ABSTRACT

An 85-year-old man presented to hospital as an emergency having difficulties with swallowing and speech. In the emergency department, he was assessed as having acute onset dysphagia and dysarthria in keeping with an acute stroke. Subsequently, it became apparent that although the symptoms were indeed of relatively acute onset, there was a clear description by the patient of fatigability and diurnal variation, prompting a working clinical diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. The patient followed a turbulent clinical course, and interpretation of investigation results proved not to be straightforward in the acute setting. Myasthenia gravis is an uncommon disorder but it is more common in the elderly. This case provides key learning points, particularly highlighting the value of prompt, accurate clinical assessment and the importance of adhering to the clinical diagnostic formulation.

KEYWORDS: Stroke mimic, myasthenia gravis, acute neurology, clinical history

Learning points.

Acute neurology input is valuable in the stroke unit

Differentiation of stroke from mimic on the basis of history is straightforwardqInterpretation of investigations such as EMG and CSF is not straightforward

CSF protein elevation can be multifactorial; in this case, it was presumably attributable to a combination of lumbar spine disease and cerebral small vessel disease

Adherence to clinical diagnostic formulation is important

Case presentation

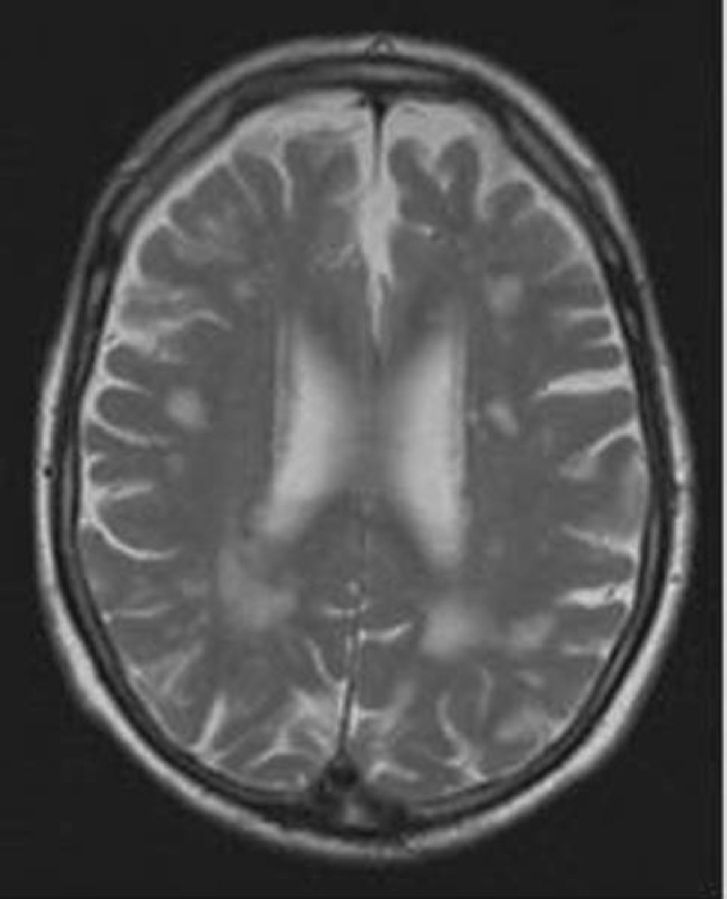

An 85-year-old man presented to hospital as an emergency having difficulties with swallowing and speech. In the emergency department, he was assessed as having acute onset dysphagia and dysarthria in keeping with an acute stroke. He had first developed symptoms 3 days earlier. No other neurological deficit was recorded. General examination was otherwise unremarkable. He had no other significant past medical history. A chest X-ray showed only a small right-sided pleural effusion. He was transferred to the stroke unit and had a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scan undertaken on an urgent basis (Fig 1). The MRI (including a negative diffusion weighted imaging study) showed diffuse white matter high signal changes in keeping with cerebral small vessel disease, with no evidence of acute infarction in the anterior or posterior circulation territories.

Fig 1.

Axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging showing multiple periventricular and deep white matter high signal foci with early confluence.

The next day (4 days after the onset of symptoms), the patient was seen on the stroke unit by a consultant neurologist (HE). Although the dysphagia was indeed of relatively acute onset, the patient clearly described fatiguability and diurnal variation. He described dysphagia of only a few days’ duration that had clearly worsened over the 24 to 48 hours preceding admission. He mentioned that the difficulty in eating was more apparent towards the end of the day, and that he had had particular difficulties during one meal while eating a meat pie. He had found swallowing to be easier again when eating breakfast the next morning. Similarly, he commented that his family had noticed in recent days that his speech became progressively more slurred the longer he spoke. Neurological examination did not reveal any additional features: there was no fatiguable weakness of extraocular movements, nor any limb fatiguability. The initial neurological working diagnosis was of bulbar myasthenia gravis (MG). Acetylcholine receptor antibodies were requested.

What was the differential diagnosis and the most likely diagnosis?

Against a diagnosis of stroke, which is a clinical syndrome characterised by focal neurological deficit(s) of sudden onset, is the fact that the symptoms of dysphagia and dysarthria showed fatiguability and diurnal variation, clinical features that are considered hallmarks of MG. On clinical grounds, this was the most likely diagnosis.

Bulbar involvement can occur early in Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) – particularly the pharyngeal–cervical–brachial variant, so this also had to be borne in mind as a differential diagnosis. An apparently acute presentation of bulbar or pseudobulbar failure can also be seen when the clinical presentations of motor neurone disease are delayed, but there were no other features on examination to support this diagnosis.

Structural brainstem lesions (such as syringobulbia) had already been excluded by the MRI brain scan. Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), despite its name, is not usually characterised by fatiguability and does not often produce dysarthria. LEMS was therefore not considered to be a likely diagnosis, and subsequent investigation results also strongly suggested that this was not a case of LEMS.

What was the initial management?

The patient was kept nil by mouth pending electromyography (EMG). A 10 French nasogastric (NG) tube was passed to 56 cm, with aspirate pH 3.0. NG feeding was commenced. Overnight, he became increasingly short of breath. He had a sinus tachycardia rate of 124 beats/minute, bilateral coarse respiratory sounds, and a fall in forced vital capacity (FVC) to 1.04 l from 2.16 l 3 hours earlier. A 12-lead electrocardiogram showed ST segment depression in leads V3 to V5. Troponin T was elevated at 42 ng/l (normal range 0–14 ng/l), although this fell to 33 ng/l within the next 8 hours, with the elevation probably reflecting tachycardia rather than myocardial infarction.

The patient did maintain oxygen saturations at 96% on air, and his FVC stabilised, but persisting tachycardia and tachypnoea (respiratory rate 24/minute) prompted a request for a CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) to exclude pulmonary embolism. Unfortunately, he rapidly developed a combination of falling oxygen saturations (to 88% on room air) and increasing dependence on oxygen, drowsiness and the development of fast atrial fibrillation. This prompted admission to the intensive care unit, where he required ventilatory support. He became too unwell to tolerate a CTPA. Chest X-rays suggested right basal consolidation in keeping with suspected aspiration of NG feed. At this point, given the presence of several comorbidities, a poor prognosis was communicated to the patient's family. He was treated with iv gentamicin, meropenem, verapamil and amiodarone, and later also underwent tracheostomy.

Case progression

Further neurological examination was difficult given the patient's condition and the intensive care unit setting, but he was found to have become areflexic, with bilateral facial weakness. Given the nature of his deterioration and the additional possibility of autonomic instability (tachycardia), it was important to exclude GBS. EMG and nerve conduction studies (5 days after symptom onset) were also very challenging. Repetitive nerve stimulation did not show a consistent decrement, so findings were insufficient to be diagnostic of MG. There was no supportive evidence of GBS. Active neuropathic changes involving right-sided L4, L5, S1 and S2 innervated muscles were suggested to be the result of a proximal cause, such as acute lumbosacral radiculopathy. The patient did undergo a lumbar puncture, which showed elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein (1.24 g/l) but otherwise normal constituents. On clinical grounds, the prominent fatiguability favoured MG, but the finding of CSF cytoalbuminological dissociation clearly raised the possibility of GBS.

The patient received treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (total dose 140 g over 5 days) and did show gradual improvement. Acetylcholine receptor antibodies were found to be strongly positive (59.5 nmol/l). Anti-glycolipid antibodies were negative. A repeat neurophysiological examination (17 days after symptom onset) revealed peripheral sensory studies to be within acceptable limits of normal in the upper and lower limbs. Repetitive nerve stimulation showed significant decrement (10 to 17%) on stimulation of the right median nerve and right facial nerve, supporting generalised MG. Again, supportive evidence was provided for lumbosacral radiculopathy. An MRI lumbosacral spine showed diffuse degenerative changes but only mild L4/L5 level canal stenosis.

Currently, 20 months after initial presentation, the patient remains under outpatient follow-up and is continuing a favourable clinical course on mycophenolate mofetil and pyridostigmine.

Discussion

The prevalence of MG has recently been estimated to be 131–145 per million population, with incidence rates of 6.7 per million in those younger than 50 years and 34 per million in those older than 50 years of age.1 The diagnosis of MG rests on clinical and paraclinical findings, specifically symptoms, effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, EMG, and the presence of autoantibodies or thymoma. The diagnostic and clinical classification has been expertly discussed very recently.2

Although MG is an uncommon disorder, it is increasingly encountered in an ageing population. In the acute medicine setting, a range of acute-onset neurological symptoms are not infrequently initially attributed to stroke. It is crucial, therefore, to have an awareness of the diversity of conditions that can cause apparently acute or subacute neurological dysfunction. Purely anecdotally, as a neurologist attending a stroke unit that serves a population of approximate 380,000 people, one of the authors (HE) has encountered new-onset MG presenting to the stroke unit approximately once a year.

There were a number of complexities in this case, not least the difficulty posed by the patient's rapid deterioration in respect of establishing the diagnosis as swiftly as possible. With regard to confirming the clinical suspicion of MG, EMG is difficult to undertake and interpret in the setting of an acutely unwell patient; acetylcholine receptor antibody testing is generally subject to delay resulting from the batching of samples by clinical laboratories; and the utility and safety of a tensilon test is questionable in an elderly patient who has a degree of haemodynamic instability. The elevated CSF protein was a confounding factor but was probably attributable to a combination of lumbosacral spine disease3 and cerebral small vessel disease that brought about loss of blood–brain barrier integrity.4 An alternative possibility, the co-occurrence of MG and GBS (which has been described5), was considered to be an extremely unlikely explanation for the elevated CSF protein. GBS was not supported by the neurophysiological findings in our patient, whereas significant decrement, sufficient to meet diagnostic criteria for MG, was observed on repetitive nerve stimulation.

Conclusion

This case reaffirms the value of prompt, accurate, neurological assessment and adherence to the clinical diagnostic formulation. This is especially important in the acute setting where the interpretation of investigation findings is not straightforward.

References

- 1.Andersen JB, Heldal AT, Engeland A, Gilhus NE. Myasthenia gravis -epidemiology in a national cohort; combining multiple disease -registries. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2014;129(Suppl 198):26–31. 10.1111/ane.12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berrih-Aknin S, Frenkian-Cuvelier M, Eymard B. Diagnostic and clinical classification of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun 2014;48–49:143–8. 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seyfert S, Kunzmann V, Schwertfeger N, Koch HC, Faulstich A. Determinants of lumbar CSF protein concentration. J Neurol 2002;249:1021–6. 10.1007/s00415-002-0777-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrall AJ, Wardlaw JM. Blood-brain barrier: ageing and microvascular disease – systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:337–52. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Niu S, Wang Y, Hu W. Myasthenia gravis and Guillain-Barré cooccurrence syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:1264–7. 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]