ABSTRACT

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) or sleeping sickness is a parasitic disease, acquired by the bite of an infected tsetse fly. In non-endemic countries HAT is rare, and therefore the diagnosis may be delayed leading to potentially fatal consequences. In this article the clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of the two forms of HAT are outlined. Rhodesiense HAT is an acute illness that presents in tourists who have recently visited game parks in Eastern or Southern Africa, whereas Gambiense HAT has a more chronic clinical course, in individuals from West or Central Africa.

KEYWORDS : Human African trypanosomiasis, sleeping sickness, Rhodesiense, Gambiense, non-endemic

Introduction

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) or sleeping sickness is a disease transmitted by the tsetse fly, affecting the poorest communities in sub-Saharan Africa. HAT is rare in non-endemic countries, and is therefore often not considered as the diagnosis, which can lead to serious complications, including death.

This article is aimed at clinicians in non-endemic countries. It provides a broad overview of HAT, focusing particularly on presentation and diagnosis (a useful learning tool can be found at www.braininfectionsuk.org/neuroid_elearning/).

Epidemiology

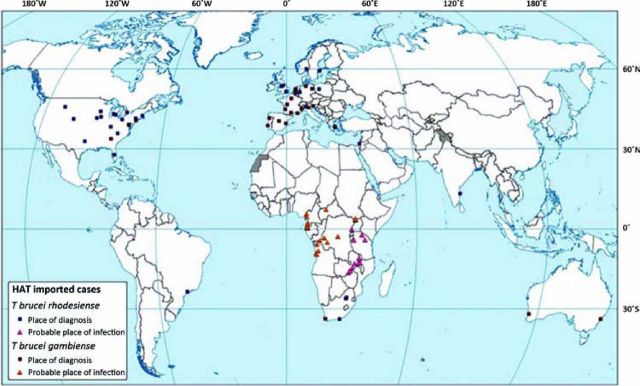

HAT is endemic to 36 African countries, occurring in highly specific foci in rural areas. Between 2000-2010, 94 HAT cases were reported in non-endemic countries (Fig 1). Specifically, 72% of cases were due to the East-African form (Rhodesiense HAT), and 28% due to the West-African form (Gambiense HAT),1 which is a reversal of the proportions attributable to each species in endemic areas.

Fig 1.

HAT cases diagnosed in non-endemic countries (2000–2010). HAT cases reported in non-endemic countries between 2000 and 2010 are illustrated on the map. Squares represent the place of diagnosis; triangles indicate the probable place of infection. Cases were compiled using a combination of published articles as well as those reported directly to the World Health Organization. Reproduced with permission.1 HAT = human African trypanosomiasis.

Fig 2.

Trypanosomal chancre on shoulder of patient. Reproduced with permission of Hospital Tropical Diseases.5

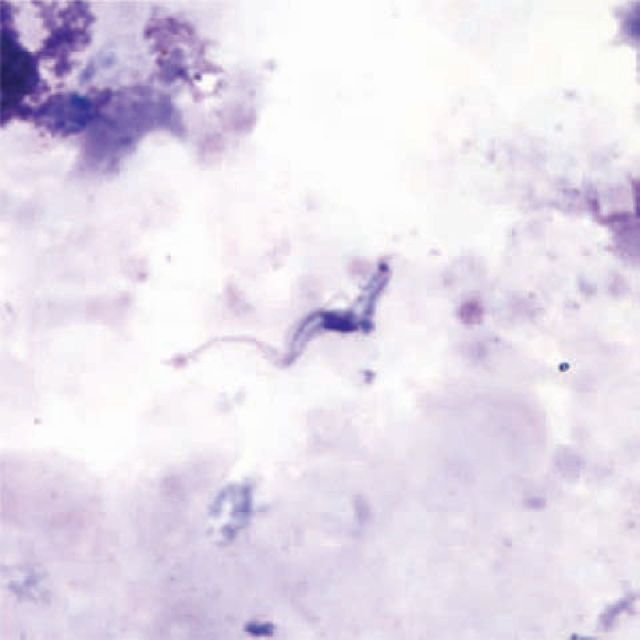

Fig 3.

Trypansoma brucei species in a thick blood smear stained with Giemsa. Reproduced with permission of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.8

Rhodesiense HAT classically occurs in tourists visiting the game parks of East and South Africa. Multiple individuals visiting the same area have been affected.2 In Gambiense HAT the main risk groups are migrants or long-term travellers.3 A detailed review of non-endemic cases of HAT over the last 20 years was performed by Migchelsen SJ et al in 2011.4

Clinical features

Classically, Gambiense HAT is a chronic infection lasting years, whereas Rhodesiense HAT is an acute presentation, progressing within weeks. In both diseases, clinical symptoms appear in two progressive stages; stage 1 (haemolymphatic stage) and stage 2 (meningoencephalitic stage), which occurs following entry of parasites into the central nervous system (CNS). Traditionally HAT is considered fatal without treatment.

However, there is increasing recognition that HAT is a diverse condition; the chronology of symptoms can vary widely and not all cases are fatal. This variability in presentation depends on multiple factors; including the specific parasite strain and the background of the host affected (travellers or migrants).3

Rhodesiense HAT

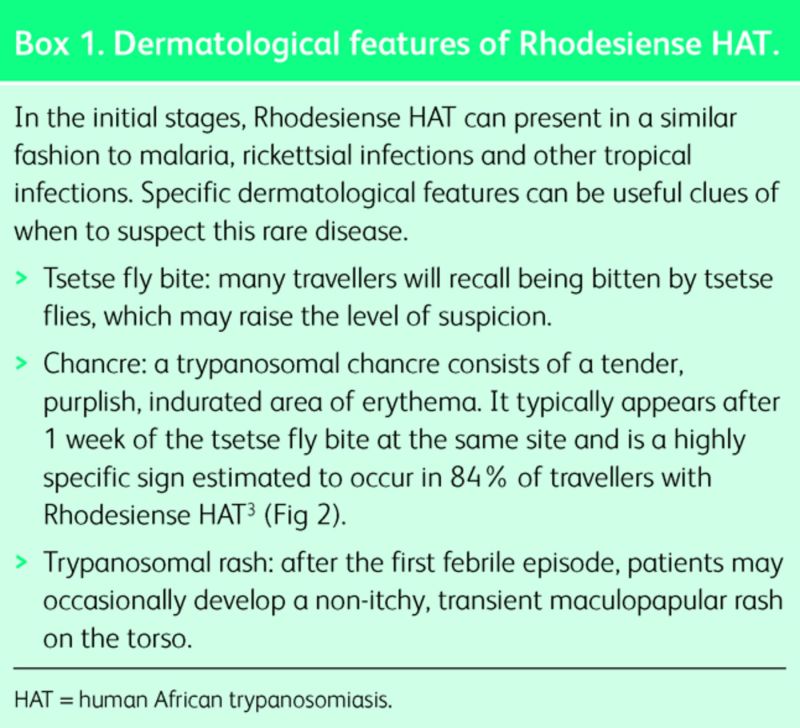

For the most part, Rhodesiense HAT presents as an acute febrile illness in travellers, with an incubation period of a few days to three weeks. Initial symptoms include high fever, headache, gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, vomiting and jaundice), lymphadenopathy and headache. Dermatological manifestations may be helpful discriminating features (Box 1).

Box 1. Dermatological features of Rhodesiense HAT.

As the illness progresses, patients may develop cardiac features which include myopericarditis and arrhythmias, as well as occasional neurological symptoms. In severe cases, patients develop signs of multiorgan failure following peaks of trypanosomal parasitaemia.6

Gambiense HAT

Migrants

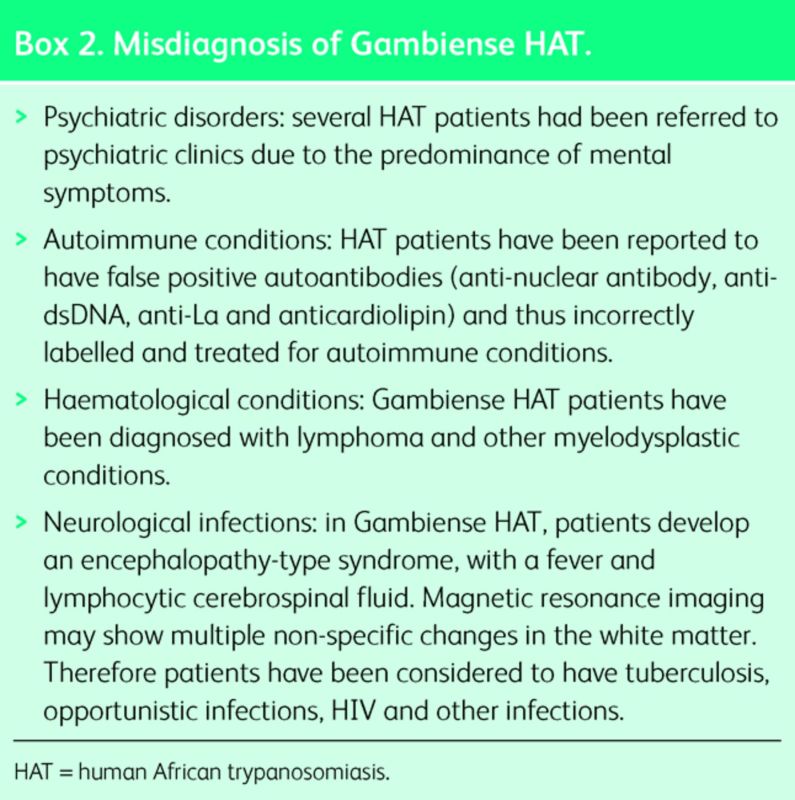

African migrants present with symptoms of Gambiense HAT many years after moving from the endemic area. Most cases present within seven years, but case reports show presentation 29 years after visiting an endemic area.7 The clinical presentation is characterised by low-grade fever and neuropsychiatric symptoms that can last months. Neurological features include a typical sleep disorder, motor and sensory disturbances, abnormal reflexes and psychiatric symptoms. The sleep disorder consists of reversal of the normal sleep–wake cycle and uncontrollable episodes of sleep. Motor disturbances include weakness, tremor and abnormal gait. Psychiatric features include low mood, hallucinations, delirium, anxiety and irritability. In the later stages if untreated, generalised meningoencephalitis leads to coma and death. Due to the long incubation period and indolent course, Gambiense HAT is often misdiagnosed initially1 (Box 2).

Box 2. Misdiagnosis of Gambiense HAT.

Travellers

In contrast to migrants, most travellers present with an acute febrile illness similar to Rhodesiense HAT with an incubation period of 1 month.9

Laboratory results

In both forms of HAT, blood tests may show anaemia and thrombocytopenia, impaired kidney and liver function, as well as raised inflammatory markers. HAT causes polyclonal gammaglobulinemia leading to markedly raised IgM levels10 which can lead to many cross-reacting antibodies7,11 (Box 2).

Diagnosis and staging

Visualisation of the parasite

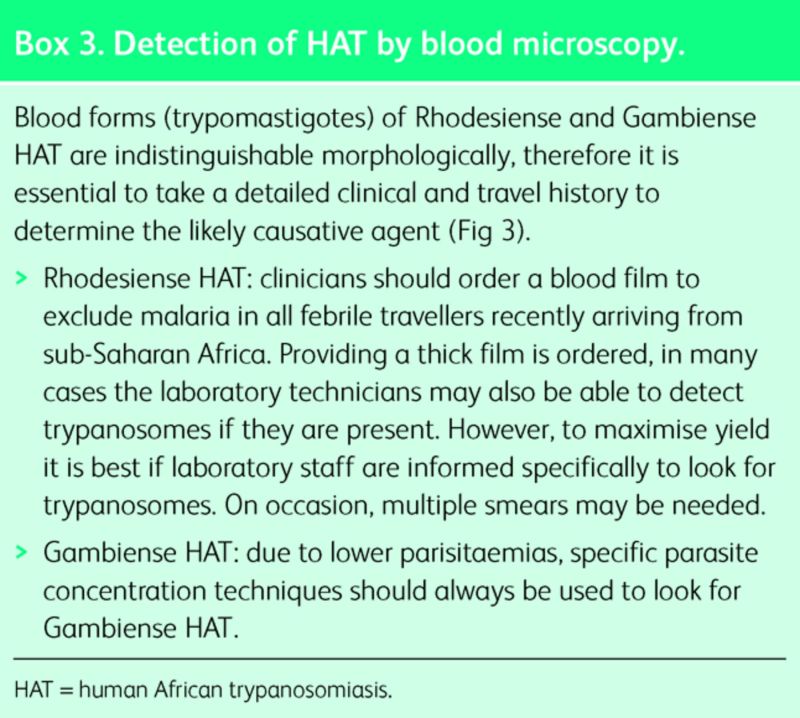

Definitive diagnosis of HAT requires microscopic demonstration of the parasite in peripheral blood, lymph node, chancre aspirate or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In the vast majority of cases, Rhodesiense HAT is diagnosed by thick blood film.12 Gambiense HAT is more challenging to diagnose in the blood (Box 3), so specimens from multiple sites should be taken. Serology (and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) if available) is useful when visualisation techniques have failed.

Box 3. Detection of HAT by blood microscopy.

Staging

Determination of CNS involvement is important to tailor therapy. Evidence of this is defined by either trypanosomes seen in CSF or increased CNS lymphocyte counts (>5 cells/μl).13 In Rhodesiense HAT, suramin therapy should be commenced immediately and lumbar puncture should be deferred until blood paristaemia has declined.6

Treatment and follow up

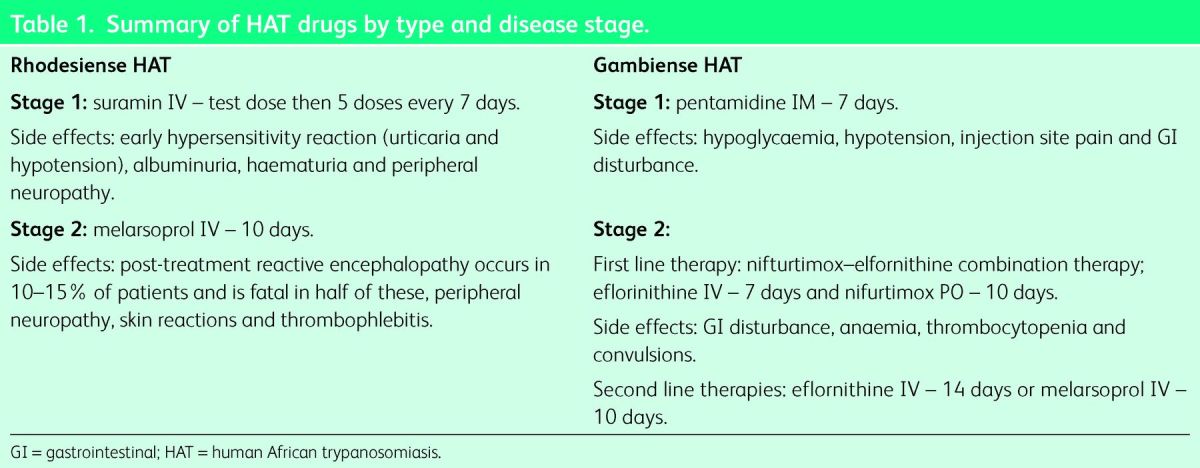

There are five licensed drugs for HAT, which are stocked in specialist tropical medicine centres in several non-endemic countries.1 If treatment is not readily available, drugs can be delivered free of charge from the World Health Organization (WHO) within 24–48 hours. Treatment depends on the type and stage of HAT13 (Table 1). All drugs are highly toxic and advice should be taken from tropical medicine specialists. Follow up for all patients is essential to ensure relapse does not occur.

Table 1.

Summary of HAT drugs by type and disease stage.

Preventative measures

Travellers visiting HAT endemic areas should be advised to take general protective precautions. The tsetse fly is active during daytime and is particularly attracted by motion and blue and black surfaces. Therefore, risk of exposure can be reduced by wearing full-length clothing with impregnation of permethrin, avoiding dark colours and regular application of skin repellent. A detailed report on the control and surveillance of HAT was published by the WHO in 2013.14

Key points.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) is a rare but serious condition that can be fatal if untreated.

Rhodesiense HAT is an acute aggressive illness with a high mortality. It should be considered in all febrile travellers who have recently visited safari parks in Eastern and Southern Africa.

Gambiense HAT presents in migrants with typical neurological symptoms, many years after departure from the endemic country. In travellers, Gambiense HAT may present with a more acute febrile illness.

The presentation of HAT is diverse and dependent on the parasite strain and the individual affected.

Advice should be sought early from a specialist centre to enable diagnosis and guide on management.

Declaration of Interest

References

- 1.Simarro PP, Franco JR, Cecchi G, et al. Human African trypanosomiasis in non-endemic countries (2000-2010). J Travel Med 19:44–53. 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00576.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gobbi F, Bisoffi Z. Human African trypanosomiasis in travellers to Kenya. Euro Surveill 2012;17:pii:20109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum JA, Neumayr AL, Hatz CF. Human African trypanosomiasis in endemic populations and travellers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2011;31:905–13. 10.1007/s10096-011-1403-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Migchelsen SJ, Buscher P, Hoepelman AI, et al. Human African trypanosomiasis: a review of non-endemic cases in the past 20 years. Int J Infect Dis 2011;15:e517–24. 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore DA, Edwards M, Escombe R, et al. African trypanosomiasis in travelers returning to the United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8:74–6. 10.3201/eid0801.010130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cottle LE, Peters JR, Hall A, et al. Multiorgan dysfunction caused by travel-associated African trypanosomiasis. Emerg Infect Dis 2012;18:287–9. 10.3201/eid1802.111479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudarshi D, Lawrence S, Pickrell WO, et al. Human African Trypanosomiasis presenting at least 29 years after infection – what can this teach us about the pathogenesis and control of this neglected tropical disease? PLos Negl Trop Dis, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Trypanosomiasis, African. Available online at www.cdc.gov/dpdx/trypanosomiasis African/index.html [Accessed 18 November 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urech K, Neumayr A, Blum J. Sleeping sickness in travelers – do they really sleep? PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011;5:e1358. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whittle HC, Greenwood BM, Bidwell DE, Bartlett A, Voller A. IgM and antibody measurement in the diagnosis and management of Gambian trypanosomiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1977;26:1129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meltzer E, Leshem E, Steinlauf S, Michaeli S, Sidi Y, Schwartz E. Human African trypanosomiasis in a traveler: diagnostic pitfalls. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;87:264–6. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wise E, Easom N, Watson J, Bailey R, Brown M. Lesson of the month: a psychiatric diagnosis overturned by a blood film. Clin Med 2011;12:295–6. 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-3-295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Control and surveillance of human African trypanosomiasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 20131–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Control and surveillance of human African trypanosomiasis. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Technical Report Series. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]