Key Points

Diabetes is associated with significant microvascular complications: retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy

Diabetic retinopathy remains the most common cause of blindness in working-age adults in the developed world.

Early aggressive treatment of microalbuminuria reduces the risk of the development of nephropathy

Neuropathy may manifest in different ways and can be difficult to manage

Prevention and reduction in progression of microvascular complications requires intensive management of glucose, blood pressure and lipids

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is characterised by organ dysfunction arising directly or indirectly from the effects of chronic hyperglycaemia. The chronic complications of diabetes are traditionally classified as macro- or microvascular depending on the underlying pathophysiology. The microvascular triad of retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy is unique to diabetes.1 Most patients with diabetes will have one or more of these as overt or subclinical manifestations during the course of their disease. This review aims to give a broad overview of diabetes-related microvascular disease.

Pathophysiology

The underlying driver of microvascular disease is tissue exposure to chronic hyperglycaemia. Landmark clinical trials such as the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) and Diabetes Control of Complications Trial (DCCT) have established a clear relationship between microvascular disease and glucose control.2,3 Microvascular disease tends to occur predominantly in tissues where glucose uptake is independent of insulin activity (eg kidney, retina and vascular endothelium) because these tissues are exposed to glucose levels that correlate very closely with blood glucose levels.1 The development of disease is the result of a combination of direct glucose-mediated endothelial damage, oxidative stress due to superoxide overproduction, and the production of sorbitol and advanced glycation end-products due to the prevailing state of hyperglycaemia.1,4 These metabolic injuries cause altered blood flow and changes in endothelial permeability, extravascular protein deposition and coagulation resulting in organ dysfunction. Current evidence demonstrates a clear relationship between blood pressure (BP) and progression of nephropathy5 and retinopathy.6 These are now established as independent risk factors for microvascular disease progression.

Diabetic retinopathy

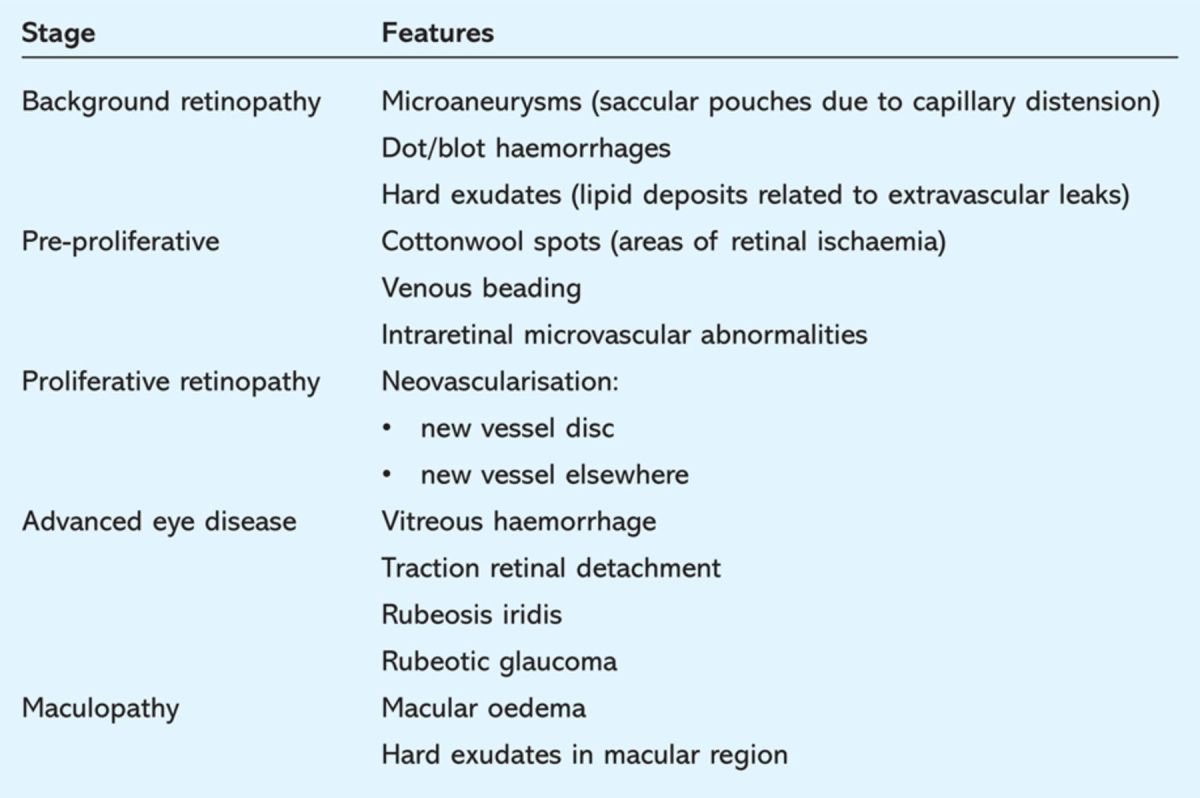

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of visual loss in working-age adults in the developed world. It occurs following hyperglycaemia-mediated damage within the retinal microvasculature. This damage causes basement membrane thickening, increased capillary permeability and the formation of microaneurysms. These changes lead to intravascular coagulation, resulting in retinal ischaemia which drives the formation of new vessels within the retina (neovascularisation). These new vessels are fragile and may rupture causing retinal bleeds. Furthermore, the lack of lymphatic drainage within the retina causes fluid accumulation in the presence of hyperglycaemia resulting in macular oedema. Macular oedema can be associated with any of the aforementioned stages. The classification of different forms of retinopathy is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification of diabetic retinopathy.

The UKPDS trial highlighted that up to 40% of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) have some retinopathy at the time of diagnosis, reflecting late presentation in this group. This contrasts with epidemiological data in which the prevalence varies from 16–95% depending on duration of diabetes.7 Diabetic retinopathy is rare in newly diagnosed patients with T1DM where the presentation is more acute. Diabetes duration, glycaemic control and BP are the strongest risk factors for the development and progression of retinopathy. There is some evidence that rapid improvements in glycaemic control can cause transient worsening of retinopathy.8 In patients with advanced retinopathy improvements in glycaemic control should therefore be gradual.9,10 Retinopathy is known to deteriorate during pregnancy;11,12 these patients need to have retinal assessments soon after their first appointment and again in the 28th week of pregnancy.13

Management

Pan-retinal photocoagulation, introduced in the early 1970s, is the treatment of choice for proliferative and pre-proliferative retinopathy. This procedure coagulates the ischaemic retina which acts as the driving factor for new vessel formation (presumably by reducing vascular endothelial growth factor. Focal laser treatment is also used in macular oedema to reduce vascular leakage. Laser treatment can bring down the five-year incidence of blindness from 50% to 5%,14 but at the expense of losing up to 50% of peripheral vision10 – with possible implications for driving licence holders.

Nephropathy

Diabetic nephropathy arises from the combination of hyperglycaemia and hypertension driving glomerular damage. The underlying pathological changes involve thickening of basement membrane, atrophy, interstitial fibrosis and arteriosclerosis.15 This initially results in glomerular hyperfiltration and subsequently progressive loss of renal function.16 Diabetic nephropathy occurs in 30–40% of patients within 25 years.17 It is not understood why some individuals with ‘poor control’ are protected against renal disease.

Microalbuminuria

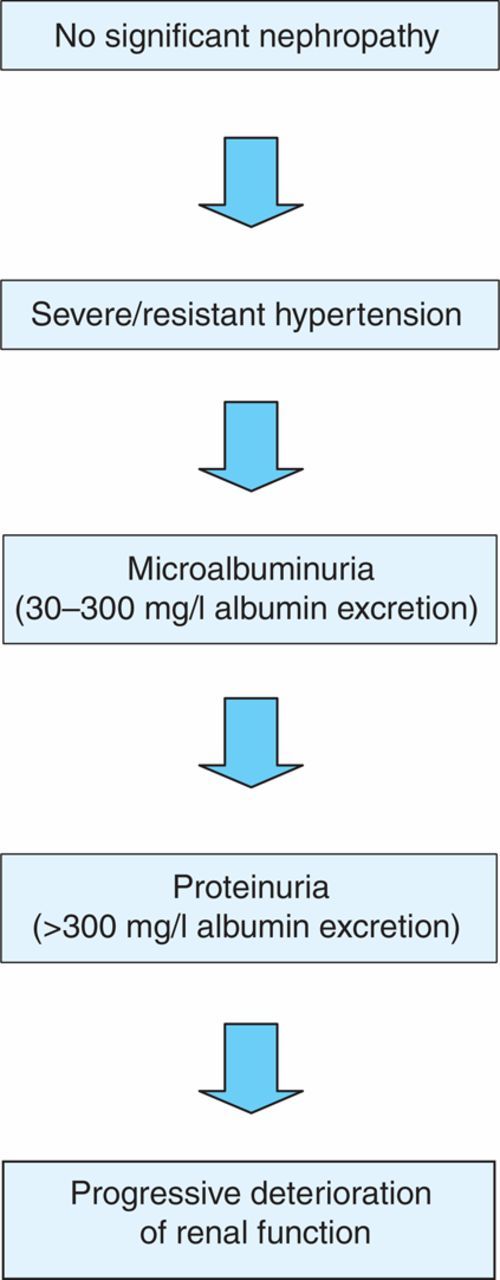

Increased glomerular filtration pressures result in albuminuria, a driver for ongoing renal damage.16 Microalbuminuria (Fig 1) is the first step towards developing overt proteinuria, but only 20% of patients with the condition progress towards proteinuric nephropathy.15 Proteinuric nephropathy continues to have a poor prognosis, with most patients dying from cardiac disease or progressing to end-stage renal failure. Furthermore, proteinuria is a marker of vascular endothelial dysfunction and there is a good correlation between cardiovascular risk and degree of albuminuria. The presence of microalbuminuria should therefore prompt clinicians to manage all cardiovascular risk factors aggressively. Criteria for referrals to nephrology services need to be defined so that these patients can be referred in a timely manner and their care optimised.

Fig 1.

Progression of nephropathy

Management

Aggressive blood pressure reduction is of vital importance in managing diabetic nephropathy. Individuals with microalbuminuria need to have BP ≤=125/75.18 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are first line agents for treating hypertension with numerous trials showing their effectiveness in reducing proteinuria and deterioration of renal function,19–21 but often multiple blood pressure lowering agents are required. Early studies suggested that combining ACEIs and ARBs was superior to monotherapy in reducing proteinuria,22but recent evidence highlights increased side effects (hyperkalemia and renal impairment) of combination therapy with quite modest outcome benefits.23,24 Both the UKPDS and the DCCT have demonstrated the importance of glycaemic control in retarding progression of nephropathy, whereas the evidence for positive outcomes with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol reduction appears less clear. Patients with worsening proteinuria or deteriorating renal function will need to be seen by nephrologists to ensure that renal replacement therapy can be planned appropriately.

Neuropathy

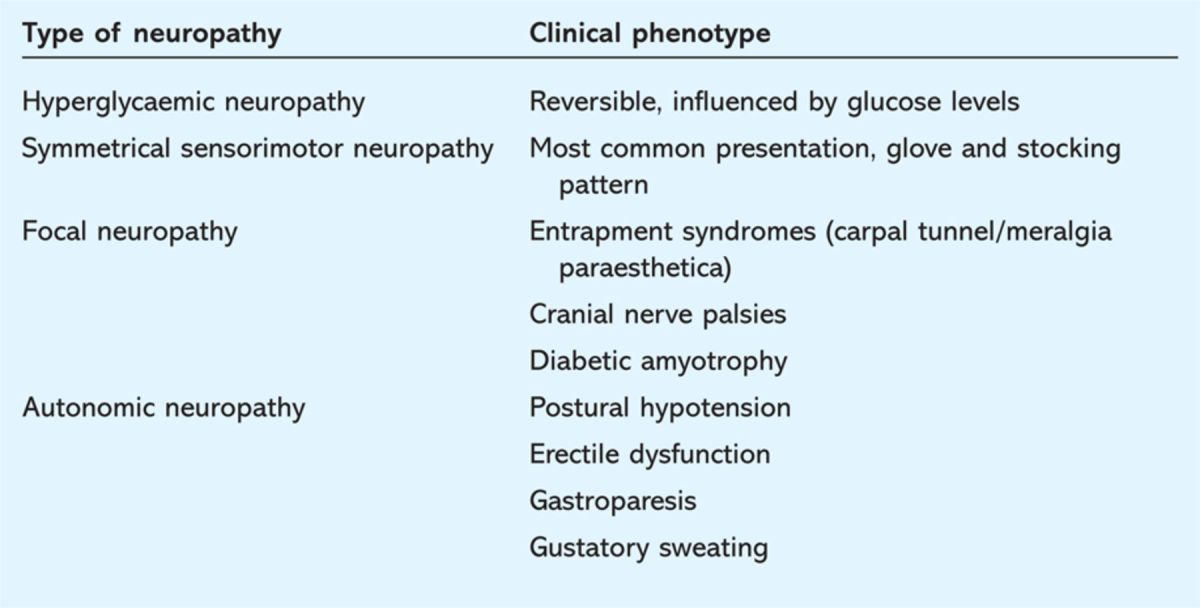

Diabetic neuropathy refers to a spectrum of various neurological disorders associated with diabetes. Rarely, hyperglycaemia can induce an acute neuropathy that is reversible when glycaemic control is improved, but neuropathy is usually persistent. The most common form is a distal, symmetrical sensorimotor neuropathy which may be asymptomatic in up to 50%.25 The spectrum can include a wide range of clinical syndromes (Table 2), including cranial nerve palsies, mononeuropathies and autonomic dysfunction. The main sequel of neuropathy is foot deformity, ulceration and Charcot arthropathy. The combination of neuropathy, arteriopathy and infection are the driving factors behind most diabetic foot amputations.

Table 2.

Overview of the clinical spectrum of diabetic neuropathy.

Management

The management of neuropathy is predominantly supportive. Good glycaemic control can reduce its progression. However, once neuropathy has been established glycaemic control has little influence in controlling pain which is the main symptom. Simple analgesics suffice in mild cases of painful neuropathy, but opiates may be required in more severe cases. Amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin and pregabalin all have evidence of being superior to placebo.25 Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline are first-line agents but pregabalin is particularly useful as therapeutic benefits are seen early. Clinicians need to have empathy with a holistic approach when dealing with these patients and often high doses of analgesics are needed. Patients with neuropathy need to be told of the importance of paying attention to foot care and wearing appropriate footwear as they are at high risk of developing ulcers. Patients also need to have access to podiatry and chiropody services for regular assessment of their feet.

Severe symptoms. Autonomic neuropathy can have devastating effects on patients' lives. Postural hypotension increases the risk of falling. Standard treatments such as fludrocortisone are usually not possible due to coexisting hypertension. Gastroparesis can cause intractable nausea and vomiting in severe cases. Delays in food absorption in mild cases cause severe problems in insulin treated patients where erratic food absorption causes fluctuations in blood glucose levels that are difficult to control with conventional basal bolus regimens. In fact, a large proportion of patients with ‘brittle diabetes’ have some degree of underlying gastroparesis. Mild cases can be managed with prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide, domperidone, erythromycin and dietary modification. More severe cases may require gastric electrical stimulation where implanted electrodes act as a form of gastric pacemaker and stimulate gastric contractions. Unfortunately, this procedure is performed only in specialist centres. Erectile dysfunction affects up to 50% of men with diabetes and is often multifactorial (a combination of neuropathy, small vessel disease, medication and psychological), requiring a holistic approach.

Preventing microvascular disease

Risk factors

The prevention of microvascular disease involves paying attention to aggravating risk factors and implementing screening programmes to improve early detection. Both the UKPDS and DCCT have clearly demonstrated that progression of retinopathy and nephropathy is linked to glycaemic control and that it is crucial that patients maintain HbA1c less than or equal to 6.5% to minimise disease progression. In contrast, the association between glycaemic/BP control and neuropathy progression is more tenuous.

Blood pressure

BP needs to be kept below 140/80 mmHg to prevent microvascular disease, but once this has been established it needs to be more aggressively treated with targets below 125/75 mmHg.26

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)

ACEIs and angiotensin receptor antagonists are first-line agents. Many clinical trials have demonstrated their efficacy in reducing proteinuria and delaying progression of renal failure. In the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study ramipril reduced overt nephropathy by 24%.19 In the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) trial there was a 25% reduction in retinopathy progression and the risk of end-stage renal disease was reduced by 28%.20 Angiotensin blockade with ACEI also has a useful role in preventing retinopathy and reducing its progression by 50%.27However, these agents are potentially teratogenic which needs to be considered when prescribing them to women of reproductive age.

Statins

Statins are useful in reducing the progression of nephropathy. They reduce proteinuria and have modest effects in improving renal function.28 Patients with nephropathy need to have their low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels brought below 2 mmol/l. Statins also have benefits in ameliorating retinopathy in animal models,29,30 though the evidence in clinical trials is less robust. The Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) trial has shown some positive effects of fibrate therapy on retinopathy.31

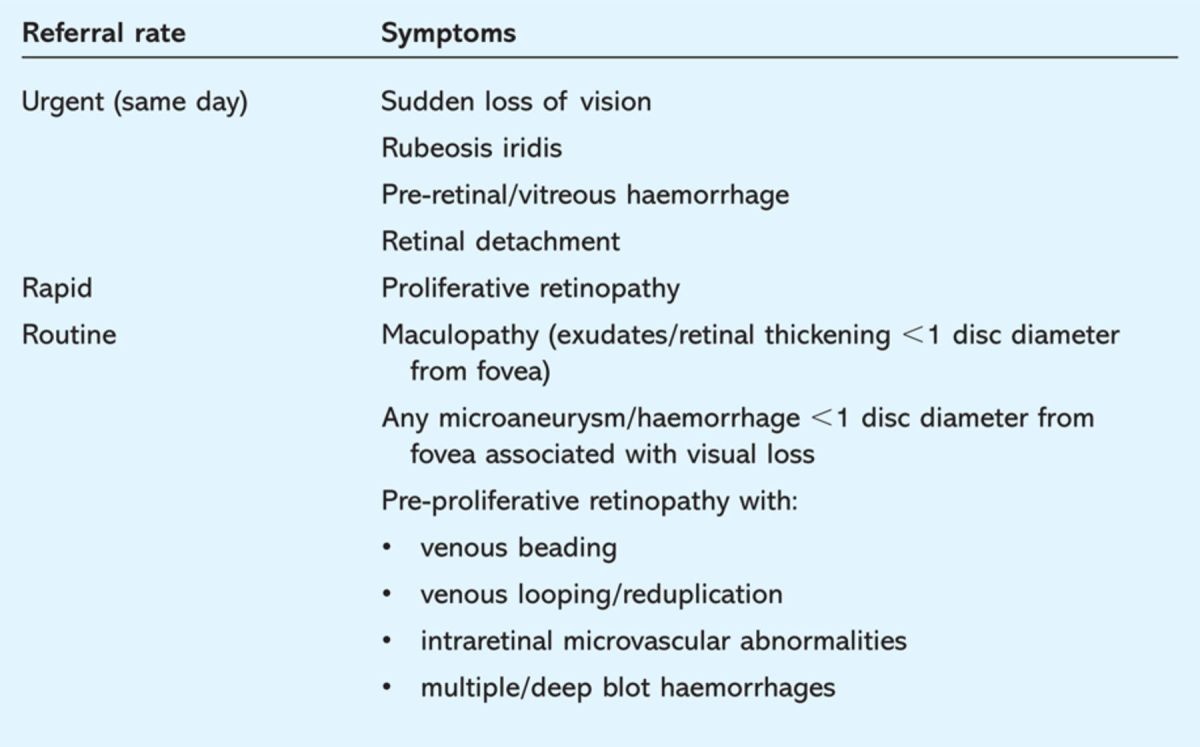

Screening

Microvascular disease needs to be identified early by robust screening methods. Nationwide screening for retinopathy started in the 1990s and has played a central role in reducing diabetes-related visual loss.32 Patients with significant retinopathy need to be referred according to national guidelines (Table 3). Nephropathy can be picked up early by testing for microalbuminuria, and neuropathy detected by detailed foot examination during annual review of the diabetic patient.

Table 3.

Criteria for ophthalmology referral.26

Conclusions

A combined approach of tight glycaemic control, aggressive BP control and cholesterol reduction will help reduce disease progression for both nephropathy and retinopathy, although neuropathy seems to be less affected. Patients with diabetes and their healthcare professionals need to be vigilant and detect microvascular disease at an early stage to avoid potentially devastating complications.

References

- 1.Goh K, Tooke J. Abnormalities of the microvasculature. In: Wass J, Shalet S, Oxford textbook of endocrinology and diabetes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002:1749–55. 10.1001/archneur.65.6.812 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) UK Prospective Diabetes Study. UKPDS Group. Lancet 1998;352:837–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07019-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977–86. 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001;414:813–20. 10.1038/414813a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giunti S, Barit D, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy: role of hypertension. Hypertension 2006;48:519–26. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000240331.32352.0c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rassam S, Patel V, Kohner EM. The effect of experimental hypertension on retinal vascular autoregulation in humans: a mechanism for the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Exp Physiol 1995;80:53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Davis MD, DeMets DL. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. II. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is less thn 30 years. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:520–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahl-Jörgensen K, Brinchmann-Hansen O, Hansen KF, et al. Rapid tightening of blood glucose control leads to transient deterioration of retinopathy in insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: the Oslo study. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:811–5. 10.1136/bmj.290.6471.811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chantelau E, Kohner EM. Why some cases of retinopathy worsen when diabetic control improves. BMJ 1997;315:1105–6. 10.1136/bmj.315.7116.1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Ophthalmologists Guideline for diabetic retinopathy. Executive summary. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Axer-Siegel R, Hod M, Fink-Cohen S, et al. Diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy. Ophthalmology 1996;103:1815–9. 10.1016/S1056-8727(96)00003-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein BE, Moss SE, Klein R. Effect of pregnancy on progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 1990;13:34–40. 10.2337/diacare.13.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health Diabetes in pregnancy: management of diabetes and its complications from pre-conception to the postnatal period. London: NCCWCH, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Early photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy, ETDRS report number 9 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology 1991;98:766–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams G, Pickup JC. The handbook of diabetes, 3rd edn. Oxford Blackwell Publishing, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gnudi L, Gruden G, Viberti GC. Pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. In: Pickup JC, Williams G, Textbook of diabetes, 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003;521–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritz E, Orth SR. Nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1127–33. 10.1056/NEJM199910073411506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson JC, Adler S, Burkart JM, et al. Blood pressure control, proteinuria, and the progression of renal disease. The modification of diet in renal disease study. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:754–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study. Lancet 2000;355:253–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)12323-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001;345:861–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group N Engl J Med 19933291456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mogensen CE, Neldam S, Tikkanen I, et al. Randomised controlled trial of dual blockade of renin-angiotensin system in patients with hypertension, microalbuminuria, and non-insulin dependent diabetes: the candesartan and lisinopril microalbuminuria (CALM) study. BMJ 2000;321:1440–4. 10.1136/bmj.321.7274.1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ONTARGET Investigators. Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1547–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakris GL, Ruilope L, Locatelli F, et al. Treatment of microalbuminuria in hypertensive subjects with elevated cardiovascular risk: results of the IMPROVE trial. Kidney Int 2007;72:879–85. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boulton AJ, Vinik AI, Arezzo JC, et al. Diabetic neuropathies: a statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2005;28:956–62. 10.2337/diacare.28.4.956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions Type 2 diabetes: national clinical guideline for management in primary and secondary care (update). London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaturvedi N, Sjolie AK, Stephenson JM, et al. Effect of lisinopril on progression of retinopathy in normotensive people with type 1 diabetes. The EUCLID Study Group. EURODIAB Controlled Trial of Lisinopril in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. Lancet 1998;351:28–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandhu S, Wiebe N, Fried LF, Tonelli M. Statins for improving renal outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17:2006–16. 10.1681/ASN.2006010012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medina RJ, O'Neill CL, Devine A, Gardiner TA, Stitt AW. The pleiotropic effects of simvastatin on retinal microvascular endothelium has important implications for ischaemic retinopathies. PLoS One 2008;3:e2584. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawahara S, Hata Y, Kita T, et al. Potent inhibition of cicatricial contraction in proliferative vitreoretinal disease by statins. Diabetes 2008;57:2784–93. 10.2337/db08-0302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keech AC, Mitchell P, Summanen PA, et al. Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:1687–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61607-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachmann MO, Nelson SJ. Impact of diabetic retinopathy screening on a British district population: case detection and blindness prevention in an evidence-based model. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:45–52. 10.1136/jech.52.1.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]