In urban areas of the UK up to 50% of the population may come from a non-white British ethnic background.1 Ethnic factors, such as beliefs and cultural context, compounded by language and social factors, affect access to, and quality and outcome of, healthcare, in particular with regards to chronic diseases. A number of rheumatic conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and osteomalacia, show particular prevalence and/or disease expression according to ethnic factors. In common with many other medical specialties, it remains poorly understood how ethnic factors impact on healthcare provision in rheumatic diseases. More research is required before equity of healthcare across the ethnic spectrum can become a reality.

Many chronic diseases, such as musculoskeletal disorders, diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart and chronic airway disease, are more prevalent in black and Asian ethnic individuals and can be associated with higher mortality.2 Chronic disease requires long-term management and central to this is active patient participation.3 This depends on their willingness and motivation to accept diagnosis and treatment, and to actively seek ways to cope with the disease. Involving patients from an ethnic background in this process remains a challenge, particularly among the South Asian population in the West Midlands.4,5 It is widely known that patients from different ethnic backgrounds have diverse views about disease, its causation and treatment and these are influenced by many factors including cultural or communication barriers.6–9 Potentially, these views and barriers may have a detrimental effect on disease outcomes.

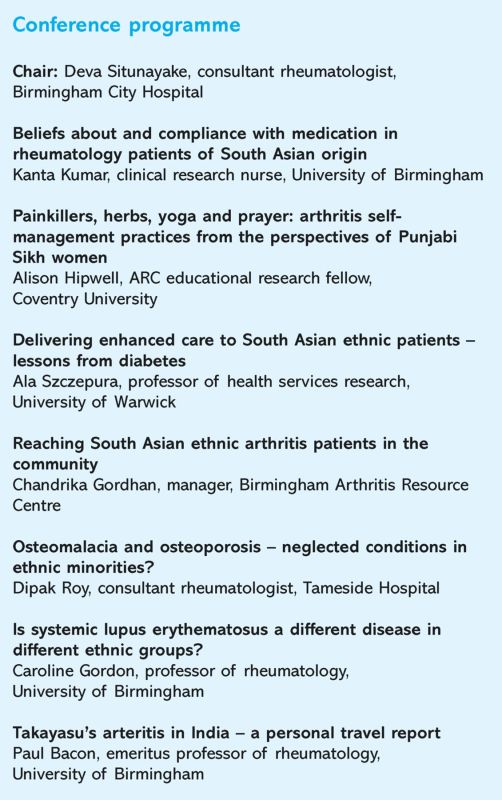

The 2009 West Midlands Rheumatology Forum, a multidisciplinary forum of health professionals allied to rheumatology, brought together research evidence and experience of health professionals with an interest in this area. The discussions covered a wide range of issues associated with ethnicity and its potential impact on the delivery of care. There was a clear convergence of opinion that far more research is required to understand how ethnic factors influence rheumatic disease, patient involvement and access to healthcare.

Deva Situnayake, who chaired the meeting, set the scene by introducing the concept underpinning the chronic care model. He highlighted requirements that are fundamental to change patients outcomes: an informed patient participating actively in partnership with engaged clinicians and the extended multidisciplinary team. This requires effective system design of healthcare delivery, increasingly linked to the community and with improved IT support. For patients to be at the centre of every decision made about their care, they need the relevant knowledge and facts. Some patients of South Asian ethnic origin may lack this capacity in decision making mainly because they may have different views about disease or have the added communication challenge. This point was illustrated by Kanta Kumar who presented her research on patients’ beliefs about medicines in white British and South Asian patients. Her findings shed light on South Asian patients’ reasons for negative beliefs mainly related to a patient's lack of understanding of a disease, influenced by cultural background and communication barriers hindering involvement in disease management. These negative beliefs may lead patients to abandon their prescribed pharmacological treatment. Her talk outlined the need to provide patients with a better understanding of the disease and treatments. She presented solutions that may help to tackle the problem, for example providing an Asian language telephone helpline supported by bilingual staff, providing the opportunity to talk to fellow patients in their own language and supplementing this with a bilingual audio CD on specific rheumatic diseases. She concluded that understanding a patient's knowledge and beliefs is vital in order to create innovative new pathways of communication.

Alison Hipwell presented her research on the development of an arthritis self-management programme for Punjabi Sikh women with osteoarthritis. This work was triggered by the observation that from a community with 48% of South Asian ethnic background, not a single South Asian ethnic patient had attended an expert patient programme. Hipwell found that, rather than being passive recipients of healthcare, Punjabi Sikh women already use a wide range of strategies to self-manage their disease. These strategies were rooted strongly in traditional culture and in particular religious beliefs. She showed that an arthritis self-management programme tailored around these existing beliefs and coping mechanisms was well received by women from this community. Such findings are important in shaping future service provision.

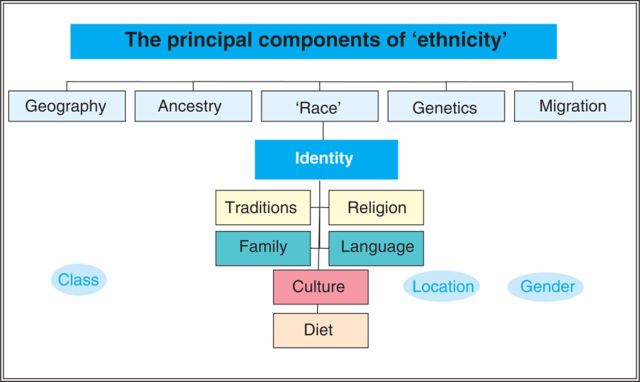

Ala Szczepura reminded the audience that all NHS staff and institutions have a legal requirement to address race-related inequalities in healthcare provision (Race Relations Amendment Act 2000). Presently, there is insufficient information on evidence-based medicine, service provision and usage for many ethnic minority groups and chronic conditions including most rheumatic diseases are no exception. She explained the difficulties in defining the term ethnicity (Fig 1) and contrasted this with the term race, which contains less determining factors. Before race equality can improve in practice – and provision can mean equity of care – much better collection of data is required. She introduced NHS initiatives, such as the Race for Health that strives to improve race equality in healthcare delivery. She also encouraged the rheumatology healthcare community to submit examples of best practice via the NHS evidence website (www.library.nhs.uk/ethnicity).

Fig 1.

The complex aspects of ethnicity. Courtesy of Professor Szczepura, University of Warwick

Chandrika Gordhan described how the Birmingham Arthritis Research Centre (BARC), situated in Birmingham Central Library, has been tackling some of these problems in South Asian patients based on a published needs assessment process. In addition to a support service for both patients and carers, trained patient volunteers offer a range of disease information in local languages in bi-lingual written or audio format. These have been shown to enhance coping skills for patients with musculoskeletal disease. BARC runs in parallel with the standard NHS service, with the ability to save time for busy doctors as well as help patients.

Dipak Roy presented data that highlighted the problem of osteomalacia and osteoporosis among South Asian women. Such women have significantly lower bone mineral density (BMD) as compared with women of European Caucasian origin. Smaller body size and low vitamin D are major contributing factors for these observed differences. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent among South Asian women which is thought to be due to a variety of factors including a darker skin pigment, compounded by dress code and reduced sun exposure, diet and possibly altered vitamin D metabolism. He reminded the audience that low BMD measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry scan cannot distinguish between osteoporosis and osteomalacia, that a normal bone profile does not exclude metabolic bone disease and that both 25-hydroxi-vitamin D and parathyroid hormone need to be measured to identify vitamin D deficiency accurately. Before treatment with bisphosphonates for low BMD, it is important to ensure that the patient is vitamin D replete. He recommended supplementation with ergocalciferol/cholecalciferol, which may be given as a single high dose oral bolus (150,000 to 300,000 iu), followed by maintenance therapy with calcium-vitamin D in the long term. He concluded that further research about fragility fracture incidence and treatment strategies are required in this population.

Conference programme.

Caroline Gordon gave a comprehensive talk on the impact of ethnicity on SLE. Afro-Caribbean and South Asian ethnic groups have a higher incidence and prevalence of this disease (5 and 2.5 times, respectively) compared with white Caucasians, irrespective of their country of birth. Disease expression also follows an ethnic-racial pattern: non-Caucasian patients are more likely to have renal involvement and serositis and generally more severe disease activity, but are less likely to suffer with photosensitive rashes compared with Caucasian patients. It is thought that both increased prevalence and diverse disease manifestation have a significant genetic basis, but this area needs a lot more research. While SLE patients from Black and Asian ethnic backgrounds have increased mortality, it remains to be determined how much of this is due to lower social/educational status rather than factors relating to ethnicity.

Paul Bacon reported his experience of Takayasu's arteritis, a rare form of large vessel vasculitis, in India based on personal exchange visits between academic units in Birmingham and the subcontinent. This aorto-arteritis appears more common in India than in the western world and therefore more robust epidemiological data about the disease and its presentation have been gathered in Indian patient cohorts. The most common clinical presentation is with an acute ischaemic event such as a stroke, while pulse inequality is the most common physical sign. Polymyalgic symptoms such as fever, headaches and arthralgias were not identified before the acute event. Bacon also presented data on the successful development of clinical assessment tools to quantify disease damage and activity for this condition. He showed impressive data about exemplary outcome rates for over 150 patients with Takayasu's arteritis from a single centre in Vellore following angioplasty of carotid, coronary and renal arteries, an intervention widely used in India although often regarded as high risk in other parts of the world. Conversely, he showed how Wegener's granulomatosis, as a small vessel vasculitis, became increasingly recognised in a north Indian rheumatology centre, following an educational visit of the lead rheumatologist to the unit in Birmingham.

Funding

This meeting was supported by an unrestricted educational grant by Wyeth and Pfizer.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Chandrika Gordan, Alison Hipwell, Dipak Roy, Deva Situnayake and Paul Bacon who reviewed their relevant section of this manuscript. The West Midlands Rheumatology Forum is a multi-professional group of medical and allied health professional working in rheumatology in the West Midlands. For further information or to be included on the mailing list about future meetings, please contact Rainer.Klocke@dgoh.nhs.uk

References

- 1.Office of National Statistics Census data 2001. London: ONS, 2001. www.statistics.gov.uk?census2001/profiles/commentaries/ethnicity.asp [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhopal R, Hayes L, White M, et al. Ethnic and socio-economic inequalities in coronary heart disease, diabetes and risk factors in Europeans and South Asians. J Public Health Med 2002;24:95–105. 10.1093/pubmed/24.2.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorig K, Visser A. Arthritis patient education standards: a model for the future. Patient Educ Couns 1994;24:3–7. 10.1016/0738-3991(94)90023-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhopal RS, Donaldson LJ. Health education for ethnic minorities – current provision and future directions. Health Educ J 1988;47:137–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhopal RS. The public health agenda and minority ethnic health: a reflection on priorities. J R Soc Med 2006;99:58–61. 10.1258/jrsm.99.2.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar K, Gordon C, Toescu V, et al. Beliefs about medicines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison between patients of South Asian and White British origin. Rheumatology 2008;47:690–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar K, Gordon C, Barry R, et al. ‘It's like taking poison to kill poison but I have to get better': A qualitative study of beliefs about medicines in RA and SLE patients of South Asian origin. Rheumatology 2009;48:i160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lip GY, Khan H, Bhatnagar A, et al. Ethnic differences in patient perceptions of heart failure and treatment: the West Birmingham heart failure project. Heart 2004;90:1016–9. 10.1136/hrt.2003.025742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenhalgh T, Helman C, Chowdhury AM. Health beliefs and folk models of diabetes in British Bangladeshis: a qualitative study. BMJ 1998;316:978–83. 10.1136/bmj.316.7136.978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]