OPC requires IL-17R signaling in mice and humans; IL-17A, but not IL-17F blockade, predisposes to OPC, and functional redundancy among cytokines is evident.

Keywords: fungal, Th17, IL-17R, psoriasis, anticytokine therapy

Abstract

Antibodies targeting IL-17A or its receptor, IL-17RA, are approved to treat psoriasis and are being evaluated for other autoimmune conditions. Conversely, IL-17 signaling is critical for immunity to opportunistic mucosal infections caused by the commensal fungus Candida albicans, as mice and humans lacking the IL-17R experience chronic mucosal candidiasis. IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-17AF bind the IL-17RA-IL-17RC heterodimeric complex and deliver qualitatively similar signals through the adaptor Act1. Here, we used a mouse model of acute oropharyngeal candidiasis to assess the impact of blocking IL-17 family cytokines compared with specific IL-17 cytokine gene knockout mice. Anti-IL-17A antibodies, which neutralize IL-17A and IL-17AF, caused elevated oral fungal loads, whereas anti-IL-17AF and anti-IL-17F antibodies did not. Notably, there was a cooperative effect of blocking IL-17A, IL-17AF, and IL-17F together. Termination of anti-IL-17A treatment was associated with rapid C. albicans clearance. IL-17F-deficient mice were fully resistant to oropharyngeal candidiasis, consistent with antibody blockade. However, IL-17A-deficient mice had lower fungal burdens than anti-IL-17A-treated mice. Act1-deficient mice were much more susceptible to oropharyngeal candidiasis than anti-IL-17A antibody-treated mice, yet anti-IL-17A and anti-IL-17RA treatment caused equivalent susceptibilities. Based on microarray analyses of the oral mucosa during infection, only a limited number of genes were associated with oropharyngeal candidiasis susceptibility. In sum, we conclude that IL-17A is the main cytokine mediator of immunity in murine oropharyngeal candidiasis, but a cooperative relationship among IL-17A, IL-17AF, and IL-17F exists in vivo. Susceptibility displays the following hierarchy: IL-17RA- or Act1-deficiency > anti-IL-17A + anti-IL-17F antibodies > anti-IL-17A or anti-IL-17RA antibodies > IL-17A deficiency.

Introduction

Biologic agents that target IL-17A or IL-17RA are approved for treatment of autoimmune disorders, with particularly encouraging results emerging for psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis [1–5]. However, a potential consequence of such therapies is an increased susceptibility to infections that require an intact IL-17 pathway for host defense. Various studies indicated an essential role for IL-17 and Th17 cells in fungal immunity, particularly to the commensal microbe C. albicans [6]. OPC (thrush) is an opportunistic infection linked to T cell immunosuppression. At-risk cohorts include HIV+/AIDS patients, infants and the elderly; patients receiving chemotherapy or head-neck irradiation; and individuals who use inhaled corticosteroids [7]. In certain PIDs, patients exhibit persistent oral, vaginal, and dermal C. albicans infections, known collectively as CMC [8].

Strikingly, PIDs that lead to mucosal candidiasis are often caused by mutations that impair the IL-17 pathway [9]. Mutations in IL17RA, IL17RC, IL17F, the adaptor ACT1, and the transcription factor RORC have been identified in human CMC [10–13]. APS-1 patients have neutralizing anti-Th17 antibodies that are thought to cause susceptibility to Candida [14, 15]. Moreover, Hyper-IgE/Job’s syndrome is associated with mutations in STAT3 or TPK2 and concomitantly reduced Th17 frequencies [16–20]. In keeping with human data, Il23−/−, IL12b−/−, Il17ra−/−, Il17rc−/−, and Act1−/− mice are susceptible to OPC and dermal candidiasis [21–25]. Thus, the IL-23/IL-17 signaling axis is critically involved in the control of mucocutaneous Candida infections in mice and humans. IL-17 is also implicated in systemic candidiasis in mice, although the release of IFN-γ from Th1 cells also contributes to the activation of neutrophils and macrophages in this setting [26, 27]. Finally, although there is often good agreement regarding the role of the IL-17 pathway in candidiasis between humans and mice, there are species-specific differences that must be kept in mind.

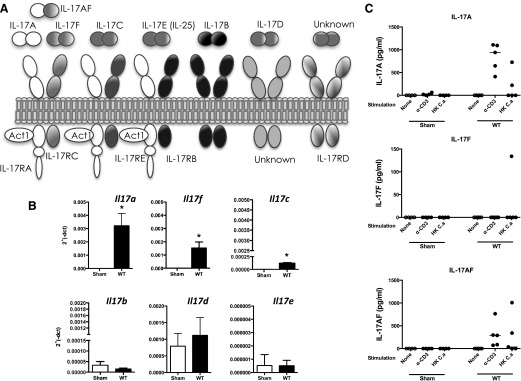

The IL-17 cytokine family has unique structural and functional features [28, 29] (Fig. 1A). IL-17A and IL-17F are the best characterized and signal through a heterodimeric receptor composed of IL-17RA and IL-17RC. This receptor is also used by a heterodimer of IL-17A bound to IL-17F through a covalent disulfide linkage (IL-17AF) [30–34]. These IL-17 variants exhibit qualitatively similar signaling properties but have quantitatively distinct activities, with IL-17A > IL-17AF > IL-17F in terms of signaling potency [35]. The IL-17RA subunit participates in several receptor complexes, pairing with IL-17RB to form the IL-25/IL-17E receptor and with IL-17RE to form the IL-17C receptor [29] (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, IL-17RA is regarded as the common subunit of the IL-17R family, akin to the gp130 subunit of the extended IL-6 family [36].

Figure 1. Expression of IL-17 family cytokines during OPC.

(A) Schematic of IL-17 family cytokine ligands and cognate receptors. (B) WT mice were orally infected with C. albicans, and mRNA from tongues on d 2 was analyzed for expression of the indicated genes by qPCR. *P < 0.05 by Student’s t test. (C) cLN cells from Sham-infected or C. albicans-infected mice were isolated on d 3 or 4 and stimulated for 5 d with anti-CD3 antibodies or heat-killed C. albicans (HK C.a). IL-17 in supernatants were assessed by ELISA. Each point represents 1 mouse.

Downstream responses induced by IL-17A include production of cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-6, G-CSF, and CXCL5, and AMPs, such as β-defensins, calprotectin (S100A8/9), and Lcn2 (24p3) [37]. IL-17-dependent signals are mediated by Act1 (also known as CIKS), which is used by all receptors that incorporate IL-17RA [28]. Consequently, there is considerable overlap in genes induced by IL-17 cytokines, with especially high conservation among IL-17F, IL-17AF, and IL-17C [38]. In contrast, IL-25 (IL-17E) induces genes associated with type 2 immune responses [39–41]. Relatively little is known about IL-17B and IL-17D, although they induce production of IL-6 and TNF-α [38, 42, 43], indicating that they may function similarly to IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-17AF, and IL-17C.

A role for the IL-17 pathway in host defense against mucosal candidiasis is well accepted, but the specific roles of individual IL-17 family cytokines are less well defined. In this study, we sought to understand the implications of anti-IL-17 biologic therapy with respect to the most common form of mucosal candidiasis, OPC. We also compared the effect of anticytokine-blocking antibodies on OPC with the phenotype of IL-17A−/− and IL-17F−/− mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and antibodies

WT mice (C57BL/6J) were from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Habor, ME, USA). IL-17A−/−, IL-17F−/−, and Act1−/− mice were described [44, 45]. All experiments included age- and sex-matched controls. Antibodies IgG2a (clone 54447), IgG1 (clone 43414), α-IL-17A (clone 50104), and α-IL-17RA (clone 657603) were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Anti-IL-17F (clone RN17) and anti-IL-17AF (clone 1402/7C12) were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Mice were injected intraperitoneally at 100–500 μg/injection on d −1, +1, and +2 relative to infection. Unless noted, experiments were performed at least twice.

Oral candidiasis

OPC was performed by sublingual inoculation with 0.225 mg cotton ball saturated in C. albicans (strain CAF2-1) for 75 min under anesthesia, as described [23, 46]. Oral swabs were plated on YPD agar before every experiment to verify the absence of commensal fungi. Tongues were harvested in PBS for fungal-load enumeration or flash frozen for gene-expression analysis. Fungal loads were determined by dissociation on a gentleMACS (Miltenyi Biotec, Cambridge, MA, USA), followed by plating serial dilutions on YPD agar with antibiotics. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal protocols used in this study (animal welfare assurance number A3187-01). All efforts were made to minimize suffering, in accordance with recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from NIH.

RNA analysis

Frozen tongues were lysed using a gentleMACS (Miltenyi Biotec) and total RNA extracted with RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript III First-Strand (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA). Gene expression was determined by qPCR with PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix ROX (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) on a 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primers were from SuperArray Bioscience (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD, USA) and QuantiTect (Qiagen). Concentrations were normalized to Gapdh.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted by a Trizol/RNeasy extraction method with a DNase treatment step to remove DNA contamination. RNA quality was determined on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Target preparation was performed with 1–4 ng RNA using NuGEN Ovation Pico WTA system (NuGEN Technologies, San Carlos, CA, USA). Single primer isothermal amplification (SPIA) cDNAs were fragmented and labeled by use of the Encore Biotin Module (both NuGEN Technologies). Biotinylated cDNA (4.55 μg) was hybridized on Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Microarray slides were stained on Fluidics Workstation 450 and scanned on Scanner 3000 (both Affymetrix) . Results were normalized by use of a MAS 5.0 algorithm (Affymetrix) using a target intensity of 150. Analysis was performed with R and Bioconductor (https://www.bioconductor.org/). Differentially expressed genes were selected by Linear Models for Microarray and RNA-seq Data (LIMMA; https://www.r-project.org/), having a fold change ≥2.0 and a P value ≤0.05. Data are publicly available in ArrayExpress (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MTAB-4167.

In vitro cell culture and ELISA

ST2 cells were cultured in α-MEM with 10% FBS, l-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were treated in duplicate with antibodies for 1 h before 16–18 h treatment with cytokines. IL-17A, IL-17F, or IL-17AF (R&D Systems) was used at 100 ng/ml, and TNF-α (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) was used at 1 ng/ml. cLN cells in AIM V media (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were treated ±2 μg/ml αCD3 (clone 145-2C11; BD Biosciences, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) or heat-killed C. albicans (2 × 106/ml) for 5 d, as described [47]. Cytokine concentrations were determined by ELISA in duplicate (eBioscience).

Statistics

Data were analyzed on Excel and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) using ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test or Student’s t test with Mann-Whitney correction. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-17AF are induced during OPC

To determine the relative roles of IL-17 cytokines in OPC, we evaluated their expression in the oral mucosa of WT mice, 2 d after oral infection with C. albicans [48]. This time point was selected as this is when the major IL-17-driven immune response to acute OPC reaches its peak [23]. As expected, Il17a and Il17f mRNAs were expressed rapidly and robustly [22, 47] (Fig. 1B). Expression of Il17a and Il17f was considerably higher than Il17c (∼12.5-fold), consistent with our recent data that IL-17C−/− and IL-17RE−/− mice are resistant to OPC [49]. Other members of the IL-17 family (Il17e, Il17b, and Il17d) were expressed at low levels (2ΔCT < 0.0006) and were not enhanced following oral Candida exposure (Fig. 1B).

As IL-17AF is a heterodimer, it cannot be distinguished from IL-17A and IL-17F by mRNA expression. Therefore, draining cLN were collected 3–4 d postinfection, stimulated with anti-CD3 antibodies or a heat-killed preparation of C. albicans for 5 d, and concentrations of IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-17AF in culture supernatants were determined. There was negligible production of IL-17A, IL-17AF, or IL-17F in cLN from Sham-treated mice, consistent with the fact that WT mice are naïve to C. albicans [47]. IL-17A and IL-17AF were produced by lymphocytes from C. albicans-infected mice following anti-CD3 activation. They were also expressed after treatment with heat-killed C. albicans, although to a lesser degree (Fig. 1C). Although quantities varied, there was ∼2-fold more IL-17A than IL-17AF produced by anti-CD3-activated cLN cells. In contrast, there was almost no IL-17F in these conditions, suggesting that all of the IL-17F in this setting is in the heterodimeric form. We were not able to measure these cytokines reliably in tongue homogenates (data not shown), although we have verified in situ expression of IL-17A in tongue using a reporter mouse system [22, 50]. These data indicate that IL-17A and IL-17AF are the major IL-17 family cytokines expressed in acute OPC.

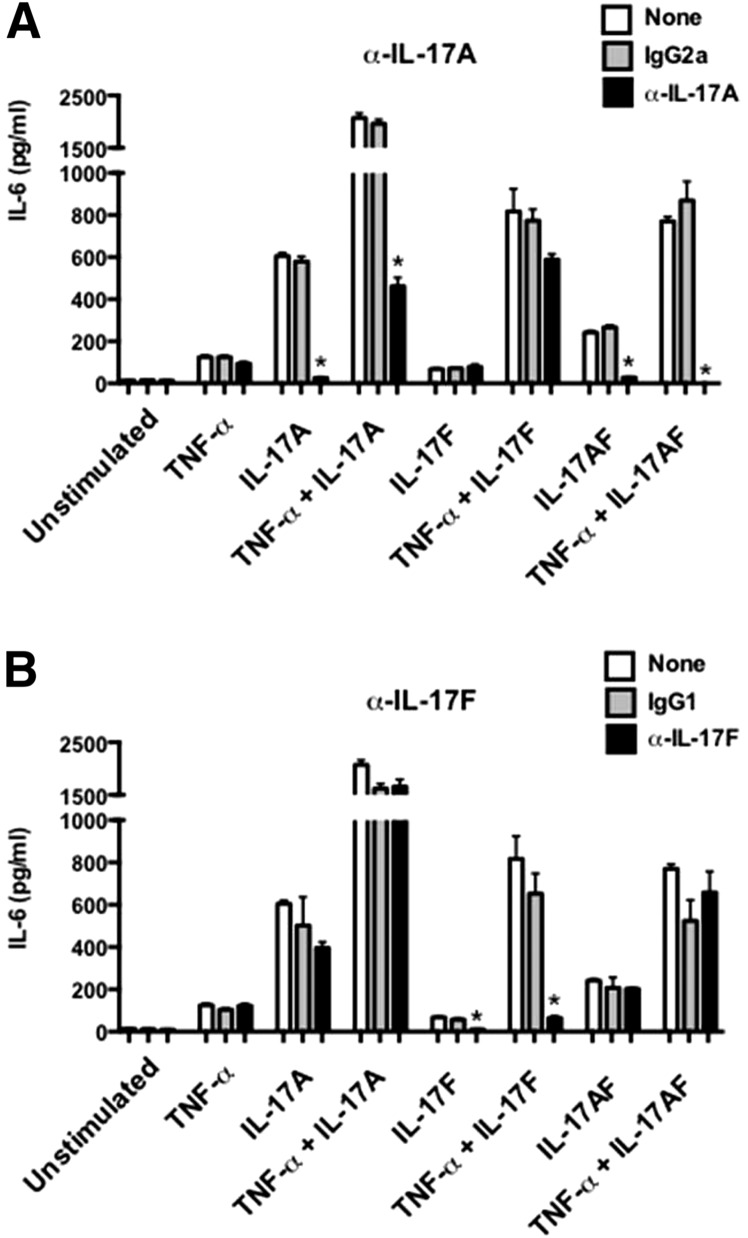

Blocking IL-17A, not IL-17F or IL-17AF, renders mice susceptible to OPC

We next evaluated the impact of blocking IL-17 cytokines in OPC. First, we verified the specificity of available antibodies by assessing their ability to block IL-17-dependent signaling in ST2 cells, a murine stromal cell line [24, 51]. Cells were treated with IL-17A and IL-17F alone or in combination with a suboptimal dose of TNF-α, which signals synergistically with IL-17. IL-6 in conditioned supernatants was measured as a readout for IL-17 activity [52, 53]. Anti-IL-17A antibodies efficiently blocked IL-6 production in ST2 cells treated with IL-17A ± TNF-α but not IL-17F ± TNF-α (Fig. 2A). Anti-IL-17A antibodies also blocked IL-17 activity in cells stimulated with IL-17AF ± TNF-α, verifying that this antibody blocks IL-17A and IL-17AF. Conversely, anti-IL-17F antibodies efficiently blocked signaling by IL-17F ± TNF-α but not IL-17A or IL-17AF ± TNF-α (Fig. 2B). These data confirmed that anti-IL-17A antibodies neutralized IL-17A and IL-17AF, as reported [32], whereas anti-IL-17F antibodies only neutralized IL-17F.

Figure 2. Characterization of neutralizing antibodies.

ST2 bone marrow stromal cells were treated with (A) rat IgG2a or anti-IL-17A antibodies or (B) rat IgG1 or anti-IL-17F antibodies for 1 h and stimulated with IL-17 cytokines overnight (16–18 h). IL-6 production in supernatants was measured by ELISA. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test compared with isotype-treated controls. Data are representative of at least 2 individual experiments.

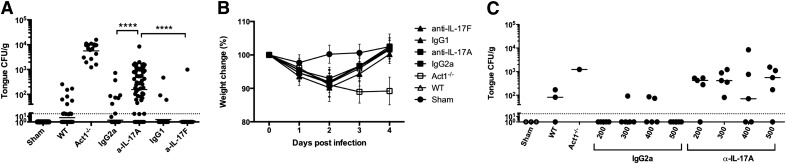

Mice were subjected to OPC with or without anticytokine antibodies. WT mice were administered antibodies on d −1, +1, and +2 relative to infection. They were then infected orally with C. albicans, and weight loss was measured daily. On d 4, oral fungal burden was assessed by plating tongue homogenates. In this model, WT mice clear C. albicans, 3–4 d postinfection, whereas mice lacking IL-17RA or Act1 exhibit constitutively high fungal loads, typically 0.5–1 × 104 CFU/g [23, 54]. The LOD is ∼30 CFU/g tongue tissue (Fig. 3A,; dotted line). As Act1−/− and IL-17RA−/− mice are indistinguishable in their susceptibility to OPC [22, 54], we used Act1−/− mice as controls. Consistent with the fact that C. albicans is not a commensal microbe in mice, Sham-infected mice exhibited no baseline C. albicans colonization [55]. As expected, most WT mice (22/29; 76%) cleared C. albicans by d 4, with a mean fungal burden of 6 CFU/g. WT mice treated with isotype control antibodies cleared C. albicans similarly to WT (48/55; 87%; mean fungal burden = 2 CFU/g). Conversely, most mice treated with anti-IL-17A antibodies had fungal loads well above the LOD (49/59; 83%; mean fungal load = 156 CFU/g; Fig. 3A). However, the fungal load in anti-IL-17A-treated mice was reproducibly 1–1.5 log lower than in the Act1−/− mice. Consistently, Act1−/− mice progressively lost weight during infection, whereas anti-IL-17A-treated mice regained weight by d 4 (Fig. 3B). Even the lowest dose of anti-IL-17A tested (200 µg/mouse) rendered mice susceptible to OPC (mean fungal load = 194 CFU/g; Fig. 3C).

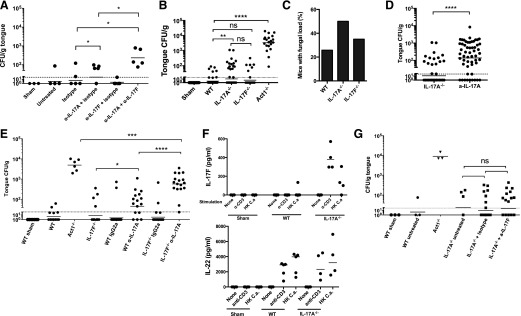

Figure 3. Anti-IL-17A antibodies but not anti-IL-17F antibodies render mice susceptible to OPC.

WT mice were treated with isotype control antibodies or anti-IL-17A or anti-IL-17F antibodies (range 100–500 μg/injection) on d −1, 1, and 2. Mice were subjected to OPC, and (A) oral fungal load was assessed on d 4. Data are pooled from 10 individual experiments. Each point represents an individual mouse, and geometric mean is indicated. ****P < 0.0001 by Mann-Whitney analysis. (B) Weight loss was calculated daily throughout infection. (C) WT mice were treated with the indicated doses of IgG2a or anti-IL-17A antibodies on d −1, 1, and 2, and tongues were harvested on d 4 for fungal burden enumeration. Throughout, dotted, horizontal lines indicate LOD (30 CFU/g). Each point represents 1 mouse, and geometric mean is indicated. All experiments were performed at least twice.

The anti-IL-17A clone used here neutralized IL-17A and IL-17AF (Fig. 2A). Whereas anti-IL-17A treatment led to a reproducible increase in susceptibility to OPC, there was no difference in fungal load between anti-IL-17F-treated mice and isotype antibody-treated or WT-infected mice (CFU = 2.7 and 1.6, respectively; Fig. 3A). This finding was not surprising, given the failure to detect IL-17F in cLN from mice subjected to OPC (Fig. 1C). Therefore, neutralization of IL-17A and/or IL-17AF but not IL-17F caused C. albicans susceptibility. However, the susceptibility following anti-IL-17A antibody treatment was less severe than in Act1−/− mice.

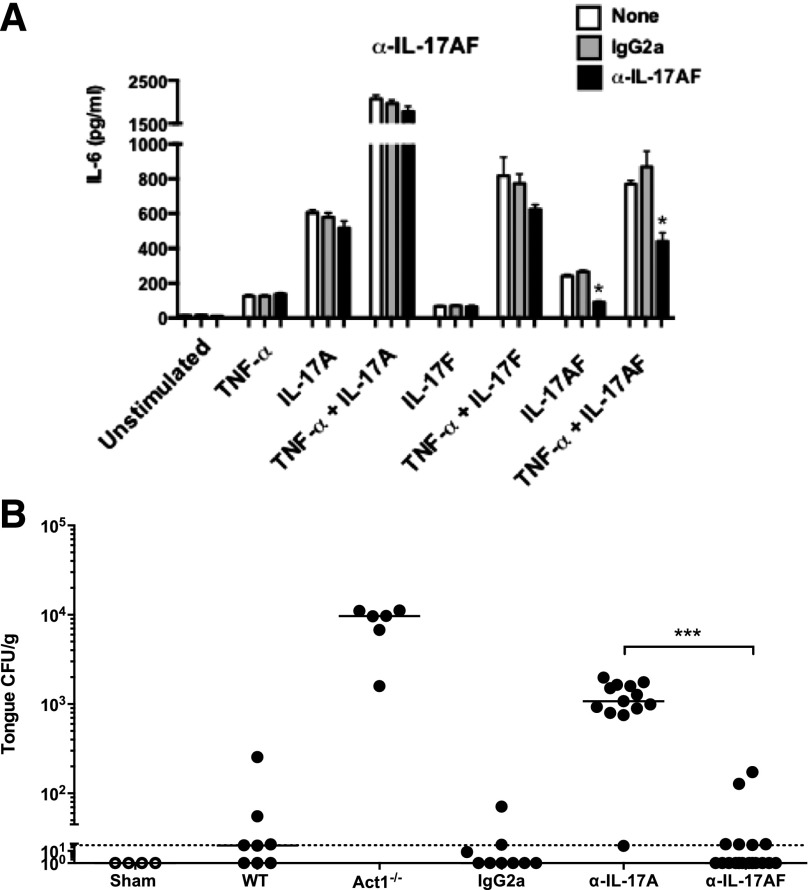

To delineate the role of the IL-17AF heterodimer more selectively, we obtained a panel of untested mAb clones and evaluated the capacity to block IL-17A versus IL-17AF in ST2 cells (Fig. 2). We identified a clone that could neutralize IL-17AF, both alone and in combination with TNF-α. Although neutralization of IL-17AF was incomplete, this antibody showed no blocking activity toward IL-17A or IL-17F (Fig. 4A). Accordingly, WT mice were treated with this anti-IL-17AF clone and subjected to OPC. As shown, mice given anti-IL-17AF antibody had fungal burdens similar to isotype-treated mice (CFU = 21 and 10, respectively), whereas mice treated with anti-IL-17A showed elevated fungal burdens (CFU = 1272; Fig. 4B). These data are consistent with the lower levels of IL-17AF compared with IL-17A that were seen in OPC (Fig. 1C) and indicate that IL-17AF does not appear to contribute significantly to oral anti-Candida defense, at least within the detection limits of this assay system.

Figure 4. Blockade of IL-17AF does not render mice susceptible to OPC.

(A) ST2 cells were treated with IgG2a or α-IL-17AF antibodies for 1 h and stimulated with IL-17A, IL-17F, or IL-17AF overnight, as in Fig. 2. IL-6 in supernatants was measured by ELISA. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test. (B) WT mice were treated with IgG2a, α-IL-17A, or α-IL-17AF antibodies (300 μg/injection) on d −1, +1, and +2. All mice except Sham controls were subjected to OPC, and tongues harvested on d 4 for fungal burden enumeration. Each point represents 1 mouse, and geometric mean is indicated. Dotted, horizontal line indicates LOD (30 CFU/g). ***P < 0.001 by Mann-Whitney analysis.

IL-17A cooperates with IL-17F to mediate immunity to OPC

IL-17A and IL-17F were reported to act synergistically to promote OPC susceptibility [56]. With the use of anti-IL-17A and anti-IL-17F antibodies different from those previously described [56], we found that blocking IL-17A led to an increased susceptibility to OPC at d 4, whereas there was no increase in fungal burden in anti-IL-17F-treated mice compared with isotype-treated or WT-infected mice (Fig. 5A). In contrast, combined blockade of IL-17A and IL-17F led to increased susceptibility to OPC compared with either antibody alone (anti-IL-17A CFU = 32; anti-IL-17A + anti-IL-17F CFU = 234), suggesting cooperative activity of these cytokines (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. OPC susceptibility differs between anti-IL-17 antibody blockade and gene knockout mice.

(A) WT mice were given anti-IL-17A or anti-IL-17F antibodies on d −1, +1, and +2 relative to OPC and tongues harvested for fungal burden enumeration on d 4 postinfection. (B) The indicated mice were subjected to OPC and tongues harvested on d 4 for fungal burden enumeration. (C) Data from B, represented as percentage of mice with detectable fungal load in the tongue. (D) Pooled data from IL-17A−/− and WT mice treated with α-IL-17A antibodies were compared in aggregate. (E) The indicated mice were treated with IgG2a or α-IL-17A antibodies (300 μg) on d −1, 1, and 2. Mice were subjected to OPC and fungal loads assessed on d 4. (F) cLN cells from C. albicans-infected mice were isolated on d 3 and stimulated for 5 d with anti-CD3 antibodies or heat-killed C. albicans extract. IL-17F and IL-22 were assessed in supernatants by ELISA. (G) The indicated mice were treated with isotype or α-IL-17F antibodies (300 μg) on d −1, 1, and 2. Mice were subjected to OPC and fungal loads assessed on d 4. Throughout, dotted, horizontal lines indicate LOD (30 CFU/g). Each point represents 1 mouse, and geometric mean is indicated. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by Mann-Whitney analysis; ns, not significant.

As an independent approach to interrogate the role of IL-17 cytokines in OPC, we evaluated IL-17A−/− and IL-17F−/− mice. In disseminated candidiasis, IL-17A−/− mice show increased disease susceptibility similar to IL-17RA−/− mice, whereas IL-17F−/− mice do not [57]. It was reported that there is no difference in susceptibility to OPC between IL-17A+/− and IL-17A−/− mice [56]. However, in the latter study, only 3 mice per cohort were tested, and mice deficient in IL-17R signaling (e.g., IL-17RA−/− or Act1−/−) were not used as comparators. Accordingly, we subjected 32 IL-17A−/− mice to OPC in multiple independent experiments. IL-17A−/− mice showed statistically elevated fungal burdens compared with WT (Fig. 5B and C), but fungal burdens were reproducibly and statistically lower than observed in anti-IL-17A-treated mice (Fig. 5D). The IL-17F−/− mice were not statistically different from WT mice (Fig. 5B), and a lower percentage of mice presented with a fungal load compared with IL-17A−/− mice (although, on average, elevated compared with WT mice; Fig. 5C). Although these findings support the concept that IL-17A and not IL-17F is important for immunity to OPC, they also demonstrate that IL-17A alone does not fully explain the susceptibility seen in Act1−/− animals.

The dichotomy between IL-17A−/− mice and anti-IL-17A treatment raised the possibility that there may be developmental compensation between IL-17A and IL-17F. To test this hypothesis, we treated IL-17F−/− mice with anti-IL-17A antibodies and subjected them to OPC. As shown, anti-IL-17A-treated WT mice had a lower mean fungal load than IL-17F−/− mice treated with anti-IL-17A antibodies (45 vs. 576 CFU/g; Fig. 5E). Still, IL-17F−/− mice treated with anti-IL-17A antibodies had lower fungal burdens than Act1−/− mice (576 vs. 4954 CFU/g). Thus, there is cooperative antifungal activity between IL-17A and IL-17F, even though blockade of IL-17F on its own does not cause disease susceptibility, and a complete signaling knockout (as in Act1−/− mice) has an even higher fungal burden.

Based on these results, we reasoned that blockade of IL-17F in IL-17A−/− mice might further increase susceptibility to OPC. In support of this idea, cLNs isolated from IL-17A−/− mice produced elevated amounts of IL-17F compared with WT following stimulation with anti-CD3 antibodies or heat-killed C. albicans extract (Fig. 5F). Conversely, we did not see elevated levels of IL-22 compared with WT, another Th17-derived cytokine that is host protective in OPC [23] (Fig. 5F). Therefore, we neutralized IL-17F in the IL-17A−/− mice and evaluated OPC. Surprisingly, IL-17A−/− mice treated with anti-IL-17F antibodies presented with similar fungal burdens to control IL-17A−/− mice (Fig. 5G). These data suggest that alternate compensatory mechanisms may exist in the IL-17A−/− mice to protect against OPC, although the basis for this remains unclear.

Genes associated with susceptibility to OPC following IL-17A blockade

In OPC, IL-17RA signaling rapidly induces a panel of genes that contributes to the antifungal response, including AMPs and neutrophil-attracting cytokines and chemokines [23, 47]. In WT mice, expression of these genes returns to baseline as the infection is cleared (4–5 d). Therefore, at 2 days post-infection, we analyzed representative IL-17R-responsive genes associated with antibody blockade, including Defb3, Lcn2, and CXCL5 (Cxcl5). In WT mice treated with 500 μg antibody—the highest antibody dose used in these studies—there was a significant reduction in Lcn2 and Cxcl5 expression but no change in Defb3 (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, Lcn2 and Cxcl5 were also reduced in isotype antibody-treated mice, although these mice were resistant to OPC (Fig. 6A). We also analyzed gene expression in WT mice treated with 200 μg IgG2a or anti-IL-17A antibodies, plus 300 μg IgG1 antibodies. Again, there was reduced expression of Lcn2, but in this setting, Defb3 expression was also reduced in mice treated with anti-IL-17A antibodies compared with WT and isotype antibody-treated mice (Fig. 6B). Thus, the IgG2a isotype control antibodies appear to influence gene expression at high doses but did not correlate with susceptibility to OPC. Therefore, the increased fungal loads in anti-IL-17A antibody-treated mice were unlikely a result of decreased expression of Lcn2 or Cxcl5, which is consistent with published data [54, 58].

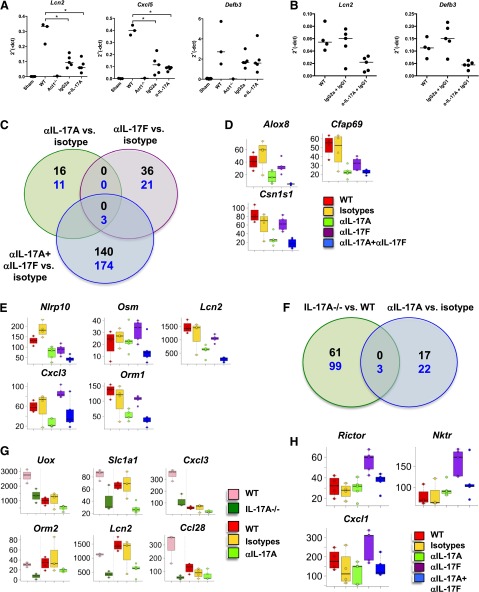

Figure 6. Gene-expression changes associated with OPC susceptibility.

(A and B) WT mice were treated with different doses of IgG2a or IgG1 or anti-IL-17A antibodies, and gene expression was assessed by qPCR. Expression was normalized to Gapdh. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test. All experiments were performed at least twice. (C and F) Venn diagrams of significant genes for anti-IL-17A, anti-IL-17F or anti-IL-17A + anti-IL-17F versus isotype control-treated mice. Thresholds used were fold change ≥ |2|, and P ≤ 0.05. Black numbers indicate up-regulated genes, and blue numbers indicate down-regulated genes. (D, E, G, and H) Box plots for selected genes showing the median, lower, and upper quartiles for the group-expression level. Individual dots show the MAS5-normalized linear intensity for individual animals.

We next performed detailed microarray analysis of tongue mRNA isolated 2 d after C. albicans infection, when fungal loads are similar and Il17a expression is at a maximum [47]. Broadly speaking, C. albicans infection triggered numerous transcriptional changes in tongue, with 1113 up-regulated and 1217 down-regulated genes (P ≤ 0.05 and fold change ≥ |2|). Changes were associated with (but not limited to) the modulation of cytokine and chemokines and their receptors, innate and adaptive immune-responsive genes, epithelial cell-associated genes (including structural genes), cell-cycle-associated genes, and apoptosis- and stress-related genes.

Principal component analysis indicated that anti-IL-17A and isotype antibody treatment were similar to WT mice infected with C. albicans, whereas anti-IL-17F and the combined anti-IL-17A + anti-IL-17F groups clearly separated from the aforementioned treatments and from each other (data not shown). This trend is reflected in the larger number of differentially modulated and overlapping genes in the anti-IL-17F and the combined anti-IL-17A + anti-IL-17F groups compared with the anti-IL-17A group (Fig. 6C). We then asked which genes were associated with susceptibility to C. albicans infection by focusing on genes down-modulated in the anti-IL-17A and the combined anti-IL-17A + anti-IL-17F groups. We excluded modulated genes that were not associated with an OPC phenotype, such as anti-IL-17F treatment alone. The resulting genes were Alox8, Cfap69, Csn1s1, Vnn3, Lpo, Uox, Krt1, and Atp13a4 (Fig. 6D, and data not shown). Other genes of interest were those that were down-regulated in the combined anti-IL-17A + anti-IL-17F group; although these did not pass significance-threshold cutoffs, nonetheless, they showed a similar trend in anti-IL17A-treated animals. These were Nlrp10, Osm, IL-36a (IL1f6), CD62 ligand (Sell), Slc1a1, Cxcl3, Lcn2, Casp14, and Orm1; Fig. 6E, and data not shown).

We reasoned that genes affected in anti-IL-17A and IL-17A−/− mice were the most likely to be important for C. albicans clearance. Therefore, we compared genes that were differentially modulated in IL-17A−/− with anti-IL-17A-treated mice. Again, surprisingly, few genes were differentially expressed (Fig. 6F), which included Cxcl3, Slc1a1, and Uox (Fig. 6G, upper row). Other genes of interest that were down-modulated in the IL-17A−/− group mice and showed a similar trend in the anti-IL-17A group (but did not pass significance thresholds) were Adamts4, Ccl28, Lcn2, and Orm2 (Fig. 6G, lower row, and data not shown). We asked whether transcriptional changes in the anti-IL-17F cohort might account for protection against Candida infection. Cxcl1, Nktr, and Rictor (Fig. 6H) were up-regulated in the anti-IL-17F-treated animals only. In summary, IL-17A neutralization only partially phenocopies IL-17A−/− at the level of gene expression.

Candida clearance upon termination of anti-IL-17A antibody treatment

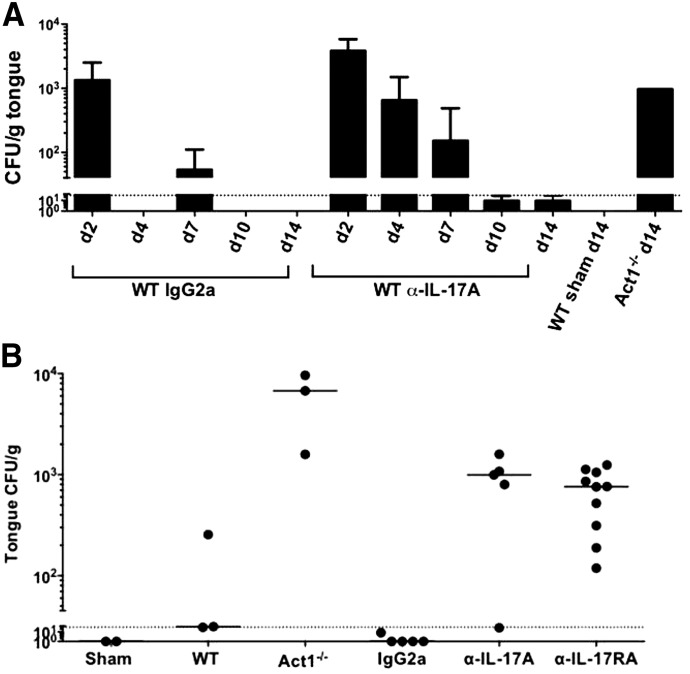

To determine the duration of anti-IL-17A antibodies with respect to oral Candida colonization, mice were treated with anti-IL-17A antibodies on d −1, +1 and +2, and fungal burdens assessed up to 14 d postinfection. Whereas mice treated with anti-IL-17A showed elevated fungal burdens at d 4, the fungal loads in anti-IL-17A antibody-treated mice decreased over time, with complete clearance observed by d 10 (Fig. 7A). Clearance of C. albicans in anti-IL-17A-treated mice at d 14 contrasted with Act1−/− mice, which maintained a fungal burden and weight loss (Fig. 7A, and data not shown). Therefore, although anti-IL-17A antibody treatment transiently renders mice susceptible to OPC, a protective immune response is elicited rapidly following its discontinuation.

Figure 7. Anti-IL-17A and anti-IL-17RA antibodies result in comparable OPC susceptibility.

(A) WT mice were injected with PBS (Sham), IgG2a, or α-IL-17A antibodies (500 μg) on d −1, +1, and +2. Mice were subjected to OPC and fungal loads assessed on the indicated days postinfection. (B) The indicated mice were treated with IgG2a or α-IL-17A or α-IL-17RA antibodies (300 μg) on d −1, +1, and +2. Mice were subjected to OPC and fungal burdens assessed on d 4. Throughout, each point represents 1 mouse, and geometric mean is indicated. Dotted, horizontal lines indicate LOD (30 CFU/g).

Clinical trials testing anti-IL-17RA antibodies have shown similar results to anti-IL-17A studies [3]. Our data indicate that in gene knockout mice, IL-17RA−/− or Act1−/− is more severe than IL-17A−/− (Fig. 5B; [22, 54]). To compare receptor versus ligand differences in susceptibility with OPC following antibody blockade, WT mice were treated with anti-IL-17A or anti-IL-17RA antibodies and subjected to OPC for 4 d (Fig. 7B). Fungal burdens were comparable between anti-IL-17A and anti-IL-17RA antibody-treated mice (CFU/g = 553 or 517, respectively; Fig. 7B). These data indicate that tool antibodies targeting IL-17A or IL-17RA have equivalent effects on susceptibility to OPC. Furthermore, anti-IL-17RA treatment does not result in the same severity of disease as shown in IL-17RA−/− or Act1−/− mice subjected to OPC [54].

DISCUSSION

Drugs targeting IL-17A and IL-17RA have shown efficacy for autoimmune psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis [1, 59]. Anti-IL-17A therapy causes increased rates of infections compared with placebo, particularly mucocutaneous candidiasis [4, 9]. Although infection rates were comparable between anti-IL-17A therapy and etanercept (soluble TNFR), Candida infections were more common in the anti-IL-17A-treated cohorts. Nonetheless, Candida infections, following anti-IL-17A therapy, were nonserious—clearing naturally or following standard antifungal therapy; none resulted in CMC or systemic candidiasis [5]. Our data parallel these observations, as C. albicans was cleared from mice following discontinuation of anti-IL-17A treatment (Fig. 7A). Together, these preclinical and clinical data demonstrate that blocking IL-17A in vivo suppresses protective immunity to C. albicans in a transient, mild-to-moderate, and reversible manner.

Whereas several IL-17 family cytokines were up-regulated in OPC (Fig. 1), our data indicate the following: 1) that IL-17A appears to be the primary IL-17 family cytokine in defense against murine OPC, and 2) that IL-17A cooperates functionally with IL-17F. Specifically, whereas IL-17F−/− and anti-IL-17F-treated mice did not exhibit detectable fungal loads (Fig. 3A) [56], IL-17F−/− mice treated with anti-IL-17A antibodies were more susceptible to OPC than WT mice (Fig. 5E). The relevance of these findings to human disease is consistent with the observation that APS-1 or thymoma patients with neutralizing autoantibodies against IL-17 cytokines experience CMC [14, 15]. Functional synergy between IL-17A and IL-17F has similarly been demonstrated in response to Staphylococcus aureus, another infection associated with IL-17RA−/− or IL-17F−/− [11, 60].

Accordingly, it might be predicted that antibodies targeting the common receptor chain IL-17RA would show an increased risk of infections compared with anti-IL-17A antibodies. Although our data in a 4 d acute OPC model do not support this hypothesis (Fig. 7B), we cannot rule out the possibility that the tool antibodies used here may differ in their binding and kinetic characteristics from therapeutic reagents used in patients. To date, there do not appear to be major differences in susceptibility to infections between patients receiving anti-IL-17RA antibodies and those receiving anti-IL-17A antibodies, although no side-by-side comparison has been reported. Larger or more long-term studies in humans will be needed to determine the true extent and circumstances in which anti-IL-17 biologic therapies cause infectious disease.

One conclusion from this study is that findings in gene knockout mice do not perfectly mirror those made with blocking antibodies, and that absence of IL-17A from birth may allow compensatory mechanisms to develop. One candidate for such compensation is IL-22, as IL-22−/− mice are susceptible to OPC [23], and APS-1 patients with CMC harbor neutralizing antibodies against IL-22, as well as IL-17A and IL-17F [14, 15]. However, IL-17A−/− mice did not produce increased levels of IL-22 compared with WT mice (Fig. 5F). Although IL-17A−/− mice produced elevated levels of IL-17F, anti-IL-17F antibody treatment did not further increase the susceptibility of IL-17A−/− mice to OPC, suggesting that IL-17F does not compensate in this setting (Fig. 5G). Nonetheless, as the anti-IL-17F clone used here did not fully block the activity of IL-17F (Fig. 2), we cannot absolutely rule out a role for IL-17F. Thus, it remains to be determined which factor or factors compensate for the loss of IL-17A in IL-17A−/− mice during OPC. Along these lines, we have no direct evidence for compensation by IL-17A in IL-17F−/− mice. IL-17A levels in IL-17F−/− mice were reported to be normal in Citrobacter rodentium-infected mice [44], and IL-17A levels were actually lower under physiologic conditions in a different strain of IL-17F−/− mice [61]. Still, the blocking of IL-17A in IL-17F−/− mice (Fig. 5E) increased susceptibility over anti-IL-17A blockade in WT mice, indicating the cooperative activity of these cytokines in vivo.

To date, most known human mutations associated with CMC affect IL-17 signaling or generation of IL-17-secreting cells [9]. Many mutations (e.g., IL17RA, IL17RC, and ACT1 [10–12]) affect the signaling of more than 1 cytokine. However, alteration in a single gene (IL17F) was identified in 1 kindred of CMC patients. This mutation exerted a dominant-negative phenotype, wherein signaling by both IL-17F and IL-17AF is inhibited by the mutant IL-17F protein [11]. IL-17A in these patients was normal, yet their symptoms phenocopied the IL-17RA−/− patient. One interpretation of this observation is that IL-17F and/or IL-17AF may be more important for anti-Candida immunity in humans than in mice. However, our data, with the use of a new anti-IL-17AF-blocking antibody, suggest a redundant role for IL-17AF during OPC (Fig. 4B), with the caveat that IL-17AF signaling was only blocked ∼50% in vitro with this reagent. Moreover, although the anti-IL-17AF antibody was specific in vitro, we do not know its efficacy in vivo. Nonetheless, this study is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate the role of the IL-17AF heterodimer in the context of fungal immunity.

To understand mechanisms underlying sensitivity to OPC, we performed microarray analyses on tongue of knockout and antibody-treated mice, focusing on pathway-related genes. Remarkably few genes were differentially regulated in mice treated with anti-IL-17A and anti-IL-17F or IL-17A−/− compared with WT and IL-17F−/− mice (Fig. 6). We speculate that the impairment in a combination of factors in anti-IL-17A-treated or IL-17A−/− mice, rather than a deficiency in an individual gene or gene product, causes susceptibility to OPC. Several genes of interest, not previously linked to OPC, were identified here based on their selective sensitivity to IL-17A blockade. Some of the most plausible candidate genes included Orm1 and Orm2, Nlrp10, and Osm. Orm1 and Orm2 are Lcn family members that bind CCR5 and drive opportunistic infections through polarization of monocytes to immunosuppressive M2 macrophages [62, 63]. Nlrp10 was shown to induce Candida-specific Th1 and Th17 responses [64], and Osm plays a role in keratinocyte differentiation in synergy with IL-17A and IL-22 [65]. Also noteworthy was the reduced expression of Ccl28 in anti-IL-17A-treated and IL-17A−/− mice (Fig. 6G). CCL28 has antimicrobial activity against C. albicans [66], and its C terminus has intriguing similarity to histatin-5, a salivary candidacidal AMP [67]. There is no known histatin-5 homolog in mice, so it is conceivable that CCL28 is its mouse counterpart.

Cxcl1 and Cxcl3 encode IL-17A-induced, neutrophil-attracting chemokines [68]; their decreased expression correlates with the clinically observed decreased CXCL1 expression and almost complete clearance of neutrophils in psoriasis patients treated with anti-IL-17A [69]. By contrast, Cxcl1 and Cxcl3 were up-regulated in anti-IL-17F antibody-treated mice, with no OPC phenotype. Differences in gene expression and OPC susceptibility between anti-IL-17A and anti-IL-17F antibody-treated mice highlight the importance of neutrophils in the early phase of host defense to C. albicans. Moreover, IL-17A controls IL-17F production and maintains blood neutrophil counts in mice [70], perhaps explaining the differential susceptibility to OPC observed here. Overall, the significance of these gene changes and their products in mucocutaneous host resistance to C. albicans clearly requires further study.

There are important differences between humans and mice in terms of mucosal candidiasis, and therefore, the data presented here should not be assumed to translate perfectly to patients. Humans harbor C. albicans as a commensal microbe, whereas mice are naïve to this organism. Adult humans harbor a potent adaptive CD4+Th17 response toward this fungus [71, 72], and generation of an adaptive Th17 response has been similarly shown in mouse Candida rechallenge models [47, 73]. The acute 4 d OPC model used here represents an innate response, in which IL-17 derives from γδ-T cells and "natural" Th17 cells [22]; if also true in humans, it would likely reflect responses in infants. As adults are the main patient group treated with anti-IL-17 therapeutics, studies dissecting the requirements of individual IL-17 cytokines in OPC in innate versus adaptive experimental settings will prove valuable.

In conclusion, results from an acute mouse OPC model are in line with data that anti-IL-17 therapy in patients leads to a reproducible but mild increase in the frequency of mucosal C. albicans infections. The observation that <5% of patients receiving anti-IL-17A antibody treatment developed mild-to-moderate mucosal candidiasis [69] suggests that susceptibility is likely a result of a combination of factors rather than a deficiency in just 1 cytokine. IL-17RA−/− or Act1−/− were more severely affected than IL-17A−/− mice, yet IL-17RA blockade by antibodies was similar to anti-IL-17A treatment (Fig. 7B). Whereas the clearance of acute OPC was delayed in mice following IL-17A neutralization, dissemination did not occur (data not shown). This finding is important clinically, given the high fatality rate of disseminated C. albicans infections (40–80%) [74]. Disseminated Candida infections have not been observed in psoriatic patients receiving anti-IL-17A antibody treatment. Thus, mucocutaneous Candida infections arising from anti-IL-17 antibody therapy, unlike in primary immunodeficiency conditions, can be mild to moderate, transient, and controllable by standard therapy.

AUTHORSHIP

N.W., E. Tritto, E. Traggiai, F.K., M.K., and S.L.G. designed experiments. N.W., E. Tritto, E. Traggiai, P.M., D.B., B.M.C., A.J.M., A.V.G., J.R.J., U.S., M.K., and S.L.G. performed experiments or analyzed data. N.W., M.K., E. Tritto, and S.L.G. wrote the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S.L.G. was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH; Grants DE022550, DE023815, and AI107825) and a grant from Novartis. U.S. was supported by the Intramural Research Program of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. The authors thank Dr. Y. Iwakura, University of Tokyo, for kindly providing IL-17A−/− and IL-17F−/− mice and Drs. M. McGeachy, J. Kolls, A. Waisman, and P. Biswas for helpful suggestions.

Glossary

- ΔCT

difference in comparative threshold

- −/−

deficient/knockout

- Act1

activator 1

- Adamts4

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 4

- Alox8

arachidonate 8-lipoxygenase

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- APS-1

autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome 1

- Atp13a4

ATPase type 13A4

- Cfap69

cilia- and flagella-associated protein 69

- cLN

cervical lymph node

- CMC

chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis

- Csn1s1

casein alpha s1

- Defb3

β-defensin 3

- Krt1

keratin 1

- Lcn2

lipocalin-2

- LOD

limit of detection

- Lpo

lactoperoxidase

- Nktr

NK cell-triggering receptor

- NLRP10

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 10

- OPC

oropharyngeal candidiasis

- Orm1/2

orosomucoid 1/2

- Osm

oncostatin M

- PID

primary immunodeficiency disease

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- Rictor

regulatory-associated protein of mechanistic target of rapamycin, complex 1-independent companion of mechanistic target of rapamycin, complex 2

- Slc1a1

solute carrier family 1

- Uox

urate oxidase

- Vnn3

vanin3

- WT

wild-type

- YPD

yeast peptone dextrose

DISCLOSURES

S.L.G. has consulted for Novartis, Janssen, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer and has received a research grant, honoraria, and travel reimbursements from Novartis. E. Tritto, E. Traggiai, F.K., P.M., D.B., and M.K. are full-time employees of Novartis. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. There are no other conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel D. D., Lee D. M., Kolbinger F., Antoni C. (2013) Effect of IL-17A blockade with secukinumab in autoimmune diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72(Suppl 2), ii116–ii123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonardi C., Matheson R., Zachariae C., Cameron G., Li L., Edson-Heredia E., Braun D., Banerjee S. (2012) Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 1190–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papp K. A., Leonardi C., Menter A., Ortonne J. P., Krueger J. G., Kricorian G., Aras G., Li J., Russell C. B., Thompson E. H., Baumgartner S. (2012) Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ERASURE Study Group; FIXTURE Study Group (2014) Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 326–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanford M., McKeage K. (2015) Secukinumab: first global approval. Drugs 75, 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huppler A. R., Bishu S., Gaffen S. L. (2012) Mucocutaneous candidiasis: the IL-17 pathway and implications for targeted immunotherapy. Arthritis Res. Ther. 14, 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fidel P. L., Jr (2011) Candida-host interactions in HIV disease: implications for oropharyngeal candidiasis. Adv. Dent. Res. 23, 45–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glocker E., Grimbacher B. (2010) Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and congenital susceptibility to Candida. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 10, 542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milner J. D., Holland S. M. (2013) The cup runneth over: lessons from the ever-expanding pool of primary immunodeficiency diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 635–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boisson B., Wang C., Pedergnana V., Wu L., Cypowyj S., Rybojad M., Belkadi A., Picard C., Abel L., Fieschi C., Puel A., Li X., Casanova J.-L. (2013) An ACT1 mutation selectively abolishes interleukin-17 responses in humans with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Immunity 39, 676–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puel A., Cypowyj S., Bustamante J., Wright J. F., Liu L., Lim H. K., Migaud M., Israel L., Chrabieh M., Audry M., Gumbleton M., Toulon A., Bodemer C., El-Baghdadi J., Whitters M., Paradis T., Brooks J., Collins M., Wolfman N. M., Al-Muhsen S., Galicchio M., Abel L., Picard C., Casanova J.-L. (2011) Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science 332, 65–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling Y., Cypowyj S., Aytekin C., Galicchio M., Camcioglu Y., Nepesov S., Ikinciogullari A., Dogu F., Belkadi A., Levy R., Migaud M., Boisson B., Bolze A., Itan Y., Goudin N., Cottineau J., Picard C., Abel L., Bustamante J., Casanova J. L., Puel A. (2015) Inherited IL-17RC deficiency in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J. Exp. Med. 212, 619–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okada S., Markle J. G., Deenick E. K., Mele F., Averbuch D., Lagos M., Alzahrani M., Al-Muhsen S., Halwani R., Ma C. S., Wong N., Soudais C., Henderson L. A., Marzouqa H., Shamma J., Gonzalez M., Martinez-Barricarte R., Okada C., Avery D. T., Latorre D., Deswarte C., Jabot-Hanin F., Torrado E., Fountain J., Belkadi A., Itan Y., Boisson B., Migaud M., Arlehamn C. S., Sette A., Breton S., McCluskey J., Rossjohn J., de Villartay J. P., Moshous D., Hambleton S., Latour S., Arkwright P. D., Picard C., Lantz O., Engelhard D., Kobayashi M., Abel L., Cooper A. M., Notarangelo L. D., Boisson-Dupuis S., Puel A., Sallusto F., Bustamante J., Tangye S. G., Casanova J. L. (2015) Immunodeficienes. Impairment of immunity to Candida and Mycobacterium in humans with bi-allelic RORC mutations. Science 349, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puel A., Döffinger R., Natividad A., Chrabieh M., Barcenas-Morales G., Picard C., Cobat A., Ouachée-Chardin M., Toulon A., Bustamante J., Al-Muhsen S., Al-Owain M., Arkwright P. D., Costigan C., McConnell V., Cant A. J., Abinun M., Polak M., Bougnères P. F., Kumararatne D., Marodi L., Nahum A., Roifman C., Blanche S., Fischer A., Bodemer C., Abel L., Lilic D., Casanova J. L. (2010) Autoantibodies against IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J. Exp. Med. 207, 291–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kisand K., Bøe Wolff A. S., Podkrajsek K. T., Tserel L., Link M., Kisand K. V., Ersvaer E., Perheentupa J., Erichsen M. M., Bratanic N., Meloni A., Cetani F., Perniola R., Ergun-Longmire B., Maclaren N., Krohn K. J., Pura M., Schalke B., Ströbel P., Leite M. I., Battelino T., Husebye E. S., Peterson P., Willcox N., Meager A. (2010) Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in APECED or thymoma patients correlates with autoimmunity to Th17-associated cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 207, 299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milner J. D., Brenchley J. M., Laurence A., Freeman A. F., Hill B. J., Elias K. M., Kanno Y., Spalding C., Elloumi H. Z., Paulson M. L., Davis J., Hsu A., Asher A. I., O’Shea J., Holland S. M., Paul W. E., Douek D. C. (2008) Impaired T(H)17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature 452, 773–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minegishi Y., Karasuyama H. (2008) Genetic origins of hyper-IgE syndrome. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 8, 386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renner E. D., Rylaarsdam S., Anover-Sombke S., Rack A. L., Reichenbach J., Carey J. C., Zhu Q., Jansson A. F., Barboza J., Schimke L. F., Leppert M. F., Getz M. M., Seger R. A., Hill H. R., Belohradsky B. H., Torgerson T. R., Ochs H. D. (2008) Novel signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) mutations, reduced T(H)17 cell numbers, and variably defective STAT3 phosphorylation in hyper-IgE syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 122, 181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wjst M., Lichtner P., Meitinger T., Grimbacher B. (2009) STAT3 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and STAT3 mutations associated with hyper-IgE syndrome are not responsible for increased serum IgE serum levels in asthma families. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 17, 352–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minegishi Y., Karasuyama H. (2009) Defects in Jak-STAT-mediated cytokine signals cause hyper-IgE syndrome: lessons from a primary immunodeficiency. Int. Immunol. 21, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farah C. S., Hu Y., Riminton S., Ashman R. B. (2006) Distinct roles for interleukin-12p40 and tumour necrosis factor in resistance to oral candidiasis defined by gene-targeting. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 21, 252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conti H. R., Peterson A. C., Brane L., Huppler A. R., Hernández-Santos N., Whibley N., Garg A. V., Simpson-Abelson M. R., Gibson G. A., Mamo A. J., Osborne L. C., Bishu S., Ghilardi N., Siebenlist U., Watkins S. C., Artis D., McGeachy M. J., Gaffen S. L. (2014) Oral-resident natural Th17 cells and γδ T cells control opportunistic Candida albicans infections. J. Exp. Med. 211, 2075–2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conti H. R., Shen F., Nayyar N., Stocum E., Sun J. N., Lindemann M. J., Ho A. W., Hai J. H., Yu J. J., Jung J. W., Filler S. G., Masso-Welch P., Edgerton M., Gaffen S. L. (2009) Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J. Exp. Med. 206, 299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho A. W., Shen F., Conti H. R., Patel N., Childs E. E., Peterson A. C., Hernández-Santos N., Kolls J. K., Kane L. P., Ouyang W., Gaffen S. L. (2010) IL-17RC is required for immune signaling via an extended SEF/IL-17R signaling domain in the cytoplasmic tail. J. Immunol. 185, 1063–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagami S., Rizzo H. L., Kurtz S. E., Miller L. S., Blauvelt A. (2010) IL-23 and IL-17A, but not IL-12 and IL-22, are required for optimal skin host defense against Candida albicans. J. Immunol. 185, 5453–5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netea M. G., Maródi L. (2010) Innate immune mechanisms for recognition and uptake of Candida species. Trends Immunol. 31, 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang W., Na L., Fidel P. L., Schwarzenberger P. (2004) Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaffen S. L., Jain R., Garg A., Cua D. (2014) The IL-23-IL-17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 585–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwakura Y., Ishigame H., Saijo S., Nakae S. (2011) Functional specialization of interleukin-17 family members. Immunity 34, 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang S. H., Dong C. (2007) A novel heterodimeric cytokine consisting of IL-17 and IL-17F regulates inflammatory responses. Cell Res. 17, 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ely L. K., Fischer S., Garcia K. C. (2009) Structural basis of receptor sharing by interleukin 17 cytokines. Nat. Immunol. 10, 1245–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang S. C., Long A. J., Bennett F., Whitters M. J., Karim R., Collins M., Goldman S. J., Dunussi-Joannopoulos K., Williams C. M., Wright J. F., Fouser L. A. (2007) An IL-17F/A heterodimer protein is produced by mouse Th17 cells and induces airway neutrophil recruitment. J. Immunol. 179, 7791–7799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright J. F., Bennett F., Li B., Brooks J., Luxenberg D. P., Whitters M. J., Tomkinson K. N., Fitz L. J., Wolfman N. M., Collins M., Dunussi-Joannopoulos K., Chatterjee-Kishore M., Carreno B. M. (2008) The human IL-17F/IL-17A heterodimeric cytokine signals through the IL-17RA/IL-17RC receptor complex. J. Immunol. 181, 2799–2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright J. F., Guo Y., Quazi A., Luxenberg D. P., Bennett F., Ross J. F., Qiu Y., Whitters M. J., Tomkinson K. N., Dunussi-Joannopoulos K., Carreno B. M., Collins M., Wolfman N. M. (2007) Identification of an interleukin 17F/17A heterodimer in activated human CD4+ T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13447–13455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fouser L. A., Wright J. F., Dunussi-Joannopoulos K., Collins M. (2008) Th17 cytokines and their emerging roles in inflammation and autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 226, 87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozaki K., Leonard W. J. (2002) Cytokine and cytokine receptor pleiotropy and redundancy. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29355–29358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onishi R., Gaffen S. L. (2010) Interleukin-17 and its target genes: mechanisms of interleukin-17 function in disease. Immunology 129, 311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H., Chen J., Huang A., Stinson J., Heldens S., Foster J., Dowd P., Gurney A. L., Wood W. I. (2000) Cloning and characterization of IL-17B and IL-17C, two new members of the IL-17 cytokine family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 773–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fort M. M., Cheung J., Yen D., Li J., Zurawski S. M., Lo S., Menon S., Clifford T., Hunte B., Lesley R., Muchamuel T., Hurst S. D., Zurawski G., Leach M. W., Gorman D. M., Rennick D. M. (2001) IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity 15, 985–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angkasekwinai P., Park H., Wang Y. H., Wang Y. H., Chang S. H., Corry D. B., Liu Y. J., Zhu Z., Dong C. (2007) Interleukin 25 promotes the initiation of proallergic type 2 responses. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J., Ho W. H., Maruoka M., Corpuz R. T., Baldwin D. T., Foster J. S., Goddard A. D., Yansura D. G., Vandlen R. L., Wood W. I., Gurney A. L. (2001) IL-17E, a novel proinflammatory ligand for the IL-17 receptor homolog IL-17Rh1. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1660–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamaguchi Y., Fujio K., Shoda H., Okamoto A., Tsuno N. H., Takahashi K., Yamamoto K. (2007) IL-17B and IL-17C are associated with TNF-alpha production and contribute to the exacerbation of inflammatory arthritis. J. Immunol. 179, 7128–7136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Starnes T., Broxmeyer H. E., Robertson M. J., Hromas R. (2002) Cutting edge: IL-17D, a novel member of the IL-17 family, stimulates cytokine production and inhibits hemopoiesis. J. Immunol. 169, 642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishigame H., Kakuta S., Nagai T., Kadoki M., Nambu A., Komiyama Y., Fujikado N., Tanahashi Y., Akitsu A., Kotaki H., Sudo K., Nakae S., Sasakawa C., Iwakura Y. (2009) Differential roles of interleukin-17A and -17F in host defense against mucoepithelial bacterial infection and allergic responses. Immunity 30, 108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Claudio E., Sønder S. U., Saret S., Carvalho G., Ramalingam T. R., Wynn T. A., Chariot A., Garcia-Perganeda A., Leonardi A., Paun A., Chen A., Ren N. Y., Wang H., Siebenlist U. (2009) The adaptor protein CIKS/Act1 is essential for IL-25-mediated allergic airway inflammation. J. Immunol. 182, 1617–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamai Y., Kubota M., Kamai Y., Hosokawa T., Fukuoka T., Filler S. (2001) New model of oropharyngeal candidiasis in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 3195–3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernández-Santos N., Huppler A. R., Peterson A. C., Khader S. A., McKenna K. C., Gaffen S. L. (2013) Th17 cells confer long-term adaptive immunity to oral mucosal Candida albicans infections. Mucosal Immunol. 6, 900–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solis N. V., Filler S. G. (2012) Mouse model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Nat. Protoc. 7, 637–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conti H. R., Whibley N., Coleman B. M., Garg A. V., Jaycox J. R., Gaffen S. L. (2015) Signaling through IL-17C/IL-17RE is dispensable for immunity to systemic, oral and cutaneous candidiasis. PLoS One 10, e0122807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huppler A. R., Verma A. H., Conti H. R., Gaffen S. L. (2015) Neutrophils do not express IL-17A in the context of acute oropharyngeal candidiasis. Pathogens 4, 559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen F., Ruddy M. J., Plamondon P., Gaffen S. L. (2005) Cytokines link osteoblasts and inflammation: microarray analysis of interleukin-17- and TNF-alpha-induced genes in bone cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77, 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruddy M. J., Wong G. C., Liu X. K., Yamamoto H., Kasayama S., Kirkwood K. L., Gaffen S. L. (2004) Functional cooperation between interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha is mediated by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family members. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2559–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miossec P. (2003) Interleukin-17 in rheumatoid arthritis: if T cells were to contribute to inflammation and destruction through synergy. Arthritis Rheum. 48, 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferreira M. C., Whibley N., Mamo A. J., Siebenlist U., Chan Y. R., Gaffen S. L. (2014) Interleukin-17-induced protein lipocalin 2 is dispensable for immunity to oral candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 82, 1030–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iliev I. D., Funari V. A., Taylor K. D., Nguyen Q., Reyes C. N., Strom S. P., Brown J., Becker C. A., Fleshner P. R., Dubinsky M., Rotter J. I., Wang H. L., McGovern D. P., Brown G. D., Underhill D. M. (2012) Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science 336, 1314–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gladiator A., Wangler N., Trautwein-Weidner K., LeibundGut-Landmann S. (2013) Cutting edge: IL-17-secreting innate lymphoid cells are essential for host defense against fungal infection. J. Immunol. 190, 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saijo S., Ikeda S., Yamabe K., Kakuta S., Ishigame H., Akitsu A., Fujikado N., Kusaka T., Kubo S., Chung S. H., Komatsu R., Miura N., Adachi Y., Ohno N., Shibuya K., Yamamoto N., Kawakami K., Yamasaki S., Saito T., Akira S., Iwakura Y. (2010) Dectin-2 recognition of α-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity 32, 681–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trautwein-Weidner K., Gladiator A., Nur S., Diethelm P., LeibundGut-Landmann S. (2015) IL-17-mediated antifungal defense in the oral mucosa is independent of neutrophils. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miossec P., Kolls J. K. (2012) Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11, 763–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Freeman A. F., Holland S. M. (2008) The hyper-IgE syndromes. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 28, 277–291, viii (viii.). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haak S., Croxford A. L., Kreymborg K., Heppner F. L., Pouly S., Becher B., Waisman A. (2009) IL-17A and IL-17F do not contribute vitally to autoimmune neuro-inflammation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luo Z., Lei H., Sun Y., Liu X., Su D. F. (2015) Orosomucoid, an acute response protein with multiple modulating activities. J. Physiol. Biochem. 71, 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakamura K., Ito I., Kobayashi M., Herndon D. N., Suzuki F. (2015) Orosomucoid 1 drives opportunistic infections through the polarization of monocytes to the M2b phenotype. Cytokine 73, 8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Joly S., Eisenbarth S. C., Olivier A. K., Williams A., Kaplan D. H., Cassel S. L., Flavell R. A., Sutterwala F. S. (2012) Cutting edge: Nlrp10 is essential for protective antifungal adaptive immunity against Candida albicans. J. Immunol. 189, 4713–4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rabeony H., Petit-Paris I., Garnier J., Barrault C., Pedretti N., Guilloteau K., Jegou J. F., Guillet G., Huguier V., Lecron J. C., Bernard F. X., Morel F. (2014) Inhibition of keratinocyte differentiation by the synergistic effect of IL-17A, IL-22, IL-1α, TNFα and oncostatin M. PLoS One 9, e101937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hieshima K., Ohtani H., Shibano M., Izawa D., Nakayama T., Kawasaki Y., Shiba F., Shiota M., Katou F., Saito T., Yoshie O. (2003) CCL28 has dual roles in mucosal immunity as a chemokine with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. J. Immunol. 170, 1452–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edgerton M., Koshlukova S. E., Araujo M. W., Patel R. C., Dong J., Bruenn J. A. (2000) Salivary histatin 5 and human neutrophil defensin 1 kill Candida albicans via shared pathways. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 3310–3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nograles K. E., Zaba L. C., Guttman-Yassky E., Fuentes-Duculan J., Suárez-Fariñas M., Cardinale I., Khatcherian A., Gonzalez J., Pierson K. C., White T. R., Pensabene C., Coats I., Novitskaya I., Lowes M. A., Krueger J. G. (2008) Th17 cytokines interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-22 modulate distinct inflammatory and keratinocyte-response pathways. Br. J. Dermatol. 159, 1092–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reich K., Papp K. A., Matheson R. T., Tu J. H., Bissonnette R., Bourcier M., Gratton D., Kunynetz R. A., Poulin Y., Rosoph L. A., Stingl G., Bauer W. M., Salter J. M., Falk T. M., Blödorn-Schlicht N. A., Hueber W., Sommer U., Schumacher M. M., Peters T., Kriehuber E., Lee D. M., Wieczorek G. A., Kolbinger F., Bleul C. C. (2015) Evidence that a neutrophil-keratinocyte crosstalk is an early target of IL-17A inhibition in psoriasis. Exp. Dermatol. 24, 529–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Von Vietinghoff S., Ley K. (2009) IL-17A controls IL-17F production and maintains blood neutrophil counts in mice. J. Immunol. 183, 865–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Acosta-Rodriguez E. V., Rivino L., Geginat J., Jarrossay D., Gattorno M., Lanzavecchia A., Sallusto F., Napolitani G. (2007) Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zielinski C. E., Mele F., Aschenbrenner D., Jarrossay D., Ronchi F., Gattorno M., Monticelli S., Lanzavecchia A., Sallusto F. (2012) Pathogen-induced human TH17 cells produce IFN-γ or IL-10 and are regulated by IL-1β. Nature 484, 514–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bär E., Gladiator A., Bastidas S., Roschitzki B., Acha-Orbea H., Oxenius A., LeibundGut-Landmann S. (2012) A novel Th cell epitope of Candida albicans mediates protection from fungal infection. J. Immunol. 188, 5636–5643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moyes D. L., Naglik J. R. (2011) Mucosal immunity and Candida albicans infection. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011, 346307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]