Abstract

Migrants comprise a growing proportion of European populations. Although many are healthy, those who do need healthcare often face barriers and the care they receive may be inappropriate to their needs. This paper summarises good practices identified in a review of health services for migrants in Europe. Governments should ensure that migrants are entitled to health services, that the services are appropriate to their needs and that data systems are in place to monitor utilisation and detect inequities. Health services should adopt a ‘whole organisation approach’, in which cultural competence is viewed as much as a task for organisations as for individuals. Health workers should take steps to overcome language, social and cultural barriers to care. In each case, existing examples of good practice are provided. At a time when support is growing in some countries for political parties pursuing anti-immigrant agendas and governments in all countries are pursuing austerity policies, there is a greater need than ever for the public health community to ensure that migrants have access to services that are effective and responsive to their needs.

Key Words: migrant health, Europe

Introduction

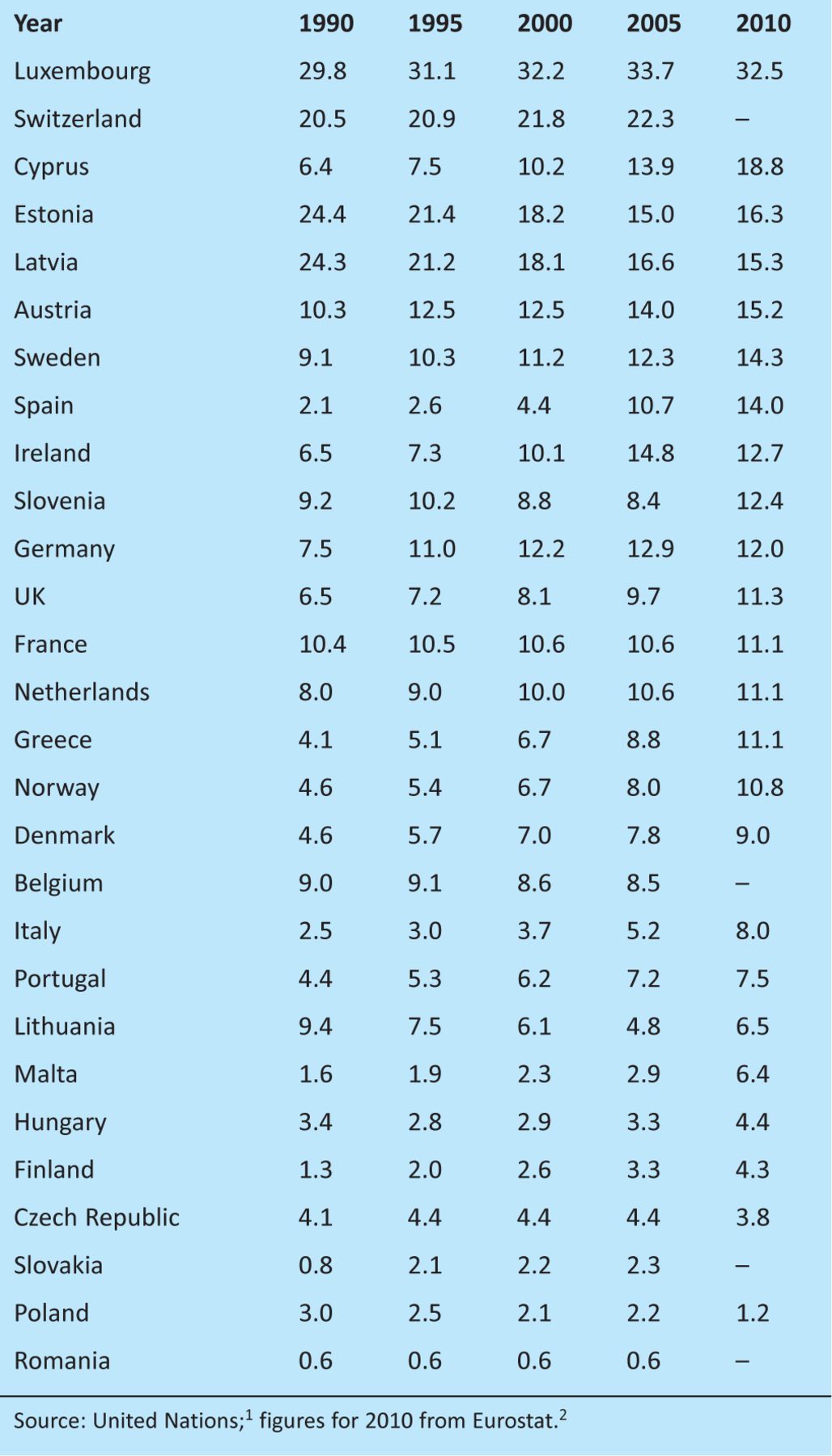

Migrants comprise a substantial, and growing, proportion of European populations (Table 1). In 2009, 4.0% of the European Union (EU)'s total population was comprised of citizens of countries outside the EU.3 Although the present economic crisis might temporarily reduce the inflow of migrants, falling birth rates and ageing populations mean that Europe will continue to need foreign workers.4

Table 1.

International migrants as a percentage of the population in the European Economic Area and Switzerland, 1990–2010, ordered by decreasing percentage in 2010.

Many migrants are young, healthy and have little contact with the health systems of the countries they move to, but some need to access health services and face barriers when trying to do so.5 This is particularly true for undocumented migrants, who, in a number of European countries including the UK, face substantial legal barriers.6 Although the right to health is enshrined in many international and European legal instruments,7 this right has little practical meaning for many migrants. Most European countries grant full equality of access to treatment to third-country nationals who have achieved long-term or permanent residence status, but asylum seekers and undocumented migrants often face restrictions in access to care.8 In 2009, 10 EU countries denied free emergency care to undocumented migrants.6 There are also obstacles beyond the legal entitlement to care.9 For example, migrants, who are more likely to be poor,10 may be particularly deterred from seeking care when user fees are required.11 They may also lack knowledge of the national language, be unfamiliar with the health system, face administrative obstacles and be subject to direct and indirect discrimination.8,12

Legal, cultural and other barriers impede migrants’ internationally recognised right to health and freedom from discrimination.5 Such barriers also lead to inefficiencies due to delayed and therefore more costly care and prevent migrants – and society as a whole – from realising the potential social and economic benefits arising from better health.13 Although international bodies have highlighted the need for increased measures to improve migrants’ access to health services,14,15 few countries have heeded their call, and some, such as the UK, are exploring possibilities to restrict migrants’ access even further.

This analysis draws extensively on a book, newly published by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, that looks at migration and health in the European Union.16 Established experts in a range of issues related to migration and health from across Europe reviewed existing literature and current practices. This was informed by a survey of migrant health policies in Europe and a series of country-specific analyses, which are reported elsewhere.17 We supplemented these with a series of focused literature searches that sought to fill remaining gaps in our quest for evidence of practices that could improve the delivery of health services for migrants, although this largely confirmed the limited amount of robust evidence on the clinical and cost effectiveness of practices in migrant health services, which indicates an urgent need for more studies in this field. We here summarise our findings in relation to good practices in delivering health services for migrants implemented at three levels: government policy, health services and health workers.

Good practices in health care for migrants

Good practices for governments

Entitlements. The most important step that national governments can take to improve migrants’ access to health services is to vest them with the same legal entitlements as other residents of the country. This is a particular issue for undocumented migrants (that is, visa or permit ‘overstayers’, rejected asylum seekers and individuals who have entered a country illegally). Undocumented migrants have been granted virtually complete healthcare coverage in five countries in the EU (France, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain).6 The UK is lagging far behind, granting undocumented migrants an entitlement only to emergency care and giving GPs discretion as to whether to register them as patients. Coverage in England may become even more restricted, as the Department of Health has recently cited concerns about ‘health tourism’ as justification for a review of access to the NHS by undocumented migrants and other ‘non-ordinarily resident’ individuals.18 This runs against current evidence from studies of undocumented migrants, which show that a quest for healthcare benefits is not a motivation for migrating.9,19,20 The belief that generous provision of healthcare coverage is attracting significant numbers of migrants to Europe is simply wrong. Furthermore, confining access to emergency care is expensive and wastes scarce resources, as the administrative costs of identifying and charging undocumented migrants are likely to outweigh any possible savings because the numbers concerned are so small. Finally, under international conventions to which the UK and other EU countries have signed up, all residents of a country have a basic human right to health services.7

Migrant health policies. A second set of policies has been enacted by most European countries with high levels of immigration in order to operationalise the entitlements of migrants under international conventions and national laws, and to ensure the responsiveness of health services to migrants’ needs.21,22 However, these policies are often of limited scope.23 It is also worth noting – particularly in the contemporary context in the UK – that progressive migrant health policies can be reversed when governments change, as was the case in the Netherlands in 2002, when the new government argued that the onus for adaptation should lie on the shoulders of migrants rather than the host society.23

In the UK, widespread attention has been paid for many years to the health of ‘black and minority ethnic [BME] groups’, but policies that specifically target migrants were developed only recently.23 Much could be learnt from the more integrated focus on migrants and ethnic minorities in Ireland and the Netherlands, where there is an emphasis on ‘intercultural’ healthcare.23 Part of the problem is that terminology used in this field in the UK is confusing; in general, the term ‘migrant’ tends to be associated with recent arrivals, while migrants who have been in the UK for more than a few years, as well as descendants of migrants, are usually described as belonging to ‘ethnic minorities’. However, there is no definition of how much time must pass before migrants are considered to belong to a socially, culturally or ethnically distinct group (such as ‘black British’) and the categorisation ignores migrants who feel they do not belong to any such grouping.21

Data collection. In order to develop appropriate policies on migrant health and implement them effectively, a strong evidence base covering the health of migrants, their use of services and the causes of their health problems is required. However, data collection practices vary considerably across Europe and are not as extensive as in some of the ‘traditional’ countries of immigration (such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand). In Europe, the Scandinavian countries have a strong track record in using data effectively, as health records can be coupled to databases storing information about country of origin and thus migrant status, bypassing the need for health agencies to record this information themselves. In the UK, data on ethnicity are collected through registries and surveys but cannot alone be used to ascertain migration status.24

Good practices for health services

Turning to good practices for health services, a first set of recommendations in Europe was provided in 2004 by the Amsterdam declaration ‘Towards migrant friendly hospitals in an ethno-culturally diverse Europe’, while the Office of Minority Health in the USA established ‘Culturally and linguistically appropriate standards’ (CLAS) in 2000. A key concept in this field is the ‘whole organisation approach’, in which cultural competence is viewed as much as a task for organisations as for individuals. Following an extensive research and scoping exercise, Ireland's Health Service Executive has been applying this approach to service provision throughout the country since 2008. The Irish strategy, which includes three key strands (organisational ethos, workplace environment and support for training), could provide lessons for other countries seeking to improve migrant health services, including the UK. Box 1 describes some ways in which organisations can improve their relationship with migrant groups, beyond the basic minimum of providing patient information and consent forms in different languages.

Box 1. Bridging the gap between health services and migrant communities.

Good practices for health workers

Many tools are available to health workers to overcome barriers to delivering high-quality services to migrants.

Overcoming language barriers. A migrant's command of the host language may not be sufficient for adequate communication in a medical encounter. Sometimes a bilingual health worker or other staff member is called upon to provide interpretation. Very often, family members or friends will accompany a patient to provide translation, although this may not be advisable: a systematic review found that the use of professional interpreters is associated with improved clinical care that almost reaches that obtained by patients without language barriers.27 Box 2 describes different forms that interpretation can take.

Box 2. Methods of interpretation.

Overcoming social and cultural barriers. Even when migrants and health workers understand each others’ words, many other barriers can stand in the way. At the most basic level, migrants – like many other vulnerable groups – may have difficulty arranging transportation to the health facility or obtaining time off work to attend appointments; there may also be other legal and informational barriers to overcome. Box 3 describes ways of tackling such access problems.

Box 3. Reaching the ‘hard to reach’.

Apart from practical obstacles to access, other more subtle barriers can undermine the effective delivery of health services. It has become customary to refer to these as ‘cultural barriers’, although some have more to do with the migrant's social situation. Some promising ways to tackle such problems are described in Box 4.

Box 4. Bridging cultural barriers.

The way forward: the need for better evidence to support policy

Since the economic crisis started in 2008, many European countries have been experiencing squeezed health budgets that are impeding access to services, especially for vulnerable groups in the population such as migrants, although increasing numbers of ordinary Greeks are now using street clinics originally created for migrants who lack access to the formal system.30 At the same time, anti-immigration sentiment has increased across Europe in recent years, with a resurgence of parties of the political far right, a rejection of multiculturalism by mainstream parties and a failure by some countries to take responsibility for migrants who fled the Arab Spring and its consequences. In this economic and political climate, it is paramount to remind health policy makers and practitioners of their responsibility to protect and promote the health of their populations, including migrants. The examples of good practice described in this article aim to provide a sense of what is needed.

Acknowledgements

This paper was informed by a project on migration and health in Europe by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies in collaboration with the International Organization for Migration, COST Action IS0603 – Health and Social Care for Migrants and Ethnic Minorities in Europe (HOME), and the Migrant and Ethnic Minority Health Section of the European Public Health Association (EUPHA).

References

- 1.United Nations. Trends in international migrant stock. The 2008 revision (United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2008) New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasileva K. 6.5% of the EU population are foreigners and 9.4% are born abroad. Brussels: Eurostat; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasileva K. Foreigners living in the EU are diverse and largely younger than the nationals of the EU member states. Brussels: Eurostat; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle Y, McKee M, Rechel B, Grundy E. Meeting the challenge of population ageing. BMJ 2009;339:892–4 10.1136/bmj.b3926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Devillé W.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Devillé W, et al. Migration and health in the European Union: an introduction. Migration and health in the European Union 2011. Maidenhead: Open University Press [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuadra CB. Right of access to health care for undocumented migrants in EU: a comparative study of national policies. Eur J Public Health 2011published online. DOI: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr049 10.1093/eurpub/ckr049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pace P.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Devillé W. The right to health of migrants in Europe. Migration and health in the European Union 2011. Maidenhead: Open University Press [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healy J, Mckee M. Accessing health care: responding to diversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson R. Migrants in Europe are losing out on care they are entitled to. BMJ 2009;339:b3895. 10.1136/bmj.b3895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lelkes O, Platt L, Ward T.Ward T, Lelkes O, Sutherland H, Tóth IG. Vulnerable groups: the situation of people with migrant backgrounds. European inequalities: social inclusion and income distribution in the European Union 2009. Budapest: Tarki [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen S, Krasnik A, Rosano A. Registry data for cross-country comparisons of migrants’ healthcare utilization in the EU: a survey study of availability and content. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:210. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Regional Office for Europe. How health systems can address health inequities linked to migration and ethnicity. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Regional Office for Europe. The Tallinn charter: health systems for health and wealth. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peiro MJ, Benedict R. Migrant health policy: the Portugese and Spanish EU presidencies. Eurohealth 2010;16:1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Council of Europe. Recommendation CM/Rec(2011)13 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on mobility, migration and access to health care (adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 16 November 2011 at the 1126th meeting of the ministers’ deputies) Strasbourg: Council of Europe; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Devillé W, editors. Migration and health in the European Union. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2011. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mladovsky P, Rechel B, Ingleby D, McKee M. Responding to diversity: an exploratory study of migrant health policies in Europe. Health Policy 2012;105:1–9 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health. Access to the NHS by foreign nationals – government response to the consultation. London: Stationery Office; 2010. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Consultations/Responsestoconsultations/DH_125271 [Accessed 3 November 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero-Ortuño R. Access to health care for illegal immigrants in the EU: should we be concerned. Eur J Health Law 2004;11:245–72 [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Migrants in an irregular situation: access to healthcare in 10 European Union Member States. Vienna: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mladovsky P. A framework for analysing migrant health policies in Europe. Health Policy 2009;93:55–63 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padilla B, Portugal R, Ingleby D.Fernandes A, Pereira Miguel J. Health and migration in the European Union: good practices. Health and migration in the European Union: better health for all in an inclusive society 2009. Lisbon: Instituto Nacional de Saúde Doutor Ricardo Jorge; 101–15et al.In: eds.–www.insa.pt/sites/INSA/Portugues/Publicacoes/Outros/Paginas/HealthMigrationEU2.aspx [Accessed 03 November 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mladovsky P.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Devillé W, et al. Migrant health policies in Europe. Migration and health in the European Union 2011. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Deville W.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Devillé W, et al. Monitoring the health of migrants. Migration and health in the European Union 2011. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schouten BC, Meeuwesen L. Cultural differences in medical communication: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 2006;64:21–34 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netto G, Bhopal R, Lederle N. How can health promotion interventions be adapted for minority ethnic communities? Five principles for guiding the development of behavioural interventions. Health Promot Int 2010;25:248–57et al. 10.1093/heapro/daq012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res 2007;42:727–54 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karl-Trummer U, Novak-Zezula S, Metzler B. Access to health care for undocumented migrants in the EU: a first landscape of NowHereland. Eurohealth 2010;16:13–6 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bozorgmehr K, Saint VA, Tinnemann P. The ‘global health’ education framework: a conceptual guide for monitoring, evaluation and practice. Global Health 2011;7:8. 10.1186/1744-8603-7-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Papanicolas I. Health effects of financial crisis: omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet 2011;378:1457–8et al. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61556-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]