Abstract

The UK's population is ageing and an adequately staffed geriatric medicine workforce is essential for high quality care. We evaluated the current and future geriatric medicine workforce, drawing on data relating to the UK population, current geriatric medicine consultants and trainees, recruitment into the specialty and trainee career progression. Data were derived from various sources, including the British Geriatrics Society Education and Training Committee biannual survey of training posts. The demographic of consultant geriatricians is changing and so too are their job plans, with more opting to work less than full time. The number of applicants to geriatric medicine training is increasing, yet increasing numbers of posts remain unfilled (4.7% in November 2010 and 14.1% in May 2013). The majority of geriatric medicine trainees secure a substantive consultant post within 6 months of obtaining their certificate of completion of training This work highlights challenges for the future: potential barriers to trainee recruitment, unfilled training posts and an ageing population and workforce.

KEYWORDS : Geriatric medicine, certificate of completion of training, CCT, workforce, training

Introduction

The UK's population is ageing. People aged 65 years and over accounted for 15% of the population in 1985 and 17% in 2010.1 It is estimated that 23% of the population will be aged 65 years and over by 2035. The changing demographic of the UK's population is likely to present the National Health Service (NHS) with huge challenges, given the frailty and complex care needs of many elderly patients.2 It has been estimated that two-thirds of acute hospital inpatients in England and Wales are aged 65 years or over.3 Difficulties in recruiting doctors into relevant medical specialties, such as geriatric medicine, have been highlighted recently by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP).4 In a survey of foundation year two (FY2) doctors, the work-life balance of a medical registrar was cited by many as a deterrent to doctors taking up specialties that include general hospital medicine.5

There are a number of challenges to the recruitment of doctors to specialist training programmes that are specific to geriatric medicine. In response to the streamlining of postgraduate training introduced by the reforms set out in Modernising Medical Careers,6 the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) highlighted that it can no longer be assumed that doctors will receive exposure to and training in geriatric medicine post-qualification.7 The BGS suggest that greater emphasis should therefore be placed on undergraduate geriatric medicine education. However, examination of previous surveys of undergraduate geriatric medicine (in 19888 and 20069) demonstrates that the number of medical schools teaching geriatric medicine has declined. There is also evidence that some medical students, at an early stage of their training, may possess negative attitudes towards elderly patients10 and that students may be deterred from pursuing a career in geriatric medicine because of a perceived lack of both prestige and earning potential.11

Guidance from the RCP12 recommends a minimum of one consultant geriatrician per 50,000 population. The rapidly ageing UK population, the widespread difficulties in recruitment to hospital medicine and the negative attitudes possessed by some towards geriatric medicine may make this target progressively harder to achieve. In this paper, we examined data relating to the UK population, current geriatric medicine consultants and trainees, recruitment into the specialty and trainee career progression. We aim to provide an overview of the current geriatric medicine workforce: to what extent are the problems highlighted above impacting on the specialty?

Methods

The BGS Education and Training Committee (ETC) has conducted regular, 6-monthly surveys of trainee numbers across all UK geriatric medicine training programmes for the past 3 years. We examined data relating to the occupancy of training posts and the career progression of geriatricians after obtaining their certificate of completion of training (CCT). RCP data on the career progression of medical CCT holders and data from round 1 of specialty training in 2013 were also examined. Data were also collated from the 2011 RCP census of consultant physicians and medical registrars and Centre for Workforce Intelligence (CFWI) publications on the geriatric medicine workforce. UK population data and demographics were collated from the UK's Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Results

The ageing UK population

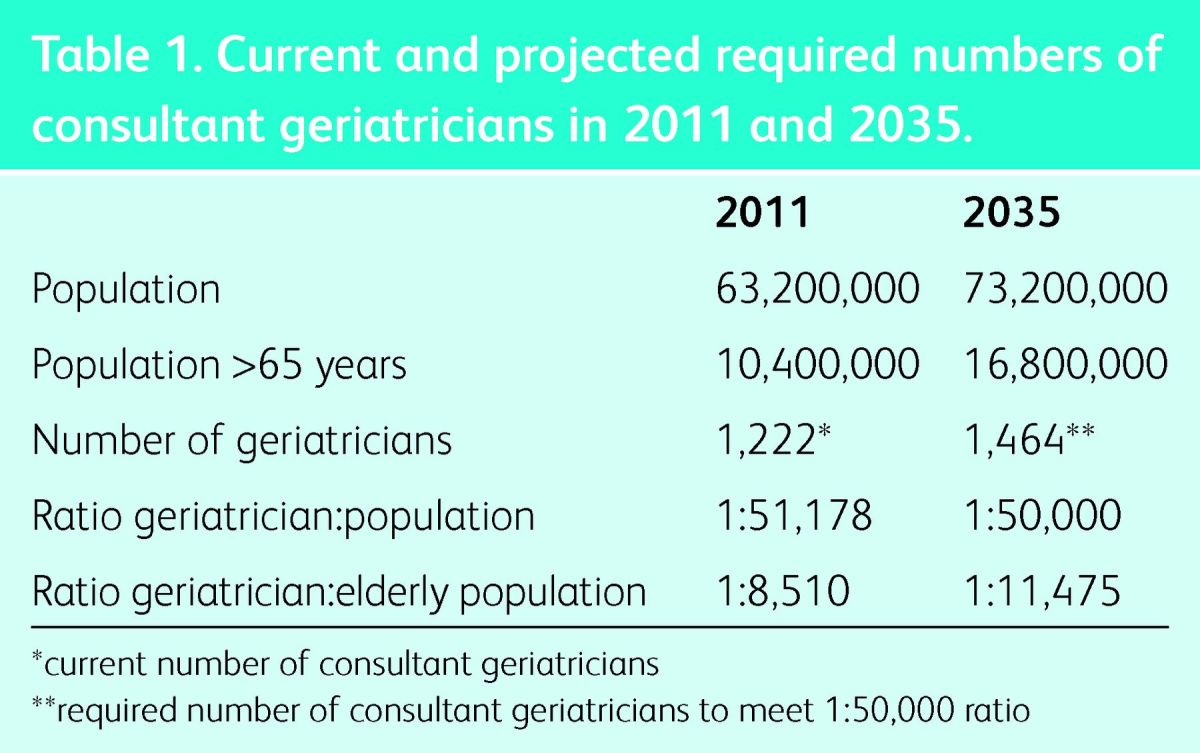

The 2011 ONS census estimated the UK population to be 63.2 million.13 Guidance from the RCP12 suggests a minimum of one consultant geriatrician per 50,000 population. Based on the 2011 RCP census, there were a reported 1,222 consultant geriatricians in the UK, which nationally equated to a ratio of one consultant geriatrician per 51,178. Examination by geographical region in the same survey revealed that only 4/13 regions were achieving the recommended ratio. The 2011 ONS census estimated that those aged 65 years and over made up 16% of the population (10.4 million). Based on these figures, the recommended 1:50,000 ratio equates to one consultant geriatrician for every 8,510 people aged >65 years. ONS projections for 2035 suggest the population will rise to 73.2 million, with 23% aged 65 years or above (16.8 million). To maintain the recommended ratio in 2035, the consultant workforce will need to expand to 1,464. Even if this number is achieved, this only equates to one consultant geriatrician per 11,475 people aged >65 years; 34% more elderly people per consultant than at present (Table 1).

Table 1.

Current and projected required numbers of consultant geriatricians in 2011 and 2035.

The expanding elderly population has already translated into a greater workload for consultant geriatricians, with the number of ‘finished consultant episodes’ for geriatric medicine showing a 29% increase between 1998 and 2009.14

The UK's consultant geriatricians

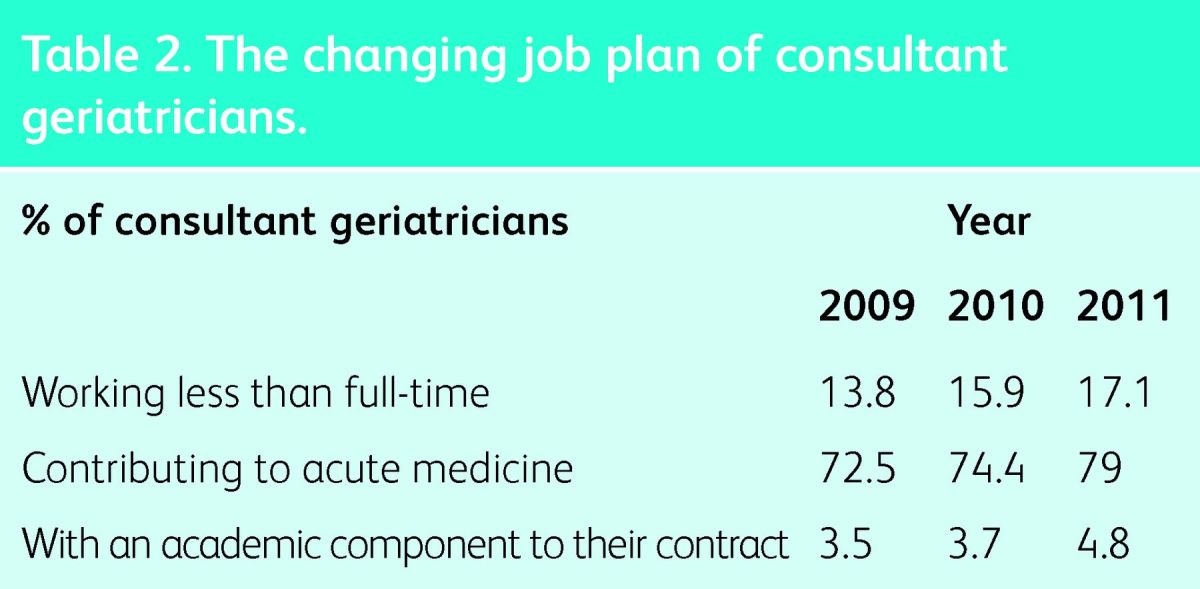

Since 2006 the number of consultant geriatricians in the UK has expanded by more than 10%, from just below 1,100 to 1,222 in 2011. The demographic of the UK's consultant geriatricians is also changing; by 2022, 28.5% of consultant geriatricians will themselves be aged 65 years or older. In the RCP consultant census of 2011,15 134 (11%) of consultant geriatricians indicated that they planned to retire by 2017. Of the 1,222 consultant geriatricians identified, 67% were male and 33% were female; 39.2% of female and 4.9% of male consultants were working less than full time (LTFT). Table 2 displays the proportion of consultant geriatricians working LTFT who were contributing to acute medicine and those who also had an academic component to their contract, according to RCP consultant censuses from 2009–2011.

Table 2.

The changing job plan of consultant geriatricians.

It is evident from examination of serial RCP census data that the number of programmed activities (PAs) per week that consultant geriatricians are contracted to work is falling; a finding that may reflect the increase in LTFT working. In the 2010 census, consultant geriatricians were contracted to work a mean of 10.8 PAs; falling to 10.6 in the most recent census of 2011. Consultant geriatricians also contribute to the delivery of stroke care and are second to only stroke physicians in terms of the mean number of programmed activities (PAs) per week that are allocated to stroke medicine (stroke medicine mean = 8.2; geriatric medicine mean = 3.3; mean across all other specialties = 1.0).

Geriatric medicine registrars

Incumbent

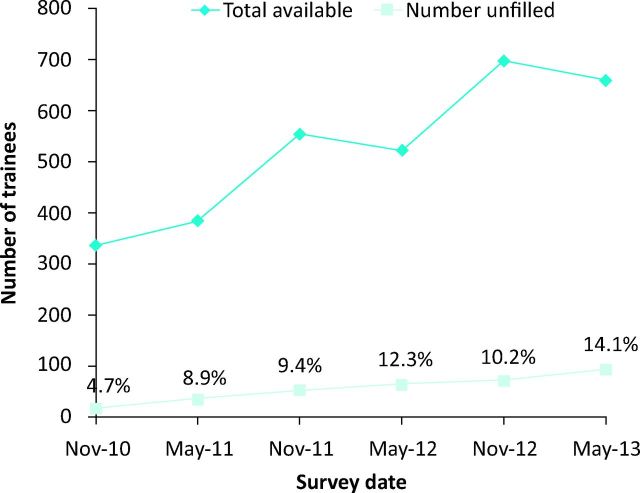

The RCP census of 201115 demonstrated that the gender distribution of geriatric medicine registrars has changed. In 2002, 60% of geriatric medicine registrars were male but within a decade this had decreased, such that female registrars accounted for the majority (56.7%). The BGS ETC bi-annual surveys captured data on the number of current geriatric medicine training posts available across the UK and the proportion of posts that were unfilled (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

UK geriatric medicine training programme trainee numbers (2010–2013).

Incoming

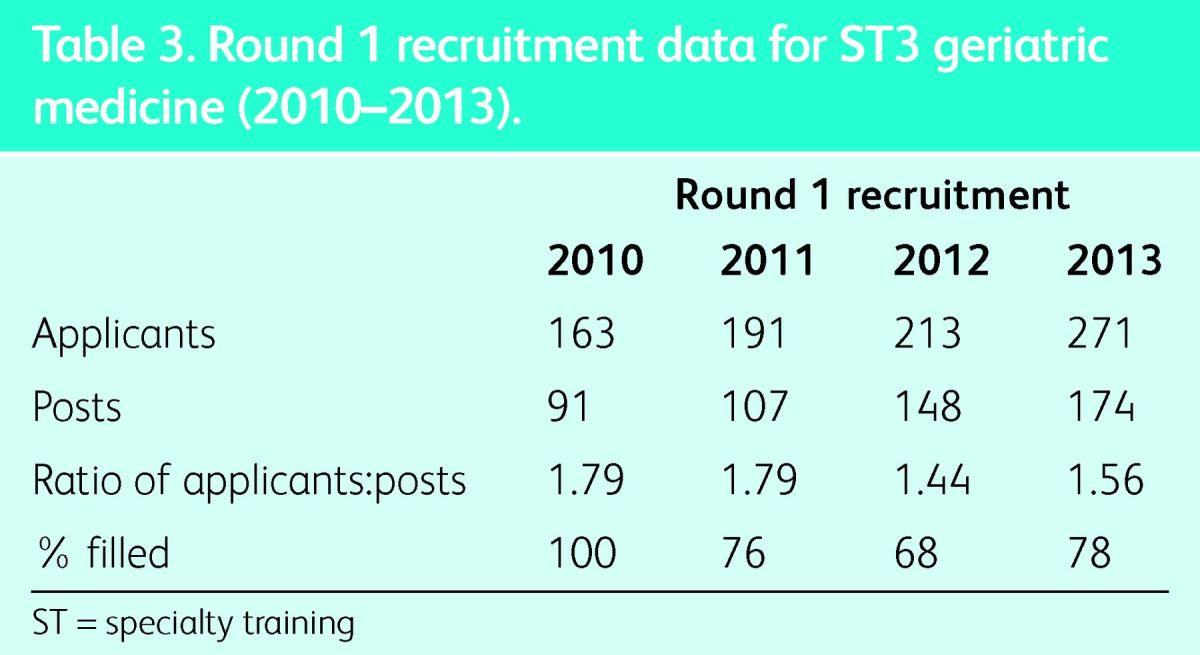

RCP summary statistics16 describe the number of posts, applicants and appointed doctors at Round 1 application to specialty training in geriatric medicine over the most recent 4 years (Table 3). It is evident that year on year more posts have become available and that there have been more applicants for these posts; yet complete fill of these posts has not been achieved in the most recent 3 years of recruitment.

Table 3.

Round 1 recruitment data for ST3 geriatric medicine (2010–2013).

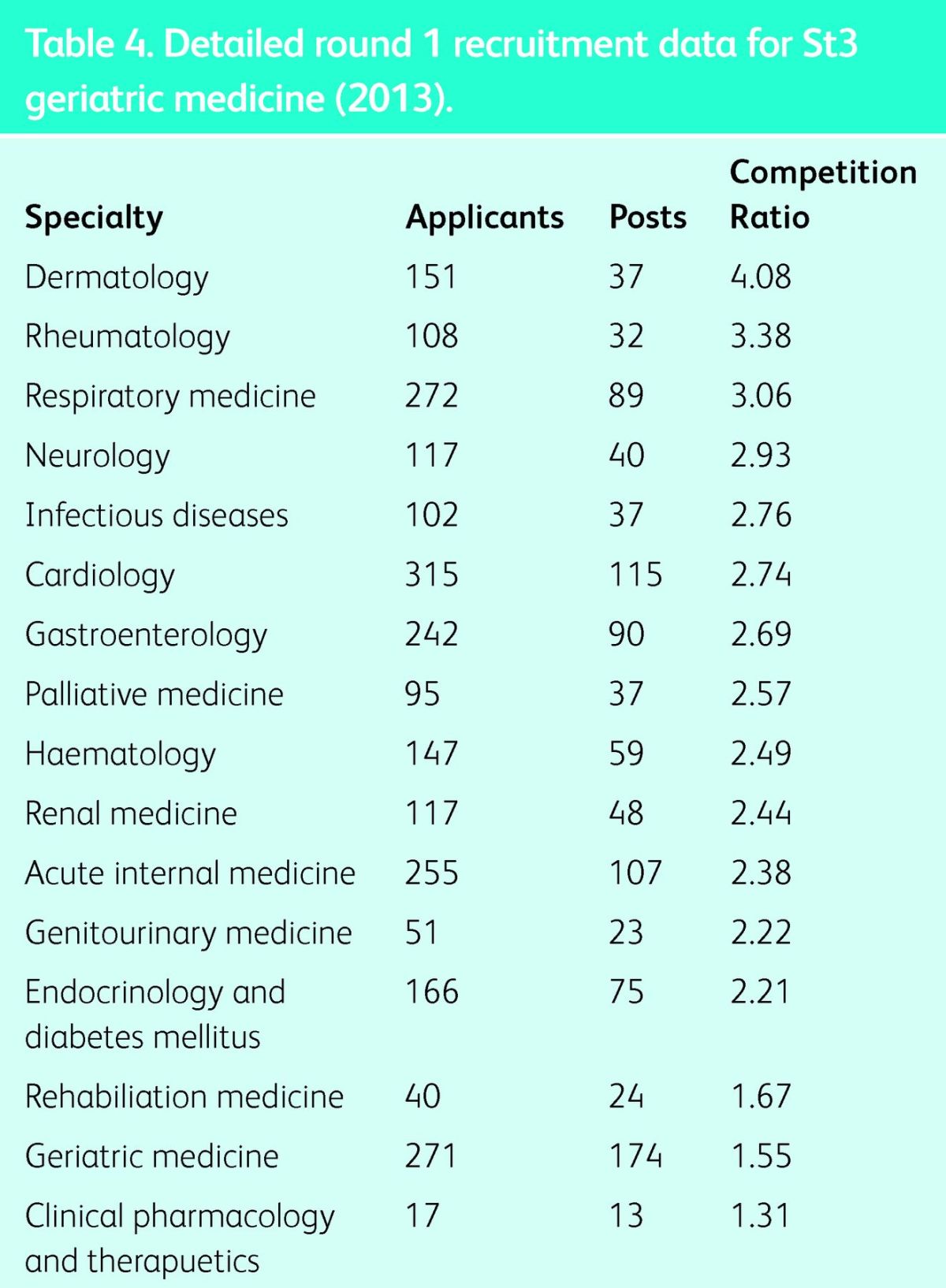

Table 4 presents round one recruitment competition ratios (applicants per post) for the medical specialties for 2013 and reveals that geriatric medicine was among the least -competitive.

Table 4.

Detailed round 1 recruitment data for St3 geriatric medicine (2013).

In round one of recruitment to geriatric medicine in 2013, 209 of the 271 applicants were interviewed. Subsequently 20 applicants declined the invitation to interview, 30 accepted but then subsequently withdrew from the process and 2 accepted but failed to attend the interview. After the interview process, 29 people who were offered a post declined it.16

Outgoing

The BGS ETC bi-annual surveys also captured data on the outcome for CCT holders post-qualification. After obtaining CCT, trainees have a ‘grace period’ of 6 calendar months during which employment in a substantive NHS consultant post is typically sought. Serial survey data showed that the vast majority of CCT holders were successful in obtaining a substantive NHS consultant post without the need for a grace period. Of those not commencing a consultant post during the grace period, none were unemployed and all found employment in a temporary locum consultant post.

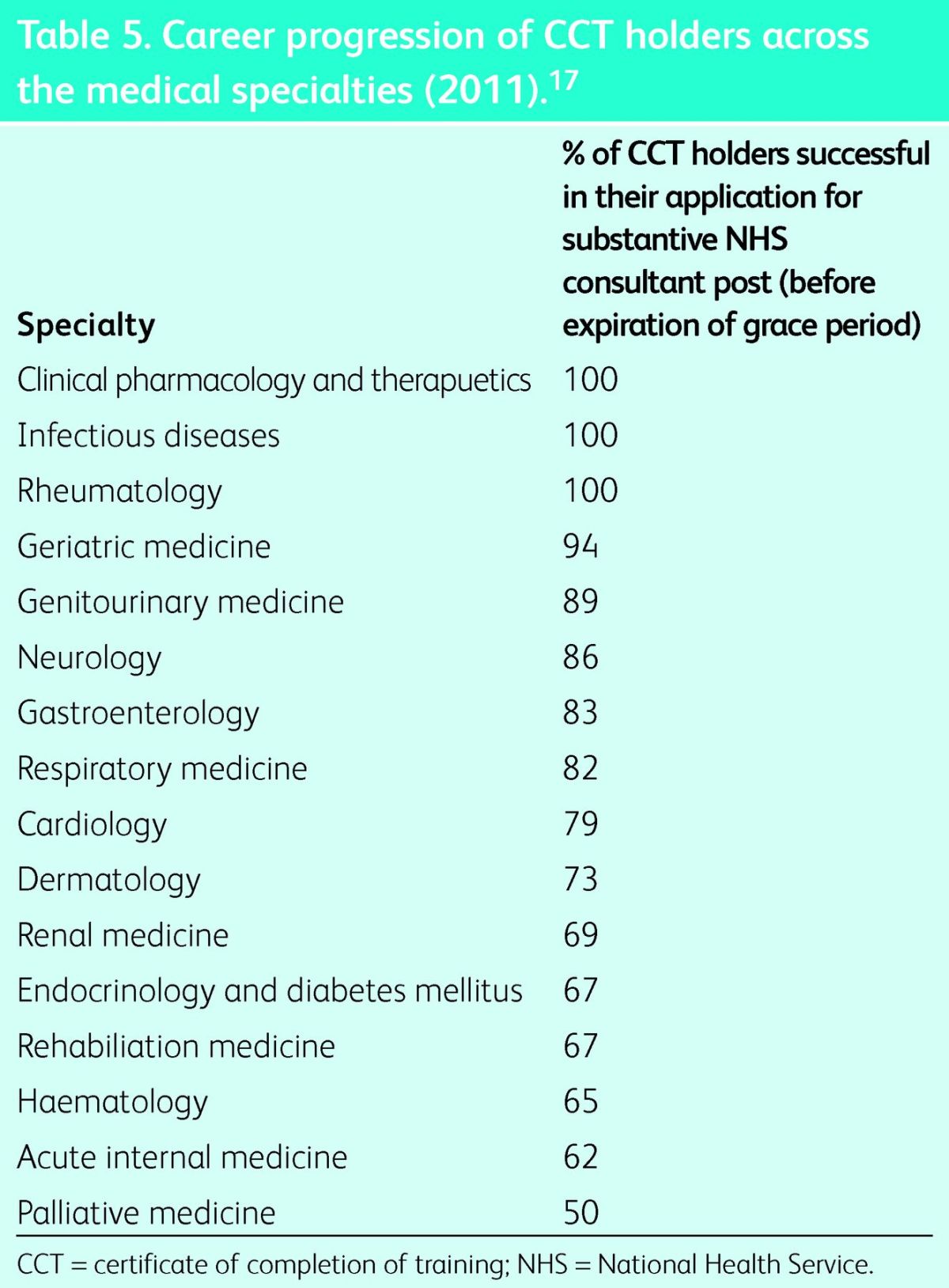

The RCP survey of medical CCT holders career progression17 allows contrast to made between medical specialties. Figures from 2011 show that for many specialties, progression to substantive NHS consultant post within the grace period is not guaranteed (Table 5).

Table 5.

Career progression of CCT holders across the medical specialties (2011).17

Discussion

This work confirms and quantifies the challenges facing the geriatric medicine workforce in planning for the future and highlights that simply aiming for a ratio of one consultant geriatrician per 50,000 people may not translate into an NHS that is adequately staffed to cope with the ageing population. The recent high-profile Francis report18 into inadequate care provision at Stafford and Cannock hospitals highlighted a ratio of one consultant geriatrician per 80,000 population in this organisation. The report suggests that a failure to meet the RCP target resulted in a lack of availability of specialist medical advice for elderly patients, which contributed in part to poor standards of care.

Our data demonstrate that the demographic of consultant geriatricians is changing and so too are their job plans, with more consultants working less than full time and more contributing to both acute and stroke medicine. With respect to the role of geriatricians in acute medicine, it has been suggested that this burden may be eased through expansion of specialists in acute medicine. Taking elderly care physicians off the acute medicine rota would allow them to devote more time to ward-based care and rehabilitation, but would not address the issue of provisioning for acute care. The need for specialist input on care of the elderly in the medical admissions unit was identified in the BGS document The Silver Book.19 Taking geriatricians away from acute medicine may create a deficit in quality of care for older patients at the point of entry to hospital. The demographic of the trainees in geriatric medicine is changing too, with an increasing proportion of women. As our data shows, female consultant geriatricians are more likely to work LTFT; if this pattern is replicated by current trainees when they reach consultant level, this may need to be factored in to workforce planning.

Examining fill rates of geriatric medicine training posts across the UK shows that increasing numbers of posts remain unfilled and that ST3 application competition ratios are low in comparison to other medical specialties. A simplistic interpretation of these findings would be to assume that geriatric medicine is an unpopular choice for applicants; we do not believe this to be the case. The results of this work demonstrate that the number of applicants to geriatric medicine specialty training has in fact increased dramatically; with a 66.3% increase seen between 2010 and 2013. Despite this finding, it is important to acknowledge potential barriers to the recruitment of new trainees into the medical specialties. The recent RCP document The Medical Registrar suggests that the demanding and unrewarding nature of the medical registrar role may deter junior doctors from applying to specialties that include general hospital medicine.4 It is interesting to observe that of the five most competitive medical specialties based on 2013 data (Table 4), three are specialties that do not typically involve general medicine on-call commitments (dermatology, rheumatology and neurology).

Serial survey data presented in this work show that the number of geriatric medicine training posts that are unfilled is increasing (4.7% in November 2010; 14.1% in May 2013). There are a number of potential reasons for this finding. First, there has been rapid expansion in the number of available training posts in recent years, with an increase of 91.2% seen between 2010 and 2013. The increase in available training posts may represent a response to a 2011 report by the Centre for Workforce Intelligence that recommended a National Training Number (NTN) increase of 15 for 3 consecutive years, beginning in 2012.14 Furthermore, government policies such as the National Stroke Strategy20 and the National Dementia Strategy21 may have acted as a catalyst for the increased demand for consultant geriatricians.

Second, it appears that there is a loss of potential geriatric medicine trainees between application and appointment. In 2013 for example, 52/209 (24.8%) of candidates who were offered an interview declined to attend. A further 29 (13.9%) of applicants who were offered posts after interview declined to take up these positions. Further analysis of the RCP data reveals that only 40% of applicants to geriatric medicine applied solely to geriatric medicine. These findings suggest that a minority of candidates may be applying to geriatric medicine as a backup option; candidates who subsequently decline interviews or offers may have been successful in their application to a different specialty.

Third, the number of empty posts does include trainees on maternity or paternity leave as well as those taking time out of programme (OOP) to undertake research. A 2010 survey of medical registrars22 confirms that OOP is becoming a more popular option; 91% of respondents indicated that they were considering taking OOP to undertake activity such as research.

Finally, our data suggest that geriatric medicine trainees obtain substantive NHS consultant posts with little difficulty, with trainees rarely requiring the 6-month grace period. We found no evidence of any unemployed geriatric medicine CCT holders. This finding is in contrast to predictions made by Goddard23 in 2010, who forecast 230 unemployed or ‘excess’ CCT holders in geriatric medicine by 2014. This rapid transition from CCT holder to substantive NHS consultant post is not replicated across all other medical specialties; for example, one-third of trainees completing diabetes training failed to secure such a post.24 This finding is perhaps surprising given the large number of new geriatric medicine CCT holders each year and the comparatively small increases in the consultant workforce year on year. An increase in the number of geriatric medicine consultants taking up posts as stroke medicine consultants may in part explain this finding. Increasing numbers of consultants working LTFT may also be contributory. The retirement of existing geriatricians may also be a factor; RCP census data demonstrate that comparatively, geriatric medicine consultants are older than many of those working in other specialties, with more than 300 geriatricians planning to retire within the next decade.

Greater numbers of training posts, during which flexible training is welcomed, and widely available consultant posts make geriatric medicine an attractive choice. These findings may in part explain the increase in applicants seen over recent years. It is, however, important to acknowledge that empty training posts may result in gaps in medical on-call rotas. Such gaps, and the resulting requirement that trainees in post cover these, are cited in The Medical Registrar, with trainees across the country reporting detrimental effects on their training due to increased on-call time and less specialty-specific time.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, the BGS ETC surveys of training post numbers were not completed by all training programme directors; 22/24 provided data for the most recent survey, but only 11 did so for the November 2010 survey. The conclusions of The Medical Registrar are enlightening, but it cannot be assumed that these are immediately transferrable to geriatric medicine. High-quality qualitative research is needed to explore these issues further; perhaps examining where potential geriatric medicine trainees are ‘lost’, their reasons for leaving the specialty and their perceptions of the specialty.

Conclusions

The increasing number of applicants to geriatric medicine training is encouraging and the evidence presented here suggests that in terms of future job prospects, the specialty is an -attractive option for potential applicants. Our study does highlight some significant challenges for the future, including the increasing proportion of unfilled training posts and the changing demographics of both the general population and of geriatric medicine doctors themselves. It is important to acknowledge that while government policy may have contributed to the expansion numbers of consultant geriatricians, both the current financial climate and the ongoing changes in NHS organisation have the potential to alter dramatically the landscape over the coming years.

We believe that geriatric medicine must continue to take proactive steps to increase awareness of the flexible and rewarding nature of the specialty and to highlight the breadth of the specialty and its subspecialty areas. In an attempt to address this, we are piloting a clinical conference for junior doctors aiming to promote interest and uptake into the specialty (www.aeme.org.uk). Feedback from delegates attending this event may help to provide some insight into junior doctors’ perceptions of geriatric medicine as a career option, and might pave the way for further events and initiatives to develop the next generation of geriatricians for the NHS.

References

- 1.Office for National Statistics Population ageing in the United Kingdom, its constituent countries and the European Union. London: ONS, 2012. www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_258607.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lally F, Crome P. Understanding frailty. Postgrad Med J 2007:83:16–20. 10.1136/pgmj.2006.048587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health National Service Framework for the Older Person. London: DH, 2001. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/198033/National_Service_Framework_for_Older_People.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhuri E, Mason NC, Logan S. et al. The medical registrar: empowering the unsung heroes of patient care. London, RCP, 2013. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/future-medical-registrar_1.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhuri E, Mason NC, Newbery N, Goddard AF. Career choices of junior doctors: is the physician and endangered species? Clin Med 2013;13:330–5. 10.7861/clinmedicine.13-4-330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health Modernising Medical Careers: The next steps. London: DH, 2004. webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4079532.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.British Geriatrics Society The Medical Undergraduate Curriculum in Geriatric Medicine. London, BGS, 2004. www.bgs.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=306:undergraduatecurriculum&catid=49:generalinfo&Itemid=171 [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith RG, Williams BO. Undergraduate teaching of geriatric medicine in the United Kingdom: changes in the years 1981–1986. Med Educ 1988;22:498–500. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1988.tb00792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartram L, Crome P, McGrath A, et al. Survey of training in geriatric medicine in UK undergraduate medical schools. Age Ageing 2006;35:533–5. 10.1093/ageing/afl053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reuben DB, Fullerton JT, Tschann JM, Croughan-Minihane M. Attitudes of beginning medical students toward older persons: a five-campus study. The University of California Academic Geriatric Resource Program Student Survey Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43:1430–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins TD, Crocker-Buque T, Forrester-Paton C, et al. Geriatrics is rewarding but lacks earning potential and prestige: responses from the national medical student survey of attitudes to and perceptions of geriatric medicine. Age Ageing 2011;40:405–8. 10.1093/ageing/afr034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royal College of Physicians Consultant physicians working with patients: the duties, responsibilities and practice of physicians in medicine. London: RCP, 2013. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/consultant_physicians_revised_5th_ed_full_text_final.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office for National Statistics 2011 census: population estimates for the United Kingdom, 27 March 2011. London: ONS, 2012. www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_292378.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centre for Workforce Intelligence Medical Specialty Workforce Summary Sheet: Geriatric Medicine. London: CfWI, 2011. www.cfwi.org.uk/publications/geriatric-medicine-cfwi-medical-fact-sheet-and-summary-sheet-august-2011/@@publication-detail [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federation of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the UK Census of consultant physicians and medical registrars in the UK, 2010: data and commentary. London: RCP, 2011. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/census-2010.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royal College of Physicians ST3 recruitment information and -statistics, 2013. www.st3recruitment.org.uk/about-st3/2013-data.html [Accessed 23 July 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goddard AF, Newbery N. Survey of Medical CCT Holders Career Progression 2009–11. London: RCP, 2011. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/survey-of-medical-cct-holders-career-progression-2009-11.pdf [Accessed 7 July 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationery Office, 2013. www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/ [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 19.British Geriatrics Society Health and Social Care Services Must Adapt to Meet Older People's Urgent Care Needs, 2012. www.bgs.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=207&Itemid=888 [Accessed 28 February 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health National Stroke Strategy. London: DH, 2007. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_081059.pdf [Accessed 5 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health Living well with dementia: a National Dementia Strategy. London: DH, 2009. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/168220/dh_094051.pdf [Accessed 5 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goddard AF, Evans T, Phillips C. Medical registrars in 2010: experience and expectations of the future consultant physicians of the UK. Clin Med 2011;11:532–5. 10.7861/clinmedicine.11-6-532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goddard AF. Consultant physicians for the future: report from a working party of the Royal College of Physicians and the medical specialties. Clin Med 2010;10:548–54. 10.7861/clinmedicine.10-6-548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheer K, George JT, Grant P, et al. One-third of doctors -completing specialist training in diabetes fail to secure a -substantive consultant post: Young Diabetologists’ Forum survey 2010. Clin Med 2012; 12:244–7. 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-3-244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]