Key points

Intensive care represents an expensive, limited, but increasingly necessary and in-demand resource

Decisions regarding admission are not based on concrete rules and should be determined in an interdisciplinary manner by senior clinicians, preferably in advance of or in the early phases of deterioration

Admission decisions often represent ethical challenges, especially in the acute setting where patient preferences and opinions may be difficult to obtain

Prognostication is difficult, even for experienced physicians

Scoring systems have a limited role at present

A presumption for admission should be favoured if there is clinical doubt

Background

Critical (or intensive) care involves the management of acutely ill patients who have or are at risk of organ failure.1 It is a specialty of acuity, not of organ or apparatus, dealing with heterogeneous patients and complex pathology.2 Critical care services are now an essential part of care pathways in most hospitals providing both emergency and elective care.

The demand for critical care is soaring for several reasons:

the ageing of the world's population

an increasing prevalence of comorbidities

advances in medical therapy creating ‘riskier’ treatments with more complications

the prolongation of life in those with chronic or previously terminal conditions.

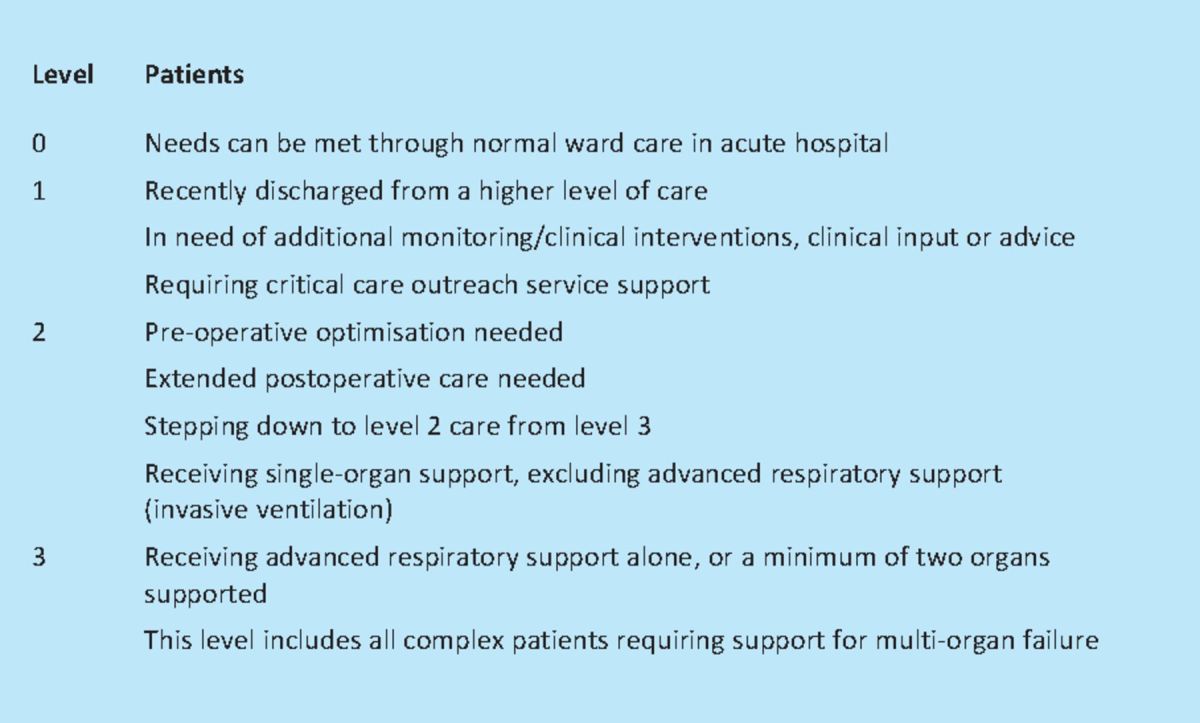

All these have created a cohort of patients who need, and increasingly expect to receive, higher levels of care (Table 1).1,3,4 Hospitals now contain an increasingly complex and unwell patient set, with ‘standard’ wards working in partnership with critical care outreach teams to manage patients at risk of or recovering from critical illness.

Table 1.

Intensive Care Society: levels of care.4

Critical care provision

The number of critical care beds in the UK has risen steadily over the last decade, but investment in critical care services remains behind that of many European countries.3 Statistics from the Department of Health situation report indicate approximately 3,700 adult and about 400 paediatric critical care beds in England, with approximately 85% of available capacity occupied at any one time.5 Local shortages can lead to reduced access, enforced transfer of critically unwell patients between institutions and the cancellation of urgent treatments or procedures (estimated at ca 10–15% of scheduled procedures).6 Morbidity and mortality are higher in those not admitted to intensive care.7 The cost of critical care is determined by the number of organs requiring support, ranging from £900/day for patients requiring single-organ support to over £1,700/day for patients requiring multi-organ support.8 As the opposing forces of supply and demand become stronger, the need for objective and ethical decisions about who is allowed access to this costly and limited resource is increasingly crucial.1

The ethics of admission

Critical care is not the panacea of common perception. Mortality remains high, especially for conditions such as acute lung injury and septic shock. Whilst technological advances allow increased intervention and prolongation of life, this may not always be beneficial or right.1 Long-term physical and psychological sequelae are common after critical illness and may persist for months to years (see accompanying article: Sequelae and rehabilitation after critical illness pp xxx–xxx). This makes determining who should receive intensive care a complex issue. Decisions surrounding admission are normally driven by individual need, but may be tempered by societal responsibility. They must take into account religious, legislative, cultural and personal factors, together with the opinion of different members of the multidisciplinary team. Above all, decisions must be objective, ethical and transparent. This represents a significant challenge when time for reflective and collaborative decision making is limited.

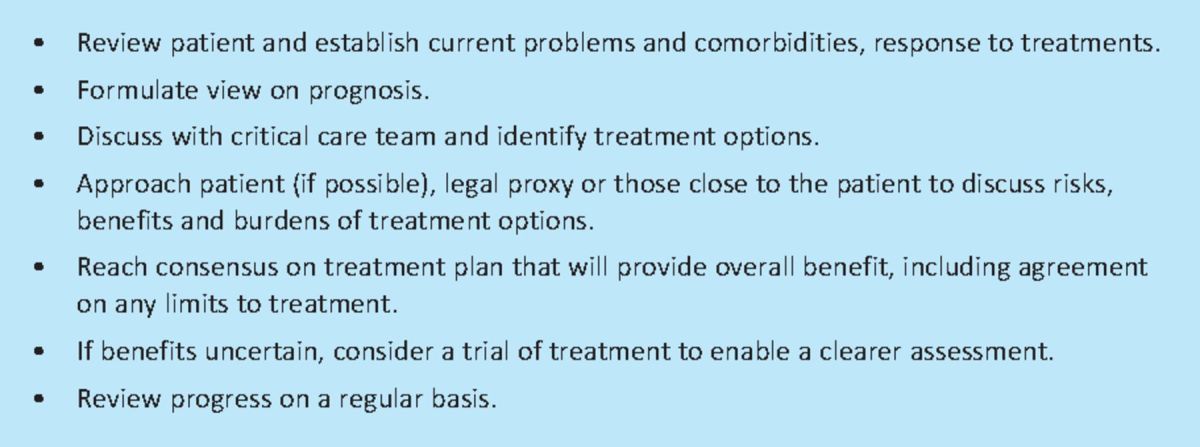

Advance care planning with patients suffering chronic progressive diseases, ideally when stable and led by teams known and trusted by the individual, may maximise the effectiveness of critical care resources and minimise the burden of end-of-life care on patients and families.9 Early establishment of treatment ceilings in acute admission is preferable, as opposed to after deterioration. Interdisciplinary algorithms for common problems and close interface between medical specialties, intensivists and often palliative care may optimise treatment practice (Table 2).10

Table 2.

Decisions surrounding admission to critical care.

Principles of admission

The General Medical Council's guidance documents provide helpful guidance on the ethical and legal aspects of decision making in this setting.11,12 The increasing complexity of the patient population and perpetual modification of disease trajectories via novel therapies have ensured it is rare for the decision to be clear-cut. Diseases previously considered incurable are evolving into chronic conditions, with critical care being a necessary bridge to achieving therapeutic targets.

In this environment, questions regarding ceilings of treatment and value judgements of which life-sustaining treatments are justified are increasingly difficult.9,10 Prognostication without, and even with, expert input is often difficult, especially in the setting of acute brain injury. Decisions either to commence or, more frequently, withhold life-sustaining therapy in this situation are inherently more complex.

The first step in the decision-making process is for the referring physician and critical care team to consider the treatment options and potential risks, benefits and burdens of each available option. Information about the current illness, underlying diseases/comorbidities, response to treatment so far and patient's general health status may be helpful in determining which options may potentially be of benefit. These treatment options, their risks, benefits and burdens should then be discussed with the patient if the patient has capacity, so they can make an informed treatment choice. Clinicians should be honest and realistic during discussions and respect the patient's right to choice. Doctors cannot be forced to provide treatment that is not clinically appropriate. Where there is disagreement about whether a particular treatment for an individual patient will provide overall benefit a second opinion can be helpful in reaching consensus, if time permits.

Decisions for patients who lack capacity

Making decisions about treatment and care for patients who lack capacity is governed in England and Wales by the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and in Scotland by the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. Enquiries should be made to establish if the patient has a valid advanced directive or has nominated a legal proxy with authority to make decisions about medical treatments.13,14 In their absence, the clinician responsible for the patient's care must decide which treatment will provide overall benefit to the patient. The clinician is required to consult with members of the healthcare team and those close to the patient to inform their decision making. In doing this, the clinician should seek to establish what would have been the patient's wishes, preferences, feelings, beliefs and values if they had capacity. All this information must be weighed up by the clinician to determine which treatment pathway would provide overall benefit to the patient.

Balancing individual needs with resource limitation

The availability of critical care resources varies significantly with location, and this variation is known to alter the indications and threshold for admission to critical care.9 Despite this, the availability or lack of beds should not alter the ethical principles that guide the distribution of existing resources or, in other words, the process through which a decision is made.

The American Thoracic Society has attempted to outline the principles governing allocation of critical care resources.15 These principles state that:

critical care, if ‘medically appropriate’, is an essential component of basic healthcare and should be provided

there is a limitation in the duty to any given individual if it unfairly compromises care to others.

Critical care unit structure and function

In the UK, in common with Europe and Australasia, a ‘closed’ model of critical care is most frequently utilised. Specialised intensive care physicians act as the consultant in charge of care for the period the patient is in the intensive care unit (ICU). Admission and discharge decisions to/from ICU are the responsibility of the critical care team. However, best practice involves a collaborative approach between the critical care team and referring physician.

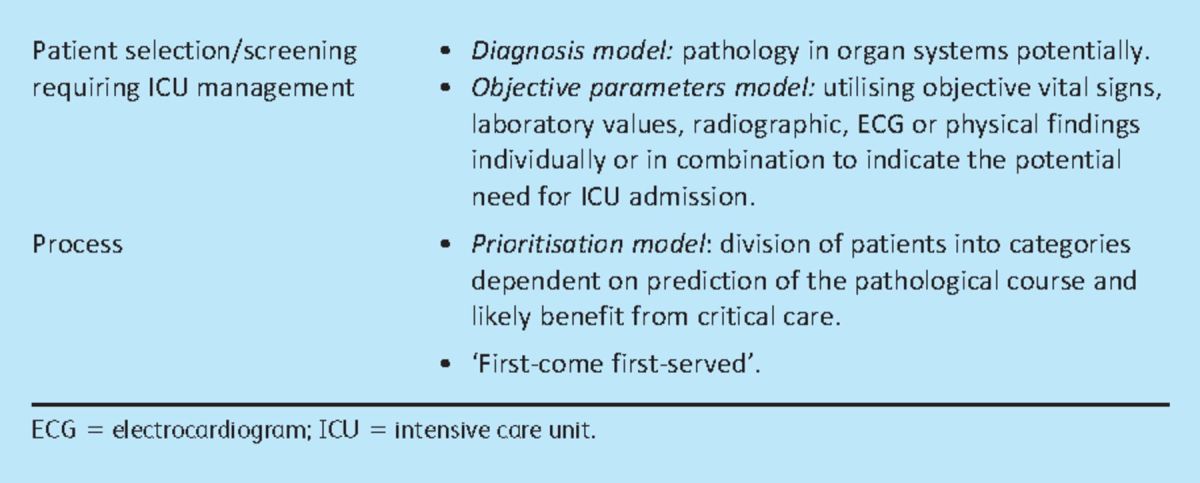

The American College of Critical Care Medicine describes different models of admission selection (Table 3),16 of which the ‘prioritisation’ model is almost universally employed by intensive care physicians. This relies on clinician synthesis of all available information on patients referred to intensive care, and their relative weighting in terms of need for critical care admission, urgency of intervention and presence of therapeutic limits. Those with the greatest and most urgent need and no pre-established treatment limitation will be admitted in advance of others.

Table 3.

US models of admission.16

Intensive care admission is often refused to those either ‘too well’ to require critical care input or ‘too sick’ to benefit.17 The central problem, however, is the absence of definitive, objective, evidence-based metrics to evaluate into which category a patient falls. The population eligible for admission is not homogeneous. Comparison at the individual level between those with different demographics, comorbidities and disease is challenging.2 Critical care units are recommended to have explicit and written criteria for admission18 but, even when in place, there remain issues surrounding their interpretation and application. Experienced clinicians should be the final arbiters of admission decisions. It is, however, well recognised that this system is not perfect.

The literature demonstrates that bias and chance play a large role in the process. This may arise from bed availability, incidence of admission requests, season, local organisational factors and physician perception of prognosis, amongst others.10,17,19 Further important factors are from where a patient is referred and the stage in their disease course.

Early detection of critical illness and the timely institution of appropriate care can reduce morbidity, mortality and length of stay.20 Identification of at-risk patients and referral to relevant senior specialists or the critical care service is often delayed, especially on general wards.21 This reduces the opportunities to prevent further deterioration and improve outcomes, and may bias the decision whether or not to admit the patient.

Role of scoring systems

Scoring systems have been developed to measure the severity of illness and predict patient outcome. Examples include the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE II and III) mortality prediction models and simplified acute physiology (SAPS) prognostic systems. These tools are useful for comparing outcomes in populations of patients receiving intensive care, but none has sufficient precision to be used reliably to determine whether to admit an individual patient to intensive care.22

Early warning scoring systems facilitate the early detection of critical illness. These are based on derangements of physiological variables such as heart rate, blood pressure and respiratory rate. Examples include:

Early warning score (EWS).

Modified early warning systems (MEWS).

Whilst some studies have shown improved health outcomes, the optimal system is yet to be established.24

Conclusions

There are no concrete rules about who should or should not be admitted to critical care. Decisions are multifactorial and often ethically challenging but frameworks exist to help guide this process (Table 3). Medical teams should engage in discussions with the critical care team regarding appropriate levels of care at the earliest possible opportunity. The default position should be admission where there is clinical and prognostic uncertainty about whether admission will provide overall benefit to the patient. Resource limitation may impinge on, but should not determine admission.

References

- 1.Vincent JL. A critical look at critical care. Lancet 2010; 376: 1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent JL, Singer M. Critical care: advances and future perspectives. Lancet 2010; 376: 1354–61 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60575-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 2010; 376: 1339–46 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60446-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. www.ics.ac.uk/intensive_care_professional/standards_and_guidelines/levels_of_critical_care_for_adult_patients.

- 5. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Statistics/Performancedataandstatistics/EmergencyActivityandCriticalCareCapacity/index.htm (last accessed May 2011)

- 6.Department of Health. Quality critical care: beyond ‘comprehensive critical care’ A report by the Critical Care Stakeholder Forum 2005London: DH; www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4121049 (last accessed May 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simchen E, Sprung CL, Galai N, et al. Survival of critically ill patients hospitalized in and out of intensive care. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 449–57 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253407.89594.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groves J. Commissioning and contracting for critical care from 2011–12: le ‘Payment by results’ est arrivé. JICS 2010; 11: 285–7 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis JR, Vincent JL. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet 2010; 376: 1347–53 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60143-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Bergwelt-Baildon M, Hallek MJ, Shimabukuro-Vornhagen AA, Kochanek M. CCC meets ICU: redefining the role of critical care of cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2010; 10: 612. 10.1186/1471-2407-10-612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.General Medical Council. Treatment and care towards the end of life: good practice in decision making 2010London: GMC [Google Scholar]

- 12.General Medical Council. Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together 2008London: GMC [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU. Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30: 770–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1211–8 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fair allocation of intensive care unit resources. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 1564 Pt 11282–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines for intensive care unit admission, discharge and triage. Crit Care Med 1999; 27: 633–8 10.1097/00003246-199903000-00048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capuzzo M, Moreno RP, Alvisi R. Admission and discharge of critically ill patients. Curr Opin Crit Care 2010; 16: 499–504 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32833cb874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health National Executive. Guidelines on admission to and discharge from intensive care and high dependency units 1996London: DH [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quartin AA, Calonge RO, Schein RM, Crandall LA. Influence of critical illness on physicians' prognoses for underlying disease: a randomized study using simulated cases. Crit Care Med 2008; 36: 462–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subbe CP, Williams E, Fligelstone L, Gemmell L. Does earlier detection of critically ill patients on surgical wards lead to better outcomes? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005; 87: 226–32 10.1308/003588405X50921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McQuillan P, Pilkington S, Allan A, et al. Confidential inquiry into the quality of care before admission to intensive care. BMJ 1998; 316: 1853–8 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guest T, Tantam G, Donlin N, et al. An observational cohort study of triage for critical care provision during pandemic influenza: ‘clipboard physicians’ or ‘evidence based medicine’? Anaesthesia 2009; 64: 1199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith GB, Prytherch DR, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI. Review and performance evaluation of aggregate weighted ‘track and trigger’ systems. Resuscitation 2008; 77: 170–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansen JO, Cuthbertson BH. Detecting critical illness outside the ICU: the role of track and trigger systems. Curr Opin Crit Care 2010; 16: 184–90 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328338844e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]