Abstract

The primary antibody deficiency syndromes are a rare group of immunodeficiencies where diagnostic delay remains common due to limited awareness of the existence and heterogeneity of their presenting features. Referral for specialist assessment leads to earlier diagnosis and appropriate therapy to prevent or limit structural organ and tissue damage. Greater education of healthcare professionals is required to ensure prompt recognition and referral to specialists with expertise in the care of primary immunodeficiencies, especially since study of these rare conditions is a minor part of undergraduate and general postgraduate training. Greater awareness would lead to reduced morbidity, improved quality of life and survival outcomes in this patient group.

Key Words: common variable immunodeficiency disorders, immunoglobulin therapy, primary antibody deficiency, X-linked agammaglobulinaemia

Purpose

The main objective of this guideline is to inform clinicians about the varied and frequently complex presentations of primary antibody deficiency syndromes and to emphasise the importance of early recognition, diagnosis and referral for appropriate treatment. Specifically, the guideline offers recommendations on the identification of those patients who should be referred to clinical immunology services that are supported by expert specialist immunology laboratory services.

The guideline applies to those patients with the whole spectrum of clinical problems related to primary antibody deficiencies, with the aim of ensuring equity of access to consistently good care and has been developed for the guidance of healthcare professionals who, in their clinical practice, may encounter patients with unsuspected primary antibody deficiencies.

Implications for implementation

These guidelines are intended to impact primarily on education of healthcare professionals and their awareness of primary antibody deficiency. All clinical staff within the hospital setting should consider the possible diagnosis of primary antibody deficiency in a patient presenting with severe, persistent, opportunistic or recurrent infections or with other potential indicator conditions. The latter includes disorders of immune regulation (granulomatous, hypersensitivity or autoimmune disease), a restricted range of malignant diseases (lymphoma, skin or gastric cancer), vaccine failures or, occasionally, stigmata associated with specific deficiency syndromes.

Recognition and referral of patients with suspected primary antibody deficiency is important as appropriate therapy can prevent or reduce infections, and delayed therapy is associated with complications.

Primary antibody deficiency syndromes (Table 1)

Table 1.

B-cell defects. (a) Early B-cell differentiation defects; (b) later B-cell differentiation/function defects.

Prevalence and clinical presentation

The prevalence of clinically significant primary antibody deficiency is around 1:25,000 to 1:110,000 of the population. Overall, 95% of patients with primary antibody deficiencies present after the age of six years. A relevant history allied to appropriate suspicion and disease awareness, are the most important elements for early recognition and diagnosis of primary antibody deficiency. Patients at any age with recurrent infections (especially in the upper and lower respiratory tracts), those with infections in more than one anatomical site and those in whom the frequency or severity of infection is unusual or out of context should be investigated for possible antibody deficiency (Table 2). More rarely, granulomatous, inflammatory or autoimmune features are the initial manifestation of primary antibody deficiency. The European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) has developed an algorithm for clinicians to guide assessment and referral of possible primary immunodeficiencies, including primary antibody deficiencies.1 The UK Primary Immunodeficiency Network website contains a diagnostic tool developed from this algorithm to help clinicians assess potential primary immunodeficiency disorders (www.ukpin.org.uk).

Table 2.

Presenting symptoms of infection in cohorts of patients with primary antibody deficiencies.

Investigations

Serum immunoglobulins are the most important investigation in initial assessment. Most patients subsequently diagnosed with primary antibody deficiency have an immunoglobulin (Ig) G level of 3 g/l or less, with an IgA level of less than 0.1 g/l and in some antibody deficiencies an IgM level of less than 0.25 g/l.2,3 Over 90% of patients with the most common types of antibody deficiency, common variable immunodeficiency disorders, have an IgG level of less than 4.5 g/l at diagnosis.4

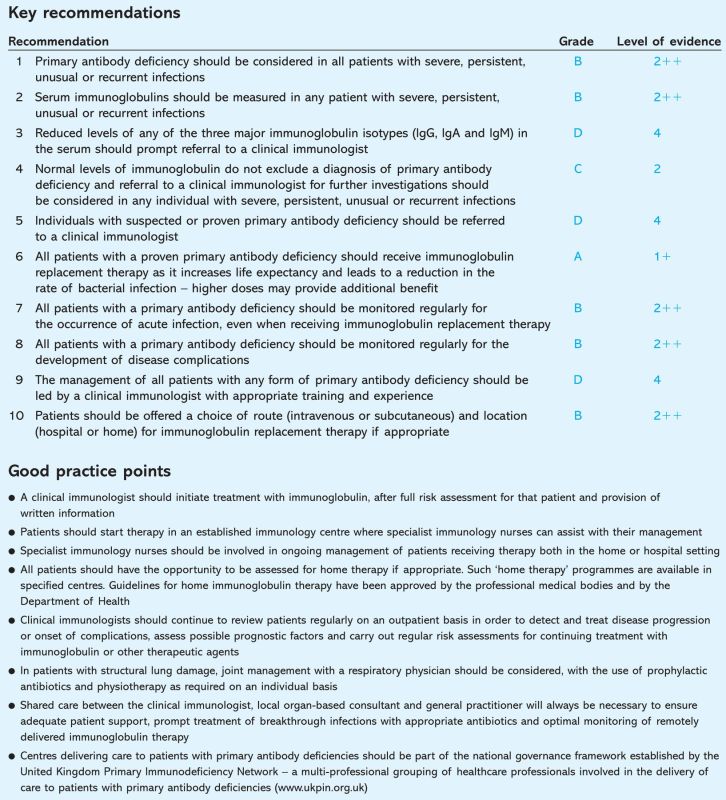

The guidelines.

Diagnostic delay

Patients with primary antibody deficiencies present to a wide variety of clinical specialties other than clinical immunology, but the diagnosis of antibody deficiency is established in far fewer patients seen in these departments than in patients seen in immunology clinics. Diagnostic delay is associated with considerable morbidity, particularly recurrent pneumonias, with secondary structural lung damage such as bronchiectasis and associated pulmonary hypertension and, ultimately, pulmonary heart disease.5

Therapy

Immunoglobulin therapy increases survival, leads to a reduction in the rate of bacterial infections, days of antibiotic usage, days of fever and hospital admissions and is equally efficacious in this respect when given by either intravenous (iv) or subcutaneous (SC) routes.2,4,6–8 Inadequate immunoglobulin replacement therapy or delayed diagnosis places the patient at greater risk of local or systemic recurrent infections. Some of the more common infections are listed in Table 3. The risk of infection remains even when appropriate therapy with replacement immunoglobulin is initiated, although this is reduced compared to untreated patients.

Table 3.

Common acute infections in primary antibody deficiency.

Complications

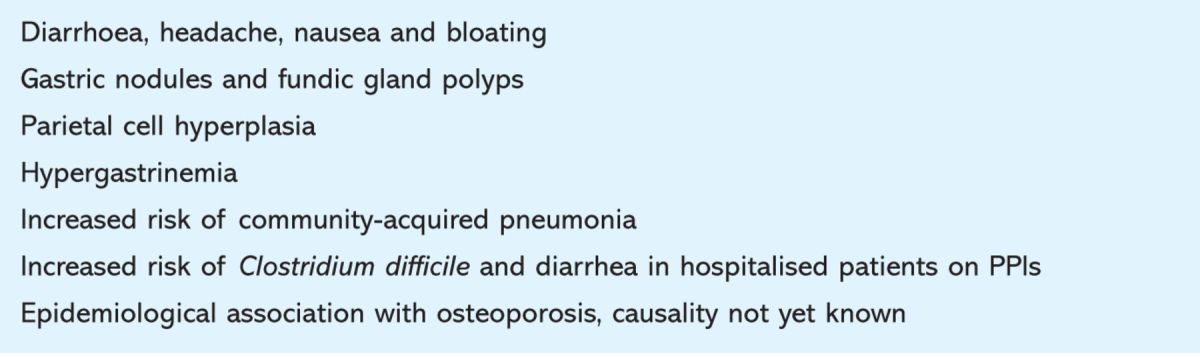

Despite therapy, patients can develop a number of organ-specific and systemic complications (Table 4), not all of which are related to diagnostic delay or inadequate replacement therapy with immunoglobulin. Some of these occur rarely and require specialist knowledge and experience for appropriate diagnosis and management.

Table 4.

Summary of organ-specific complications.

Health-related quality of life (QoL) in untreated or inadequately treated primary antibody deficiency is poor in many areas of daily life. Optimal treatment with subcutaneous immunoglobulin dramatically improves QoL to levels comparable with normal control groups.9

Individual needs

In addition to medical needs, patients often require support with issues surrounding employment, travel and other insurance, access to appropriate benefits and support for carers and families. The Primary Immunodeficiency Association provides a vital function in these areas within the UK, and all patients should be provided with information about this organisation.

Membership of the working party

Philip Wood, consultant immunologist, St James's University Hospital and chair, UK Primary Immunodeficiency Network; Richard Herriot, consultant immunologist, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and chair, Royal College of Pathologists Specialty Advisory Committee on Immunology; Alison Jones, consultant paediatric immunologist, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London; Helen Chapel, consultant immunologist and professor of clinical immunology, Nuffield Department of Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford; Janet Burton, clinical nurse specialist in immunology, Nuffield Department of Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford; Simon Stanworth, consultant haematologist John Radcliffe Hospital and National Blood Service, Oxford; Daniel Peckham, consultant respiratory physician, St James's University Hospital, Leeds; Christopher Hyde, senior lecturer in clinical epidemiology, West Midlands Health Technology Collaboration, University of Birmingham; Christopher Hughan, chief executive, Primary Immunodeficiency Association.

Funding

UK Primary Immunodeficiency Network is supported by an unrestricted grant from CSL-Behring.

References

- 1.de Vries E. Patient-centred screening for primary immunodeficiency: a multi-stage diagnostic protocol designed for non-immunologists. Clin Exp Immunol 2006;145:204–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham-Rundles C, Bodian C. Common variable immunodeficiency: clinical and immunological features of 248 patients. Clin Immunol 1999;92:34–48. 10.1006/clim.1999.4725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kainulainen L, Nikoskelainen J, Ruuskanen O. Diagnostic findings in 95 Finnish patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol 2001;21:145–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapel H, Lucas M, Lee M. et al Common variable immunodeficiency disorders: division into distinct clinical phenotypes. Blood 2008;112:277–86. 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood P, Stanworth S, Burton J. et al Recognition, clinical diagnosis and management of patients with primary antibody deficiencies: a systematic review. Clin Exp Immunol 2007;149:410–23. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03432.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eijkhout HW, van Der Meer JW, Kallenberg CG. et al The effect of two different dosages of intravenous immunoglobulin on the incidence of recurrent infections in patients with primary hypogammaglobulinemia. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter crossover trial. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roifman CM, Schroeder H, Berger M. et al Comparison of the efficacy of IGIV-C, 10% (caprylate/chromatography) and IGIV-SD, 10% as replacement therapy in primary immune deficiency. A randomized double-blind trial. Int Immunopharmacol 2003;3:1325–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapel HM, Spickett GP, Ericson D. et al The comparison of the efficacy and safety of intravenous versus subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy. J Clin Immunol 2000;20:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardulf A. Immunoglobulin treatment for primary antibody deficiencies: advantages of the subcutaneous route. BioDrugs 2007;21:105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]