Abstract

The abuse of adults who are vulnerable or at risk is an important cause of harm to patients. Doctors have a duty to act on concerns about abuse and to seek to protect those in need. We discuss two case examples of how abuse can present in a general hospital setting and use these to consider the steps clinicians should take in the interests of patients. We also describe definitions in relation to safeguarding adults and illustrate principles with which to approach safeguarding practice.

KEYWORDS : Abuse, adult, risk of harm, safeguarding, vulnerable

Introduction

Awareness of the abuse of adults at risk of experiencing harm is growing. In the UK, a number of significant events have brought this often-hidden problem to national attention. The BBC's Panorama programme ‘Undercover care, the abuse exposed’ (www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b011pwt6) revealed the shocking and horrific abuse of people with learning disabilities at Winterbourne View Hospital in Gloucestershire. This led to the conviction of 11 individuals employed by the hospital to care for patients (www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-20092894). Abuses, including physical assault and degrading treatment, were committed over a number of years. A serious case review of the events found that abuse was pervasive within the organisation.1

More recently, the Francis Report2 into the failings surrounding Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust highlighted what can happen when safeguards are inadequate. It emphasised the deficiencies in procedures and practice that resulted in harm to patients. Failures were found not only within the trust itself but also among its commissioners and other parts of the health economy.

Data from the Health and Social Care Information Centre show that safeguarding incidents present across all parts of the health and social care sectors in England.3 In 2011–12, 106,165 referrals for adult safeguarding were made across all 152 councils. Most came from social care staff (n = 46,670), mainly from staff in residential care (n = 19,260). Healthcare staff made many fewer referrals (n = 23,450), possibly representing lack of awareness and issues around identifying and referring suspected abuse. Of the 23,450 referrals made by healthcare staff, only 8,265 came from secondary healthcare staff – about 8% of the total.

Doctors in secondary care need to understand their responsi-bilities within policies and procedures around safeguarding adults, as many of their patients may be considered to be ‘adults at risk’. No secrets, the Department of Health's policy on safeguarding adults, makes explicit that all clinicians have a responsibility to protect those at risk and to take action as appropriate.4 Patients in the general hospital who may be considered at risk could include:

an elderly person who is frail

a person with dementia

somebody with a learning disability

somebody in receipt of home care (social care)

an adult with sensory impairment such as deafness or blindness.

It should be remembered that people at risk can have considerable personal resources and may be able to protect themselves. The concept of vulnerability has been considered to be stigmatising by some (see below) and has been criticised for ignoring a person's strengths. When thinking about safeguarding, it is important to be mindful of the individual's right to self-determination and freedom to make their own choices.

Definitions

Some of the terminology used in safeguarding can be confusing. Technical definitions have changed over time as policy has evolved, but the use of language can be slow to catch up. In practice, older terms are often used interchangeably with new terms.

In 2000, safeguarding concerned the protection of ‘vulnerable adults from abuse’, as described in No secrets.4,5 A vulnerable adult was defined as a person aged 18 years or over:

‘who is or may be in need of community care services by reason of mental or other disability, age or illness; and who is or may be unable to take care of him or herself, or unable to protect him or herself against significant harm or exploitation.’

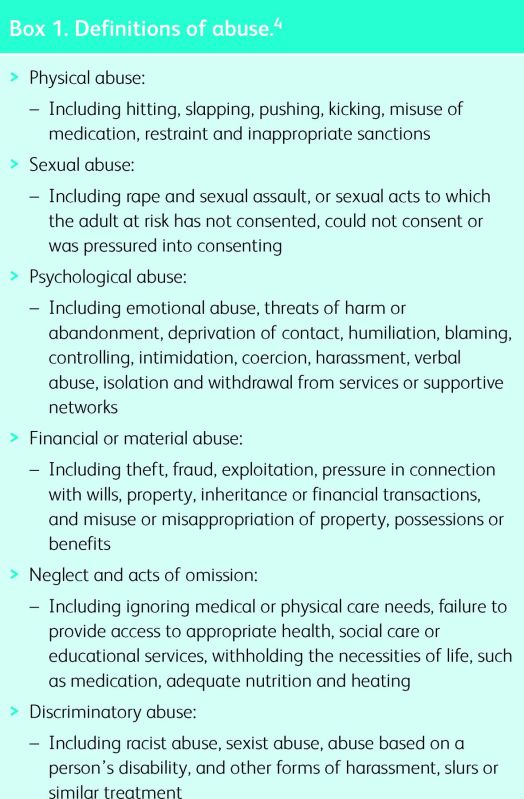

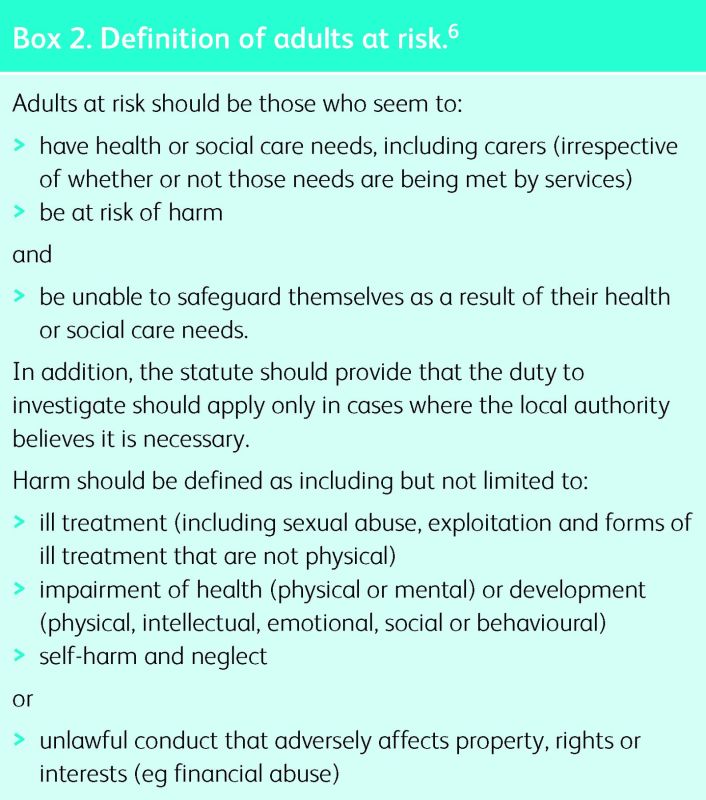

Many doctors will be aware of the concepts of abuse from child protection. Definitions of abuse of adults are broadly similar to those for children and Box 1 summarises the types of abuse. In 2011, the Law Commission recommended that the term ‘vulnerable adult’ be replaced with ‘adult at risk of harm’, as references to vulnerability were seen to be ‘stigmatising, dated, negative and disempowering’ (Box 2).6

Box 1. Definitions of abuse.4

Box 2. Definition of adults at risk.6

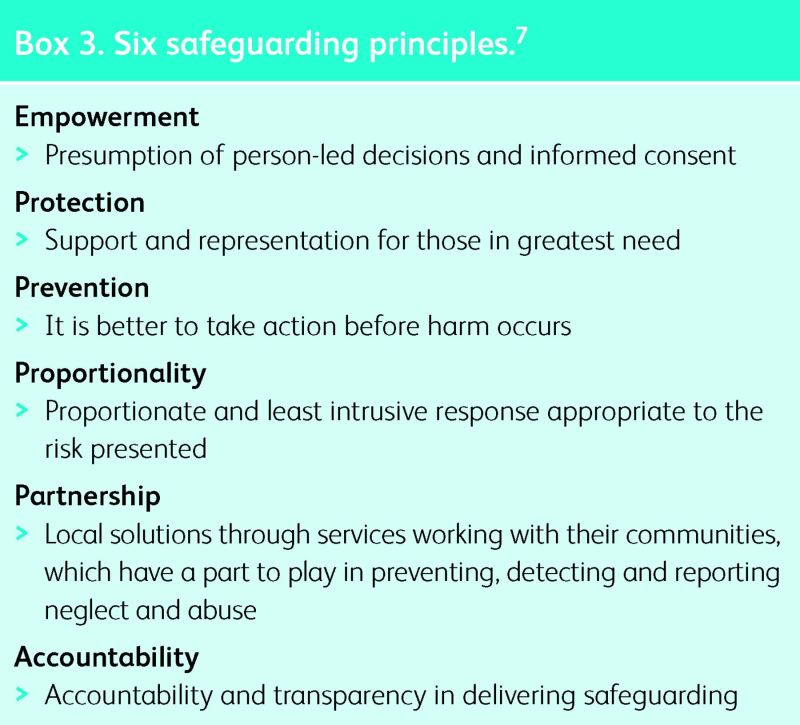

The term ‘safeguarding’ itself is an umbrella term that covers a range of activities intended to protect adults at risk. Such activities include initiatives to prevent abuse, investigations into alleged abuse and interventions (often multidisciplinary) where abuse has occurred. Box 3 shows the key features of safeguarding according to the Department of Health's ‘six safeguarding principles’.7

Box 3. Six safeguarding principles.7

Safeguarding in practice

Safeguarding issues frequently occur obliquely. It is unusual for abuse to be the presenting complaint and concerns are often raised by a professional known to the person, such as a home carer or social worker, or a member of their family or wider social network. Clinicians also need to be alert to the possibility of undisclosed abuse when working with adults at risk of harm.8,9 A hospital admission or visit may be the only opportunity that an adult living in an abusive environment has to discuss these concerns, so it is important to take any allegation of abuse seriously and to make enquiries and share concerns if you suspect abuse that is undisclosed.

In this next section, we consider safeguarding issues in day-to-day practice. Two fictitious cases are used to illustrate and discuss key concepts in safeguarding, outlining management in line with procedures in England and Wales. Elements of safeguarding practice in line with the Department of Health's safeguarding principles are indicated in the discussion by italics.

Case 1: Abuse in a hospital setting

Mr Ahmad is 50 years old and has a learning disability. He has profound communication difficulties, with almost no speech, and difficulties in understanding.

Mr Ahmad was admitted with a suspected myocardial infarction. His carer accompanied him to hospital, bringing some of his belongings and paperwork. After 2 days, he was reported to be incontinent, and the nursing staff began using adult incontinence pants with him, but he became agitated and distressed on wearing these. In addition, he was encouraged to defecate in the incontinence pants and the nurses would later clean him. He subsequently developed excoriation in the perineal area and a urine infection and had a prolonged admission on the ward.

During a subsequent visit, an angry and concerned carer explained that Mr Ahmad makes a distinctive gesture with his head when he needs to use the toilet. He was able to use the toilet himself and had never been incontinent before. The carer said that he had advised the admitting doctor of this and that the information was written down in the patient ‘passport’ left with him at the hospital.

Mr Ahmad was at risk of harm due to his learning disability and communication difficulties, and he was in an unfamiliar environment without his usual sources of support. He suffered degrading and undignified treatment that was inappropriate while in the hospital and consequently suffered further ill health and a prolonged admission. Sadly, all of this harm could have been avoided, as the carer had explained Mr Ahmad's communication needs to a doctor and had reasonably assumed that this information would be shared with those providing care for the patient. This verbal information was supported by written information about his needs, which was kept with him in hospital. Unfortunately no one caring for him had thought to look at this.

The hospital staff seem to have made some effort to meet Mr Ahmad's needs – for example, by providing incontinence pants – but they failed to properly assess his continence needs or to consider why this issue had only arisen in hospital. Poor awareness about learning disability, stigmatised attitudes, poor communication and management systems, as well as a lack of curiosity and accountability about Mr Ahmad, resulted in an inappropriate response that caused him multiple harms. Such harms could have been prevented by better care planning. The categories of abuse in this scenario would include psychological abuse (humiliation and control), neglect and omission (ignoring his physical care needs and failing to provide access to appropriate health services) and discriminatory abuse (based on his disabilities).

A basic guiding principle for safeguarding is to start to do what is right when you become aware of the abuse (when abuse is uncovered, the abused person should be offered protection). In this case, there were opportunities to intervene before he acquired a urine infection by checking the paperwork that he arrived with or contacting his carer to discuss his needs (an example of working in partnership). Once the patient's communication needs became apparent, those nursing him should have been made aware of how he communicated about his toilet needs and supported him to manage this himself again without the need for incontinence pants (promoting empowerment).

This series of events would need to be investigated (a referral is a proportional response when abuse has been suffered) and a safeguarding adult alert would need to be raised (an alert is the raising of a concern, suspicion or allegation of potential abuse or harm). In England and Wales, local authorities, as the lead agency for safeguarding adults at risk of harm, have a duty, but this responsibility can be delegated to another organisation such as an NHS partnership trust.

Safeguarding procedures vary nationally, so it is the responsibility of clinicians to make themselves aware of the local arrangements. Other resources of support include the hospital social worker, who may be able to help and advise on making a referral. In addition, details of local safeguarding arrangements should be available on clinical commissioning group websites.

Case 2: Investigating and preventing abuse

Mrs Adams is 83 years old and has diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), osteoarthritis and poor mobility. She lived with her husband until 12 months ago when he died. Since then she has been living with her son, who moved in with her. He is single.

Mrs Adams has been in hospital for 3 weeks following a head injury she says happened when she tripped and fell at home. This is her fourth admission in the past year. On this admission she has been diagnosed with mild Alzheimer's disease and now requires significant levels of care, so the team needs to plan for her discharge.

Mrs Adams disclosed to a nurse that she was not looking forward to going home, as she spent almost all her time on her own. She said that her son did not let her out of the house, as he was worried that she might fall, so she felt trapped. She also explained that he was asking for money to pay for the care that he will provide for her once she leaves hospital this time. He wants to charge her £1,000 per week; she thinks it is too much but does not want anyone else to do it.

This situation is complex. It is unclear whether Mrs Adams was previously abused by her son. She has possibly suffered neglect (ignoring care needs) and physical abuse (she may be failing to disclose that the head injury was caused by her son). Now she needs to leave hospital but is unsure about returning home. If she is sent home without any safeguards in place, she may experience abuse, including psychological abuse (deprivation of contact and isolation) and financial abuse (exploitation and pressure in connection with financial transactions). However, injuries following a fall are common among elderly people, and the head injury could well be accidental, so it would be worth speaking to her GP, particularly about the reasons for her previous admissions. It is not unusual for caring family members to manage the movements of their loved ones, with their collaboration, in order to minimise accidental harm. At this stage, the arrangements between Mrs Adams and her son and how each party has interpreted these are not clear.

Given Mrs Adams’ diagnosis of dementia, her mental capacity may be a concern. If she is found to have capacity to make decisions about her care, it would be appropriate to ask her for more detail about her circumstances at home before an alert is raised (think about proportionality of the response). This should be done in a private space, where the conversation cannot be heard. She wants her son to provide the care, which may be because she trusts him or because she does not want others to become aware of what he does to her. She may appreciate that she will be lonely when her son is not there, but she may want to accept this or may be open to other ways of relieving her loneliness. Her son should not be present during this discussion so that her relationship with him can be discussed freely. Mrs Adams may wish to have another trusted person – an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) or perhaps a friend – to support her during this difficult conversation. She may volunteer details of abuse in this safe setting, but, if she does not, it would be appropriate to ask her directly about whether she is experiencing abuse, explaining why you are concerned. You may seek permission to speak with others in her network in order to get collateral information.

If Mrs Adams makes it clear that she has not experienced harm from her son, she has mental capacity and no information from other sources suggests otherwise, it may not be necessary to make a safeguarding referral. You may still wish to discuss with a colleague with expertise in social work and safeguarding for advice on preparing a discharge plan.

If it is suspected that she lacks capacity to make decisions about her care, this should be assessed properly.10 This is important, as her son would ordinarily need to be consulted about decisions about her best interests if he is her only living relative. However, this would be inappropriate if he is suspected to be an abuser. Alternative provisions may need to be made under the Mental Capacity Act if she lacks capacity to make decisions about her care, such as the involvement of an IMCA.11 In this scenario, it would be appropriate to raise a safeguarding alert in order for the allegation to be explored and investigated.

If a safeguarding investigation went ahead, the investigator (typically a social worker but sometimes another professional with the appropriate skills and experience) would host an initial multidisciplinary safeguarding meeting. Mrs Adams would be informed that a meeting would be held and that she would be supported to be fully involved in her own safeguarding, but she would not be required to attend if she did not wish to do so. It is likely that those involved in her care would be required to attend, including a nurse and doctor from the hospital, as well as her GP and any other professionals from the community. If there is suspicion that a crime has been committed, as in some cases of physical and financial abuse, the police would need to be invited at this stage, otherwise evidence may be destroyed. Most police forces have officers specifically trained for safeguarding work. The police will advise whether it is appropriate to pursue a criminal investigation or whether another action short of this should be taken. In all cases, a safeguarding protection plan should be put in place (both for Mrs Adams’ protection and to prevent further abuse). The investigating team would monitor the implementation of the plan and reconvene a meeting with partners as required.

As Mrs Adams’ care needs have changed with the changes in her health, it would be appropriate to have her social needs assessed under ‘Fair access to care services’.12 This would ordinarily be undertaken by a social worker or another clinician on behalf of the county council. Where eligibility criteria are met, a needs outcome assessment and financial assessment would be undertaken. If Mrs Adams had eligible needs, she would potentially be entitled to a personal budget to pay for her care, depending on her financial circumstances. She could choose to use this to pay her son to provide personal care and could be supported in negotiating an appropriate payment agreement. Alternatively, she could purchase care from another provider (an example of empowerment).

Summary

Safeguarding is an important activity that aims to protect adults at risk. Responses and interventions are tailored to the individual, and a supporting ethical and policy framework guides the way forward. Clinicians do not need to know about the execution of safeguarding referrals in detail, but they must know what to do when abuse is suspected, how to act to prevent abuse and when to make a safeguarding referral.

References

- 1.Flynn M. South Gloucestershire Safeguarding Adults Board. Winterbourne View Hospital. A serious case review. Bristol: South Gloucestershire Council, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: Stationery Office, 2013. www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/ [Accessed 24 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adult Social Care Statistics Team Abuse of vulnerable adults in England 2011-12: experimental statistics, final report. London: Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2013. www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB10430 [Accessed 24 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health No secrets: guidance on developing and implementing multi-agency policies and procedures to protect vulnerable adults from abuse. London: DH, 2000. www.gov.uk/government/publications/no-secrets-guidance-on-protecting-vulnerable-adults-in-care [Accessed 24 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health Safeguarding adults: Report on the consultation of the review of ‘No secrets’. London: DH, 2009. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_102981.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Law Commission Adult social care. London: Stationery Office, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health Adult safeguarding: Statement of government policy on adult safeguarding. London: DH, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boland B, Burnage J, Chowhan H. Safeguarding adults at risk of harm. BMJ 2013;346:f2716. 10.1136/bmj.f2716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.British Medical Association Safeguarding vulnerable adults – a tool kit for general practitioners. London: BMA, 2011. http://bma.org.uk/-/media/files/pdfs/practical%20advice%20at%20work/ethics/safeguardingvulnerableadults.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department for Constitutional Affairs Mental capacity act 2005, code of practice. London: The Stationery Office, 2007. www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/protecting-the-vulnerable/mca/mca-code-practice-0509.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speaking Up Making decisions: the Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) service. Birmingham: Office of the Public Guardian, 2007. www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/protecting-the-vulnerable/mca/making-decisions-opg606-1207.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Community Care, Services for Carers and Children's Services (Direct Payments) (England) (Amendment) Regulations 2013, SI 2009/1887. www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2013/2270/regulation/1/made [Accessed 24 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]