Abstract

Medical professionalism has been notoriously difficult to define and remains poorly understood. Because of this, graduates often have contrasting views on how it is best taught. These views should be considered and incorporated into teaching methods in order to enhance learning and development. Over a six-month consecutive period doctors and medical students in County Durham and Darlington Foundation Trust completed a questionnaire asking them to define professionalism, state where they felt they had learnt about professionalism and how important they feel professionalism is to them. They were also asked to identify how they felt teaching about professionalism was best delivered from a selection of educational resources. The findings highlight major differences between how the material is taught and how students and graduates feel they learn best about professionalism and more research into this field is needed.

Key Words: education, medical, professionalism, teaching

Introduction

Medical professionalism has been notoriously difficult to define and remains poorly understood. In 2005 the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) published the results of a working party that aimed to conceptualise modern medical professionalism and provide a definition that could be universally recognised.1 They acknowledged that social and political factors, together with the advancement of medical science, have reshaped attitudes and expectations, both of the public and of doctors.

Using a range of evidence including focus groups, questionnaires, witness interviews and peer-reviewed literature, they defined a concept of medical professionalism that encompasses behaviours and values that doctors should exhibit as well as highlighting the role of knowledge, skills and judgement. The definition identifies various characteristics, such as respect, responsibility and accountability, and states that doctors should commit to integrity, compassion, altruism, continuous improvement, excellence and working in partnership with members of the wider healthcare team in their day-to-day practice.

Other definitions proposed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education2 and Epstein and Hundert3 incorporate many of the same characteristics but emphasise issues such as protecting confidentiality and displaying sensitivity towards different cultures, genders and disability. All of the existing definitions read similar to the list of key qualities that are outlined in the General Medical Council's (GMC) Duties of a good doctor4 and the expansion of the role of the GMC from undergraduate support to regulation of all medical education has made teachers increasingly aware of how professionalism is taught.

Historically the development of professionalism relied on implicit learning from respected role models, a method that depended heavily on the presence of a homogeneous society sharing values.5 As a result of Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board's (PMETB's) curricula approval process, medical schools and postgraduate training programmes are incorporating professionalism into their curriculum and the GMC, as the overarching regulatory body (since its merger with PMETB in April 2010), is attempting to assess the professionalism of practising physicians on an ongoing basis.

Since the publication of the RCP working party report Doctors in society,1 the King's Fund and the RCP have held various workshops for junior doctors and medical students examining the challenges that they face and the differences between the way doctors and students think about professionalism. The results of these reports have highlighted the difficulties in formalising the teaching of medical professionalism but also provide encouraging evidence that doctors and students acknowledge the importance and significance of professionalism within their careers.6

Despite this improved understanding of the role of professionalism, graduates find it difficult to define the concept and, when asked, have contrasting views on how it is best taught. There is support for the idea that, although professionalism can be nurtured and developed, the individual must possess the inherent qualities that form the basis of professionalism in the first place. This is an issue medical schools aim to address during the undergraduate selection process. There is also strong debate as to when formal teaching of professionalism should begin and its integration into current medical curriculae.7 These views should be considered and incorporated into teaching methods in order to enhance learning and development.

Method

Over a six-month consecutive period, doctors and medical students in County Durham and Darlington Foundation Trust were asked to complete a paper-based questionnaire during medical lunchtime meetings. Participants were asked to provide information about their gender and grade. The following questions were posed with space for free-text answers:

What is the definition of professionalism?

What does professionalism mean to you?

Where did you learn about professionalism?

Participants were then asked whether they felt professionalism is best taught by lectures, online, tutorials, clinical experience, role play, simulation or apprenticeship by role models. They were also asked how important they thought professionalism is: not at all, somewhat or very.

There were 57 participants with 100% return of the questionnaires (31 females, 23 males and 3 did not specify gender). Of the participants, there were six medical students, 10 foundation year (FY) one, 26 FY two, eight specialist registrars (SpRs), five senor house officers (SHOs) and two participants did not specify their grade.

What is the definition of professionalism?

To classify the responses given to this question and the question ‘What does professionalism mean to you?’, we identified core characteristics within the answers that were common to the current existing definitions of professionalism (Box 1).

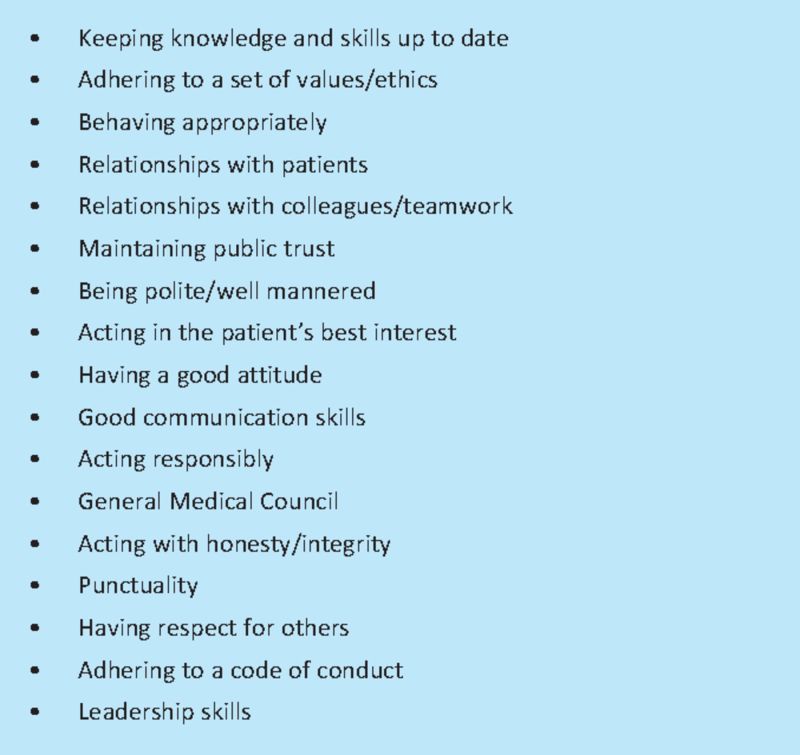

Box 1. What does professionalism mean to you?

Results

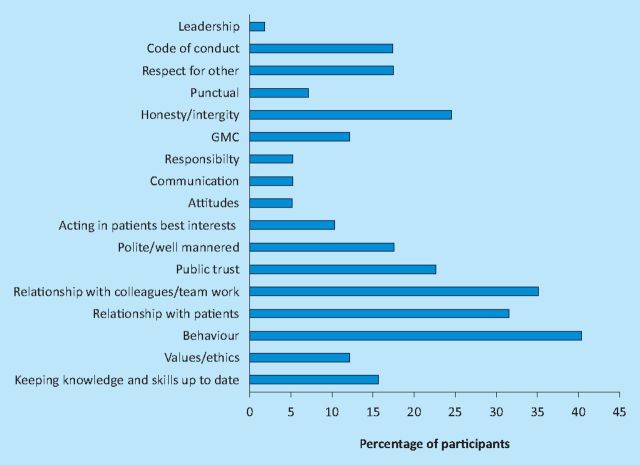

On average, participants identified three core characteristics (range 0–8) in response to the questions. FY2 doctors and medical students tended to identify three or more characteristics in their answer while the remaining doctors recognised an average of less than three characteristics. Fig 1 shows the percentage of participants who included each characteristic in their definition.

Fig 1.

Percentage of participants including each characteristic. GMC = General Medical Council.

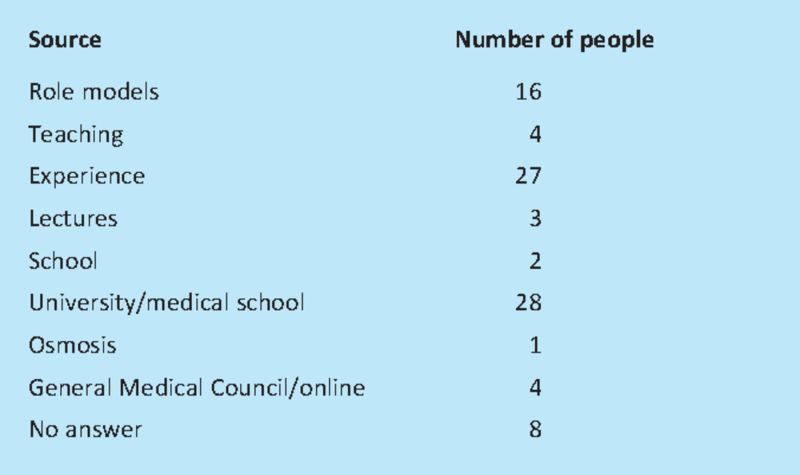

Where did you learn about professionalism?

There were eight sources identified from which participants felt they had learnt professionalism, the most common being medical school or experience. Most participants named only one or two sources from which they had learnt professionalism (Box 2).

Box 2. Number of participants identifying each educational source.

How important is professionalism?

Participants were given the options: very, somewhat or not important. Fifty-five out of 57 felt it was ‘very’ important (96.5%). One person did not specify an answer and one person felt it was ‘somewhat’ important.

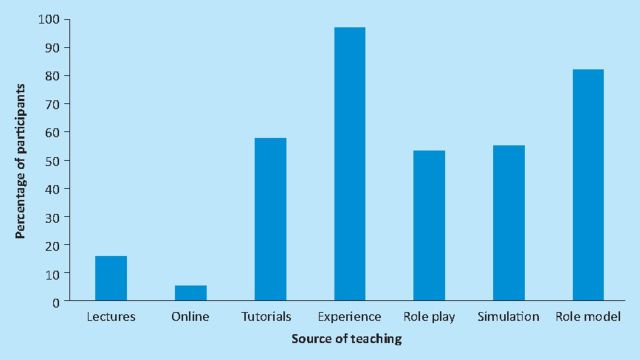

Participants were asked how they felt professionalism was best taught and to specify yes or no from the following options:

lectures

online

tutorials

experience

role play

simulation

role model.

Discussion

Despite concerns that professionalism is considered less important by junior doctors it is clear that the overwhelming majority (96.5%) consider it to be very important. These data suggest that the characteristics associated most with professionalism were behaviour, relationships with colleagues and teamwork and relationships with patients. Very few participants expanded on what was meant by ‘behaviour’ but comments included: ‘acting in a way that is appropriate for a person in a position of trust’ or ‘acting in a manner that is expected by the public’.

A large number of participants identified medical school or university as being the primary source of their education on professionalism with experience and tutorials also being important sources. Role models also have a large role in expanding this learning but several participants commented that this was not always through observation of positive behaviour. However, when asked how they felt professionalism is best taught, role models and learning through experience were identified as being the most useful sources whereas lectures and online teaching were not felt by many to be valuable resources (Fig 2). These findings clearly highlight the current differences between how professionalism is taught and how students feel they learn best.

Fig 2.

How is professionalism best taught?

There is currently a wealth of evidence examining teaching methods for clinical skills and knowledge within the field of medicine. The same cannot be said about professional behaviours and attributes and this deficiency makes it all the more difficult to identify and implement effective methods of not only teaching but also assessing professionalism.6–8 The evidence that does exist highlights critical reflection as integral to professional development. Role models and early clinical contact are identified as an important part of the process of socialisation, allowing students to enter the community of practice that is the medical profession.9 However, negative role modelling encountered during clinical practice can undermine the attitudinal messages of other teaching methods. Peer assessment has also been considered a powerful tool to assess and encourage the formation of professional behaviours10 but this requires specific training on delivering constructive criticism.

A move has been made by some to reduce the apprenticeship aspect of medical learning and also the experiential aspect of medical education with the introduction of specific professionalism curricula. These curricula are closely linked with the definitions of professionalism developed by the RCP and King's Fund and are often delivered in the traditional didactic method or in small, group tutorials. However, as shown, there remains disparity between how the material is taught and how students and graduates feel they learn best about professionalism and more research into this field is needed.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. Report of a Working Party of the Royal College of Physicians of London 2005London: RCP; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Advancing education in medical professionalism: an educational resource from the ACGME Outcome Project. 2004Chicago: ACGME [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein R, Hundert E. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 2002; 287: 226–35 10.1001/jama.287.2.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Medical Council. The duties of a doctor registered with the General Medical Council 2002London: GMC; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruess R, Cruess S. Teaching professionalism: general principles. Med Teach 2006; 28: 205–8 10.1080/01421590600643653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levenson R, Atkinson S, Shepherd S.The 21st century doctor: understanding the doctors of tomorrow 2010London: King's Fund and Royal College of Physicians [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levenson R, Dewar S, Shepherd S.Understanding doctors: harnessing professionalism. 2008London: King's Fund and Royal College of Physicians [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin J, Lloyd M, Singh S. Professional attitudes: can they be taught and assessed in medical education? Clin Med 2002; 2: 217–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldie J, Dowie A, Cotton P, Morrison J. Teaching professionalism in the early years of a medical curriculum: a qualitative study. Med Educ 2007; 41: 610–7 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nofziger AC, Naumburg EH, Davis BJ, Mooney CJ, Epstein RM. Impact of peer assessment on the professional development of medical students: a qualitative study. Academic Medicine 2010; 85: 140–7 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c47a5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]