ABSTRACT

Destructive communication is a problem within the NHS; however previous research has focused on bullying. Rude, dismissive and aggressive (RDA) communication between doctors is a more widespread problem and underinvestigated. We conducted a mixed method study combining a survey and focus groups to describe the extent of RDA communication between doctors, its context and subsequent impact. In total, 606 doctors were surveyed across three teaching hospitals in England. Two structured focus groups were held with doctors at one teaching hospital. 31% of doctors described being subject to RDA communication multiple times per week or more often, with junior and registrar doctors affected twice as often as consultants. Rudeness was more commonly experienced from specific specialties: radiology, general surgery, neurosurgery and cardiology. 40% of respondents described that RDA moderately or severely affected their working day. The context for RDA communication was described in five themes: workload, lack of support, patient safety, hierarchy and culture. Impact of RDA communication was described as personal, including emotional distress and substance abuse, and professional, including demotivation. RDA communication between doctors is a widespread and damaging behaviour, occurring in contexts common in healthcare. Recognition of the impact on doctors and potentially patients is key to change.

KEYWORDS: Medical education, rudeness, communication, incivility

Introduction

Destructive or negative workplace communication is recognised to be a problem both in the NHS and other organisations1–4 and has attracted concern following recent care scandals such as Mid Staffordshire and Morecombe Bay.5,6

Negative workplace behaviours encompass a broad spectrum and most of the research on negative communication between doctors has analysed bullying or undermining as a discrete subset.7–10 However, relatively little work has been done to describe more widespread rude, dismissive and aggressive (RDA) communication between doctors that can also be defined as workplace incivility.11 RDA communication is distinct from bullying which is a more persistent and power-based form of abuse most commonly occurring within a department.2,12

Doctors who are recipients of bullying and negative communication have increased levels of stress and depression, and an increased desire to leave medicine.9 There is increasing recognition that this kind of adverse staff interaction leads to worse patient outcomes and can represent a patient safety threat.13–15

In order to find out the scale of RDA communication in hospitals, and the impact it has on doctors, we conducted a mixed methods study at three teaching hospitals. The study involved surveying doctors to report their experiences of negative communication and conducting focus groups.

Methods

Survey

An online-hosted questionnaire combined multiple choice questions and free text boxes to gather information on:

Frequency of RDA.

Context of RDA – who perpetrates rude behaviour?

Impact of RDA.

The cohort of doctors to whom the questionnaire was circulated was defined by lists of current employed doctors obtained by the postgraduate medical department and the office of the medical director in each trust. It was distributed to three core groups – junior doctors (defined as all in posts <specialty training year 3 (ST3)), registrars (defined as training posts ≤ST3) and consultants.

Doctors received an email invitation to complete the survey and then up to two email reminders.

The questionnaire was circulated at three large teaching hospitals, two in London and one outside London over a period between November 2013 and February 2015, henceforth known as hospitals A, B and C.

Results were analysed by one of the investigators using Microsoft Excel.

Focus group

The focus groups were held in the early evening on a weekday and the groups were run by a trained facilitator. Two focus groups were held: one for trainee doctors, with six participants; another for consultants, with four participants. The participants were recruited by email from one of the three hospitals. Questioning was semi-structured based on the data gathered from the survey to explore a greater depth of data in key areas:

Experiences of rudeness.

Context of rudeness – what is seen as triggering rude behaviour?

Impact of rudeness.

Other topics or themes which arose were explored as far as useful and relevant. Questioning was open and non-judgemental to minimise bias from the facilitator's own opinions and perceptions. The focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Two investigators independently coded for themes, and met to resolve disparities and achieve consensus, and a third investigator agreed the final analysis. Quotes were tagged with T or C for trainee or consultant respectively, followed by a numerical identifier.

Approval for the project was granted as service evaluation by the trust research and development department. Focus group participants gave written consent to be recorded and their discussion analysed and published verbatim.

Results: survey

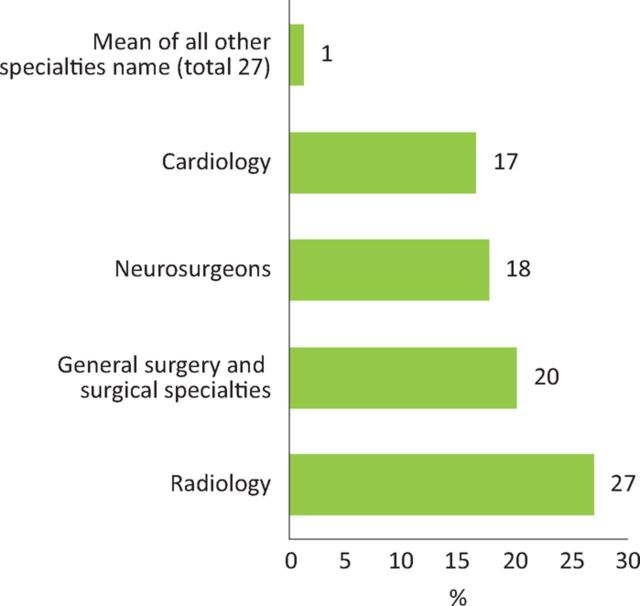

We received 606 responses in total (see Table 1). RDA behaviour was reported to be common. 31% of doctors describe being personally subject to this behaviour multiple times per week or more often (Fig 1). The rates are similar across the three hospitals studied. All grades of doctor are affected but junior and registrar doctors are affected more than twice as much as consultants, with 43% of junior doctors and 38% of registrars experiencing RDA a few times per week or more, compared to 18% of consultants (Fig 1).

Table 1.

Response numbers and rates for each hospital and grade of doctor surveyed.

| Hospital | Junior respondents | Registrar respondents | Consultant respondents | Total respondents | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 90 | 47 | 113 | 250 | 21 |

| B | 28 | 29 | 70 | 127 | 15 |

| C | 76 | 60 | 93 | 229 | 12 |

| Total | 194 | 136 | 276 | 606 | 15 |

Fig 1.

Combined data from three hospitals in answer to the question: How often do you personally experience rude, aggressive or dismissive communication in interactions with other members of staff? Visually represented are (a) all respondents’, (b) junior doctors’ and (c) consultants’ answers expressed as a percentage. DNA = did not answer.

The behaviour is experienced from a wide range of sources within the hospital. A minority of rudeness, dismissiveness or aggression originates from within the individuals’ own department (16%) and a larger proportion comes from interaction with other departments and specialities (49%).

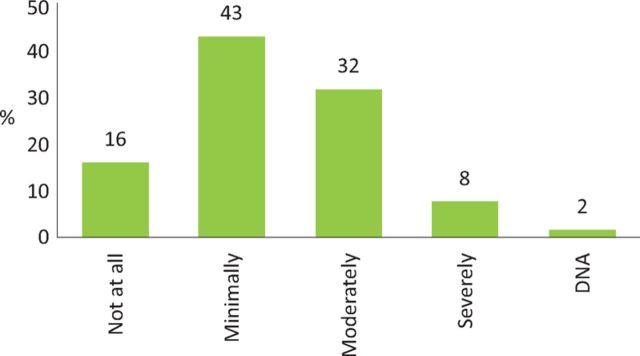

Certain specialties were repeatedly and consistently named as more likely to engage in this behaviour and these were: radiology, general surgery, neurosurgery and cardiology (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Combined data from three hospitals in answer to the question: In your experience have you noticed any particular departments and/or types of staff who are more likely to be rude or dismissive to you or colleagues? Visually represented are all respondents’ answers expressed as a percentage.

Despite negative behaviour being common and widespread in the survey, respondents were very unlikely to recognise themselves as perpetrators of this behaviour with 86% of respondents saying they either never communicated in this way or only did so a few times per year.

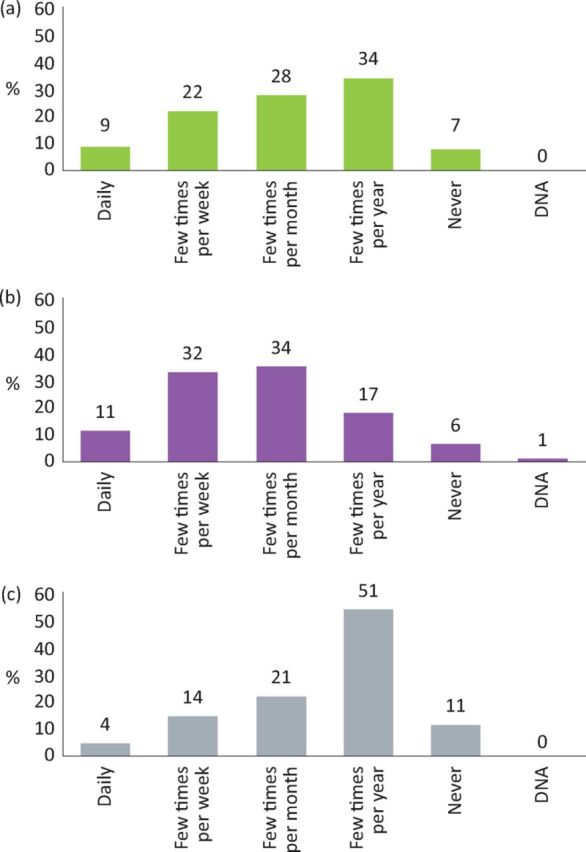

RDA behaviour had a marked adverse effect on those subject to it, with 40% of respondents saying that this behaviour moderately or severely affected their working day (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Combined data from three hospitals in answer to the question: How much does this behaviour affect your experience of the working day at the hospital? Visually represented are all respondents’ answers expressed as a percentage. DNA = did not answer.

Feeling sad, angry or demotivated was widely described, and 7% report that this behaviour had led them to make a mistake at work.

Results: focus group

‘What is rudeness?’

A spectrum of behaviours was described. Overt aggression, such as raised voices and swearing was clearly described:

One of my registrars rang…to get a [specialty] opinion at 4 o'clock in the morning and spent 10 minutes listening to the [specialty] registrar telling her that she was, um, sorry excuse my language: ‘f***ing useless, and was a f***ing waste of space. What are you doing ringing me at this f***ing time in the morning?’ – C2

Other more insidious examples of rudeness included undermining, unwillingness to help, sexism and racism:

I've had situations where people…haven't listened to me because I'm a woman. Other colleagues who've not been listened to because their particular ethnicity – T6

Concerns were raised that legitimate negative feedback could be confused with rudeness:

I got accused of bullying and harassment by one of the F1s, um, because I said, very politely, on the consultant ward round…I don't think you did that right…next time you ought to try this and I'm sure it will be fine. – C2

‘Why does rudeness happen?’

Workload

There was widespread recognition that doctors who were busy or overworked were more likely to be rude:

…you're trying to do 15 things at once…my bleep's going crazy…everyone's bleeding [and colleagues] want blood products…the lab's phoning me [about] blasts on the [blood] film, Mr So-and-so is febrile, some external bone marrow transplant patient is c****ing out in St Elsewheres. And that's when I'm rude. – T6

Lack of support

Rudeness was often described in the context of being unsupported or attempting to support others, outside of conventional supervisory roles:

It's just a horrible feeling and…I just felt like I was making myself vulnerable because I'm having to do two people's jobs. I've got no support…I didn't really feel like I was being myself I felt like I was being quite mean really because I had to be. – T2

Patient safety

In circumstances where patient safety or dignity is acutely threatened, direct and rude communication was more likely. This was the only context for rudeness in which there was support for its presence:

And that was rude. I was rude. But [a] woman could have died. That woman could have died without her fluids and these are meant to be speciality [clinicians]…Christ's sake. Set up a load of fluids. Whack a catheter in. Jesus wept. I was, you know…I was cross. But I was rude. She could she could have easily have put in a complaint about me. – T6

I found her telling off my patient…I did raise my voice and I did have to say: please would you stop talking to my patient like this…I felt I was being rude, but I felt it was justified – C3

Hierarchy

Consultants described rude behaviour being experienced far less once they had become consultants:

…having worked here as a junior and then as a consultant, it always amazed me that the attitude of people underwent a miraculous transformation once you announced that you were consultant…on the telephone or in person. – C2

Trainees frequently described a power imbalance in interactions where rude behaviour occurred.

Culture

Some individuals and departments were described as habitually rude, with a permissive and low threshold attitude to this behaviour. They could be regarded as having a culture which perpetuates rude behaviour:

…the [specialty] registrar…absolutely blew my SHO out down the phone. You know, told her she was useless…I rang up the consultant [specialist] who was on call for the day, and his response was ‘well what do you expect? If people roll over and show me their belly, I will encourage people to put their claws in.’ – C2

I do think some of it is a culture…for example, the [specialty] unit…There is a culture of being aggressive and abrasive…and that is accepted…that's how you are in the [specialty] unit. – C2

‘What effect does rudeness have?’

There were broadly two areas of impact discussed: personal and professional.

Personal impact

The significant emotional impact of rude and dismissive communication:

…if you have had a day where you've had people be rude to you or you've had like a load of referrals to do and they've been really tough you just go home miserable basically…And then you just can't be bothered to do anything. Like I might not be sitting there thinking about it but clearly like subconsciously maybe I am, cos I just go home and I don't want to do any exercise, I don't really want to eat any dinner, I'm just like, I'm just gonna sit here and can't even be bothered to watch TV. – T1

Potentially harmful behaviours were also described:

…we don't steal diamorphine but definitely there's a direct correlation to…if someone's had a rubbish day the amount of times we'll be like [let's drink] wine? – T5

Professional impact

Rudeness could contribute to demotivation with examples of individuals leaving a specialty, or the profession altogether in response to this behaviour:

…now [name removed] is leaving and going to [another hospital] and he's got very disheartened and feels like the whole thing has been quite an unpleasant experience for him because of the interactions [with] his own colleagues who…should be supporting him. – T6

Inefficient working practice and avoidant behaviours were described:

The referral process to…another big specialty, perhaps with a culture of aggressiveness, is like [a junior doctors] biggest nightmare. They're putting it off. They don't want to do it. You might be their consultant saying, ‘well have you made that referral?’ And, it won't have got done. They won't actually admit it…it all stems from, ‘I have just got myself so worked up, I don't think I can speak to this powerfully important [specialist].’– C3

Discussion

Our survey reports a high prevalence of RDA communication affecting 31% of doctors on a daily or weekly basis. This rate is far higher than rates of bullying which have been estimated as only affecting 1–3% of doctors on a daily or weekly basis.1 The data suggests that RDA communication encompasses a wide spectrum of behaviours, for which bullying is a subset of the wider problem.

Exposure to RDA communication was highest among junior doctors, whereas consultants described their seniority as relatively protective against rudeness. This illustrates how status and medical hierarchy are intrinsically linked to negative communication.3

We have shown that across multiple hospital trusts a subset of predictable specialties are more likely to be rude, dismissive or aggressive in their communication: radiology, general surgery, neurosurgery and cardiology. This finding partly conforms to a survey of nurses and medical students in the USA which identified general surgeons, neurosurgeons and obstetrics and gynaecology as the specialties most likely to be disruptive and unprofessional.16,17

Five key themes emerged in response to ‘Why rudeness happens’: workload, lack of support, patient safety, hierarchy and culture. Being overworked and undersupported are both associated with rudeness and they are both relatively common workplace experiences. However, not all specialties which are acute and high intensity are reported to exhibit rudeness and it may be that differences in departmental culture account for this. We suggest that RDA is not an effective or reasonable coping strategy in response to overwork. Venting of anger has been shown to fuel aggression rather than dissipate it and the expression of rudeness is likely to be counterproductive.18

We have shown that RDA behaviour had a marked adverse effect on those subject to it, with 40% of respondents saying that this behaviour moderately or severely affected their working day. The qualitative data describes personal misery and professional demotivation. We know from experimental studies that being subject to rudeness impairs cognitive skills such as memory and attention and also harms cooperation and the willingness to help others.19 The Joint Commission (which accredits healthcare organisations in the United States) issued an alert in 2008 warning that rude language and hostile behaviour among healthcare professionals pose a serious threat to patient safety and quality of care.14

The limitations of our study include the low response rate to the survey and small sample size in the focus groups. There is potential for selection bias in both because doctors affected by negative behaviour may be more motivated to participate. Our results were reproduced across three separate teaching hospitals, though we have not investigated experiences at smaller district general hospitals.

Concern to avoid rudeness should not be interpreted as a reason to avoid direct communication in an urgent or emergency situation; nor should concerns about rudeness be considered a potential reason to avoid addressing poor standards of clinical care. Patient safety is paramount and any programme to reduce RDA would recognise the need for direct and assertive communication in both urgent clinical situations and in response to poor clinical standards.

Describing a programme to change behaviour is beyond the scope of this paper but our data do point to some key areas. If trusts can minimise contributing factors such as overwork and lack of support for doctors this may go some way to ameliorating RDA communication in the workplace. However the entanglement of rudeness with certain speciality culture and hierarchy within medicine means that much more overarching change is needed to address the issue.3 Increasing awareness together with promoting a programme of culture and attitude change would be expected to be both difficult and potentially the most rewarding intervention.20

Conclusion

There may be a perception that rudeness is a mild word, for a mild problem; that as it is a part of everyday life and resilience to it should be a normal part of our reactions and behaviour. We have shown that it is a widespread problem with a large impact on individuals and healthcare organisations. Changing this behaviour is likely to be challenging. The recognition that RDA behaviour is damaging and counterproductive is an essential initial message which needs dissemination.

References

- 1.Carter M, Thompson N, Crampton P, et al. Workplace bullying in the UK NHS: a questionnaire and interview study on prevalence, impact and barriers to reporting. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002628. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnes B, Pope R: Negative behaviours in the workplace: a study of two primary care trusts in the NHS. Int J Public Sect Manag 2007;20:285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearson CM, Porath CL. On the nature, consequences and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for “nice”? Think again. Academy Manag Executive 2005;19:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortina LM, Magley VJ, Williams JH, Langhout RD. Incivility in the workplace: incidence and impact. J Occup Health Psychol 2001;6:64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirkup B. Morecombe Bay Investigation Report. London: Stationary Office, 2015. Available online at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/408480/47487_MBI_Accessible_v0.1.pdf [Accessed 21 September 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis R. Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry. London: Stationary Office, 2013. Available online at www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com [Accessed 21 September 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quine L. Workplace bullying in junior doctors: questionnaire survey. BMJ 2002;324:878–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quine L. Workplace bullying, psychological distress, and job satisfaction in junior doctors. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2003;12:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paice E, Aitken M, Houghton A, Firth-Cozens J. Bullying among doctors in training: cross sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ 2004;329:658–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paice E, Smith D. Bullying of trainee doctors is a patient safety issue. Clin Teach 2009; 6:13–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson CM, Andersson LM, Wegner JW. When workers flout convention: a study of workplace incivility. Hum Relat 2001;54:1387–419. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crutcher RA, Szafran O, Woloschuk W, Chatur F, Hansen C. Family medicine graduates’ perceptions of intimidation, harassment, and discrimination during residency training. BMC Med Educ 2011;11:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon-Woods M, Baker R, Charles K, et al. Culture and behaviour in the English National Health Service: overview of lessons from a large multimethod study. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:106–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joint Commission Sentinal Event Alert 40: behavours that undermine a culture of safety. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.West M, Dawson J, Admasachew L, Topakas A. NHS Staff management and health quality services. Available online at www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-staff-management-and-health-service-quality [Accessed 21 September 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts NK, Dorsey JK, Wold B. Unprofessional behavior by specialty: A qualitative analysis of six years of student perceptions of medical school faculty. Med Teach 2014;36:621–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenstein AH, O'Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:464–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushman BJ. Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2002;28:724–31. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porath CL, Erez A. Does rudeness really matter? The effects of rudeness on task performance and helpfulness. Academy of Manag J 2007;50:1181–97. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leape LL, Shore MF, Dienstag JL, et al. A culture of respect, part 2: creating a culture of respect. Academic Med 2012;87:853–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]