Abstract

Many governments in Europe, either of their own volition or at the behest of the international financial institutions, have adopted stringent austerity policies in response to the financial crisis. By contrast, the USA launched a financial stimulus. The results of these experiments are now clear: the American economy is growing and those European countries adopting austerity, including the UK, Ireland, Greece, Portugal and Spain, are stagnating and struggling to repay rising debts. An initial recovery in the UK was halted once austerity measures hit. However, austerity has been not only an economic failure, but also a health failure, with increasing numbers of suicides and, where cuts in health budgets are being imposed, increasing numbers of people being unable to access care. Yet their stories remain largely untold. Here, we argue that there is an alternative to austerity, but that ideology is triumphing over evidence. Our paper was written to contribute to discussions among health policy leaders in Europe that will take place at the 15th European Health Forum at Gastein in October 2012, as its theme ‘Crisis and Opportunity – Health in an Age of Austerity’.

The origins of the financial crisis

It is now almost five years since the onset of the most severe economic crisis to hit Europe since the 1930s. For many people in the UK, its onset was signalled by scenes of depositors queuing outside branches of Northern Rock, once a successful building society that had converted itself into a bank and expanded rapidly into the global financial markets. Unfortunately, with hindsight it is now clear that the expansion of Northern Rock was too rapid. As a building society, it raised money from its depositors to lend to those seeking to purchase a house, but only if borrowers could demonstrate that they had the ability to keep up the repayments. Its loans were limited by what it could attract in deposits. However, during the 1990s, freed from regulation by successive governments that were each competing to be seen as more business friendly, Northern Rock borrowed massively on the global capital markets. These vast sums were offered as loans to anyone wanting to buy a house, with only the most cursory checks as to whether they could repay them. Then, to hedge against this risky proposition, the bank wrapped up the expected stream of future repayments into complex financial instruments that it sold on the global markets. Those buying these ‘securitised loans’ realised that they were risky but they would hedge their bets, constructing even more complex financial instruments.

Unfortunately, as it soon became clear, few, if any, of those involved in these complex financial webs really understood what they were doing.1 An increase in interest rates in the USA during the mid-2000s, where the same had been happening, meant that people could no longer repay the loans. The entire system rapidly unravelled, leaving those countries most dependent on financial services, such as the UK, facing the double burden of a collapse in tax revenues from the financial sector while simultaneously having to inject large sums of money into the retail banks, which were by now inextricably entwined with their much riskier investment arms, to stave off a banking collapse.2 Those countries that had continued to invest in their manufacturing industry and had lower rates of home-ownership, such as Germany, were much less exposed. Elsewhere, there were some specific risk factors for economic collapse. In Greece, for example, it became clear that the published economic data had, for many years, been falsified3 and the country faced a severe debt crisis, largely as a result of a failure to collect taxes. A neo-liberal government in Iceland had also deregulated the financial sector, allowing a small group of individuals bent on individual enrichment, some of whom are now serving prison sentences, to engage in reckless behaviour that brought the country to the brink of bankruptcy.4 However, fundamentally, the problem was one of a failure to regulate the financial institutions, a point that it is necessary to reiterate as it often seems to have been forgotten. In most countries, including the UK, the problem was not one of unsustainable debt. Indeed, UK debt as a fraction of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at the onset of the crisis was lower than in France or Germany, and far lower than it had been historically.2

Possible responses

The unresolved question was what to do about it. Unfortunately, economists were divided.5 Monetarists, who had argued that growth would be stimulated by reducing interest rates, found that little could be done when interest rates fell to almost zero. The next step was to print money, in a process known as quantitative easing, where the money was issued to the major banks. Unfortunately, rather than lend this additional money, the banks used it to rebuild their balance sheets and pay large bonuses to their staff, so that small and medium companies were starved of investment funds. Another group, the Keynesians, subscribed to the policies advocated by their namesake in the aftermath of the Great Depression, when John Maynard Keynes argued that, by taking care of unemployment, the economy would look after itself: the need was to stimulate consumption and demand to prevent a negative spiral of declining confidence, lower spending, and more job losses and firm bankruptcies. This is, in effect, the policy pursued by President Obama, with large-scale stimulus packages (although the magnitude has been debated), including substantial investment in the automobile industry. A third group of supply-side economists argued that the problem was over-regulation, or ‘red tape’, and advocated massive deregulation. They believed that abolition of employment rights would enable wages to fall and unwanted labour to be shed, allowing firms to compete better in a global market. However, a new school of thought emerged, labelled ‘austerions’ by the economics Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman.6 They called for a massive shrinking of the state, arguing that the European welfare state was unaffordable. They included politicians in the UK, as well as some countries in the Eurozone, as well as the ‘troika’ comprising the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Given that all economic crises are in some ways different, a case could be made for any of these approaches and the ultimate choice, on the evidence then available, was largely down to political ideology. Indeed, in a prescient book published just before the onset of the crisis, Naomi Klein had predicted that neoliberal politicians opposed to what they termed ‘big government’ would use such an event as an opportunity to pursue their political objectives in a way that would otherwise not be possible, making the case that there was no alternative.7

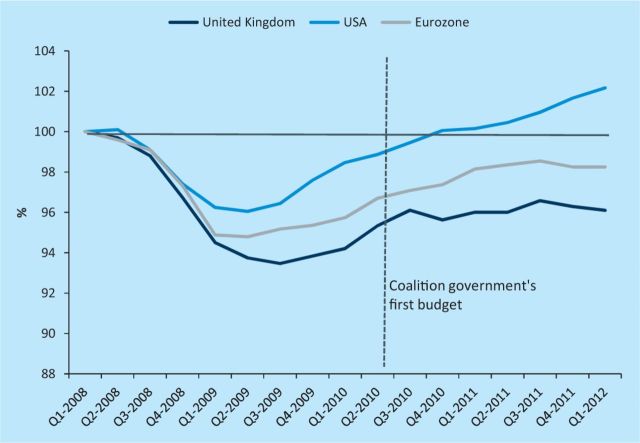

Five years on, the results of the ‘great austerity experiment’ are at last becoming clear (Fig 1). In the USA, where a Keynesian approach was adopted, the economy has recovered and is now on a sustained upward trajectory. The Eurozone is experiencing mixed fortunes. Some countries, such as Germany, are also experiencing sustained growth, but those that adopted stringent austerity policies, such as Ireland, Greece, Spain and Portugal, have yet to recover. Iceland, one of the worst affected countries, held a referendum on austerity; 93% of the population rejected it and, so far, austerity has been delayed and limited. As a result, Iceland has had much better economic performance than the latter group of austerity cases (in part, enabled by its ability to devalue its currency and, in so doing, boost fishing exports). Paradoxically, the credit-rating agencies, which were once in the vanguard of calls for austerity, are now downgrading Italian banks explicitly because of concerns that austerity is choking off growth.8 The UK did make an initial recovery but there too the imposition of stringent austerity measures by the newly elected coalition government in 2010 arrested it. This evidence has not gone unnoticed and, in a series of elections across Europe in 2012, voters have rejected austerity and elected politicians offering an alternative, most notably in France but also in German regional elections. Yet their reasons for doing so are not simply because these policies have failed to fix the economy. They are also rejecting them because they are seeing the signs of the human cost that they incur, something that many politicians have sought to ignore.

Fig 1.

Change in gross domestic product (GDP), indexed on Quarter 1, 2008.

Source: calculated from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data on quarterly change in GDP.

The consequences for health

Until recently, the human cost of austerity policies was largely invisible. One important reason was the lack of relevant data. In marked contrast to financial data, some of which are available instantaneously and others, such as economic growth, within a few weeks, data on mortality in many countries are delayed by several years. Thus, it is only now that the tragedy that is afflicting parts of Europe is becoming apparent.

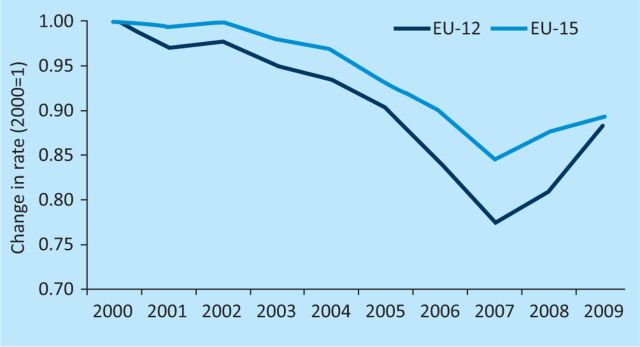

On the basis of experience in previous economic crises, it was anticipated that suicides would increase and road traffic deaths would fall.9 This is exactly what has happened. In those countries from which data are available, a long-term decline in suicides reversed in 2008 and is now increasing (Fig 2).10 The situation with traffic deaths is more complicated. Previously, the decline in vehicle miles travelled meant that deaths fell. This tended to compensate for the increase in suicides. However, deaths on the roads in many countries are now at very low levels, offering little scope for further improvements. Consequently, the reductions are mainly seen in those European countries, such as the Baltic States, where such deaths are still common.10

Fig 2.

Trends in suicides in Europe (indexed on the rate in 2000).

Source: WHO mortality database.

However, there is evidence that an increase in suicides in an economic crisis is not inevitable. Research on economic fluctuations in Western Europe over the past three decades showed how those countries with strong systems of social protection were able to maintain long-term declines in suicide rates despite rapid increases in unemployment.11 The most important factor appeared to be the existence of active labour market programs, designed to get people back into employment as quickly as possible, and typically including youth training, exchange of information on vacancies and measures to support disabled people in the workforce. Unfortunately, programs such as these are being cut in many countries at the present time.

So far, Greece appears to be the most severely afflicted European country. There are worrying signs of increases in several infectious diseases, including malaria.12 However, the greatest concern relates to HIV infections, which have risen markedly in the past year, with the epidemic concentrated among a growing number of intravenous drug users.13 Data from elsewhere are still limited, but one study has shown a marked increase in attendances at Spanish general practitioners by those with mental disorders, especially depression.14

In the absence of up-to-date statistics, the unfolding tragedy is most visible following a series of high-profile suicides, such as the pensioner who shot himself dead on the steps of the Greek parliament or among the widows who have protested by marching on tax offices in Italy in memory of their husbands who committed suicide.

There is a marked contrast between the energy that national governments put into collecting economic statistics and what they put into gathering and analysing health data. Despite detailed media coverage, in particular by the New York Times, the silence from European health ministers on the human consequences of austerity is striking. Moreover, the absence of any serious consideration of the consequences of austerity policies for population health from the documents of the troika, charged with enforcing austerity in those countries undergoing bailouts, is notable, even as they are imposing major changes to national health systems.15

The consequences for healthcare

An inability to access healthcare will have adverse consequences at the best of times. However, the consequences are particularly worrying in industrialised countries that have had a functioning system in place. There will be many people suffering from chronic diseases who are kept alive by regular therapy, whether for hypertension, diabetes, or even cancer. A breakdown in the supply of essential medicines could be fatal.

One of the earliest actions by the previous Greek government was to enforce a reduction in the price that it would pay for pharmaceuticals, with hopes of rooting out longstanding issues of corruption. Unfortunately, it had the opposite effect: it led to significant shortages in many parts of the country. This was exacerbated by closures of health facilities and a recent analysis showed a significant increase in the number of people who were not seeking care even though they believed it to be medically justified. Increasing numbers of Greeks are now depending on street clinics once used to treat undocumented migrants.

In Spain, health policy is primarily the responsibility of the 17 regions, although within a financial framework determined by the national government. Hence, there are considerable regional variations in reforms, although at both levels the policy changes have been driven by finance ministries with limited involvement by health ministries or professionals. As a consequence, the reforms have been described as incoherent, with considerable scope for unplanned adverse consequences.16 Catalonia has been in the forefront of the austerity programme, with swingeing cuts to staffing and investment.17 Recently, the newly elected right-wing government has seized the opportunity offered by the crisis to introduce a major reform to the healthcare system.18 It did this by royal decree, thus avoiding the problems that it would have faced if it had enacted primary legislation. The reforms have fundamentally reworked the healthcare system from a basis of entitlement based on residence to a system where entitlement is based on employment. This risks some of the damaging effects observed in the USA, where entitlement is largely linked to jobs, including the exclusion from healthcare of large numbers of undocumented migrants and young people who have never been employed, a potentially serious situation in Spain where over half of all youth are unemployed.

The troika has imposed major cuts to the Portuguese health budget, as well as large increases in the rate of co-payment for many services as part of its conditions for a financial rescue package.19 For example, attendance at an emergency department in a major hospital now incurs a cost of 20 instead of 9.60 previously. Several services, such as nurse consultations, have been subject to user charges for the first time. Political and media commentators have attributed a peak in deaths in early 2012 to the austerity policies, but the actual reasons remain contested.

The Italian government has also adopted several cost containment measures, many accelerating longstanding efforts to reduce expenditure.20 They have focused on hospital capacity, with the 2010–2012 Health Pact between the central government and the regions, who are responsible for the delivery of healthcare, requiring a reduction in the number hospital beds, from 4.5 to 4 per 1,000 population, fewer hospital admissions, based on appropriateness criteria to reduce unnecessary admissions, and shorter lengths of stay. Those regions with the highest debt levels were required to propose plans for implementation before other regions. The policy also introduces co-payments, of 10 per visit to a specialist and 25 for those aged over 14 visiting an emergency department where this is considered inappropriate. However, regions have flexibility in introducing these measures. A 12.5% reduction in the prices paid for generic drugs was also imposed.

Discussion

Governments in the UK and the Eurozone were faced with a choice when the financial crisis hit in 2008. They could have followed the example of the USA and launched a fiscal stimulus using funds raised by the European Central Bank, seeking to boost growth and thus escape from recession. Instead, they engaged in austerity programmes that, in those countries most severely afflicted by the initial crisis, have choked off any growth. The argument that there was no alternative is now being rejected by voters across Europe, even in Germany, where the government has been among the strongest advocates of austerity. Voters recognise that the experiment with austerity has failed, despite the increasingly incredulous claims of some of their political leaders.

The European public are not only questioning the competence of these politicians, but are also asking why they have failed to address the fundamental causes of the crisis, the deregulation of financial markets,21 especially in the wake of the loss of US$2 billion by a single trader in JP Morgan Chase, a company that had been lobbying actively against even the most minimal restrictions on banks and whose chief executive had initially dismissed the loss as a ‘tempest in a teapot’.22

Some measures that have been taken to reduce health expenditures in response to the crisis can be justified. A reform to public procurement developed by the Greek government under the aegis of the troika, has streamlined a previously inefficient system.23 It clearly makes sense to treat patients outside hospitals where this is appropriate. However, that assumes that there are alternative facilities available, which in many southern European countries where social care has largely been undertaken by families is unlikely to be the case. It is also sensible to encourage generic prescribing, as in Spain. However, other reforms are not supported by evidence, such as the introduction of co-payments, which will fail to discriminate between medically necessary and unnecessary utilisation,24,25 leaving aside the high transaction costs of collecting them. The situation in Greece and in some parts of Spain is especially alarming, with media accounts of health systems nearing collapse.26

For many months, the political and financial aspects of the crisis have filled the headlines. However, behind those headlines, there are many individual human stories that remain untold. They include people with chronic diseases unable to access life-sustaining medicines, persons with rare diseases who are losing income support and forced to care for themselves, and those whose hopes of a better life in the future have been dashed see no alternative but to commit suicide. So far, the discussion has been limited to finance ministers and their counterparts in the international financial institutions. Health ministers have failed to get a seat at the table. As a consequence, the impact on the health and wellbeing of ordinary people was barely considered until they made their feelings clear at the ballot box.

Throughout history, physicians have had an honourable role in placing the health of their fellow citizens on the political agenda, exemplified by the work of Rudolf Virchow in the typhus epidemics in Silesia during the 19th century.27 He famously said that ‘medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine…has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution…The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and social problems fall to a large extent within their jurisdiction.’ A growing number of economists are calling for a reversal of austerity.28 European physicians should add their voices to them. Virchow's words are as relevant today as they ever were.29

References

- 1.Stiglitz JE. Freefall: Free Markets and the Sinking of the Global Economy. London: Penguin, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M, Suhrcke M. Responding to the economic crisis: a primer for public health professionals. J Public Health 2010;32:298–306. 10.1093/pubmed/fdq060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rauch B, Göttsche M, Brähler G, Engel S. Fact and Fiction in EU-Governmental Economic Data. German Economic Review 2011;12:243–255. 10.1111/j.1468-0475.2011.00542.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sigurgeirsdóttir S, Wade RH. Le Monde Diplomatique 2011. Iceland's loud no. mondediplo.com/2011/08/02iceland [Accessed 31 May 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krugman P. How did economists get it so wrong? NY Times 2009. www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all [Accessed 31 May 2012]

- 6.Krugman P. Myths of austerity. NY Times 2010. www.nytimes.com/2010/07/02/opinion/02krugman.html [Accessed 31 May 2012]

- 7.Klein N. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. London: Allen Lane, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.BBC Italian banks have credit ratings cut by Moody's, 2012. www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-18067581 [Accessed 31 May 2012]

- 9.Stuckler D, Meissner C, Fishback P, et al. Banking crises and mortality during the Great Depression: evidence from US urban populations, 1929–1937. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:410–419. 10.1136/jech.2010.121376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, et al. Effects of the 2008 recession on health: a first look at European data. Lancet 2011;378:124–1259 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61079-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, et al. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet 2009;374:315–323. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61124-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danis K, Baka A, Lenglet A, et al. Autochthonous Plasmodium vivax malaria in Greece, 2011. Euro Surveill 2011;16:19993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Papanicolas I, et al. Health effects of financial crisis: omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet 2011;378:1457–1458. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61556-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gili M, Roca M, Basu S, et al. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Publ Health 2012. 10.1093/eurpub/cks035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fahy N. Who is shaping the future of European health systems? BMJ 2012;344:e1712. 10.1136/bmj.e1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gené-Badiaa J, Gallob P, Hernández-Quevedoc C, García-Armestod S. Spanish health care cuts: penny wise and pound foolish? Health Policy 2012;106:23–28. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia Rada A. Wages are slashed and waiting lists grow as Catalonia's health cuts bite. BMJ 2011;343:d6466. 10.1136/bmj.d6466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rada Garcia A. New legislation transforms Spain's health system from universal access to one based on employment. BMJ 2012;344:e3196. 10.1136/bmj.e3196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barros PP. Health policy reform in tough times: the case of Portugal. Health Policy 2012. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giulio de Belvisa A, Ferrè F, Specchia ML, et al. The financial crisis in Italy: implications for the healthcare sector. Health Policy 2012;106:10–16. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krugman P. Why we need to regulate Wall Street. NY Times 2012 (15 May):6.

- 22.Rushe D, Treanor J. SEC launches review after JP Morgan chief reveals $2bn trading loss. Guardian 2012. www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/may/10/jp-morgan-market-loss-hedging [Accessed 31 May 2012]

- 23.Kastaniotia C, Kontodimopoulosa N, Stasinopoulosa D, et al. Public procurement of health technologies in Greece in an era of economic crisis. Health Policy 2012. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA 2007;298:61–69. 10.1001/jama.298.1.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brook RH, Ware JE, Jr, Rogers WH, et al. Does free care improve adults' health? Results from a randomized controlled trial. N Engl J Med 1983;309:1426–1434. 10.1056/NEJM198312083092305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daley S. Fiscal crisis takes toll on health of Greeks. NY Times 2011. www.nytimes.com/2011/12/27/world/europe/greeks-reeling-from-health-care-cutbacks.html?pagewanted=all [Accessed 31 May 2012]

- 27.Reilly RG, McKee M. ‘Decipio’: examining Virchow in the context of modern ‘democracy’ Public Health 2012;126:303–307. 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stiglitz J. Austerity – Europe's man-made disaster. Social Europe Journal. 2012. www.social-europe.eu/2012/05/austerity-europes-man-made-disaster [Accessed 31 May 2012]

- 29.Stuckler D, McKee M. There is an alternative: public health professionals must not remain silent at a time of financial crisis. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:2–3. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]