Abstract

Delayed patient discharge will likely exacerbate bed shortages. This study prospectively determined the frequency, causes and potential cost implications of delays for 83 consecutive patients, who were inpatients for a total of 888 days. 65% of patients experienced delay whilst awaiting a service. 48% of patients experienced delays that extended their discharge date. Discharge delays accounted for 21% of the cohort's inpatient stay, at an estimated cost of £565 per patient; 77% of these hold-ups resulted from delays in the provision of social and therapy requirements. Discharge delays are costly for hospitals and depressing for patients. Investment is required to enable health and social-care professionals to work more closely to improve the patient journey.

Key Words: delayed discharge, patient experience, patient journey, Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) agenda

Introduction

The NHS is increasingly criticised for bed shortages, delayed elective admissions and long waiting lists.1 The number of admissions to secondary care in the UK is growing year-on-year2 because of limited out-of-hours services in primary care, a greater number of patients who expect proactive hospital care and, most significantly, an increasing population of older people. Older patients are often frail and have complex social and healthcare needs, resulting in a prolonged inpatient stay.3

At the same time as hospital admissions have increased, there has been a decrease in the number of hospital inpatient beds.4 This has been off-set by efficiency directives, with a reduction in the average inpatient stay from 11.7 days in 1980 to 6.8 days in 2000.5 One hospital has recently reported a reduction in average inpatient stay to 5.3 days, coincident with the introduction of twice-daily consultant ward rounds.6 Nevertheless, demand frequently outstrips supply. Hospitals are often ‘full’, with deleterious effects that include delayed patient flow, failure of specialty ward-based hospital systems and delayed or cancelled elective admissions.

Bed pressures are increased by ‘delayed discharges’, which exacerbate patients' exposure to hospital-acquired infections, low mood and increasing loss of functional capacity. Remedying such delays would provide both cost savings and better quality of care, in line with the NHS Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) agenda.

The aims of this longitudinal prospective study were to determine the length of inappropriate delay experienced by patients in a general medical ward prior to discharge, to identify common causes of delay and to estimate the financial implications of discharge delays.

Methods

The Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, admits both medical and surgical patients to an acute admissions unit (AAU), from which 60% are discharged home within 48 hours. The remainder are transferred to base wards. The majority of these patients require specialist elderly care that cannot be provided by single organ specialists.

For seven weeks beginning 12 October 2010, all of the patients looked after by the gastroenterology general medicine team, both in their base and in designated out-lying wards, were included in this study. Only prospective data were incorporated in the results.

The duration of inpatient stay and the time at which a patient was ‘medically fit for discharge’ were recorded. The latter was prospectively agreed in unison by the consultant and specialist registrar, and confirmed at the next multi-disciplinary team meeting. If a patient became unwell after being declared medically fit, delays associated with all of the periods of being medically fit were summated. The medical records for every patient in the study were reviewed and staff interviews conducted each day to identify any delay. The data were recorded daily during weekdays and on Mondays following each weekend.

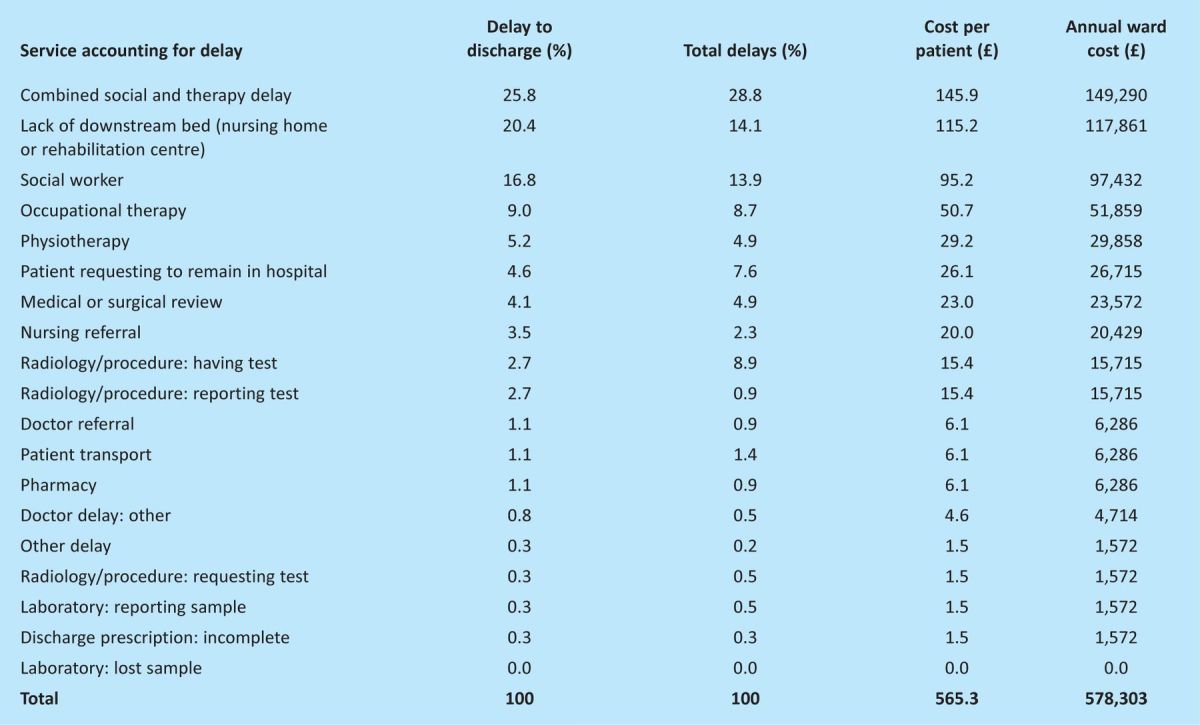

A pilot study was used to define the reasons to which delays could be attributed (Table 1). ‘Combined social and therapy delay’ describes hold-ups affecting ‘medically fit’ patients who were awaiting review from more than one service—physiotherapy, occupational therapy or social services—for whom it was not possible to determine which of these three services was/were preventing discharge. A delay was recorded for each day during which these patients were not seen or, in the case of social services, during which no progress was made.

Table 1.

Causes of total delays and delay to discharge, and the associated patient and ward costs resulting from discharge delays.

The day was split into two time periods (9.00am–1.00pm and 1.00–5.00pm). If the service occurred in the same or next time period as the request, then no delay was recorded. A half-day delay was attributed for every subsequent time period lag in the service. Weekend delays were included in this study, thus a service requested on Friday afternoon that occurred on Monday morning would be recorded as a two-day delay.

‘Total delay’ was defined as the sum of all delays. Delays were summated if services were delayed concurrently. ‘Delay to discharge’ was defined as the sum of delays that prolonged a patient's hospital stay; none were concurrent. It excluded the provision of services needed to enable a medically fit patient's discharge (eg physiotherapy).

The data were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) but had a strong positive skew; hence, median values are provided. Mean values are provided to illustrate the effect of patients whose admissions were prolonged. Percentages are quoted to one decimal place. All calculations were performed using Graphpad InStat for Macintosh v3.1a (Graphpad Software Inc, California, USA).

The costs of each day's delay was calculated using the DOH reference cost of £255.7 Where 2010 figures were not available, the most recent published data were used and multiplied by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for each discrepant year.

Results

The complete dataset included information from 83 patients. Their median age was 71 years (range 21–98); 53 were female. Thirteen of the patients included in the study were still inpatients at the time of study closure; of these, nine were ‘medically fit for discharge’. Five patients died whilst enrolled in the study; none of these had been declared ‘medically fit for discharge’.

In total, 54 of the 83 patients (65.1%) experienced a delay while waiting for a service. Forty of the 83 (48.2%) patients experienced a delay that extended their discharge date.

A total of 888 inpatient days were included in the study. The total number of ‘acutely ill’ days was 649 (73.1%). The mean number of ‘acutely ill’ days per patient was 8.3 (median = 5). The total number of ‘medically fit’ days was 239 (26.9%). The mean number of ‘medically fit’ days per patient was 3.1 (median = 1).

Of the 888 bed days, the number of days affected by a delay (‘total delay’) was 288 (32.4%). The mean ‘total delay’ per patient was 3.5 days (median = 0.5).

The number of days delay that prevented timely discharge from hospital (‘delay to discharge’) was 184 days (20.7%). The mean duration of ‘delay to discharge’ per patient was 2.2 days (median = 0.0).

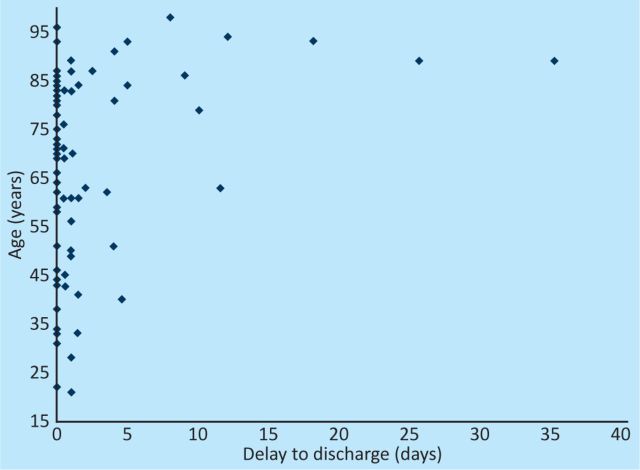

There was a trend towards an increased number of patients experiencing longer delays with increasing patient age. Nine of the 10 patients whose discharge was delayed by more than five days were over the age of 75 years (Fig 1). The percentage total delay, delay to discharge and associated attributable costs are shown (Table 1).

Fig 1.

The relationship between delay to discharge and patient age.

Thirteen patients suffered a delayed discharge that included one or more weekends, comprising a total of 52 weekend days (5.9%), of which 42 (4.7%) were attributed to reduced weekend services.

Discussion

Delays that interfere with a safe discharge from medical wards are an area that has received relatively little attention because UK government targets have focused on admission rather than discharge. Little analysis of these delays has been published recently, and there is considerable heterogeneity amongst older studies, many of which have methodological flaws.8 Therefore, we performed an in-depth prospective study to define the causes and financial cost of delays in discharges from the general medical wards of a metropolitan teaching hospital. We show that the majority of patients experienced delays and that these delays interfered with the discharge of half the patients. One-third of these delays, accounting for one-fifth of the cohort's inpatient stay, were avoidable. These findings are similar to those of both a recent UK study and a large US study, the latter finding that 13.5% of bed days were inappropriate and that 63% of delays had non-medical reasons.10

We defined a half-day delay as allowable, believing that the NHS should aspire to provide very efficient healthcare with standards similar to those of private providers. We recognise that arranging socially complicated discharges can take a long time, and therefore that discharge planning should start before a patient is deemed medically fit. Often, however, social services only accept a referral and start discharge planning once a patient is deemed medically fit.

The Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (AEP)11 was designed and validated in the US as a technique for evaluating unnecessary days of hospital care. However, utilisation tools such as the AEP have a low level of validity when compared to expert review12 and do not necessarily add to clinical judgement.13 Therefore, we chose to rely on clinical judgement to determine the point at which a patient was medically fit for discharge, mirroring what actually occurs in clinical practice. In a completely efficient system, this would be the point of discharge from the hospital. Subsequent inappropriate delays were summated to determine the ‘delay to discharge’. They accounted for 21% of the total inpatient stay for this ward-based cohort.

Most delayed discharges resulted from combined social and therapy delay, or social worker or downstream bed delays. Similar reasons for discharge delays have been reported previously9,14,15. Untimely social worker review was a significant component, accounting for 16.8% of delayed discharge days and costing a ward £97,432 annually. The reasons for this need to be understood. They probably include both inadequate numbers of trained social workers and the added complexity of trying to arrange discharges with limited downstream facilities. This issue is unlikely to be resolved while secondary and social care budgets are subject to competition.

On receiving Section 2 of The Continuing Health Care form, notifying of a planned discharge of a medically fit patient, social services are allowed 72 hours to assess and arrange care. The Community Care (Delayed Discharges) Act of 2003 enabled hospital trusts to fine social services (termed ‘reimbursement’) if a patient stayed in hospital beyond this time. This disincentive is imperfect. The daily reimbursement was set at £120 per day for London and the South-East and £100 for other parts of England. This levy was more expensive than hospital care in 2003, yet the charge has not been increased since inception. As of 2010, it costs £99 and £71, respectively, to provide 24 hours' care in a standard nursing and residential home.16 Daily residential intermediate care costs £18617 and daily acute medical care £255.7 Two-thirds of trusts do not implement the reimbursement levy,18 perhaps as cooperation is deemed to be more effective in a resource-poor system.

The NHS Plan,19 and the National Service Framework for Older People,20 identify intermediate care as a key method for avoiding unnecessary hospital admissions and delayed discharges. Between 1999 and 2004, £900 million was spent on increasing the number of available places by 150,000. The government reported that this resulted in a 64% reduction in delayed discharge from acute hospitals.21 Despite this, our study shows that 18% of delayed discharge days are the result of the lack of an appropriate downstream bed (rehabilitation, care home or other). The older population is the fastest-growing age demographic, with the ‘very old’ (those over 80) being the fastest-growing subgroup,22 so investment in intermediate care will need to increase, though this seems unlikely in the current financial climate.

In a pre-defined sub-analysis, we reviewed data from patients with a delay to discharge greater than the 90th percentile. Their median delay to discharge was 11.5 days (mean 14.9), compared to zero days (mean 0.7 days) below the 90th percentile. This highlights the importance of identifying potential long-stay patients. A Swiss study derived and validated a simple score that can be used at 24 h or 72 h to predict general medical patients who should receive early discharge planning.23 Similar scoring systems should be validated in UK populations so that proactive discharge planning can be provided to those for whom it is most needed.

A total of 52 delayed discharge days occurred at weekends, 42 days of them resulting from reduced weekend services. This equates to an annual cost of £132,004 for a 30-bed ward. Recently, the RCP recommended that consultants review ward patients at weekends,24 which may help to reduce the excess mortality that occurs at this time.25 However, our study suggests that these weekend ward rounds could not achieve cost neutrality by enabling weekend discharges because many discharges would be prevented by the lack of social service assessment.

Summary of findings.

The majority of patients experienced delays

Delays interfered with the discharge of half of the patients

Avoidable delays occurred one-third of the time

Avoidable delays accounted for one-fifth of the cohort's inpatient stay

Extended inappropriate discharge delays occurred in those older than 75 years

Delays to discharge cost a 30-bed ward more than £0.5 million annually

Discharge delays are costly for hospitals and depressing for patients. We have shown that these delays are common and have defined their major causes. We counsel caution in appropriating blame, remembering that a slow but safe and well-planned discharge is preferable to a swift sub-optimal one.26 Solutions will be multi-faceted but would seem likely to include closer personalised working relationships between hospital and social service staff and investment to streamline the patient journey. Effective solutions will prevent delays in patient flow through both the acute admissions unit and base wards, will reduce iatrogenic delays, and will probably provide financial savings. They will mean that the patient rather than the organisation is the priority, and the denigrating term ‘bed-blocker’ will no longer be used.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. They also thank Sundhiya Mandalia, who provided statistical advice.

References

- 1.Guardian Newspaper August 18, 2011. NHS waiting times soar as doctors blame cuts in hospital budgets. www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/aug/18/nhs-waiting-times-soar-cuts [Accessed 2 July 2012]

- 2.Department of Health. NHS inpatient elective admission events and outpatient referrals and attendances, quarter ending December 2010. London: DH, 2011. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_124553 [Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sklar D. Length of hospital stay for elderly people is substantially higher in the NHS compared with Kaiser Permanente and US Medicare programmes. Evidence-based Healthcare & Public Health 2004;8:113–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. Report explains drop in hospital bed numbers. London: DH, 2006. www.dh.gov.uk/en/MediaCentre/DH_4135246 [Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson M, Black D. Average length of stay, delayed discharge, and hospital congestion: A combination of medical and managerial skills is needed to solve the problem. BMJ 2002;325:610–1. 10.1136/bmj.325.7365.610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad A, Purewal TS, Sharma D, Weston PJ. The impact of twice-daily consultant ward rounds on the length of stay in two general medical wards. Clin Med 2011;11:524–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. 2009–10 reference costs publication. London: DH, 2011. www.dh.gov.uk/dr_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_123501.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasby J, Littlechild R, Pryce K. All dressed up but nowhere to go? Delayed hospital discharges and older people. J Health Serv Res Policy 2006;11:52–8. 10.1258/135581906775094208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carey MR, Sheth H, Braithwaite RS. A prospective study of reasons for prolonged hospitalizations on a general medicine teaching service. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:108–15. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jasinarachchi KH, Ibrahim IR, Keegan BC, et al. Delayed transfer of care from NHS secondary care to primary care in England: its determinants, effect on hospital bed days, prevalence of acute medical conditions and deaths during delay, in older adults aged 65 years and over. BMC Geriatr 2009;9:4. 10.1186/1471-2318-9-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gertman PM, Restuccia JD. The appropriateness evaluation protocol: a technique for assessing unnecessary days of hospital care. Med Care 1981;19:855–71. 10.1097/00005650-198108000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalant N, Berlinguet M, Diodati JG, et al. How valid are utilization review tools in assessing appropriate use of acute care beds. CMAJ 2000;162:1809–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler JS, Barrett BJ, Kent G, et al. Detection and classification of inappropriate hospital stay. Clin Invest Med 1996;19:251–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter ND, Wade DT. Delayed discharges from Oxford city hospitals: who and why. Clin Rehabil 2002;16:315–20. 10.1191/0269215502cr496oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith HE, Pryce A, Carlisle L, et al. Appropriateness of acute medical admissions and length of stay. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1997;31:527–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anon. Laing & Buisson's annual review of the UK elderly care market. London: Laing & Buisson, 2010. Lawww.laingbuisson.co.uk/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=7NqbssCOgKA%3D&tabid=558&mid=1888 [Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glasby J, Martin G, Regen E. Older people and the relationship between hospital services and intermediate care: results from a national evaluation. J Interprof Care 2008;22:639–49. 10.1080/13561820802309729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollock A, McCoy D. Unblocking ‘bed blocking’. Swindon: ESRC, 2011. www.publicservices.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/v2_pollock.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Her Majesty's Government. The NHS Plan. A plan for investment. A plan for reform. London: DH, 2000. www.dh.gov.uk/dr_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_118522.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health. The National Service Framework for Older People. London: DH, 2001. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4003066 [Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health. Our health, our care, our say: a new direction for community services. London: DH, 2006. www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm67/6737/6737.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Government's Actuary Department. The Aging Population. London: ONS, 2010. ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-229866[Accessed 2 July 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louis-Simonet M, Kossovsky MP, Chopard P, et al. A predictive score to identify hospitalized patients' risk of discharge to a post-acute care facility. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:154. 10.1186/1472-6963-8-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patients deserve better out of hours care, says RCP president , 2010. http://pressrelease.rcplondon.ac.uk/Archive/2010/Patients-deserve-better-out-of-hours-care-says-RCP-President [Accessed 2 July 2012]

- 25.The Guardian Newspaper November 28, 2011. Hospitals told to investigate higher weekend death rates. www.guardian.co.uk/society/2011/nov/28/hospitals-higher-weekend-death-rates?newsfeed=true [Accessed 2 July 2012]

- 26.Vetter N. Inappropriately delayed discharge from hospital: what do we know? BMJ 2003;326:927–8. 10.1136/bmj.326.7395.927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]