Abstract

The current proposals to update the European Union (EU) directive on professional qualifications will have potentially important implications for health professions. Yet those discussing it will struggle to find basic information on key issues such as licensing and registration of physicians in different countries. A survey was conducted among national experts in 14 EU member states, supplemented by literature and independent expert review. The questionnaire covered five components of licensing and registration: (1) definitions, (2) regulatory basis, (3) governance, (4) the process of registration and (5) flow and quantity of applications. We identify seven areas of concern: (1) the meaning of terminology, which is inconsistent; (2) the role of language assessments and the responsibility for them; (3) whether approval to practise should be lifelong or time limited, subject to periodic assessment; (4) the need for improved systems to identify those deemed no longer fit to practise in one member state; (5) the complexity of processes for graduates from non-EU/European Economic Area (EAA) countries; (6) public access to registers; and (7) transparency of systems of governance. The systems of licensing and registration of doctors in Europe have developed within specific national contexts and vary widely. This creates inevitable problems in the context of free movement of professionals and increasing mobility.

KEYWORDS : Registration, licensing, revalidation, directive on professional qualifications, professional mobility

Introduction

Doctors have long had the right to practise throughout the European Union (EU). EU legislation enacted in 1975 (Council directives 75/362/EEC and 75/363/EEC) and its subsequent revisions set out the core requirements for registration as a medical practitioner.1–3 These underpin the assumption that anyone licensed as a medical practitioner in any EU member state is qualified to practise anywhere else, something that derives from the fundamental freedoms of movement enshrined in European treaties. Yet, in some countries, there have been concerns that the system is not working. First, the core training requirements are defined in terms of hours of study, rather than the acquisition of defined competences, now seen in many countries as the mark of completion of training. Second, the concept of lifelong qualification is being challenged in some countries by requirements to demonstrate continuing competence at points throughout one's working career. Third, there have been some high-profile cases of failings by doctors working outside the country in which they obtained their qualification.

The most recent directive, which came into force in 2007, is being revised in response to these concerns. A draft text was proposed by the European Commission in July 2013 with proposals for a voluntary European ‘professional card’, an alert mechanism for malpractice or fraudulent diplomas, and the ability of competent authorities to assess language skills. On 9 October 2013 the text was accepted by the European Parliament and is expected to be approved formally by member states in the Council of Ministers. Although these provisions still assume that registration and licensing systems are comparable across the EU, even after four decades of experience with free movement of doctors it remains remarkably difficult to discover what those systems are. It is timely to address this gap in the literature.

Methods

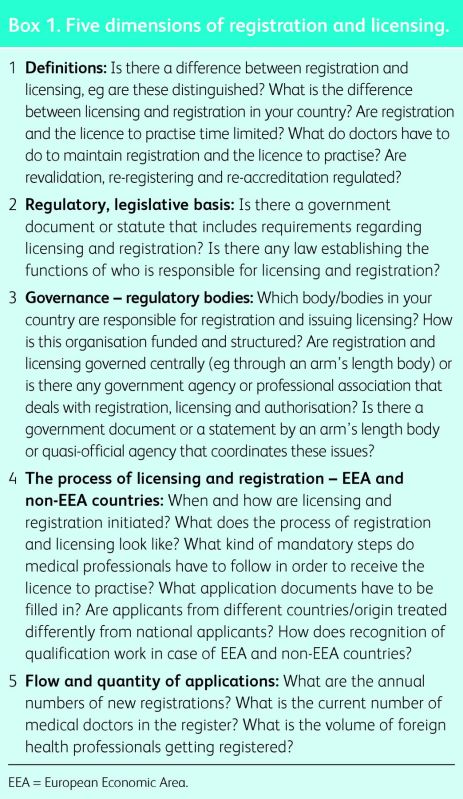

Key informants were identified in 14 EU member states: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, Romania, Slovenia, Spain and the UK. Each was sent a questionnaire covering five key components of licensing and registration:

definitions

regulatory basis

governance

the process of registration

the flow and quantity of applications for movement by doctors (Box 1).

This was supplemented by reviews of peer-reviewed and grey literature.

The questionnaire was developed in consultation with the UK's General Medical Council (GMC). It was piloted among collaborating researchers in 11 of the countries to ensure clarity of terminology. Data collection took place between September 2010 and October 2012. In October 2013, the paper was sent to at least one expert in each country to check the validity and to make sure that the data took account of recent developments. Inconsistencies were resolved, as far as possible, by triangulation with data from different sources.

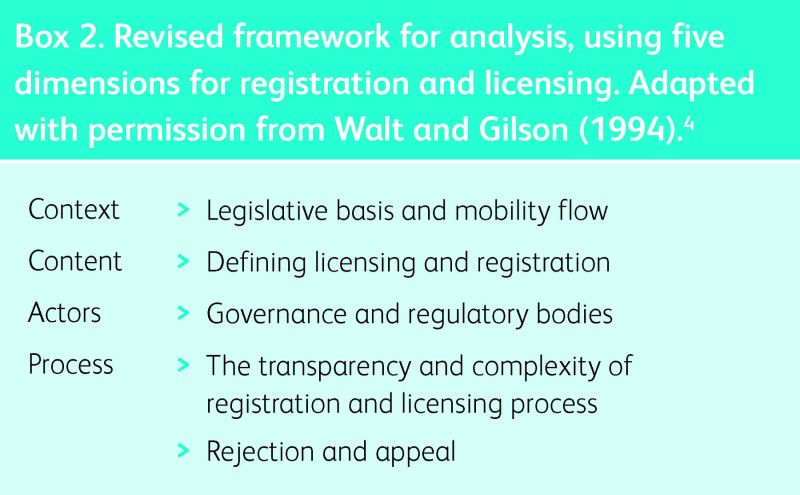

The analytical framework

The analytical framework builds on the model of policy analysis developed by Walt and Gilson.4 This comprises four elements: the content of the policy, the actors involved, the processes by which policy is formulated and the contextual factors that help to frame the policy. The adaptation of this framework to medical registration and licensing is shown in Box 2.

Box 1. Five dimensions of registration and licensing.

Results

Context

Legislative basis and mobility flow

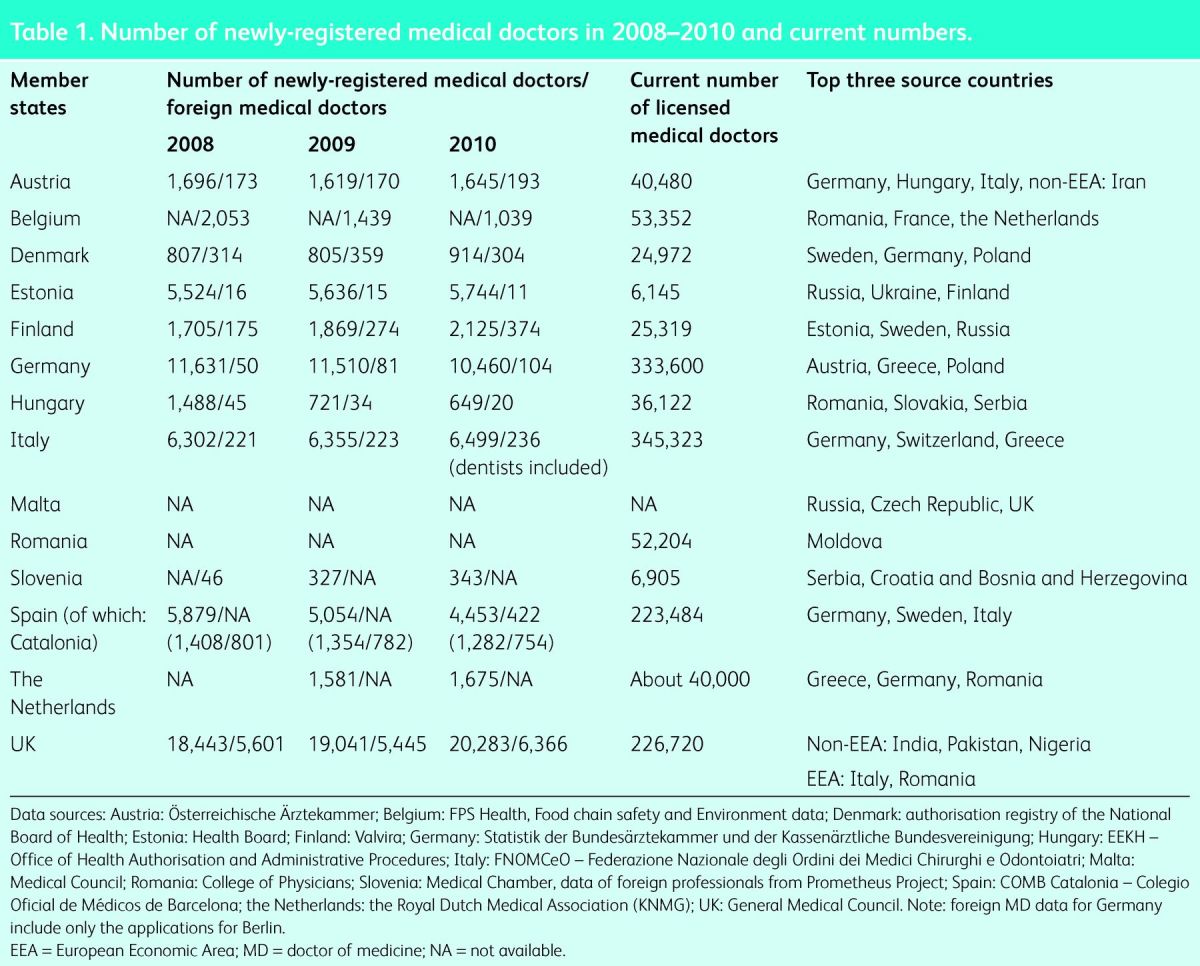

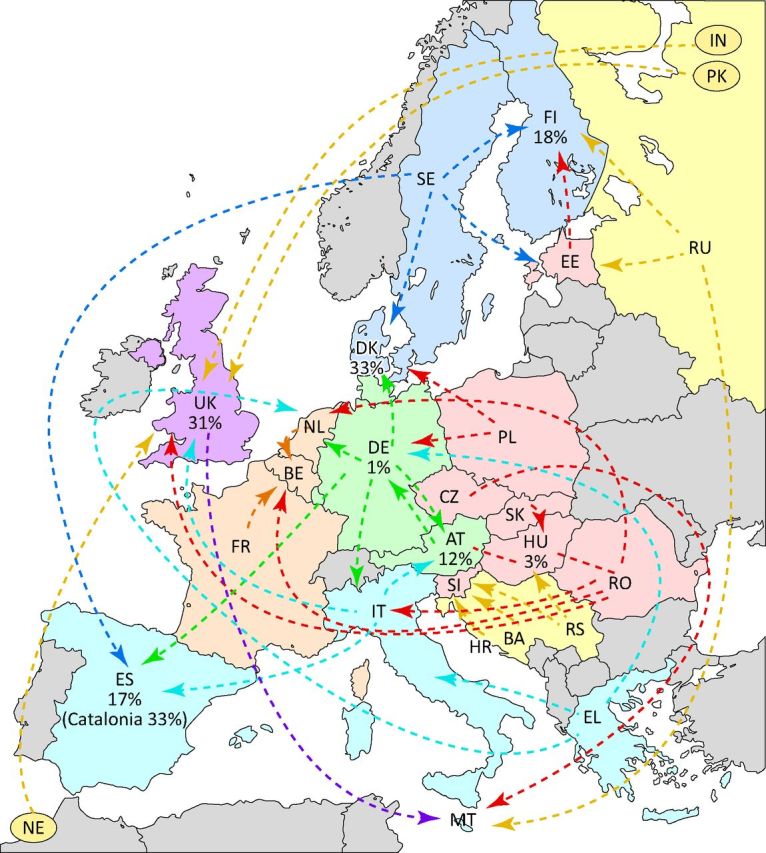

The main contextual factors are the relevant EU legislation and the factors influencing professional mobility. Professional mobility within the EU has been discussed at length elsewhere.5 In brief, it arises from a combination of push-and-pull factors including differentials in salaries and opportunities for professional development. In general, movement has been from countries offering lower salaries and fewer opportunities to those offering more. Table 1 shows the numbers of newly registered medical doctors and newly registered medical doctors with foreign training in 2008–10 (or latest available year). Patterns of mobility are shown in Fig 1. These highlight the role of cultural and linguistic similarities and longstanding historical ties in determining patterns of mobility.5 The UK and Ireland benefit from the widespread use of English, making the UK the most popular recipient country for doctors. These links also underlie the scale of movement between Austria and Germany, Slovenia and other former Yugoslav countries, Belgium and France, and Belgium and the Netherlands.

Table 1.

Number of newly-registered medical doctors in 2008–2010 and current numbers.

Fig 1.

Mobility of medical doctors. AT = Austria; BA = Bosnia and Herzegovina; BE = Belgium; CZ = Czech Republic; DE = Germany; DK = Denmark; EE = Estonia; EL = Greece; ES = Spain; FR = France; FI = Finland; HU = Hungary; HR = Croatia; IN = India; IT = Italy; MT = Malta; NE = Nigeria; NL = the Netherlands; PK = Pakistan; PO = Poland; RO = Romania; RS = Republic of Serbia; RU = Russia; SE = Sweden; SI = Slovenia; SK = Slovakia; UK = United Kingdom.

Content

Defining licensing and registration

Licensing and registration are designed to ensure that professionals achieve minimum standards of competence, although the terminology is not always used consistently,6,7 in part reflecting definitional ambiguity. Licensing has been defined as ‘the process of authorization or authenticating the right of a physician to engage in medical practice, its monitoring (regulation) and renewal or extension’.8 The same source defines registration as ‘all the processes associated with the issuing of licences/authorisations to practise medicine and ensuring that the professional activities carried out under this authority maintain the professional standards on which it is based’. It is apparent that these definitions could be improved to provide greater clarity. Thus, registration can be considered to be the act of placing an individual on a list of medical practitioners by virtue of having obtained a qualification and possibly a licence (neither of which has been forfeited for any reason), whereas licensing means that that person has been assessed as fit to practise currently. These two may be combined (whereby being placed on the register confers a right to practise) or separate, when they can take place simultaneously (and in some cases automatically) or consecutively (ie only those on a register can be licensed, or vice versa – Table 2).

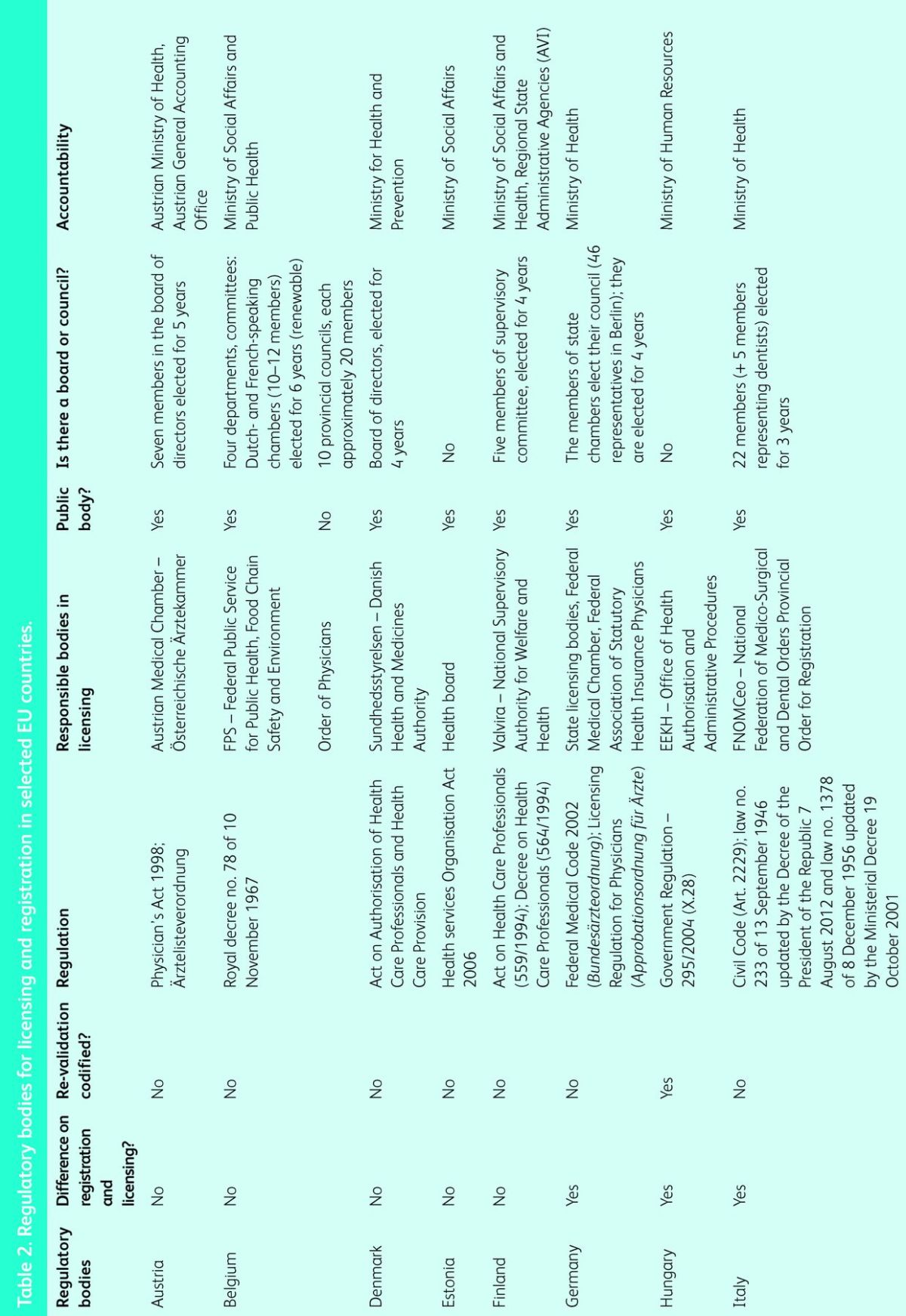

Table 2.

Regulatory bodies for licensing and registration in selected EU countries.

There are many variants, with the words used illustrating the terminological problems. In Slovenia and Hungary, although graduation entitles the individual to registration, the licensing process is separate and time limited. Both processes (registration and licensing) must be completed to practise. The UK has recently followed suit. In contrast, in Romania the licence is issued on completion of training whereas registration confers the right to practise. In Belgium a licence (so-called ‘visa’) is issued automatically after graduation. However, doctors must then register on the ‘cadastre’ to be able to practise. In Germany, health authorities at regional (Land) level award lifelong licences that recognise the fitness of doctors to practise but they must then register with the Chamber of Physicians in the Land in which they intend to work (or where they live if they do not intend to work). If they move to a different Land, they keep their licence but change their registration.

In some countries medical professionals can be registered and/or licensed as general practitioners/medical doctors/physicians and as medical specialists regardless of their status (active/inactive, eg Hungary, Germany). Independent practice requires having the status of being registered and/or licensed and authorised for fitness to practise. Provisional registration or licensing, as currently applies to doctors in the UK during their first year of supervised practice after graduation, is rare but also found in Spain and Germany (Berufserlaubnis); in all cases it is temporary, while awaiting completion of the registration process.

Box 2. Revised framework for analysis, using five dimensions for registration and licensing. Adapted with permission from Walt and Gilson (1994).4

Actors

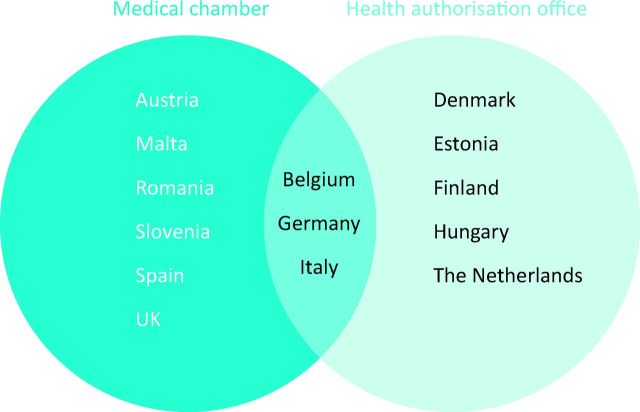

Governance and regulatory bodies

Regulation of the medical profession is undertaken by a diverse array of national bodies, many of which combine this role with others, such as professional standards or representation in negotiations on terms and conditions (Table 2). They vary from government ministries to self-regulating professional bodies, with varying degrees of statutory regulation. Medical chambers play a major role in the registration and licensing process in some countries (Fig 2). In federal countries the process may be devolved to regions, as in Spain and Germany.

Fig 2.

Responsible bodies for registration and licensing. Note: the countries where registration and licensing are conducted by health authorisation offices also have medical chambers, but the chamber is not responsible for medical licensure. Health authorisation offices are often attached to public bodies such as the Ministry of Health.

In Malta and Romania registration and licensing are undertaken by national medical associations. Other public institutions govern the licensing and registration in the UK, Denmark, Estonia, Finland and Hungary. In the UK, the GMC maintains the register of doctors and issues licences, normally for 5 years. The UK is the only country with a registration body that includes lay members.

Process

The transparency and complexity of the registration and licensing process

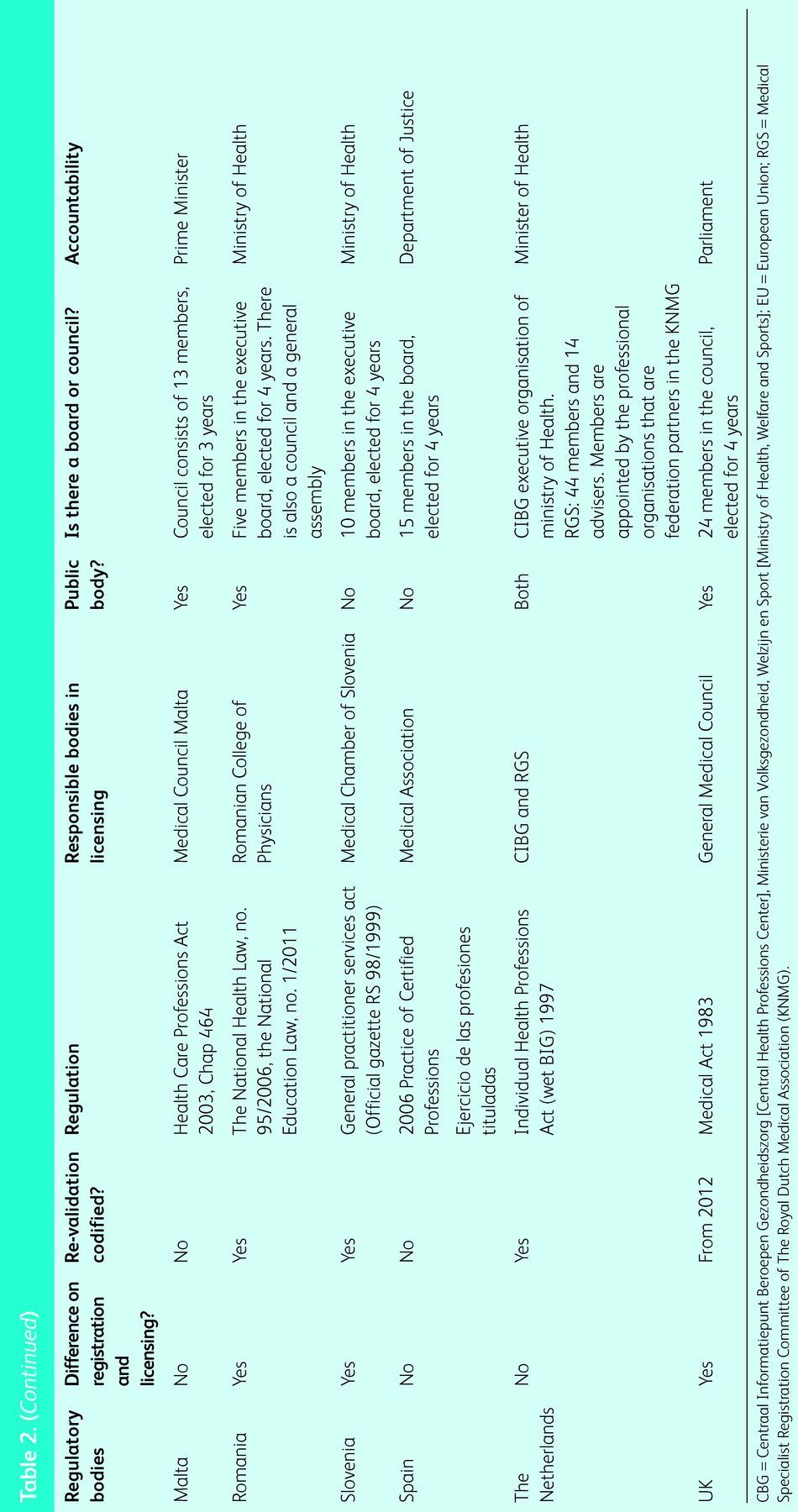

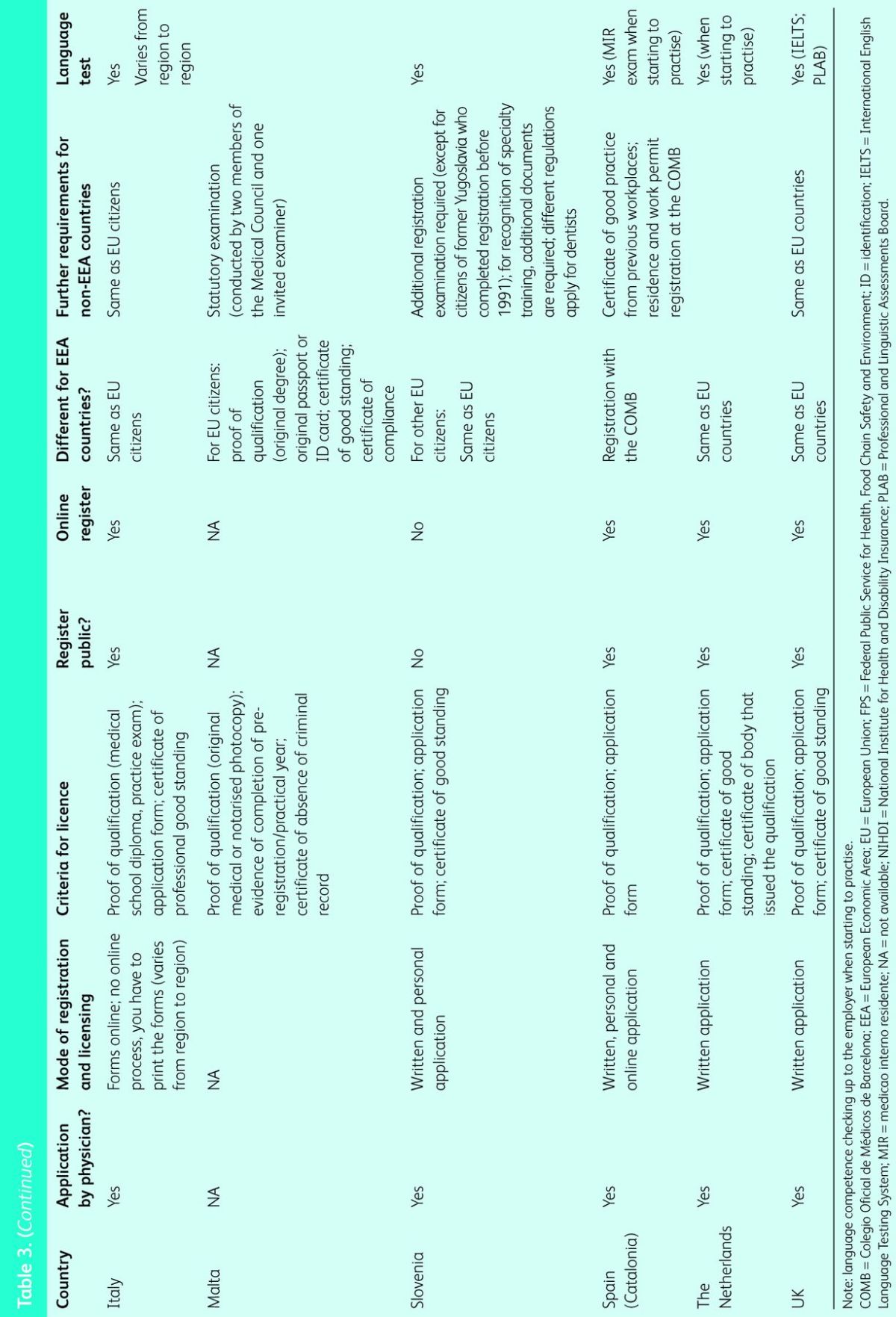

In all the countries studied, doctors must apply to be registered, except in Belgium and Hungary where it is done on their behalf by, respectively, the governmental body and the universities in which they were trained. Thus, obtaining a medical degree does not necessarily lead to registration and/or licence to practise (Table 3). This is important because registration processes differ considerably among countries and may represent significant hurdles, especially for doctors graduating from other countries.9

Table 3.

Registration/licensing process in selected EU countries.

In all countries, application for registration is in writing, but some also require the individual to appear in person (eg Austria), whereas others offer the option of online registration (eg Catalonia).

The criteria for registration vary: only in Hungary and Belgium is the registration issued automatically on obtaining a medical degree. Even in these cases, however, the ‘minimum syndical’ is needed before licensing, which usually consists of proof of qualification, an application form and a certificate of good standing. Others require further documentation such as proof of practical experience (eg Malta) or specialised training (eg Belgium). Although registration processes are the same for national and other EU graduates, some countries have expedited registration processes for citizens from specific countries (Table 3). For example, Slovenia has a slightly different procedure for citizens from former Yugoslavia who qualified before 1991,10,11 and Denmark for citizens from Nordic countries with which there are bilateral agreements.8 For citizens from non-EU countries, additional examinations are usually required (eg Hungary, Finland, Malta, Germany, Denmark and the UK), and for some further documentation is needed.

Graduates from outside the EU must demonstrate competence in appropriate languages, although this is not a requirement for registration by graduates of other EU countries. However, employers will normally wish to ensure that those they employ have the language skills necessary to do the job. For example, the English Department of Health said that it would require all doctors employed in the NHS to be competent in English from April 2013, but it is not clear how it might do this amidst the extensive legal confusion created by its recent reforms. There is, however, a loophole for those seeking to establish themselves in independent practice. Language requirements may, however, represent significant practical hurdles in countries with languages that are not widely spoken. Thus, in Finland, patients have the right to communicate with a health professional in either Swedish or Finnish, the two official languages,12,13 and doctors from non-EU/EEA (European Economic Area) countries are required to learn Finnish to be granted a licence to practise.13

The stringency of the processes involved in registration varies. However, even in the absence of harmonisation, we could find no evidence of systematic discrimination against non-nationals. Rather, for historical reasons, in some countries bilateral agreements allow for a more favourable treatment of citizens from some countries than from others.

In most countries, medical registers are publicly accessible and can be accessed online. However, in Austria and Germany the Medical Chamber and the Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) [Federal Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians], respectively, act as the ‘custodians’ of the registers, with only partial access to the public. Nor are registers available to the public in Belgium or Denmark.

Rejection and appeal

The data supplied by key informants suggest that it is rare for an application to be rejected, with fewer than five cases in any country each year being rejected. Reasons include non-recognised medical qualifications (Slovenia) and a few cases of falsified documents (Finland). Doctors are entitled to appeal against rejections. For example, in Austria, appeals can be made to the higher administrative court (Verwaltungsgerichtshof) or the constitutional court (Verfassungsgerichtshof). In Italy, appeals against disciplinary decisions of the order are possible at the central committee of FNOMCeo (National Federation of Physicians and Dentists), then to the central commission for the practising health professions (based in the Ministry of Health), and ultimately in the courts.

Discussion

This study reveals just how complex the systems of licensing and registration are within the EU, with different interpretations of even the basic terminology. The challenges facing doctors moving between countries and those responsible for their registration and licensing are apparent.14 However, concerns have been voiced in some member states that any simplification of recognition procedures could undermine patient safety.3 A particular concern is the need to balance freedom of movement with language competence, especially given the need for complex terminology in medicine and the nuances of patient communication. However, there is an argument that this issue should be addressed by recruitment procedures, not registration, because there will be some situations, such as laboratory medicine, where fluency in a language other than English may be of less importance. Another concern relates to the lack of transparency, with some countries refusing access to lists of registered professionals, and problems in ensuring that professionals barred in one country do not move across borders to practise somewhere else, a concern that could be addressed with an alert system for health professionals.1

Some patterns emerge from our data. Hungary and Germany have more complex bureaucratic pathways, whereas Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Malta, Slovenia and the Netherlands have much simpler ones. Belgium, Italy, Spain (Catalonia), as well as Romania and the UK, occupy intermediate positions.

Registers are important tools in workforce planning, especially given increased professional mobility which, in some countries, is leading to severe shortages of doctors in particular specialties and settings.14,15 However, the data must be accurate and available in a timely manner. It is not clear that this is always the case.

This survey has enabled the authors to identify seven areas where action is needed. The first is to agree on the terminology and, especially, to ensure consistent usage of the words registration and licensing. Second, there is no argument that a doctor must be able to communicate in a work setting, although what this means in practice may vary. Thus, there is a need to have a full and frank debate about language competence, clarifying who is responsible for assessing it and, specifically, the roles of the registration or licensing authorities or the employers, and the oversight of those in independent practice. The third is to reach agreement on at least the principle of whether registration or licensing should be time limited and what processes should be used to renew this status. There is widespread agreement on the importance of engaging in continuing professional development but not about any sanction for failing to undertake it. In practice, only very few member states have revalidation mechanisms (see Table 2) and those that exist, such as that in the UK, are unevaluated and there is some scepticism that they will be effective.16 Fourth, and related to this point, there is a need for improved systems to identify those who are deemed no longer fit to practise in one member state, for whatever reason. Fifth there may be scope, in some countries, to simplify the rules for graduates from non-EU/EEA countries, because these can create considerable additional work for the competent authorities and create undue barriers to mobility.13 Sixth, it seems remarkable that, in the 21st century, some registers are not open to the public. Finally, in many member states there is a need for much greater clarity about systems of governance and, in particular, who is responsible for what. This seems to be a particular problem in some federal countries (eg Germany and Italy).

In summary, the systems of licensing and registration of doctors within the EU/EEA are extremely complex and confusing. Measures to bring clarity to them are long overdue.

Acknowledgements

We thank all questionnaire respondents who took time to generously provide us with the requested information. We particularly wish to thank all the institutions participating in the study: LSE Health (the UK), London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (the UK), European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (Belgium), Observatorie Social Europeé (Belgium), Technische Universität Berlin (Germany), Maastricht University (the Netherlands), European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research (Austria), Institute of Public Health of the Republic of Slovenia (Slovenia), Universitat de Barcelona (Spain), PRAXIS Centre for Policy Studies (Estonia), National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (Finland) and Semmelweis University, Health Services Management Training Centre (Hungary). We would like to thank the independent country reviewers: Dr Christian Claus Schiller (Austria), Carl Steylaerts (Belgium), Tiia Raudma (Estonia), Reijo Ailasmaa (Finland), Dimitra Pantelli (Germany), Nándor Rikker (Hungary), Sara Rigon, Harris Lygidakis (Italy), Sietse Wieringa, Ronald Batenburg (Netherlands), Janko Kernisk, Eva Turk (Slovenia), Meritxell Sole (Spain), Roar Maagaard (Denmark), Raluca Zoitanu (Romania), Luisa Petigrew and Nigel Sparrow (the UK). We would also like to thank Katrin Gasior (Austria) for her assistance in producing graphs.

References

- 1.European Commission Modernising the professional qualifications directive. Brussels: European Commission, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.General Medical Council GMC position paper. Draft directive on the application of patients’ rights in cross border healthcare in Europe. London: GMC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal College of Physicians Review of the professional qualifications directive: Mobility of healthcare professionals. London: RCP, 2011. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/rcp_response_to_house_of_lords_june_17_2011.pdf [Accessed 12 March 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan 1994;9:353–70. 10.1093/heapol/9.4.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wismar M, Maier CB, Glinos IA, Dussault G, Figueras J. (eds). Health professional mobility and health systems. Evidence from 17 European countries. Brussels: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legido-Quigley H, McKee M, Walshe K, et al. How can quality of health care be safeguarded across the European Union? BMJ 2008;336:920–3. 10.1136/bmj.39538.584190.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenwood MJ, Beasley-Greenwood M. Medical licensure and credentialing. In: Norman SM. (ed), Principles of addictions and the law. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 2010:55–74. 10.1016/B978-0-12-496736-6.00004-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe A, García-Barbero M. Regulation and licensing of physicians in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galan A. Health worker migration in selected CEE countries: Romania. In: Wiscow C. (ed), Health worker migration flows in Europe: overview and case studies in selected CEE countries – Romania, Czech Republic, Serbia and Croatia. Geneva: International Labour Office, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albreht T, Pribakovic Brinovec R, Stalc J. Cross-border care in the south: Slovenia, Austria and Italy. In: Rosenmöller M, McKee M, Baeten R. (eds), Patient mobility in the European union: learning from experience. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2006:9–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albreht T. Addressing shortages: Slovenia's reliance on foreign health professionals, current developments and policy responses. In: Wismar M, Maier CB, Glinos IA, Dussault G, Figueras J. (eds), Health professional mobility and health -systems : evidence from 17 European countries. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2011:511–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jesse M, Kruuda R. Cross-border care in the north: Estonia, Finland and Latvia. In: Rosenmöller M, McKee M, Baeten R. (eds), Patient mobility in the European union: learning from experience. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2006:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuusio H, Koivusalo M, Elovainio M. et al. Changing context and priorities in recruitment and employment: Finland balances inflows and outflows of health professionals. In: Wismar M, Maier CB, Glinos IA, Dussault G, Figueras J. (ed.), Health professional mobility and health systems: evidence from 17 European countries. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2011:163–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Commission Towards a job-rich recovery. Commission staff working document on an action plan for the EU health workforce, accompanying the document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Strasbourg: European Commission, 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/health_consumer/docs/swd_ap_eu_healthcare_workforce_en.pdf [Accessed 29 April 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jesilow P, Ohlander J. The impact of the national practitioner data bank on licensing actions by state medical licensing boards. J Health Human Services Admin 2010;33:94–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkes N. Revalidation seems to add little to the current appraisal process. BMJ 2012;345:e7375. 10.1136/bmj.e7375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]