Abstract

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) or temporal arteritis (TA) with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is among the most common reasons for long-term steroid prescription. GCA is a critically ischaemic disease, the most common form of vasculitis and should be treated as a medical emergency. Visual loss occurs in up to a fifth of patients, which may be preventable by prompt recognition and treatment. The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) and the British Health Professionals in Rheumatology (BHPR) have recently published guidelines on the management of PMR. The purpose of this concise guidance is to draw attention to the full guidelines to encourage the prompt diagnosis and urgent management of GCA, with emphasis on the prevention of visual loss. They provide a framework for disease assessment, immediate treatment and referral to specialist care for management and monitoring of disease activity, complications and relapse.

Key Words: diagnosis, giant cell arteritis, steroid therapy, treatment

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is the most common of all the vasculitides. Together with polymyalgia rheumatic, it represents one of the most common indications for long-term glucocorticosteroid therapy in the community. It is characterised by critical ischaemia at presentation and ranks among the common causes of acute blindness. Visual loss occurs in up to one-fifth of patients and this may relate to late recognition. Early recognition, referral and treatment are essential and GCA should be regarded as a medical emergency. However, it is subject to wide variations in clinical practice, as it is often managed in primary or in secondary care by general practitioners, rheumatologists, non-rheumatologists and ophthalmologists.

Aims of the guideline

The objective of this concise guidance is to produce a summary of the longer guidelines,1 and to improve the consistency of clinical practice by providing recommendations in the following areas:

a prompt diagnostic, management and referral process for GCA

appropriate advice on management of GCA with emphasis on prevention of vision loss with early recognition and prompt high-dose glucocorticosteroid therapy

investigations (such as temporal artery biopsy) for disease diagnosis and assessment of severity, using clinical factors and histology

appropriate advice on disease monitoring and treatment of relapses

appropriate advice on bone protection and prevention of steroid side effects.

Information in this concise guidance has been extracted from the full guideline. Please refer to the full guidance for details of the methodology. The guidelines were developed using the AGREE format and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guidance was used to grade the recommendations.

Early diagnosis

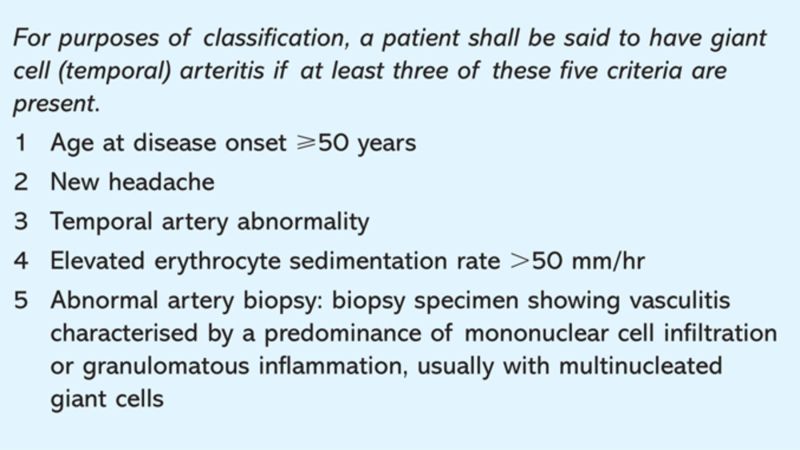

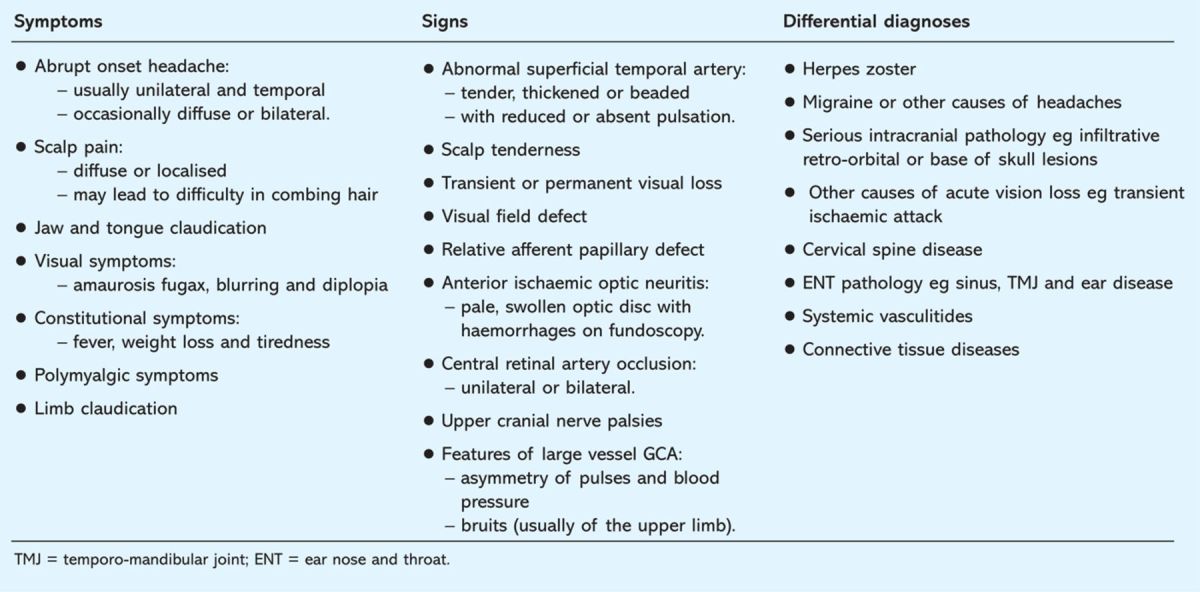

Early recognition and diagnosis of GCA is paramount. Common symptoms and signs are shown in Table 1, and criteria for diagnosis are shown in Box 1.2 Clinicians should remember that jaw and tongue claudication, visual symptoms, constitutional symptoms and acute phase response may go unrecognised especially if not accompanied by headaches.3 Patients at highest risk of neuro-ophthalmic complications do not always mount high inflammatory responses.

Table 1.

Common symptoms and signs of giant cell arteritis (GCA)

Box 1. The American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for giant cell arteritis.2.

Temporal artery biopsy (TAB) is the cornerstone of diagnosis and often remains positive for two to six weeks after the commencement of treatment. A regular link with a local dedicated surgical unit experienced in TAB to support urgent referrals is recommended. However, TAB may be negative in some patients with GCA, due to the presence of skip lesions or to sub-optimal biopsy. Therefore, patients with negative biopsies should be managed as having GCA if there is a typical clinical and laboratory picture and response to steroids, typical findings on ultrasound, or neuro-ophthalmic features typical of GCA (eg anterior ischaemic optic neuritis).

Duplex ultrasonography can detect the characteristic appearance of a hypoechoic ‘halo’, occlusions and stenosis, but requires a high level of experience and training. Positron emission tomography scanning can pick up aortic and large vessel disease; and 3-tesla magnetic resonance imaging has shown mural enhancement in inflamed temporal and occipital arteries. These techniques show promise for the diagnosis and monitoring of GCA (particularly large vessel disease), but currently do not replace TAB for cranial GCA.

Treatment and complications of GCA

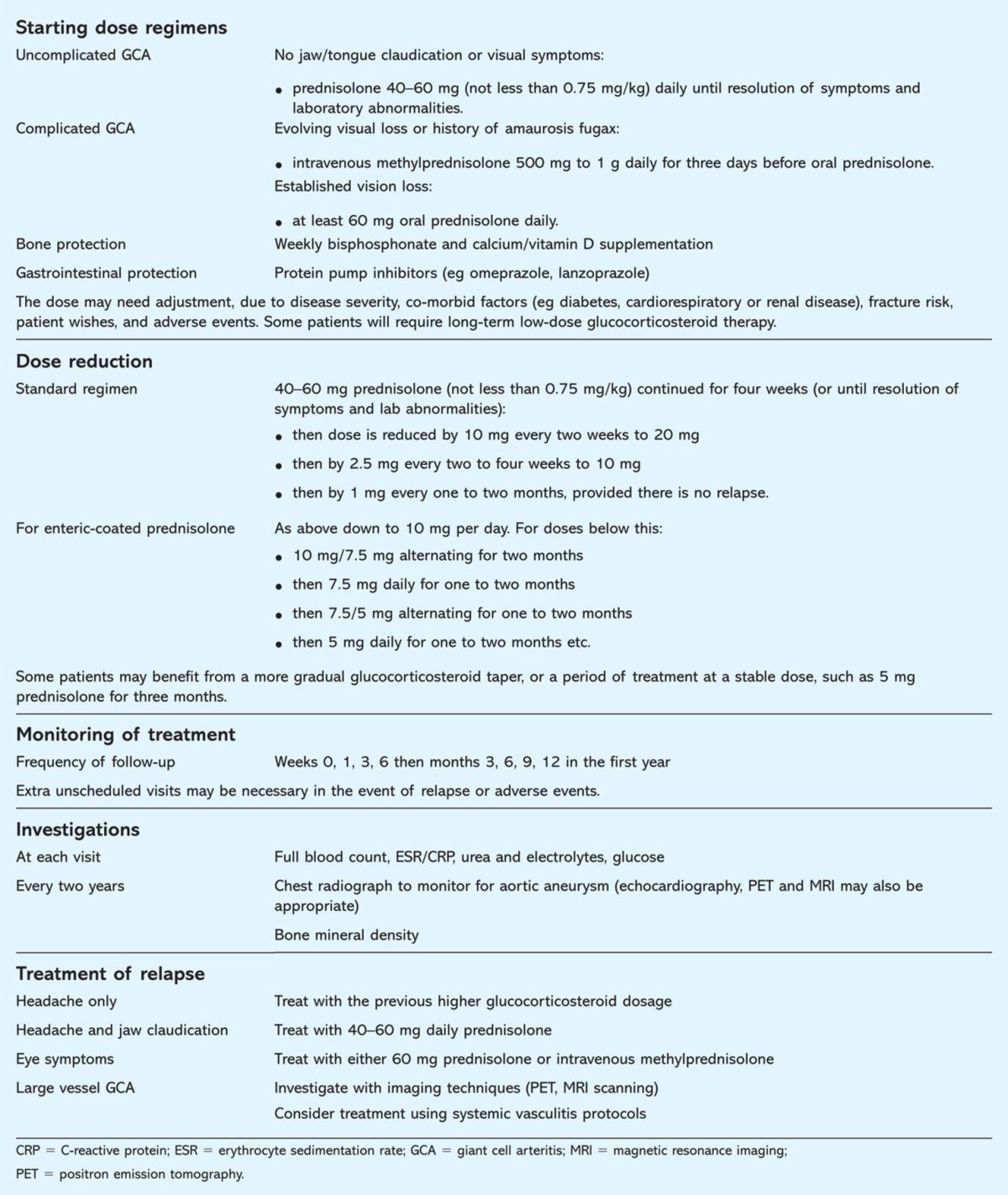

Prompt treatment with high-dose steroids is critical to reduce the likelihood of neuro-ophthalmic complications. The early complications are ischaemic deficits, such as vision loss and stroke. If one eye is affected there is high risk (20–50%) of bilateral vision loss with further delay or stoppage of treatment. Late complications include the development of aortic aneurysms.

The symptoms of GCA should respond rapidly to high-dose glucocorticosteroid treatment, followed by resolution of the inflammatory response. Failure to do so should raise the question of an alternative diagnosis. Steroid-related complications (eg weight gain, fractures, diabetes, hypertension, cataracts and bruising) are also common hence the importance of monitoring and titrating the dose down as soon as it is safe to do so. Low-dose aspirin has also been shown to decrease the rate of visual loss and cerebrovascular accidents in GCA.4 In recurrent or resistant GCA, methotrexate or other immunosuppressives (eg azathioprine or leflunomide) may be used as adjuvant therapy to allow reduction in the cumulative glucocorticosteroid dose, or a higher probability of glucocorticosteroid discontinuation without relapse.5

Implications and implementation

There are no cost implications for implementation of these guidelines apart from relevant training for general practitioners who should also have access to the routine investigations outlined and the ability to follow up as suggested. A referral pathway for GCA compatible with these guidelines is suggested in the Map of Medicine.

Further information on the guidelines, ie references, guideline development process, implications and implementation, is available at Rheumatology online with the full guidelines.1,6 An Arthritis Research Campaign booklet on GCA incorporating the guidelines will be published shortly. The booklet has being developed with recommendations from various patient representatives and members of patient organisations such as the Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis UK.

Table 2.

Recommended regimens for glucocorticosteroid treatment.

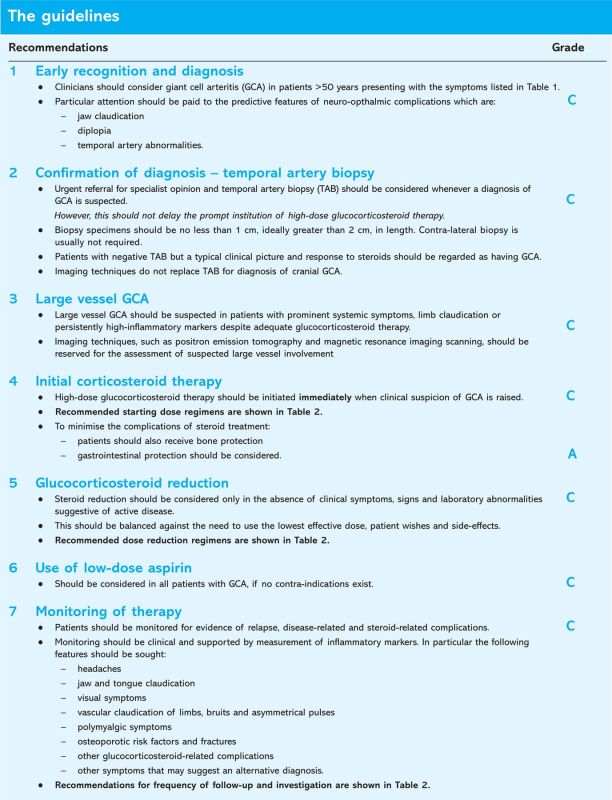

The guidelines.

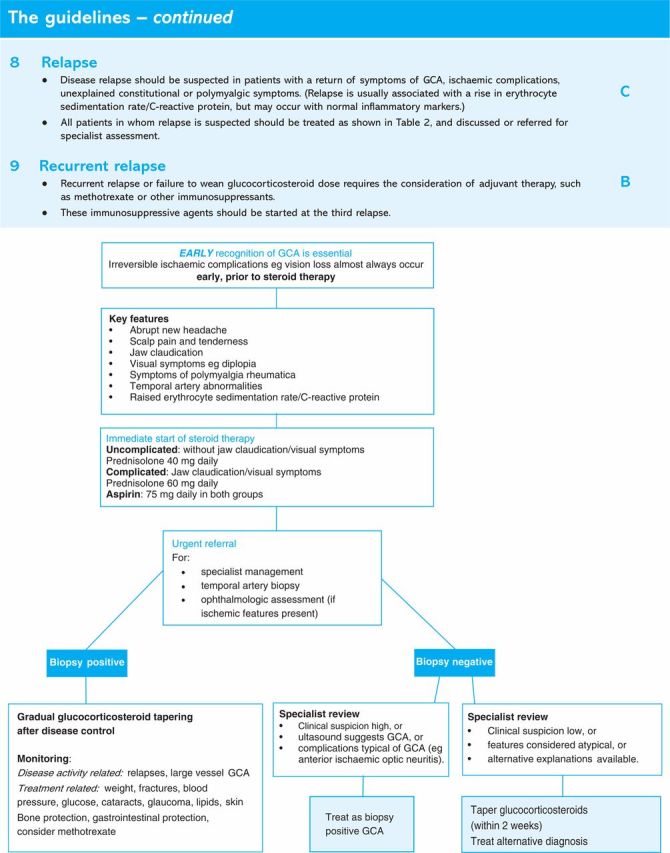

Fig 1.

Pathway for management of giant cell arteritis (GCA).

References

- 1.Dasgupta B, Borg FA, Hassan N, et al. BSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010 Apr 5 (epub ahead of print). 10.1093/rheumatology/keq039a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1122–8. 10.1002/art.1780330810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borg FA, Salter VLJ, Dasgupta B. Neuro-ophthalmic complications in giant cell arteritis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2008;8:323. 10.1007/s11882-008-0052-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nesher G, Berkun Y, Mates M, et al. Low-dose aspirin and prevention of cranial ischemic complications in giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1332–7. 10.1002/art.20171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahr AD, Jover JA, Spiera RF, et al. Adjunctive methotrexate for treatment of giant cell arteritis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2789–97. 10.1002/art.22754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Physicians Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: guidelines for prevention and treatment. London: RCP, 2002. [Google Scholar]