Abstract

Many people with dementia are admitted to general hospitals, yet doctors feel ill-prepared to manage them. Problems are often multiple and complex. In many cases, dementia is complicated by delirium. Medical assessment must be meticulous and requires collateral history taking, mental state examination and cognitive function testing. Hospital environments can be provocative, and the way staff interact with people with dementia can increase distress. Difficult behaviours usually represent unmet needs. The right approach by (all) staff can reduce this, including special efforts to establish reassuring, comforting relationships with patients. Try to see situations from the perspective of the person with dementia. Skilled communication is vital and family carers should be kept informed and involved. People with dementia are prone to side effects of prescribed drugs. Antipsychotic drugs are rarely the answer to difficult behaviours, but may be used in cases of psychosis or severe distress.

Key Words: communication skills, delirium, dementia, geriatric medicine, hospital care, person-centred dementia care

Introduction

The National Dementia Strategy calls for improvements in the general hospital care of people with dementia and a better-prepared workforce.1 This article aims to identify why difficulties occur and offer practical advice on managing people with dementia in hospital. The evidence base is weak, so the style deliberately polemical. Much of the content is based on experience in developing and working on an acute care medical and mental health unit in a general hospital.2 Readers seeking an account of definition (Box 1), sub-types (Box 2), pathology, diagnostic work-up, cognitive enhancing drug treatment and community management are directed elsewhere.3

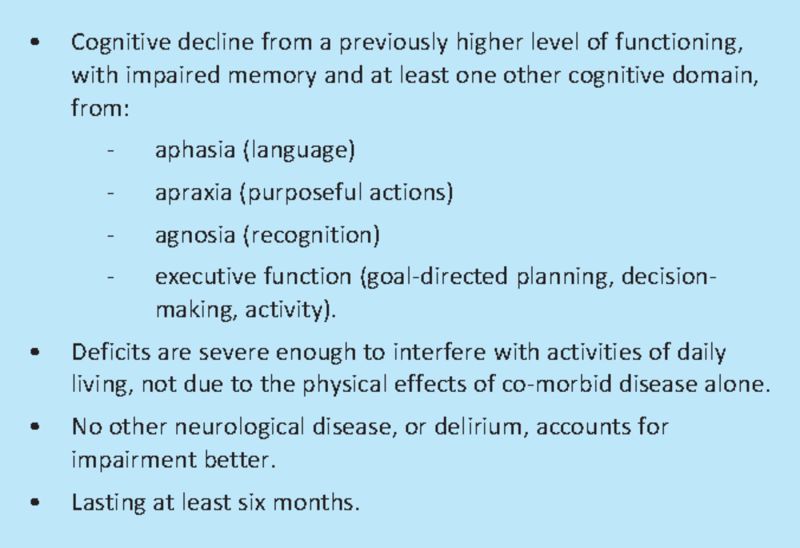

Box 1. General diagnostic criteria for dementia. Adapted from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, DSM–IV, American Psychiatric Association.

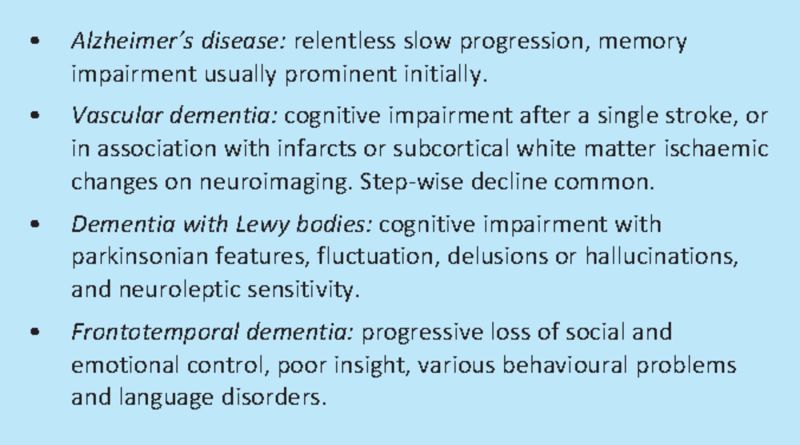

Box 2. Sub-types of dementia.

Who cares?

Forty per cent of acute general medical admissions over the age of 70 have dementia. Cognitive impairment is evident in 60% of patients on acute geriatric medical wards, and in 55% of patients with hip fracture. Overall, 25% of hospital beds accommodate someone with dementia.4–8

Most are admitted for legitimate medical illness or injury requiring hospital treatment. Indeed, on average, illness severity is greater in people with dementia than without.5 Hospital presentations also include sudden worsening of confusion or dependency, or functional crisis such as falls, which may or may not have an acute physical illness underlying them. The skills of the general physician are required to diagnose or exclude physical illness. Family members and carers of people with dementia are frequently dissatisfied with their experience of hospital care, including staff not recognising or understanding dementia, lack of activity and social interaction, inadequate involvement in decision making and perceived lack of dignity and respect.7 Care of people with dementia often features in scandals, and is a frequent focus of complaints.9–10

Hospital stay for people with dementia is longer than for those with similar primary diagnoses but without co-morbid dementia.5–6 Admission can be very prolonged: in England 10% of people with dementia stay in hospital for more than 50 days.11

Half of people with dementia in the community, and half of those admitted to hospital, are undiagnosed.1,5,8 The National Dementia Strategy argues for a substantial effort to diagnose more and to make diagnoses earlier. In future, patients who carry a diagnostic label may only have mild or minimally disabling dementia.

Central to efforts to improve hospital care has to be an ethos that values people with dementia and those who care for them, rather than an attitude that ‘they should not be here’.

Dementia in the acute hospital is different

Dementia in the acute hospital is different from that seen in the community and in care homes. In hospital, two-thirds of people with dementia also have evidence of delirium.12 Alzheimer's disease predominates in the community, but vascular dementia is most common in hospital (the steps of the ‘stepwise deterioration’ of vascular dementia include a sudden worsening of cognition, that needs to be distinguished from delirium, and may be associated with falls, immobility, swallowing difficulties or incontinence). Physical disability, dependency and mental health symptoms are much more severe in hospital: half need help eating, or transferring from bed to chair, a third are awake at night, 15% have hallucinations or delusions.8

Why dementia is difficult

Healthcare staff report that they struggle with managing the complex needs of people with dementia.7 Problems start with diagnosis. History taking almost always requires collateral information. Poor understanding, or misinterpretation, leading to restlessness or poor co-operation, can hinder examination and investigation.

Mental state examination is a basic medical competency but this is unfamiliar territory for physicians and is rarely done thoroughly. Problems such as hallucinations, delusions, depression and anxiety fail to be elicited. Assessment of speech is more familiar, but systematic examination and documentation of communication ability in the context of cognitive impairment is rare. Routine, brief cognitive assessment (eg using the 10-point abbreviated mental test13) should be performed at admission on all older patients, but is achieved in only about half. If abnormal, this should be followed up, using the 30-point mini-mental state examination (MMSE),14 and by taking a collateral cognitive history.

People with dementia increasingly depend on familiarity and routines. Hospital admission disrupts these. For this reason, signs of dementia are sometimes first recognised during hospital admission. Previous character traits (such as short temper) can be disinhibited in dementia. But people with dementia are not usually aggressive, difficult, wilful or attention-seeking by nature. They respond with these behaviours if they are overwhelmed by the circumstances in which they find themselves: uncomprehending, threatened, scared in provocative, busy, crowded, noisy environments. Or they may become passive and withdrawn. Staff responses based on confrontation, admonition or drugs, makes matters worse.

Discharge planning needs extra care and multidisciplinary expertise. Risk assessment is important, although the term ‘risk enablement’ has been introduced to highlight the dangers of diminishing quality of life through restrictions aimed at promoting ‘safety’.15

The problems of people with dementia take longer to solve. Assessment, recovery, rehabilitation and discharge planning are all slower, which sits uncomfortably with contemporary hospital culture.

Understanding delirium

Not all ‘confusion’ is dementia. Mimics include stroke with aphasia, deafness or functional psychosis. The other main cause of cognitive impairment is delirium. Delirium is a syndrome of impairment of cognition and attention or arousal, caused by a physical illness.3

The key feature is change in cognition, either of new onset, or a worsening of prior confusion. Logical thought and reasoning are more affected than orientation. Families may report a change in ‘personality’ or behaviour. About half the delirium seen in general hospitals complicates prior dementia. However, establishing this is more difficult than might be imagined. The prior dementia may have been undiagnosed, and pre-existing cognitive symptoms may have been unrecognised by family, or ‘compensated’ by additional help. An unfamiliar hospital environment can cause behaviour change even when there is no delirium.

Other features include inattention or abnormal conscious level. The patient may be distractible, drowsy, hypervigilent or apathetic, and this may change with time. Variation means a single assessment can be misleading. Visual hallucinations, paranoid delusions, motor restlessness, agitation or retardation, and sleep disturbance are common. These clinical signs are not well-detected by physicians or general nurses.

Any medical illness can result in delirium, including infections, drug initiation and withdrawal, metabolic and hypoxic disorders and stroke. A proportion (about 15%) of cases of clinically convincing delirium has no adequate medical explanation. Multiple factors are implicated in over half.

It gets better in most cases, although recovery may be slow: 40% persists at two weeks, 33% at a month, 25% at three months. About 20% never recovers.16 This means that critical decisions (eg about moving to a care home) may have to wait, and identifying a venue to wait in can be difficult.

Management comprises identifying and treating the cause, waiting for recovery, and trying to prevent complications. Short-course, low-dose anti-psychotic drugs may have specific preventative or delirium-shortening properties, but this remains controversial.3,17,18

First do no harm

Many family carers are convinced that hospital care causes deterioration in people with dementia.7 Disentangling the effects on function of acute or progressive illness, or suboptimal care, is difficult. At the very minimum, hospitals should try to minimise distress, loss of abilities and wrong decisions being made. Unduly prolonged hospital stays must be avoided and where effective non-hospital alternatives are available they should be used.

The problem is that if treated in the wrong way, people with dementia are easily distressed, suffer complications and may be unnecessarily disabled. The impact of dementia is partly due to neurological impairment, but is also influenced by personality, biography, co-morbid physical and mental health, and by the social environment.19 Some of this is open to intervention.

The medical contribution to solving problems is to make diagnoses correctly and treat them optimally. Given the mix of acute and chronic disabling diseases this can be difficult, and additional consideration of function, social situation, mental health and environment is needed. Opportunities for attempts at rehabilitation must be recognised, including so-called ‘adaptive’ as well as ‘restorative’ approaches–some functions can be supported even when it is impossible to regain independence.20

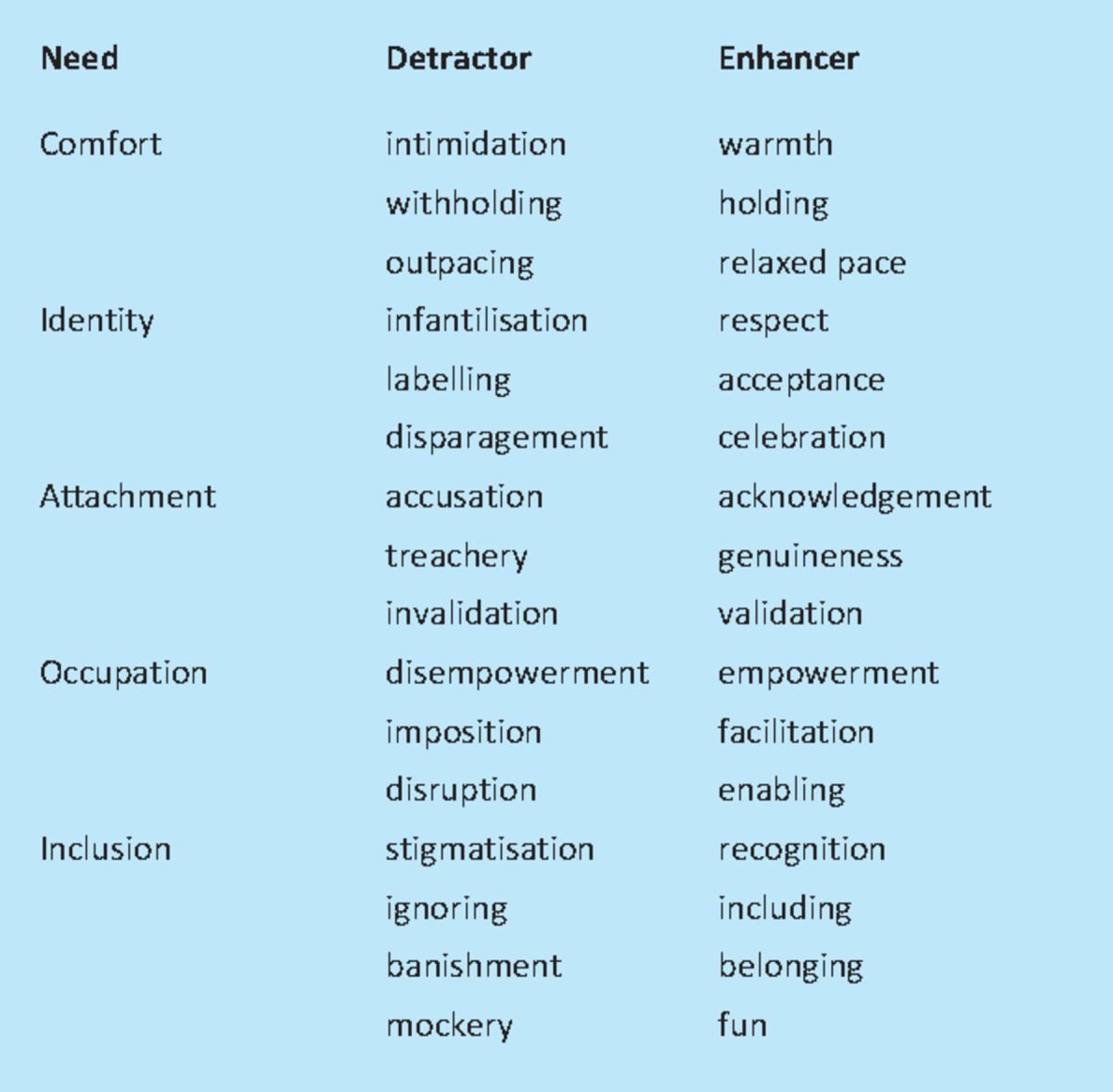

The social environment is about relationships. Because of problems such as memory loss or communication difficulties, a person with dementia needs help in making and sustaining relationships (an ‘enhanced’ social environment). This means healthcare professionals have to be friendly and helpful, without expecting reciprocity. What often happens is that (unintentionally) people do the opposite–they go too fast, they overwhelm, accuse, exclude or ignore, and may punish, infantilise or tell lies (Table 1). The term ‘malignant social psychology’ is used to describe this. The effect is to make the experience of dementia more difficult or frightening, and this can express itself as withdrawal, anxiety or difficult behaviour. The quiet patient may be as distressed and harmed as a noisy one.19,21

Table 1.

Malignant social psychology. This is what people with dementia experience in hospital because of the way people interact with them. Each negative feature (‘personal detractor’) has a corresponding positive alternative (‘personal enhancer’), which improves experience and reduces distress. Adapted with permission of Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London and Philadelphia.21

Making hospital care easier for a person with dementia

The philosophy of ‘person-centred dementia care’ is considered best practice,21 but has to be adapted for the particular circumstances of the acute hospital.2 All healthcare team members must contribute.

Try to see the world through the eyes of the person with dementia. Make no assumption about what is understood or remembered. Hearing and visual impairments, and other physical impairments, can make confusion appear worse. Situations may be misinterpreted, often in terms of memories from the past (eg being at work or having childcare responsibilities). Responses will vary with personality and life history. Knowing about this from a personal profile can help (such as the Alzheimer's Society's ‘This is me’ document).

Medical, nursing and interpersonal care must be individualised. Failure to see the ‘whole person’ is a major source of resentment for family carers (exemplified by statements such as ‘we are here to deal with the pneumonia not the dementia’). Identify and make use of retained abilities. ‘Occupational profiling’ (by occupational therapists) can help by finding activities that the person with dementia can do and succeed at.22

Providing purposeful activity can help to maintain abilities and represent a diversion to prevent boredom and restlessness. Opportunities to do this are few in acute hospitals, and have become fewer as hospitals become more brutally focused on sole management of acute medical problems. However, unregistered care assistants (under the supervision of occupational therapists) can deliver activities to those who are well enough. Mundane everyday tasks, including meals, can become an ‘activity’. Getting patients up and dressed enhances dignity and a sense of normality.

Familiarity and routine should be preserved as far as possible. This can mean using personal possessions, family members to help with care or sitting, understanding what is liked and disliked, and how to cope with agitation or distress. Minimise ward or bed moves and try to keep staff consistent.

The physical environment in hospital can be bland and disorientating. Wards and bays look the same. There are few orientation cues or points of visual interest. Wards are noisy (radios, staff, call buzzers and equipment alarms) and crowded (so one distressed patient will disturb a whole bay). Agnosia can mean that toilets are not recognised. Colour coding bays, using large pictorial signs, personalising bed spaces (with photographs, cards or small low-value personal possessions), clocks and orientation boards can all help, including reducing wandering and interfering with other peoples' belongings. Family carers have a special role in the lives of many people with dementia, being hands-on carers, but also care coordinators and advocates, and social and emotional supporters. They will often be stressed and tired in the run up to a hospital admission.

Under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 family carers have a right of consultation over decisions about a person lacking capacity. Some (with a health and welfare lasting power of attorney or court-appointed deputies) will have legal authority over decisions. Proactive communication is vital (you seek them out, do not wait for them to ask you). You need information, about the history of the presenting complaint, but also about cognition and changes that might indicate super-added delirium, function, services and coping resources, as well as personal profile data. They need to be kept informed and involved. But note that caring relationships vary: about 10% of people admitted to hospital with dementia have no contactable carer,8 and many will be non-co-residents offering more distant oversight than hands-on care. Carers may come as networks or teams, and may not communicate or get on well with each other.

Communication with a person with dementia

Involve the person in discussion. Levels of communication will vary greatly. People with dementia are often able to say how they feel now (current symptoms) but are less able to gauge changes over time, remember past symptoms, or use abstract ideas to understand or describe what might be happening to them. Some points of fact will have to be obtained or confirmed from others.

Use the rules familiar in communicating with someone with aphasia. Speak at a normal rate, but keep language simple (no jargon or double negatives) and sentences short, and repeat or re-phrase if not understood. Tone of voice can be more important than content. Intensive questioning can be overwhelming; yes/no or multiple choice questions may work best. Use facilitation (gesture, pictures, writing) and interpretation (check for understanding, repeat).

Body language is important. Speak from the level of the patient (crouch or sit) and from the front. Make eye contact. Always be calm, and friendly, smile. Use touch (handshake, hand-holding, hand on shoulder).

Avoid confrontation, contradiction or humiliation. Do not disabuse someone of an evident untruth (‘my children are waiting at home’), but try to distract or investigate the emotional underpinning of the concern (‘tell me about your children’).

Dealing with behavioural crises

The glib answer is to prevent crises, not deal with them after they occur. Person-centred care aims to minimise difficult behaviours by avoiding confrontation, communicating well, providing activity, distraction and comfort.

If one patient attacks another, they must be separated. Otherwise avoid confrontation at all costs. De-escalation methods, or moving to a quiet room, for talk or occupation, usually work even for severe distress, but are time consuming, and require skilled nursing (along with cups of tea, television, a walk or a bath).24

Not all difficult behaviours are preventable, for example, someone who shouts out continually, or stands up without help despite being unsafe to do so. One-to-one nursing care may be the only solution. Given the scarcity of this resource, we need to be confident about identifying when this is the only acceptable approach. Relatives may be able to help.

Some behaviour simply has to be tolerated. Wandering is an example. You can try to understand it, and try to keep it safe, but rarely can you stop it. Night-time disturbance is common, minimised by trying to keep patients active by day, but difficult to manage. Short acting hypnotics (eg temazepam) may help, while being wary of the increased risk of falls. Agitation and aggression may be reduced, but not always abolished.

Aggression during nursing care tasks can be minimised by talking through procedures, or withdrawing and trying again later (there is usually no real need to get washed or shaved first thing in the morning). Sometimes this is not an option (eg a soiled incontinence pad that needs changing, or inserting a cannula), and brief passive physical restraint is probably the best option.

A word about drugs

Many drugs can cause delirium, including any with anti-cholinergic effects or side-effects, opiates, and psychotropic drugs. Minimise their use. Drugs rarely, but not never, help in the management of behaviour or other non-cognitive symptoms.3,18,24,25 There is little evidence for the effectiveness of any antidepressant, but they may be tried in emotional lability, severe anxiety, or if mood is very low.

Benzodiazepines should be avoided in delirium (other than alcohol withdrawal), and have little role in dementia, although some patients on longstanding benzodiazepines may be best left on them during an acute admission if they are not causing immediate problems. They may be used as an adjunct in rapid tranquilisation regimens and occasionally in dementia with Lewy bodies.

Reducing antipsychotic drug use is a major policy imperative.25 The main justification for their use is treating psychosis, immediate grave risk of physical harm or severe distress. Risperidone has some effect in reducing ‘aggressive agitation’. Antipsychotic drugs (including atypicals) have extrapyramidal side effects, increase falls, mortality and the incidence of heart attack and stroke. If you feel constrained to try them, keep doses low, review scrupulously for effectiveness, and try to discontinue after three months or so. Antipsychotics are especially poorly tolerated in dementia with Lewy bodies (cholinesterase inhibitors or low-dose quetiapine being the drugs of choice in this case). Increasingly, doctors will be expected to discuss explicitly the purpose, benefits, risks and uncertainties of antipsychotic drug use with family carers before prescription.

Cholinesterase inhibitors improve cognition and function in Alzheimer's disease by a small amount (one MMSE point on average), but about 15% are ‘super-responders’ (improving four or more MMSE points).3,24 They should be initiated in settings where diagnostic subtyping, and review for effects and side effects, may be undertaken (usually memory clinics). If there is no benefit they should be stopped.

Conclusion

Acute hospitals are not well configured for dealing with people with dementia, and staff, including doctors, are ill-prepared for dealing with the challenges they bring. This is inequitable, intolerable and possibly illegal. Few hospital disciplines can avoid looking after some patients who are confused. There is an expertise, and dealing with it well makes life easier and less stressful for patients, carers and staff. Care is multi-professional, but doctors must understand their specific role (primarily diagnosis, information giving and drug treatment) and deliver it well.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Simon Hammond, Catherine Russell, Annie Ramsay, Amrit Chowdhary, John Morrant and Fiona Kearney for suggestions, and Jonathan Waite, Davina Porock, Ian Morton, Sarah Goldberg, Nikki King, Gerry Edwards and Louise Howe for teaching me how to do this.

References

- 1.Department of Health. Living well with dementia: a national dementia strategy 2009London: DH [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harwood RH, Porock D, King N, et al. November 2010. Development of a specialist medical and mental health unit for older people in an acute general hospital. University of Nottingham Medical Crises in Older People discussion paper series Issue 5. www.nottingham.ac.uk/mcop/index.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waite J, Harwood RH, Morton IR, Connelly DJ.Dementia care; a practical manual 2008Oxford: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of Psychiatrists. Who cares wins 2005London: RCPsych [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sampson EL, Blanchard MR, Jones L, Tookman A, King M. Dementia in the acute hospital: prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. Brit J Psych 2009; 195: 61–6 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes J, House A. Psychiatric illness predicts poor outcome after surgery for hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. Psychol Med 2000; 30: 921–9 10.1017/S0033291799002548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alzheimer's Society. Counting the cost 2009London: Alzheimer's Society [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg SE, Whittamore K, Harwood RH, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems amongst older adults admitted as an emergency to a general hospital. Age Ageing 2012; 41: 80–6(epub1 September 2011:doi10.1093/ageing/afr/106). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Healthcare Commission. Investigation into Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust 2009London: Healthcare Commission; www.cqc.org.uk/_db/_documents/Investigation_into_Mid_Staffordshire_NHS_Foundation_Trust.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parliamentary and Health Services Ombudsman Report of the Health Service Ombudsman on ten investigations into NHS care of older people. Care and compassion? 2011London: TSO [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal College of Psychiatrists. National audit of dementia in general hospitals. Interim report 2011London: RCPsych [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SV. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 1723–32 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodkinson HM. Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing 1972; 1: 233–8 10.1093/ageing/1.4.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psych Res 1975; 12: 189–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manthorpe J, Moriaty J.Nothing ventured nothing gained. Risk guidance for people with dementia 2010London: Department of Health; www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_121492. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cole MG, Ciampi A, Belzile E, Zhong L. Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: a systematic review of frequency and prognosis. Age Ageing 2009; 38: 19–26 10.1093/ageing/afn253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalisvaart KJ, de Jonghe JF, Bogaards MJ, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis for elderly hip-surgery patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 1658–66 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Delirium: diagnosis, prevention and management 2010London: NICE; www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13060/49909/49909.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitwood T.Dementia reconsidered. The person comes first 1997Buckingham: Open University Press [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gladman JRF, Jones RG, Radford K, Walker E, Rothera I. Qualitative evaluation of a specialist community service for people with dementia: specialist dementia services are feasible, but can they be sustained? Age Ageing 2007; 36: 171–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooker D.Person centred dementia care: making services better 2006London: Jessica Kingsley; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pool J. The Pool activity level (PAL) instrument for occupational profiling 2008London: Jessica Kingsley [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Violence. The short-term management of disturbed/ τνɛιταπ−νι νιρυοιϖαηɛβ τνɛλοιϖ.στνɛμτραπɛδ ψχνɛγρɛμɛ δνα σγνιττɛσ χιρταιηχψσπ 2005London: NICE; 33–6www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/10964/29715/29715.pdfViolence. The short-term management of disturbed/τν& [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care 2006London: NICE; www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/10998/30318/30318.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banerjee S.The use of antipsychotic medication for people with dementia: time for action 2009London: Dementia for hospital physicians Department of Health; www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_108302.pdf [Google Scholar]