ABSTRACT

This paper reviews procedures for ensuring that physicians in the European Union (EU) continue to meet criteria for registration and the implications of these procedures for cross-border movement of health professionals following implementation of the 2005/36/EC Directive on professional qualifications. A questionnaire was completed by key informants in 10 EU member states, supplemented by a review of peer-reviewed and grey literature and a review conducted by key experts in each country. The questionnaire covered three aspects: actors involved in processes for ensuring continued adherence to standards for registration and/or licencing (such as revalidation), including their roles and functions; the processes involved, including continuing professional development (CPD) and/or continuing medical education (CME); and contextual factors, particularly those impacting professional mobility. All countries included in the study view CPD/CME as one mechanism to demonstrate that doctors continue to meet key standards. Although regulatory bodies in a few countries have established explicit systems of ensuring continued competence, at least for some doctors (in Belgium, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Slovenia and the UK), self-regulation is considered sufficient to ensure that physicians are up to date and fit to practice in others (Austria, Finland, Estonia and Spain). Formal systems vary greatly in their rationale, structure, and coverage. Whereas in Germany, Hungary and Slovenia, systems are exclusively focused on CPD/CME, the Netherlands also includes peer review and minimum activity thresholds. Belgium and the UK have developed more complex mechanisms, comprising a review of complaints or compliments on performance and (in the UK) colleague and patient questionnaires. Systems for ensuring that doctors continue to meet criteria for registration and licencing across the EU are complex and inconsistent. Participation in CPD/CME is only one aspect of maintaining professional competence but it is the only one common to all countries. Thus, there is a need to bring clarity to this confused landscape.

KEYWORDS: Revalidation, licencing, registration, quality of care, EU, professional mobility, maintaining competence

Introduction

Since coming into force in 2007, the Directive of the European Union (EU) on the recognition of professional qualifications1 has simplified the processes facing health professionals moving within the EU for work. The resulting increase in professional mobility has led to concerns about whether they all have adequate skills and expertise. Although European law sets out basic standards for initial medical training, it has so far been silent on the retention of skills and acquisition of new ones to reflect changing medical practice over a professional lifetime. This has led to calls for physicians seeking to practice in a different country to be required to demonstrate that they have maintained an appropriate level of professional competence, for example by participating in continuing professional education and training. However, as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) and others have noted,2,3 support for greater professional mobility has not been matched by a similar interest in measures to ensure that health professionals remain fit to practice.

Mechanisms to assess professional standards vary across European countries and health professions.4 Cultural and institutional factors have an important role in shaping these mechanisms, including the degree to which it is deemed legitimate for governments or other authorities to be involved in professional regulation.5 Authorities, which might be state, para-state, or professional, do expect at least some physicians to participate in some form of continuing medical education (CME) or continuing professional development (CPD), but only few make participation mandatory.

CME refers to participation in medical education and training with the purpose of keeping up to date with medical knowledge and clinical developments, whereas CPD is a broader concept including CME along with the development of personal, social and managerial skills.4 However, as with many aspects of professional regulation, in practice, if not in theory, the terms are often used interchangeably;6 therefore, here we treat CPD and CME as being essentially the same.

The overall structure of schemes for actively maintaining professional competence, the rationale behind CPD/CME and the range of actors involved differ markedly, depending in part on the mechanisms that confer or remove a physician's right to practice. In some countries, licensing and/or registration (again terms that have different meanings in different countries and both being used in different settings to explain the same processes) is indefinite, whereas in others it is time limited and requires periodic relicensing and/or reregistration,7 either by means of a simple reapplication or based on more formal requirements of demonstrating fitness to practice. In both instances, professional misbehaviour and crimes can lead to a premature end of the license, although as we have shown elsewhere, the criteria for removal also vary markedly.8

The term ‘revalidation’, although only used officially in the UK, has come to describe a process to ‘demonstrate that the competence of doctors is acceptable’ and can encompass several elements, such as CPD/CME, peer review and external inspection.4 Here, we update our previous review of revalidation and related systems in the EU,4 focusing on the implications for policy in light of the newly enacted Directive to ‘modernise’ the regulation of professional qualifications in Europe1 and looking at processes in place to actively maintain professional competence in 10 European countries. This is the second part in a series exploring professional standards across Europe and follows our work on licensing and registration processes.7

Methods

Data collection

A questionnaire was designed for self-completion by key informants with knowledge of national regulatory systems in 10 EU member states (Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain and UK). It addressed issues pertaining to the definition and purpose of revalidation (as defined above) as well as details of the assessment process and its participants. Respondents were identified through health research and policy networks, and by direct contact with ministries of health and professional bodies. There was at least one respondent from each country. The information collected from the experts was supplemented by and triangulated with data from peer-reviewed and grey literature. In May 2014, the paper was sent to experts in each country to check that the information obtained was accurate and up to date.

Analytical framework

The framework used was based on the model of policy analysis presented by Walt and Gilson in their seminal 1994 publication.9 This model links four elements: the substantive content of the policy; the actors involved; the processes of formulation and development; and contextual factors framing the policy. These components were adapted to fit the purpose of the analysis (Box 1).

Box 1. Analytical framework9

Results

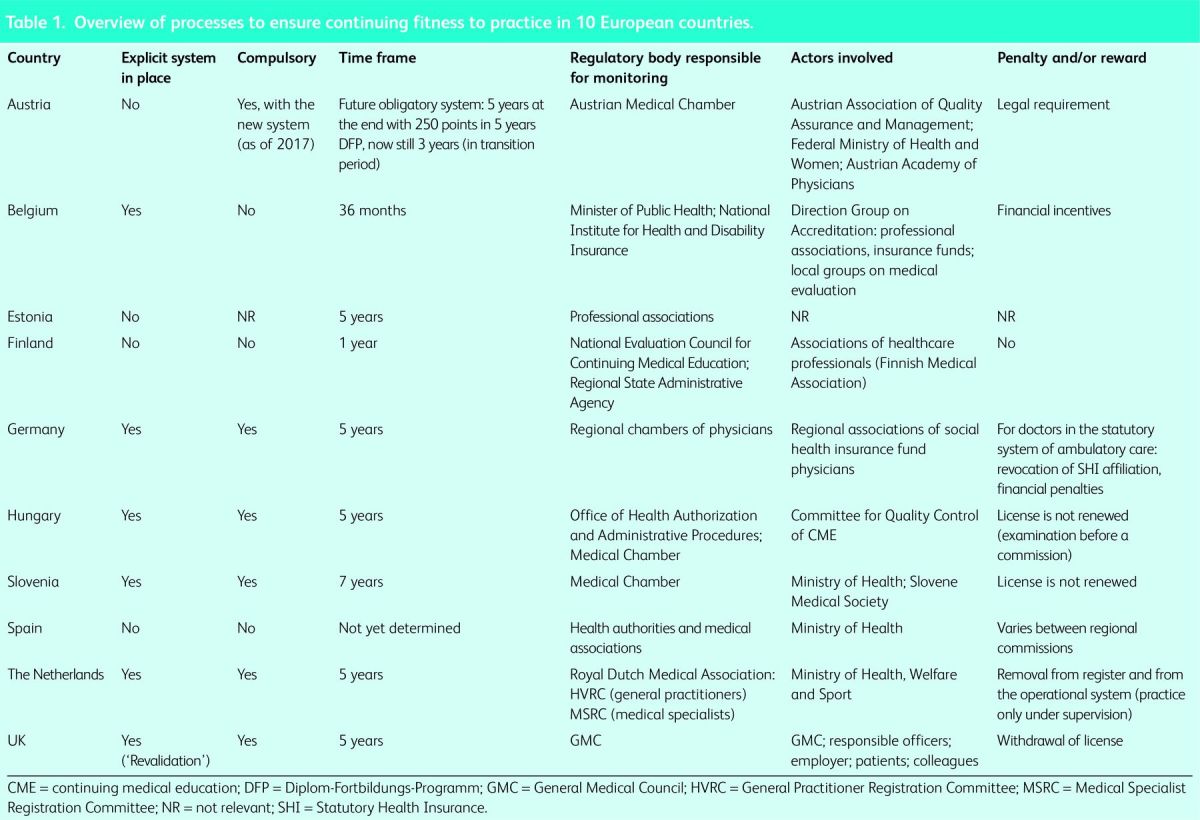

An overview of information on practices to ensure continuing fitness to practice among participating countries is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of processes to ensure continuing fitness to practice in 10 European countries.

Definition and contents

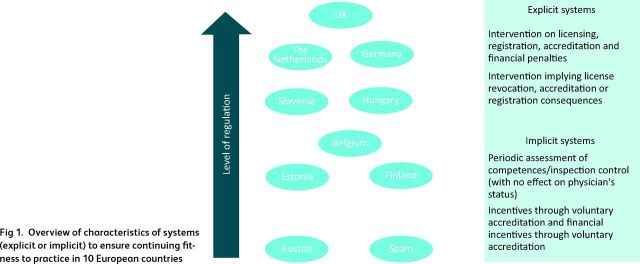

Systems designed to ensure that physicians remain competent exist in all countries and can be categorised as more or less regulated, based on the degree of intervention by governments or regulatory bodies (Fig 1). Similarly, participation in CPD and CME is required everywhere, for at least some physicians, and to some extent. There seems to be widespread acceptance that it offers a mechanism that can have a role in ensuring that basic standards of care do not fall below acceptable levels and, in some cases, promoting continuing improvement of quality of care.10,11

Fig 1.

Overview of characteristics of systems (explicit or implicit) to ensure continuing fitness to practice in 10 European countries

In some countries, it is the responsibility of individual physicians to ensure that they are up to date and fit to practice, as in Austria, Finland, Estonia, Spain and Germany (the latter only for specialists working in hospitals), whereas a few countries have introduced more formalised requirements to demonstrate continued competence. However, the system in the UK is unique in its scope and coverage, comprising all registered medical practitioners, including those with no patient contact. In other countries, only physicians undertaking certain roles must show that they continue to meet certain criteria. For example, in Germany only physicians working in ambulatory care and contracted with the social health insurance system must do this.

However, even where such approaches exist, they are far from homogeneous either in their rationale or structure (Table 1). In Germany, Hungary and Slovenia, it is sufficient to provide evidence of undertaking CPD/CME, whereas in the Netherlands, the process also includes peer review (visitatie) and evidence of undertaking a minimum level of professional activity. In Belgium, a review of complaints or compliments on performance is included. However, again, it is the UK that has the most comprehensive assessment. All physicians, regardless of their activities, must undergo detailed annual appraisals that include surveys of colleagues and patients, a review of compliments and complaints, and demonstration of participation in approved CPD. The model is adapted, with varying degrees of success, for those physicians with no patient contact.

Actors involved, including their roles and functions

Given the complexity of the systems, it is not surprising that more than one type of institution is often involved. The range of participating actors differs widely and there is no agreement on which bodies are counterparts of each other in different countries. Each has a particular mix of responsibilities, which can include the maintenance of a register, professional standards, production of guidelines, determination of the right to practice (or in some cases to contract with social insurance funds, so that practitioners not holding contracts with the funds are excluded from their remit), and organisation of CPD and CME activities (Table 1).

The diversity of bodies involved in these processes reflects the different approaches to regulating the medical profession in general (Table 1). Frequently, professional associations have an important role in CPD/CME, as in Belgium and the Netherlands, where they accredit activities. In Germany, physicians’ chambers at a regional level monitor participation by their members in CPD/CME activities. The Slovenian Medical Chamber accredits activities proposed by various CPD/CME organisers, whereas in Hungary, professional associations only review the programmes offered by universities and hospitals. In the UK, the Royal Colleges oversee CPD/CME. However, there are some exceptions. In Spain, a special body was created for this specific purpose (Spanish Accreditation Council for CME), and Austria has the Austrian Association of Quality Assurance and Management).

Processes of demonstrating continuing adherence to standards

Two main systems can be distinguished: those based merely on an expectation that one will maintain competence without the need to comply with explicit standards; and those that require continued competence to be demonstrated formally.

Implicit systems

These are found in Spain, Austria, Finland and Estonia. Here, CPD/CME is the cornerstone of maintaining professional competence. Accountability for participation can vary according to employment status. For example, in Austria, physicians in private practice are obliged to participate in self-evaluation monitored by the Austrian Association of Quality Assurance and Management, whereas those employed in public hospitals are accountable to their employers. These systems are being replaced and, from 2017, the Austrian Medical Chamber will be obliged to reveal to the Government every 2 years those physicians that have successfully accumulated sufficient CPD/CME points.

The Spanish Government is contemplating a formal system of revalidation but at present participation in CPD/CME is only monitored if it is part of an employment contract, although there are also financial incentives in place to encourage it.

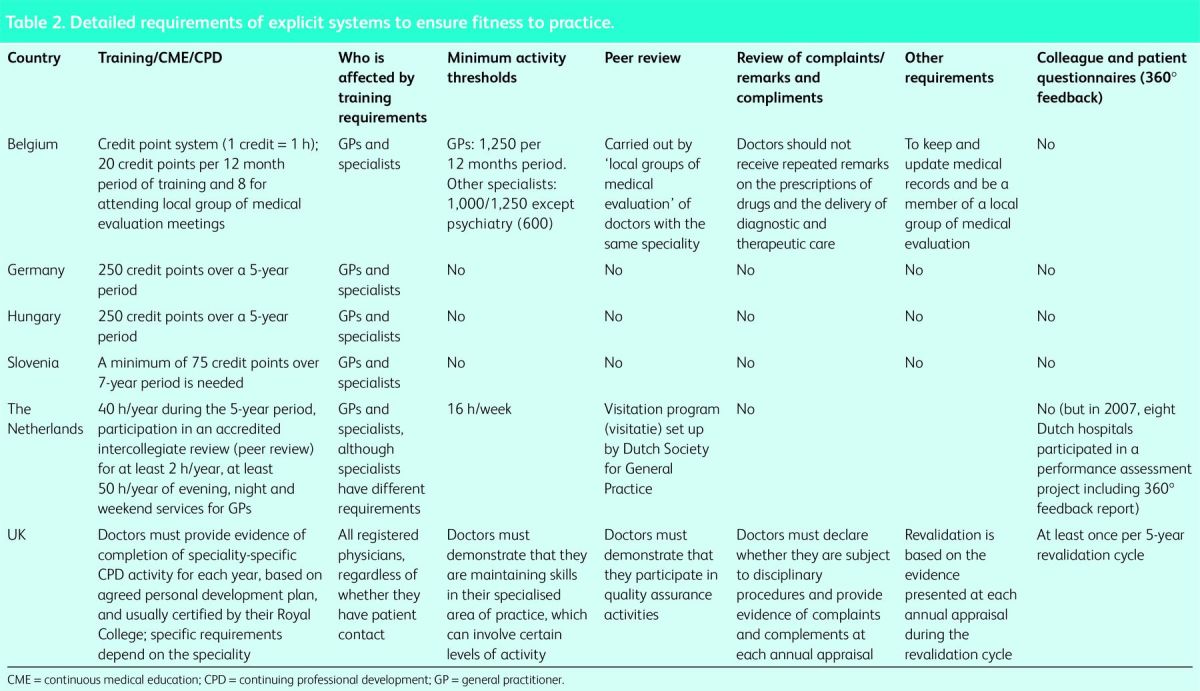

Explicit systems

These are seen in Belgium, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Slovenia and the UK. Each requires explicit demonstration of continued competence in a defined period of time, with monitoring, and failure to fulfil requirements has consequences for the right to practice (Table 2). These consequences can involve removal of a licence to practice (eg UK) or to contract with social insurance funds (Germany). These systems can also include incentives, as in Belgium, where doctors can receive increased fees and one-off payments, and can earn as much €15,000 when participating in voluntary CPD/DME. In some cases, it is a strictly administrative process that requires only the demonstration that the doctor has participated in CPD/CME and does not include any patient or employer input (eg Germany and Slovenia). In Hungary, the role of employers extends only to the provision of certain documentation on practice. In others, peer and/or employer and patient input are vital to the revalidation process (eg the Netherlands and the UK).

Table 2.

Detailed requirements of explicit systems to ensure fitness to practice.

There are marked differences with regard both to the consequences of noncompliance and the components and degree of freedom of choice within formal systems. In Germany, a medical license is valid for life unless withdrawn for malpractice or similar behaviour. However, ambulatory-care physicians contracted by the statutory health insurance system who do not comply with CPD/CME are subject to temporary revocation of their social health insurance affiliation or financial penalties and reprimands. By contrast, in Slovenia and Hungary, each physician treating patients must demonstrate participation in CPD/CME to hold a license. As described above, this is also the case in the UK, although with many additional requirements. Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, all doctors providing patient care are required to reregister every 5 years; to qualify, applicants must fulfil several formal requirements, including CME/CPD, minimum levels of professional activity and peer-review, or face either individual training programmes or removal from the register.

In Germany and Slovenia, physicians are free to choose the type of CPD/CME as well as the specific course that they wish to attend; however, the events must be approved by the regional chamber of physicians. Each validated event is allocated a certain number of points and physicians must collect a specified total number within a given timeframe, regardless of which events they choose to participate in. While the same number of points need to be collected in Hungary as in Germany (250 every 5 years), here the approach is more structured: 50 points should ideally be collected for each year of the five-year period.

As noted above, the revalidation arrangements in the UK are unique. Physicians must explicitly demonstrate that they meet a set of criteria contained in the General Medical Council's guidance on Good Medical Practice Framework12 in an annual appraisal. This includes confirmation from a professional association that they have met set criteria for participation in CPD, whereby what they undertake must map onto a previously agreed personal development plan. Each 5 years, they must also provide documentary evidence of a survey of patients (or other group of broadly comparable individuals with whom they interact, clearly a problem for pathologists), as well as undergoing a 360° appraisal in which those above, below and at the same level are asked, anonymously, to rate them. They must then provide these extensive portfolios of evidence to a responsible officer, appointed by the General Medical Council, who will determine whether they should be revalidated. If not, they will remain on the medical register but lose their licence to practice.

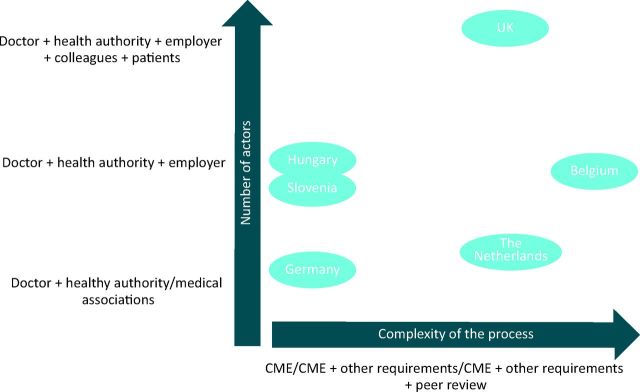

It is clear from the elements described above that explicit systems differ greatly with regard to their complexity and components. A mapping of each system based on its main characteristics can be seen in Fig 2.

Fig 2.

Overview of complexity and number of actors to ensure continuing fitness to practice in 10 European countries. CME = continuing medical education.

Contextual factors to the policies, particularly those impacting professional mobility

EU law

Since 1974, successive Directives have provided for mobility of physicians within the European Economic Communities (subsequently the EU). Over time, these have made the process of movement easier, while taking account of some of the factors that distinguish medical practice from other occupations. The most recent Directive on professional qualifications, adopted in 2005 (2005/36/EC), is now being amended in a process that addresses all professional qualifications, and not only for medicine. A revised text was accepted by the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers in October and November 2013, respectively.13 The most recent changes reflect what has been a persisting concern about the need to balance easier mobility for health professionals with assurance that the quality and safety of care provided to patients are not jeopardised. The proposed revision to the Directive includes a requirement for regulatory authorities proactively to notify their counterparts in other member states about doctors whom they deem unfit to practice. It will also change the basis of mutual recognition of qualifications from the duration of instruction to the acquisition of knowledge, skills and competences, give regulators the power to test language skills (proportionately) after recognition of the qualification obtained abroad but before practice is permitted, and require member states to encourage continuing professional education and training.

National legislative and regulatory norms

In some countries, the regulation of the medical profession is seen as a ‘private’ issue between patient and doctor, based on trust in adherence to professional standards, with only minimal involvement by the regulatory authorities. In others, the state assumes the primary responsibility for regulation, either directly or by delegating it to quasi-state bodies or professional bodies acting within a clear legal framework. In this way, the exercise of the medical profession is seen as a ‘public’ issue, demanding public accountability. However, as the shift away from self-regulation in the UK shows, these norms can change.

Discussion

Measures to demonstrate continuing competence are important where there is professional mobility. However, the diversity within the EU, as with all aspects of professional regulation, is enormous and there is not even any agreement about basic terminology. Even if such an agreement about terminology could be achieved, it will not be easy to achieve consensus about its contents. As noted above, there are different views about the legitimate role of the state in regulating professions. The UK is an outlier in this regard, going far beyond that seen in any other country. This reflects more fundamental differences in how to balance the power of the state and the individual, something exemplified by the very different reactions in the UK and continental Europe to revelations by Edward Snowden of mass surveillance of the population by intelligence agencies. These differences have strong historical roots, derived from the different national experiences in the 20th century.

A difficulty in moving ahead is the lack of clear evidence about which model is best.14 Although there are clear theoretical benefits from the extremely detailed model adopted by the UK, as commentators have noted,15 it is far from clear whether it would identify another Harold Shipman, a doctor who murdered several of his patients, instead offering ‘an illusion of protection’. Moreover, the direct and indirect costs are considerable for this uncertain benefit. A further concern is that overzealous regulation could erode trust.16

This research has served to highlight that systems to demonstrate continuing competence of doctors in Europe are inconsistent in scope, coverage, and content. The newly adopted Directive 2005/36/EC provides a basis for member states to explore areas where they might reach agreement, which would usefully begin with shared terminology. However, given the diversity of national health systems and views on professions, it might not be a good idea to be overambitious.

Funding

This paper is the result of research that was requested by the European Commission's Directorate-General for Health and Consumers and co-funded through the FP7 Cooperation Work Programme: Health of the EU (contract number 242058; contract acronym EUCBCC). The European Commission is not responsible for the content of the paper. Responsibility for the facts described in the report and the views expressed rests entirely with the authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank all questionnaire respondents who took time to provide us generously with the requested information. We particularly wish to thank all the institutions participating in the study (LSE Health (the UK), European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (Belgium), Observatorie Social Europeé (Belgium), Technische Universität Berlin (Germany), Maastricht University (The Netherlands), European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research (Austria), National Institute of Public Health (Slovenia), Universitat de Barcelona (Spain), PRAXIS Center for Policy Studies (Estonia), National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (Finland), Semmelweis University, and Health Services Management Training Centre (Hungary)) for their review to assure that the terminology being adopted and the formulation of questions would be transferrable to all country settings and for collecting the data presented in this paper. We are also thankful to the professionals who took the time to review the manuscript and add comments and suggestions: Carl Steylaerts (Belgium), Rita Baeten (Belgium), Irene Glinos (Belgium) Edmond Girasek (Hungary), Nándor Rikker (Hungary), Eszter Kovács (Hungary), Andrea Schmidt (Austria), Christian Claus Schiller (Austria), Eva Turk (Slovenia), Virginia Santiago (Spain), Berenguer Camps (Spain), Ignasi Pidevall (Spain), Sietse Wieringa (the Netherlands), Nigel Sparrow (the UK) and Luisa Petigrew (the UK).

References

- 1.European Commission Directive 2005/36/EC on the recognition of professional qualifications. Off J EU 2005;255:22–143. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians Consultation on the EU Professional Qualifications Directive: response from the Royal College of Physicians. London: RCP, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legido-Quigley H, McKee M, Nolte E. Assuring the quality of health care in the European Union. Brussels: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merkur S, Mossialos E, Long M, et al. Physician revalidation in Europe. Clin Med 2008;8:371–6. 10.7861/clinmedicine.8-4-371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertilsson M. The welfare state, the professions and citizens. In: McKevitt D, Lawton A. (eds), Public sector management: theory, critique and practice. London: Sage, 1994:237–49. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peck C, McCall M, McLaren B, Rotem T. Continuing medical education and continuing -professional development: international comparisons. BMJ 2000;320:432–5. 10.1136/bmj.320.7232.432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovacs E, Schmidt AE, Szocska G, et al. Registration and licensing processes of medical doctors in the European Union. Clin Med 2014;14:229–38. 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-3-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Risso-Gill I, Legido-Quigley H, Panteli D, Mckee M. Assessing the role of regulatory bodies in managing health professional issues and errors in Europe. Int J Qual Health Care 2014;26:348–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzu036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan 1994;9:353–70. 10.1093/heapol/9.4.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherland K, Leatherman S. Does certification improve medical standards. BMJ 2006;333:439–41. 10.1136/bmj.38933.377824.802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brennan TA, Horwitz RI, Duffy FD, Cassel CK, Goode LD, Lipner RS. The role of physician specialty board certification status in the quality movement. JAMA 2004;292:1038–43. 10.1001/jama.292.9.1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.General Medical Council Good medical practice: guidance for doctors (updated). London: GMC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council of the European Union Adoption of the Professional Qualifications Directive, 16262/13. 15 November 2013. Brussels: European Council, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown CA, Belfield CR, Field SJ. Cost effectiveness of continuing professional development in health care: a critical review of the evidence. BMJ 2002;324:652–5. 10.1136/bmj.324.7338.652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakhani M. A way forward. BMJ 2005;330:1326–8. 10.1136/bmj.330.7503.1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neill O. A question of trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]