Abstract

In the context of professionalism being viewed increasingly as a social contract, a survey was conducted to investigate the importance placed by the general public on doctors’ professional attributes. A quota sample of 953 responded to a 55-item online inventory of professional attributes. The quotas closely represented the national census. The majority of the highly important attributes focused on the relationship with patients. Statistically, the responses emerged as a three-facet model (clinicianship, workmanship and citizenship) of medical professionalism. The general public did not equate professionalism with social standing, wealth production, physique or appearance. They recognised doctors as professionals by their good behaviour, high values and positive attitudes as clinicians, workmen and citizens. Although, their preference of professional attributes varied with the setting, eg patient consultation, working with others and behaving in society, they expected doctors to be confident, reliable, dependable, composed, accountable and dedicated across all settings.

Key Words: medical professionalism, professional attributes, public view, social contract

Introduction

The concept of ‘medical professionalism’ probably emerged in the late medieval and early renaissance periods, when doctors organised a professional guild.1 However, it did not transform into the current definition until the late 20th century.2 In its earliest conceptualisation, professionalism was the practice standards and codes of conduct set by the practitioners themselves.1 Subsequently, at different historical stages, elements for guarding medical practice from other competing professions, and for controlling commercialisation of the profession, were included in the definition.1 Therefore, historically, ‘professionalism’ has been a moveable feast, responding to both political and societal changes.3,4

Even today, agreeing upon a common definition for healthcare professionalism has proved challenging.3 However, ‘there is a general agreement on the salient features of professionalism’ which include attitudes, values and behaviour.3 Until recently, medical professionalism was defined only through a doctor's perspective. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a shift towards a more public-centred view and, as a result, professionalism is increasingly recognised as a social contract between doctors and society.5–8 This relationship has been acknowledged by the regulatory authorities of the medical profession both within and outside the UK.9–14 With recent changes made to the UK healthcare workforce, eg the emergence of specialist nurses for performing minor surgery or endoscopy, the concept of professionalism may have to be widened to bring different healthcare professions under a single umbrella, ie poly-professionalism rather than uni-professionalism.15 The aim of this study was to investigate the importance placed by the general public on different professional attributes of doctors.

Methodology

The survey was conducted using a 55-item online inventory. Participants were asked to rate the importance of each item as a professional attribute for doctors on a five-point Likert scale (5 = extremely important and 1 = unimportant). Ethical approval was obtained from the research ethics committee of the University of Dundee.

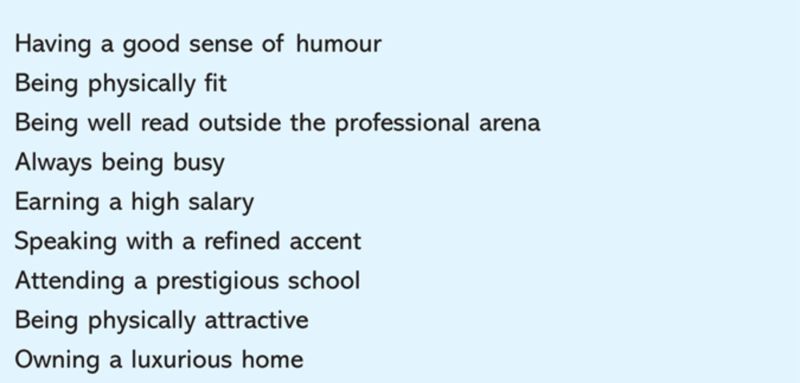

For the initial step of identifying the attributes of professionalism, documents published by the General Medical Council and the American Board of Internal Medicine were examined.9,10,12,16 As these tended to be guidelines rather than rules and there was no consensus on the attributes of healthcare professionalism, the list was supplemented with additional attributes identified by several researchers.17–37 The resultant 57 items were reviewed by 32 international medical educators. This group represented clinicians and basic scientists from the UK, USA, Asia, Africa and Australia involved in both or either undergraduate and postgraduate medical education. Based on their review, certain items were combined and others deleted and the list was condensed to 46. Another nine items, which are misconceptions related to professionalism and with no evidence base, were added to the list by the researchers (Box 1). The purpose of adding these items was to check for validity. Advice from professionals involved in public survey was sought to ensure the language of items used was appropriate to all social strata.

Box 1. Misconceptions included in the list of professional attributes.

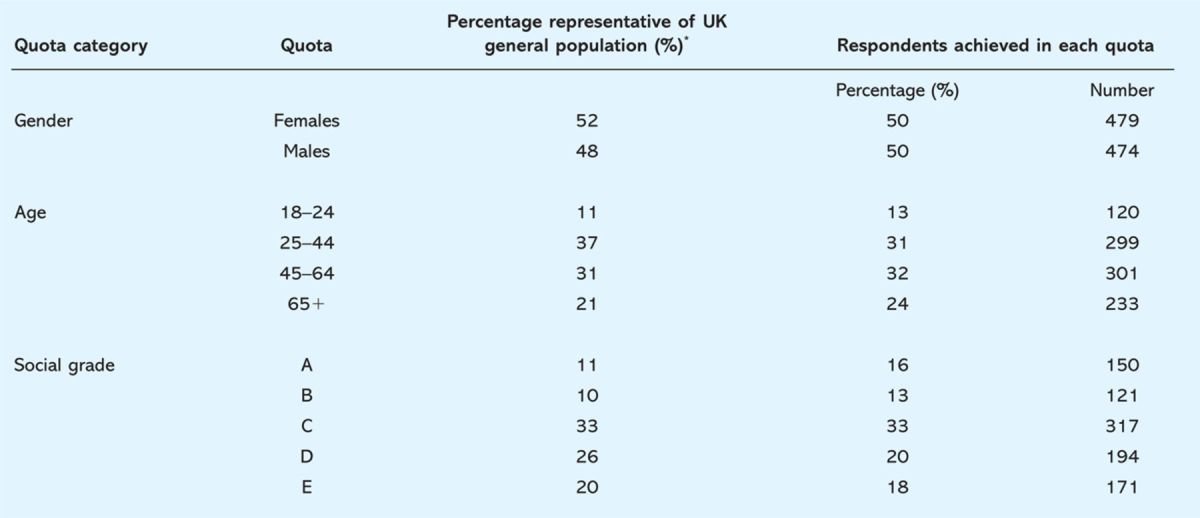

In this survey, a sample of the general public, representative of the main demographic characteristics, namely gender, age and social class, was used. Quota sampling, a technique which is the non-probability equivalent of stratified sampling was also adopted.38 A cohort of the general public, which had volunteered to take part in online surveys without payment, was accessed through a private marketing firm. The target was to achieve quotas representative of the national census with approximately 800 respondents. Satisfactory numbers for all quotas were finally achieved with 953 respondents.

The possible limitations of this study may be the use of a quota sample rather than a random sample and the delivery of the survey online. The validity of findings for the research question, however, was best achieved with a representative sample rather than a random sample. With 65% of the UK population currently having access to the internet, with impressive coverage across different age, gender and social groups,39 the argument for online delivery being a possible cause for bias has very little value. Therefore, the possible biases are outweighed by the accessibility of a predefined national stratified sample through this relatively novel approach.

Results

The percentage representation of each demographic quota closely matched by the national statistics (Table 1). In addition, there was adequate representation of the general public from different geographical areas in the UK.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of the study population and representativeness of demographic quotas.

The internal consistency of the 55-item inventory was very high (Cronbach's alpha = 0.95) which suggests that the items including those nine added by the researchers were focused on the same construct (ie professionalism).

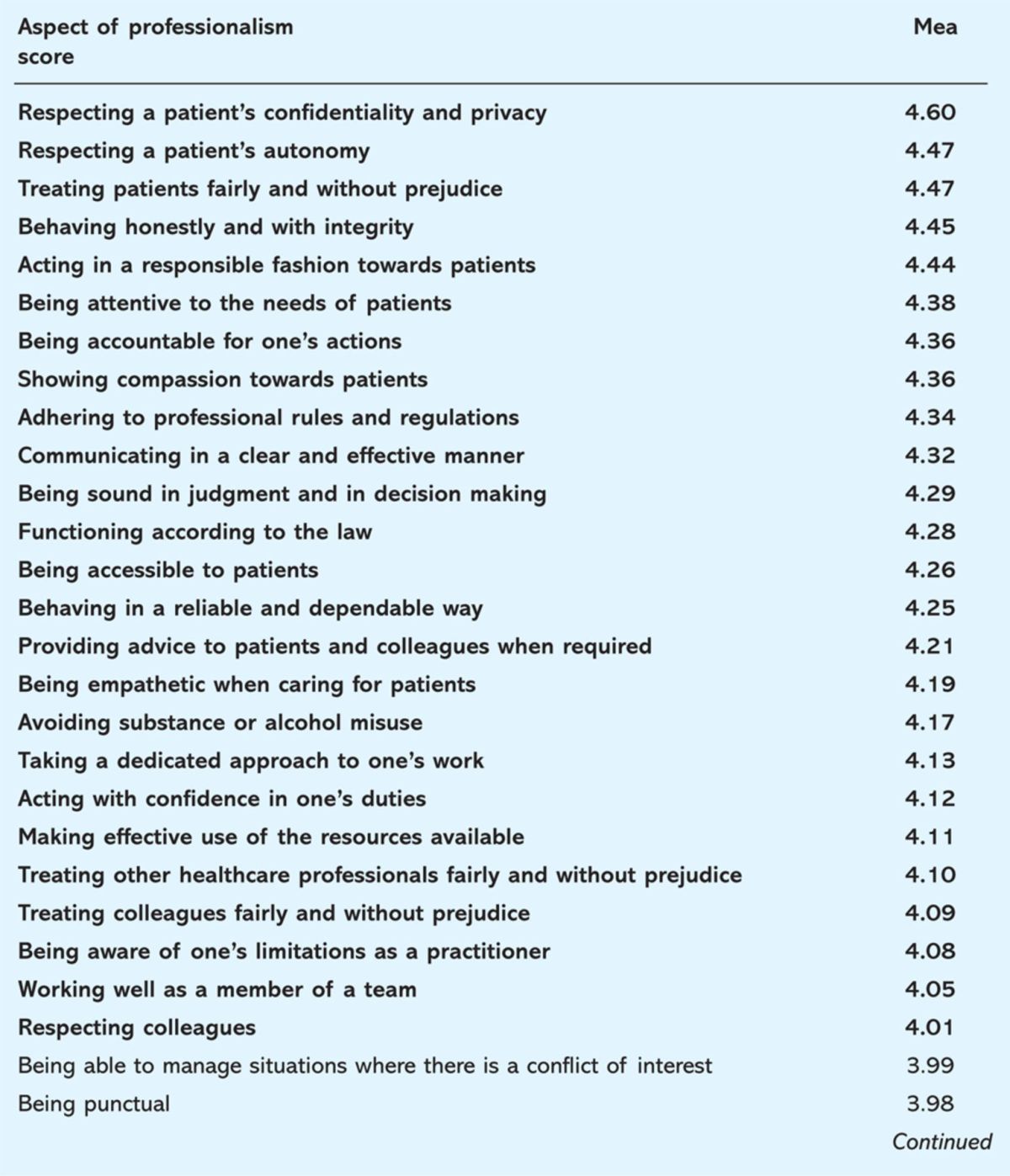

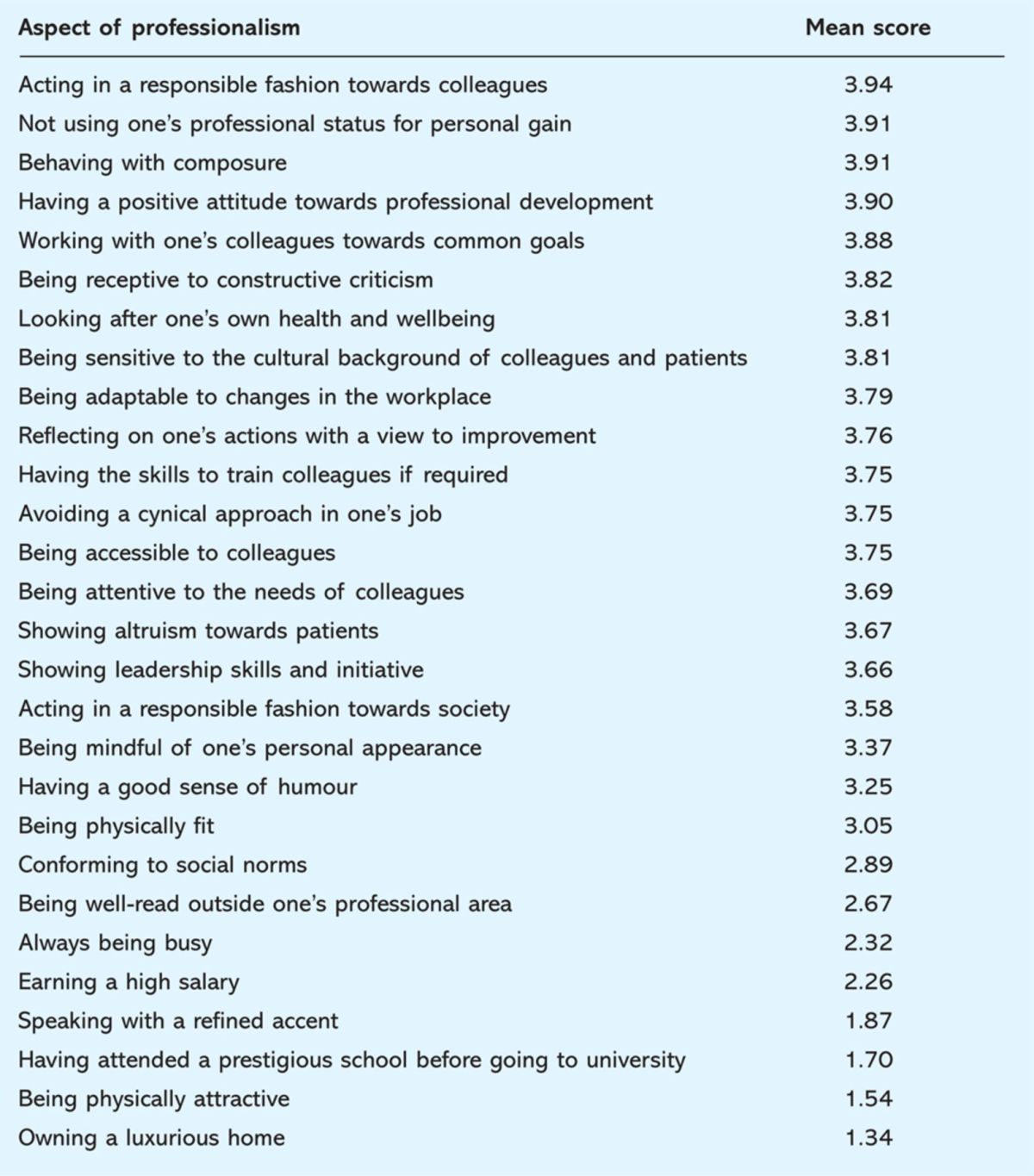

The respondents felt that all attributes of professionalism identified by the organisations were ‘extremely’ or ‘somewhat’ important. However, attributes related to personal appearance, eg dress code,25,36 and conforming to social norms,32,37 which were identified in earlier studies, were categorised as ‘slightly important’ or ‘unimportant’. All nine items included by the researchers, which were thought to be social misconceptions on professionalism, were rated among the bottom 10 items. The mean rating for each item is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean score given to different attributes of professionalism by the general public (n=953). The items in bold were rated as extremely to very important.

When ranked according to mean score, 25 of the attributes were categorised as ‘extremely important’ or ‘very important’ by the general public. Many were related to the relationship with patients, eg respecting a patient's confidentiality and privacy and showing compassion towards patients, and personal qualities, eg functioning according to the law and avoiding substance or alcohol misuse. Some of them were related to the relationship towards co-workers, eg treating colleagues and other healthcare professionals fairly without prejudice and working well as a member of a team.

There were significant gender differences in the rating of 22 of the top 25 items. The majority of these items fell within the ‘extremely important’ or ‘very important’ bracket, ie five and four of the rating scale. The statistical differences, therefore, may not have significant practical implications. Age did not seem to be a factor in the rating of items with only six out of the top 25 showing any statistical significance, nor did social status have any impact on the ratings.

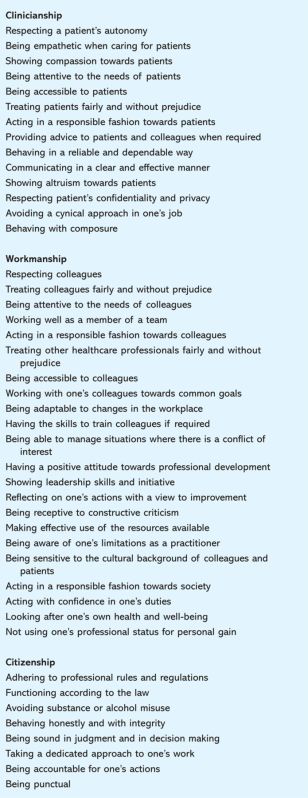

Factor analysis of the 55 items identified three meaningful principle components: interaction with patients, interaction with co-workers and the work place, and interaction with society (Box 2). The planned misconceptions on professionalism, added by the researchers, together with the item ‘conforming to social norms’ formed a fourth component.

Box 2. Attributes grouped together in the factor analysis.

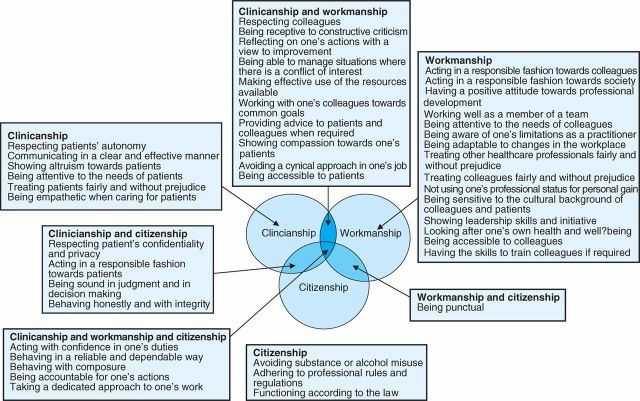

In the principle component analysis, certain items demonstrated acceptable correlations (>0.3) with a second or a third component. This was helpful in making a meaningful relationship between the three components (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Professional attributes which share different facets of medical professionalism.

Discussion

Three facets of professionalism, which the general public would like to be exhibited by their doctors, were identified. Unsurprisingly, as a doctor's main role is the treatment of patients, items relating to patient care were given a high priority. However, certain attributes towards co-workers and society also featured highly. The general public expect doctors to be professional as a clinician, ie when interacting with patients, as a worker, ie when working with colleagues and other professionals, and as a citizen, ie a moral and law-abiding individual. However, the relationship of these facets was not mutually exclusive. For example, respecting colleagues or reflective practice are attributes which are contributory to both workmanship and clinicianship. Therefore, the three facets may be more appropriately described as three overlapping circles (Fig 1). The three-facet framework may be a further step towards recognising a doctor's professional behaviour in terms of being a healer and a professional3 or recognising their commitment to the values of an individual and in their relationship with patients. On the other hand, the general public does not equate professionalism with social standing, wealth production or physique. These low and high ratings were virtually constant across gender, age and social classes. The majority of elements identified under primary and secondary themes of professionalism by Wagner et al can be categorised under the three facets identified in this study.40 However, sense of humour, dress code and appearance featured prominently in Wagner et al's study unlike in these results.40 A paper by van-de-Camp et al suggested that three themes come under the definition of professionalism namely inter-, intra- and public professionalism.41 These themes are a sound framework for conceptualising professionalism. However, the items categorised under each theme were not in concordance with the component analysis findings of the current survey. Almost all items found by van-de-Camp et al were perceived by the public as important in the current study.41

In conclusion, in the context of professionalism being viewed increasingly as a social contract, the general public recognises doctors as professionals by their good behaviour, high values and positive attitudes related to clinicianship, workmanship and citizenship. They would like to see certain attributes of this contract demonstrated in various settings, eg during patient consultation, working with colleagues and other professionals or behaving in society. However, they expect doctors to be confident, reliable, dependable, composed, accountable and dedicated across all settings. Personal appearance, physical features or social standing may play little or no role in a doctor being considered ‘professional’.

Acknowledgements

Centre for Medical Education, University of Dundee, for providing funds for the project and Survey Sampling UK Ltd for providing professional advice and access to the study population.

Funding

Internal funds of the Centre for Medical Education, University of Dundee, UK were used to pay Survey Sampling UK Ltd, which assisted in the development and dissemination of the online survey.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this project was obtained from the University Research Ethics Committee of the University of Dundee.

References

- 1.Sox CH. The ethical foundations of professionalism; a sociologic history. Chest 2007;131:1532–40. 10.1378/chest.07-0464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold EL. Assessing professional behaviour: yesterday, today and tomorrow. Acad Med 2002;77:502–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruess SR, Cruess RL. The cognitive base of professionalism In Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y, Teaching medical professionalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009 10.1017/CBO9780511547348.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wass V. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Clin Med 2006;6:109–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold L, Stern DT. What is medical professionalism? In: Stern DT, Measuring medical professionalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0162.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martimianakis MA, Maniate JM, Hodges BD. Sociological interpretations of professionalism. Med Educ 2009;43:829–37. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism: a contract between medicine and society. JAMC 2000;162:668–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Expectations and obligations: professionalism and medicine's social contract with society. Perspect Biol Med 2008;51:579–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.General Medical Council Tomorrow's doctors. London: GMC, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.General Medical Council Good Medical Practice. London: GMC, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen R, Dewar S. On being a doctor: redefining medical professionalism for better patient care. London: King's Fund, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stobo JD. Project professionalism: staying ahead of the wave. Project professionalism. Philadelphia: American Board of Internal Medicine, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Medical Association CMA code of ethics. Ottawa: CMA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medical Professionalism Project Medical professionalism in the next millennium: a physician charter. Annals Intern Med 2002;136:243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roff S, McAleer S, Chandratilake M, Dherwani K, Gibson J. Developing stage-specific, consistent, reliable and valid learning, teaching and assessment methods for PolyProfessionalism in the health professions. Issues and News on Learning and Teaching in Medicine, Dentistry and Veterinary Medicine 2009;1:18–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.General Medical Council Medical students: professional values and fitness to practise. London: GMC, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett AJ, Roman B, Arnold LM, Kay J, Goldenhar LM. Professionalism deficits among medical students: models of identification and intervention. Acad Psychiatry 2005;29:426–32. 10.1176/appi.ap.29.5.426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson RE, Obhenshain SS. Cheating by students: findings, reflections and remedies. Acad Med 1994;69:323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Testerman JK, Morton KR, Loo LK, et al. The natural history of cynicism in physicians. Acad Med 1996;71(Suppl 1):S43–45. 10.1097/00001888-199610000-00040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Culhane-Pera K, Reif C, Egli E, et al. A curriculum for multicultural education in family medicine. Fam Med 1997;29:219–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sulmasy DP, Dwyer M, Marx E. Knowledge, confidence and attitudes regarding medical ethics: how do faculty and housestaff compare. Acad Med 1995;70:1038–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SR, Balint JA, Krause KC, Moore-West M, Viles PH. Performance-based assessment of moral reasoning and ethical judgement among medical students. Acad Med 1994;69:381–6. 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phelan S, Obenshain SS, Galey WR. Evaluation of the noncognitive professional traits of medical students. Acad Med 1993;68:799–803. 10.1097/00001888-199310000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waz WR, Henkind J. The adequacy of medical ethics education in a paediatric training programme. Acad Med 1995;70:1041–3. 10.1097/00001888-199511000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruess RL, McIlroy JH, Ginsburg S, Steinert Y. The professionalism mini-evaluation exercise: a preliminary investigation. Acad Med 2006;81:74–8. 10.1097/00001888-200610001-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risdon C, Baptiste S. Evaluating pre-clinical professionalism in longitudinal small group. Med Educ 2006;40:1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van-de-Camp K, Vernooij-Dassesn M, Grol R, Bottema BJAM. Professionalism in general practice: development of an instrument to assess professional behaviour in general practice. Med Educ 2006;40:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalet AL, Steven H. Measuring professionalism attitudes and beliefs. 27th Annual Meeting of the Illinois Society of General Internal Medicine. Chicago: Illinois Society of General Internal Medicine, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musick DW, McDowell SM, Clark N, Salcido R. Pilot study of a 360 degree assessment instrument for physical medicine and rehabilitation programmes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2003;82:394–402. 10.1097/01.PHM.0000064737.97937.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hebert PC, Meslin EM, Dunn EV. Measuring the ethical sensitivity of medical students: a study at the University of Toronto. J Med Ethics 1992;1992:142–7. 10.1136/jme.18.3.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stark P, Roberts C, Newble D, Bax N. Discovering professionalism through guided reflection. Med Teach 2006;28:e25–31. 10.1080/01421590600568520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swick HM. Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Acad Med 2000;75:612–6. 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhoton MF. Professionalism and clinical excellence among anaesthesiology residents. Acad Med 1994;69:313–5. 10.1097/00001888-199404000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papadakis MA, Osborn EHS, Cooke M, Healy K. A strategy for the detection and evaluation of unprofessional behaviour in medical students. Acad Med 1999;74:980–90. 10.1097/00001888-199909000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papadakis AM, Loeser H, Healy K. Early detection of evaluation of professionalism deficiencies in medical students: one school's approach. Acad Med 2001;76:1100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Luijk SJ, Smeets JGE, Smits J, Wolfhangen I, Perquin MLF. Assessing professional behaviour and the role of academic advice at the Maastricht medical school. Med Teach 2000;22:168–72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holtman MC. A theoritical sketch of medical professionalism as a normative complex. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2008;13:233–45. 10.1007/s10459-008-9099-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen L, Manion L. Research methods in education. New York: Routledge, 1994 10.4324/9780203224342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Office for National Statistics . Internet access 2008: households and individuals. www.statistics.gov.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner P, Hendrich J, Moseley G, Hudson V. Defining medical professionalism. Med Educ 2007;41:288–94. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van-de-Camp K, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Grol RPTM, Bottema BJAM. How to conceptualise professionalism: a qualitative study. Med Teach 2004;26:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]