ABSTRACT

The diagnosis of rabies encephalitis relies on awareness of the varied clinical features and eliciting a history of unusual contact with a mammal throughout the endemic area. The diagnosis is easily missed. Laboratory tests are not routine and only confirm clinical suspicion. Rabies infection carries a case fatality exceeding 99.9%. Palliation is appropriate, except for previously-vaccinated patients or those infected by American bats, for whom intensive care is probably indicated. However, as rabies vaccines are outstandingly effective, no one should die of dog-transmitted infection. Vaccines and rabies immunoglobulin are expensive and usually scarce in Asia and Africa. All travellers to dog rabies enzootic areas should be strongly encouraged to have pre-exposure immunisation before departure. There is no contraindication to vaccination but the cost can be prohibitive. Intradermal immunisation, using 0.1 ml and sharing vials of vaccine, is cheaper and is now permitted by UK regulations. Returning travellers may need post-exposure prophylaxis. Economical intradermal post-exposure vaccination is practicable and should be introduced into rural areas of Africa and Asia immediately. Eliminating rabies in dogs is now feasible and would dramatically reduce human mortality, if funds were made available. The high current economic burden of human prophylaxis would then be largely relieved.

KEYWORDS : rabies vaccine, lyssavirus, bat, dog, encephalitis

Key points

Any mammal can transmit rabies but dog rabies virus causes 99% of human rabies deaths

Only pre-exposure immunisation followed by post-exposure boosting has provided complete protection against disease

Only one unvaccinated person and two partially-vaccinated ones have recovered from rabies encephalomyelitis for which there is no specific antiviral treatment

Intensive care is appropriate in very few cases, only, perhaps, those previously immunised and those infected with American bat rabies virus, which may be less pathogenic in humans

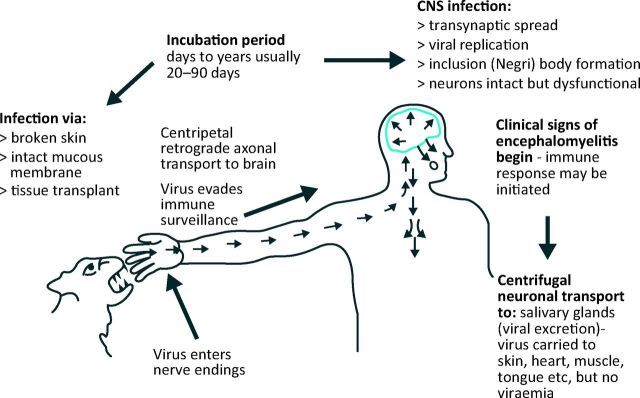

Rabies virus causes fatal encephalomyelitis in humans. It is one of 12 species of the Lyssavirus genus.1 The other species, mainly of bats, are rabies-related lyssaviruses that may be equally pathogenic.2–4 Rabies infection should be entirely preventable. However, when effective treatment is unavailable, unaffordable, delayed or incomplete, virus inoculated into a bite wound can ascend intraneuronally to the brain5 resulting in fatal encephalomyelitis (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Rabies pathogenesis.

Epidemiology

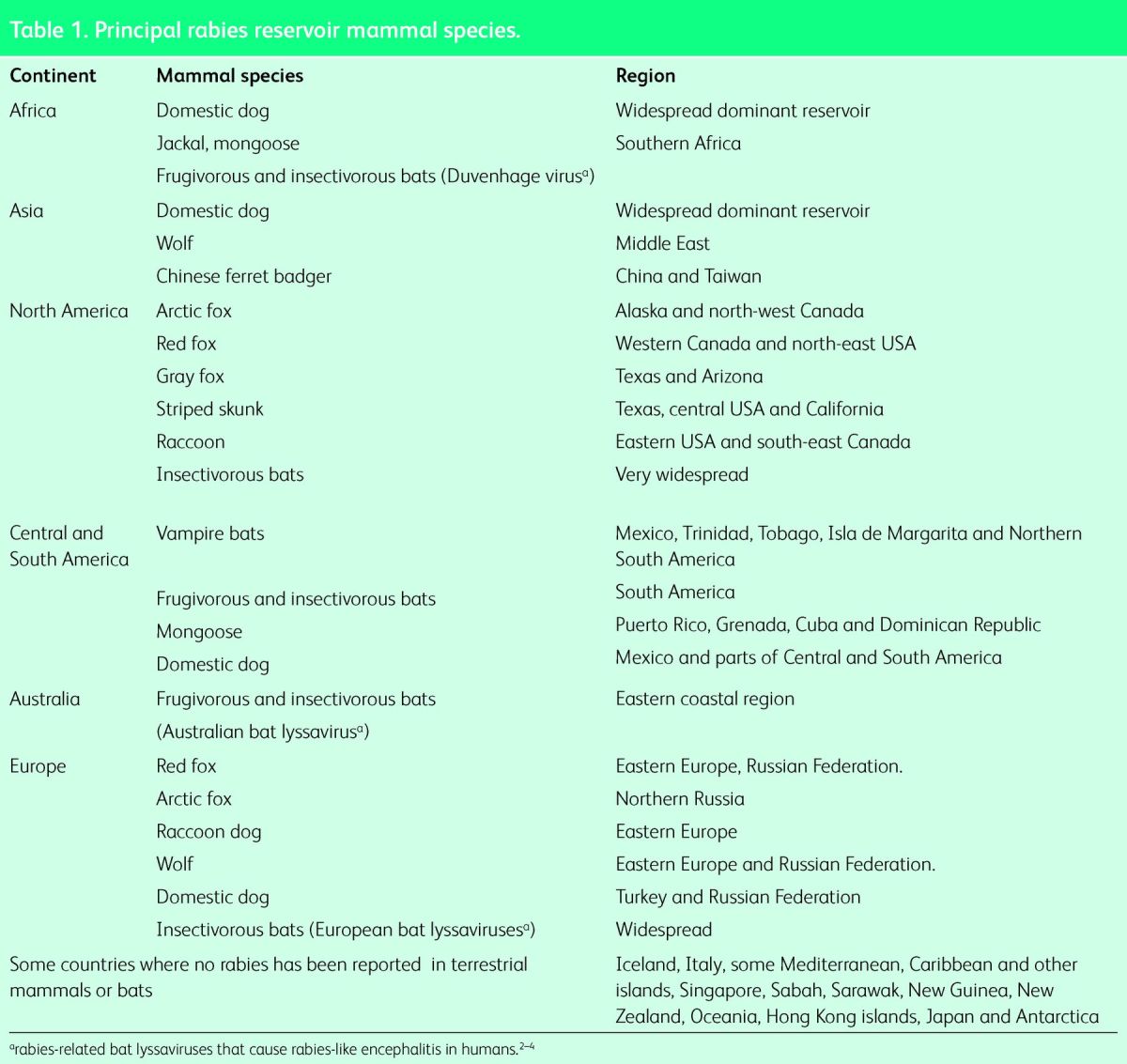

Dogs, the main rabies reservoir species, usually infect by an unprovoked bite. Wild mammals such as foxes, raccoons, skunks and wolves are also reservoirs in certain countries and lyssavirus infection of bats has been detected everywhere it has been sought (Table 1). Canine rabies virus causes 99% of the human deaths.6 All mammals are susceptible to rabies and are potential vectors (able to transmit the virus) including cats, other domestic animals but rarely monkeys.7 Bites by rodents carry a very low risk.

Table 1.

Principal rabies reservoir mammal species.

Clinical rabies encephalomyelitis

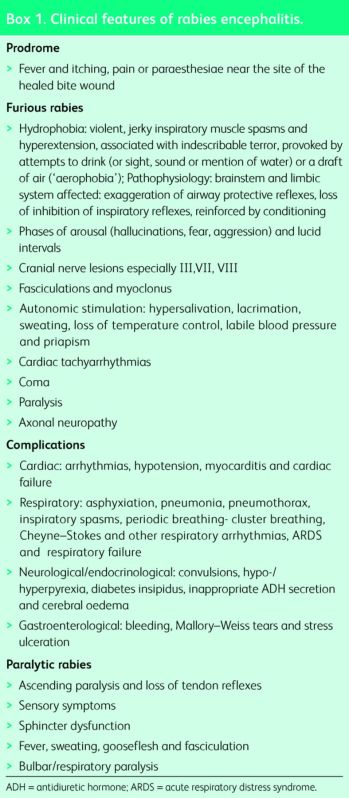

Early recognition depends on eliciting a history of a bite or other contact with a possibly infected mammal, most commonly in dog rabies endemic areas of Asia, Africa or South America. There is a wide range of non-specific prodromal symptoms, so rabies patients have presented to rheumatologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, cardiologists, respiratory and acute medicine physicians, ear, nose and throat specialists, general and transplant surgeons8 and GPs. The main clinical features9,10 are listed in Box 1.

Box 1. Clinical features of rabies encephalitis.

Prognosis

Without intensive care, unvaccinated victims of furious rabies encephalomyelitis die within a few days, but patients with paralytic rabies may survive for weeks.

Ten case reports of prolonged survival or recovery from rabies have been published.11,12 In all but one, one or more doses of vaccine had been received, post- or pre-exposure. Diagnoses were based on detection of very high neutralising antibody levels, or, rarely, by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or antigen detection. Among the three recoveries, two had been vaccinated after a dog11 or bat13 bite, and one unvaccinated patient recovered from a bat infection.14 American bat rabies viruses may be less pathogenic in humans. All other survivors suffered severe neurological sequelae.12 No unvaccinated patient infected by a dog or other terrestrial mammal is known to have recovered from rabies encephalitis. Patients who recovered showed early development of neutralising antibody.

Diagnosis

Rapid diagnosis of rabies encephalomyelitis intra vitam is possible by PCR on saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, respiratory secretions, tears and skin biopsies and by immunofluorescent staining of skin sections. Daily samples should be tested until a diagnosis is confirmed. Virus isolation is ideal but takes days. Unvaccinated patients can be diagnosed by finding neutralising antibody. Contact the destination laboratory before taking samples.

Management

Partially-documented cases of human rabies survival, reported over the last 40 years, have provided hope that rabies encephalomyelitis might be treatable. However no specific treatment has proved effective. Rabies of canine origin remains 100% fatal in unvaccinated people. Patients should be admitted to hospital so that their agonising symptoms can be palliated with adequate doses of analgesic and sedative drugs.15 Those contaminated by patient saliva should be given prophylaxis. Hospital staff or carers are vaccinated for reassurance. Intensive care may be appropriate in previously vaccinated patients, or those infected by an American bat virus, especially those presenting early with detectable rabies antibody.

Prophylaxis

Rabies vaccine is usually given after exposure to a possibly rabid mammal, but it is more effective if used beforehand. The combination of pre-exposure immunisation followed by post-exposure boosting has proved 100% effective.

Pre-exposure vaccination

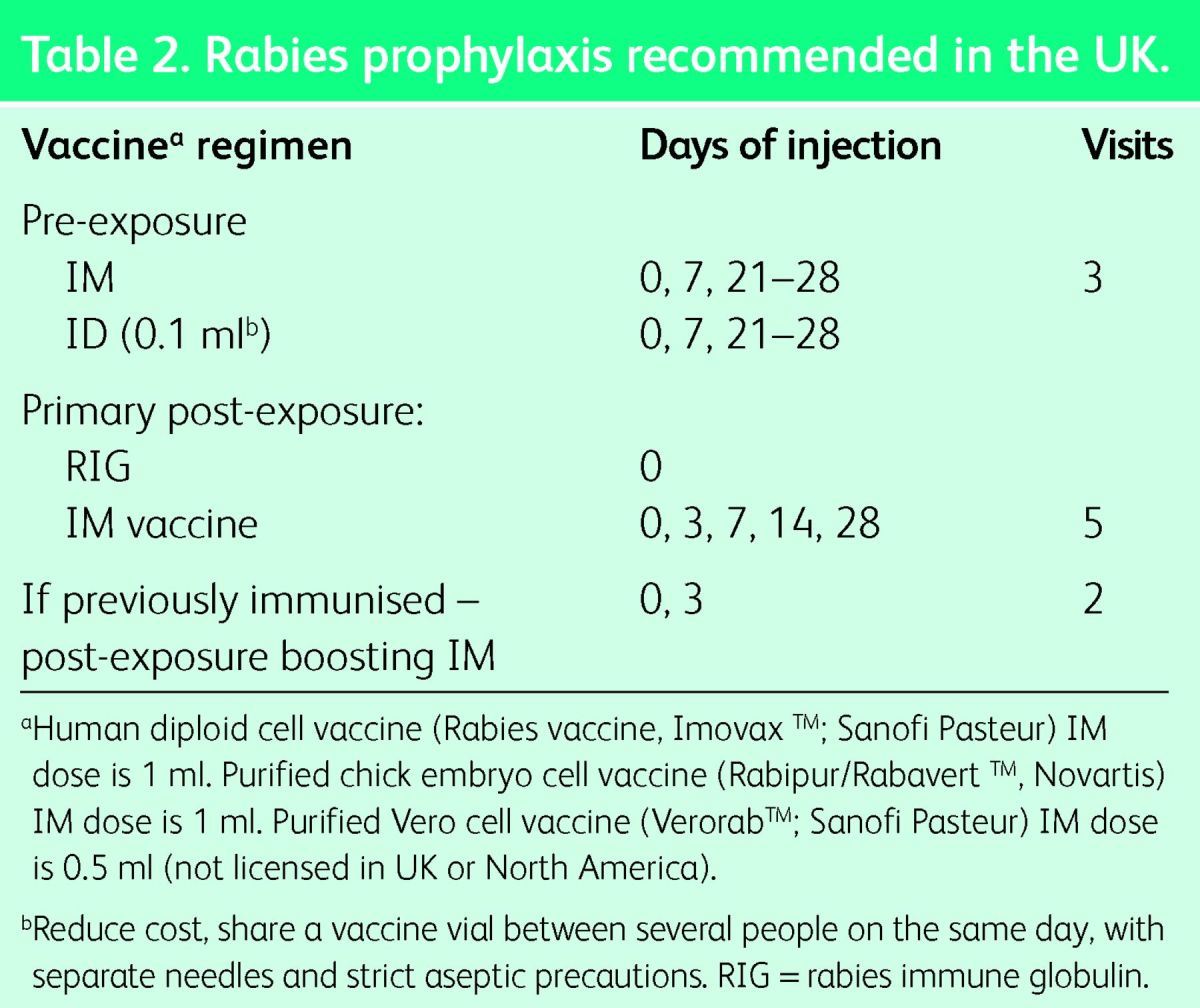

Pre-exposure vaccination is recommended for anyone at risk of contact with a rabid domestic or wild mammal. Contact with a bat anywhere in the world constitutes a possible risk. Travellers should avoid dogs, cats and wild mammals in rabies enzootic areas. A pre-exposure vaccine course is required only once in a lifetime. It is strongly recommended for travellers to, and residents of, countries with dog rabies,16 and for those at risk through occupation or leisure activities. To reduce the cost, this vaccine can be injected ID. The pre-exposure vaccine regimen is three doses: on days 0, 7 and 28, either one vial IM or 0.1 ml ID in the deltoid area (Table 2).6 The timing of the final dose can be delayed or advanced to day 21. The vaccine must be given IM if immunosuppression is suspected, including by chloroquine medication. The UK regulations permit ID injection by suitably qualified and experienced healthcare professionals with warnings about the prescriber's responsibility and the risk of contamination of vials.17

Table 2.

Rabies prophylaxis recommended in the UK.

If there is insufficient time for a full vaccine course before travel, give one or two doses. Having had any vaccine previously is better than none if you are exposed to rabies. The course can be completed later. Booster doses of pre-exposure vaccine are not normally required for travellers if they will have access to vaccine for post-exposure boosting if needed. If vaccine will not be rapidly available, a single booster dose after 5 years is advisable.18 Booster doses are recommended for people at occupational or high risk of exposure.6,19

Post-exposure vaccination

Post-exposure treatment is given if a possibly rabid mammal bites or scratches, or licks a mucous membrane. Wound cleaning, rabies vaccination and rabies immune globulin (RIG) are urgently required. However, it is never too late to start treatment. There is no contraindication to post-exposure therapy. Wash the wound thoroughly with soap or detergent and water and apply povidone iodine. For those previously immunised with at least three doses of vaccine, RIG treatment is not necessary but post-exposure boosting is essential using two doses on days 0 and 3 (Table 2). The primary postexposure vaccine regimen in the UK is the IM (‘Essen’) regimen of five doses on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28 into the deltoid (Table 2).18 Outside the UK, other IM and ID post-exposure regimens are used. High costs and limited supplies of vaccine result in many preventable deaths. Many lives could be saved if safe, economical ID vaccine regimens were accepted globally.18

Passive immunisation neutralises virus in the wound, providing crucial protection during the 7–10 days before vaccine induced immunity appears. RIG is not needed if vaccine had been started >7 days previously. Local analgesia is advisable before injection. A dose of human RIG, 20 U/kg body weight, should be infiltrated into and around the wound. If this is impossible, for example in a finger, give the rest IM, preferably into the anterolateral thigh, but not the gluteal region. There is a global shortage of RIG. It is not available in several countries and many rural areas.

Solving the problem of human rabies?

Dog rabies can be eliminated by mass vaccination and contraception for stray dogs. This is the best and most economical way of preventing human rabies in the long term.20

References

- 1.Calisher CH, Ellison JA. The other rabies viruses: The emergence and importance of lyssaviruses from bats and other vertebrates. Travel Med Infect Dis 2012;10:69–79. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathwani D, McIntyre PG, White K, et al. Fatal human rabies caused by European bat Lyssavirus type 2a infection in Scotland. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:598–601. 10.1086/376641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Thiel PP, de Bie RM, Eftimov F, et al. Fatal human rabies due to Duvenhage virus from a bat in Kenya: failure of treatment with coma-induction ketamine and antiviral drugs. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009;3:e428. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis JR, Nourse C, Vaska VL, et al. Australian Bat Lyssavirus in a child: the first reported case. Pediatrics 2014;133:e1063–7. 10.1542/peds.2013-1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnell MJ, McGettigan JP, Wirblich C, Papaneri A. The cell biology of rabies virus: using stealth to reach the brain. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010;8:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies. Second report. World Health Organization technical report series 982. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gautret P, Blanton J, Dacheux L, et al. Rabies in nonhuman primates and potential for transmission to humans: a literature review and examination of selected French national data. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8:e2863. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vora NM, Basavaraju SV, Feldman KA, et al. Raccoon rabies virus variant transmission through solid organ transplantation. JAMA 2013;310:398–407. 10.1001/jama.2013.7986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warrell DA. The clinical picture of rabies in man. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1976;70:188–95. 10.1016/0035-9203(76)90037-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greer DM, Robbins GK, Lijewski V, Gonzalez RG, McGuone D. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 1-2013. A 63-year-old man with paresthesias and difficulty swallowing. N Engl J Med 2013;368:172–80. 10.1056/NEJMcpc1209935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson AC. Recovery from rabies: a call to arms. J Neurol Sci 2014;339:5–7. 10.1016/j.jns.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Souza A, Madhusudana SN. Survival from rabies encephalitis. J Neurol Sci 2014;339:8–14. 10.1016/j.jns.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hattwick MAW, Weis TT, Stechschulte CJ, Baer GM, Gregg MB. Recovery from rabies: a case report. Ann Intern Med 1972;76:931–42. 10.7326/0003-4819-76-6-931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willoughby RE, Jr, Tieves KS, Hoffman GM, et al. : Survival after treatment of rabies with induction of coma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2508–14. 10.1056/NEJMoa050382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson AC, Warrell MJ, Rupprecht CE, et al. Management of rabies in humans. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:60–3. 10.1086/344905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautret P, Parola P. Rabies in travelers. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2014;16:394. 10.1007/s11908-014-0394-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health Rabies. In: Immunisation against infectious disease 2006 – The Green Book. London: Department of Health; 2013:329–45. Available online at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/85762/Green-Book-Chapter-27-v3_0.pdf [Accessed July 24 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warrell MJ. Current rabies vaccines and prophylaxis schedules: -preventing rabies before and after exposure. Travel Med Infect Dis 2012;10:1–15. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manning SE, Rupprecht CE, Fishbein D, et al. Human rabies -prevention – United States 2008: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep 2008;57(RR-3):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitzpatrick MC, Hampson K, Cleaveland S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of canine vaccination to prevent human rabies in rural Tanzania. Ann Intern Med 21 2014;160:91–100. 10.7326/M13-0542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]