OVERVIEW

Letters not directly related to articles published in Clinical Medicine and presenting unpublished original data should be submitted for publication in this section. Clinical and scientific letters should not exceed 500 words and may include one table and up to five references.

Acute internal medicine (AIM) physicians frequently need to rule out potentially life-threatening pathology more quickly than is possible with a comprehensive standard echocardiogram. Point-of-care examinations using hand-held devices1 are designed to identify key pathologies: pericardial tamponade; severe left ventricular impairment; critical valve disease; right ventricular dilatation as a sign of pulmonary embolism; and inferior vena cava (IVC) size and reactivity as a sign of loading.

It is vital that such scans are performed by operators appropriately trained, qualified and regulated, but no nationally agreed accreditation system in the UK exists. We propose one possible scheme.

Proposed certification in point-of-care cardiac ultrasonography

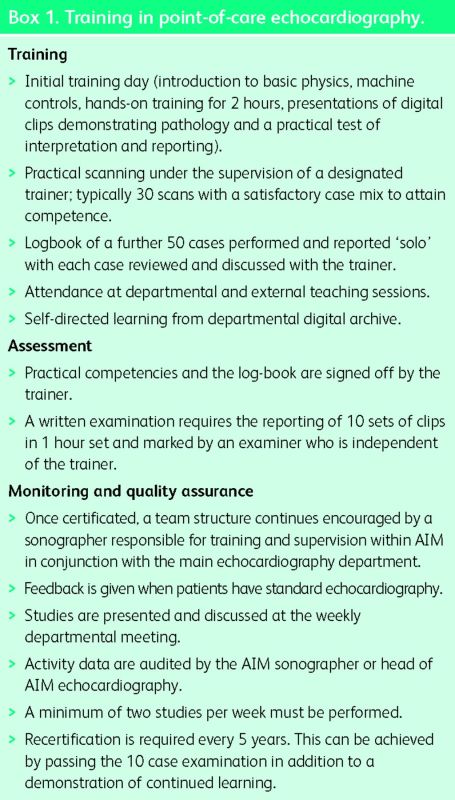

In 2007, we set up a process for specialists in intensive therapy2 which has now been extended to AIM. It agrees with American Society of Echocardiography standards.3 There is an initial training day (Box 1). The candidate is then assigned a supervisor for practice in imaging and colour-Doppler mapping which focuses on four views: parasternal long-axis; parasternal short-axis; apical 4- and 5-chamber; and subcostal, including IVC. Most candidates become competent to obtain views reproducibly after approximately 30 scans after which a log book of 50 scans is collected. All studies are archived and reported using a ‘tick-box’ reporting form. The operator is expected to differentiate three groups: a completely normal study; an abnormal study requiring a standard echocardiogram; and critical disease (eg tamponade) requiring immediate management. Practical training is complemented by a training set of abnormal scans on the departmental archive.

All scans are checked by the supervisor who must attest that the candidate is competent and safe to operate independently within the devolved echocardiography department; this includes regular quality assurance exercises, case discussions and continuing education. There is then a written assessment which requires ten cases to be reported.

Box 1. Training in point-of-care echocardiography.

Limitations and strengths of point-of-care scans

A point-of-care scan allows immediate, potentially life-saving treatment. It may also detect clinically unexpected but important findings4 and aids triaging the urgency with which a full standard echocardiogram needs to be performed. Imaging without Doppler is an established part of advanced life support (FATE).5 However, much of the work validating the technique outside the peri-arrest scenario has been collected by cardiologists or sonographers experienced in transthoracic echocardiography.

We believe that the use of hand-held devices should be subject to many of the same standards as apply to the use of full transthoracic echocardiography. Practitioners must have expert supervision and back-up, and continuing education with quality control through the central echocardiography department. Continuing education needs to be accredited by a recognised body such as the British Society of Echocardiography. The point-of-care scan is not equivalent to an echocardiogram. It is effectively an ultrasonic stethoscope or an extension of the clinical examination. Accreditation is not necessary for the stethoscope, but treatment decisions are rarely executed after auscultation alone without a confirmatory test.

In the face of rising clinical activity, echocardiography departments are already hard pressed to deliver training to cardiac physiologists, clinical scientists and cardiology registrars. The addition of AIM physicians, and perhaps in time medical students, will require a systematic upgrading of training programmes. We believe that echocardiography departments need to be recognised as core hospital services rather than adjuncts of cardiology and must have central funding to match. There need to be designated staff sessions and also examination rooms and an appropriate cardiac ultrasound machine earmarked for training.

Conclusions

We believe that broad standards for the point-of-care scan in AIM should be agreed nationally; however, certification could be performed locally since there are too many candidates to make a national system viable and local supervision is essential. Properly managed, the point-of-care scan could represent as big an advance as the stethoscope, but without systematic training and supervision it could be potentially dangerous.

References

- 1 .Hothi SS, Sprigings D, Chambers J. Point-of-care cardiac ultrasound in acute medicine – the quick scan. Clin Med 2014;14:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2 .Victor K, Rajani R, Bruemmer-Smith S. et al. A training programme in screening echocardiography. Clin Teach 2013;10:176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3 .Spencer K, Kimura B, Korcarz C. et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echo 2013;26:567–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 .Fedson S, Neithardt G, Thomas P. et al. Unsuspected clinically -important findings detected with a small portable ultrasound device in patients admitted to a general medicine service. J Am Soc Echo 2003;16:901–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5 .Sicari R, Galderisi M, Voigt J-U. et al. The use of pocket-size imaging devices: a position statement of the European Association of Echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr 2011;12:85–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]