Abstract

In 2010, 2,176 medical registrars in England (43%) responded to a survey of attitudes to current and future working conditions. Regarding current working, 88% were currently happy with their job with respect to their specialty but only 49% were happy with respect to acute medicine. Even if pay was increased, 59% would only want to work a 48-hour week or less. Regarding future jobs, 59% were worried about future job prospects with 91% exploring ways of extending their training. Only 36% would consider working away from their current location as a consultant, only 42% of those trained in acute medicine wish to take part in the acute take, 15% would consider a ‘sub-consultant’ post and only 60% were looking forward to becoming a consultant. The findings of this survey show that medical registrars are very concerned about their future. From their perspective, clinical medicine in England is in poor health.

Key Words: consultant, job satisfaction, medical registrar

Background

Over the past nine years the Medical Workforce Unit (MWU) of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) has sent out an annual survey to medical registrars. This survey has covered many different questions and allows insight into the concerns, working patterns and future intentions of this important professional group. The past few years have seen huge changes in the way junior doctors work with the advent of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD),1 the prospect of medical unemployment with the financial downturn and oversupply of specialists in the larger specialties.2,3 This paper reports the findings of the registrar survey for 2010.

Methods

Medical registrars (both specialty and specialist) in England were identified from the Joint Royal Colleges Postgraduate Training Board (JRCPTB) database and sent a survey questionnaire using Vovici software (2010) by email on 20 July 2010.

The questionnaire was broken down into seven sections: general demographics, education and training, working patterns, job satisfaction, research, job prospects, and the EWTD. The full survey questionnaire is available on the RCP website.

Three email reminders were sent on 28 July, 4 August and 11 August after which the survey was closed and analysed.

Results

Returned questionnaires were received from 2,176 registrars in 2010 (43%). Responses were received from registrars in all the medical specialties and from all deaneries.

Free text responses were numerous and strong emotive terminology was used by many. Areas of particular concern are summarised below. Many free text responses expressed a sense of privilege in being a doctor but also frustration at the stresses, working conditions and expectations that make the job difficult.

Demographics

Of the responding registrars 51.0% were male, of which 60.6% were training in acute (general) medicine as well as their specialty. 69.6% were working full time, 9.1% working flexibly, 14.7% were doing research, 2.9% were on maternity leave, 0.9% in locum training posts and the rest in academic posts (including academic clinical fellowships or clinical lecturers).

Education and training

Of registrars:

77.0% were involved in assessing core medical trainees, although only 65.1% had received any training in assessments (most of whom had had training by ‘observation of consultant’)

89.5% had taken study leave in the previous year, of which 59.4% was self-funded and 9.1% funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Only 18.4% had difficulty obtaining study leave

58.7% reported that their training would prepare them adequately to be a consultant with 31.9% unsure and 9.4% reporting that they felt their training would not prepare them adequately.

Regarding the use of e-portfolios, 77.6% of registrars used one (either for themselves or in assessing other trainees), of which 46.1% found it easy to use and 16.8% found it difficult to use. Navigation through different screens was reported as the most limiting factor to e-portfolio use followed by upload and click speed. Haematology registrars reported particular difficulties with e-portfolios.

Working patterns

Of registrars surveyed, 72.7% would prefer, given no increase in current pay, to work 48 hours a week or less. Only 4.2% would work more than 56 hours. Even if pay was to increase in line with current banding, 59.1% would still work 48 hours or less and only 8.4% would work more than 56 hours.

Job satisfaction

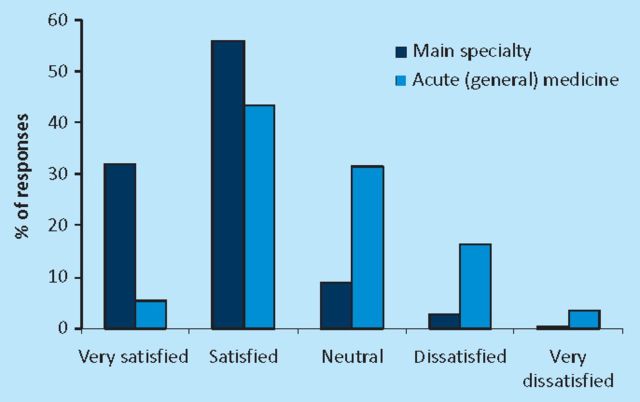

In total, 88% were either satisfied or very satisfied with their job with respect to their specialty. However, only 48.6% were either satisfied or very satisfied with their job with respect to acute medicine (Fig 1). Only 49.2% would recommend medicine as a career, compared with 55.6% in the previous year.

Fig 1.

Job satisfaction.

Research and academic medicine

Of those answering the question, 395 registrars (20.6%) considered themselves being in academic training. In total, 774 registrars reported working in ‘academic’ posts of which 78 (10.1%) were academic clinical fellowships, 44 (5.7%) clinical lecturer posts, 358 (46.3%) in ‘out-of-programme experience’ and 294 (38.0%) in ‘other posts’. Of the 684 registrars who gave information on the funding source for their academic posts, 12.4% were National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funded, 9.6% were funded by a national research council grant, 23.7% by charitable funding and the rest ‘other’.

Seven-hundred and sixty-two registrars reported having an academic supervisor, of which 71.9% were satisfied or very satisfied with the supervision provided. Four-hundred and twenty-eight registrars reported having an ‘academic mentor’ of whom 67.2% were satisfied or very satisfied with their mentor.

Job prospects

In response to questions about future consultant posts, 28.0% were very concerned about obtaining such a post, 31.1% were moderately concerned, 24.0% were neutral, and 16.8% were unconcerned. Of respondents, 90.8% were considering increasing research time or other out-of-programme activity to increase the chances of getting a consultants post. One-hundred and sixty-two registrars reported ‘knowing of a colleague with a certificate of completion of training (CCT) who had been unemployed for more than three months’.

Of respondents, 13.5% were not looking forward to becoming a consultant in contrast to 60.2% who were looking forward to being appointed. A total of 28.6% were not planning to seek a UK consultant post immediately on gaining a CCT, with 25.5% citing wanting to stay locally and thus waiting for a suitable post, 31.6% wanting to move abroad, 20.9% wanting to do further research, 10.1% not feeling prepared for such a post and 9.4% preferring to wait for a teaching hospital post. Some free text responses expressed extreme concern for the future of the NHS and the attractiveness of overseas posts in comparison.

Regarding location and type of consultant posts, 58.7% of registrars would want a consultant post in their current deanery, 5% would work in an adjacent deanery and the rest would work in any deanery. Of respondents, 46.1% would not take a less than full-time post and 20.2% would only take such a post; 43.1% would prefer a teaching hospital post, 21.4% a district general hospital post and the rest were happy to work in either setting or were undecided.

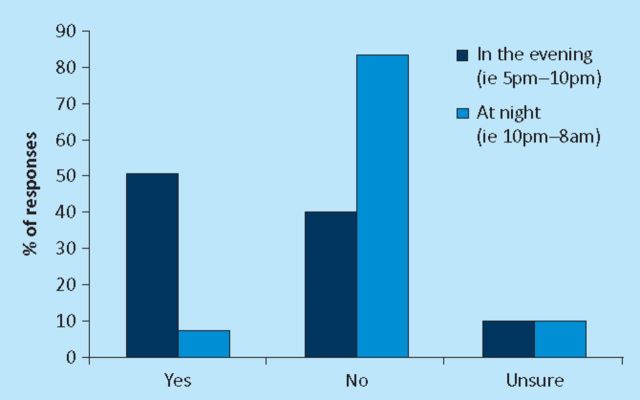

In respect of the acute medical ‘take’, 41.6% of those whom were trained to do so would wish to take part in the acute medical take on becoming a consultant, 35.4% would not and the rest were undecided. For ‘take’ (either specialty or acute medicine), 13.7% would be happy to work a rota frequency between 1:4–1:8, 45.5% to work between 1:9–1:12, 25.8 to work between 1:13–1:20, and 4.5 less frequent than this (the rest were ‘undecided’). In total, 50.5% and 7.2% would be happy to work evenings up to 10pm and overnight respectively (Fig 2). Eleven per cent believe consultants taking part in acute medical take should work overnight, 24.8% up to midnight and 45.5% up to 10pm.

Fig 2.

Would you consider being resident on-call as a consultant physician?

New types of consultant working were unpopular, with only 14.8% saying that they would take a ‘sub-consultant’ post and 64.9% stating that they would not, with the rest undecided. An acute medicine post would be taken up by 13.2% rather than one in their specialty, and 77.7% would not (the rest unsure). However, despite this reluctance, 57.3% believe that future consultants will be required to work differently from current consultants.

European Working Time Directive

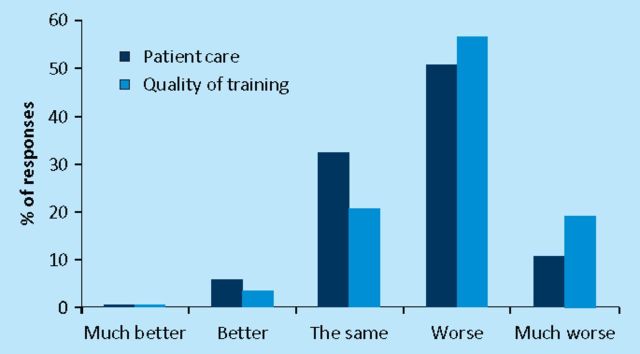

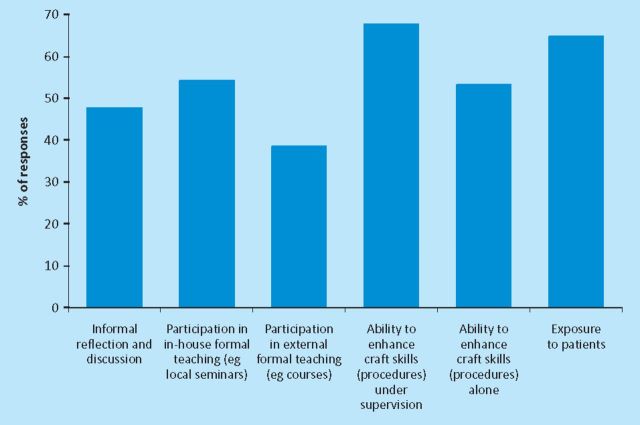

Of respondents, 86.7% reported working an EWTD-compliant rota. Most felt that the EWTD has made quality of training and patient care worse (Fig 3), with most aspects of training being adversely affected (Fig 4), but especially procedures related to the craft specialties.

Fig 3.

Effect of the European Working Time Directive on patient care and quality of training.

Fig 4.

Has the introduction of the European Working Time Directive reduced the following?

Many free text responses were received on EWTD. Some registrars in less acute specialties (eg genitourinary medicine) were very supportive of the EWTD. However, the majority of free text responses were despondent about the effect of reducing hours, especially with the need to cover for absent colleagues. Further comments about the inflexibility of training within this context and calls for lengthening training were made. There were also reports of pressure being applied to ensure rotas were reported as ‘compliant’.

Discussion

This is the largest survey of the experiences and expectations of the current body of medical registrars in England. The results reveal some very interesting trends which will have important repercussions on the registrars and consultant physicians of the future.

There is no doubt that the current economic climate in the NHS within England has created much uncertainty about the way doctors will work in the future. Further uncertainty has been created by proposed changes in the structure of the NHS by the coalition government, not least how training will be funded, quality assured and the workforce planned.4 However, it is vital to understand how the current registrars (and therefore the next generation of NHS consultants) envisage working in the future such that workforce modelling can be adjusted appropriately.

Three key themes emerge from this survey. The first of these is the acceptance that consultants will need to work differently in the future, with perhaps the creation of a new grade of specialist (or ‘sub-consultant’). Such specialists will need to provide greater out-of-hours care, and be more focused on acute medicine. However, despite this acceptance, it is clear that many future consultants are less than keen on this prospect and many may even consider going abroad to avoid such posts. It is worrying that so many registrars are not looking forward to being NHS consultants and would not recommend a career in medicine.

The second theme is that current working conditions, training and patient care are at a low ebb. While much of this can be attributed to the EWTD, it is not wholly to blame. Inflexibility of training posts,5 the growing intensity of acute medicine due to increased admissions, increasing junior doctor sickness levels,6 difficulties in obtaining locums and increased patient expectations are all contributory. There is increasing anxiety in core medical trainees in the UK about the hardships of being a medical registrar and this survey confirms that these anxieties are well founded. Considerable work needs to be done to assess how the working conditions and job satisfaction for medical registrars can be improved if clinical medicine in the UK is not to suffer a manpower crisis.

The final theme is that academic medicine seems in reasonable health. Thus, while the overall response rate for the survey was 43%, 20.6% of these specialist registrars were in academic training appointments. Moreover, some 22% of these trainees were funded by the NIHR or a national research council grant, and a further 23.7% by charitable funding. These figures have several implications. First, some 10% of respondents in this category were in academic clinical fellowship appointments, which are designed to facilitate the development of a proposal for the award of a formal training fellowship. While the success rate of such applications is as yet unclear, by implication the ‘pipeline’ of potential academic trainees is healthy. Second, the competition to gain such funding is strong; figures for the respondents in posts funded by national bodies or charities imply high quality applicants, sound mentorship/supervision and a structured programme of research likely to lead to publication and/or the submission of a higher degree. Finally, rates of satisfaction concerning supervision or mentorship were lower. It would be interesting to compare these with rates for clinical educational supervision.

In conclusion, this survey provides a clear evaluation of the current and future working lives of England's medical registrars. It shows that considerable work needs to be done to improve the ‘lot’ of this vital group of doctors. The RCP will therefore make this a priority in future workstreams.

References

- 1.House J. Calling time on doctors' working hours. Lancet 2009; 373: 2011–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goddard AF. Planning a consultant delivered NHS. BMJ 2010; 341: c6034. 10.1136/bmj.c6034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goddard AF. Consultant physicians for the future: report from a working party of the Royal College of Physicians and the medical specialties. Clin Med 2010; 10: 548–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon J. New proposals for reorganisation of healthcare staff in England. BMJ 2011; 342: d1839. 10.1136/bmj.d1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MMC Inquiry. Aspiring to excellence. Final report of the independent inquiry into Modernising Medical Careers 2008London: MMC Inquiry [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS Information Centre. Sickness absence rates in the NHS: April–June 2009 2009London: NHS Information Centre [Google Scholar]