Introduction

Acute infection represents a substantial proportion of the acute medical workload, with respiratory infection accounting for much of this total.1 This tripartite conference organised by the British Thoracic Society and the British Infection Society in conjunction with the Royal College of Physicians aimed to offer an insight into the recognition and management of some of the important and overlooked aspects of infection at the front door.

Respiratory infection

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) represents about 5% of the acute medical take.2 It is often difficult to decide whether a patient with CAP can be safely managed in an outpatient setting or whether hospital admission is required. The answer lies primarily with clinical judgement, informed by severity assessment using the well validated CURB-65 tool, or CRB-65 within primary care.3 Patients with non-severe CAP (CURB-65 0 or 1) should be considered for outpatient management as mortality in this group is low. However, CURB-65 scores of 3 and above predict a much higher mortality, and as such these patients should be closely observed in a hospital setting. Patients with a CURB-65 score of 2 have an intermediate mortality, and while it is advisable to treat these patients with oral antibiotics they need to be either monitored initially in hospital or followed up promptly as an outpatient to guard against treatment failure.

Pleural infection is common and continues to have a high mortality (20%). Pleural fluid pH helps the physician decide whether an acute effusion is infected or not, and physician-operated bedside pleural ultrasound has substantially improved the scope to sample effusions. Unfortunately fluid pH may be strongly influenced by sampling errors such as delay in analysis and air or lignocaine in the sampling syringe.4 Should patients with empyema initially be managed conservatively or surgically? A conservative approach is advocated if sepsis settles promptly with antibiotics, regardless of radiological improvement. The majority of patients will recover with antibiotics and small bore chest tube drainage, and a conservative approach avoids the risks inherent in surgery. However, early surgical intervention is mandatory if sepsis is not settling with conservative management. Future treatment options include intrapleural DNAse to break up septations and aid drainage (currently undergoing clinical trial), and direct blocking of transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) with monoclonal antibody, which has been shown in mouse models to significantly reduce pleural adhesions and pus formation.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) infection has been an issue for thousands of years, and its incidence continues to increase in the UK. Clinical suspicion relies on assessing whether the patient is high risk for either recent acquisition of TB or reactivation of latent TB. TB infection is often characterised by its insidious clinical presentation, and it is important to have a high index of suspicion when common and usually benign symptoms such as backache, headache, cough or dysuria present chronically and with systemic upset. When assessing such a patient, even at apparent low risk of reactivation or acquisition of TB, it is important for the examining physician to ask themselves whether there is another explanation for this presentation. Never prescribe a third course of antibiotics without considering TB.

Travel is said to broaden the mind but loosen the bowels. In the returning traveller with fever the most important diagnostic tool is a good clinical history. For example, travellers returning from Spain with CAP are at higher risk of resistant pneumococcal or legionella infection. Malaria should always be considered, especially in those travellers returning from Africa, and there are still 1,500 cases in the UK of falciparum malaria per year. The last outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) originated in 2003 in the Far East, and spread globally via infected travellers. SARS demonstrated rapid amplification within hospitals, and there were a number of deaths among healthcare professionals.5 There is as yet no proven treatment.

Acute non-respiratory infection

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign6 has as many fans as detractors, but it has focused the attention of physicians on early recognition and treatment of the septic patient. Mortality from severe sepsis and septic shock increases by 7% for every hour delay there is in the patient receiving antibiotics. Aggressive application of these principles has been shown to reduce mortality, but adherence to the six-hour and 24-hour ‘bundles’ is still poor in many UK hospitals. Steroids in severe sepsis remain controversial, and while it has been demonstrated that many patients in septic shock are functionally hypoadrenal, low-dose hydrocortisone in a recent study showed no effect on mortality.7 Recombinant activated protein C is another controversial (and expensive) treatment, but one large randomised control trial has demonstrated a reduction in mortality in the severely septic patient.8 This finding has not been replicated, and its use remains variable across the UK.

Intravenous (iv) drug use (IVDU) is associated with many difficult consultations in the acute medical unit. Dr Peter Moss gave an inspiring presentation on how this group of ‘difficult’ patients (often ignored in the hope that they will take their own discharge) frequently require the greatest diagnostic effort. An overlooked septic focus in this group is deep vein thrombosis, of whom 50% are bacteraemic. Asymptomatic bacteraemia in IVDUs is common, the most overlooked sources being the heart valves (often tricuspid) and spine. Important issues that are often neglected include addressing the substance misuse, the necessity of gaining appropriate vascular access, testing for blood-borne viruses, and immunisation for hepatitis B.

Bacterial meningitis is a condition where it is essential to make a diagnosis as soon as possible due to the high mortality (21%) and morbidity. The classical triad of fever, neck stiffness, and change in mental status, and Kernig's or Brudzinski's signs are neither sensitive nor specific. Lumbar puncture (LP) is the early investigation of choice, but is often delayed until after a cranial computed tomography (CT) scan has been performed on the grounds that in the presence of raised intracranial pressure, LP can precipitate brain herniation. CT should only precede LP in patients with new-onset seizures, an immunocompromised state, neurological signs suggestive of a space-occupying lesion or a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 10.9 Steroids have been shown to significantly reduce mortality and neurological sequelae,10 and it is now recommended that iv dexamethasone be given with antibiotics in the emergency department. Studies from low income countries have not confirmed this benefit, and the reasons behind this remain unexplained.

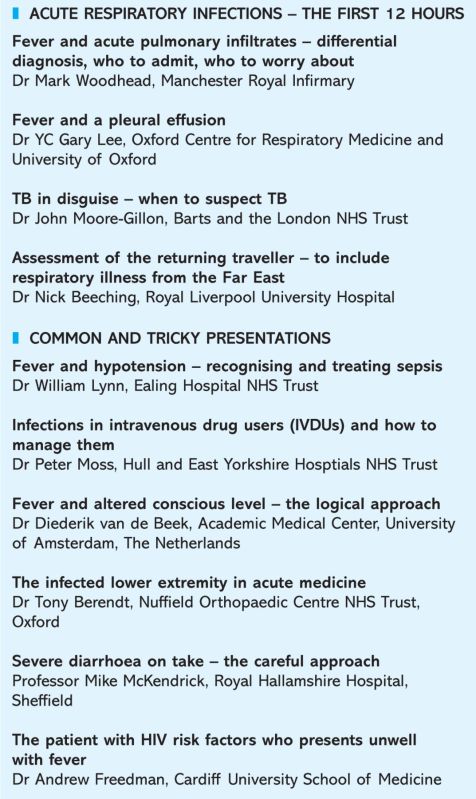

Conference programme.

The infected lower limb is another area where the obvious diagnosis (‘cellulitis’) is often made with very little further thought. Full assessment of the patient and the limb are crucial. The two questions that need to be answered are whether the patient needs an operation and whether they need to be admitted. Necrotising fasciitis is caused by mixed flora infecting the deep fascial layers, stripping blood vessels surrounding bone, joint and muscle, causing necrosis and characteristic violet skin discolouration. Rapid spread through fascial layers causes disproportionate pain and systemic illness. Urgent recognition, surgical debridement, and high dose iv clindamycin and a β lactam are vital, but often this condition is rapidly fatal. Intravenous immunoglobulin is occasionally used, but there remains little evidence to support this practice.

Food poisoning affects one in five people in England and Wales each year, with substantial patient morbidity and financial cost to the NHS (data sourced from www.hpa.org.uk). The clinical history may provide clues as to the infectious agent, but is often unhelpful due to the substantial overlap in syndromes. Colonic absorptive capacity is rapidly swamped, and fluid replacement should be based around the concept of urgent ‘catch up’ followed by adequate ‘maintenance’. Antibiotics generally confer no clinical benefit for most patients, and can have significant disadvantages such as side effects and development of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics may be beneficial with invasive infection, failure of clinical improvement, with high-risk patients, and in certain bacterial and protozoal infections. Toxic dilatation of the colon is an often quoted complication of infective gastroenteritis, but most cases settle with conservative treatment.11

A substantial proportion of HIV infection in the UK is still thought to be undiagnosed (up to 21,600 cases nationally), and first presentation may often be insidious, at an advanced stage, and with a wide variety of symptoms. Risk factors may not be readily volunteered or sought in the acute setting. Within the UK black African population (where the prevalence may be as high as 30%), HIV is commonly associated with TB, which may present atypically. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia is still the most common AIDS-defining illness in Caucasians, and may present with minimal symptoms or signs. HIV presenting acutely may co-exist with multiple other pathologies, which should all be appropriately investigated.

Conclusion

Diagnosis and management of acute infection remain a major challenge within acute medicine, and this conference highlighted the broad spectrum of acute infectious disease. The theme running through the presentations was that while most physicians are adept at recognising and managing common conditions, it is important to be vigilant for those conditions that do not fit into the common pattern. As Tony Berendt remarked, it is easy to spot a pigeon in Trafalgar Square, but it is much more important to spot the eagles.

References

- 1.Hospital Episode Statistics, HESonline.nhs.uk

- 2.Trotter CL, Stuart JM, George R, Miller E. Increasing hospital admissions for pneumonia, England. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:727–33. 10.3201/eid1405.071011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R. et al Defining community-acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003;58:377–82. 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahman NM, Mishra EK, Davies HE, Davies ROJ, Lee YCG. Clinically important factors influencing the diagnostic measurement of pleural fluid pH and glucose. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2008;178:483–90. 10.1164/rccm.200801-062OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung GM, Hedley AJ, Ho LM. et al The epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in the 2003 Hong Kong epidemic: and analysis of all 1755 patients. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM. et al Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 2008;36:296–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D. et al; CORTICUS study group. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. New Engl J Med 2008;358:111–24. 10.1056/NEJMoa071366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF. et al; PROWESS study group. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. New Engl J Med 2001;344:699–709. 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van de Beek D, de Gans J, Tunkel AR, Wijdicks FM. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults. New Engl J Med 2006;354:44–53. 10.1056/NEJMra052116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Gans J, van de Beek D; European dexamethasone in adulthood bacterial meningitis study investigator. Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis. New Engl J Med 2002;247:1549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snowden JA, Young MJ, McKendrick MW. Dilatation of the colon complicating acute self-limiting colitis. QJM 1994;87:55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]