ABSTRACT

Diabetes is an increasingly common health problem, and accounts for one-tenth of NHS spending, chiefly managing avoidable complications. Approximately one-third of people with diabetes have psychological and/or social problems which impede their ability to self-manage their diabetes. Identifying certain indicators which suggest high risk of co-morbid mental health problems will allow these to be identified and treated early. Ensuring that any mental health problems are treated and social needs are met, will be valuable in improving the individuals health. Addressing the psychiatric and psychological barriers to good glucose control can help to reduce the burden of diabetes and its complications, on both the individual and the wider health service.

KEYWORDS: Diabetes mellitus, psychiatry, behavioural medicine, anxiety, depression

Key points

Psychiatric and psychological comorbidities are common in diabetes

These comorbidities are associated with poorer outcomes

Psychological treatments improve outcomes

There is a growing evidence base for integrated care

Introduction

Diabetes is an increasingly common health problem, especially in the West, where there is an emerging epidemic of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes accounts for one-tenth of NHS spending, and 80% of this is spent on managing potentially avoidable complications.

Many people who have diabetes struggle to optimise their diabetes control, often because of comorbid mental illness or psychological and social problems. Unfortunately, poor diabetes control has significant consequences for the individual, and if not addressed, will result in the development of complications that include blindness, kidney failure and even amputations. In addition to the consequences for the individual, these complications have an impact on health services in the form of increased admissions, out-patient attendances and emergency department presentations with diabetes-related difficulties. In the long-term, the costs associated with complications resulting from uncontrolled diabetes, such as renal failure and amputation, are very high. Approximately one-third of people with diabetes have psychological and/or social problems that impede their ability to self-manage their diabetes.1

Epidemiology

The evidence base for the interrelationship of diabetes with mental illness has increased over the past 13 years. In 2001, Anderson et al2 conducted a meta-analysis which indicated that the presence of diabetes doubled the risk of comorbid depression. A systematic review of more recent literature, published in 2012 by Roy and Lloyd,3 found rates of depression in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes three times and twice those in the general population, respectively. An understanding of the bi-directional pathophysiological relationship between diabetes and depression has been elucidated by Rustad et al,4 but key posited aetiologies are activation of the innate immune system and increased activity of the hypothalamic – pituitary – axis, in addition to the psychological burden of the illness. The significance of a double diagnosis of diabetes with depression is illustrated by the associations with non-adherence to treatment, poor glycaemic control and increased numbers of complications (including diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, macrovascular problems and sexual dysfunction).5–7 In addition, Park et al8 found a hazard ratio of 1.5 (1.35–1.66) for all-cause mortality in depressed patients with diabetes.

Eating disorders are also associated with diabetes. In a meta-analysis published in 2005, Mannucci et al9 found that bulimia nervosa is more prevalent in females with type 1 diabetes in comparison to the normal (ie non type 1) female population (1.73 vs 0.69). Evidence for eating disorders in type 2 diabetes is less established, although this form of diabetes is associated with an increased prevalence of binge eating disorder.10,11 Although anorexia nervosa is not at increased prevalence in the diabetes population, patients with either anorexia or bulimia nervosa are significantly at risk of complications (retinopathy and nephropathy) and mortality if using insulin omission as a method of weight loss.12,13

In a meta-analysis by Smith et al in 2012, the odds ratio (OR) for anxiety disorder was 1.20 (1.10–1.31) and for anxiety symptoms 1.48 (1.02–1.93), whereas the pooled OR was 1.25 (1.10–1.39).14 Anxiety disorders diagnosed by diagnostic interview have also been shown to be significantly associated with poor glycaemic control.15

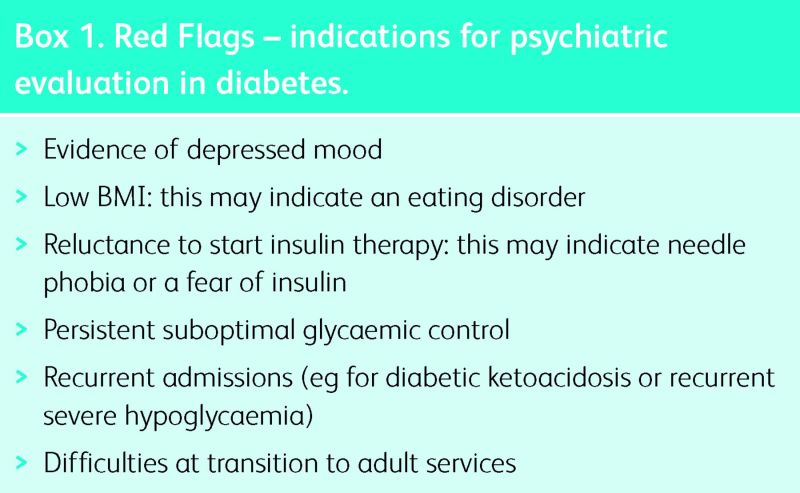

Specific psychological problems in diabetes

In addition to these relationships with mental illness, diabetes is associated with specific psychological problems that may have a direct effect on glycaemic control, and thus on the development of complications, future physical disability and mortality. Box 1 shows a number of indications for psychiatric assessment in diabetes.

Box 1. Red Flags – indications for psychiatric evaluation in diabetes.

Acceptance of diagnosis, denial and uncertainty

Individuals who have received a recent diagnosis of diabetes frequently describe difficulties in adjusting to the diagnosis. In particular, they may report difficulties around acceptance of the diagnosis of a long-term condition that requires constant self-management if the long-term sequelae are to be avoided. This can involve a variety of responses from a depressive or grief-type reaction to denial and avoidance, all of which can result in poor glycaemic control.

Fear of hypoglycaemia

The subjectively unpleasant experience of hypoglycaemia might result in the individual being so anxious to avoid its recurrence that they run their blood glucose much higher than recommended (often particularly at night), and as a result glycaemic control deteriorates.

Fear of complications

Most patients take information regarding potential complications in their stride, but there are a small number of individuals who become fearful of developing these conditions. When some individuals see a high glucose reading (despite his/her best efforts), she/he feels that no matter what steps she/he takes, she/he cannot fully control his/her diabetes and immediately infers that this means that complications are inevitable. This results in the person feeling discouraged about their diabetes control and perhaps avoiding of the necessary self-care behaviours (to avoid these feelings of failure), which may paradoxically increase the risk of developing diabetes complications.

Adherence

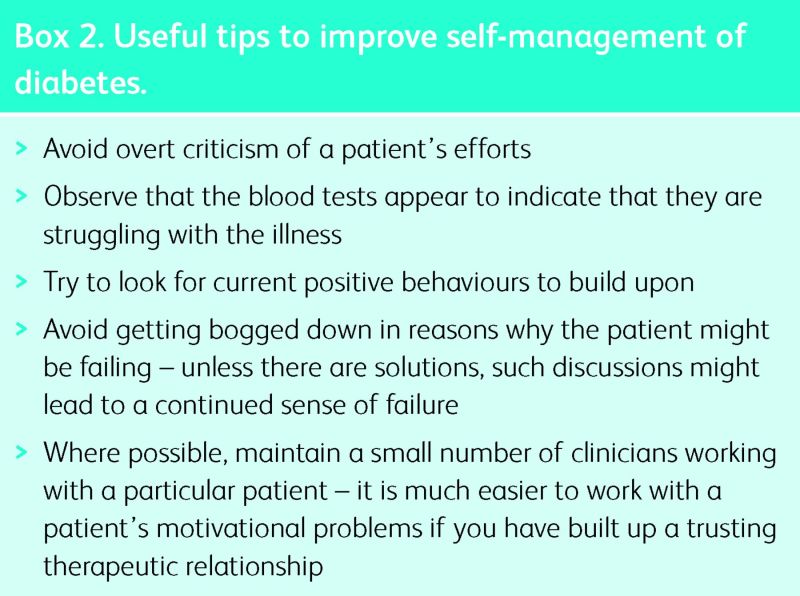

Many patients find it difficult to adhere to the full self-care regimen required for optimal diabetes control. This may be for any of a wide range of reasons, including mental illness or social problems that absorb the individual's attention. The demands of self-management are large and can be difficult to incorporate into a busy lifestyle. In order for these important activities to occur, they must be prioritised as important by the individual. Most people who have diabetes know what they need to do in order to manage their diabetes better, but the challenges of daily life get in the way. A ‘motivational interviewing’ approach can be useful in helping patients to overcome the barriers to good self-care behaviours, and to prioritise appropriately. These techniques can be usefully incorporated into any consultation (Box 2).

Box 2. Useful tips to improve self-management of diabetes.

Management

The management of axis I mental disorders in diabetes is not dissimilar to the management of these conditions in the general population. Nevertheless, when the effect of diabetes on a patient's mental status is considered alongside their mental disorder, it is more likely that the individual's physical and mental health will improve. The effect of the mental disorder on the individual's physical health means that psychological interventions are indicated at a lower symptom threshold than would be used for people who do not have diabetes.16,17

Antidepressants are frequently required in the treatment of depression in diabetes. Certain antidepressants, notably duloxetine, amitryptilline and nortryptilline, are licensed for the treatment of pain resulting from diabetic neuropathy, and are useful choices for patients who have comorbid depression and neuropathic pain. Likewise, pregabalin is licensed for the treatment of neuropathic pain, and could be considered for comorbid neuropathy and anxiety. It had been postulated that antidepressants might have a direct action in reducing insulin resistance, although this has been refuted.18

There is robust evidence to support psychological interventions, such as motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), for the management of psychological problems in diabetes. In addition to improving psychological well-being, psychological interventions have been shown to significantly improve glycaemic control in patients, with a mean reduction in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of 0.5% associated with 12 sessions of a face-to-face programme involving motivational interviewing plus CBT.19 A recent randomised controlled trial of adherence-focused CBT has demonstrated similar improvements.20

Models of care

Various innovative models of integrated care have evolved in recent years, demonstrating that the integration of psychiatry and diabetes care can result in improvements, not only in mental health, but also in physical health status. In the USA, the Team Care model, which entailed enhanced diabetes care for people with diabetes and depression, with psychological therapies delivered by diabetes nurses under the supervision of a psychiatrist, demonstrated improvements in glycaemic control.16 Likewise, the London-based 3 Dimensions of Care For Diabetes service, which addresses the social and psychological dimensions of living with diabetes by integrating medical, psychological and social care for patients with persistent poor glycaemic control, has produced outcomes that demonstrate improved glycaemic control, improved psychological well-being, improved patient satisfaction and reduced use of unscheduled care and related costs.17

Improving outcomes

Diabetes is a common problem that frequently overlaps with mental illness. Clinician awareness of the person's mental health and supporting them to improve their mental health and coping strategies may reduce their risk of developing the complications of diabetes. Identifying certain ‘red flags’ that suggest high risk of comorbid mental health problems will allow these patients to be identified and treated early (Box 1).

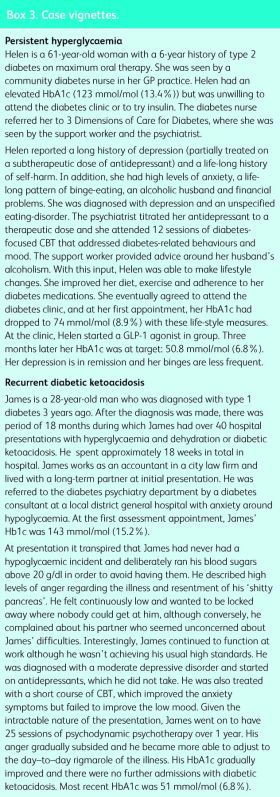

The two case vignettes described in Box 3 indicate the importance of including a psychiatric approach, or at least of considering the psychological process that might be at play, in a given clinical situation. Some patients will require specialized psychiatric or psychological input. For others, incorporating basic psychological techniques into your consultation may be useful in overcoming resistance to change and barriers to ideal adherence (Box 2).

Box 3. Case vignettes.

Most crucially, treating the person's mental health problems and ensuring that, where present, any social needs are met, will be useful in improving the individuals health.

Addressing the psychiatric and psychological barriers to good glucose control can help to reduce the burden of diabetes and its complications, on both the individual and the wider health service.

References

- 1.Grigsby AB, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:1053–60. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00417-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1069–78. 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy T, Lloyd CE. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: a -systematic review. J Affect Disord 2012;142 Suppl:S8–21. 10.1016/S0165-0327(12)70004-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rustad JK, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression and diabetes: pathophysiological and treatment -implications. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011;36:1276–86. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2008;31:2398–403. 10.2337/dc08-1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 2000;23:934–42. 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta–analysis. Psychosom Med 2001;63:619–30. 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park M, Katon WJ, Wolf FM. Depression and risk of mortality in individuals with diabetes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:217–25. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannucci E, Rotella F, Ricca V, Moretti S, Placidi GF, Rotella CM. Eating disorders in patients with type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Endocrinol Invest 2005;28:417–9. 10.1007/BF03347221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorin AA, Niemeier HM, Hogan P, et al. Binge eating and weight loss outcomes in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:1447–55. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mannucci E, Tesi F, Ricca V, et al. Eating behavior in obese patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:848–53. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takii M, Uchigata Y, Tokunaga S, et al. The duration of severe insulin omission is the factor most closely associated with the microvascular complications of Type 1 diabetic females with -clinical eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2008;41:259–64. 10.1002/eat.20498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goebel-Fabbri AE, Fikkan J, Franko DL, Pearson K, Anderson BJ, Weinger K. Insulin restriction and associated morbidity and mortality in women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008;31:415–9. 10.2337/dc07-2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith KJ, Béland M, Clyde M, et al. Association of diabetes with anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2013;74:89–99. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson RJ, Grigsby AB, Freedland KE, et al. Anxiety and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med 2002;32:235–47. 10.2190/KLGD-4H8D-4RYL-TWQ8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGregor M, Lin EH, Katon WJ. TEAMcare: an integrated multicondition collaborative care program for chronic illnesses and depression. J Ambul Care Manage 2011;34:152–62. 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31820ef6a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archer N, Ismail K, Bridgen O, Morgan Jones R, Price L, Gayle C. Three Dimensions of Care for Diabetes: a pilot service. J Diabetes Nurs 2012;16:3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pyykkonen AJ, Raikkonen K, Tuomi T, Eriksson JG, Groop L, Isomaa B. Depressive symptoms, antidepressant medication use, and insulin resistance: the PPP-Botnia Study. Diabetes Care 2011;34:2545–7. 10.2337/dc11-0107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ismail K, Maissi E, Thomas S, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy and motivational interviewing for people with Type 1 diabetes mellitus with persistent sub-optimal glycaemic control: a Diabetes and Psychological Therapies (ADaPT) study. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:1–101, iii-iv 10.3310/hta14220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Wexler DJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:625–33. 10.2337/dc13-0816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]