ABSTRACT

Falls in later life are a major health issue, both in terms of their injurious consequences and their significance as a diagnostic marker. Cost-effective measures for their assessment and prevention are well documented but insufficiently implemented. This Concise Guideline comprises a distillation of recommendations for the assessment and prevention of falls in older people based on Clinical Guideline 161 (incorporating CG21) published by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2013. The recommendations are intended to provide both generalists and specialists with an overview of practical strategies for clinical case and/or risk ascertainment and intervention, and for referral and service implementation across the primary–secondary care interface and within the hospital setting. Recommendations abstracted verbatim from the Guideline are highlighted. Explanatory or supporting comment is given as appropriate.

KEYWORDS: Falls, risk assessment, diagnosis, intervention, prevention

Introduction

The phenomenon of falls affecting older people is a widely misunderstood clinical entity of major public health importance. It is a classic age-associated syndrome reflecting two things: (1) diminution in the functional reserve capacity of certain afferent, central and efferent mechanisms involved in maintaining the upright position (orthostasis); and (2) the consequent vulnerability of those mechanisms to associated accident, impairment, active disease process, adverse pharmacological stimulus or any combination of these. People aged 65 or older have the highest risk of falling, with 30% of people older than 65 and 50% of people older than 80 falling at least once a year. Without intervention in those susceptible, the costs and consequences to individuals, their families and carers, and to healthcare are substantial, including distress, pain, injury, loss of confidence, loss of independence, mortality, and an estimated annual NHS outlay exceeding £2.3 billion.1

Two superficially counterintuitive, but essential and parallel, concepts of the phenomenon require understanding and are highlighted by the evidence: the first is that substantial prevention is achievable among those presenting to health services and found to be at risk, whereas the second is that the diagnostic yield of early and/or previously undetected treatable health problems in those susceptible to falls is considerable, but can be elusive.

Although evidence for cost-effectiveness based on averting the direct consequences of falls (notably injury) is compelling, the more indirect health dividends of timely disease detection and treatment are likely to be substantial, as indicated, for example, by reported achieved reductions in hospital admission and length of stay.

A National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline was published in 2004 (CG21)2 subsequent to recommendations by the England National Service Framework for Older People (2001).3 CG21 included all older (>65 years of age) people presenting to healthcare professionals in the NHS (whether or not admitted to hospital), but excluded (for lack of evidence) explicit guidance on measures to prevent falls during a hospital stay. CG161 (June 2013)1 incorporates CG21 (minor stylistic changes only), based on the conclusion that ‘all its recommendations remain as relevant and important as when originally published’,1 together with new evidence and guidance covering the hospital (inpatient) stay.

Since the publication of CG21 (2004), national audits have shown unacceptably low levels of implementation.4 Therefore, there is an urgent need to rectify this.

Although research endeavour and output in the topic to date reflect predominantly the interests and expertise of primary and secondary care clinicians with a defined focus on ageing and older people, the phenomenon is inevitably and increasingly encountered by all clinicians dealing with adults. CG161 sets out broad evidence-based guidance to enable effective management across the spectrum of clinical practice. It should be linked to consideration of related guidance, including in particular Hip Fracture (CG124)5 and Osteoporosis and Fragility Fracture Risk (CG146).6

Scope and purpose

The CG161 guidance (and supporting evidence) relates to risk detection and prevention among older people in the specific context of NHS ‘encounter’. (There is a wider debate and a separate body of evidence concerning strategies for the promotion of optimal physical fitness (and, hence, falls prevention) at the population level, including the wider low-risk general population of ‘fit’ older people (most notably by means of single-intervention tailored exercise programmes)7,8).

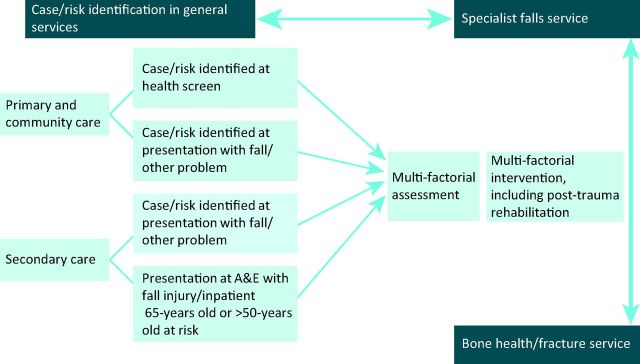

This Concise Guideline is limited to the scope of CG161. It abstracts and highlights the key points of the guidance for the generalist and specialist, and derives strategies aimed at ensuring effective cross-linkage (Fig 1) and overcoming barriers to implementation. Recommendations abstracted verbatim from the NICE Guideline are bullet-pointed. Others are referred to in the text to avoid repetition and retain clarity. As in CG161, this concise presentation will first address the CG21 component covering all people over the age of 65, and then the more recent guidance concerning hospital stays.

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of falls assessment and prevention pathway, modified from NICE clinical practice guideline.2 A&E = accident and Emergency; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

The recommendations

Case and/or risk ascertainment

Randomised controlled studies in the relevant category reporting effective falls prevention (ranging between 30% and 55% reduction versus control over 12 months) have incorporated a distinct risk identification strategy, which emerges as an absolute requirement. Earlier positive USA trials have used prospective structured community-based screening.9 UK-based positive trials have adopted a less costly, more opportunistic approach to risk identification by selecting anticipated high-risk groups, such as consecutive emergency department attendees or ambulance call-outs.10–12 The indicators of risk observed within these population samples, in particular a past history of falls and the presence of balance and gait abnormalities, have underpinned the rationale for an opportunistic approach to risk detection in the NHS.

Older people in contact with healthcare professionals should be asked routinely whether they have fallen in the past year and asked about the frequency, context and characteristics of the fall/s.

Older people reporting a fall or considered at risk of falling should be observed for balance and gait deficits and considered for their ability to benefit from interventions to improve strength and balance.

The need to specify such an approach reflects a relative historical deficiency of awareness, and corresponding omission of such routine enquiry and observation from ‘standard’ diagnostic case-history taking and clinical examination. Demographic change underpins this necessary update.

In recommending a basic refinement of normal clinical procedure to promote opportunistic risk detection (as distinct from population screening), CG161 guidance draws on the evidence, adopts a pragmatic approach to NHS practice, and requires a minimal additional commitment of time on the part of the generalist.

Multifactorial assessment

The Guideline predicates detailed individualised assessment (by clinicians with a specific and accountable focus of expertise in the field) of those ascertained to be at risk, in general by onward referral to a defined service.

Older people who present for medical attention because of a fall, or report recurrent falls in the past year, or demonstrate abnormalities of gait and/or balance should be offered a multifactorial falls risk assessment. This assessment should be performed by a healthcare professional with appropriate skills and experience, normally in the setting of a specialist falls service. This assessment should be part of an individualised, multifactorial intervention.

Although in a proportion of those at risk a single definitive cause (eg cardioinhibitory carotid sinus syndrome)13 might be determined, in most patients, multiple contributory factors are identified. The guidance identifies a range of intrinsic and extrinsic factors (not exhaustive or exclusive) commonly emerging from the evidence and highlighting the importance of multidisciplinary input. Against a backdrop of careful and focused clinical diagnosis, the itemised range includes:

identification of falls history

- assessment of:

- gait, balance, mobility, and muscle weakness

- osteoporosis risk

- the older person's perceived functional ability and fear relating to falling

- visual impairment

- cognitive impairment and neurological examination

- urinary incontinence

- home hazards

- cardiovascular examination and medication review.

Generalists might wish to initiate elements of this process. The precise service configuration can be anticipated to vary across centres, but defined accountability and clinical governance are ultimately implicit, and a strategy for coordination and/or localisation is integral to implementation, ensuring that all necessary elements of multifactorial assessment and intervention for any individual can be coordinated via a unified referral track. (See implications for implementation, below).

Multifactorial intervention

Where a clear diagnostic entity is identified by a clinician (generalist or specialist), the logical progression to management is self-evident, whether it be pacemaker insertion for cardiogenic syncope13 or (to cite an unusual, but actual example) successful hemicolectomy for a caecal carcinoma-related paraneoplastic syndrome with lower limb peripheral neuropathy. (Such instances highlight the sometimes-elusive nature of the diagnosis. The ubiquitous ‘UTI’ based on a single positive urine sample is a frequent and notorious alibi).

In addition, several elements of intervention have been sufficiently common in positive trials to merit specific mention in the guidance.

All older people with recurrent falls or assessed as being at increased risk of falling should be considered for an individualised multifactorial intervention.

- In successful multifactorial intervention programmes, the following specific components are common (against a background of the general diagnosis and management of causes and recognised risk factors):

- strength and balance training

- home hazard assessment and intervention

- vision assessment and referral

- medication review with modification/withdrawal.

Again, generalists might wish to initiate elements of this process. Access to coordinated multidisciplinary practice – including physiotherapy and occupational therapy – as well as to full diagnostic investigational facilities is required for the effective delivery of the recommendation, which, importantly, is explicitly inclusive of older people in extended care settings.

There is further emphasis in the guidance on strength and balance training, reflecting its prevalence within the evidence for successful multifactorial interventions, with particular emphasis on those with a history of recurrent falls and/or balance and gait deficit. Impairment is commonly both a consequence and a cause of falls events or susceptibility. Prescription and monitoring by an appropriately trained physiotherapist are essential.

The necessity for home hazard assessment by an appropriately trained healthcare professional is further emphasised as part of discharge planning after hospitalisation resulting from a fall. Psychotropic medication is also highlighted for scrutiny as part of medication review.

However, none of the above bullet-pointed components are supported for implementation in isolation from an overarching, individualised multifactorial intervention.

The importance of awareness of cardiovascular syncope and related phenomena (involving history, examination and clinical measurement) is further highlighted:

cardiac pacing should be considered for older people with cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity who have experienced unexplained falls.

Not recommended

Several specific interventions for which evidence of efficacy as single interventions was insufficiently robust are singled out for avoidance: low intensity exercise combined with incontinence programmes; untargeted group exercise; cognitive/behavioural interventions; correction of visual impairment; vitamin D; and hip protectors.

Prevention during a hospital stay

Since the publication of CG21, there now exists a sufficient body of evidence to support recommendations applicable to a hospital stay.

Case and/or risk identification

Prediction tools designed to ascertain risk in the hospital setting have not so far proved either robust or reliable.14 As expected, given the prevalence of comorbidity in this context, older patients in general in hospital are at particularly high risk. Accordingly, a baseline assumption is considered appropriate in all those over 65 years of age. In certain circumstances, some younger patients (over 50 years of age) have also been included in studies of successful intervention.

Do not use fall risk prediction tools to predict inpatients’ risk of falling in hospital.

- Regard the following groups of inpatients as being at risk of falling in hospital and manage their care according to recommendations (below):

- all patients aged 65 years or older

- patients aged 50–64 years who are judged by a clinician to be at higher risk of falling because of an underlying condition.

Multifactorial assessment and intervention

In essence, the individualised diagnostic and interventional approach for those at risk during hospital inpatient stays follows the principles and rationale outlined for the broader group above (covering intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors), and there is now modest evidence (reflected in the 2013 use of the term ‘consider’) for its efficacy.15,16 By definition, localisation of diagnostic facilities and professional disciplines is inherent in the hospital setting.

For patients at risk of falling in hospital, consider a multifactorial assessment and a multifactorial intervention.

Ensure that any multifactorial assessment identifies the patient's individual risk factors for falling in hospital that can be treated, improved or managed during their expected stay.

Ensure that any multifactorial intervention promptly addresses the patient's identified individual risk factors for falling in hospital and takes into account whether the risk factors can be treated, improved or managed during the patient's expected stay.

Do not offer falls prevention interventions that are not tailored to address the patient's individual risk factors for falling.

A range of component factors derived specifically from inpatient studies (not exhaustive, and almost identical to those previously listed above) is itemised, including:

cognitive impairment

continence problems

falls history (including causes and consequences (such as injury and fear of falling))

footwear that is unsuitable or missing

health problems that may increase risk of falling

medication

postural instability

mobility problems and/or balance problems

syncope syndrome

visual impairment.

Adoption of these measures for hospital stays is demonstrably cost-effective, although there might be variation between different inpatient settings.

Limitations of the Guideline

Methods for determining the quality of evidence and for health economics are non-uniform across the Guideline, given that full formal review of CG21 was not considered necessary or undertaken as part of CG161. Evidence to support the efficacy of the recommendations in older people with cognitive impairment is lacking,17 although this group was not excluded in several studies.

As with all NICE guidelines, the evidence for some individual recommendations is stronger than for others. Other than the existence of a ‘specialist falls service’, the guidance is not prescriptive for lines of accountability or service configuration.

Implications for implementation

As already stated, notwithstanding the strength of the evidence, the track record of implementation to date has been poor.4 Contrary to expectation, the overwhelming flood of anticipated referrals to ‘specialist falls services’ has simply not materialised. The potential individual and health economic return for cost-effective intervention is not being realised, for example the reductions in annual hospital admission rates (27%)10 or hospital bed days (81%)11 achieved in some studies. Therefore, urgent but practical steps are needed to rectify this.

Advice to patients

To improve implementation, skill and sensitivity in communicating the concept in advice to patients will be needed, alongside the mind-set shift within routine clinical practice inherent in the guideline. Insensitive discussion of falls risk among older people has commonly induced a subtle sense of stigmatisation in some, resulting in a reluctance to accept intervention.

Clinical practice and referral

The guidance identifies several generic elements of clinical practice and service provision as follows.

Case and/or risk ascertainment

The process of case and/or risk ascertainment as described is neither complex nor time-consuming for the generalist and now requires integration into standard clinical practice in both primary and secondary care. However, to motivate and enhance awareness, a clear and easily accessible response and referral track (see below) is needed across the primary–secondary care interface and within hospital practice. Inclusion in the Quality Outcomes Framework (including the possibility of an Enhanced Service) could provide incentive. (Based on the evidence, those over 65 years of age attended by the ambulance service at home after a fall, those presenting to emergency departments, and all inpatients over 65 years of age could be considered at risk till proven otherwise.10,12,15)

Multifactorial assessment and intervention

Initiation and follow-through of the key components of multifactorial assessment and intervention for those at risk, as well as the acceptance of inpatient or outpatient referrals for this purpose, should be integral to the specialist practice of all clinicians in primary or secondary care with defined expertise in clinical gerontology, preferably following standard protocols. Many generalists might themselves wish to initiate or authorise some or all of these components, but the Guideline stipulates a systematic approach addressing, as a minimum, the risk factors itemised and following these through: therefore, ready access to all relevant diagnostic investigation, multidisciplinary collaboration and follow-up is needed.18,19 This might well necessitate referral. For hospital inpatients, a protocol-driven process is commonly initiated by ward nursing staff.15

Specialised falls assessment and management clinics

Defined specialised falls assessment and management clinics incorporating more sophisticated clinical measurement capability, such as detailed physiological profiling20 and tilt-table testing, might possibly focus more selectively on referrals of those presenting with more complex problems or suspected cardiogenic syncope.

Clinical governance and coordination

To achieve the required leadership, clinical governance, accountability and coordination, the following appear necessary and have commonly been implemented in centres delivering effective services: (1) A single clinician with the required expertise providing medical (including diagnostic) accountability for the service in collaboration with medical and multidisciplinary colleagues; and (2) A falls service coordinator (usually a specialist nurse or therapist) providing leadership in ward-based management for inpatients and a first point of referral; also maintaining a register and tracking the progress of those at risk, both within hospital and across the primary–secondary care interface, including liaison with the ambulance service.

A NICE Quality Standard and Commissioning Guide are scheduled for development.

Acknowledgements

A full list of Guideline Development Group members can be found on the NICE website for CG161.1 CGS and SI are both GDG members.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Falls: Assessment and prevention of falls in older people. NICE Clinical Guideline 161. London: NICE, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Clinical practice guideline for the assessment and prevention of falls in older people. London: NICE, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health National service framework for older people. London: DH, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal College of Physicians Falling standards, broken promises. Report of the national audit of falls and bone health in older people. London: RCP, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Hip fracture: the management of hip fracture in adults. NICE Clinical Guideline 124. London: NICE, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture. NICE Clinical Guideline 146. London: NICE, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherrington C, Whitney JC, Lord SR, et al. Effective exercise for the prevention of falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:2234–43. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iliffe S, Kendrick D, Morris R, et al. Multicentre cluster randomised trial comparing a community group exercise programme and home-based exercise with usual care for people aged 65 years and over in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2014;18:1–106. 10.3310/hta18520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinetti ME, Doucette J, Claus E, Marottoli R. Risk factors for serious injury during falls by older persons in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:1214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, et al. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1999;353:93–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davison J, Bond J, Dawson P, Steen IN, Kenny RA. Patients with recurrent falls attending accident & emergency benefit from multifactorial intervention – a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2005;34:162–8. 10.1093/ageing/afi053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logan PA, Coupland CA, Gladman JR, et al. Community falls prevention for people who call an emergency ambulance after a fall: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c2102.c2102. 10.1136/bmj.c2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenny RA, Richardson DA, Steen N, et al. Carotid sinus syndrome: a modifiable risk factor for non-accidental falls in older adults (SAFE PACE). J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1491–6. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01537-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver D. Falls risk-prediction tools for hospital inpatients. Time to put them to bed? Age Ageing 2008;37:248–50. 10.1093/ageing/afn088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healey F, Monro A, Cockram A, Adams V, Heseltine D. Using -targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in-patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2004;33:390–5. 10.1093/ageing/afh130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cumming RG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a targeted multifactorial intervention to prevent falls among older people in hospital. BMJ 2008;336:758–60. 10.1136/bmj.39499.546030.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw FE, Bond J, Richardson DA, et al. Multifactorial intervention after a fall in older people with cognitive impairment and dementia presenting to the accident and emergency department: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003;326:73–5. 10.1136/bmj.326.7380.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lightbody E, Watkins C, Leathley M, Sharma A, Lye M. Evaluation of a nurse-led falls prevention programme versus usual care: a randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing 2002;31:203–10. 10.1093/ageing/31.3.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spice CL, Morotti W, George S, et al. The Winchester falls project: a randomised controlled trial of secondary prevention of falls in older people. Age Ageing 2009;38:33–40. 10.1093/ageing/afn192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lord SR, Menz HB, Tiedemann A. A physiological profile approach to falls risk assessment and prevention. Phys Ther 2003; 83:237–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]