Abstract

This article describes the differences in training and departmental function between the specialties of emergency medicine in China and acute medicine in the UK, based on the experience of a visiting international medical graduate from Shanghai.

Key Words: acute medicine, emergency medicine, international medical graduate, medical education

Introduction

In June 2004, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed by Lord Warner (then Minister of Health) with the Ministry of Health in Beijing and the Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau.1 One outcome of this MoU was a two-month attachment of four Shanghainese doctors to the Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospital, jointly arranged by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) and the Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau.2 This article reflects the experience of one of those international medical graduates, facilitated by the RCP's International Office to undertake this attachment and will discuss the differences between the UK and Chinese medical systems with particular reference to acute and emergency medicine.

The emergency system in China

Emergency medicine in China developed around 20 years ago and equates to the UK's accident and emergency (A&E) departments. The Chinese Ministry of Public Health did not set up a unified criterion for emergency medicine, so there are many different models across the country. For example, in Shanghai, Peking and Guangzhou, hospital and ambulance systems work separately. In other cities (not all) the ambulance system may belong to the biggest hospital of that region and be run by that hospital's deploy centre for the ‘120’ rescue call (equivalent to ‘999’ in the UK).3

The Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau has developed a unique standard, which may change the face of emergency medicine in China, such that each emergency department (ED) has its own intensive care unit (ICU). Thus, in Shanghai each ED consists of an A&E department, an observation room (OR) and an ICU providing a seamless system of care for critically ill patients.4

The ED of Changzheng Hospital is typical of those in Shanghai. It has over 100 beds, comprising an A&E unit of 40 beds including a three-bed ‘rescue unit’, a 40-bed observation room and a 29-bed ICU. The absolute number of beds fluctuates to cope with demand which is increasing due to the large number of sick elderly requiring admission. This often means that some patients have to use trolleys as temporary beds. Most patients are first triaged by a senior nurse practitioner before being seen by a doctor from the appropriate specialty. The OR is similar to a UK medical assessment unit (MAU) and accepts acute medical admissions but without any defined time-limit target, such as the four-hour trolley waiting time which, in the UK, has improved patient throughput in the ED.5 Patients with a life-threatening condition will be sent directly to the rescue room for initial assessment and, if necessary, resuscitation and emergency surgical intervention. They will then be sent to the ICU for further life support and primary disease therapy if required.

In Shanghai Changzheng Hospital, the rescue room and ICU are both staffed by doctors from the intensive care and emergency medicine departments who can provide integrated care between the two units. This staffing model, however, is not common in China and it may be some time before it becomes so.4

What are the differences between the UK and Chinese systems?

Unlike China, all NHS hospitals with an A&E department are staffed by a separate cadre of emergency doctors who may treat a wide range of patients without referral to internal medical or surgical specialists. The assessment and initiation of management of ED attendees in Shanghai is not restricted by a four-hour trolley waiting time initiative as in the UK.

The Manchester Triage System, which colour codes cases as red, orange, yellow or green based on clinical urgency6 is widely used in the UK but is not familiar in Shanghai. Whereas in the UK some patients may be triaged to be seen by a nurse practitioner this is not available as an alternative in Shanghai. The UK triage system largely determines the urgency, based on clinical need, with which patients will be seen by a doctor in A&E and not which specialty they will be referred to as in Shanghai. Subsequently, of course, in the UK A&E doctors may refer patients on to be seen by other specialists.7

It is not possible to tell which of these two very different styles of patient care provides better outcomes – joint care between ICU and other medical specialists as in the UK or sole care by emergency medicine intensivists as in Changzheng Hospital – as they exist in very different healthcare systems.

While the UK has embraced the philosophy of early discharge and admissions avoidance as means of helping to improve bed management, all of the tertiary hospitals in Shanghai (indeed all hospitals in China) have a bed occupancy problem, especially within the A&E department. The absence of any nationwide provision of general practice means that for the majority of the population their first contact with the medical service will be at their local hospital. Despite being warned of the risks of nosocomial infection there is an apparent belief that hospital admission is the safest choice and hence demand exceeds capacity. China also lacks other community care (medical and social) schemes to support early discharge or prevent admission, for example Shanghai has no equivalent of the UK short stay MAU or intermediate care, very limited care home places and has only recently started to train general practitioners (GPs) with 1,057 GPs in 2005 and a target of training 7,000 by 2010. Of course other sociocultural differences may also play a part, such as the larger involvement of medical insurance schemes in China.

Another notable difference between the UK and China is the strong doctor–patient relationship in the UK compared to the large element of distrust that occurs in China due to concerns over abilities to afford healthcare and apparent unnecessary investigations and prescribing. The latter issues in China may largely be attributable to primary care acting as a gatekeeper in the UK, combined with a structured system for communication between different healthcare providers (primary–secondary care, secondary–primary care, and secondary–secondary care) and no similar provision in China. China has no equivalent of the NHS Plan, which requires doctors to provide patients with copies of correspondence about themselves which, coupled with the relative absence of primary care, means there is no requirement to provide discharge summaries and this absence of information transfer between different healthcare providers (even within the same hospital) leads to duplication of investigations, poor medications management and unnecessary admissions.8

Education and training for emergency medicine in China and the UK

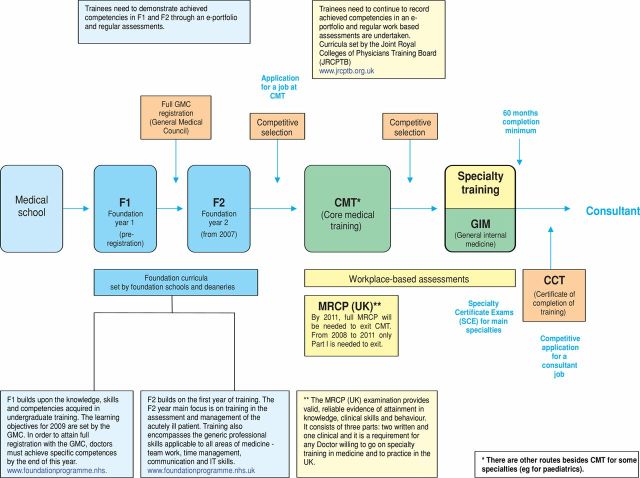

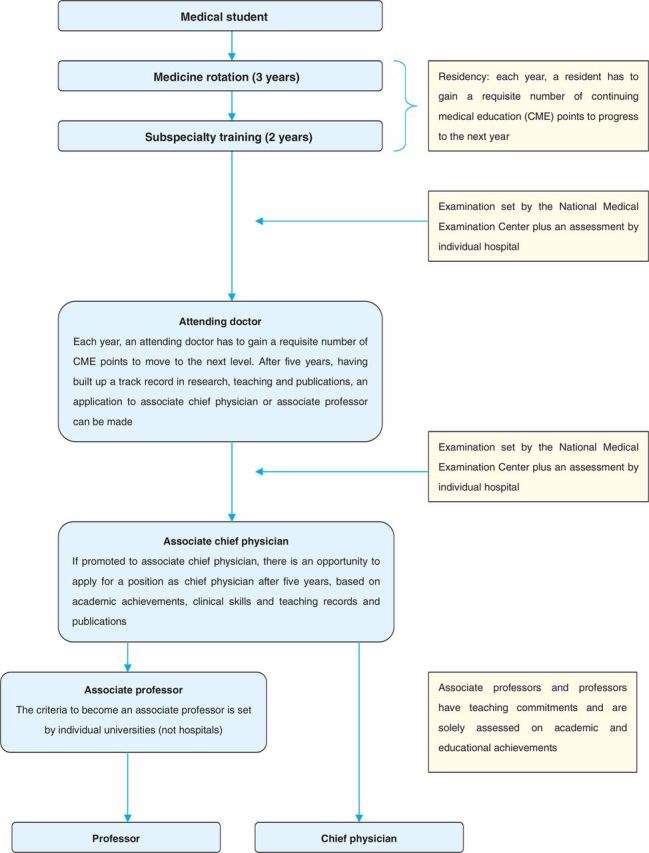

There are again some similarities and differences between the two countries and the two training models (Figs 1 and 2). This section will describe the Chinese model. Undergraduate medical training in China takes five years. Each semester, universities set their own curriculum with the common teaching materials offered by the Ministry of Education, including basic theory, clinical skills and clinical clerkship. However, every student has to pass the National Medical Licensing Examination (NMLE) held by the Ministry of Health to become a certified doctor. The NMLE consists of two parts, a clinical skills (CS) test and a general written (GW) test. Candidates are not permitted to practise medicine until they have passed both tests in the same year and applied for licence registration. CS usually takes place in July and GW in September for candidates who have undertaken regular medical undergraduate education in an institute of higher learning, and have served at least one year on probation in an institute of medical treatment, prevention or healthcare under the supervision of a medical practitioner.9 After passing the NMLE they will start a three-year medical rotation. This used to be in a hospital to which they were allocated but is now carried out only in certified hospitals. At the end of this rotation, entry to a further two-year subspecialty training post is by competitive interview only, with an opportunity for the doctor to move between hospitals. However, once they find a hospital to work in, it may be the only hospital they work in thereafter, because it is difficult to transfer from one hospital to another. Throughout these five years, progression from one year to the next is dependent upon the trainee accumulating an appropriate number of continuing medical education (CME) points. After subspecialty training they are eligible to become a specialist (attending doctor) in their chosen area of interest, in this instance emergency medicine, provided that they pass the National Health Professional Technical Qualification Exami-nation (NHPTQE moderate level), set by the National Medical Examination Center, plus an assessment by their individual hospital.10–12 As the subspecialty of emergency medicine is relatively new, however, not all doctors in this field have gone through this training programme, for example they may have trained in internal medicine or general surgery before they became emergency doctors.13–14 (ML, for example graduated as a postgraduate in cardiac surgery but now works as an emergency doctor in a large hospital in Shanghai.) Each year, an attending doctor has to gain a requisite number of CME points to move to the next level. After five years, having built up a track record in research, teaching and publications, an application to associate chief physician or associate professor can be made. For the position of associate chief physician the individual must pass the NHPTQE senior level, plus an assessment by their individual hospital, while individual universities decide if the doctor has suitable teaching and research credentials to be an associate professor. If promoted to associate chief physician, there is an opportunity to apply to be a chief physician after five years, based on clinical skills, academic achievements, teaching record and publications. Associate professors and professors are purely judged on their academic and teaching record.

Fig 1.

Clinical career path in medicine (UK).

Fig 2.

Flowchart outlining career progression in China.

A particular difference between our two postgraduate training programmes is the more rigorous and goal-orientated structure in the UK, with greater quality control of the UK training programmes through clinical appraisal and continued professional development (CPD), overseen by the royal colleges and the General Medical Council (GMC).15–16

Summary

The international medical graduate scheme offers a unique opportunity for sharing experience and providing skills not otherwise available to colleagues from overseas. Despite significant achievements in improving the health status of the Chinese population in recent decades, significant inefficiencies remain within the healthcare system. As China enters into a major phase of health system reform, this is an excellent opportunity for the RCP to share its experience in developing and maintaining postgraduate training programmes, CPD, clinical audit systems, appraisal and revalidation with Chinese colleagues.

While the prevalence of diseases may vary across the world the diseases are, in general, no different. Likewise, national healthcare policies may vary but the delivery of the necessary training programmes, eg for emergency medicine or geriatric medicine, will show little difference whatever the country.

References

- 1.China–Britain Business Council . www.cbbc.org/the_review/review_archive/sectors/33.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians International Focus Number 16, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong S. Discussing the development of emergency medicine in China at the start of a new century.. Chinese Crit Care Med 2001;13:195–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau The quality control standard for intensive care unit of emergency department in Shanghai. Shanghai: Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein M, Barmania N, Robin J, et al. Reforming the acute phase of the inpatient journey.. Clin Med 2007;7:343–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackway Jones K. Emergency triage, 1st edn London: BMJ Publishing Group, 1997 10.1097/01.NCQ.0000263109.00473.3e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHugh DF, Dricoll PA. Accident and emergency medicine in the United Kingdom.. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:702–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health The NHS Plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: DH, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National People's Congress Law of the People's Republic of China on medical practitioners, chapter 2, article 9, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Personnel Notification of enhance health professional technical qualification identification, Issue 114, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health Interim regulation for the clinical medicine professional qualification examination, Issue 462, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health Interim regulation for the preventive medicine, general medicine, pharmacy, nursing and other health disciplines professional qualification examinations, Issue 164, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CY, Wang J, Sun CY, et al. Development of modern emergency medicine education in our country.. Pract Prevent Med 2006;13:452–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui HZ, Deng LZ, Chen LQ, et al. Attach important to the higher education of emergency medicine in China.. Modern Hospital 2005;5:103–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houry DE, Ponts PT. The value of the out-of-hospital experience for emergency medicine residents.. Ann Emerg Med 2000;36:391–3. 10.1067/mem.2000.109833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dykstra EH. International models for the practice of emergency care.. Am J Emerg Med 1997;15:208–9. 10.1016/S0735-6757(97)90107-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]