Abstract

Advocacy, policy, research and intervention efforts against childhood pneumonia have lagged behind other health issues, including malaria, measles and tuberculosis. Accelerating progress on the issue began in 2008, following decades of efforts by individuals and organizations to address the leading cause of childhood mortality and establish a global health network. This article traces the history of this network’s formation and evolution to identify lessons for other global health issues. Through document review and interviews with current, former and potential network members, this case study identifies five distinct eras of activity against childhood pneumonia: a period of isolation (post WWII to 1984), the duration of WHO’s Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) Programme (1984–1995), Integrated Management of Childhood illness’s (IMCI) early years (1995–2003), a brief period of network re-emergence (2003–2008) and recent accelerating progress (2008 on). Analysis of these eras reveals the critical importance of building a shared identity in order to form an effective network and take advantage of emerging opportunities. During the ARI era, an initial network formed around a relatively narrow shared identity focused on community-level care. The shift to IMCI led to the partial dissolution of this network, stalled progress on addressing pneumonia in communities and missed opportunities. Frustrated with lack of progress on the issue, actors began forming a network and shared identity that included a broad spectrum of those whose interests overlap with pneumonia. As the network coalesced and expanded, its members coordinated and collaborated on conducting and sharing research on severity and tractability, crafting comprehensive strategies and conducting advocacy. These network activities exerted indirect influence leading to increased attention, funding, policies and some implementation.

Keywords: Child survival, networks, pneumonia

KEY MESSAGES.

The global health network for childhood pneumonia did not fully emerge until its members assumed a shared identity that welcomed a broad group of actors focused on the issue.

Prior to establishing a shared identity and network structures, the actors involved in pneumonia efforts demonstrated only limited ability to take advantage of political opportunities.

Defining and building a shared identity is a prerequisite for efforts to build effective global health networks.

Introduction

Pneumonia kills more children than any other disease, and is responsible for about the same share of global mortality as HIV/AIDS (Lozano et al. 2013; see Table 1 below). Yet despite the substantial impact and distribution of pneumonia burden, funding and attention to the disease at the global level is very limited. When compared with its fellow lung disease, tuberculosis, or to the third leading killer of children, malaria, this disparity becomes even more remarkable. Despite posing a greater global burden of disease, pneumonia receives far less media attention and funding than either of these other diseases (Shiffman 2006; Hudacek et al. 2011). In the 1980s, pneumonia appeared to occupy a similar position of potential support as the other two diseases, with dedicated global and national programs. Unlike malaria and TB, which formed effective global health initiatives in Roll Back Malaria (van Ballegoyen 1999; Bates and Herrington 2007) and Stop TB (Ogden et al. 2003; Quissell and Walt 2016), pneumonia efforts and network formation initially stalled. Until the middle of the last decade, limited impact on advocacy or policy, let alone effective scale-up of interventions, emerged from the global community of activists, policy makers and researchers working on pneumonia. Recent advances, in network formation, advocacy efforts, policy adoption and research—on vaccines, other interventions, risk factors and the epidemiology and aetiology of the disease—reinvigorated network formation and rapidly accelerated the pace of some efforts against pneumonia. This raises the question of why these efforts, particularly the formation of a network focused on pneumonia, took longer to develop and then what changed to enable more recent progress.

Table 1.

Global mortality of select infectious diseases in 2010

| Disease | Deaths, 1000s |

|---|---|

| All lower respiratory infections | 2814 |

| Pneumonia | 1461 |

| Diarrheal Diseases | 1446 |

| HIV/AIDS | 1465 |

| Tuberculosis | 1196 |

| Malaria | 1170 |

| Meningitis | 423 |

| Other childhood illnesses (Malaria, Tetanus, Whooping Cough, Varicella, Diphtheria) | 278 |

Data Source: Lozano et al. (2013).

Understanding issue prioritization requires far more than looking at just disease characteristics, the content and design of policies and outcome measurement. It also requires attention to the actors and processes (Walt and Gilson 1994; Shiffman and Smith 2007) by which policies are crafted, adopted and implemented, through which issue characteristics are interpreted and even shaped (Shiffman 2009) and that define methods and subjects of measurement. Actors and processes have too often been overlooked in global health policy research (Walt and Gilson 1994) and require investigation, especially networks.

This study examines the advocacy and policy network formed around childhood pneumonia. Two thirds of adult (Fedson et al. 1999) and 99% of child (Rudan et al. 2008) mortality from pneumonia is estimated to occur in low and middle income countries (LMIC). In LMICs, estimated childhood pneumonia mortality (Garenne et al. 1992; Black et al. 2003) is at least twice that of adults (Fedson et al. 1999). On both equity and total mortality grounds, adult pneumonia is significantly less of a crisis in developing countries than amongst children, justifying the network limiting its focus to children. Childhood pneumonia mortality estimates dropped in half over the past decade and a half, from 2.1 million (Black et al. 2003) to 0.9 million (Liu et al. 2015), but it remains the leading infectious cause of childhood mortality.

Pneumonia is an acute respiratory infection (ARI), a communicable disease affecting the lungs that is caused by a range of infectious agents. Amongst children, two families of bacteria, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, account for approximately 70% of cases, while the fungus Pneumocystis jiroveci is a leading cause of infections amongst HIV positive children (Jeena 2008; O’Brien et al. 2009; Watt et al. 2009). Other bacterial and viral agents comprise the remainder of cases. Despite pneumonia’s biological complexity, strategies for prevention, diagnosis and treatment of childhood pneumonia are well-known, non-controversial and easily applied in settings with access to appropriate medical care. Prevention can occur through Hib and pneumococcal vaccines that directly address pneumonia (Madhi et al. 2008), measles and pertussis vaccines to limit potential causes of secondary infections (UNICEF and WHO, 2006), nutrition for pregnant mothers and infants (César et al. 1999; Caulfield et al. 2004) and limiting exposure to cooking (Smith et al. 2011) and tobacco smoke (Kirkwood et al. 2005). Radiology is held as the optimal diagnosis mechanism (Cherian et al. 2005), though in settings lacking access, observations of respiration are used (Rasmussen et al. 2000). Antibiotics are used to treat pneumonia (Bari et al. 2011) and severe cases require oxygen therapy (Enarson et al. 2008). With these interventions known and potentially available, the disease could be expected to be of limited impact on children (Bhutta et al. 2013). Yet it remains the leading single killer of children, accounting for 15% of early deaths (Liu et al. 2015). Understanding why the network was delayed in forming and addressing this problem can inform network formation and collective action for other health issues.

This study situates network creation and activity within the broader history and environment of pneumonia control efforts, examines the strategies selected by network members and seeks to identify the network’s involvement in progress on pneumonia control. Through interviews with key global leaders on the disease and in-depth document review, this article aims to develop a narrative of this network’s history. Using this narrative to examine why efforts and network formation were initially delayed and then accelerated rapidly can identify lessons relevant to child survival and global health policy more broadly.

Conceptual framework

This study is part of the Global Health Advocacy and Policy Project (GHAPP), a research initiative examining networks that have mobilized to address six global health problems: tuberculosis, pneumonia, tobacco use, alcohol harm, neonatal mortality and maternal mortality. Its aim is to understand why networks crystallize surrounding some issues but not others, and why some are better able to influence policy and public health outcomes. GHAPP studies draw on a common conceptual framework grounded in theory on collective action from political science, sociology and economics (Snow et al. 1986; Stone 1989; Kingdon 1994; Keck and Sikkink 1998; Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Marsh and Smith 2000; McAdam et al. 2003; Kahler 2009). The introductory article to this supplement presents the framework in detail (see Shiffman et al. 2016).

This article, like the other GHAPP studies, defines networks broadly as organizations that fall outside the expected structures of hierarchies or markets (Podolny and Page 1998). Global health networks can emulate epistemic communities by contributing to the generation and spread of knowledge (Adler and Haas 1992), global public policy networks by seeking to inform the design and implementation of policies (Reinicke 1999; Stone 2004), transnational advocacy networks by undertaking advocacy to influence the norms held by nations and other organizations (Keck and Sikkink 1998), and social movements by building grassroots support (Benford and Snow 2000; Tilly 2005). In this article, network does not presume to refer to any one of these specific forms, but could involve elements of any or all of them. The term network is also treated as dynamic and used in reference to the childhood pneumonia network at a given time.

The GHAPP studies examine network outputs, policy consequences and impact. Outputs are the immediate products of network activity, such as guidance on intervention strategy, research and international meetings. Policy consequences pertain to the global policy process, including international resolutions, funding, national policy adoption and the scale-up of interventions. Impact refers to the ultimate objective of improvement in population health.

The framework consists of three categories of factors (Shiffman, et al. 2016). The category network and actor features includes factors internal to the network and attributes of actors central to it. This category pertains to how networks and the individuals and organizations that create and comprise them exercise agency, and includes leaders, governance, composition and framing strategies. A second category, the policy environment, concerns factors external to the network that shape its nature and impacts, including potential allies and opponents, funding and norms. The third category, issue characteristics, concerns features of the problem the network seeks to address. The idea is that issues vary on a number of dimensions, such as severity, tractability and the nature of affected groups, that make them more or less difficult to tackle. GHAPP studies begin with the presumption that no single category of factors is determinative: rather factors in each of the three interact with one another to shape policy and public health effects. This article addresses substantial variation over time in both attention to childhood pneumonia and network characteristics, allowing for examination of interactions between the framework factors.

Network formation and emergence can be understood as a process influenced by identities shared between potential network members, structures of interactions between them and changes in the policy environment. Identity is central to scholarship on social movements, serving to unite and mobilize a range of actors in pursuit of a common goal (McAdam et al. 2001; Staggenborg 2002; Tilly 2005). Rooted in individuals and their relationships to one another, identities establish boundaries between groups and serve as the potential common ground for network membership. Actors with shared identities form bonds and social ties even in the absence of formal structures. During periods of quiet, these ‘weak’ ties serve to unify actors, establish the potential for future action, establish trust, share information (Granovetter 1973; Staggenborg 2002), identify preferred solutions and frame messages to influence others (Snow et al. 1986; Benford and Snow 2000). Then when the environment shifts to become more supportive of an issue, those sharing collective identities can rapidly shift into activity (McAdam et al. 2001; Staggenborg 2002), alter issue frames for a broader appeal (Snow et al. 1986) and add network members (Agranoff and McGuire 2001).

Issue characteristics are socially constructed and can be altered by efforts of network members. Although attention to issues does not correlate directly to any given measure of importance, such as severity (Hilgartner and Bosk, 1985), evidence and perception of an issue’s severity may serve as necessary, but not sufficient condition for an issue to gain attention. Perceptions of issue severity rely on both scientific evidence (Stone 1989) and diagnostic framing to share this evidence (Benford and Snow 2000). Frames that establish perceptions of public health risk (Nathanson 1996) or a public responsibility to address the issue (Gusfield 1989) may be more successful in attracting attention. The portrayal of those affected by the issue also may influence the attention to issues: risks to outsiders are dismissed while universal risks and those that affect the powerful, positively regarded or perceived as innocent are accepted (Nathanson 1996; Schneider and Ingram 1993; Nathanson 2007). The shared identity of a network influences the range of solutions and issue framing strategies its membership finds acceptable, which in turn has implications for the extent to which others perceive the issue as tractable. As with severity, perceptions of tractability require scientific evidence (Adler and Haas 1992) and framing strategies that convince others of chosen interventions’ effectiveness (Benford and Snow 2000). Network members thus contribute to influencing perceptions of severity and tractability by creating scientific evidence, sharing knowledge, championing interventions and framing the issue.

Environmental shifts and structures create the potential for issues to rapidly gain attention. The venues (or arenas) through which attention to issues is allotted, such as donor agencies, international organizations and media outlets, demonstrate linkages with one another, which allows for issues to rapidly spread across these channels, once they start receiving enough attention from various sources (Hilgartner and Bosk 1985). Changes in the political (Kingdon 1984; Nathanson 2007), cultural (Benford and Snow 2000) or normative (Stone 2004) contexts create windows of opportunity for shifts in attention to issues; when networks or other proponents of issues successfully leverage these opportunities, stable periods of equilibrium are punctuated and result in major changes (Baumgartner and Jones 1993). Although networks and their members may have limited direct influence on these broader changes, their strategies and characteristics may influence the extent to which they can take advantage of opportunities as they arise. ‘Proponents [who] have visibility, access to media and prominent positions’ (Stone 1989, p. 294) or the presence of elite sponsors (Hilgartner and Bosk 1985) enable networks to access these opportunities. Networks with greater inclusivity and flexibility may also be better able to establish bridges linking to other issues and access political and cultural opportunities (Benford and Snow 2000). Such diverse networks, in terms of national and professional perspectives, may lead to better overall outcomes by drawing on a broader range of information and alternatives (Hong and Page 2004; Page 2007).

From this literature, we can expect to observe network formation only after deliberate efforts to develop a shared identity, an issue frame and evidence of tractability and severity. Tensions between the ease of developing a narrow identity and drawing on a diverse potential membership will arise, and may be shaped by environmental and issue characteristics. Successful networks would continue to revise their identity, frames and evidence base to shape perceptions of issue characteristics, attract members and take advantage of emerging opportunities. Finally, we can also expect successful networks to align their activity and framing strategies to leverage their strengths and fit within the broader environment of competing issues and power dynamics.

Methods

Using a process-tracing methodology, this study conducted in-depth examination of social and political processes in order to uncover causal mechanisms that led to network formation, attention and progress on the issue (Yin 2003; George and Bennett 2005). Using this methodology, multiple primary and secondary sources were drawn upon to triangulate findings and build a cohesive causal narrative. The aim was to trace in detail the role of networks, environments, issue characteristics and other factors in shaping agenda-setting, policy formulation, policy implementation and mortality and morbidity change. During the course of the study, it became apparent that network formation and involvement served as an important measure of attention to the issue within the scientific and international organization communities. As a result, earlier network characteristics like composition and structure help explain later variations in attention and network characteristics.

This article’s sources of information included extensive document review of scholarly publications, reports and organizational websites and a series of semi-structured interviews. The document review began with searches of PubMed, Google Scholar and Google to identify the most influential articles, reports, websites, organizations and individuals. References from key items and recommendations by interviewees expanded this initial set of documents to 295 publications. A noticeable gap emerged from these documents: availability of data on network impacts. Funding data is partial and fragmented, mortality estimates are intermittent (particularly in the 1980s and 1990s) and data on policy and implementation is available only for some interventions.

Initial document review led to a list of critical individuals and organizations to target for interviews, which snowball sampling expanded. Selective recruiting added views from other subjects who shared an interest in childhood pneumonia but were less involved in the network. This study intentionally did not include other actors, like donors and national-level policy-makers, who could be considered part of the network’s external environment rather than potential members. Care was taken to ensure ethical treatment of interview subjects, including free and informed consent of respondents and internal review board exemption from Syracuse University. Interviews with 24 respondents—11 from academic institutions, 7 from NGOs and 6 from international or governmental agencies—were conducted in-person, over the phone and via Skype. The interviews were recorded with respondent permission, began with a basic set of questions on the progress, events, environment, actors and interventions relevant to pneumonia and were individually tailored to draw on unique expertise and knowledge.

Analysis of this data progressed inductively and iteratively. Early interviews and document review led to an initial timeline of major events and map of key actors, which later interviews and rounds of feedback modified and improved. Where prior interviews raised new questions about how events and factors influenced future activities and outcomes, probing questions and respondent feedback sought to fill in gaps in the narrative. Triangulation of multiple diagnostic pieces of evidence, within case variation over time and some counterfactual comparisons provided evidence and support for the narrative and its implications.

The author is an outsider to the network, which provided the advantage of lacking any pre-existing biases or assumptions about progress on the issue. This status also required that the case study incorporate substantial feedback from those with greater expertise and exposure to the issue and network. Drafts of the case, timeline and actor map were shared with network members, authors of the other cases and elsewhere in the global health community to examine the reliability of initial findings, sharpen this analysis and correct any factual or interpretive inaccuracies in the narrative.

Results

Examination of the global advocacy, policy and research network on childhood pneumonia reveals five distinct eras, with different network structures, types of actors involved, technological advances, external opportunities and outcomes (see Table 2, below). These eras also illustrate a gradual and lengthy process of network emergence and shared identity formation. Potential network members tended to operate in relatively isolated groups focused on particular interventions, which made developing a shared identity and strong network governance structures difficult. Between the end of World War II and the early 1980s, high income country attention to pneumonia waned while attention to the disease in LMICs was diffused, lacking a global network or shared identity. From 1984 until 1995, a network on pneumonia began to form, with global and national programs dedicated to the issue and built around shared identities of community-level care for this disease. The 1995 switch by the World Health Organization (WHO) to an integrated approach for childhood illness led to a dissipation of this fledgling network for a decade, as the narrow identity left network members little voice in the broader cross-disease effort. Beginning in 2003, influential actors returned attention to the disease and began to rebuild the network around a broader identity encompassing the full spectrum of related interventions and growing evidence of severity and tractability. This intentional effort helped the network mitigate fragmenting pressures, develop consensus strategies, expand membership and influence attention toward the disease. From 2008 until the present, a series of significant accomplishments strengthened and expanded the network, while this revitalized network leveraged new opportunities to obtain new funding sources and see rapid gains in national immunization policies and implementation.

Table 2.

Childhood pneumonia network eras

| Era | Dates | Structure | Actors | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early work | Pre 1984 | Isolated individuals or clusters | Researchers, physicians | Basic research |

| ARI programs | 1984–1995 | First global network | WHO, national programs, researchers, physicians | Development of policy and guidance at all levels of care |

| IMCI begins | 1995–2003 | Reabsorbed into child health, with some scattered clusters remaining | Researchers, physicians | Basic research; calls for attention; IMCI primarily focused on facility level care |

| (Re)Emergence | 2003–2008 | Global network forms (or re-emerges) with clusters interacting | WHO, UNICEF, researchers and universities, GAVI initiatives, some NGOs | Development of a common global strategy; immunization policy campaigns; resumed focus on community-level care |

| Acceleration | 2008 to present | Growing number of less active members around core clusters | WHO, UNICEF, researchers and universities, GAVI initiatives, many more NGOs, national programs | Agreement on global strategy; rapid uptake of immunization policies; increased advocacy efforts |

Early work (Before 1984)

Before the 1980s, global attention to pneumonia was very limited, and primarily the domain of high income country scholarship and attention. ‘It was a very lonely place to be in the “70”s and “80”s’ (Interview 14). Researchers working within LMICs, or in clusters of poverty within wealthier nations, observed first-hand the ravages of pneumonia, often while also focusing on other diseases such as malaria, meningitis or diarrheal diseases (Interviews 10, 11 and 14). Physicians working in Papua New Guinea and other LMICs pioneered diagnosis and treatments for pneumonia in resource scarce contexts during the 1970s and 1980s (Shann et al. 1984; Interview 26; Campbell et al. 1989; Pio 2003), starting to develop early evidence to support claims of tractability. During this period, a community of scholars, policy-makers or advocates did not yet cohere into a network working on childhood pneumonia, but began establishing a shared identity enabling future network formation.

While working within LMICs, pediatricians witnessed similar levels of inattention across diseases. Peumonia, malaria, diarrheal diseases, tuberculosis and neonatal conditions harmed and killed children in these communities but at the time were subject to little global attention (Interviews 10, 11 and 14). In later decades, network formation and attention to these diseases would diverge, with malaria (Interviews 13 and 14) and TB (Quissell and Walt 2016) being relatively successful at garnering policy attention, newborn survival having some more recent success (Shiffman 2016) and diarrheal diseases and pneumonia lagging behind.

Early establishment of network ties between researchers and physicians may have been held back by the disease’s position in medical practice. Unlike other diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, the medical community focused on pneumonia is fragmented and not the target of a large specialty, limiting the pool of potential allies and network members. In part, this is due to the disease’s complicated nature, with multiple causal agents, risk factors and potential interventions. Childhood pneumonia is served by pediatricians and is primarily a focus in LMICs, resulting in an affected group easily labelled as innocent but without the power to substantially influence attention to the issue (Nathanson 2007). It is separate from the laboratory and clinical specialists focused upon adult and community-acquired pneumonia in high-income nations (Interviews 11 and 16). These issue characteristics left childhood pneumonia without a natural constituency for network membership or pre-existing basis for developing a shared identity. During this period, the researchers and physicians occupying this relatively isolated area of scholarship and care began to forge a shared identify around community-level treatment of pneumonia and its neglect by the broader medical community, but did not yet engage in the frequent interaction or structure development that would constitute network formation. Building of relationships and network structures may have required alternative means for encouraging collaboration, which arrived in the form of the WHO’s ARI Programme.

ARI era (1984–1995)

During the 1980s and early-1990s, the World Health Organization and national ministries oversaw programs dedicated to pneumonia efforts, generally called ARI programs. The WHO program began in response to calls for action on pneumonia from LMICs (Pio 1988). These programs ran from 1984 (Pio 1988) until 1995, when they were folded into programs for Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) along with similar programs for diarrheal diseases and vaccine preventable childhood illnesses (Campbell and Gove 1996; Winch et al. 2002; WHO 1995; Interview 16). In 1994, just before the switch away from pneumonia occurred, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (now ‘the Union’) added a subgroup for ARI and included pneumonia in its annual conference for the first time, with many of the presentations by WHO personnel (Interview 20). These venues enabled the emergence of a global childhood pneumonia network, albeit one primarily focused on community-level care.

Promising research emerged during this period, including initial estimates of mortality from the disease (Bulla and Hitze 1978; Leowski 1986; Garenne et al. 1992; see Table 3 for the history of pneumonia mortality estimates). Global standards for visual, rather than radiological, diagnosis of high respiratory rates and troubled breathing were established (Campbell et al. 1989; Falade et al. 1995; Shann et al. 1984). Other research provided guidance on case management of the disease (Khallaf and Pio 1997), primarily at the community level (Bang et al. 1990; Sazawal and Black 1992). During the mid-1980s, this guidance was updated several times per year, and tailored to three levels of health systems—the community, first level clinics and district hospitals (Interview 10). This research created evidence of severity and tractability sufficient to motivate those working on community case management (CCM) of pneumonia but did not yet influence broader audiences, as evidenced by the relatively lower citation counts of these early estimates (see Table 3). A highly cited examination of strategies to address child mortality failed to even reference pneumonia (Mosley 1984), suggesting that these early estimates had not yet influenced perceptions of child survival experts.

Table 3.

Pneumonia mortality estimates

| Source | Latest date used | Annual mortality, millions | Citations, Google Scholar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulla and Hitze (1978) | 1976 | 1.0 | 174 |

| Leowski (1986) without measles and pertussis | 1983 | 2.7 | 26 |

| WHO from Garenne et al. (1992) | 1991 | 3.6 | |

| Garenne et al. (1992) | 1991 | 2.2 | 236 |

| WHO (1995) | 1993 | 3.3 | |

| Williams et al. (2002) | 2000 | 1.9 | 634 |

| Black et al. (2003) | 2000 | 2.1 | 2241 |

| Rudan et al. (2008) | 2000 | 2.9 | 703 |

| Bryce et al. (2005) | 2003 | 2.0 | 1594 |

| Black et al. (2010) | 2008 | 1.6 | 1502 |

| Lozano et al. (2013) | 2010 | 0.8 | 2110 |

| Liu et al. (2012) | 2010 | 1.1 | 892 |

| Nair et al. (2013) | 2010 | 1.4 | 66 |

| Walker et al. (2013) | 2011 | 1.3 | 178 |

| Liu et al. (2015) | 2013 | 0.9 | 26 |

A series of WHO meetings in 1981 (WHO 1981; Interview 26), 1984 (WHO 1984; Interview 26), and 1988 (Interview 10) involved investigators from various community-level studies and led the WHO to find CCM effective. However, this research acknowledged the need to overcome policy barriers, such as opposition from paediatricians (Interview 4) and criticisms of findings being context-specific (Interview 3). Just as some respondents felt these efforts were starting to gain traction (Interviews 10 and 16), shifts in the global structure of child survival programs supplanted the ARI programs.

The initial network focused on childhood pneumonia consisted of physicians and WHO officials sharing an identity rooted in community-level care for the disease. This narrow specialist identity was demonstrated by the use of the technical term ‘acute respiratory infection’ rather than the more common pneumonia, a framing choice criticized by several respondents (Interviews 4, 5, 12, 14 and 15). Due to this narrow-shared identity and lack of member diversity, the network lacked sufficient relationships with potential collaborators and access to other information sources, leaving it relatively powerless in the face of a major shift in global child survival efforts, the start of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI).

IMCI era (1995–2003)

The consolidation of global child health programs into IMCI initial impacted pneumonia efforts and network formation negatively. A joint effort, three programs at UNICEF and eleven at the WHO participated in IMCI planning (Gove 1997). The pneumonia and diarrheal disease programs were subsidiary units to just one of these eleven WHO groups. Rather than the previously vertical programs against pneumonia and diarrhea, IMCI focused on horizontal programs covering the broad spectrum of childhood illnesses (Interviews 10 and 16). IMCI proponents cited the frequency of multiple diseases amongst very ill children as requiring a comprehensive approach (Campbell and Gove 1996; WHO 1995). As a result, IMCI was expected to benefit health systems by reducing overlaps and coordinating planning (Campbell and Gove 1996; Gove 1997). Despite these potential advantages, IMCI’s initial focus and activities hampered pneumonia efforts by deemphasizing the disease and community-level care. It also impeded network formation by replacing the venues for member interaction presented by the ARI Programme.

In pursuing systems able to handle coinfections and a range of childhood illnesses, earlier progress on pneumonia and community case management were overlooked. IMCI is criticized for ignoring or delaying community-level care (Interviews 10 and 24), which is supported by examination of its initial focus. Early implementation, guidance and performance indicators prioritized facility based care and ignored community-level care in favour of household behaviours (WHO 1995; Bryce and Victora 2005; Winch et al. 2005). Pneumonia was similarly overlooked with no initial indicators directly related to the disease (see Lambrechts et al. 1999 for list of indicators). Some countries, like Nepal and Chile, continued moving forward on community case management, (Interviews 10 and 26), but under explicit WHO pressure most switched from separate ARI and diarrhoea programs to the consolidated child health of IMCI (Interviews 16 and 20). Pneumonia and CCM experts felt excluded from the new IMCI structure that overlooked evidence of CCM effectiveness (Interview 10) and failed to even mention pneumonia in annual reports (Interview 16).

Formal evaluations support criticisms of IMCI and pneumonia. They found evidence of less progress than other diseases, little or no movement on community care or prevention, and continued or increased equity gaps in access to care. Multicountry assessment visits found little or no implementation at the community or system levels (Bryce and Victora 2005). Findings from Brazil indicated failures to reach poorer communities (Victora et al. 2006). Evidence from Bangladesh saw the percentage of childhood deaths from pneumonia rise in IMCI districts, despite overall declines in mortality across both treatment and control communities (Arifeen et al. 2009). Even where declines in pneumonia mortality were observed, evaluations could not attribute IMCI with having an impact (Arifeen et al. 2009).

The WHO’s shift away from ARI specific efforts, and inattention by UNICEF to pneumonia, influenced donors and, in turn, potential researchers (Interview 20). During the IMCI era, actors working on pneumonia primarily remained within intervention-specific clusters or shifted to a broader child survival focus, rather than consolidating into a single childhood pneumonia network. Groups of researchers focused on vaccines, community case management, diagnosis, household air pollution and other aspects of pneumonia generally remained within their intervention cluster and competed for funding and attention (Interviews 4, 14, 15 and 22). Individuals and groups focused on pneumonia continued to perform research and raise calls for greater attention (Khallaf and Pio 1997; Mulholland 1999; Mulholland et al. 1997; Mulholland et al. 1999; Rasmussen, Pio and Enarson 2000; Interview 20). This frustration with the lack of progress contributed to development of a shared identity and eventual network formation.

None of this evidence repudiates IMCI’s broader impacts on child survival, or even its potential to have addressed pneumonia in its early years. Instead, it reveals the importance of timing and the relationship between the political environment and characteristics of individual issues and the network. IMCI needed to juggle the disease and intervention priorities of fourteen different programs. Meanwhile, pneumonia’s network centred on a narrow shared identity, framed its work in very scientific (ARI) terminology and relied on very early and limited evidence of severity and tractability. Had pneumococcal and Hib vaccines been as well developed and evidenced as measles vaccines at that point, pneumonia almost certainly would have factored more prominently in initial guidance and metrics. Similarly, if CCM evidence were more mature or the network incorporated a broader membership, pneumonia experts may have exerted greater influence in the design of IMCI. Given that IMCI continues to be the structure for WHO and UNICEF child survival efforts, later successes in pneumonia network formation and impact suggest that IMCI could have been an opportunity, rather than barrier, to progress on the issue.

Evidence of pneumonia’s deadly toll, developed by the Child Health Epidemiology Research Group (CHERG), and evidence for tractability in the form of vaccine development figured prominently in a network of actors breaking away from broader child survival efforts to reinvigorate—or perhaps resuscitate—pneumonia network formation. Other critical developments at the turn of the millennium, in the form of actor decisions and political opportunities, also served as triggering factors for this process.

Network (Re)Emergence (2003–2008)

In the early 2000s, a series of events created the opportunity for a pneumonia network to reemerge and strengthen. Parts of the childhood pneumonia community operated as a single network during the ARI era before losing traction under IMCI, but the composition of network emerging later in the 2000s differed substantially. As such, this process could be viewed as a previously existing network re-emerging and expanding, or as a new comprehensive network for childhood pneumonia emerging and drawing upon some intervention communities, or clusters, with pre-existing relationships and shared identities.

New research, much of it conducted by eventual network members, provided necessary support for efforts to form a network, attract attention, craft and enact policies. Evidence on pneumonia’s severity from CHERG (Williams et al. 2002; Black et al. 2003; Rudan et al. 2004) labelled pneumonia as the leading killer of children, revealed slow progress on reducing mortality (Bryce et al. 2003; Bryce et al. 2005), were widely read and cited (see Table 3 above), and built agreement about severity amongst major actors (Interview 22). Continuation and dissemination of progress on vaccine development for both pneumococcus (Mulholland et al. 1999; Black et al. 2000; Cutts et al. 2005) and Hib (Mulholland et al. 1997; Miller and McCann 2000; Adegbola et al. 2005) prior to and during this period demonstrated the efficacy and safety of scaling up immunizations. New research on community case management (Pio 2003; Sazawal and Black 2003; Winch et al. 2005) supported the earlier findings of the ARI era. These research advances, the product of long-running efforts by small cadres of dedicated scientists, introduced new evidence of severity and tractability and encouraged renewed attention to the disease. Analysis of continued research needs prioritized implementation studies over further evidence of efficacy or development of new interventions, and cited the need for existing evidence to influence future funding (Rudan et al. 2007).

The external environment changed substantially during this period and created opportunities for network emergence and impact. Millennium Development Goal 4 placed a global focus upon lowering childhood mortality rates and implicitly required pneumonia progress to succeed (Bryce et al. 2005). This norm created a political opportunity for pneumonia, but at a time when the network was still emerging. Despite MDG-4 figuring prominently in items documenting network emergence (UNICEF and WHO 2006; WHO et al. 2008; WHO et al. 2009), interviewees attributed little emphasis to them as a force for change. Unsurprisingly, groups of isolated actors yet to forge a shared identity, history of social ties and network structures were poorly positioned to take advantage of this political opportunity.

The re-emergence of WHO and UNICEF in childhood pneumonia leadership roles, along with the entrance of major funders into the issue, created opportunities for network formation, especially when combined with conscious efforts to build a shared identity incorporating a broad spectrum of those involved in pneumonia efforts. Within WHO, pneumonia efforts were divided between two separate departments that included attention to child health and immunizations, respectively, to the possible detriment of efforts on pneumonia. Cooperation and coordination just between the two departments on the issues is influenced substantially by the leaders and priorities of each, and improved during the early 2000s (Interview 12).

IMCI captured UNICEF’s attention during the 1990s (Interviews 9 and 20), but the organization re-emerged as a global leader in pneumonia network emergence. This reengagement was influenced by new data on child mortality (Interview 19). UNICEF and WHO jointly published the 2006 report ‘Forgotten Killer of Children’ to share this evidence and garner attention for the issue. The crafting of this document drew on expertise from pneumonia network members, including key actors in the re-emergent network. UNICEF pushed heavily for a renewed focus on community case management (Interview 19), joining with WHO to release a joint statement (UNICEF and WHO 2004) and setting the stage for greater involvement by that community.

For the first time, substantial funding began to appear from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. GAVI began shifting attention toward pneumococcus in 2003 and Hib in 2005. It established PneumoADIP (Interviews 4, 22) and the Hib Initiative (Interview 8) to encourage adoption of these vaccines by national immunization programs. These initiatives drew on organizations—the Center for Disease Prevention (CDC), Johns Hopkins and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)—and individuals that joined the remerging network. The Gates Foundation began providing resources for pneumonia efforts around the same time, as a major contributor to GAVI and funder of other pneumonia specific grants, primarily related to immunizations (Interviews 4 and 22). Accompanying—and influenced by—new funding and vaccine initiatives, were changes in global policy, including the 2006 revision of WHO’s position recommending use of the Hib vaccine (Hajjeh et al. 2010). These new funding streams provided windows of opportunities for the actors already involved in pneumonia efforts to strengthen their activities and for others to shift more of their focus to pneumonia.

During this period, the actors focused on diverse pieces of the pneumonia puzzle began to cohere and operate as a network. Long-running informal discussions and meetings of those involved in pneumonia revealed frustration with progress and led to public calls for change. Meetings, such as the 2006 Biennial International Symposia on Pneumococcus and Pneumococcal Diseases (ISPPD-5) in Alice Springs (WHO et al. 2006; Interview 4; Cripps et al. 2007) and other intermittent meetings like Stockholm in 2002 and Scottsdale, AZ in 2003 (Interview 11), brought potential network members together. Still, it was purposive network formation efforts, primarily credited to leaders from the WHO, that truly brought members together (Interviews 1, 2, 3 and 22).

Under the guidance of the WHO and UNICEF (Interviews 1, 19 and 22), informal consultations on the development of a Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Treatment of Pneumonia (GAPP) were conducted (WHO et al. 2008; WHO et al. 2009) and served as focusing events for building shared identity and the network. PneumoADIP and the Hib Initiative also served prominent roles, especially in building and distributing evidence of tractability. These meetings sought to build an internal consensus, end internecine squabbling—particularly competition over resources and failure to coordinate—and identify target activities and outcomes for the community as a whole (Interviews 4, 12 and 22). Participants in these consultations included a range of experts across different intervention clusters, including key leaders in the emerging network. Organizers from the WHO and UNICEF identified these participants through a snowball selection process, consciously expanding the group in the second year to draw more from within national programs (WHO et al. 2009; Interviews 12 and 19). These various conferences and consultations served to begin building a shared identity amongst potential network members. The development of this shared identity, initial network structures and evidence on severity and tractability, all products of long-running efforts against pneumonia, set the stage for the most recent era in pneumonia efforts, one of accelerating efforts that would see substantial increases in attention, funding, national policies and implementation.

Acceleration of network efforts (2008-present)

From 2008 through 2014, the now emerged and growing network saw rapid progress on some measures of attention to pneumonia. Both network member actions and changes in the issue environment, particularly vaccine technology and funding, influenced these accelerating results. Network members began global and national level advocacy efforts with a consensus strategy and formal coalition. Global consensus on a comprehensive set of interventions emerged, with some substantial increases in the uptake of national-level policies reflecting this guidance. Funding, policies, and implementation for other interventions lagged behind the rapid advances for pneumococcal and Hib vaccines, but this period saw tangible outcomes unobserved in the prior decades. The acceleration and spread of these advances reveal interrelations between actors influencing attention, funding, policy adoption and implementation, and is consistent with the arenas model of attention (Hilgartner and Bosk 1985). At the core of the network efforts that helped to achieve these advances lay a shared identity that broadly welcomed all aspects of pneumonia prevention and treatment.

The informal consultations and resulting Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Treatment of Pneumonia (GAPP) served an important role by identifying a comprehensive approach to childhood pneumonia mitigation that all key parties accepted (WHO et al. 2008, 2009). For the first time, the various clusters—primarily immunizations, facility-based management, community case management, household air pollution and nutrition—could point to a single plan the included their focal interventions. The GAPP (WHO and UNICEF 2008) did not end all internal conflicts around the pursuit of intervention specific funding and policies (Interviews 4, 14, 15 and 22), but helped network members focus more on areas of agreement (Interviews 4, 12 and 19).

Building directly on the global action plan’s informal consultations, efforts to publish more research and gain attention from global policy-makers and scholars saw some success. Researchers, including individuals in the network, continued work on various aspects of the disease, related risk factors and potential interventions. Most notably, the Bulletin of the World Health Organization published a special issue on pneumonia (including Enarson et al. 2008; Jeena 2008; Madhi et al. 2008; Marsh et al. 2008; Rudan et al. 2008; amongst others) that network members use to garner attention, influence national-level policy-makers and educate health providers (Interview 2). Network members continued this collaboration by jointly identifying research gaps to spur further advances and holding a donor conference to share the evidence and gaps with potential funders (Rudan et al. 2011).

Advocacy and policy efforts expanded during this period. These included regional workshops, informal interactions, small grant programs, and the establishment of a day dedicated to pneumonia and a global coalition. A central goal developed by participants in the GAPP consultations was to pursue a World Health Assembly resolution (WHO et al. 2008), which passed in 2010. The regional workshops and small grant programs by WHO and IVAC reach paediatricians, finance ministers and national level advocates (Interviews 4, 6 and 24). Other network members ran similar programs within individual countries (Interviews 1, 20, 24). Respondents credit these programs and the wider involvement of national level decision makers as essential for achieving policy diffusion (Interviews 1, 4, 6, 20 and 24). World Pneumonia Day, first held on November, 2009, grew out of efforts by members of the network and a push from an outside philanthropist (Interviews 1, 4, 12 and 13). Though criticized by some as mostly limited to the USA (Interviews 14, 17 and 22) and of limited impact (Interview 21), the Day is praised by others for focusing network members’ efforts (Interviews 1, 12). Its creation is also credited for providing impetus for a faster, more widespread release of the GAPP (Interview 4). Members of the network also started the Global Coalition Against Child Pneumonia (GCACP). Since the early flurry of action around World Pneumonia Day in 2009, the number of events and participating countries steadily declined, in favour of a focus on virtual activity. Meanwhile membership in GCACP continually rose and the third day saw the highest level of media attention (see Table 4, below), including editorials by key decision-makers outside the network (Calvin 2011; Gates 2011; NIH 2011). No reports have been released on the 2013 and 2014 WPDs, though activities continued.

Table 4.

World pneumonia day growth

| Members | Events | Countries | Media articles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 84 | 167 | 36 | 330 |

| 2010 | 138 | 78 | 28 | 267 |

| 2011 | 143 | 62 | 29 | 494 |

| 2012 | 147 | 30 | 10+ | 362 |

Data sources: IVAC (2010, 2011b, 2012, 2013).

Prior to this recent advocacy and the evidence of severity from CHERG, many global health funders, along with the general public, held mistaken views of pneumonia’s impact. One respondent discussed observations from a series of interviews with global health funders in 2004 and 2005 that demonstrated flawed knowledge of childhood mortality causes: ‘Zero of thirty could identify pneumonia as the leading killer of children. These are people who program billions in global health spending. Zero of thirty. And then when we asked them, ‘what do you think kills the most children?’, they said, ‘AIDS, TB and Malaria.’ ‘Wrong, wrong and number three’ (Interview 4). This lack of awareness amongst global leaders and similar unfamiliarity amongst the general public is criticized as partially a failure in messaging (Interviews 4 and 12). Network members sought to improve communications by sharing the research on pneumonia’s mortality burden and framing the disease as the leading killer of children.

Much of the network composition and leadership drew on individuals and organizations focused on immunizations or community case management. Individuals or groups focused on other interventions or related issues—including adult pneumonia, diagnostics, facility-based case management, HIV positive children, household air pollution and nutrition—participate in the network, but generally are seen as less central to the network. Recently, some organizations in these other intervention clusters, such as the UN Foundation’s Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves (Interviews 12 and 19), have strategically integrated themselves into network activities and leadership. Members of other communities, particularly nutrition (Interview 5), view their mandate as broader than a single disease and do not consider themselves focused on pneumonia, even when they have participated in efforts like the GAPP consultations. The limited involvement of other groups might relate more to their alternatives than any deliberate exclusion by the network’s founders (Interviews 12, 19 and 21), with facility-based management well-served by IMCI and HIV positive children with pneumonia having far greater resources available in HIV/AIDS networks. Network membership is primarily composed of researchers and international bureaucrats, with some advocates, care providers and national policy-makers also involved. Industry involvement is intentionally limited due to concerns about lack of goal alignment (Interview 6), though some members desire increased engagement to address drug stock-outs and limited diagnostic tools (IVAC 2011a; Interview 19).

The acceleration of efforts by the pneumonia network has not changed its structure or leadership much, even with addition of many new actors through the GCACP. Concentration of efforts and attention is generally within intervention specific clusters, with the community case management and vaccine groups being most involved in the network. WHO and UNICEF have taken less active leadership roles than when re-establishing the network, but remain involved (Interviews 1, 12). Unlike formalized networks for other issues, the informal pneumonia network’s secretariat roles are widely distributed, including to IVAC (Interviews 1, 4, 6, 14 and 22), USAID’s Maternal and Child Integrated Program (MCHIP) (Interviews 1, 3), the Community Case Management Task Force (Interview 1) and the Sabin Institute’s Pneumococcal Awareness Community of Experts (PACE) (Interviews 4, 6 and 18). Other leadership emerges spontaneously and informally, and is aligned with the network’s shared identity that refuses to favour a single intervention.

The pneumonia network may also have entered a new era in 2013 by working more closely with the community/network addressing diarrheal diseases. This partnership included a joint global action plan (WHO and UNICEF 2013) and a Lancet series on the two issues (Bhutta et al. 2013; Chopra et al. 2013; Gill et al. 2013; Walker et al. 2013). Though no respondents mentioned efforts to coordinate across issues when interviewed in 2011, half of them made unprompted comparisons to diarrheal diseases, discussed a history of involvement with both diseases, or identified the two diseases as being in similar circumstances (Interviews 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 19, 20, 21 and 22). Although this partnership between issues is too early along to diagnose whether the networks have merged, it fits with the re-emerged pneumonia network’s focus on a shared identity around the leading killer(s) of children being neglected, instead of prioritizing individual interventions.

Acceleration and limits of progress on impacts (2008–present)

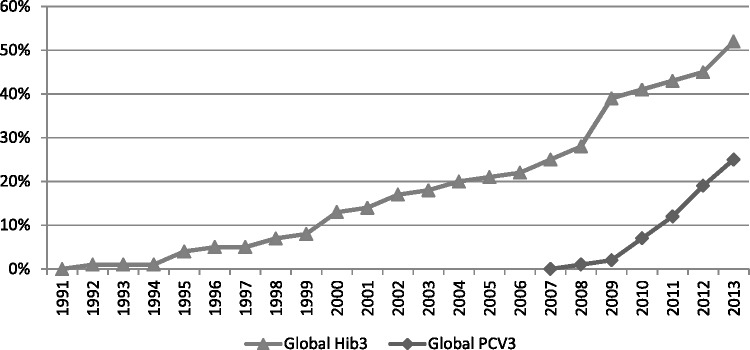

Despite a decade of substantial and rapid progress on pneumonia efforts, particularly for immunizations, network members continued to call attention to significant limitations that remain. As one respondent noted, ‘[pneumonia funding and attention] is pretty pathetic really on a global scale compared with the HIV or the malaria communities’ (Interview 14). Examination of childhood pneumonia funding for research (Rudan et al. 2011) and implementation (IMHE 2014) reveal continued disparities when compared to the disease’s mortality burden. Pneumococcal and Hib vaccines have received substantial investments, primarily from GAVI, and receive the majority of the disease’s research and development funding. A 2009 $1.5 billion advance market commitment for pneumococcal vaccines has helped this progress and provided incentives for vaccine research (Cernuschi et al. 2011). The selection of this vaccine from amongst six alternatives drew not from direct involvement or ties to network members, none of whom served on its Disease Expert Committee, but from evidence of severity and tractability that led this committee to view it as having the greatest potential for speedy impact (AMC 2009). Nearly all GAVI eligible countries have enacted policies to incorporate pneumococcal and Hib vaccines in their immunization programs (Interviews 4, 6, 8, 12 and 18). Though vaccine coverage is rapidly progressing, Hib and pneumococcal vaccines still only reach half and a quarter of children, respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative estimated global vaccine coverage rates. Data source: WHO Global Immunization Data, www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/en/.

The true barrier remaining to immunization campaigns is reaching children in high population nations like India and Nigeria (Interviews 4, 24), especially as the largest portion of childhood pneumonia mortality originates in these countries (Rudan et al. 2008). Network members such as IVAC have programs in place specifically focused on these critical countries (Interview 25).

The other interventions lag further behind. Network members still see the need for further evidence, either context specific or of effective interventions, for community case management, household air pollution and nutrition (Rudan et al. 2011; Interviews 1, 15). Policies and programs for community case management are expanding rapidly, at least relative to the IMCI era, but are heavily reliant on donors (Interviews 1 and 10). Funding for these interventions and more general support of necessary health systems components, is badly needed, and mentioned by almost every single respondent. Many respondents felt the lack of charismatic, public figures as advocates for pneumonia held the network back from significantly increasing attention and support. Public, media (Hudacek et al. 2011) and policy-maker attention still remains limited for pneumonia, at least relative to other global health issues.

Progress on the most critical metric, the number of children dying from the disease, demonstrated a different and consistent pattern. Estimated annual child mortality from pneumonia declined drastically and mostly consistently over the period examined in this study, from almost three million in the 1980s (Leowski 1986) to under a million in 2013 (Liu et al. 2015) (refer back to Table 3 to see change in mortality estimates over time). This decline began during periods of relative quiet by the network and continued as the network emerged and began to influence policies and attention.

Discussion

The childhood pneumonia network took over two decades to emerge following initial efforts to craft a shared identity and develop network ties. Another five years passed before rapidly accelerating gains in attention to the issue and adoption of policies. Network emergence stagnated until deliberate efforts to craft a broad shared identity attracted membership from across the spectrum of pneumonia related interventions. Network members lacked access to external opportunities until the network emerged and had sufficient evidence on severity and tractability sufficient to influence outside decision-makers. Major shifts in attention to the issue and health impacts indirectly drew on network and member activities, particularly in sharing evidence and providing venues for public attention, but occurred outside the network’s sphere of immediate influence.

The context and evolution of efforts against childhood pneumonia generally aligned with the GHAPP’s theoretic framework. Childhood pneumonia advocates competed for attention from various arenas (Hilgartner and Bosk 1995), both against other health issues and amongst different intervention communities. Competition included development of evidence on severity and tractability (Adler and Haas 1992), crafting a shared identity (Staggenborg 2002), favoured intervention strategies (Kingdon 1984) and framing of the issue (Benford and Snow 2000). When substantial attention and progress occurred, it did so rapidly, punctuating a previously quiet equilibrium (Baumgartner and Jones 1993). The case reveals three specific findings of relevance to other issues: (1) tradeoffs between narrow and broad shared identities, (2) network structures and evidence as necessary preconditions to access opportunities and (3) networks serving as secondary, indirect influences on attention and policy, rather than lead actors.

Efforts to form a pneumonia network began in a context with a fragmented potential membership and lack of a pre-existing constituency or shared identity. As a result, forming a narrow network around a single intervention could occur far easier, but brought significant limitations. The ARI era network incorporated a narrow shared identity and network composition, in a context of fragmented potential network members. The narrow identity and composition of this era, centred on community case management, lacked the weak ties to other interests and actors that serve as sources of information and power over decision-making (Granovetter 1973; Staggenborg 2002). When broader child survival efforts shifted toward the horizontal IMCI, pneumonia and community case management failed to appear in early guidance or targets, indicating a lack of voice from this early pneumonia network in IMCI’s formation. The early state of research on pneumonia mortality and interventions may also have left initial network members without sufficient evidence of severity and tractability to persuade others in the broader child survival community. Given that IMCI continued to be the dominant approach to childhood diseases during the pneumonia network’s emergence and recent successes, the integrated approach and structure could have better aligned with the fledgling network if its composition and evidence base had differed.

In reforming the network, a broader shared identity allowed for the inclusion of all intervention communities, which since 2013 may have broadened to include diarrheal diseases. In this broadening, subgroups or clusters within the network remain relatively independent, which can be challenging for collective action. The expanded network now includes a broader spectrum of participants, but at a cost of individual involvement and frequency of communication. This identity is not fixed, and will likely undergo revisions in response to the diarrheal disease partnership and continued mortality declines.

For other health issues, identifying the core elements of their shared identity and the resulting member composition becomes an essential first task. Overly narrow identities can leave network members isolated from larger efforts, sources of information and potential allies. Overly broad identities can result in lessened urgency, unaddressed constituency concerns, unreconciled internal conflicts, ineffective framing strategies and reduced incentives for participation. These tradeoffs are critical for issues that, like pneumonia, incorporate a potential membership that is fragmented by different interventions and expert communities.

The pneumonia case also reveals a mutually constitutive relationship between network characteristics and those of its issue and environment. Issue characteristics can influence decisions about composition, identity and framing strategies, but networks serve as venues to shift perceptions of severity and tractability. In this case, scientific evidence for severity and tractability was a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for network formation and attention to the issue. Similarly, the presence of shared identity, ties and relationships served as necessary conditions for the network to seize opportunities presented by changes in funding, norms and potential allies. Five different political opportunities emerged during the pneumonia network’s different eras, providing potential opportunities for major changes (Kingdon 1984; Baumgartner and Jones 1993). When the WHO established its ARI Programme, the ties between community case management experts allowed for them to leverage this opportunity to make early progress creating national program creation and developing CCM guidance. The shift to IMCI returned focus to facility-level care, but also provided a potential opportunity to include pneumonia in initial guidance, attract attention and increase funding. During most of IMCI’s first decade, pneumonia and community case management did not benefit from this opportunity. The weakening or dissolution of the pneumonia network following the shift to IMCI also left actors without the shared identity or ties (Staggenborg 2002) necessary to quickly activate into a network (Agranoff and McGuire 2001). This slowed response to two major shifts in the global health landscape: the creation of the Millennium development goals and the establishment of new funding entities like the Gates Foundation, GAVI and the Global Fund. Gates Foundation and GAVI funding became core elements of pneumonia efforts, but only after intentional efforts to develop a network and share evidence on severity and tractability. In contrast, the network’s existing structures, relationship and identity allowed its members to seize the opportunity afforded by the advance market commitment to further accelerate vaccine policy and implementation progress. The network’s differential abilities to access these opportunities supports the importance of building and maintaining shared identity, interpersonal ties and network structures even in environments of inattention and quiet. This background work builds collective perceptions of hope and the potential for action (Staggenbrog 2002) that enable networks to access new opportunities. The development and framing of scientific evidence (Adler and Haas 1992; Benford and Snow 2000) sufficient to influence key outside decision-makers is also essential for issues and networks to benefit from these emerging opportunities.

This case begins to resolve the critical question: to what extent and under what circumstances do networks matter? As Table 5 (next page) illustrates members of the childhood pneumonia network primarily served supporting roles in achieving progress on the issue. They developed much, but not all, of the research leading to broader perceptions of severity and tractability, and intentionally sought to influence global and national leaders to adopt and implement policies. Most of the activities directly under the control of network members served as means to indirectly influence key decision-makers, rather than exerting clear influence on attention, policies or interventions. Major changes, including CHERG’s evidence, the GAVI initiatives, WHA resolution and funding commitments, were led by actors outside the network. Where network members participate, they did so in supporting roles or through the evidence of severity and tractability they developed and shared. In some cases, outside actors involved in these changes later became integral members of the network (including CHERG, the GAVI initiatives and UNICEF). Throughout the entire period that the network sought to form and then accelerate efforts against pneumonia global mortality estimates declined. It is difficult to attribute much of this decline to network activities, except for the last couple of years where rapidly growing immunization coverage likely started to impact mortality.

Table 5.

Summary of network involvement

| Network iteration |

Key activities sorted by network involvement |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era | Structure | Key actors | Direct/major role | Indirect/minor role | Minimal/no role |

| Pre 1984 | Not yet a network | Individual researchers and physicians | Early research on CCM, diagnostics, and severity | Research on other interventions | |

| 1984–1995 | Small, narrow emerging network | WHO, CCM researchers, some national ARI programs | Collaboration on CCM research; CCM guidance | Formation of WHO (ARI) and national programs | Mortality decline |

| 1995–2003 | Isolated intervention specific clusters | Individual researchers on multiple interventions | Some collaboration on intervention research | Severity research (CHERG) | Formation and design of IMCI; MDG-4; Initial GAVI priorities; Mortality decline |

| 2003–2008 | Larger, broad, mostly informal emerging network | WHO, UNICEF, GAVI Initiatives (pneumoADIP, Hib Initiative), individual researchers and universities, some NGOs | Collaboration and coordination on research; sharing research findings; BWHO special issue; GAPP | Formation of GAVI initiatives; UNICEF reinvolvement; WHO vaccine guidance | Mortality decline |

| 2008–present | Expanding, broad, partially formalizing network with varying level of member activity | WHO, UNICEF, GAVI Initiatives (IVAC), more researchers and universities, more NGOs, some national programs | Widespread collaboration and coordination on research; Sharing research findings; World Pneumonia Day; GCAP; Small grants program/National advocacy; Progress reports; GAPPD | Funding increases (Advance Market Commitment, GAVI, Gates Foundation); National immunization policies; WHA resolution; Mortality decline? | Mortality decline? |

Other articles in this special issue address this question further, but room remains for future research to continue examining the importance and impact of global health networks. Exploration of the consistent and substantial mortality declines, by researchers more conversant with the underlying data, assumptions and methodology, could better attribute influence of various factors, to include activities of network members, on the decline, and thus provide a clearer idea of how networks contribute to health outcomes. Similarly, future research can expand our knowledge of the interactions between shared identities, network elements, issue characteristics and the environment. Contrasts between issues can identify when these dynamics become more important and further develop an understanding of how networks form and influence various measures of advocacy, policy, implementation and outcomes.

The example of childhood pneumonia’s network provides an example, some hope and guidance for neglected issues. Even in contexts challenging to network emergence and impact, it is possible to undertake strategies to build a broad shared identity to attract a membership and then indirectly influence key decisions. Global health networks do not need to be the driving force for funding decisions, public and elite attention and health impacts in order to see gains related to their issues. Engaging in the lengthy and deliberate processes of building network ties, crafting and sharing evidence, and collaborating on strategies and advocacy can be grounds for major changes, even if the credit more readily accrues to others.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation [OPPGH4831]. I am grateful to the Foundation and to all the individuals who agreed to be interviewed for this study. I also wish to acknowledge those who provided feedback on drafts of this article, especially Jeremy Shiffman, Asha George, Kelley Lee, multiple interviewees, my other GHAPP colleagues and two anonymous reviewers.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- Adegbola R, Secka O, Lahai G, Lloyd-Evans N. Elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease from The Gambia after the introduction of routine immunisation with a Hib conjugate vaccine: a prospective study. The Lancet. 2005;366:144–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66788-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler E, Haas PM. Conclusion: epistemic communities, world order, and the creation of a reflective research program. International organization. 1992;46:367–90. [Google Scholar]

- Agranoff R, McGuire M. Big questions in public network management research. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2001;11:295–326. [Google Scholar]

- Advance Market Commitments for Vaccines (AMC) Consultation and Advisory Process. Geneva: GAVI; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arifeen SE, Hoque D, Akter T, et al. Effect of the integrated management of childhood illness strategy on childhood mortality and nutrition in a rural area in Bangladesh: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet. 2009;374:393–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60828-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang A, Bang R, Tale O, et al. Reduction in pneumonia mortality and total childhood mortality by means of community-based intervention trial in Gadchiroli, India. The Lancet. 1990;336:201–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91733-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Sadruddin S, Khan A, et al. Community case management of severe pneumonia with oral amoxicillin in children aged 2–59 months in Haripur district, Pakistan: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet. 2011;378:1796–803. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61140-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates N, Herrington J. Advocacy for malaria prevention, control, and research in the twenty-first century. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;77:314–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner Frank R, Jones Bryan D. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Benford RD, Snow DA. Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:611. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Walker N, et al. Interventions to address deaths from childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea equitably: what works and at what cost? The Lancet. 2013;381:1417–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2010;375:1969–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? The Lancet. 2003;361:2226–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, et al. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2000;19:187–95. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce J, Victora CG. Ten methodological lessons from the multi-country evaluation of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness. Health Policy and Planning. 2005;20:i94–i105. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce J, el Arifeen S, Pariyo G, et al. Reducing child mortality: can public health deliver? The Lancet. 2003;362:159–64. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13870-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black R. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. The Lancet. 2005;365:1147–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulla A, Hitze K. Acute respiratory infections: a review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1978;56:481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvin K. Pneumonia: One Disease, Two Solutions. Huffington Post. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell H, Gove S. Integrated management of childhood infections and malnutrition: a global initiative. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1996;75:468. doi: 10.1136/adc.75.6.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell H, Lamont A, O’Neill K, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for identification of severe acute lower respiratory tract infections in children. The Lancet. 1989;333:297–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield L, de Onis M, Blossner M, Black R. Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;80:193. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernuschi T, Furrer E, Schwalbe N, Jones A, Berndt ER, McAdams S. Advance market commitment for pneumococcal vaccines: putting theory into practice. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011;89:913–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.087700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- César J, Victora C, Barros F, Santos I, Flores J. Impact of breast feeding on admission for pneumonia during postneonatal period in Brazil: nested case-control study. BMJ. 1999;318:1316. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7194.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian T, Mulholland EK, Carlin JB, et al. Standardized interpretation of paediatric chest radiographs for the diagnosis of pneumonia in epidemiological studies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005;83:353–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra M, Mason E, Borrazzo J, et al. Ending of preventable deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea: an achievable goal. The Lancet. 2013;381:1499–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps A, Leach A, Lehmann D, Benger N. Fifth International Symposium on Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases, Alice Springs, Central Australia, 2–6 April 2006. Vaccine. 2007;25:2361–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutts F, Zaman S, Enwere G, et al. Efficacy of nine-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease in The Gambia: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2005;365:1139–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enarson P, La Vincente S, Gie R, Maganga E, Chokani C. Implementation of an oxygen concentrator system in district hospital paediatric wards throughout Malawi. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86:344–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.048017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falade A, Tschäppeler H, Greenwood BM, Mulholland EK. Use of simple clinical signs to predict pneumonia in young Gambian children: the influence of malnutrition. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1995;73:299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedson DS, Anthony J, Scott G. The burden of pneumococcal disease among adults in developed and developing countries: what is and is not known. Vaccine. 1999;17:S11–S18. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnemore M, Sikkink K. International norm dynamics and political change. International organization. 1998;52:887–917. [Google Scholar]