Abstract

The UK has recognised the important role its health professionals play in achieving the Millennium Development Goals. For doctors to contribute to these efforts without detracting from domestic service and training commitments presents a challenge. Moreover, doctors need suitable education in order to make appropriate and effective contributions in resource-poor settings. In this article it is argued that, while mechanisms exist within current UK postgraduate training that permit a degree of flexibility to training pathways, they are not structured in a way that facilitates work in low and middle income countries. Furthermore, the knowledge and skills required to make contributions to global health are not sufficiently served by existing training. A model for a national curriculum and tiered qualifications in global health is proposed, based on rigorous appraisal and mentoring to complement the training pathways for UK specialisation, allowing doctors to add global health skills at a level appropriate for their career plans.

Key Words: education, global health, postgraduate, training

Global health training and work in resource-poor countries

Global health is a broad field incorporating a variety of different ways of analysing world health and health inequality, including economic, social and political perspectives. Government, educationalists, non-governmental organisations and doctors agree that individual doctors, the NHS and its overseas counterparts have much to gain from UK clinicians' engagement in clinical work overseas and global health.1 This was codified with the Framework for NHS involvement in international development.2 Overseas work ranges from providing emergency humanitarian relief to adding manpower in stable settings where doctors are scarce. Benefits for the individual include experience of managing different medical conditions, of other healthcare systems, and of working in resource-poor settings.3 Doctors may also train local healthcare professionals and support them to improve health services. Links between UK and overseas healthcare institutions, such as those coordinated by the Tropical Health and Education Trust (THET), are increasingly important and are recognised as a key strategic aim in the government's global health policy.1 Doctors are also needed for global public health (UK or international, eg Department of Health (DH), World Health Organization (WHO), Global Fund) and to further UK global health research. The Alma Mata Global Health Graduates' Network, which links around 1,000 healthcare professionals with an interest in global health, found that over 95% of some 200 members surveyed aimed to return to work in the NHS.4 These doctors have a common desire to integrate work in, or with, resource-poor countries with their NHS career. As such, there is widespread recognition that doctors have a need for appropriate training and opportunities to engage with global health issues throughout their career.5

The benefits such overseas opportunities offer are far from guaranteed. Working effectively in starkly different contexts from the NHS requires fundamental practical and ethical concerns to be addressed. Such considerations will not be catered for within generic training structures unless specific global health needs are recognised. Incorporating such needs into a system already struggling with domestic training and service commitment requires flexibility and creative thinking. Health systems, whether in high, low or middle income countries, require professionals appropriately trained for the role they fulfil and a time commitment that allows effective planning of service provision. Trainees require educational opportunities and consideration for personal and family commitments, including job security.

Current flexibility

Since the advent of Modernising Medical Careers (MMC), changes to postgraduate training have the significant potential to improve the way the UK trains global health professionals. For the first time there is a defined structure from graduation onwards, with allowances for time out of programme (OOP) for experience (OOPE), research (OOPR), training (OOPT), or career break (OOPC). In addition to natural breaks in training this permits trainees a degree of personalisation. OOP brings the added advantages of job security on return. In spite of these provisions, many perceive the new system as having limited opportunities for doctors to work in resource-poor countries,6–8 and trainees feel that they must choose between a commitment to longer-term involvement with overseas work or specialty training.9 Many are uncertain how time off before applying for training will affect their career success; others within specialty training are uncertain of their rights in asking for OOP. Organisations like the British Medical Association (BMA), who published an overseas working guide,10 have begun to address this–more needs to be done to ensure that trainees and supervisors are aware of current allowances.

MMC has placed justifiable emphasis on educational supervision, assessment of competencies, and development of a portfolio of training. Previously the potential educational benefit of working overseas may have been under recognised; the application of similar educational rigour to overseas experience as exists for UK-based training has the potential to counter this. Such developments will need ways of overcoming specific difficulties faced in resource-poor settings, in particular, access to accredited supervisors or information technology, coupled with the possible lack of overseas experience of the trainee's educational supervisor or training programme director.

The London Deanery has recently made one structured placement available to several geneal practice (GP) trainees who work in rural South Africa for one year, with six months accredited for UK training. Two royal colleges (Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH)) have similar programmes where trainees work in a resource-poor country for one year with Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO). Accreditation is decided on a case-by-case basis. Accessible and structured programmes should be scaled up by interested colleges, institutions and non-governmental organisations. Existing opportunities within specialty training should be transparent and visible, and proposed time out should be accompanied by rigorous pre-departure preparation, and formal mentoring before and during time overseas, by a UK-based educational co-supervisor with relevant experience. Their additional role would be to assess the post for its compatibility with valid development and sustainability objectives. This requires the creation of a network of suitable mentors and educational co-supervisors in a range of clinical and academic specialisations. Such a network would require administrative support, which might be coordinated by one of the schools of tropical medicine or a royal college.11

A number of issues could be improved, however, within the current system of planning and approval of OOP. The Gold Guide states OOP can be taken to ‘help support the health needs of other countries’, but there are no explicit criteria to guide how applications are judged, allowing for different interpretations between and within deaneries. Time limits imposed on OOP may result in trainees making the difficult choice between compromising on training before going overseas, such as a postgraduate diploma or masters in a relevant discipline, and the length of time they are able to spend overseas. Provision for multiple OOP periods is uncertain, regardless of whether trainees are in uncoupled programmes, such as paediatrics with an eight-year run-through, or the three-year general practice. This leads to discrepancies in timing of the natural breaks which allow for further periods overseas, such as between foundation years, core training, and specialist training.

Many development agencies require applicants to have substantial work experience and transferable skills. There are, nevertheless, many situations in which, with appropriate supervision and mentoring, recently-qualified doctors can make valuable contributions. For those wishing to go overseas during natural breaks, the Gold Guide permits deferral only if accepted onto a higher degree though, in practice, some deaneries have allowed trainees to defer the start of training programmes. At best, this requires trainees to return to the UK for interviews, with subsequent financial implications and interruption of service overseas. At worst, it discourages trainees either from working overseas or from returning to the UK. The recent decision to allow applicants for GP training to sit their entrance exam one year in advance is supported,12 and it is hoped that granting of deferment for intended overseas service will become a rule rather than an exception.

Appropriate training

Previously, doctors working in resource-poor settings or, more generally, in global health, created their own unique career paths by taking ad hoc opportunities to train and work in relevant fields. If such a path were still possible, it is debatable whether it is desirable. There are concerns about students adopting roles beyond their competence during medical electives.13 As important are doctors working in new contexts without adequate preparation or competence; the development field is replete with well-meaning interventions causing harm due to unintended consequences and inadequate preparation.14 Standard UK postgraduate training does not give doctors the knowledge and skills to work effectively and appropriately in resource-poor environments. Moreover, if NHS institutional links with resource-poor countries are to grow, they require more doctors with appropriate training and experience to initiate, establish and successfully run such schemes.

Global health training

The subset of UK doctors planning to work in the resource-poor world need global health training in addition to their clinical training, whatever their specialty. Without recognising the determinant role of extreme poverty and health system constraints, doctors' contributions may be inappropriate or short lived. Such training would likely include topics on intercultural skills, health policy and development, health service planning and resource allocation, health systems strengthening, determinants of health, ethics in global health, and research methods. These skills, once developed, will remain relevant on return to the NHS, serving a multicultural society in which resource constraints and health inequalities feature large. Future senior doctors in charge of service delivery will be required to demonstrate that their model addresses the unmet needs of the communities they serve.

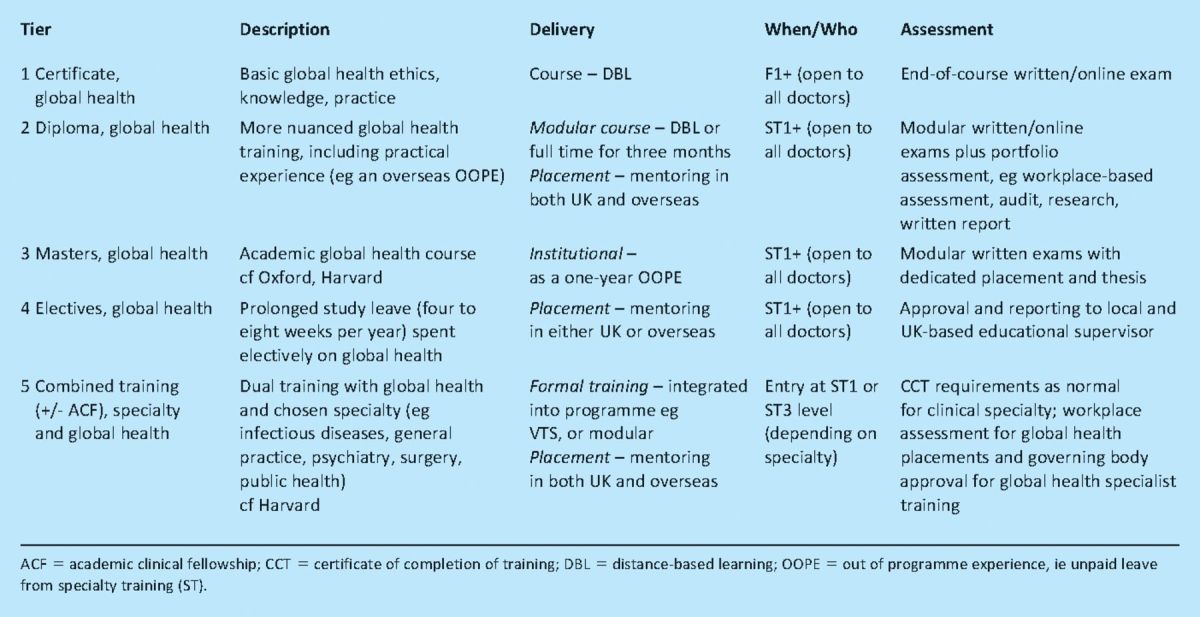

The past decade has seen an increasing number of medical students becoming active in global health, many through the student network Medsin.15 This interest has been catered for with a growing number of International Health Intercalated BScs, beginning with one run by the University College London (UCL) in 2001.16 Alma Mata proposes a model that allows work overseas, and global health more generally, to be effectively integrated with clinical training and career progression.17 Given the range of career intentions within our network, the level of training will vary with each doctor's path. Thus, the proposal centres on a nationally-recognised training structure, with a curriculum and tiered qualifications, so individuals can pursue appropriate training (Table 1). All qualifications would be in addition to the clinical specialty training of the doctor. These need to be equally appropriate to a career surgeon dealing in reconstructive surgery, to a psychiatrist helping post-conflict survivors, and to infectious diseases and public health clinicians dealing with societal-wide disease-control interventions. With the exception of the highest tier (combined training), the qualifications would be available to all, including staff and associate specialist doctors and those who have completed their certificate of completion of training (CCT). Trainees whose needs are not best served by our proposed system would, of course, not be prevented from following their own path.

Table 1.

A model of proposed UK postgraduate global health training structure.

Tiered qualifications and mentoring

The first tier consists of a certificate in global health, completed perhaps by distance-based learning, alongside clinical training. This would introduce the above concepts in broad detail, and might be suited to a doctor or health worker involved in an overseas link partnership. In contrast, a diploma in global health would include a period of study in the UK and a period overseas as OOPE, supervised and appraised by a suitably experienced and trained UK-based mentor acting as educational supervisor, similar to the existing scheme with RCPCH and VSO. The proposed diploma in global health would differ from, and complement, the more clinical emphasis of the existing diplomas in tropical medicine and hygiene (DTM&H), with more emphasis on health systems, policy, poverty and development, and less on specific diseases. The OOPE would be agreed in advance between the trainee and relevant deanery, with strict educational goals, during an attachment that satisfied criteria of sustainability, dictated by close consultation with the host country. These could be used to expand volunteering opportunities currently offered by royal colleges, such as psychiatry placements abroad with the Royal College of Psychiatrists.18 Higher tiers include existing masters courses and a global health elective scheme, whereby those developing a career in global health could apply to take extended study leave to pursue appropriate opportunities. All programmes would lead to accreditation in global health, recognised by an appropriate external body, and run alongside the usual progression to CCT in the individual's chosen specialty. A small minority would enrol in the highest tier of combined training, with a twin-track training programme providing concurrent schooling in global health and their clinical specialty.

Combined training models

Although several UK masters courses cover global health, at least in part, there has been no development of a professional track global health stream, as exists in the USA and elsewhere in Europe. Such programmes correspond to the highest tier of our model and target a small group of doctors who will spend their careers at a high level of practice, policy and research. The Global Health Education Consortium currently lists 12 global health residency programmes in North America.19 One example is the global health equity/internal medicine residency at Brigham and Women's Hospital at Harvard that combines ‘rigorous training in internal medicine with the advanced study of public health’.20 The four-year programme embeds teaching and training on the broader determinants of health and inequality into its clinical rotations, which are selected for their relevance to the promotion of equity and cultural competence, as well as allowing 11 months for field work and research. Residents leave the programme accredited in internal medicine with a masters in public health. Within the EU, examples include the Netherlands' tropical training organised by the Netherlands Society for Tropical Medicine and International Health.21 The residency consists of two years of clinical placements in hospitals with expertise in tropical training in the fields of surgery, obstetrics, gynaecology and paediatrics. During these attachments physicians attend training days on selected topics including dermatology, ophthalmology, HIV and tuberculosis, completing their training with a DTM&H. They are then expected to contribute substantively to healthcare overseas.

UK combined training

The training programme of this highest tier of the model would be tailored to those working within the NHS, affording the recipients of such training the skills required to drive the UK's contribution to the global health agenda. The structure could be a modular course that would run in addition to existing specialty training, extending the duration of this training by one or two years. The possible UK roles for doctors completing this combined training would include, but not be limited to:

developing and leading international institutional health links

ensuring integration and delivery of global health components in undergraduate and postgraduate training

mentoring and helping structure appropriate OOPE placements for UK doctors in training

leading the NHS's work to challenge health inequalities in the UK

fostering political will and developing funding streams for global health work within the NHS.

The future

The UK needs a nationally recognised system of training in global health that is embedded in existing specialty training programmes, yet flexible enough to cater for the heterogeneous needs of doctors wishing to contribute. Implementation of these recommendations will need widespread cooperation from the colleges and deaneries. Such an outcome will, in turn, need both a key organisation taking responsibility for designing and coordinating curriculum and its accreditation, and strong political commitment for global health and international development within and beyond the profession. A link organisation could be the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, which may be keen to take the leadership role forward. Key ownership from one college, such as the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology which has recently implemented various innovative pilot schemes for training overseas, will demonstrate achievable outcomes and provide stimulus for other royal colleges. Consistent junior doctor support from groups such as Alma Mata and the newly formed Intercollegiate Global Health Working Group to assist in development and implementation is clear, as is that from coordinators of international health BScs and MScs, and organisations such as THET and VSO. The upcoming Department for International Development-funded health partnership scheme could provide a vehicle for funding opportunities.22 What is also needed is engagement from senior clinicians, allied professions, and other academic staff involved with overseas links. With government support, such training could be streamlined with stepwise implementation over several years at a relatively small cost.

Dedicated training will foster enthusiasm for working in the resource-poor world and addressing global health problems, allowing doctors to gain skills that will maximise their contribution both in the UK and abroad. By integrating global health within mainstream training and practice, it is easy to envisage scenarios whereby a growing number of health professionals could spend some time working on global health activities, whether locally developing a link as part of a clinical attachment, hosting and teaching low and middle income country doctors, or introducing a global perspective to their hospital, college and professional teaching programmes. This could be incorporated into various assessments and statements of good practice, and could be established as a necessary recognised component of training. It would, for example, be relatively simple to build cultural or global competencies into doctors' online portfolios. Though individual's commitment will widely vary, creating a culture whereby the NHS has global health as a core component should make this possible. Finally, though these proposals specifically target UK training, the principles may be applicable to training schemes in other industrialised countries.

References

- 1.Department of Health. Global health partnerships: the UK contribution to health in developing countries - the Government response 2008. London: DH [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. Framework for NHS involvement in international development 2010. London: DH [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford L. MMC and overseas work. BMJ Careers 2009. Available from: http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20000007

- 4.Department of Health. Health is global: a UK government strategy 2008–2013 2008. London: DH [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alma Mata Global Health Careers Questionnaire 2009. Of 217 respondents who want to work in Global Health only 5% plan to work exclusively overseas. Results available from info@almamata.net

- 6.Mabey D. Improving health for the world's poor. BMJ 2000; 334: 1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitty CJM, Doull L, Nadjm B. Global health partnerships. BMJ 2007; 334: 595–6 10.1136/bmj.39147.396285.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molyneux M. UK doctors are already put off by changes in training. BMJ 2007; 334: 709–10 10.1136/bmj.39169.916296.1F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alma Mata global health careers questionnaire 2009. Of 217 respondents who want to work in global health, 44% felt that time out would harm their career or were unsure. Results available from info@almamata.net

- 10.British Medical Association. Broadening your horizons: a guide to taking time out to work and train in developing countries 2009. London: BMA [Google Scholar]

- 11. Personal communication, Philip Gothard, consultant in infectious diseases, University College London Hospital.

- 12.General Practice Training Recruitment. Working abroad at application time. GP Recruitment 2008. www.gprecruitment.org.uk/abroad.htm [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galukande M. Students whose behaviour causes concern: case history. BMJ 2009; 338: a2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanefield J, Musheke M. What impact do global health initiatives have on human resources for antiretroviral treatment roll-out? A qualitative policy analysis of the implementation process in Zambia. Human Resources Health 2009; 7: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medsin.org. Medsin-UK (Medical Students' International Network). www.medsin.org

- 16.Yudkin JS, Bayley O, Elnour S, Willot C, Miranda JJ. Introducing medical students to global health issues: a bachelor of science degree in international health. Lancet 2003; 362: 822–4 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14276-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alma Mata Working Group. Proposal for postgraduate training in global health for UK doctors. Alma Mata, 2009. www.almamata.net/news/system/files/Postgraduate%20training%20in%20Global%20Health%20Proposal.pdf

- 18.Volunteer scheme summary. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; www.rcpsych.ac.uk/members/internationalaffairsunit/volunteersprogramme/volunteerschemesummary.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evert J, Stewart C, Chan K, et al. Developing residency training in global health: a guidebook 2008. San Francisco: Global Health Education Consortium; www.globalhealtheducation.org/PublicDocs/GHEC%20Residency%20Guidebook.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.GHE/IM Residency. Boston: Brigham and Womens' Hospital; [2 June 2010]. www.brighamandwomens.org/socialmedicine/gheresidency.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tropical training. Amsterdam: Netherlands Society for Tropical Medicine and International; www.nvtg.org/index.php?id=136 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health partnership scheme terms of reference. London: UK Department for International Development; www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/procurement/tors-HPS.pdf [Google Scholar]