks, would make the achievement of academic excellence more likely.

A continued focus on the development of women and men as future clinical leaders is imperative if the health service is to get the leadership quality it needs.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians Women and medicine: The future. London: RCP, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.British Medical Association Women in academic medicine: challenges and issues. London: BMA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health Women doctors: making a difference. London: DH, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medical Schools Council Women in clinical academia. London: MSC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medical Women's Federation Making part time work. London: Medical Women's Federation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldacre MJ, Davidson JM, Lambert TW. Retention in the British National Health Service of medical graduates trained in Britain: cohort studies.. BMJ 2009;338:b1977. 10.1136/bmj.b1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKinstry B. Are there too many female medical graduates? Yes. BMJ 2008;336:748. 10.1136/bmj.39505.491065.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dacre J. Are there too many female medical graduates? No. BMJ 2008;336:749. 10.1136/bmj.39505.566701.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]