ABSTRACT

In response to the call from an international panel for ‘much needed rethinking’ about the goals and purposes of the education of healthcare professionals, we suggest that there must be an explicit account of the virtues and values that will inform healthcare practice in the 21st century. We propose that a renewed emphasis is needed on reviving the well-honed clinical skills and humanistic attributes in medicine as crucial for optimum affordable (and sustainable) care of individual patients. Analogous virtues should be linked to the quest for improving the health of whole populations, nationally and globally.

KEYWORDS: Education, virtues, clinical

Introduction

An international panel reporting on a vision of education for health professionals in the 21st century has called for ‘much needed rethinking’ about the goals and purposes of the education of healthcare professionals. The importance of ethics is noted in passing and values are mentioned several times in the report. However, the values that should be exemplified in health professional education are not explicated and there is no discussion of the type of ethics education relevant to 21st century healthcare.1

In our view, it is precisely the values that the best physicians exemplify in practice that create the ground for their authority and legitimacy in the sphere of healthcare. Calling for physicians to be transformative leaders without explicit discussion of a desirable value base of their practice leaves this notion as an empty formalism. Furthermore, without reflection on which elements from the ethical traditions of medicine are worth retaining and reinforcing in future education, we risk transformation for its own sake, ungrounded in any telos of medicine.

We contribute to the debate on ‘the remoralisation of health professionals’ by providing some substantive input into thinking about health, the role of health systems, and the education of physicians in the 21st century, through a renewed elaboration of medicine's value base in two key domains of great social importance: individual care and global health.

Individual patient care

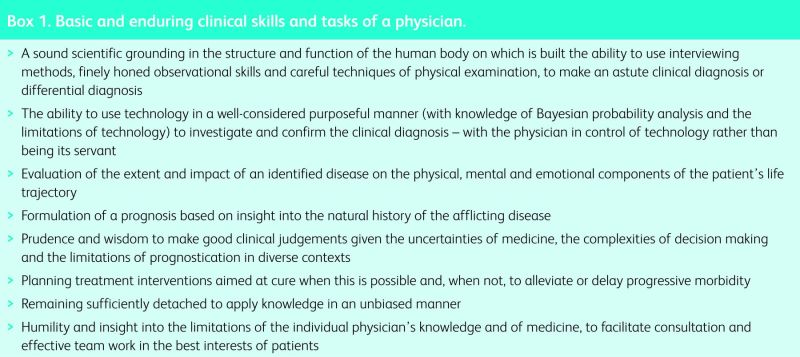

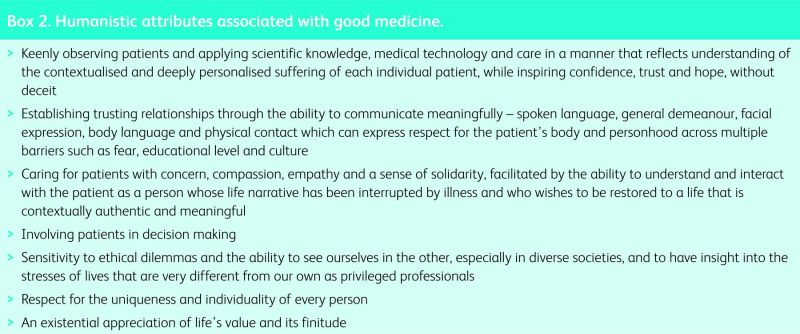

The forces shaping health and disease and that drive health needs and health practices in the 21st century are markedly different from those in the 20th century. Although such forces reflect contingent historical and cultural influences, we nevertheless contend that, at the level of care of individuals, there are timeless and essential scientific and clinical approaches and humanistic attributes required for effective and compassionate care. These do not play out in silos, but are as integrated as both sides of a coin (Boxes 1 and 2).

If 21st century physicians are to engage in transformative learning, be exemplary leaders and act as change agents, the qualities, characteristics and normative origins of these attributes should be clearly articulated, re-emphasised and defended as basic and enduring clinical skills/tasks of physicians.

Traditional concepts of medical ethics, centred on standards of professional competence and conduct, are broadly outlined by formal codes of practice. Professionals are expected to have integrity, be worthy of trust, be more concerned with caring for others than with making money and have a substantial commitment to their patients’ welfare.2 These attributes go beyond the ideas of mere competence and duties of healthcare outlined in the Physician Charter's ‘basic professionalism’3 to embrace a ‘higher professionalism’ underpinned by considerations of excellence and virtue.4

Radical changes in the discourse on medical ethics began in the 1960s and 1970s through a critical multidisciplinary and public perspective that supplemented (and to some extent eclipsed) the duties of physicians with patients’ rights. Bioethics has now become a more comprehensive field which includes legal and socioanthropological insights and consideration of ethical theories. Challenges posed to modern bioethics are that it is excessively focused on analysis, theory, narrow principles and individualism.5 Criticisms from feminist, multicultural and other social science perspectives have called for supplementation of the philosophical approach with an expanded emphasis on patient narratives of illness, the development of empathy and an understanding of the nature of the moral life in varied contexts.6

Box 1. Basic and enduring clinical skills and tasks of a physician.

Bioethics has also been criticised by human rights activists. Although both groups share values with regard to human dignity, their discourses and methods differ. The scope of bioethics is more comprehensive than human rights in embracing concepts of duties and virtue, empathy, compassion and communication skills that cannot be dealt with through a rights approach.7 However, the concept of rights is powerful and increasingly playing a role in medicine and advocacy for a right to healthcare. Additional concerns are that inadequate attention is being given to virtuous aspects of practice that are important in developing the sense of duty and excellence in caring for others. When combined with judgement and skill in developing rapport with patients as individuals, these make vital contributions to healing.

Virtues

Virtue theory with its long lineage in the western tradition focuses on the ideal traits of character that can be aspired to, encouraged and developed in life generally, and in medical education and practice specifically. These traits encompass both the cognitive/intellectual abilities (rigor and objectivity) and the ethical attributes of physicians (honesty, compassion, temperance) which derive from the habits of working practically and self-reflectively within one's professional field. They describe a mode of behaviour and character defined as commitment to excellence as the internal purpose of the professional role.2

Box 2. Humanistic attributes associated with good medicine.

The ethical and epistemological dimensions of virtues (related to the generation, evaluation, justification and application of knowledge in practice) can set norms to which clinicians could aspire. James Marcum has identified ‘reliabilist’ virtues that relate to the cognitive skills of a clinician in terms of the intellectual function and capacity to obtain relevant and appropriate knowledge in clinical care, and ‘responsibilist’ virtues characterised by intellectual curiosity, courage, honesty and humility. He argues that all these virtues must be associated with a ‘passionate desire to know the truth’ (love of knowledge) and the intellectual virtue of wisdom – both theoretical and practical.8 Marcum's recommendations for encouraging training in intellectual and ethical analyses resonate with the use of narratives and moral examples as a means of teaching ethics.6

We suggest that attention to virtue theory is a key element in the quest for transforming the education of health professionals, because it regards intellectual and moral attributes as inseparable aspects of physicians as agents engaged in everyday life. The strength of a virtue-based approach is that it recognises that such qualities and characteristics are evident in the practices of the best clinicians. Such virtues directly link in with the obligations of physicians to ‘know’ responsibly and act prudently on the basis of this knowledge. Virtue is thus more realistically applicable to teaching and role modelling than are more abstract formulations of rules and responsibilities. Taken together, these virtues constitute a set of integrated professional skills that can be cultivated and evaluated. Dedication to achieving excellence provides internal satisfaction for professionals and facilitates the achievement of high professional ideals. These virtues cement the trust that patients have in the physicians caring for them.

Regrettably, these desirable, integrated, professional virtues are in the process of attrition because of excessive reliance on and indiscriminate use of technology in medical care that is superspecialised, fragmented, depersonalised, bureaucratised and commodified.9 Changes in professional medical education, although necessary, cannot be seen as remotely sufficient in the quest to address many of the profoundly health-adverse issues raised in The Lancet report.1 Meeting the challenge of changing medical education should be associated with serious attempts to change the practice environment. This is a major social task, as explained by Fineberg.10 Both tasks could improve the effectiveness of clinicians as agents of change in the personal lives of individual patients, and within nations, to enhance equity and reduce healthcare costs.

We suggest that the required transformation needs both a deep understanding of the motivation and structure of the political economy of health within which healthcare delivery systems operate, and practical measures to rectify the most egregious controlling forces that adversely affect health and healthcare in practice.11 In the absence of attention to these forces ‘reforming’ medical education will serve merely as a smokescreen for the wider challenges that most either fail to see or choose to ignore at great loss for societies.

Population health

The Lancet commission report enshrines population health skills as necessary for the practice of healthcare in the 21st century.1 With regard to the health of whole populations (within nations and globally), we argue that to be truly transformative in a world characterised by widening disparities (with almost 50% of all people in the world lacking access to even the most basic healthcare and living greatly deprived lives under conditions of severe poverty), acknowledgement is required of the fact that the lives of geographically disparate people are more intimately interconnected than ever before. The central role of the global political economy in health cannot be ignored because it shapes the health of billions of people.11

If health professionals in the 21st century are to make transformative contributions to improved population health, practice and research will have to be informed by a broader range of skills, concepts and ideas which do not emerge easily from traditional bioethics, with its overarching focus on individuals. Such justifications can be found within our emerging understanding of public health, public health ethics, global health and global health ethics.12,13

Public health ethics is concerned with examining the tension between collective and individual goods, and evaluating arguments about how best to strike a balance between these conflicting perspectives. Although the focus on individual rights is vital and necessary for the wellbeing of individuals, this is not sufficient for the achievement of improved public health, as revealed from insights gleaned from the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic as a specific example.14

Much work is needed to convincingly articulate obligations to society and promote the virtuous strategies that could sustain and support effective healthcare systems within nations and globally.15,16 Given the major leap required to extend caring for individual patients to include promoting the health of whole populations nationally and globally, it is necessary to ask how all the elements necessary for the care of individuals could be imaginatively embodied in a system approach to healthcare provision that acknowledges (and attempts to rectify) the many adverse forces that profoundly influence the health of whole populations.17

Some years ago it was proposed that an impetus for improvements in global health, wellbeing and meaningful development could be provided through a transdisciplinary approach: global health ethics. It was envisaged that broadening the ethics discourse (beyond the microlevel of interpersonal relationships to include the ethics of institutions and ethical concerns over the nature of international relations and the global environment), together with promotion of several shared foundational values, could lead to implementation of transformational approaches.12 Others support our argument that solidarity is the most important value to consider if distant indignities, violations of human rights, inequities, deprivation of freedom, undemocratic regimes and disrespect for the environment are not to be ignored.18

If universalism and interdependence are acknowledged as tenets of global health, then their normative basis can be grounded in a form of cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitanism, similar to the virtue theory articulated previously, is an ethical perspective that dates back to antiquity, in particular to Stoic accounts regarding humans as citizens of the world. Cosmopolitanism has evolved over the centuries, but a common theme is that humans have affiliations with each other regardless of nation of birth, identity, family relationships, or political and religious allegiances. Rather than attempting to fully explain the tenets of cosmopolitanism to adjudicate between claims of moral and political cosmopolitanism, we have instead suggested that it may be valuable to start discussions concerning what we will term ‘cosmopolitan global health’. Cosmopolitan virtues (tolerance, curiosity, epistemic humility and generosity) help illuminate the types of qualities and characteristics of a global health citizen.19 Emphasis is placed on justice and the need to recognise and respond to the suffering of others. A cosmopolitan account is consistent with the virtue-based account articulated earlier, and could be propagated by practising clinicians through their support for humanitarian medical groups and work in health policy towards reducing health disparities. If those who are privileged could develop empathy for and solidarity with deprived fellow citizens within their local environments, constructive change towards developing a spirit of solidarity with fellow humans globally could be possible.12,18

A central role for educational systems in developing the character and values of children and adolescents for the 21st century would be to promote a notion of ‘global consciousness’ that enables us to identify more effectively with all within our own nations and across the world. Recognition of the broader national and global dimensions of health, and the inextricable linkages between health professionals and healthcare systems within what has been called a ‘medical industrial complex,’20 reinforces the notion that there are ethical considerations that extend beyond the physician–patient relationship.

Although many would argue that a concern for population health is not required by practising physicians, and should be left to public health practitioners, we believe otherwise. Providing insights into this perspective is essential if highly specialised, technologically dominated healthcare is not to be continually favoured through aggressive, corporate-controlled and rescue-oriented care systems – often at great (and unsustainable) expense, with only marginal benefits, great opportunity costs and neglect of broader population health considerations at national and global levels. The magnitude of the mindset shift required to move from hyperindividualism to individualism within community should be neither underestimated nor undervalued.21–23

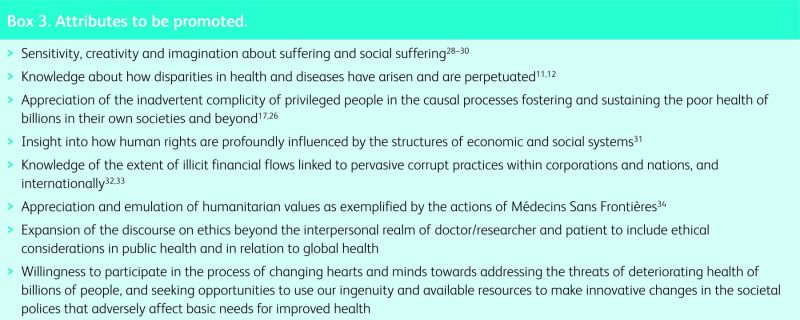

An ambitious programme would require the funding of multidisciplinary research and knowledge translation through a new series of grand challenges aimed at identifying the ways in which powerful global forces shape human wellbeing and population health, and designing studies to determine how best to counter and hopefully reverse such adverse social forces.24 The potential effectiveness of the grand challenges’ approach to scientific technical issues in medicine could be fruitfully emulated in the realm of the structure of social forces that affect population health. Becoming a transformative agent of change in global health requires much more than merely having knowledge of the current state of global health or propagating simplistic notions of human rights abuses, and many attributes need to be promoted (Box 3).

Challenges

We live in an increasingly interdependent world, in which the health of all is intertwined through a pervasively adverse global political economy that has over-commercialised healthcare, amplified frivolous consumption patterns and tipped the world into a state of entropy characterised by emerging infectious diseases and environmental threats.25 Failure to see health as a social goal for all allows for the ongoing commercialisation of medicine with endlessly rising costs, inefficiencies and widening disparities in health, which undermine both the enterprise of medicine and the peace and stability of national and global communities.

Box 3. Attributes to be promoted.

The immense challenge of sustaining medicine as a universally caring social and humanitarian institution, within nations and globally, requires the rethinking and -re-imagining of the skills and goals of medicine, and how these could be promoted and supported within sustainable societies. Improving global health will involve acknowledging that all lives are of value, regardless of wealth or educational level, and that we are all threatened and diminished by allowing billions of people to live miserable lives filled with preventable and unnecessary suffering. Pursuit of this agenda will require the participation of educational leaders in healthcare and many other professions.

Although much work needs to be done to achieve The Lancet commission's goals, it is arguable that intellectual and financial resources are available to begin to reverse adverse trends, reduce injustice and improve health for billions of people.26 Given the ubiquity of limited resources in relation to escalating demands, and the limits of life and current knowledge, it is necessary to acknowledge boundaries and set priorities with transparency and accountability as inevitable components of the quest for a good society.

A crucial step would be to make a concerted effort to enrich the medical curriculum with sufficient time and resources to teach the requisite reasoning skills to grapple with the complex sociological and ethical issues that face medical students in the new millennium, and to inculcate the types of desired virtues that we have outlined here.

Virtue theory, as applied locally to medical practice and globally to the care of individuals and health of whole populations, is a promising point of departure for a wider discussion on the way in which healthcare professionals could serve as transformative leaders in a cosmopolitan world.25 There must be an explicit account of the virtues and values that will inform healthcare practice in the 21st century.

Conclusions

We propose that a renewed emphasis is needed on reviving the well-honed clinical skills and humanistic attributes in medicine as crucial for optimum affordable (and sustainable) care of individual patients. Analogous virtues should be linked to the quest for improving the health of whole populations, nationally and globally. We acknowledge that there is no guarantee that reforming medical education through enhanced teaching of ethics, sociology, economics and the humanities generally will make practitioners behave more ethically, or in a more socially responsible manner. However, the hope is that sensitising students to the many complex ethical and social issues faced in healthcare, and providing them with insight into the role of moral reasoning in justifiably ranking potential solutions, may lead to improvements in attitudes and practices. Clearly good examples, shown by established clinicians and teachers at the bedside and by leaders who set institutional and national policies, could inspire emulation by new generations of health professionals.

Acknowledgement

Based, with permission from the publisher, on Benatar S, Upshur R. Virtue in medicine reconsidered: individual health and global health. Perspect Biol Med 2013;56:126–47.

References

- 1.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores A. Professional ideals. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medical Professionalism Project Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:243–6. (Simultaneous publication in Lancet 202;359:520–22.) 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swick HM, Bryan CS, Longo LD. Beyond the physician charter. Perspect Biol Med 2006;49:263–75. 10.1353/pbm.2006.0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox RC, Swazey J. Observing bioethics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195365559.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinman A. What really matters: Living a moral life amidst uncertainty and danger. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benatar D. Bioethics and health and human rights: A critical review. J Med Ethics 2006;32:17–20. 10.1136/jme.2005.011775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcum JA. The epistemically virtuous clinician. Theor Med Bioethics 2009;30:249–65. 10.1007/s11017-009-9109-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynn J. My mother's broken back: a fall into the quality chasm. Hastings Center Currents 2013:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fineberg HV. A successful and sustainable health system: How to get there from here. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1020–7. 10.1056/NEJMsa1114777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill S, Bakker IC. The global crisis and global health. In: Benatar S, Brock G. (eds), Global health and global health ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011;221–38. 10.1017/CBO9780511984792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benatar SR, Daar AS, Singer PA. Global health ethics: A rationale for mutual caring. In: Benatar S, Brock G. (eds), Global health and global health ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011;129–40. 10.1017/CBO9780511984792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson A, Verweij M. Ethics, prevention and public health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer P, Benatar SR, Bernstein P, et al. Ethics and SARS: Lessons from Toronto. BMJ 2003;327:1342–4. 10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKee M. Health systems and health. In: Benatar S, Brock G. (eds), Global health and global health ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011;63–73. 10.1017/CBO9780511984792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills A. Health care systems in low and middle-income countries. N Engl J Med 2014;370:552–7. 10.1056/NEJMra1110897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benatar SR. Moral imagination: the missing component in global health. PLOS Med 2005;2:e400. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto A, Upshur R. Global health ethics for students. Developing World Bioethics. 2009;9:1–10. 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00209.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Hooft S. Cosmopolitanism as a virtue. J Global Ethics 2007;3:303–15. 10.1080/17449620701728014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Relman AR. The new medical industrial complex. N Engl J Med 1980;303:963–70. 10.1056/NEJM198010233031703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benatar SR. Global health and human rights: Working with the 20th century legacy. Annual Human Rights Lecture. University of Alberta, May 2011. www.globaled.ualberta.ca/en/VisitingLectureshipinHumanRights/~/media/uaige/docs/BenatarLecture.pdf [Accessed 31 July 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birn A-E. Addressing the societal determinants of health: the key global health imperative. In: Benatar S, Brock G. (eds), Global health and global health ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011;37–52. 10.1017/CBO9780511984792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benatar SR. Global leadership, ethics and global health: The search for new paradigms. In: Gill S. (ed), The global crisis and the crisis of global leadership. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001;127–43. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benatar SR, Gill S, Bakker IC. Making progress in global health: the need for a new paradigm. Int Affairs 2009;85:347–71. 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2009.00797.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oreskes N, Conway EM. The collapse of Western civilization: A view from the future. Daedalus. 2013;142:40–58. 10.1162/DAED_a_00184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benatar SR. Needs, obligations & international relations for global health in 21st century. In: Coggon J, Gola S. (eds), Global health and international community. London: Bloomsbury, 2013;63–80. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers WA. Virtue ethics and public health: A practice-based -analysis. Monash Bioethics Rev 2004;23:10–21. 10.1007/BF03351406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dresser R. Bioethics and cancer: when the professional becomes personal. Hastings Center Report 2011;41:14–18. 10.1353/hcr.2011.0061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleinman A. The illness narratives: suffering, healing & the human condition. New York: Basic Books, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Hooft S. Suffering and the goals of medicine. Med Health Care Philosophy 1998;1:125–31. 10.1023/A:1009923104175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benatar SR, Doyal L. Human rights abuses: toward balancing two perspectives. Int J Health Serv 2009;39:130–59. 10.2190/HS.39.1.g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker RW. Capitalism's Achilles heel. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Transparency International. Global corruption report 2006. Berlin: Transparency International, 2006. http://archive.transparency.org/publications/gcr/gcr_2006 [Accessed 31 July 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox RC. Doctors Without Borders: Humanitarian Quests, Impossible Dreams of Médecins Sans Frontières. Baltimore, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]