Abstract

HIV is now a treatable medical condition and the majority of those living with the virus remain fit and well on treatment. Despite this a significant number of people in the UK are unaware of their HIV infection and remain at risk to their own health and of passing their virus unwittingly on to others. Late diagnosis is the most important factor associated with HIV-related morbidity and mortality in the UK. Testing for HIV infection is often not performed due to misconceptions held by healthcare workers even when it is clinically indicated and this contributes to missed or late diagnosis. This article summarises the recommendations from the UK national guidelines for HIV testing 2008. The guidelines provide the information needed to enable any clinician to perform an HIV test within good clinical practice and encourage ‘normalisation’ of HIV testing. The full version is available at www.bhiva.org/cms1222621.asp

Key Words: clinical indicator diseases, HIV guidelines, HIV testing, pre-test discussion

Introduction

The UK national guidelines for HIV testing 2008 are intended to facilitate an increase in HIV testing in all healthcare settings as recommended by the UK's Chief Medical Officers and Chief Nursing Officers in order to reduce the proportion of individuals with undiagnosed HIV infection, with the aim of benefiting both individual and public health.1–5 The guidelines provide the information needed to enable any clinician to perform an HIV test within good clinical practice and encourage ‘normalisation’ of HIV testing.

The guidance refers to both diagnostic testing of individuals presenting with ‘clinical indicator diseases’ (ie where HIV infection enters the differential diagnosis) and opportunistic screening of populations where this is indicated on the basis of prevalence data. It must be emphasised that in the UK, HIV testing remains voluntary and confidential. This is entirely possible within any healthcare setting if these guidelines are followed.

Rationale

While the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has transformed the outcome for individuals with HIV infection, there continues to be significant and avoidable morbidity and mortality relating to the virus in the UK.

National audit data have shown that, of deaths occurring among HIV-positive adults in the UK in 2006, 24% were directly attributable to the diagnosis of HIV being made too late for effective treatment.6 Many of these ‘late presenters’ had been seen in the recent past by healthcare professionals without the diagnosis having been made.7

National surveillance data show that approximately one third of all HIV infections in adults in the UK remain undiagnosed and that approximately 25% of newly diagnosed individuals have a CD4 count of less than 200 (an accepted marker of ‘late’ diagnosis).8

Late diagnosis of HIV infection has been associated with increased mortality and morbidity,8 impaired response to HAART,9 and increased cost to healthcare services.10

Furthermore, from a public health perspective, knowledge of HIV status is associated with a reduction in risk behaviour11 and therefore it is anticipated that earlier diagnosis will result in reduced onward transmission.12

Modelling has suggested that over 50% of new infections in the USA occur through transmission from individuals in whom HIV has not been diagnosed, and that routine screening for HIV infection is cost effective and comparable to costs of other routinely offered screening where the prevalence of HIV exceeds 2 in 1,000.13

Research suggests that uptake of testing is increased where universal routine (‘optout’) strategies have been adopted14 – ie where all individuals attending specified settings are offered and recommended an HIV test as part of routine care but an individual has the option to refuse a test.

For this new approach to testing to be beneficial and ethically acceptable, it is imperative that following a positive HIV diagnosis, a newly diagnosed individual is immediately linked into appropriate HIV treatment and care.

Suspected primary HIV infection

Primary HIV infection (PHI), or seroconversion, illness occurs in approximately 80% of individuals, typically two to four weeks after infection. This represents a unique opportunity to prevent onward transmission as an individual is considerably more infectious at this stage. Furthermore this may be the only clinical opportunity to detect HIV before advanced immunosuppression many years later. The features of PHI are non-specific, so that although individuals usually do present to medical services (primary or emergency care), the diagnosis is frequently missed or not suspected.

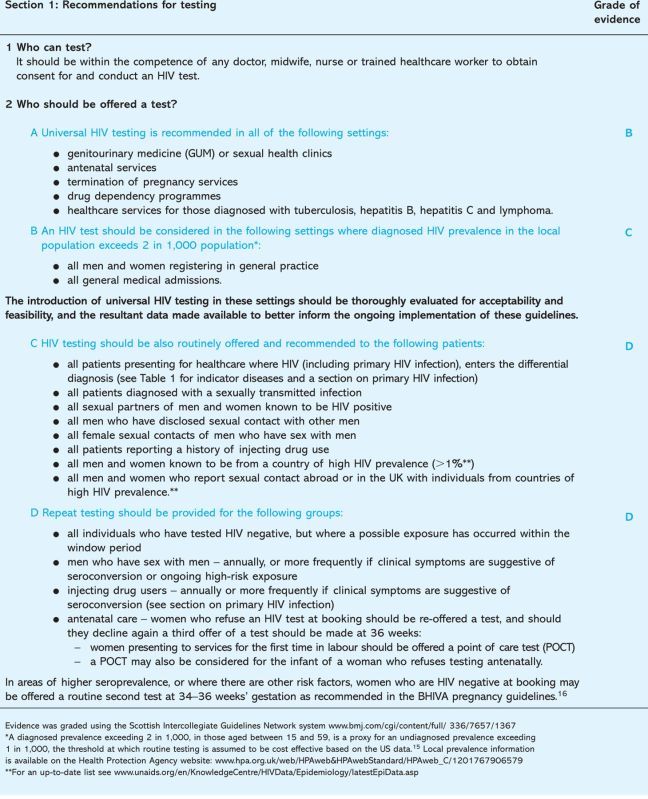

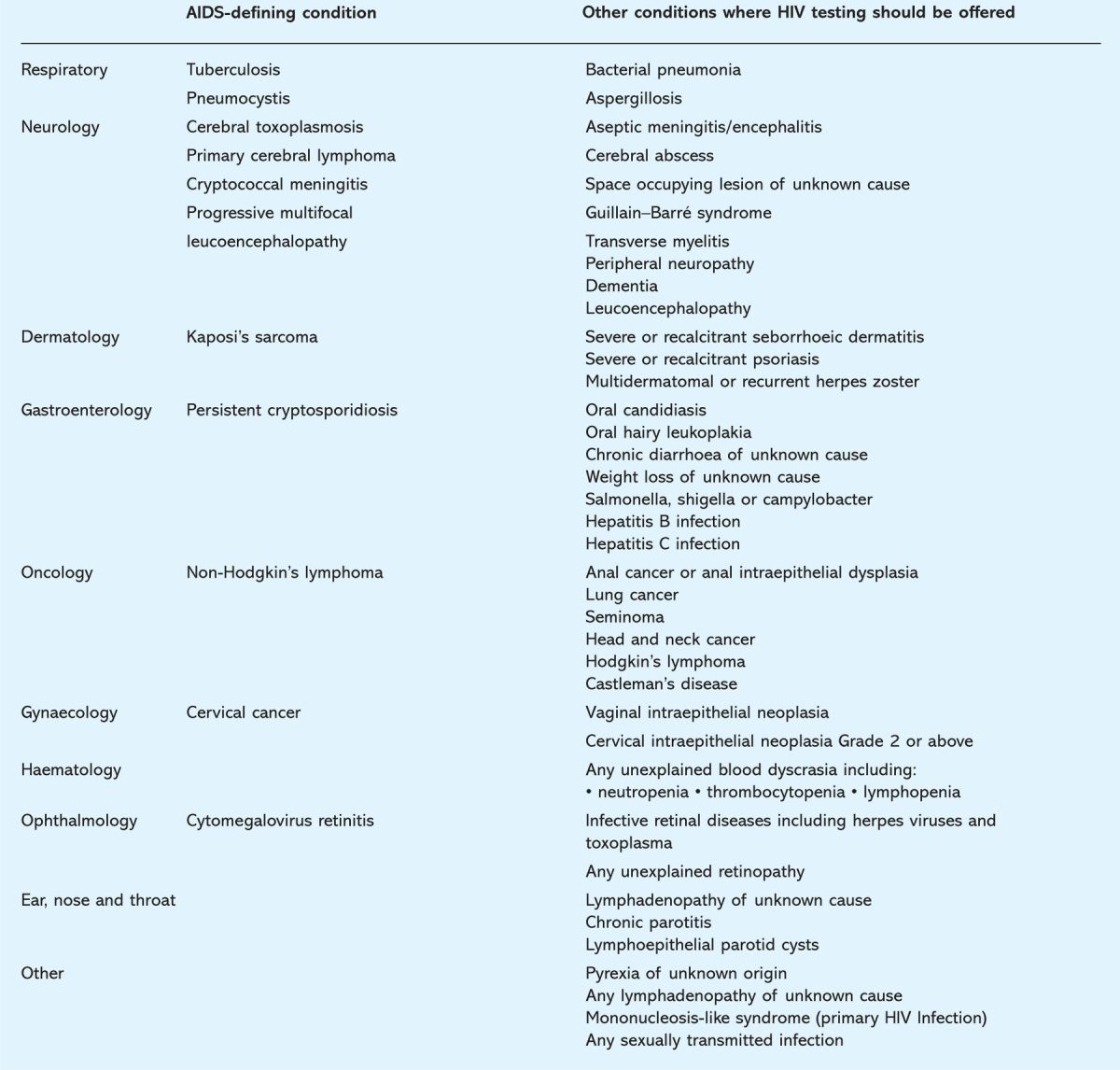

Table 1.

Clinical indicator diseases for adult HIV infection. A similar list for paediatric conditions is included in the full guidelines.1

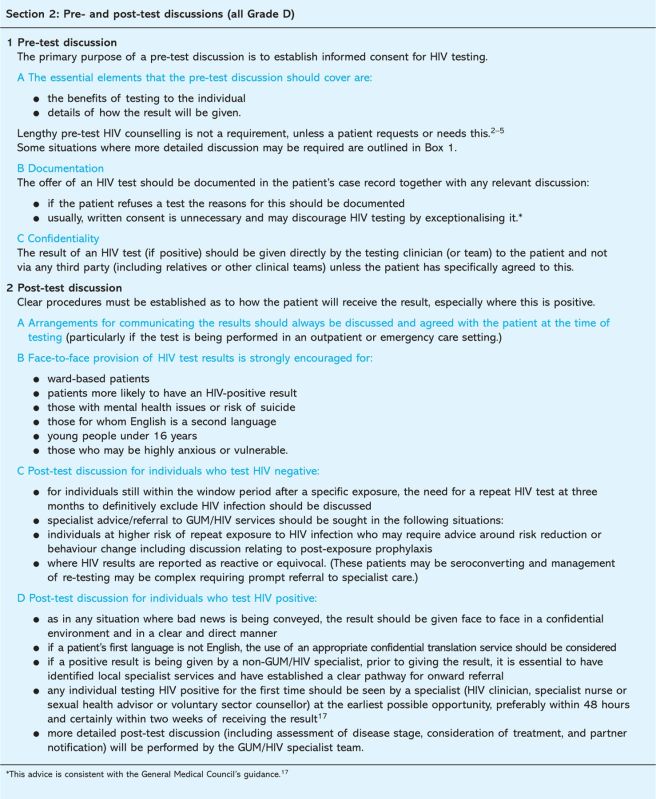

The guidelines.

The guidelines.

The typical symptoms of primary HIV infection include a combination of any of the following:

fever

rash (maculopapular)

myalgia

pharyngitis

headache/aseptic meningitis.

These resolve spontaneously within two to three weeks and therefore if PHI is suspected, this needs to be investigated at the time of presentation and not deferred. Consideration should be given to HIV testing in any person with these symptoms perceived to be at risk of infection. Although with fourth generation tests infection can be detected much earlier than previously, in very recent infection – when patients may be most symptomatic – the test may be negative. In this scenario, if PHI is suspected, either urgent referral to specialist services (genitourinary clinic or HIV service) or a repeat test in seven days is recommended. HIV viral load testing can be used in this clinical setting, but it is recommended that this is only performed with specialist input.

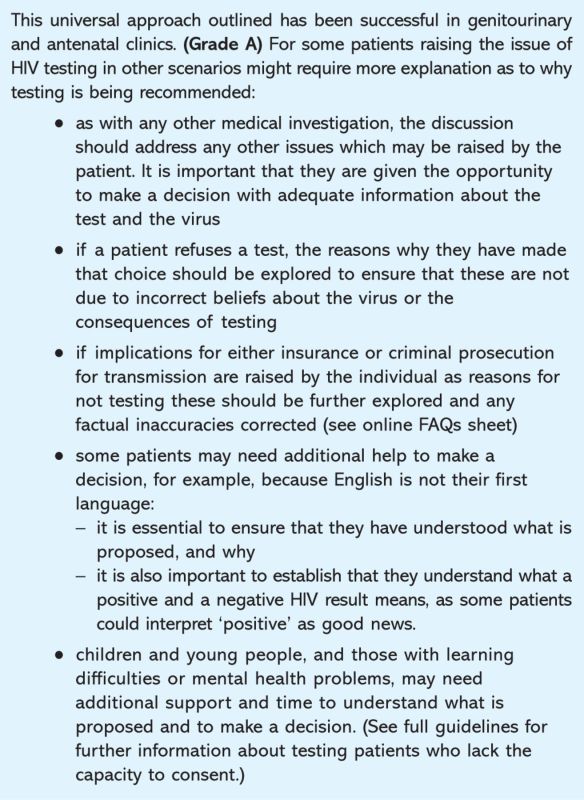

Box 1. Pre-test discussion: situations where more detailed discussion may be required.

Guideline development methodology

A summary of the methodology for development of these guidelines may be found on the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) website (http://rcp-sa-shar03:29137/clinical-standards/organisation/Guidelines/concise-guidelines/Pages/HIV-testing.aspx).

Implications for implementation

The principle requirements for implementation of these guidelines relate to staff training. A list of frequently asked questions is also available on the RCP website (http://rcp-sa-shar03:29137/clinical-standards/organisation/Guidelines/concise-guidelines/Pages/HIV-testing.aspx).

HIV Testing Guidelines Writing Committee

Adrian Palfreeman (British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH)); Martin Fisher (British HIV Association); Ed Ong (British Infection Society); James Wardrope (College of Emergency Medicine); Ewen Stewart (Royal College of General Practitioners); Enrique Castro-Sanchez (Royal College of Nursing); Tim Peto (Royal College of Physicians); Karen Rogstad (Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Heath); Julian Sheather (British Medical Association); Brian Gazzard (Deptartment of Health Expert Advisory Group on AIDS); Deenan Pillay (Deptartment of Health Expert Advisory Group on AIDS); Jane O'Brien (General Medical Council); Valerie Delpech (Health Protection Agency); Ruth Lowbury (Medical Foundation for AIDS and Sexual Health); Russell Fleet (Medical Foundation for AIDS and Sexual Health); Yusuf Azad (National AIDS Trust); Hermione Lyall (Childrens HIV Association); James Hardie (Society of Health Advisors); Godwin Adegbite (UK CAB); Guy Rooney (BASHH Clinical Effectiveness Group); Richard Whitehead (lay representative).

References

- 1.British HIV Association, British Association of Sexual Health and HIV, British Infection Society. UK national guidelines for HIV testing 2008. London: BHIVA, 2008. www.bhiva.org/cms1222621.asp [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donaldson L, Beasley C. Improving the detection and diagnosis of HIV in non-HIV specialties including primary care. London: Department of Health, 2007. www.cas.dh.gov.uk/ViewandAcknowledgment/ViewAlert.aspx?AlertID=100818 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns H, Martin P. Improving the detection and diagnosis of HIV in non-HIV specialties including primary care. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewell T, Kennedy R. Improving the detection and diagnosis of HIV in non-HIV specialties including primary care. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McBride M, Bradley M. Improving the detection and diagnosis of HIV in non-HIV specialties including primary care. Belfast: Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety of Northern Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucas SB, Curtis H, Johnson MA. National review of deaths among HIV-infected adults. Clin Med 2008;8:250–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan AK, Curtis H, Sabin CA. et al Newly diagnosed HIV infections: review in UK and Ireland. BMJ 2005;330:1301–2. 10.1136/bmj.38398.590602.E0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Protection Agency. HIV in the United Kingdom: 2008 report. London: HPA, 2008. www.hpa.org.uk/webw/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1227515299695?p=1158945066450 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stöhr W, Dunn DT, Porter K. et al on behalf of the UK CHIC Study. CD4 cell count and initiation of antiretroviral therapy: trends in seven UK centres, 1997–2003. HIV Med 2007;8:135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krentz HB, Auld MC, Gill MJ. The high cost of medical care for patients who present late (CD4<200 cells/μL) with HIV infection. HIV Med 2004;5:93–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS 2006;20:1447–50. 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vernazza P, Hirschel B, Bernasconi E. et al An HIV-infected person on antiretroviral therapy with completely suppressed viraemia (‘effective ART’) is not sexually infectious [French]. Bull Méd Suisses 2008;89:165–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanders GD, Bayoumi AM, Sundaram V. et al Cost-effectiveness of screening for HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. New Engl J Med 2005;352:570–85. 10.1056/NEJMsa042657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson WM, Johnstone FD, Boyd FM. et al Uptake and acceptability of antenatal HIV testing: randomisedcontrolled trial of different methods of offering the test. BMJ 1998;316:262–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.British HIV Association and Children's HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV infection in pregnant women 2008. HIV Med 2008;9:452–502. www.bashh.org/committees/cgc/reports/final_hiv_point_of_care_tests_guidance_rev080606.pdf 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00619.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.General Medical Council. Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together. London: GMC, 2008. www.gmc-uk.org/news/index.asp#ConsentGuidance [Google Scholar]