Abstract

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a debilitating, painful condition in a limb associated with sensory, motor, autonomic, skin and bone abnormalities. Pain is typically the leading symptom, but is often associated with limb dysfunction and psychological distress. Prompt diagnosis and early treatment is required to avoid secondary physical problems related to disuse of the affected limb and the psychological consequences of living with undiagnosed chronic pain. UK guidelines have recently been developed for diagnosis and management in the context of primary and secondary care.1 The purpose of this concise guideline is to draw attention to these guidelines. Information in this article has been extracted from the main document and adapted to inform the management of CRPS as it presents to physicians in the course of their daily practice.

Key Words: clinical guidelines, complex regional pain syndrome

Background

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a debilitating condition, characterised by pain in a limb, in association with sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor, motor and dystrophic changes. It commonly arises after injury to that limb. Pain is typically the leading symptom of CRPS, but is often associated with limb dysfunction and psychological distress. Patients frequently report neglect-like symptoms or a feeling that the limb is ‘alien’.2

CRPS can be divided into two types based on the absence (type 1, much more common) or presence (type 2) of a lesion to a major nerve. The subtype of CRPS has no consequences for the general approach to management, but the cause of nerve damage in CRPS 2 should always be clarified–urgently in acute cases (see guideline 1.2).

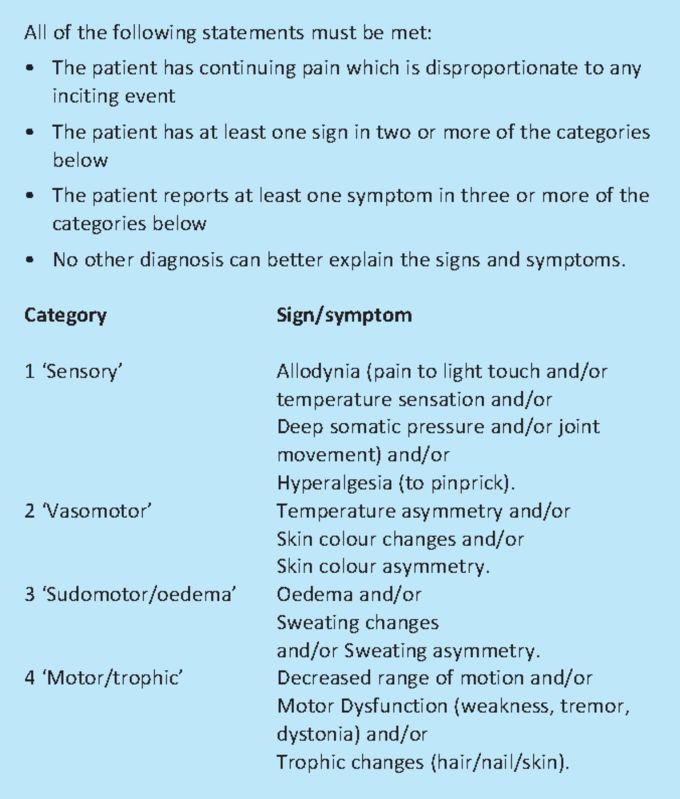

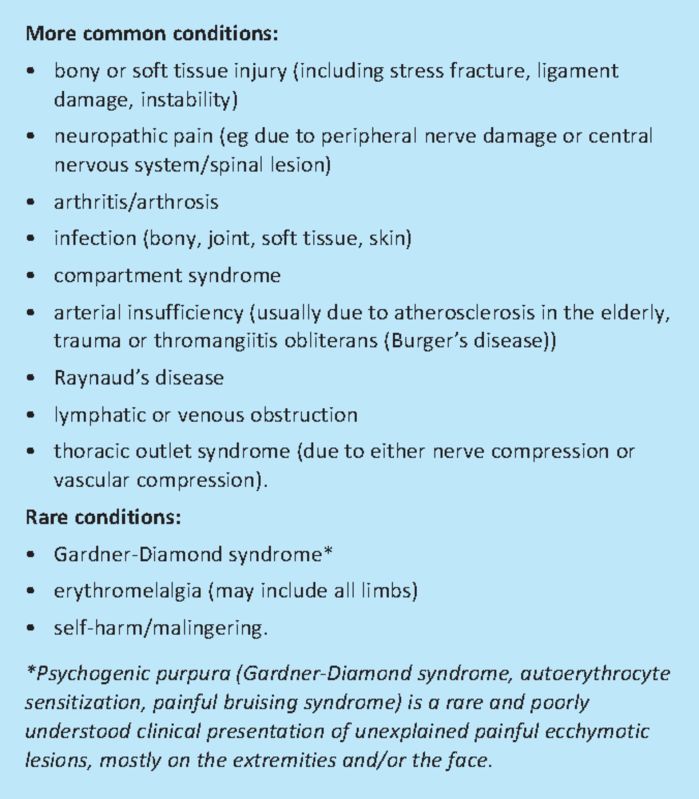

The diagnosis of CRPS cannot be made on imaging or laboratory tests. The condition is diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria3 shown in Box 1. Differential diagnoses are listed in Box 2.

Box 1. Budapest diagnostic criteria. Adapted from reference 3.

Box 2. Differential diagnoses for complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

Aetiology and course

The cause of CRPS is currently unknown.

Precipitating factors include injury and surgery. However, there is no relationship to the severity of trauma while in some cases there is no precipitating trauma at all (9%).4 The development of CRPS does not mean that surgery was suboptimal.5

Transient features of CRPS are much more common than most clinicians realise–occurring in up to 25% of minor limb injuries.6

Approximately 15% of sufferers will have unrelenting pain and physical impairment >5 years after CRPS onset, although more patients will have a lesser degree of ongoing pain and dysfunction7 impacting on their ability to work and function normally.

There is no medical cure for CRPS.

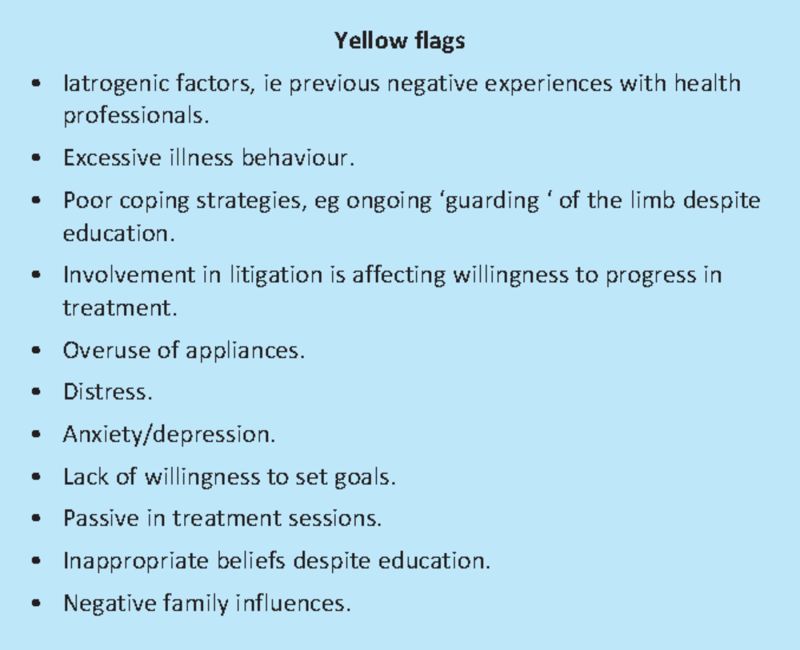

It is also now clear that CRPS is not significantly associated with a history of pain-preceding psychological problems, or with somatisation or malingering. Patients still report feeling stigmatised by health professionals who do not believe that their condition is ‘real’. However, patients may require psychological intervention and support to deal with the particularly distressing nature of CRPS symptoms. Psychosocial risk factors that may predict chronicity8 are shown in Box 3.

Box 3. Identified psychosocial risk factors (yellow flags) which may predict chronicity. Adapted from reference 9.

Treatment approach

Prompt diagnosis and early treatment is required to avoid secondary physical problems associated with disuse of the affected limb and the psychological consequences of living with undiagnosed chronic pain.10

Early referral to physiotherapy and encouraging gentle movement as early as possible, may potentially prevent progression of symptoms.11

Except in mild cases, patients with CRPS are generally best managed in specialist pain management or rehabilitation programmes.

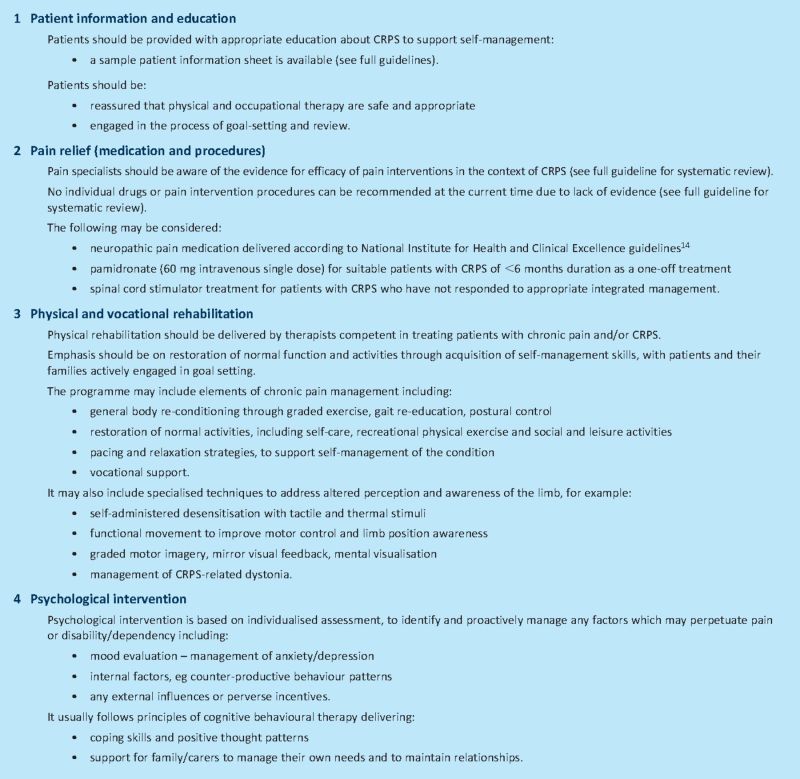

An integrated interdisciplinary treatment approach is required, including the four ‘pillars of intervention’ (see Box 4).

Box 4. Four pillars of treatment for complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)–an integrated interdisciplinary approach.

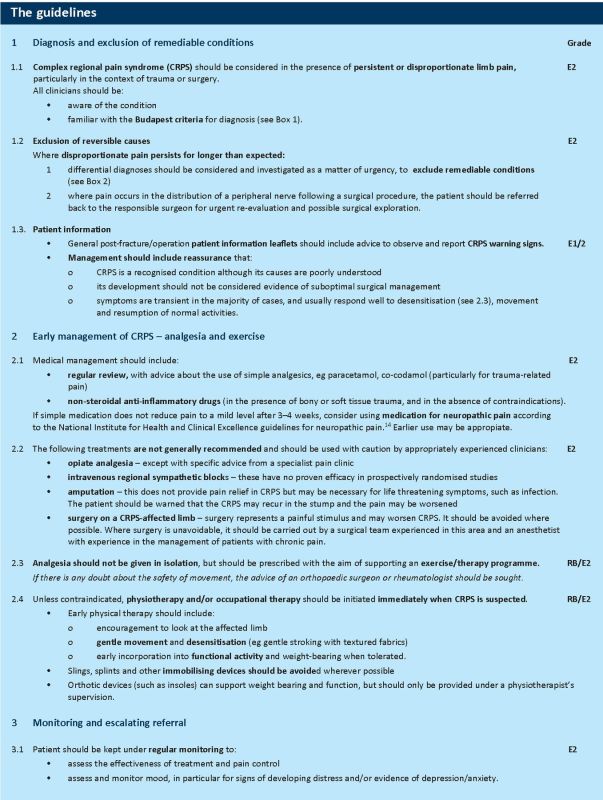

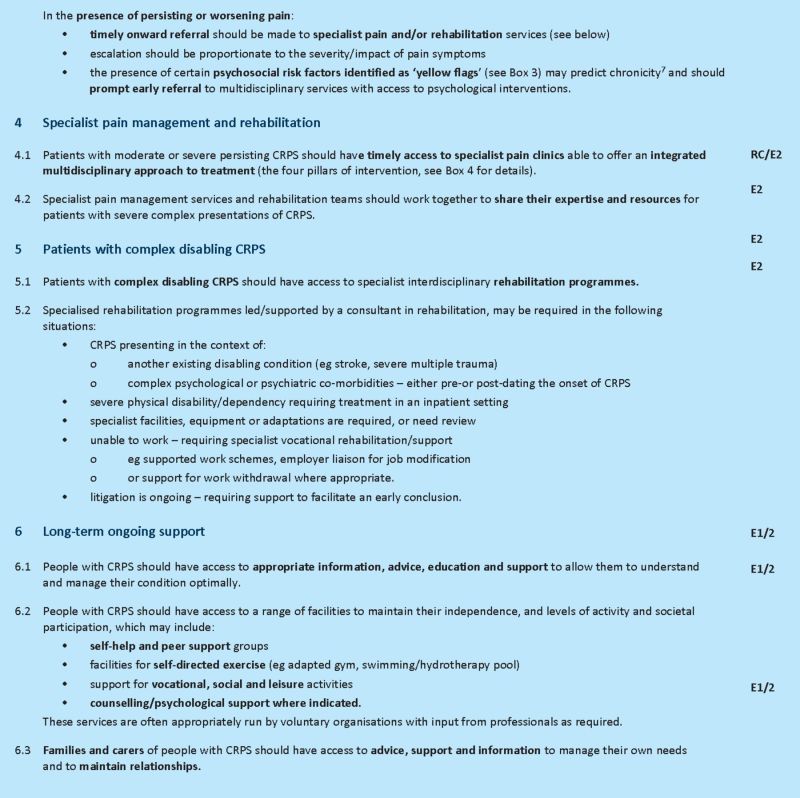

This guidance

UK guidelines have recently been developed for diagnosis and management in the context of primary and secondary care.1 Information in this concise guidance document has been extracted from the main document and adapted to inform the management of CRPS as it presents to physicians in the course of their daily practice.

The guidelines were drawn up in accordance with the principles recommended by the AGREE Collaboration.12 The methodology table is available online, and a full description of the methodology and systematic literature review may be found in the main guideline document.11 The original recommendations were developed on the basis of panel consensus and expert opinion with reference to the existing literature. Where possible, recommendations were informed by evidence from the reviews of RCTs. However, in the absence of RCT-based evidence to inform specific guidance with respect to diagnosis and management, the majority of recommendations in this document are based on the expert opinion of service users (E1) and professionals (E2) (according to the classification used by the National Service Framework for Long Term Conditions).13

Implications for implementation

The implications for implementation primarily relate to training requirements for clinical staff to recognise CRPS and make the appropriate referrals for specialist management.

Currently, access to specialist pain management and rehabilitation for CRPS is patchy across the UK. For the subgroup of patients with complex needs, there is an additional requirement for closer liaison between these services to share their expertise and resources, as well as ongoing facilities (including self-help and support groups) to assist patients to manage their own symptoms and optimise their level of physical psychological and social function.

References

- 1.Goebel A, Barker CH, Turner-Stokes L, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults: UK guidelines for diagnosis, referral and management in primary and secondary care London: Royal College of Physicians; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frettlöh J, Hüppe M, Maier C. Severity and specificity of neglect-like symptoms in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) compared to chronic limb pain of other origins. Pain 2006; 124: 184–9 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanton-Hicks M, et al. Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med 2007; 8: 326–31 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veldman PJHM, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet 1993; 342: 1012–6 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92877-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins RM.Bucholz W, Heckman JD, Court-Brown CN, et al. Principles of complex regional pain syndrome. Rockwood and Green's fractures in adults 20107th edn.London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 602–15 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atkins RM, Duckworth T, Kanis JA. Features of algodystrophy after Colles' fracture. J Bone Joint Surg 1990; 72: 105–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schasfoort FC, Bussmann JB, Stam HJ. Impairments and activity limitations in subjects with chronic upper-limb complex regional pain syndrome type I. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 557–66 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geertzen J, Van Wilgen C. Chronic pain in rehabilitation medicine. Disabil Rehabil 2006; 28: 363–7 10.1080/09638280500287437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Main CJ, Williams ACC. Clinical reviewABC of psychological medicine: musculoskeletal pain. BMJ 2002; 325: 534–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harden RN, Swan M, King A, et al. Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: functional restoration. Clin J Pain 2006; 22: 420–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oerlemans HM, Oostendorp RAB, de Boo T, et al. Pain and reduced mobility in complex regional pain syndrome I: outcome of a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial of adjuvant physical therapy versus occupational therapy. Pain 1999; 83: 77–83 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00080-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guideline development in Europe: an international comparison. J Technol Assess Health Care 2000; 16: 1036–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner-Stokes L, Harding R, Sergeant J, et al. Generating the evidence base for the National Service Framework (NSF) for long term conditions: a new research typology. Clin Med 2006; 6: 91–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. CG96 Neuropathic pain: the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in adults in non-specialist settings 2010London: NICE; www.nice.org.uk/CG96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]