ABSTRACT

It takes upwards of ten years for alcohol-related liver disease to progress from fatty liver through fibrosis to cirrhosis to acute on chronic liver failure. This process is silent and symptom free and can easily be missed in primary care, usually presenting with advanced cirrhosis. At this late stage, management consists of expert supportive care, with prompt identification and treatment of bleeding, sepsis and renal problems, as well as support to change behaviour and stop harmful alcohol consumption. There are opportunities to improve care by bringing liver care everywhere up to the standards of the best liver units, as detailed in the Lancet Commission report. We also need a fundamental rethink of the technologies and approaches used in primary care to detect and intervene in liver disease at a much earlier stage. However, the most effective and cost-effective measure would be a proper evidence-based alcohol strategy.

KEYWORDS: Liver, cirrhosis, alcohol, alcohol policy, Lancet Commission, early detection, minimum unit price

Key points

Early identification of those with asymptomatic and reversible liver disease and/or hazardous drinking habits is vital to allow early intervention

Better in-hospital care must be available for those with established symptomatic and advanced alcoholic cirrhosis, including excellent supportive management, the formation of specialist liver units in district general hospitals and the introduction of alcohol care teams

A major shift in UK government policy is required to reduce per capita alcohol consumption, in order to make a meaningful impact on death rates from liver disease

Background – the scale of the issue in the UK

This review was drafted alongside the Lancet Commission: Addressing the crisis of liver disease in the UK; evidence-based recommendations of an expert panel aimed at tackling rising numbers of premature deaths due to liver injury.1

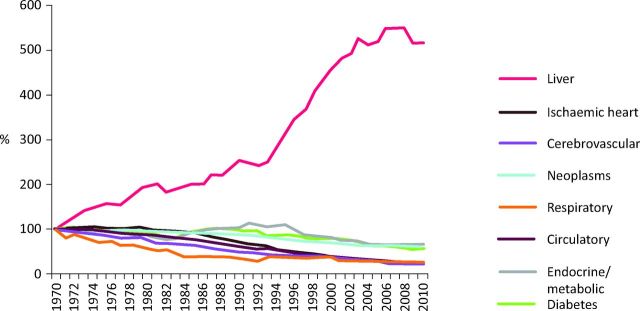

The Commission could not have come at a more important time; liver disease in the UK is attracting a growing list of staggering statistics. It is the only major cause of mortality increasing year on year thanks to a rise in alcohol consumption, obesity and viral hepatitis (Fig 1). Standardised mortality rates have risen by 400% since 1970 and 500% in the under 65s, a glaring exception to nearly every other major cause of death in the UK.1 It is a disease of working-age people and is the third largest cause of premature mortality in the UK, with 62,000 years of working life lost annually.1 Currently, 600,000 individuals in the UK have liver disease of which 10% are cirrhotic. In 2012 this equated to 57,682 hospital admissions and 10,948 deaths, up by 62% and 40% respectively over the past decade.1 The main driver of this increase is alcohol.

Fig 1.

Standardised UK mortality rate data (age 0–64 years) from the WHO-HFA database normalised to 100% in 1970, and subsequent trends. Adapted with permission.1

Alcohol accounts for three-quarters of deaths due to liver disease1 and costs the NHS £3.5 billion per annum.2 Alcohol-related deaths mirror population level alcohol consumption,3 but more specifically have been driven by the consumption of cheap, strong alcoholic drinks.4 Consequently, alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) has become a disease of the poor and is one of the most major health inequalities in this country.5

Liver disease is largely silent. The tragedy is that 80% of liver disease presents as an emergency due to decompensated cirrhosis or alcoholic hepatitis, both associated with complications that carry grave mortality rates. However, alcohol dependency is rarely silent and it is vital clinicians intervene early to change harmful behaviour. The fact that one-quarter of the UK population are hazardous drinkers means this responsibility rests with all of us. There is no specific treatment for alcoholic liver disease other than excellent supportive care. Unfortunately this is received by less than half of patients according to the 2013 NCEPOD report.6 It is imperative that patients are managed by alcohol care teams and receive community follow up to establish long-lasting behavioural change. We hope to address the steps that can be taken in both primary and secondary care, but also at a population level, in order to tackle one of the most challenging non-communicable health issues of the 21st century.

Hospital presentation and management of alcohol-related liver disease

The 2013 NCEPOD report into deaths from ArLD spoke of ‘missed opportunities’ due to the mismanagement of decompensated liver disease. Dr Foster data however shows a steady decline in hospital mortality from liver disease over the last decade (Nick Sheron, unpublished data). This is almost certainly a result of improvements in best supportive care; excellent fluid management, 24-hour endoscopy, widespread use of variceal banding and terlipressin, advancements in resuscitation, including use of blood products, and increased recognition of sepsis, which affects up to 50% of inpatients with cirrhosis7,8 and is the leading cause of death in this group.9 However, overall survival has remained unchanged (Nick Sheron, unpublished data)1 as a result of the fact that alcohol consumption remains the only independent predictor of survival. Each ‘successful’ discharge can only impact mortality rates if followed by a sustained change in behavior. Put simply, the aim of the liver clinician is to try to keep the patient alive long enough to allow them to benefit from alcohol cessation.

Management of alcohol withdrawal

Early detection of patients at risk of alcohol withdrawal is vital. Benzodiazepines are the drug of choice with no significant difference between subtypes.10 Withdrawal regimes can be fixed or symptom triggered. The latter allows for a reduction in withdrawal duration and total dose of benzodiazepine but requires 24-hour observation by trained nursing staff.

Management of alcoholic hepatitis and decompensated cirrhosis

Alcoholic hepatitis is a clinical syndrome defined by recent onset of jaundice and/or ascites in a patient with recent high alcohol consumption. It may occur on a background of cirrhosis. Mortality rates are substantial at 50–65% at 28 days in patients with a Maddrey's score ≥32.11,12 Pentoxylline and corticosteroids were used as specific therapies until recently when the UK STOPPAH trial concluded neither impacted significantly on three-month or one-year mortality.13,14 Similarly, N-acetylcystine also fails to improve six-month survival.15

The backbone of alcoholic hepatitis management is excellent supportive care while waiting for the liver to regenerate in the absence of a toxin. Rises in creatinine of >50% should trigger withdrawal of diuretics and nephrotoxins, accompanied by volume expansion with human albumin. If renal function continues to deteriorate, hepatorenal syndrome should be considered16 and a vasopressin analogue (eg terlipressin) introduced.17 Patients with ArLD are often in a catabolic state. If nutritional requirements cannot be met, orally enteral nutrition should be given.18 Supplementation with B-complex and fat-soluble vitamins is imperative. Encephalopathy should be managed by addressing the underlying cause, prompt use of lactulose or enemas followed by rifaximin second line.18 Nutrition takes priority and patients should continue to receive 1.5 g/kg of protein per day.18 Clinicians should have a low threshold for screening and treating sepsis. In patients with cirrhosis the addition of albumin in combination with antibiotics improves renal and circulatory function, although a survival benefit has only been conclusively demonstrated for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).19 Administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics in the event of a variceal bleed, and norfloxacin or ciprofloxacin prophylaxis following SBP are vital.

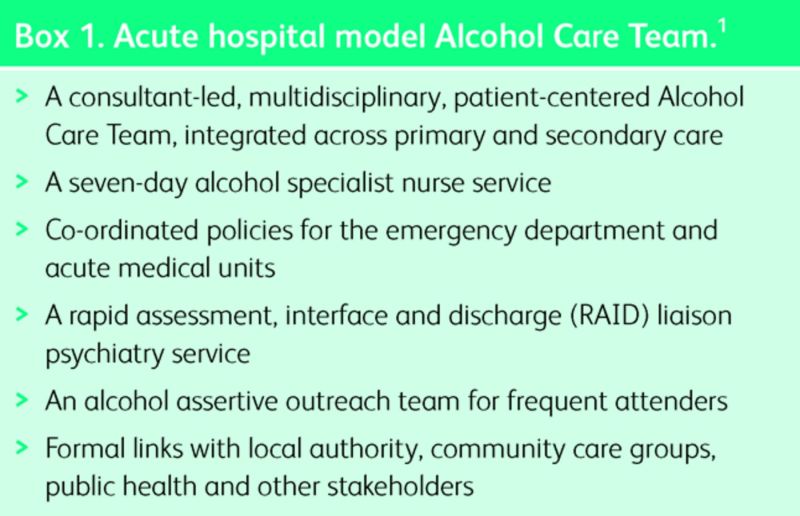

Around half of patients will stop drinking at their first presentation with alcohol-related cirrhosis, and abstinence is the only predictor of long-term survival.20 Unfortunately, for many it is too late; one-third die early because they did not stop drinking in time, one-third die later from continued alcohol intake and one-third survive – we have termed this ‘the law of thirds’. The quality of liver care may be a factor. For example a recent NCEPOD report found that less than one-quarter of hospital trusts have a multidisciplinary Alcohol Care Team,6 despite evidence that they can improve quality of life and reduce hospital readmissions.21,22 Every district general hospital and specialist liver unit will now be required to form such a team which will function as an integrated network across primary and secondary care (Box 1).1

Box 1. Acute hospital model Alcohol Care Team.1

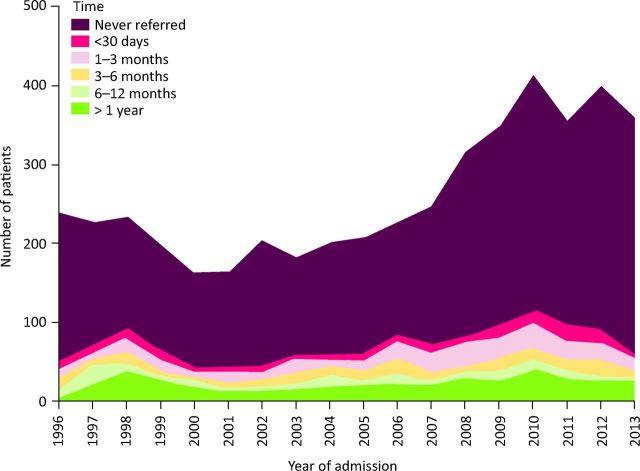

Alcohol in the community and identification of patients at risk of liver disease

We are currently detecting liver disease too late. An analysis of 4,313 patients admitted for the first time to University Hospitals Southampton with cirrhosis or liver failure revealed that 73% had not been referred to a liver clinic (Fig 2), a clear example that early detection is not happening. One- and five-year survival rates for patients with cirrhosis in the community are 0.84 and 0.66 respectively, reduced to 0.55 and 0.31 following hospitalisation.23 Yet the lag time from injury to end-stage disease is substantial, a golden opportunity to intervene. While abstinence later on in disease can produce dramatic effects in terms of histological improvements and decreased portal pressure.20,24–29

Fig 2.

Time period between referral to a liver clinic and the first admission with cirrhosis or liver failure. Adapted with permission.1

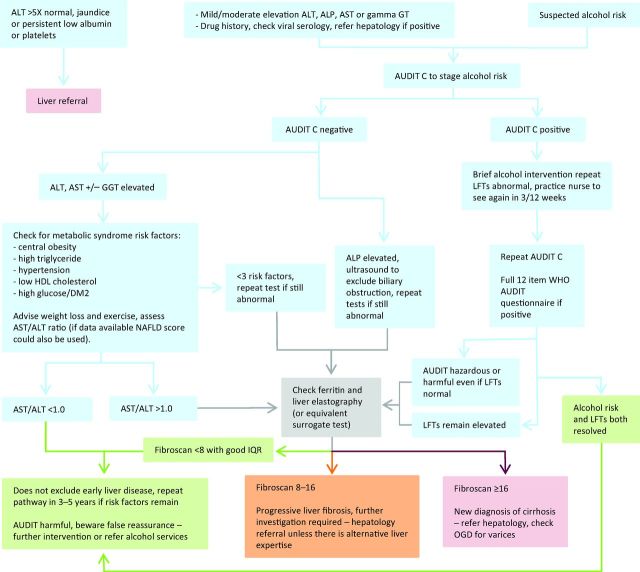

Liver disease is symptomatically silent. Physicians therefore need to find patients with ArLD early through the identification of abnormal liver biochemistry or high-risk groups. The Lancet Commission has published a standardised pathway applicable for alcohol, obesity and viral-related liver disease to guide decision making past these points (Fig 3).1

Fig 3.

Diagnostic pathway. AUDIT-C: a three-question test (taken from the ten-question AUDIT) and screening method to identify hazardous alcohol consumption on a scale of 0–12; a score of 4+ indicates hazardous people or are at increasing risk, 7+ indicates harmful drinkers or of higher risk, and 9+ indicates possible alcohol dependency. Red represents when secondary care referral is indicated for probable serious liver disease, acute hepatic injury, severe fibrosis or cirrhosis. Orange represents when secondary care referral is usually indicated for probable progressive liver fibrosis but not cirrhosis. Green represents no evidence of significant liver fibrosis at this stage, risk factors should be addressed and the pathway repeated after an interval if they remain. Blue represents the usual pathway. Grey represents the final decision box. AUDIT C = alcohol use disorders identification test-consumption; ALP = alkaline phosphatase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; DM2 = type 2 diabetes; GGT = γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; HDL = high density lipoprotein; IQR = interquartile range; LFTs = liver function tests; NAFLD = non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; OGD = oesophogastroduodenoscopy. Adapted with permission.1

Alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis may cause a rise in transaminases, but elevation of these enzymes is non-specific and they may be normal. Changes in bilirubin and albumin indicate late disease and are also poor screening tools. Serum γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) level and liver elastography have the potential to further distinguish patients likely to develop progressive disease who should be referred. Within the community, GGT has the highest predictive value in terms of liver disease and mortality30 and can enhance behavioural change in heavy drinkers.31 Liver elastography is the current ‘gold standard’ for assessment of fibrosis and the commission has suggested it be included in standard operating procedure for liver ultrasound requests from the community.1 It is fast, relatively cheap and has strong positive and negative predictive value. Surrogate markers of fibrosis including hyaluronic acid and procollagen 3 N-terminal peptide (P3NP) can also detect fibrosis, and reduce harmful drinking through their incorporation into the Southampton traffic light grades.32

Risk factor identification is an alternative tool to detect liver disease in the community. Primary care is in a strong position to identify this group, as patients with alcohol dependency make frequent GP visits and liver disease shares lifestyle risk factors already monitored by GPs in annual cardiac, renal and diabetic checks. The Commission advises that liver disease be positioned within the ‘big five major chronic, preventable, lifestyle related diseases’ in primary care with the introduction of Quality Outcome Framework incentives.1 Many patients have more than one risk factor for liver disease and detection of concomitant obesity, diabetes and viral hepatitis cannot be underestimated as this will significantly accelerate time to cirrhosis.

A GP or community nurse should provide a brief intervention as a first-line measure in all patients suspected of drinking heavily. This involves offering feedback on alcohol use and harm, coping strategies, increasing motivation and the development of a plan to reduce intake. It is a huge misconception that such interventions are not effective. A wealth of studies have demonstrated benefits in terms of abstinence, reversal of liver damage and cost effectiveness.33 Treatment of between 8 and 12 people can result in 1 person stopping harmful drinking and 10% reducing their intake to safe levels.34 Outcomes improve further when combined with assessments for fibrosis.35 There is also good evidence that most patients are able to stop drinking when advised appropriately by a liver specialist.20

Minimum unit pricing and solutions to the problem on the national scale

Minimum unit pricing

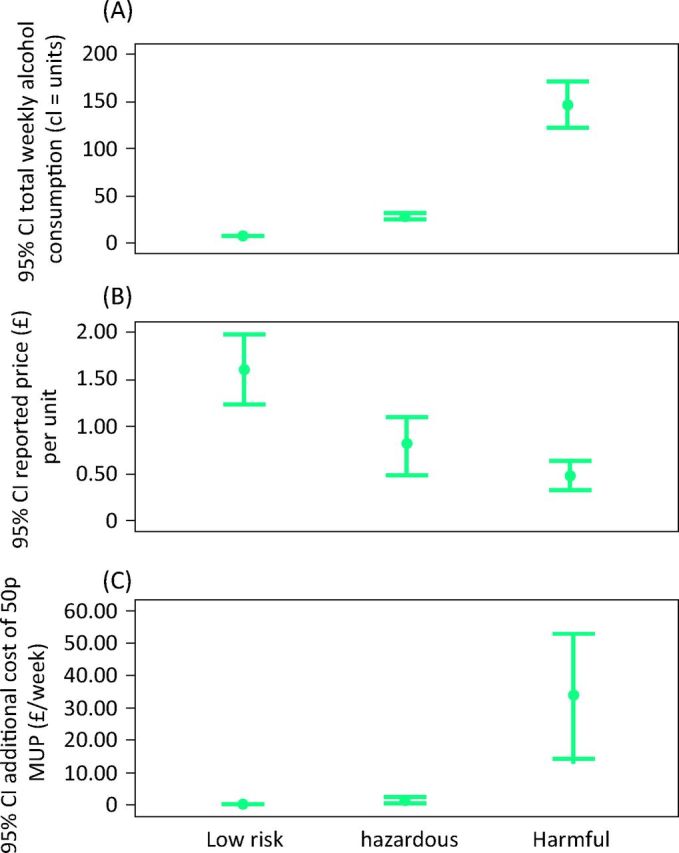

The biggest drivers of alcohol-related deaths in the UK are cheap alcohol, a move to supermarket sales and stronger alcohol content.36,37 Minimum unit pricing (MUP) is an extremely targeted policy. It will almost exclusively affect consumers of cheap strong alcohol, ie those who drink in a harmful or dependent manner4 and those likely to die from liver disease.1,4 In a large UK study, patients with ArLD drank 150 units/week at 33p/unit, one-third of that spent by low-risk drinkers.4 Consequently the impact of MUP will be 200 times greater for harmful drinkers (Fig 4). It is predicted that a 50p MUP would save 3,400 lives per year and reduce hospital admissions by 100,000,38 supported by real world data from Canada.39 The exciting news is that this occurred within 12–24 months.39 Finally, an approximation of the Pareto principle or 80:20 rule can be applied to alcohol; one-quarter of the UK population are hazardous and harmful drinkers, but they account for three-quarters of alcohol sales.40–43 This may go some way to explain opposition from the drinks industry to evidence-based alcohol policy.

Fig 4.

(A) Mean weekly alcohol consumption, (B) price paid per unit of alcohol and (C) impact of a 50p MUP of alcohol in 404 patients with liver disease, categorised according to their level of alcohol drinking. Adapted with permission.1 CI = confidence interval; MUP = minimum unit pricing.

Alcohol duty and VAT

There is strong evidence that the burden of harm in the population is linked to the average per capita consumption.1 Fifty years of increasing affordability of alcohol in the UK has led to increased population consumption, and deaths rates from cirrhosis have followed.3 Price is one of the most robust methods of altering behavior, but a shift towards supermarket sales and failure of taxation to match increases in household income has led to a significant drop in the real price of alcohol. While duty on alcohol increased in 2008, resulting in a decrease in per capita consumption and levelling off of soaring rates of liver deaths, this was no match for the preceding rise, and remarkably, has since been withdrawn.44

Marketing

Alcohol marketing is important particularly in its influence on young people.45 Research commissioned by the European Commission found that marketing changes behavior, leading to children drinking at an earlier age and drinking more.46 This has translated into increased harm with over 15,000 under 18 year olds being admitted to hospital with alcohol-specific conditions in the UK between 2000 and 2013.47 Furthermore, harmful drinking habits acquired in childhood predict alcohol abuse in adulthood.35 While advertising through TV, sports and music events impacts teenagers to a level not experienced by the previous generation, advertisement of alcohol-related harm, including heath-warning labels, remains limited.

Availability

As alcohol has become more affordable, it has also become more visible. It is increasingly sold and drunk at a wide range of environments, including cinemas, hairdressers and service stations with 24/7 availability. Relaxed closing times and licensing laws, which fail to prioritise the health of the public, came into effect in 2004, accompanying a cultural change towards continental café style drinking throughout the day.

Conclusion

The increasing trend in mortality from alcohol-related liver disease has been driven by governments making strong alcohol much cheaper, and the drinks industry making alcohol more available. The fact that liver disease develops with no signs or symptoms means that it is often missed in primary care, and expert services in secondary care have not grown to meet demand.

With regard to solutions: there is a strong evidence base for effective alcohol policy that can reverse trends in liver mortality. New technology means that it is easier to identify and stage liver disease in primary care, and interventions to reduce harmful drinking are effective and cost effective.

Once cirrhosis has developed, the critical job for the secondary care liver physician is to keep patients alive with the best possible supportive care, but the only determinant of long-term survival is abstinence after discharge; with alcohol care teams in joined up services to help maintain this vital behaviour change.

References

- 1 .Williams R, Aspinall R, Bellis M, et al. Addressing the crisis of liver disease in the UK: A blueprint for attaining excellence in healthcare for liver disease and reducing premature mortality from the major lifestyle issues of excess alcohol consumption, obesity and viral. Lancet 2014;384:1953–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2 .Department of Health Alcohol strategy published. London: DoH, 2012. Available online at www.gov.uk/government/news/alcohol-strategy-published [Accessed 17 February 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 3 .Academy of Medical Sciences Calling time – The nation's drinking as a major health issue. London: Academy of Medical Sciences, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4 .Sheron N, Chilcott F, Matthews L, Challoner B, Thomas M. Impact of minimum price per unit of alcohol on patients with liver disease in the UK. Clin Med 2014;14:396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5 .Siegler V, Al-Hamad A, Johnson B, Wells C, Sheron N. Social inequalities in alcohol-related adult mortality by National Statistics Socio-economic Classification, England and Wales, 2001-03. Health Stat Q 2011;Summer:4–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6 .Juniper M, Smith N, Kelly K, Mason M. Measuring the units – a review of patients who died with alcohol-related liver disease. London: National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7 .Navasa M, Rodés J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis. Liver Int 2004;24:277–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8 .Borzio M, Salerno F, Piantoni L, et al. Bacterial infection in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a multicentre prospective study. Dig Liver Dis 33:41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9 .Wong F, Bernardi M, Balk R, et al. Sepsis in cirrhosis: report on the 7th meeting of the International Ascites Club. Gut 2005;54:718–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 .Amato L, Minozzi S, Vecchi S, Davoli M. Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(3): CD005063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11 .Carithers RL, Herlong HF, Diehl AM, et al. Methylprednisolone therapy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. A randomized multicenter trial. Ann Intern Med 1989;110:685–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12 .Phillips M, Curtis H, Portmann B, Donaldson N, Bomford A, O’Grady J. Antioxidants versus corticosteroids in the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis – a randomised clinical trial. J Hepatol 2006;44:784–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13 .Forrest E, Mellor J, Stanton L, et al. Steroids or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis (STOPAH): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2013;14:262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14 .Thursz PM. STOPAH Trial Update. Gateshead: BASL Annual Meeting, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15 .Nguyen-Khac E, Thevenot T, Piquet M-A, et al. Glucocorticoids plus N-acetylcysteine in severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1781–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16 .European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2010;53:397–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17 .Sanyal AJ, Boyer T, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. A randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of terlipressin for type 1 hepatorenal syndrome. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1360–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18 .European Association for the Study of Liver EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol 2012;57:399–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19 .Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med 1999;341:403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20 .Verrill C, Markham H, Templeton A, Carr NJ, Sheron N. Alcohol-related cirrhosis – early abstinence is a key factor in prognosis, even in the most severe cases. Addiction 2009;104:768–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21 .Alcohol Health Alliance UK Health First: an evidence based alcohol strategy for the UK. Stirling: University of Stirling, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22 .Quality and Productivity Alcohol care teams: reducing acute hospital admissions and improving quality of care. The British Society of Gastroenterology and the Royal Bolton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23 .Ratib S, Fleming KM, Crooks CJ, Aithal GP, West J. 1 and 5 year survival estimates for people with cirrhosis of the liver in England, 1998–2009: a large population study. J Hepatol 2014;60:282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24 .Raynard B, Balian A, Fallik D, et al. Risk factors of fibrosis in alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology 2002;35:635–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25 .Pessione F, Ramond MJ, Peters L, et al. Five-year survival predictive factors in patients with excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis. Effect of alcoholic hepatitis, smoking and abstinence. Liver Int 2003;23:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26 .Alvarez MA, Cirera I, Solà R, Bargalló A, Morillas RM, Planas R. Long-term clinical course of decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis: a prospective study of 165 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol 45:906–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27 .Teli MR, Day CP, Burt AD, Bennett MK, James OF. Determinants of progression to cirrhosis or fibrosis in pure alcoholic fatty liver. Lancet 1995;346:987–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28 .Muntaner L, Altamirano JT, Augustin S, et al. High doses of beta-blockers and alcohol abstinence improve long-term rebleeding and mortality in cirrhotic patients after an acute variceal bleeding. Liver Int 2010;30:1123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29 .Runyon BA. Historical aspects of treatment of patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Semin Liver Dis 1997;17:163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30 .McLernon DJ, Donnan PT, Sullivan FM, et al. Prediction of liver disease in patients whose liver function tests have been checked in primary care: model development and validation using population-based observational cohorts. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31 .Peterson B, Trell E, Kristenson H. Comparison of gamma-glutamyltransferase and questionnaire test as alcohol indicators in different risk groups. Drug Alcohol Depend 1983;11:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32 .Sheron N, Moore M, Ansett S, Parsons C, Bateman A. Developing a ‘traffic light’ test with potential for rational early diagnosis of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in the community. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e616–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33 .Kaner EFS, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2007;(2):CD004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34 .Kaner EFS, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev 2009;28:301–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35 .Sheron N, Moore M, O’Brien W, Harris S, Roderick P. Feasibility of detection and intervention for alcohol-related liver disease in the community: the Alcohol and Liver Disease Detection study (ALDDeS). Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e698–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36 .Jewell J, Sheron N. Trends in European liver death rates: implications for alcohol policy. Clin Med 2010;10:259–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37 .Sheron N, Hawkey C, Gilmore I. Projections of alcohol deaths – a wake-up call. Lancet 2011;377:1297–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38 .Donaldson L. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer for England. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39 .Zhao J, Stockwell T, Martin G, et al. The relationship between minimum alcohol prices, outlet densities and alcohol-attributable deaths in British Columbia, 2002-09. Addiction 2013;108:1059–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40 .Habel C, Rungie C, Lockshin L, Spawton T. The Pareto Effect (80:20 rule) in consumption of liquor: a preliminary discussion. Available online at http://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/handle/2440/46536 [Accessed 22 October 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 41 .Wikipedia Pareto principle. Available online at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pareto_principle [Accessed 20 January 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 42 .Baumberg B. How will alcohol sales in the UK be affected if drinkers follow government guidelines? Alcohol Alcohol 2009;44:523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43 .Department of Health Safe, Sensible, Social – consultation on further action. London: DoH, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44 .Yeomans J. Budget 2014. Osborne scraps the alcohol duty escalator. The Grocer, 19 May 2014. Available online at www.thegrocer.co.uk/home/topics/budget-2014-osborne-scraps-the-alcohol-duty-escalator/355647.article [Accessed 20 January 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 45 .Hastings G, Sheron N. Alcohol marketing: grooming the next generation: children are more exposed than adults and need much stronger protection. BMJ 2013;346:f1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46 .Science Group of the European Alcohol and Health Forum Does marketing communication impact on the volume and patterns of consumption of alcoholic beverages, especially by young people? a review of longitudinal studies. Brussels: European Alcohol and Health Forum, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47 .Shield KD, Rehm J, Rehm MX, Gmel G, Drummond C. The potential impact of increased treatment rates for alcohol dependence in the United Kingdom in 2004. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]