Abstract

Acute ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) results from complete obstruction to coronary artery blood flow accompanied by the appearance of ST-segment-elevation on the electrocardiogram. Emergency treatment is required to restore coronary perfusion, thereby limiting the extent of damage to the myocardium and the likelihood of early death or future heart failure. This concise guideline summarises key recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guideline on acute management of STEMI (CG167), of relevance to all healthcare professionals involved. Guidance is presented on choice of reperfusion strategies, procedural aspects, use of additional drugs before and alongside reperfusion therapies, and treatment of patients who are unconscious or in cardiogenic shock.

KEYWORDS: STEMI, myocardial infarction, primary percutaneous coronary intervention, reperfusion, myocardial ischaemia, thrombolysis, fibrinolysis

Introduction

ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is at one end of the spectrum of related acute coronary syndromes. The common pathophysiology involves either erosion or sudden rupture of an atheromatous plaque within the coronary artery wall, with resulting intraluminal thrombosis, complete obstruction to blood flow and the appearance of ST-segment-elevation on the electrocardiogram. Without intervention, the consequent myocardial cell death worsens progressively with time.

STEMI typically presents with acute chest pain, although symptoms may include sweating, nausea and breathlessness, and may be atypical, particularly in women and people with diabetes.

Epidemiology of STEMI

The incidence of STEMI has been declining over the past 20 years1,2 and varies between regions,3 but currently averages around 500 hospitalised episodes per million people annually in the UK.4 Ventricular arrhythmias may occur early after the onset of an acute coronary syndrome and may cause sudden cardiac death in around one-third of people with STEMI before access to emergency medical care.5,6 The true incidence of STEMI may therefore be much higher than the reported hospitalised average.

Certain groups (eg women and those from ethnic minorities) may delay calling for medical help, increasing the risk of cardiac arrest and greater myocardial damage. Nevertheless, over the past 30 years in-hospital mortality following acute coronary syndromes has fallen from around 20% to nearer 5%, at least in part due to earlier access to effective treatment.7 Adoption of evidence-based treatment in Sweden was associated with a decrease in mortality sustained over 12 years.8

The importance of ‘time’ and reperfusion therapy

More than 30 years ago, coronary angiography was used to demonstrate complete coronary occlusion as the cause of STEMI, 9 and animal models suggest that nearly half of potentially salvageable myocardium is lost within one hour of acute occlusion.10 Apart from resuscitation from any cardiac arrest, the highest priority is therefore to restore adequate coronary blood flow as quickly as possible.

During the 1980s and 90s, randomised clinical trials established the effectiveness of fibrinolytic drugs in limiting myocardial damage by restoring coronary blood flow following coronary thrombosis.11 The UK introduced a comprehensive system for delivering fibrinolysis in 2000, whereby an increasing proportion of fibrinolysis was delivered by paramedics before hospital admission.12 Fibrinolysis, however, has important limitations: it is contraindicated in some (eg because of bleeding complications), it fails to achieve adequate coronary reperfusion in around 20–30%, and in a few (1%) it causes haemorrhagic stroke. Attention therefore turned to mechanical techniques (coronary angioplasty, thrombus extraction catheters and stenting), collectively termed primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI).

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has accredited the process used by the Royal College of Physicians to produce the concise clinical guidelines published in Clinical Medicine with effect February 2010 to March 2018 (abstracted guidance) and July 2013 to July 2018 (de novo guidance). More information on accreditation can be viewed at: www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/accreditation.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention

The National Infarct Angioplasty Project (2008) in England concluded subsequently that PPCI as the principal coronary reperfusion strategy was both feasible and cost effective, and that it should become the treatment of choice for STEMI, provided it can be delivered ‘in a timely fashion’.13

Undue delay between the time when fibrinolysis could be given and PPCI is delivered may negate the outcome benefits. A PPCI strategy therefore requires emergency access to a cardiac catheter laboratory and specialist staff at all times. If, however, a patient with STEMI presents far from a PPCI centre either in distance or travel time, fibrinolysis may then be the preferred strategy.

Given the complexity of delivering PPCI, optimal service configuration requires a single reperfusion pathway for people with STEMI in each locality. It should work consistently and be reproducible for all, both within and outside normal working hours. Inconsistency on the basis of time of presentation or availability of staff or facilities at the admitting hospital is unacceptable. The prime determinant of clinical benefit following PPCI is the degree of myocardial salvage (a function of timeliness, effectiveness and maintenance of coronary reperfusion).

If combinations of potent antithrombotic agents are used, bleeding complications are also important in both morbidity and mortality. Multi-professional team working is essential. After successful acute treatment, secondary prevention, lifestyle modification and cardiac rehabilitation (beginning in the hospital period) are required, as with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (see related National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance14–16).

Scope and purpose

This concise guideline summarises key recommendations detailed in the full NICE guideline (CG167).17 It is intended for use by all healthcare professionals who encounter patients with STEMI and focuses on acute management, including choice of reperfusion strategies, procedural aspects of the recommended interventions, use of additional drugs before and alongside reperfusion therapies, treatment of those unconscious following out of hospital cardiac arrest, and management of cardiogenic shock.

A summary of the overall care pathway is also included to provide context. Recommendations on procedural aspects specifically aimed at PPCI operators or trainees are in the full NICE guideline.17

Recommendations

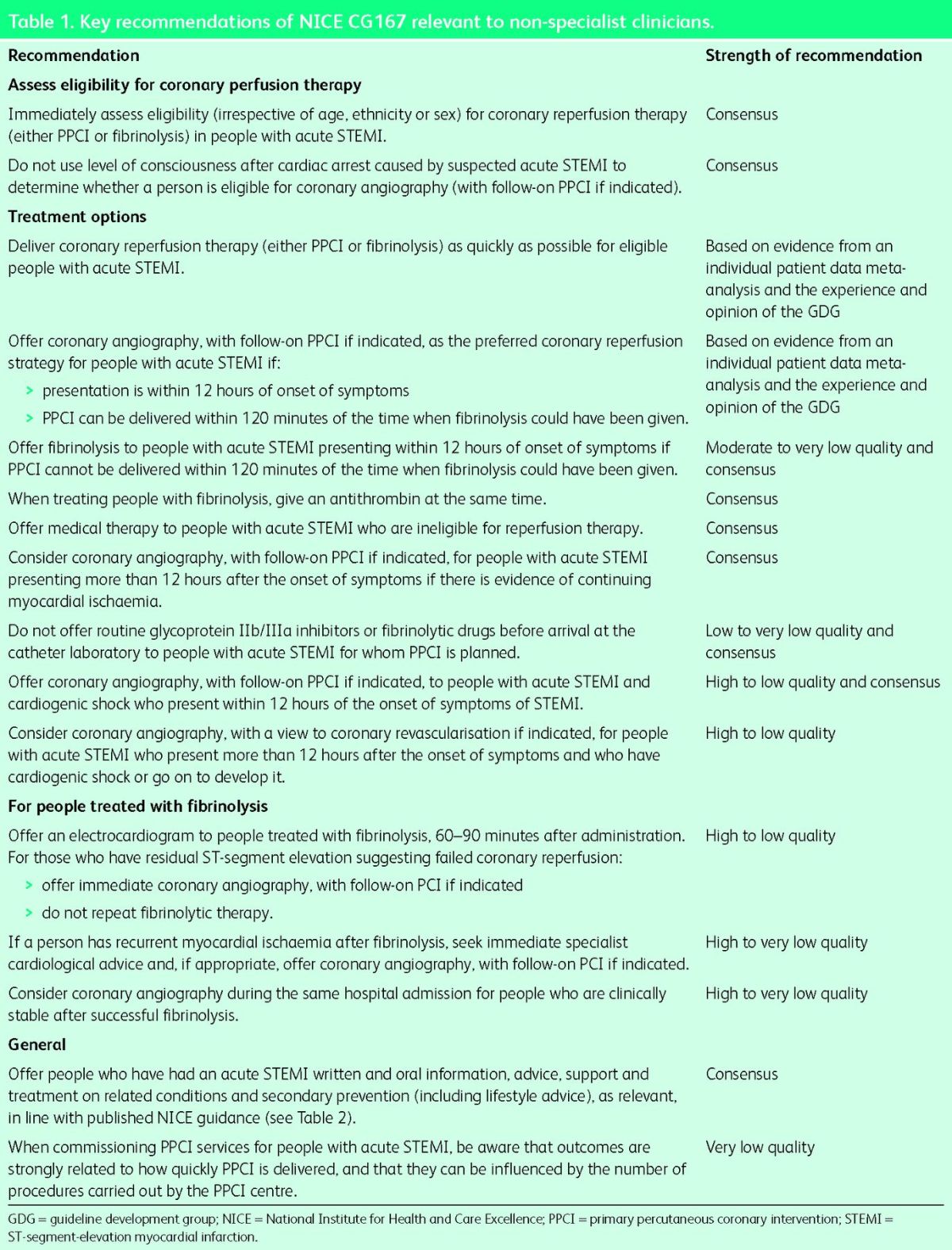

There are 20 recommendations in CG167, incorporating two from related NICE technology appraisals. Table 1 highlights those of particular relevance to non-specialist clinicians.

Table 1.

Key recommendations of NICE CG167 relevant to non-specialist clinicians.

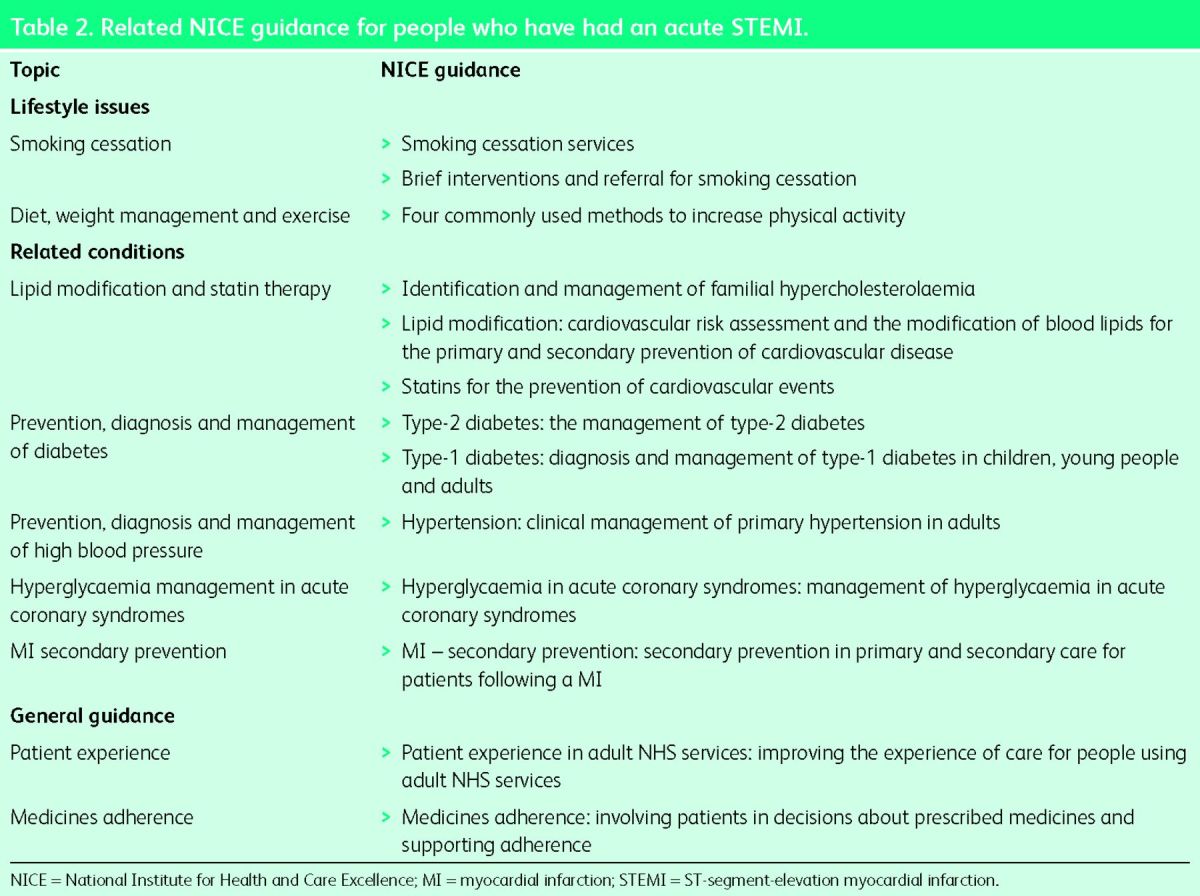

Table 2.

Related NICE guidance for people who have had an acute STEMI.

The issue of ‘timeliness’ is a key element of the CG167 recommendations. People developing symptoms of STEMI may call the emergency services or self-present to an emergency department. STEMI may also occur in patients already in hospital for other reasons, such as surgical operations. Effective management requires immediate assessment of eligibility for, and effective delivery of, reperfusion therapy. Based on the evidence, the guideline recommends PPCI as the preferred reperfusion strategy provided it can be delivered within two hours of the time that fibrinolysis could have been given.

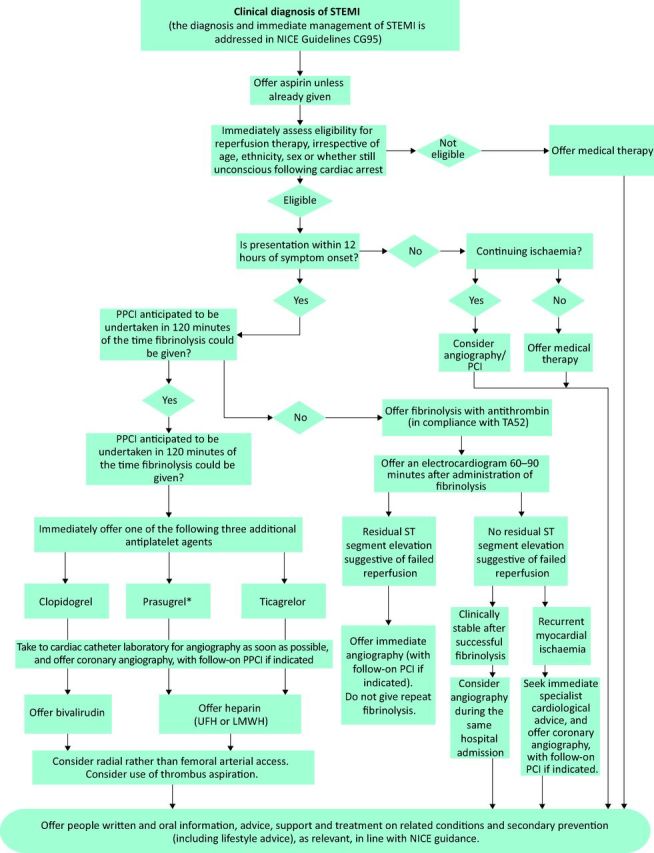

With respect to patients with STEMI who remain unconscious after resuscitation from cardiac arrest, or those with cardiogenic shock, both groups should be considered for PPCI irrespective of their conscious state or degree of haemodynamic disturbance, as long as STEMI is the clear cause, and there is no overriding contraindication to intervention. Recommendations for the choice of arterial access site (radial or femoral artery) and the use of coronary thrombus extraction devices are based on expert opinion in the absence of conclusive evidence. An algorithm is provided to demonstrate the full treatment pathway for people presenting with STEMI (Fig 1).

Fig 1. STEMI pathway. *At the time of publication of CG167, Prasugrel for the treatment of acute coronary syndromes with percutaneous coronary intervention (TA182) was referred to be updated. The updated technology appraisal guidance has since been published (TA317; www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta317). LMWH = low molecular weight heparin; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PPCI = primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction; UFH = unfractionated heparin.

Limitations of the guideline

Some of the evidence was old or had methodological flaws, with limited reporting of methodology and variation in definitions. In some areas evidence was of low to very low quality, including data informing the choice of reperfusion therapy, the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors or fibrinolytic drugs prior to PPCI, and the management of people with STEMI who are unconscious or haemodynamically unstable. Where robust evidence was lacking, recommendations were informed by consensus, taking account of expert and patient opinion.

Further research was recommended regarding (1) the choice of reperfusion strategy in people who present very early (within one hour of onset of STEMI symptoms) or who have an anticipated long transfer time for PPCI; (2) the optimal arterial access route; (3) whether intervention on just the culprit coronary artery or on all potentially amenable coronary disease (multivessel PCI) is more effective; and (4) optimal management of people with STEMI who receive no reperfusion therapy (either fibrinolysis or PPCI) and have poor outcomes (around 25–30% of all STEMI cases).

Implications for implementation

The main barrier to implementation is the provision of PPCI services to all eligible people with STEMI within the appropriate timeframe. Additional PPCI services have been commissioned and air ambulance services may benefit those living in more remote areas. PPCI services must be delivered continuously and sustainably (24 hours per day, 7 days per week) to ensure equitable access to all who may benefit, regardless of time of presentation. Data in 2014 showed that 98.5% of those with STEMI in England and Wales receiving reperfusion therapy were treated by PPCI, and only <3% were given fibrinolysis.18 Evidence on volume of procedures emphasises maintenance of individual operator competence as an important influence on the outcomes of a PPCI service. A baseline assessment implementation tool published alongside CG167 aims to enable activity planning to meet the recommendations, and an audit tool highlights key criteria and provides a framework for monitoring.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support received from the guideline development group and the technical team who contributed to the development of NICE clinical guideline 167, convened and funded by NICE, in association with the Royal College of Physicians. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institute.

References

- 1 .Nichols M, Townsend M, Scarborough P. et al. European cardiovascular disease statistics. Brussels: European Heart Network; Sophia Antipolis: European Society of Cardiology, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2 .Scarborough P, Bhatnager P, Wickramasinghe K. et al. Coronary heart disease statistics. Oxford: British Heart Foundation Health Promotion Research Group, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3 .Pearson-Stuttard J, Bajekal M, Scholes S. et al. Recent UK trends in the unequal burden of coronary heart disease. Heart 2012;98:1573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 .Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J. et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe: description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J 2010;31:943–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5 .Lowel H, Lewis M, Hormann A. Prognostic significance of prehospital phase in acute myocardial infarct. Results of the Augsburg Myocardial Infarct Registry, 1985-1988. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1991;116:729–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6 .Norris RM. Fatality outside hospital from acute coronary events in three British health districts, 1994-5. United Kingdom Heart Attack Study Collaborative Group. BMJ 1998;316:1065–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7 .O'Flaherty M, Buchan I, Capewell S. Contributions of treatment and lifestyle to declining CVD mortality: Why have CVD mortality rates declined so much since the 1960s? Heart 2013;99:159–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8 .Jernberg T, Johanson P, Held C. et al. Association between adoption of evidence-based treatment and survival for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 2011;305:1677–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9 .DeWood MA, Spores J, Notske R. et al. Prevalence of total coronary occlusion during the early hours of transmural myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1980;303:897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 .Reimer KA, Lowe JE, Rasmussen MM, Jennings RB. The wavefront phenomenon of ischemic cell death. 1. Myocardial infarct size vs duration of coronary occlusion in dogs. Circulation 1977;56:786–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11 .Rentrop KP, Blanke H, Karsch KR. et al. Acute myocardial infarction: intracoronary application of nitroglycerin and streptokinase. Clin Cardiol 1979;2:354–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12 .Department of Health. Coronary heart disease: national service framework for coronary heart disease modern standards and service models. London: DH, 2000. Available online at www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4094275 [Accessed 22 May 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 13 .Department of Health. Treatment of heart attack national guidance: final report of the National Infarct Angioplasty Project (NIAP). London: DH, 2008. Available online at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_089455 [Accessed 22 May 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 14 .National Clinical Guideline Centre. Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. NICE clinical guideline 181. London: NCGC, 2014. Available online at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG181 [Accessed 22 May 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 15 .National Clinical Guideline Centre. MI secondary prevention: secondary prevention in primary and secondary care for patients following a myocardial infarction. NICE clinical guideline 172. London: NCGC, 2013. Available online at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG172 [Accessed 22 May 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 16 .National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Commissioning guides supporting clinical service redesign: cardiac rehabilitation services. London: NICE, 2013. Available online at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cmg40/resources/non-guidance-cardiac-rehabilitation-services-pdf [Accessed 6 July 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 17 .National Clinical Guideline Centre. Myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation: The acute management of myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. NICE clinical guideline 167. London: NCGC, 2013. Available online at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG167 [Accessed 22 May 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 18 .National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project: Annual public report April 2013 to March 2014. London: NICOR, 2014. Available online at www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/audits/minap/documents/annual_reports/minap-public-report-2014 [Accessed 22 May 2015]. [Google Scholar]