Abstract

The management of heart failure has evolved to become a multidisciplinary affair. Constraints of time and resources limit the amount of counselling that is given to heart failure patients in hospital and, with the advent of community heart failure specialist nurses, there is a trend to move more of these services into the community. Most heart failure patients are elderly and may find the information given to them, at the time of diagnosis and later on at home by heart failure nurses, difficult to grasp. In this study, patients’ perspectives of a diagnosis of heart failure, their understanding of the diagnosis as well as what being diagnosed with heart failure means to them were recorded. Patients were questioned on whether the news of the heart failure diagnosis was broken to them in a sympathetic manner and how they felt about the information provided at diagnosis.

Key Words: counselling, heart failure, patient information, prognosis

Introduction

Heart failure is a serious condition with a poor prognosis. It is also a condition where the incidence and prevalence is increasing worldwide, partly as a result of an ageing population. It is often not recognised that the mortality of severe heart failure is worse than that of several cancers such as breast, bladder and prostate.1 Similarly, it is not clear whether patients suffering from heart failure actually appreciate the seriousness of their condition.2

Heart failure has a devastating effect on an individual's quality and length of life, and patients are at risk of sudden death from fatal arrhythmias.3 Studies have shown that almost half of all deaths in patients with heart failure are sudden.4 Good medical practice involves informing the patient of the true nature and prognosis of the condition. This poor prognosis is often not appreciated by the patient or the physician and even when the physician is aware, there may be reluctance in informing patients of this poor prognosis unless directly asked about it.2

The inception of the heart failure nurse specialist (HFN) and hospital-based heart failure clinic has led to a number of potential interactions with different healthcare professionals for patients in a variety of settings. Some have a view that the HFN might be better equipped to deal with informing patients of the nature and poor prognosis of heart failure rather than the clinician looking after the patient as they have more frequent interactions with the patient and generally build a better rapport with them. Similarly, patients may feel more at ease with the HFN in asking questions.5

In this study, the patient's perspective of the diagnosis and prognosis of heart failure and whether this was related to the health professional providing the information was recorded. The study also established which healthcare professionals would be best suited to deliver prognostic information and whether a positive or negative attitude to diagnosis is related to the professional who delivers it.

The model of heart failure diagnosis in Coventry is via a weekly, one-stop diagnostic clinic conducted at the University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) NHS Trust. Subsequent care of those diagnosed with heart failure in this clinic is continued through hospital-based, nurse-led up-titration clinics and home visits by the HFNs. Each patient receives a home visit following the diagnosis made in the clinic. At this visit the HFN discusses the diagnosis and all aspects of the disease in detail and provides written information from the British Heart Foundation on heart failure and living with the condition.

Methodology

To answer the questions listed above a questionnaire was devised (available from the author upon request). It was designed around simple nominal data and agreement scaling using a Likert type scale to facilitate the quantitative measurement of the data. Some responses in the questionnaire invited comment from participants.

A postal questionnaire format was used as this avoided the potential for interview bias. In addition, time constraints also inhibited the use of the interview technique as a tool. By using a postal questionnaire format it was possible to elicit responses from a far larger population.

Patients with a diagnosis of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) were identified from the UHCW NHS trust heart failure database. All patients with a confirmed diagnosis were eligible for the study. Following identification of the patients, the HFN team was asked to eliminate patients who, in their opinion, were not well enough to approach with reference to participation in the study.

Each eligible patient was identified and a pack was mailed to them containing the questionnaire, a covering letter and a consent form. Patients were requested to return the signed consent form and questionnaire in the stamped addressed envelope provided. Non-return of the forms was interpreted as refusal to consent to the study.

Prior to mailing, hospital systems and strategic tracing was carried out to ensure that packs were not sent inappropriately. The responses to the questions that were about knowledge or information were compared to the information that is generally given to patients by the HFNs.

The study was accepted by the local hospital ethics committee and was performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Results

For the purpose of the study 218 patients were sent the questionnaire. All had a confirmed diagnosis of LVSD by echocardiogram and were registered on the UHCW NHS trust database. Entries on the database ran from 1999 to the present day. A total of 90 responses were received (response rate of 41%). A second mailing was not deemed necessary as it was felt that the number of further responses would be insignificant. The age range of the sample was from 43 to 87 years of age. The median age was 71. There were 61 men (68%). The majority of patients were Caucasian (96%). South Asians constituted 3% while Afro-Caribbean patients accounted for 1% of the total cohort.

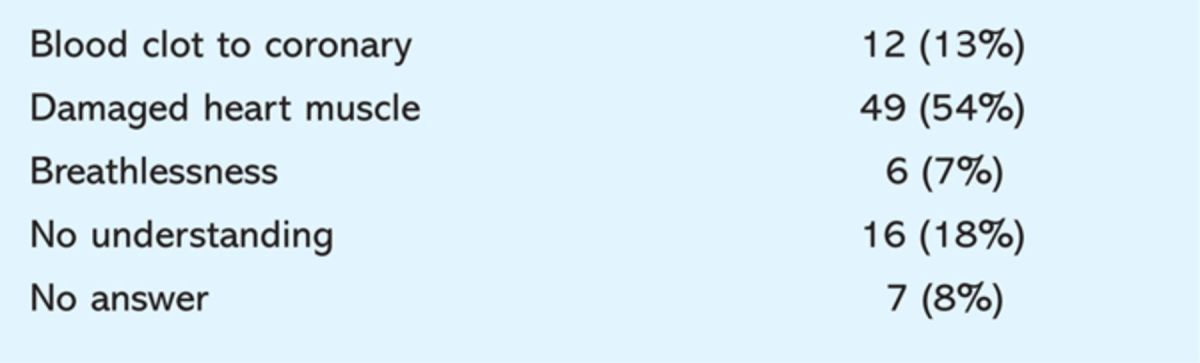

Tables 1 to 8 summarise the patients’ responses. About half of the patients surveyed (54%) felt that heart failure was due to a weakness of the heart muscle and 13% felt it was due to a blood clot to the coronary. Nearly a fifth (18%) felt that they had no understanding of the aetiology (Table 1). Almost half of the cohort felt that they did not understand the meaning of the term ‘heart failure’ at the time of diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patients understanding, in their own words, of the term ‘heart failure’ at the time of the survey (months after diagnosis was made). Responses have been grouped according to the replies.

Table 2.

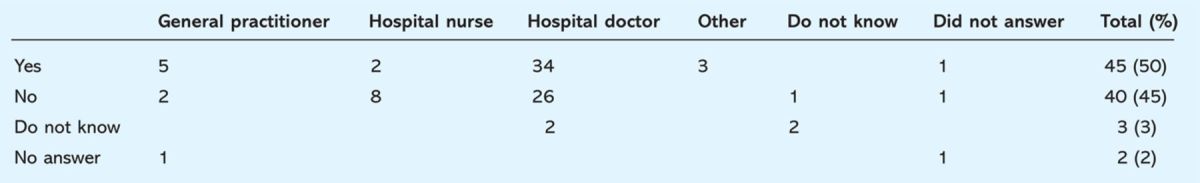

Response to the questions ‘Did you understand the meaning of the term “heart failure” at the time of diagnosis?’ and ‘Who gave you the diagnosis?’.

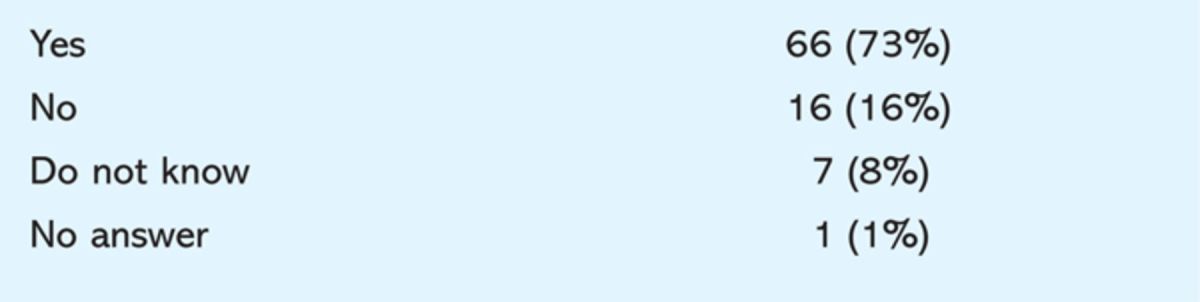

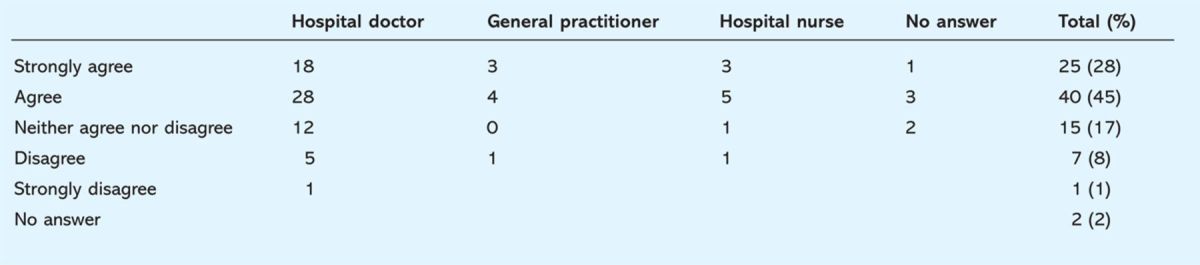

The majority (73%) of patients felt that they needed more information about heart failure, while only 16% said that they were satisfied with what they knew (Table 3). A hospital doctor informed the patient of the diagnosis in nearly 70% of the cases, while it was a HFN in 11%. General practitioners (GP) informed patients in 9% of cases. The remaining 10% could not remember who had given them the diagnosis (Table 2). Of the patients who were given the diagnosis by a hospital doctor and of those given the information by a GP, 62% and 54% respectively felt that they understood the diagnosis of heart failure as compared to 20% who were informed by a HFN (Table 2). There was no difference among the three groups when patients were asked whether the person who gave the diagnosis made them feel positive about the condition (Table 4). The majority of the patients seen by the HFN (80%) felt they were given some form of counselling as compared to 67% for the hospital doctors and 50% for the GPs (Table 5).

Table 3.

Did patients want more information about their condition beyond what was already offered?

Table 4.

How did the patient feel about the statement ‘The person who gave me the diagnosis of heart failure made me feel positive about living with this condition’.

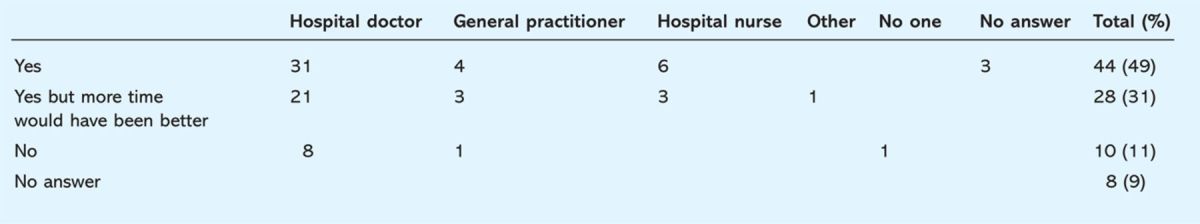

Table 5.

Were patients given any form of counselling? And if so, who by?

Table 6 shows that patients seen by the HFN were more likely to feel that they had enough time to discuss their diagnosis and were given time to ask questions as compared to the other two groups. However, only around one in 10 felt that there was insufficient time to discuss the diagnosis with the GP or hospital doctor. Similarly (Tables 7 and 8), the majority of patients in all three groups felt that they understood the answers given to their questions with a small proportion in the hospital doctors and GP groups feeling that they either did not understand or did not have time to ask questions.

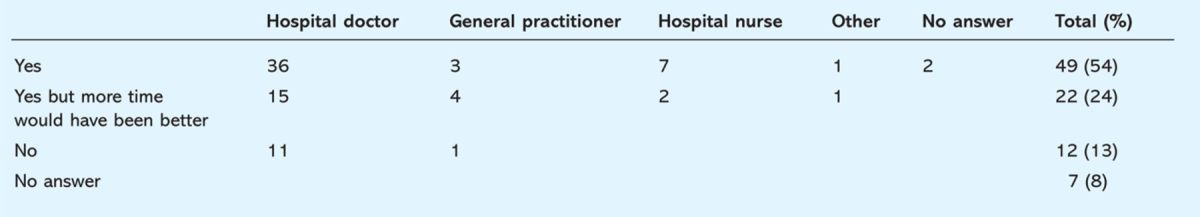

Table 6.

Did the patient feel that they had enough time to discuss the diagnosis and who was this discussion with?

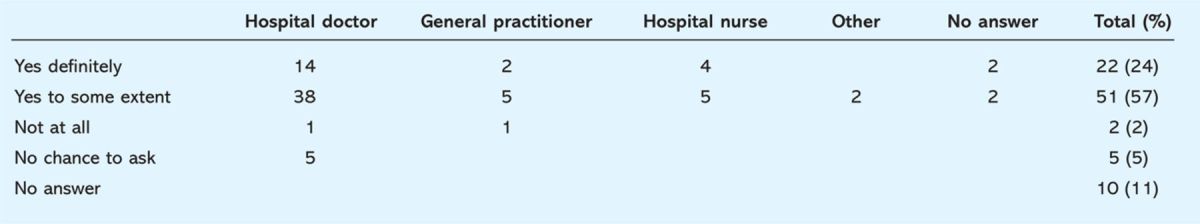

Table 7.

Did the patient understand the answers to questions they may have asked about their condition?

Table 8.

Were the patients given an opportunity to ask questions?

Discussion

This study shows that about half of the cohort studied felt that they understood the diagnosis of heart failure at the time of their first consultation. Of those 76% were given their diagnosis by a hospital doctor. Of the patients who did not understand their diagnosis, 66% were initially seen by a hospital doctor. These figures are slightly misleading and do not necessarily imply that doctors do not spend time in explaining the diagnosis, as the majority of patients (86%) were diagnosed either in hospital or in a hospital clinic, and the hospital doctor is the person most likely to inform of the initial diagnosis and to offer counselling. However, this does further stress the importance of physician and junior doctor training in patient counselling in general and those with heart failure in particular, as previous studies have demonstrated that junior doctors do not feel comfortable or competent in breaking bad news.6

Further analysis revealed that patients were less likely to understand the diagnosis if they were initially seen by a HFN than by a doctor (20% v 62%). Perhaps one of the reasons for this unexpected result is the fact that nursing staff are generally unlikely to make a diagnosis of heart failure on their own and would usually rely on doctors to inform the patient of the diagnosis in the first instance. Indeed in this study, HFNs informed the patient of the diagnosis in only 11% of cases.

This questionnaire also revealed that patients felt that they had more time to discuss and ask questions with the HFN than with a hospital doctor or their GP. Time is a very important factor in communication between a doctor and a patient. Occasionally patients feel that they do not want to waste the doctor's time in asking questions and leave the consultation room with inadequate information. The doctor on the other hand may feel that the GP or the HFN may be better suited to give more information and would refer them on without giving sufficient information. In addition, enough information regarding the poor prognosis may not be given due to a general reluctance to break bad news.7

When questioned as to whether the person who gave them the diagnosis made them feel positive about living with the condition 73% either agreed or strongly agreed that the diagnosis was imparted in a positive manner. It was the same whether the diagnosis was informed by either a nurse or a doctor. Avery suggests that if bad news is delivered poorly it may rob people of hope and start a chain of events that adversely affects the patient and family for years.8 From this study it would appear that the main bearers of bad news (hospital doctors) manage to impart the diagnosis and leave the patient with a positive outlook.

When the cohort was questioned as to whether they had been given any form of counselling with regards to their condition, 67% maintained that they had. However, given time constraints in the clinic setting, the heart failure team at UHCW NHS trust has adopted a policy of home visits by the nursing team to counsel and support patients following diagnosis. Despite this policy, 73% of the sample wanted more information on their condition although 63% felt they were given enough information on living with their heart failure.

It should be noted that for the purpose of this study the patient was not specifically questioned about prognostic information needs. However, the fact that a large proportion of patients did understand the seriousness of the diagnosis of heart failure and yet wished for more discussion of their diagnosis and more information on the condition may suggest that they also wish to learn more about their prognosis. A common theme emerging from the literature is that patients do want more information on their chronic conditions. Fine et al conducted a questionnaire-based study on patients with chronic renal failure to establish whether they wanted voluntary disclosure of survival rates should they need dialysis.9 Given that survival on dialysis is no different than with some forms of cancer, this was rarely broached in the consent process for treatment. A total of 100 patients completed the questionnaire with 46% expressing that they would like to know actual life expectancy on dialysis with 51% responding that they had an absolute need to know. The conclusion from this study was that virtually all patients want, and therefore should receive from their physician, prognostic information about dialysis to facilitate informed decision making.

How the bad news is delivered is of paramount importance, but morally one could question how ethical it is to ‘dumb down’ the seriousness of a diagnosis. Such a paternalistic view is in conflict with current thinking, centred round patient empowerment and choice.10

Time constraints are another important factor during counselling. The introduction of specialist heart failure clinics and the induction of specialist HFNs who can make home visits can, to a certain extent, overcome this constraint that is seen in hospital outpatient clinics.

Most of the patients in this study felt that they had some understanding of the disease process. Tayler et al conducted a study among primary care physicians about the terminology used when giving a diagnosis.11 If GPs described the condition in another way such as ‘fluid on the lungs’ it was not considered as serious as the term ‘heart failure’. The use of euphemisms was found to be protective to the patient. This would suggest that the way in which an illness is described impacts on the patient experience.

Conclusion

In general, the diagnosis of heart failure is often made in a hospital setting and a hospital doctor is usually the first person to impart this information to the patient. A substantial number of patients did understand the diagnosis and appreciated that it is a serious condition. They still, however, felt that they did not know enough and would like more information. This might suggest that patients would like more information on prognosis. The HFNs play an important part in the management of the condition in the community by being able to spend more time with the patients and help resolve any issues and impart more information as required. Patients also tend to feel more at ease with the specialist nurses especially when seen in the community. More training for doctors and HFNs in delivering the diagnosis of heart failure is recommended. Doctors delivering the diagnosis should also spend more time discussing it.

References

- 1.Mosterd A, Cost B, Hoes AW, et al. The prognosis of heart failure in the general population. The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 2001;22:318–27. 10.1053/euhj.2000.2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen LA, Yager JE, Funk MJ, et al. Discordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failure. JAMA 2008;299:2533–42. 10.1001/jama.299.21.2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomaselli GF, Zipes DP. What causes sudden death in heart failure?. Circ Res 2004;95:754–63. 10.1161/01.RES.0000145047.14691.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowie MR, Mosterd A, Wood DA, et al. The epidemiology of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1997;18:208–25. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stromberg A, Martensson J, Fridlund B, et al. Nurse-led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behavior in patients with heart failure. Results from a prospective, randomised trial. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1014–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggly S, Afonso N, Rogas G, et al. An assessment of residents' competence in the delivery of bad news to patients. Acad Med 1997;72:397–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radziewicz R, Baile W. Communication skills: breaking bad news in the clinical setting. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001;28:951–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avery J. Ethical issues in the management of geriatric cardiac patients. Am J Geriatric Cardiol 2002;11:413–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fine A, Fontaine B, Kraushar MM, Rich BR. Nephrologists should voluntarily divulge survival data to potential dialysis patients: a questionnaire study. Perit Dial Int 2005;25:269–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baile WF, Glober GA, Lenzi R, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. Discussing disease progression and end of life decisions. Oncology 1999;13:1021–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tayler M, Ogden J. Doctors' use of euphemisms and their impact on patients' beliefs about health: an experimental study of heart failure. Patient Educ Couns 2005;57:321–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]