Abstract

Physician associates (PAs) are a new profession to the UK. There has been no prior national assessment of the perspectives of doctors who work with PAs with regard to their role. Doctors who supervise PAs were surveyed in late 2012; respondents were found generally to be satisfied with the role of PAs and believed that the addition of the PA to the team benefited doctors and patients. Doctors reported that they have received positive feedback from patients about the role of PAs as well. Respondents believe that the current unregulated status of the profession impairs their ability to use their PA staff to their fullest potential.

KEYWORDS : Physician associate, physician assistant, doctor satisfaction, patient satisfaction, medical regulation

Introduction

Physician associates (PAs) are health professionals with generalist medical education who work within the medical model. They are trained to perform a range of tasks including: taking medical histories, performing examinations, diagnosing illnesses and medical conditions, and requesting and analysing test results. In outpatient settings, they are able to see patients in their own consultations, but always work under the supervision of a fully qualified doctor. PAs have been providing medical care for more than 45 years in the USA (where they are called ‘physician assistants’).1 PAs were introduced to Britain through pilot projects of US-trained PAs working in the West Midlands and Scotland.2,3 Positive evaluations of these projects led the Department of Health to develop the Competence and Curriculum Framework for the Physician Assistant4 and several universities to establish PA training programmes. As of late 2012, there were approximately 150 PAs working in Britain,5 practising in 20 different specialties in more than 25 acute National Health Service (NHS) trusts, as well as in primary care.6 In mid-2013, the profession changed its name from ‘physician assistant’ to ‘physician associate’ to avoid confusion with some other health professions in the UK that use the first title.

A key strength of the role of PAs is that they work under the supervision of doctors. Both the PA and the supervisor understand the PA's current skills and competencies, and know that the PA will seek consultation appropriately. Through supervision and continuing professional development the PA's skills are further developed and focused towards the needs of the employer. The level of satisfaction that supervising doctors have with their PAs has been assessed previously in the English and Scottish pilot projects, where doctors were generally satisfied with their role and performance. However, these pilot projects assessed US-trained PAs and were conducted in the mid-2000s. Although doctor satisfaction with the PA role has been assessed within specific specialties,7 no recent research has attempted to systematically assess doctors’ level of satisfaction with PAs across various specialties and settings. In addition, because the PA profession currently lacks statutory regulation, we queried doctors about the impact of voluntary regulation of the PA profession. Therefore, in autumn 2012 the authors designed a survey to be sent to all known PA supervisors across the UK.

Methods

The survey was designed to collect descriptive data on the responding doctors themselves, the perceived benefits and challenges of the role of PAs from the doctors’ and patients’ perspectives, and the impact of the PA profession being under voluntary rather than statutory regulation. The survey did not collect identifiable personal information on PAs or PA supervisors. It was made clear to the respondents that the survey was intended to collect data on their general experiences with the PA role and was not an evaluation of individual PAs. The questionnaire was pre-tested with PA employers and the survey improved based on their feedback.

Our goal was to collect data from every consultant-level doctor working with a PA in the UK. To recruit study participants, we sent a link to the online data collector to all doctors for whom the UK Association of Physician Associates (UKAPA) had contact details. In addition, the UKAPA emailed a link to the survey to all PAs for whom they had contact information and requested that they forward the link to doctors with whom they work. PAs were reassured that the survey was not an evaluation of an individual's work. The online data collector was open from October to December 2012. Three reminder emails were sent to both doctors and PAs to improve the response rate. It is difficult to estimate the number of doctors working with PAs because one doctor may supervise several PAs, and one PA may be supervised by several doctors. As there were approximately 150 practising PAs in the UK in late 2012, the authors estimated, for the purposes of this survey, that there are roughly 150 supervising doctors as well.

Results

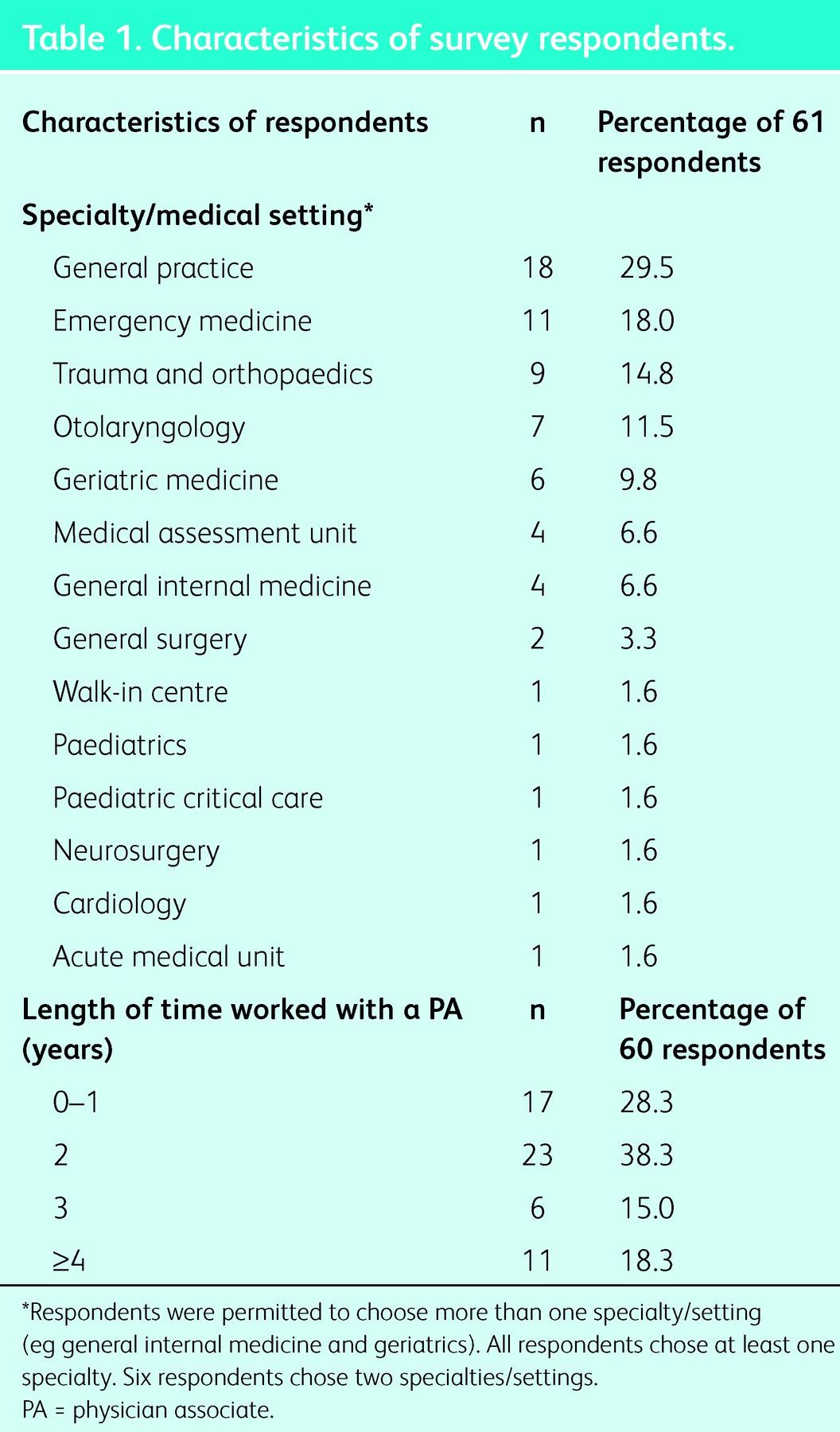

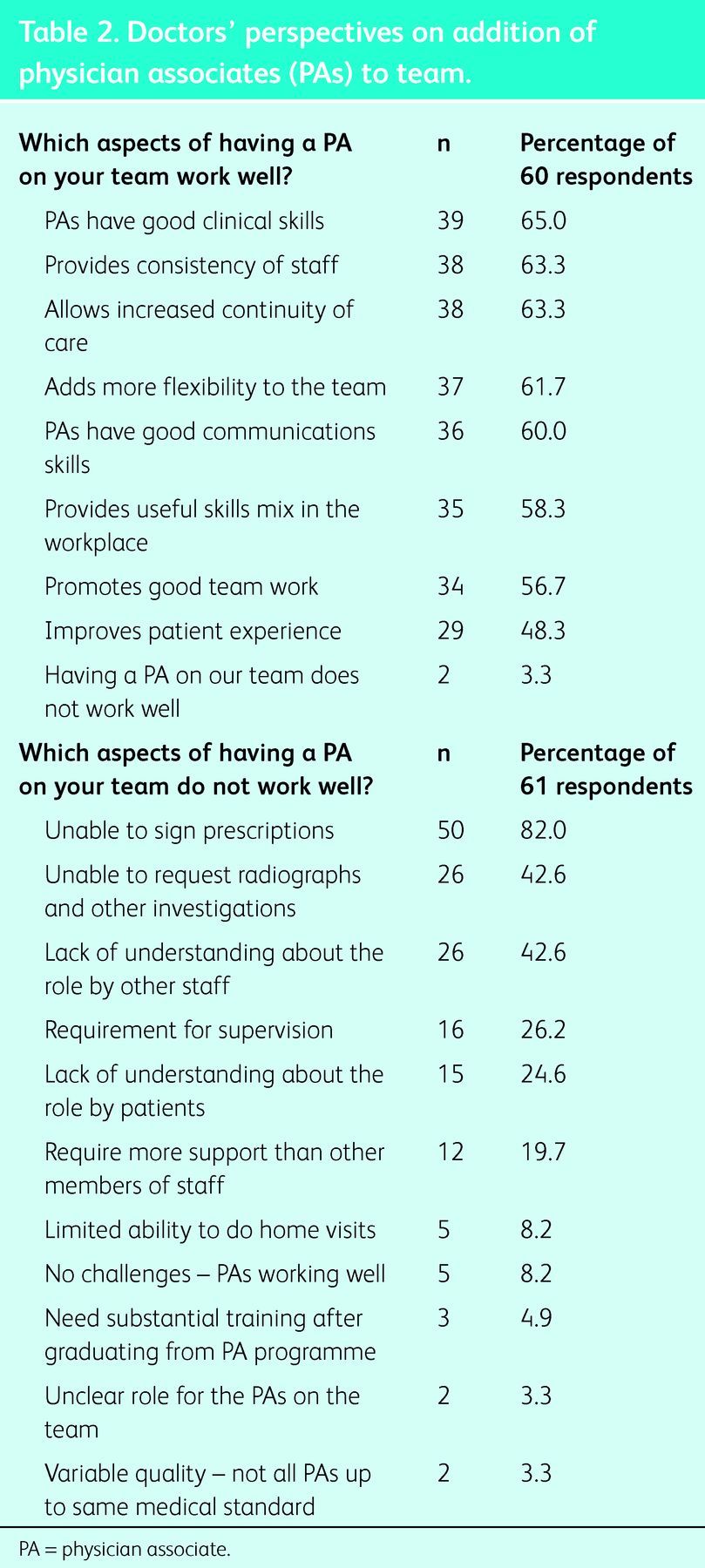

Sixty-one doctors completed the survey (40.7%), representing 14 specialties or medical settings. On average, these doctors had worked with a PA for 2 years (range 2 months to 8 years) (Table 1). When asked which aspects of having a PA on the team worked well, more than 50% of the respondents indicated that they felt that PAs have good clinical and communication skills, and that they improve team flexibility and the continuity of care provided (Table 2). Just under half felt that having a PA on the team improved the patient experience and having PAs promoted good teamwork. Two respondents (3.3%) felt that having a PA on the team did not work well. In one of these cases, the respondent indicated that a practice manager had hired a PA as a cost-saving measure without consulting the doctors with whom the PA would work. The other respondent did not indicate why she or he felt having a PA on the team did not work well.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents.

Table 2.

Doctors’ perspectives on addition of physician associates (PAs) to team.

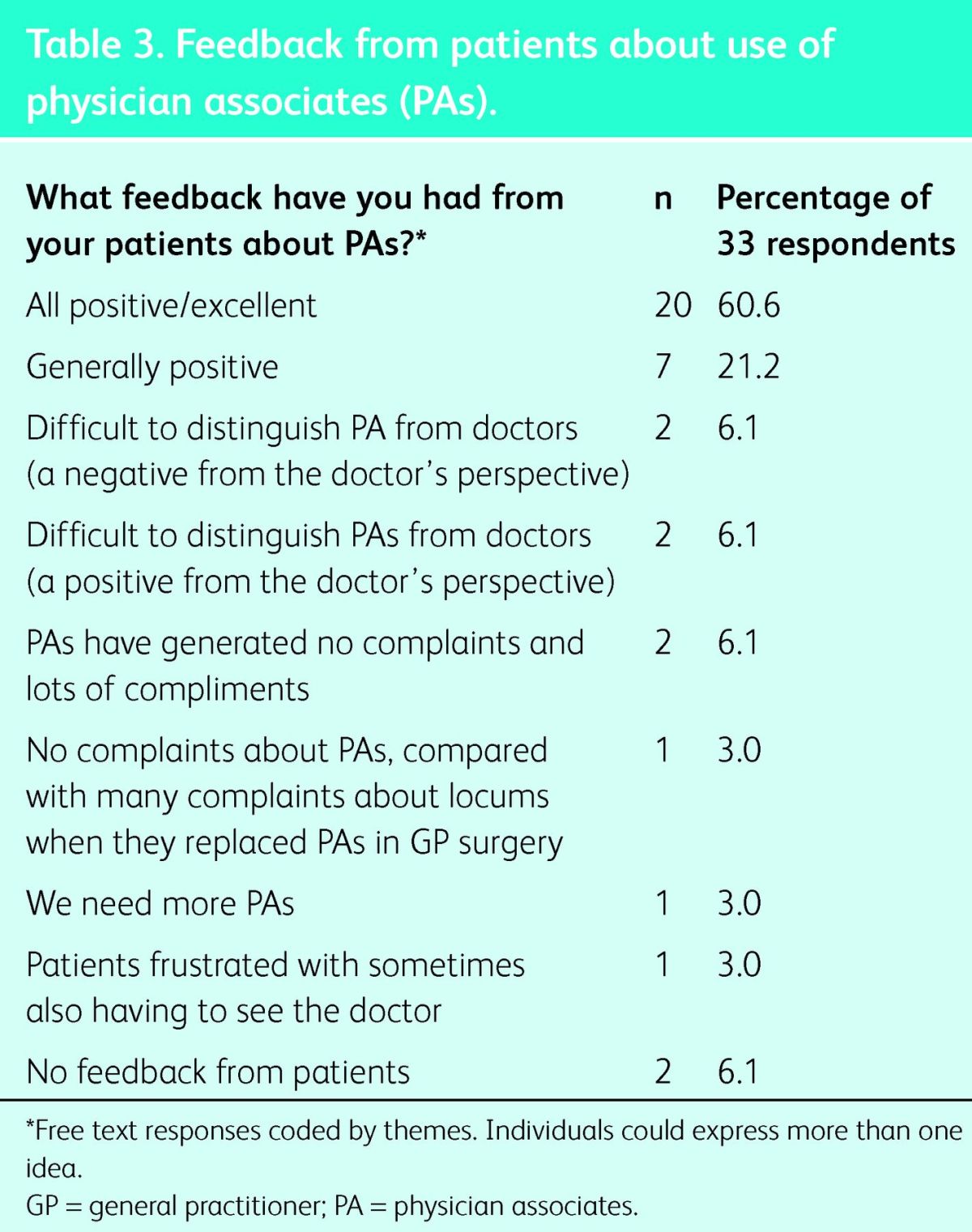

Doctors were also asked to comment on which aspects of having a PA on the team did not work well (Table 2). By far the largest majority of the doctors indicated that the current legal restrictions that prohibit PAs from prescribing limited their effectiveness (28%). Almost half of the doctors cited limitations on requesting radiologic tests and other investigations, and lack of understanding of the role of PAs as difficulties. Roughly one-quarter of the respondents believed that the requirement for physician supervision and greater need of supervision for PAs than for other staff are also limitations to the role. Less than 10% of the doctors cited other limitations (see Table 2). Doctors reported that their patients typically expressed satisfaction with the role of PAs, with 27/33 doctors reporting that the responses to PAs were either ‘all positive’ or ‘generally positive’ (Table 3).

Table 3.

Feedback from patients about use of physician associates (PAs).

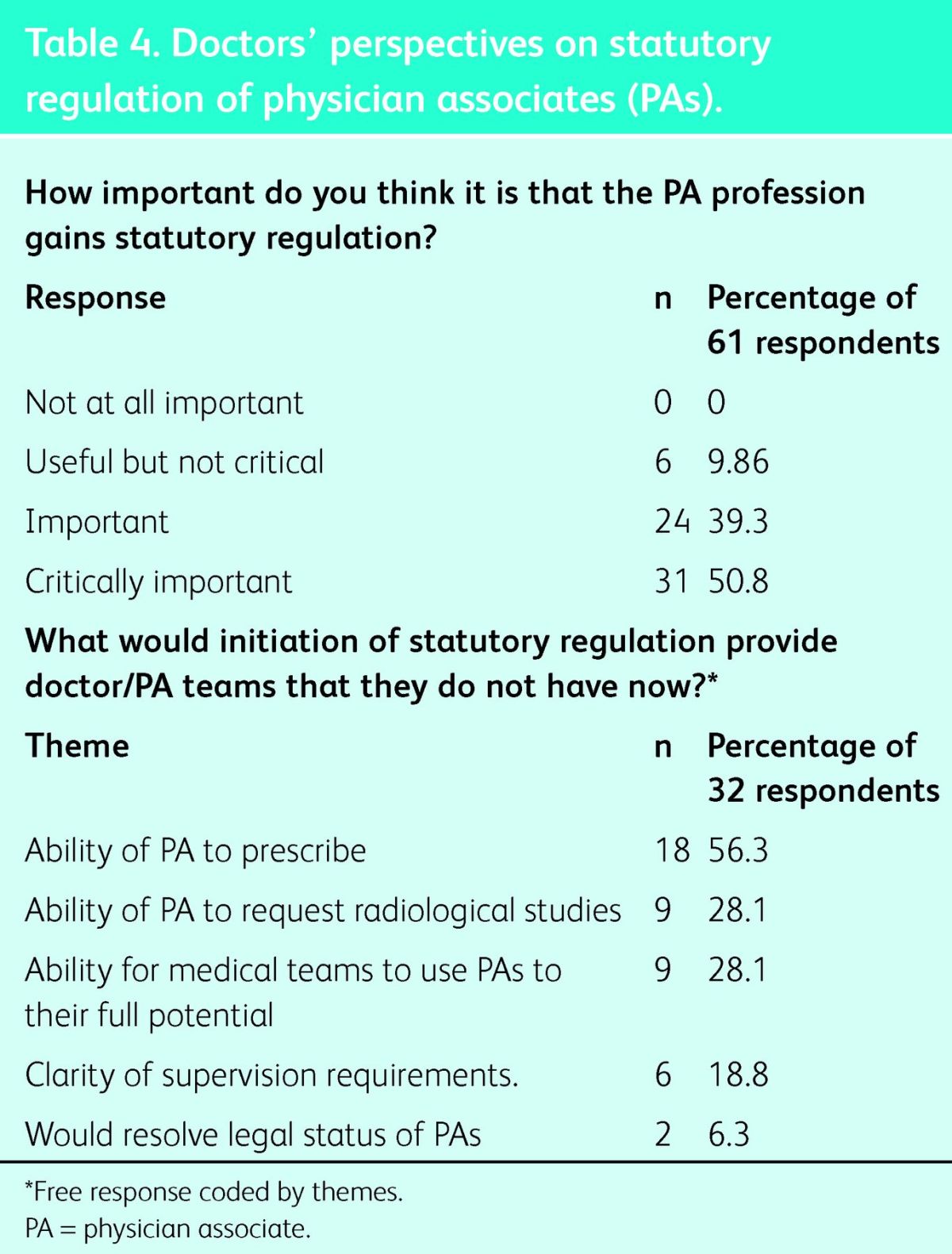

Doctors were surveyed about their perception of the need for statutory regulation of PAs (Table 4). More than 90% of doctors felt that statutory regulation was important. No respondents felt that it was unimportant, and less than 10% felt that regulation would be ‘useful, but not critical’. Doctors were then asked how initiation of statutory regulation would impact on doctor/PA teams. Respondents were allowed to answer with free text and 32 chose to do so. Responses were coded by themes. Most felt that PAs would be able to prescribe if statutory regulation were achieved. Nine respondents (28.1%) believed that statutory regulation would allow PAs to use their full potential within the team and that they should be allowed to order radiological investigations. A smaller number of doctors believed that statutory regulation would clarify supervision requirements and the legal status of PAs.

Table 4.

Doctors’ perspectives on statutory regulation of physician associates (PAs).

Discussion

In this survey of British doctors who currently work with PAs, doctors were generally satisfied with their role. These results are consonant with previous research performed using more limited groups of doctors.2,3,7 Most doctors surveyed believed that the PAs possessed good clinical and communication skills and offered a beneficial continuity to practices and patients. Doctors also reported that patient feedback about the role of PAs was typically positive. The biggest limitations to this role, identified by doctors, were limitations imposed by legal restrictions on PA practice, not those resulting from lack of training or poor-quality PAs. Doctors strongly support the development of statutory regulation for PAs and believe that the initiation of regulation would allow them to perform a broader range of medical duties, which would benefit doctors and patients alike.

The legal aspects of PA practice are worth further discussion. Despite specific training in pharmacology and radiology, PAs cannot prescribe and cannot request tests that use ionising radiation, due in part to the lack of statutory regulation. It is notable in this survey that doctors did not express concerns about the safety of allowing their PAs to prescribe or request investigations. They were more concerned that doctor time was being used to sign prescriptions and request investigations on behalf of PAs. Doctors believed that granting PAs statutory regulation would allow them to then prescribe under existing non-medical prescriber regulations and could eventually allow PAs to request radiological investigations. Doctors also felt that the current unregulated status of PAs potentially put them and their PAs in legal jeopardy, so the legal status of PAs should be resolved as soon as possible. Despite the recommendations of the Francis Report on excess deaths at the Mid-Staffordshire Foundation Trust7 that all hands-on healthcare personnel be regulated, the current government still supports only a voluntary register for PAs.

Aside from legal factors, the biggest source of dissatisfaction among doctors with the role of PAs is the heterogeneity of PA training and unclear role expectations. PA training programmes have had substantial variability in institutional support, medical education expertise and student admissions criteria, which has led to differences in the quality of PA training. In addition, until recently, PA students have not had graduate PAs to emulate as they seek to develop their expertise and roles. Similar heterogeneity was seen at the start of the PA profession in the USA.9,10 Rigorous application of the Competence and Curriculum Framework for the PA, development of a PA education regulatory body, as well as continued administration of the PA national examination should hopefully decrease PA variability. Role expectations should also be clarified over time as legal questions are settled and the model of the ‘UK PA’ is established by experience.

Doctors expressed varying beliefs about the perception of PAs by patients. Some doctors made comments to indicate that they believed patients could not tell whether the PA was a doctor. Some doctors thought this inability to distinguish was positive and reflected the competence of PAs. An equal number of doctors thought this difficulty was dangerous and negatively reflected on the PAs and the medical team. Further research is needed to understand the nuances of how the role of PAs is presented to patients and how patients perceive it.

This current study has several limitations. First, without regulation, it is difficult to know how many doctors currently supervise PAs. For the purposes of this study, the authors assumed a one-to-one ratio of doctors to PAs. The response rate of 40.7%, given this assumption, is reasonable, but not an optimal rate for return of surveys. Respondents were well distributed among the specialties in which PAs practise, although otolaryngology was somewhat over-represented. Second, it is possible that doctors who are satisfied may have been more likely to respond to the survey because it was not distributed in a way that obligated all recipients to respond. Doctors may have felt that the survey responses from which they were allowed to choose did not represent their feelings accurately; however, the authors allowed unlimited free text responses and coded these in an attempt to allow doctors to express their true concerns without a filter. Finally, it makes some intuitive sense that doctors who are happy with the role of PAs are likely to hire them. We cannot ascertain from this survey whether there are doctors who have recruited PAs only to fire them after a time because they are dissatisfied with individual PAs or their role. Doctors who do not currently work with PAs were not included in this analysis.

Conclusion

This is the first national survey of doctors in a wide range of specialties who have experience working directly with PAs. As demonstrated in previous studies, doctors who work with PAs on a regular basis are pleased with the role. The feedback that doctors receive from patients about PAs is generally positive. Doctors are most concerned that they cannot use PAs to their full potential due to current legal limitations. They strongly support statutory regulation for PAs as a necessary component for the most effective use of these practitioners within the NHS.

References

- 1.Ritsema TS, Paterson KE. Physician assistants in the United Kingdom: an initial profile of the profession. JAAPA Off J Am Acad Physician Assist 2011;24:60. 10.1097/01720610-201110000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodin J, McLeod H, McManus R, Jelphs K. Evaluation of US-trained Physician Assistants working in the NHS in England. Birmingham: Department of Primary Care and General Practice, University of Birmingham, 2005. www.bhamlive1.bham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/HSMC/publications/2005/Evaluation-of-US-trained-Physician-Assistants.pdf [Accessed 6 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer J, Currie M, Hyman J, et al. Evaluation of physician assistants in National Health Service Scotland. Scott Med J 2011;56:130–4. 10.1258/smj.2011.011109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health The Competence and Curriculum Framework for the Physician Assistant. London: DH, 2006. www.ukiubpae.sgul.ac.uk/competence-and-curriculum-framework/PA%20-%20Competence%20and%20Curriculum%20Framework%20-%20Sept%2006.pdf [Accessed 6 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UK Association of Physician Associates FAQs. www.ukapa.co.uk/general-public/faqs/index.html [Accessed 8 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross N, Parle J, Begg P, Kuhns D. The case for the physician assistant. Clin Med 2012;12:200–6. 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-3-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drennan V, Levenson R, Halter M, Tye C. Physician assistants in English general practice: a qualitative study of employers’ viewpoints. J Health Serv Res Policy 2011;16:75–80. 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.010061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Inquiry Independent Inquiry into care provided by Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust January 2005–March 2009. London: The Stationery Office, 2010. www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/key-documents [Accessed 24 January 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadler A, Sadler B, Bliss A. The Physician's Assistant: Today and tomorrow, 2nd edn. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Co, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cawley J, Hooker R, Asprey D. Development of the profession. In: Physician Assistant: Policy and practice. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Co, 2010:48–9. [Google Scholar]