ABSTRACT

There is a widespread perception that trainees in medicine in the UK are ‘not as good as they used to be’ and reduction in hours of training is often cited as one cause. However, there are no data on the current experience of medical trainees in general medicine. The experience of foundation year doctors (FY1/2) and core medical trainees (CTs) in the management of 10 common medical conditions, eight common medical procedures and other aspects of medical training were collected by national survey in 2011. Trainees reported finding out-of-hours care the best setting for acute general medical experience and that the medical registrar was a key part of training. There was a significant lack of experience in both the management of medical conditions and the use of common procedures. These results highlight the challenges in general medical training and show that there is substantial room for improvement.

KEY WORDS: Training, clinical skills, after-hours care

Background

There are concerns that the quality of junior doctors’ training has deteriorated since the introduction of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD).1–6 Training structure and delivery has also been influenced by the introduction of Modernising Medical Careers (MMC), the Foundation Programme and development of new curricula by the Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board (JRCPTB). It is recognised that the traditional experiential model of training in England might no longer meet the training needs of junior doctors, given the significant reduction in working hours.6 Continuing to achieve a balance between service demands and the training needs of junior doctors is a challenge.7 Delivery of training has to adapt to current working patterns to continue to deliver high-quality training to junior doctors in England.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that core medical trainees (CTs) feel increasingly under prepared to become medical registrars by the end of CT2. Medical registrars also feel that their supervisory role is increasing owing to junior doctors being less experienced. There are potential safety concerns if medical registrars themselves are less experienced, lack confidence or do not have the time to supervise and train adequately their junior doctors as their workload increases.4,5,8

Despite the recent changes to training, there has been limited work done at a national level assessing the perspectives of medical trainees on their current training experiences. In this article, we report the results of national surveys exploring junior doctors’ views and experiences of training in general medicine.

Methods

Surveys were developed following discussion forums with Royal College of Physicians of London (RCPL) New Consultants Committee, RCPL Regional Advisors Committee, RCPL Trainees Committee, heads of schools for medicine in England, RCPL Patient Carer Network, medical registrars from the Severn deanery and representatives from RCP Edinburgh.

Three electronic surveys were distributed, using Vovici software, via email to different training groups as follows:

Medical registrars, both specialty trainee (ST3–ST7) and specialist (StR), in England and Scotland were identified from the JRCPTB database and sent a survey on 20 October 2011. Weekly reminder emails were sent for 4 weeks, after which the survey was closed and analysed.

Year 1 and year 2 CTs (CT1 and CT2) in England and Scotland were identified by the JRCPTB database and sent a survey on 23 September 2011. Fortnightly reminder emails were sent for 4 weeks, after which the survey was closed and analysed.

Foundation year (FY) 2 doctors in England were approached via the UK Foundation Programme Office (UKFPO) on 9 November 2011 and surveys were distributed at the discretion of regional foundation programme directors.

The surveys explored several themes including: enjoyment of medicine, overall satisfaction, career aspirations, deterring and attracting factors, and perceptions of the medical registrar. The full surveys are available from the RCP website (FY2 survey: www.rcpworkforce.com/se.ashx?s = 253122AC3FC24E59, CT survey: www.rcpworkforce.com/se.ashx?s = 253122AC3FC24E66, and registrar survey: www.rcpworkforce.com/se.ashx?s = 253122AC3FC24E89).

In some questions, participants were asked to reflect on their last year of training. Owing to the timing of the distribution of the surveys, FY2s were asked to reflect on their FY1 year, CT1s on their FY2 year, and CT2s on their CT1 year. In addition to the structured-answer format, participants were given some opportunities to give free-text responses.

The results from each survey were analysed individually. A subgroup analysis of CT1s and CT2s was performed within the CT survey and these data have been presented where different questions have been asked of the two groups or variations in response are noted. Descriptive statistics of the survey findings are also provided.

Results

There were a total of 212 responses from FY2 doctors in three deaneries (Severn, East Midlands and West Midlands), with a response rate of 18%. In total, 728 CTs completed surveys across all deaneries, giving a response rate of 23%.

Training settings and opportunities

Time spent in different clinical settings

All CT1 doctors had spent at least 2 months working in a general medical specialty during their FY1 year and 89% had spent 4 months or longer. Of CT1s, 72% had spent time working in a general medical specialty during their FY2 year, with most (68%) spending 4 months or longer.

Over 20% of CT1s had spent some, if not all, of their time in general medicine during their FY1 and FY2 years working supernumerary (24% and 22% respectively). One-third (32%) of CT1s had not worked any night shifts in general medicine during their FY1 year.

Two-thirds (64%) of CT1s had spent at least 1 month working on an acute care unit (medical admissions ward or emergency department) during their FY2 year, compared with 38% during their FY1 year.

Training in different clinical settings

CTs and FY2s were asked to rate how useful they found different clinical settings for ‘learning how to manage acutely unwell patients’ on a scale of 0–5 (0 = not at all useful, 5 = extremely useful).

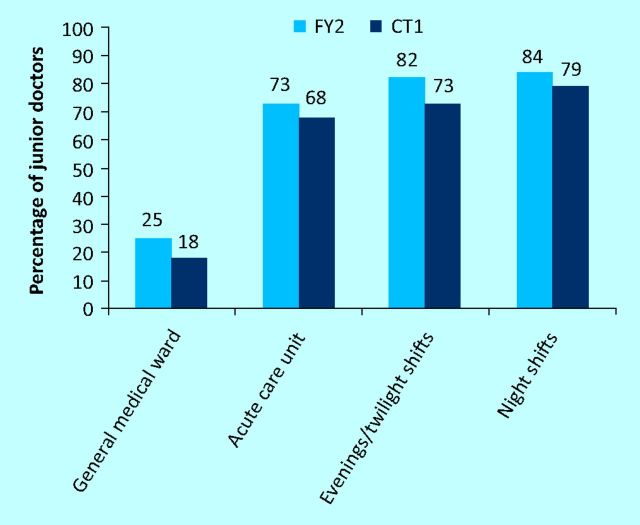

When rating normal working day shifts on a general medical inpatient ward, 25% of FY2s and 18% of CTs gave a score of ≥4/5. By contrast, 73% of FY2s and 68% of CTs scored normal working days on acute care units ≥4/5 (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Value of different clinical settings for learning how to manage patients who are acutely unwell. (Percentage of junior doctors giving a score of 4 or 5 out of 5.) CT = core medical trainee; FY = foundation year.

Across the board, FY2s, CT1 and CT2s found out-of-hours work the most useful setting for gaining this type of experience. In total, 84% of FY2s and 79% of CTs gave nightshifts a score of ≥4/5. In addition, 82% of FY2s and 73% of CTs scored evening or twilight shifts ≥4/5 (Fig 1).

Presenting to seniors ‘on-take’

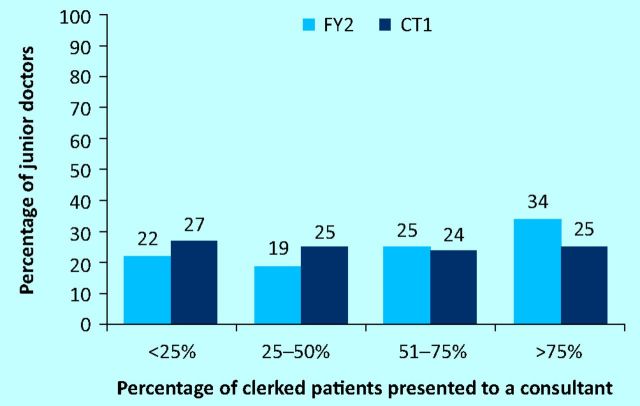

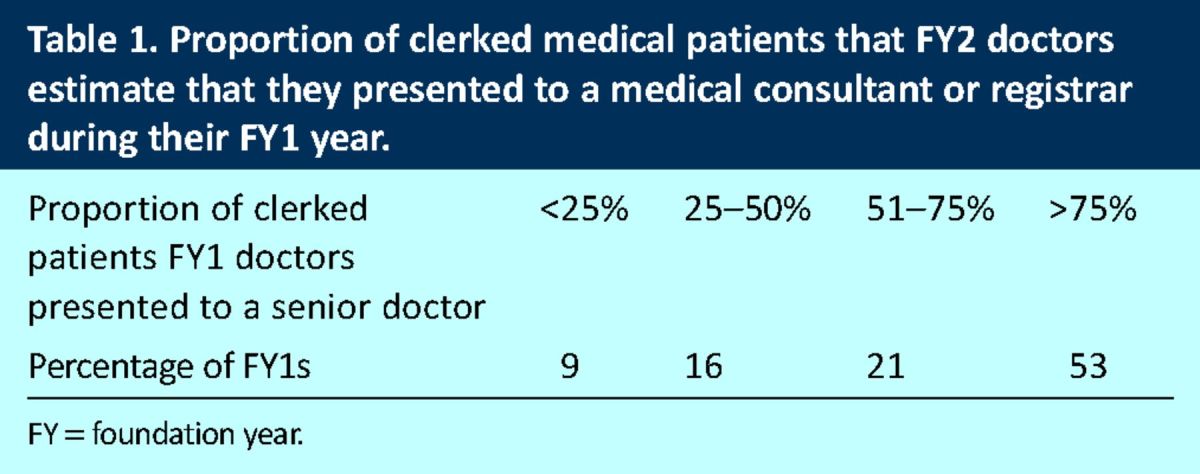

CTs were asked to estimate what proportion of the patients that they clerked ‘on-take’ they presented to a consultant, for example, on the post-take ward round (PTWR). They were asked to reflect on their previous year of training.

The results demonstrated that junior doctors’ opportunities to present to, and get feedback from, their consultants varied widely. For example, 25% of CT2s reported that they had presented over 75% of their clerked patients and 27% presented less than 25%, during their CT1 year of training. The complete results for FY2 and CT1 are shown in Fig 2.

Fig 2.

Proportion of medical patients clerked by junior doctors that they estimate they presented to a consultant, during their previous year of training. CT = core medical trainee; FY = foundation year.

The FY2s were asked to report what proportion of the medical patients that they clerked during their FY1 year they presented to either a consultant or medical registrar. The responses are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proportion of clerked medical patients that FY2 doctors estimate that they presented to a medical consultant or registrar during their FY1 year.

Clinical experience

Common medical conditions

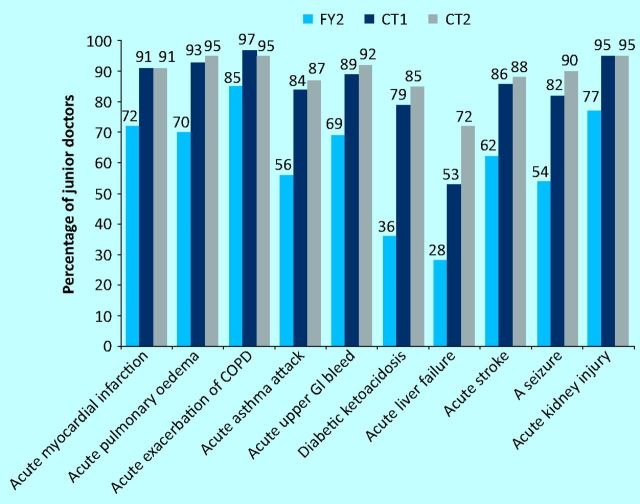

FY2s, CT1s and CT2s were asked to indicate which 10 common medical presentations they had personally diagnosed. As expected, the results demonstrated a gradual increase in exposure to common medical presentations from FY2 to CT2 (Fig 3).

91% of CT2s had diagnosed an acute myocardial infarction (MI) compared with 72% of FY2s

72% of CT2s had diagnosed acute liver failure compared with 28% of FY2s

88% of CT2s had diagnosed stroke compared with 62% of FY2s.

Fig 3.

Percentage of junior doctors who report they have ‘personally diagnosed’ common medical conditions. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT = core medical trainee; FY = foundation year; GI = gastrointestinal.

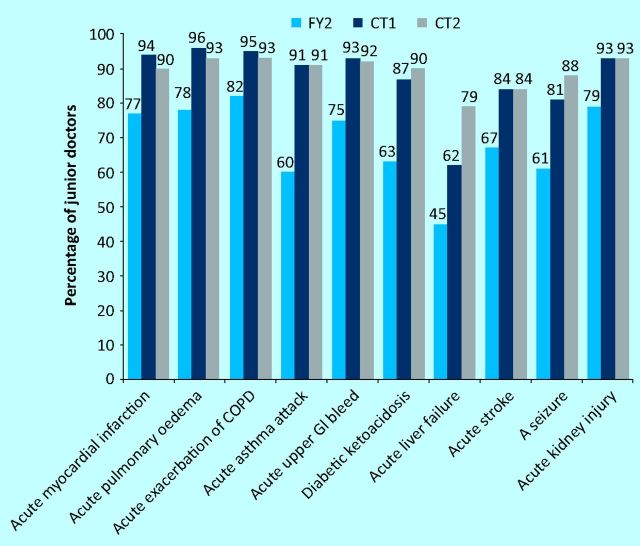

Trainees were asked to indicate which of 10 common medical conditions they had been involved in managing. By the CT2 level, most, but not all, trainees had had some experience managing all these medical conditions (Fig 4). The results comparing FY2, CT1 and CT2 experiences managing common acute medical conditions are also shown in Fig 4.

Fig 4.

Percentage of junior doctors who report they have been ‘involved in managing’ common medical conditions. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT = core medical trainee; FY = foundation year; GI = gastrointestinal.

Medical procedures

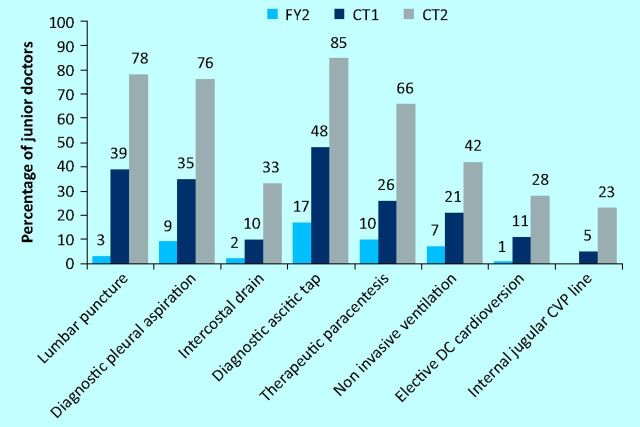

CTs and FY2s were asked to indicate their level of independence performing eight core medical procedures. CT2s are currently required to be competent performing these procedures independently to progress to ST3.

In general, FY2 doctors had had the opportunity to at least observe many of the procedures being performed. A few FY2s were independently performing core medical procedures. For example, 3% of FY2s could independently perform lumbar punctures, 17% diagnostic ascitic taps and 1.6% intercostal chest drains (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Percentage of junior doctors self-reporting as independent at performing eight common medical procedures. CT = core medical trainee; CVP = central venous pressure; DC = direct current; FY = foundation year.

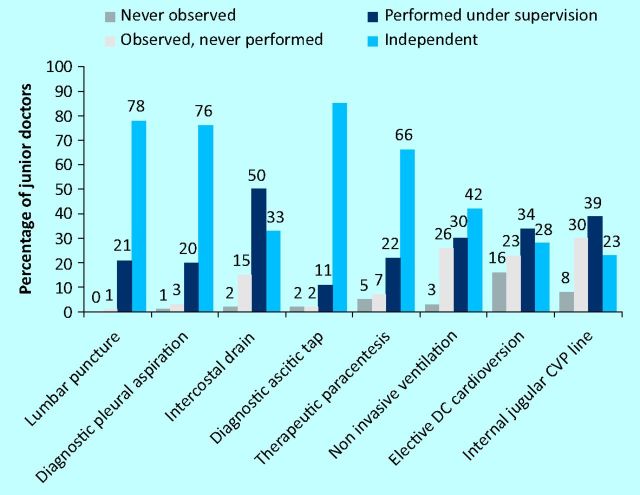

Most CT2s felt that they could independently perform lumbar punctures (77.5%), diagnostic pleural aspirations (76%), diagnostic ascitic taps (85%) and therapeutic paracentesis (66%). However, only a few trainees were independently performing intercostal drains (33%), non-invasive ventilation (41.5%), elective direct current (DC) cardioversion (27.5%) and internal jugular central venous pressure lines (23%) (Fig 5). Fig 6 shows a more detailed breakdown of the different levels of procedural independence reported by CT2s.

Fig 6.

CT2 doctors self-reported levels of independence performing eight common medical procedures. CT = core medical trainee; CVP = central venous pressure; DC = direct current.

Cardiac arrest experience

Trainees were asked about their experience participating in, or leading, cardiac arrests teams. Of FY2 doctors, 9% had never worked as a member of a resuscitation team, whereas 70% had participated in more than two cardiac arrest calls, 15% had led one cardiac arrest team and 1% had led more than two. By contrast, most CT2s (96%) had participated in five or more cardiac arrests. However, 34% had never led a resuscitation team.

Self-reported independence on the acute take

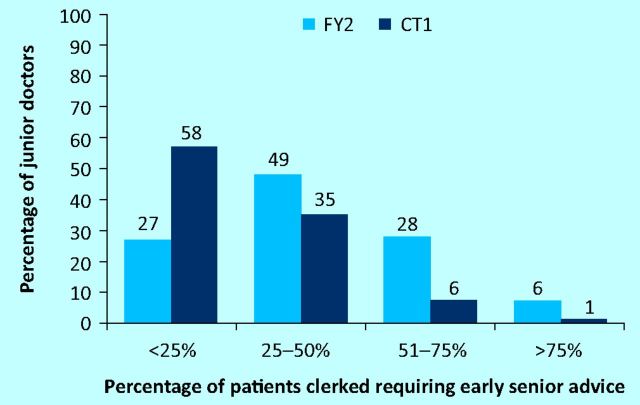

CT2s were asked: ‘On average as a CT1 doctor: what proportion of the patients that you clerked would you require early senior advice in developing your management plan (ie would not feel comfortable waiting until the next day for a post take ward round)?’ Similarly CT1s were asked to reflect on their experience during the previous year (ie FY2).

Most CT2s (58%) felt that, during their recent CT1 year, they had needed early advice for less than 25% of the patients that they clerked, 35% felt they had needed early advice for between 25% and 50% of all patients.

During FY2, 48% had needed early advice for between 25% and 50% of the patients that they clerked and 18% needed early advice for between 50% and 75% of patients. The results are shown in Fig 7.

Fig 7.

Proportion of clerked medical patients that CT1 and CT2 doctors estimate that they required early senior advice for developing their management plan, during their previous year of training (ie as FY2 and CT1s respectively). CT = core medical trainee; FY = foundation year.

This question was not asked of FY2s because there is an expectation that all FY1s receive early support developing their management plans on the acute take.

Free-text comments

During the survey, there were opportunities for trainees to add free-text comments. There were many emotive and powerful comments made. There were a few recurrent themes related to training issues and representative examples are given below.

Positive comments regarding effectiveness of medical training:

‘Having worked as a CT1 and CT2 the prospect [of becoming a medical registrar] doesn't scare/deter me as much as it once did’ (CT2)

‘ . . . enjoyed my medical rotation because it felt like the backbone of medicine as a career . . .’ (CT1)

Reflections on the types of training and/or settings that they found most beneficial:

‘ . . . placement on medical assessment unit particularly beneficial in developing examination/clinical skills as well as acute management.’ (CT1)

‘Ward cover nights were where I learnt a lot of medicine and independence’ (CT1)

‘Not doing on calls as medical house officer I think is a huge loss from training’ (CT1)

Many trainees commented on how they felt training could be improved, with the length of training being a common theme:

‘I think SHO training should be longer, with more emphasis on clinical experience’ (CT1)

‘I think there should be a position between SHO and StR . . . support them whilst gradually stepping into the role.’ (CT1)

‘With the current system coming to fruition the medical registrar will be much less experienced and thus more likely to be unable to competently undertake the role of medical registrar’ (CT2)

‘I would like to have another years training before I have to take this responsibility’ (CT2)

Many commented on how well they felt training would prepare them for becoming the on-call medical registrar:

‘I feel the level of knowledge and experience I have will not be good enough in 2 years time making the prospect frightening, bordering on dangerous’ (CT1)

‘The idea of becoming a medical registrar fills me with dread. I am no way near ready to take on the responsibility of managing severely unwell patients’ (CT2)

‘I feel underprepared to deal with the challenges of being a medical registrar on call’ (CT2)

‘. . . level of exposure to sick patients and experience in procedures would make it unsafe to be a medical StR’ (CT2)

Discussion

Early, good-quality training in the recognition and management of acute illness is vital for all junior doctors and is, appropriately, the major focus of the Foundation Programme curriculum.7 The impact of European Working Time Directive (EWTD) is perceived to have been greatest in specialties with high emergency and/or out-of-hours work.6 Medical on calls and night shifts, in particular, are perceived by junior doctors in these surveys to be the most useful clinical setting to learn how to manage patients who are acutely unwell. Despite this, a significant proportion (32%) of FY1 doctors do not work any medical nights and 24% work supernumerary during medical rotations. Therefore, they do not benefit from evening and/or twilight on-call experiences either. The results indicate that a proportion of junior doctors might never do medical nights during their FY1 or FY2 years.

PTWRs provide an ideal opportunity for effective feedback and supervision; both of these are important for junior doctors’ training, confidence and ability to cope with clinical duties.5,9,10 In the Annual RCPL Registrar Survey 2011, 96% of medical registrars felt that reviewing new admissions that they had assessed on ‘the take’ with a consultant was important for their training.11 The Temple report, Time for Training, highlights the importance of using learning opportunities in every clinical situation.6 Yet, in recent years, junior doctors have increasingly struggled to attend PTWRs10 and consider that they receive inadequate feedback9. Disparity in training opportunities is shown in these surveys by the wide differences in the proportion of patients that trainees present to seniors on the PTWR.

Inconsistencies in training opportunities such as these will result in trainees entering CT with different levels of experience and confidence assessing and managing patients who are acutely unwell. Lack of clinical experience among FY doctors risks discouraging them from applying for CT and contributes to the fear of being the medical registrar, as supported by some free-text comments.

Many of the CT2 doctors surveyed will be progressing to become the on-call general medical registrar soon. In this role, they will be expected to give advice on managing complex medical cases, independently perform potentially difficult emergency procedures and be competent decision makers at cardiac arrest calls. It is important to ensure that FY1/2 and CT years adequately prepare junior doctors for this next step in their careers. Junior doctors’ hours have been reduced, the PTWR structure is changing and there is some evidence that the number of cases trainees see during an on-call shift is reducing.12 Therefore, it is important to assess whether medical trainees are continuing to get sufficient exposure to a range of clinical conditions and opportunities to perform procedures.

Most CT2s reported experience diagnosing and managing the core medical presentations selected for the purpose of this survey. However, a few reported that they have never managed an acute MI (10%) or diabetic ketoacidosis (11%). It is important to recognise that this experience does not necessarily equate to competence; neither has this survey assessed junior doctors’ exposure to more unusual conditions.

The results suggest that many CT2s will struggle to get the procedural experience that they require to progress to ST3. This is a result of a combination of factors, including fewer working hours, fewer teaching opportunities during busy shifts,4,5 fewer procedures being done, especially out of hours, and those that are done are increasingly being performed by specialists.

Given that this is the first survey of its type, with no data from previous years for comparison, it is difficult to know how to interpret the data. They might not reflect any decline in clinical experience compared with previous ‘pre-EWTD’ years. However, anecdotal evidence at all levels suggests that medical trainees are generally less experienced. Assessments are appropriately increasingly competency based, but consideration needs to be given to the length, structure and methods of training to ensure that junior doctors can achieve the necessary competencies.6,12,13,14

These surveys are part of a larger study being carried out by the RCP Medical Workforce Unit looking at patient safety and the role of the on-call medical registrar. The workload of the medical registrar is increasing, especially out of hours.8

These results support the anecdotal evidence that medical registrars have a significant, and increasing, supervisory responsibility. As well as providing early reviews of all FY1 clerkings, a significant proportion of FY2s and CTs also require early senior advice about their patients. Few medical trainees are independently performing procedures, further adding to the workload of the medical registrar. FY1s are increasingly being taken off ‘nights’ and there are a significant number of supernumerary posts in the foundation years. Therefore, FY2s, and some CT1s, have limited experience working out of hours and managing patients who are acutely unwell.

These increasing supervisory demands need to be fulfilled by the medical registrar while still providing leadership to ‘the take’ and medical wards, support to non-medical specialties (including surgery, emergency departments and general practitioners) and managing patients who are acutely unwell and/or with complex medical needs. There are concerns that medical registrars are struggling to meet the growing demands on their time. Ensuring that they can provide adequate supervision to junior doctors out of hours is particularly important with regard to patient safety. Concerns regarding supervision of junior doctors out of hours are highlighted in the Temple report, Time for Training.6 Additionally, the Collins report, An Evaluation of the Foundation Programme, found that trainees feel that they are being asked to practice beyond their level of competence and without adequate levels of supervision.7 It is important to keep sight of the increasing demands on the medical registrar so that patient safety can be ensured.

These surveys provide a unique insight into current training experiences of junior doctors working in medical specialties. It highlights some inconsistencies in training opportunities and indicates the types of training setting that junior doctors find useful. Areas where many trainees are struggling to get sufficient experience are identified, in particular procedural skills.

References

- 1.Lancet Doctors’ training and the European Working Time Directive. Lancet 2010;375:2121. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60977-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson R. A response to Cappuccio F et al. ‘Implementing a 48h EWTD-compliant rota for junior doctors in the UK does not compromise patients’ safety: assessor blind pilot comparison’. QJM 2009;102:297–8. 10.1093/qjmed/hcp017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.British Medical Association BMA Survey of members views on the European Working Time Directive – Final Report. London: BMA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scallan S. Education and the working patterns of junior doctors in the UK: a review of the literature. Med Educ 2003;37:907–12. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01631.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derrick S, Badger B, Chandler J, et al. The training/service continuum: exploring the training/service balance of senior house officer activities. Med Educ 2006;40:355–62. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temple J. Time for training: a review of the impact of the European Working Time Directive on the quality of training. London: Medical Education England, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins J. Foundation for excellence: an evaluation of the foundation programme. London: Medical Education England, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodgson H. Let's hear it for the medical registrar! Clin Med 2011;6:515–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin PJ, Newton RW, Buckley G, et al. Senior house officers in medicine: postal survey of training and work experience. BMJ 1997;314:740–3. 10.1136/bmj.314.7082.740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaponda M, Borra M, Beeching NJ, et al. The value of the post-take ward round: are new working patterns compromising junior doctor education? Clin Med 2009;9:323–6. 10.7861/clinmedicine.9-4-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goddard AF, Chaudhuri E, Mason NC. Medical registrars in 2011: annual medical registrar survey. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearse RM, Mitra AV, Heymann TD. What the SHO really does. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1999;33:553–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenhard A, Moallem M, Marrie RA, et al. An intervention to improve procedure education for internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:288–93. 10.1007/s11606-008-0513-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr SJ. Assessing clinical competency in medical senior house officers: how and why should we do it? Postgrad Med J 2004;80:63–6. 10.1136/pmj.2003.011718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]