Abstract

Objective Numerous articles have reported on the development of patient portals, including development problems and solutions. We review these articles to inform future patient portal development efforts and to provide a summary of the evidence base that can guide future research.

Materials and Methods We performed a systematic review of relevant literature to answer 5 questions: (1) What categories of problems related to patient portal development have been defined? (2) What causal factors have been identified by problem analysis and diagnosis? (3) What solutions have been proposed to ameliorate these causal factors? (4) Which proposed solutions have been implemented and in which organizational contexts? (5) Have implemented solutions been evaluated and what learning has been generated? Through searches on PubMed, ScienceDirect and LISTA, we included 109 articles.

Results We identified 5 main problem categories: achieving patient engagement, provider engagement, appropriate data governance, security and interoperability, and a sustainable business model. Further, we identified key factors contributing to these problems as well as solutions proposed to ameliorate them. While about half (45) of the 109 articles proposed solutions, fewer than half of these solutions (18) were implemented, and even fewer (5) were evaluated to generate learning about their effects.

Discussion Few studies systematically report on the patient portal development processes. As a result, the review does not provide an evidence base for portal development.

Conclusion Our findings support a set of recommendations for advancement of the evidence base: future research should build on existing evidence, draw on principles from design sciences conveyed in the problem-solving cycle, and seek to produce evidence within various different organizational contexts.

Keywords: patient portals, personal health records, systematic review, design and development, design sciences

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

A patient portal is a secure website through which patients can access personal health information and typically make use of several communication, self-management, and administrative functionalities.1 Although patient portals may differ across organizations, most include provisions to capture personal health information, provide linkages to convenience tools such as online appointment scheduling, and communication tools such as secure messaging with health service providers.2 Patient portals have been found to improve patient health and organizational performance as evidenced by better disease management, patient satisfaction, and enhanced administrative efficiency.3–7 Patient portals have been introduced in different types of organizational settings, including independent hospitals and physician practices, networks of practices, and larger integrated delivery systems.8 Up until recently, most patient portals were implemented and used within integrated care delivery systems that have the structure and resources to support internal development and maintenance as well as continuing implementation and deployment efforts.9 However, now, in response to the Meaningful Use program and similar national policy efforts to advance the use of health information technology, patient portals are increasingly being implemented in a variety of health care delivery contexts, including accountable care organizations and multispecialty provider practices.10,11

A rapidly growing body of scientific literature addresses the development of patient portals as well as the associated problems regarding, for instance, implementing required hardware and software; establishing portal content and capabilities; and achieving physician commitment and patient engagement, interoperability across providers, regulatory compliance, and financial sustainability in a variety of contexts.12,13 In addition to addressing these patient portal development problems, some studies have identified, implemented, and evaluated possible solutions. Due to an increasing interest in portals in various health care delivery contexts, the time is now ripe to systematically review the literature on these problems and solutions. Not only can such a review inform the development of new patient portals, it can also provide an account of the evidence base that can guide future research efforts.

OBJECTIVE

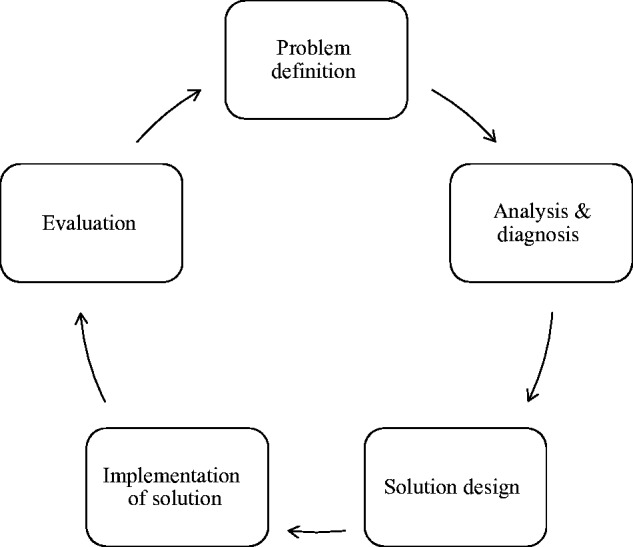

As we aim to systematically address the problems encountered in patient portal development, we organize our review using the problem-solving cycle depicted in figure 1. The problem-solving cycle forms a core model in design sciences (as well as in related disciplines such as systems/human factors engineering).14–16 Rather than a single-pass solution design process, problem-solving in the various interorganizational contexts of many patient portals—with their political and cultural complexities—typically requires multiple iterations of the cycle to successfully develop a patient portal. Such a cyclic improvement approach is referred to as a development approach,16 motivating our use of the term “patient portal development.” The problem-solving cycle explicitly facilitates identification of solutions aimed at ameliorating the problems encountered.

Figure 1:

The problem-solving cycle. Adapted from the model of Van Aken et al (2012).

Following the “steps” of the problem-solving cycle, we formulated 5 research questions to guide the review of scientific literature:

What categories of problems related to patient portal development have been defined?

What causal factors have been identified by problem analysis and diagnosis?

What solutions have been proposed to ameliorate these causal factors?

Which proposed solutions have been implemented and in which organizational contexts?

Have implemented solutions been evaluated and what learning has been generated?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our aim with this review was to systematically identify and describe main development problems and solutions. Since only the last of our research questions addresses the evaluation of effects through empirical research, we have not followed a review protocol to systematically review empirical evidence. Instead, we adapted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses checklist17 to assist us in answering the 5 research questions. The checklist items (12–16,19–24) regarding the evaluation of effects do not apply to our research questions. We do, however, address the quality of the studies and evidence obtained from the evaluation of solutions to problems (research question 5) in the discussion. For an overview of the effects of patient portals, we refer to several systematic reviews.3–7

Search process

We searched PubMed, ScienceDirect, and LISTA in January 2015 using a combination of queries capturing articles about “patient portals” and “electronic personal health records.” We included peer-reviewed articles written in the English language and published in the last 10 years. Table 1 shows the search queries.

Table 1:

Search queries

| Queries | Restrictions |

|---|---|

|

|

The asterisk (*) after a search term indicates that we searched for variations of the truncated term, enabling us to capture the singular and plural form of a term.

Selection process

To be eligible for inclusion in the review, articles must concern patient portals that give patients access to their personal health records (PHRs), must address a problem encountered in the portal development, and/or must present a solution to a problem. Hence, a broad array of articles was captured, including qualitative and quantitative articles reporting primary research on patient portals; population surveys and simulation studies focused on identifying problems or solutions related to patient portal development; and secondary research such as reviews, commentaries, and conceptual articles. We included both electronic health record (EHR)-tethered portals and “universal PHRs,” so long as the PHRs were clinically integrated, ie, received information that originated in 1 or more EHRs.18 We used the term patient portals to also refer to such PHRs on the grounds that these were accessible through portals.

The included articles were selected through 2 steps. First, each article’s title and abstract were reviewed and articles were excluded that did not meet the just-mentioned eligibility criteria. The primary reviewer (TOT) reviewed all articles, while the second reviewer (AdB) reviewed a random sample of 10%. The agreement rate measured in Cohen’s κ was 0.75 and disagreement was resolved through discussion. In the second step, we used a liberal accelerated approach19 where the first reviewer read the full text and rejected articles that did not comply with the criteria (including 17 articles for which the full text could not be accessed). The second reviewer then received the list of rejected articles for validation. After reading these articles in full, the second reviewer concurred with all but 3 of the decisions, which were discussed until consensus was reached, resulting in 2 articles being added back. We chose the liberal accelerated approach for the second phase because it required fewer resources, while maximizing inclusion, compared with having 2 reviewers read the full text of all papers.20

Data extraction and synthesis

One reviewer extracted information from the articles regarding each of the 5 steps of the problem-solving cycle. The extracted information was sent to the other members of the research team to solicit feedback and comments. The majority of the articles mentioned only 1 problem. However, some articles mentioned multiple problems, in which case we extracted information about each of the addressed problems. Taking an abductive analysis approach that strives to find the most simple and probable explanation of a given observation,21 we then first combined information about problem definitions into “problem categories.” This categorization was based on the problem definitions of the articles. We verified that we had not omitted key categories by comparing our categories with 2 relevant frameworks on patient portal development.13,22 Second, we combined information about factors causing each of the problems in the categories. Third, for each of the problem categories, we ordered information about proposed solutions into themes, each describing a type of solution. Fourth, for the solutions that had been implemented, we gathered information about the solution and the organizational context within which the solution was implemented, specifically the type of health care system setting. According to the problem-solving framework, factors inherent to the organizational context profoundly affect the development process. Thus, we believed it was useful to understand, at a minimum, in which types of systems the solutions were implemented. Fifth, for the implemented solutions that had been evaluated, we took note of evidence from the evaluations.

RESULTS

Study selection

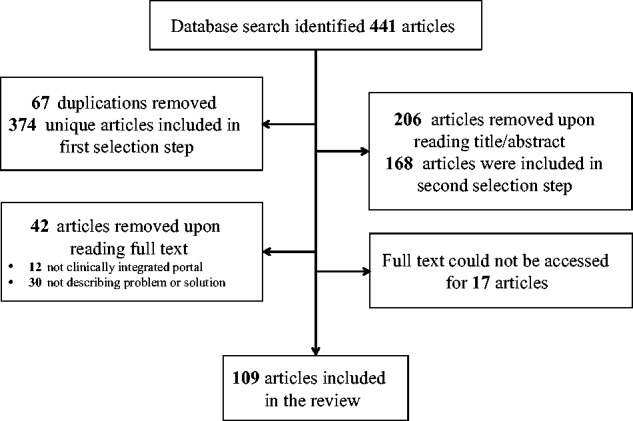

The number of articles retrieved from the initial search was 441. The flow diagram displayed in figure 2 details the selection process that resulted in 109 included articles.

Figure 2:

Flow diagram.

Study characteristics

Sixty-one of the articles presented primary research on actual patient portals, while 27 reported on primary research not specific to a portal, such as population surveys and simulation studies that focused on identifying problems or solutions related to patient portal development. The remaining 21 articles conveyed secondary research such as reviews, commentaries, and conceptual articles. Nonexperimental studies dominated in the pool of selected articles with only 3 quasi-experimental studies and no randomized controlled trials. The vast majority of authors were from North America (85) and Europe (14), with only 10 from Asia, Australia, and South America. Thirty-four of the articles were published between 2005 and 2010, while 75 were from between 2011 and 2015, indicating a considerable increase in research on the topic in most recent years. The online supplementary file displays basic information about the articles. (The numbering assigned to each article in the appendix is used in this text for referencing the articles.)

Synthesis of results

Problem definition

Our categorization of data led to the identification of 5 main problem categories: achieving patient engagement, health service provider engagement, appropriate data governance, security and interoperability, and a sustainable business model. These problems were defined in both primary and secondary research articles.

Problem analysis and diagnosis

For each of the identified problem categories, we provide an account of the factors causing the problems as they have been described in the included literature.

Patient engagement

Seventy-one articles addressed patients’ use of patient portals, several of which remarked that use was generally low (Nos. 9, 15, 22, 37, 40, 45, 46, 49, 50, 58, 74, 96). The articles in this problem category offered 3 explanations for this low use. First, as several articles noted, patient use was limited by patient concerns about confidentiality of their personal health data (Nos. 6, 7, 9, 15, 22, 28, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 48, 50, 56, 72, 84, 98, 99). Second, some patients were unaware that they had access to a portal or did not recognize the usefulness of using one (Nos. 2, 4, 6, 7, 15, 29, 38, 51, 58, 61, 95, 108). Also, some patients had tried using a portal but had negative experiences, perhaps due to a lack of user friendliness (Nos. 2, 22, 33, 84). Third, a major hindrance to engaging patients described in many articles was the lack of digital access (Nos. 2, 3, 7, 29, 36, 38, 41, 45, 51, 55, 58, 99) and/or health literacy (Nos. 2, 3, 7, 23, 28, 41, 45, 47, 49, 50, 51, 55, 56, 58, 70, 79, 85, 90, 91, 109). Patients facing these constraints may not have been able to access a patient portal nor felt empowered to retrieve and apply information. A central topic in the literature was whether some patients, based on demographic and socio-economic characteristics, were less able and prone to use portals than others (Nos. 2, 3, 22, 23, 24, 28, 29, 38, 40, 42, 44, 49, 52, 53, 54, 66, 67, 69, 71, 73, 74, 75, 78, 80, 83, 85, 86, 94, 98, 101, 102, 103, 104, 106, 107), generally associating use with being female, young, white, affluent, and having a chronic disease.

Health service provider engagement

Twenty-two articles described concerns held by providers that hindered them from adopting or using a portal. An often-mentioned aspect was providers’ fears that use of portal features, especially secure email, would increase their workload and disrupt their workflow (Nos. 20, 21, 27, 43, 63, 65, 92, 97, 102) (despite a recent study which found that, on average, secure emailing with patients has not substantially impacted primary care provider workloads23), especially in light of inadequate compensation (Nos. 7, 21). A related concern among providers, as expressed in these and other articles, was that they did not possess the skills and capacities to adjust to technical requirements and new models of patient care induced by electronic means of interacting with patients, which would give patients more control as well as responsibility (Nos. 7, 21, 56, 75, 76). A third aspect revolved around liability in case of breached privacy or harmful patient behavior (Nos. 7, 16, 39, 62, 64, 65, 92, 97, 105); for instance, providers could fail to respond in a timely way to patient inquiries or be required to base clinical decision making on patient-entered data, that may not be accurate nor complete. Further, providers had a concern about their possible liability related to patients who may not be able to interpret clinical content and the resulting anxiety, confusion, and perhaps inappropriate or harmful behavior. Lastly, 2 articles noted that some providers were hesitant to give up autonomy, a consequence of giving patients control over activities traditionally arranged by the providers, such as booking appointments (Nos. #82, 92).

Security and interoperability

Twenty articles touched upon the challenge of establishing secure and stable technical infrastructures on which portals could operate. Two articles made explicit that this problem should be seen in light of nonstandardized technical and semantic language and rules for setting up and managing health information system infrastructures (Nos. 41, 57). To avoid portals becoming “information islands,” it was explicitly recognized in 4 articles that patient portals should be able to receive and transmit data to and from several EHRs (Nos. 23, 32, 41, 92). Thus, an important problem is achieving data exchange, especially in contexts with noninteroperable EHR systems (Nos. 38, 92, 41). The data exchange problem also extends to establishing a bidirectional flow of data between the EHR and the portal as well as between the portal and external web sources (Nos. 5, 32, 92). For systems to exchange data, they must be able to identify and verify the owners of the data and corresponding records, making the establishment of robust authentication mechanisms a focus of several articles (Nos. 37, 48, 57, 75, 81, 89, 92). Another aspect, which was described in 2 articles, is the importance of protecting against security breaches from, for instance, hacking or inappropriate system use (Nos. 18, 38, 68). At the same time, 5 articles noted that ramping up security measures typically lowers the flexibility and friendliness of use (Nos. 7, 17, 37, 75, 92).

Data governance

Appropriate data protecting and handling was the focus of 16 articles. A notion in some of these was that national data regulations (such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in the United States) do not cover patient portal developers and the hosting organization, causing uncertainty about appropriate data governance (Nos. 38, 41, 64, 77). This uncertainty centered on 3 main aspects. The first is data transparency, ie, what data (such as clinical notes, test results, and problems lists) should be included in the PHR, when to make these data available, and in what way to convey them (Nos. 7, 13, 19, 32, 26). This problem is augmented by the fact that data have traditionally been recorded for an expert audience as opposed to lay people (No. 26). A second aspect of uncertainty concerned authorization/privacy control—who should have access to records and who should be able to determine such access rights (Nos. 13, 16, 19, 26, 32, 38, 77). Examples are whether minors should have access to portals and whether patients should be able to assign proxy access to their informal caregivers. Several of the articles point out that, in situations where patients can choose to extend access to other people, some patients may not be able to properly manage the activities of the people to whom they have extended access (Nos. 16, 77). A third aspect is how to guarantee data integrity—that is, the accuracy and completeness of data (Nos. 16, 19, 57, 87). The question often raised was that when data in the record could be altered and complemented, how well such revisions would be visible in the record.

Sustainable business model

Nine articles concerned the problem of developing a sufficiently sound business model for patient portals. Two main topics were discussed under this problem category. First, there are inadequate and often contradictory reimbursement structures for services provided electronically (Nos. 19, 21, 22, 36, 38, 60, 93). Even with the Meaningful Use program, the incentives are often too modest (and the thresholds too high) to create an adequate business case (No. 60). The second issue is the lack of documented cost savings from using patient portals, attainable, for example, through better-managed patients or administrative efficiencies (Nos. 7, 19, 38, 59).

Design of solutions

Forty-five articles reporting on both primary and secondary research proposed solutions to ameliorate these problems.

Patient engagement

Seventeen articles discussed how to better engage patients to use patient portals, the majority of which mentioned using participatory design approaches (Nos. 12, 23, 31, 33, 36, 46, 52, 70, 72, 75, 84, 88, 100, 108). Designing portals to meet needs defined by patients’ characteristics, preferences, and capacities, as opposed to the most easily operationalized features of the technology, is believed to result in portals with high patient-perceived usefulness and usability. One example is the translation of content to minority languages (No. 36). As described in many of these articles, such patient-centered designs are achieved through patient interviews, surveys, and focus groups or through actual usability testing where patients are observed while using the portal. A second way to engage patients, with particular emphasis on those lacking access and skills, is via training these patients in the use of portals (Nos. 2, 26, 33, 47, 55, 67) or providing access through, for example, onsite kiosks (No. 2). Three articles reported on actual training programs offered to patients, especially to vulnerable patients with low Internet skills (Nos. 47, 55, 67). Lastly, a couple of articles mentioned promotion initiatives as helpful for attracting patient attention and increasing awareness. This can be either through encouragement by providers (Nos. 2, 52), through providing written or visual materials (Nos. 33, 46, 61, 102), or follow-up registration reminders (No. 29).

Health service provider engagement

Ten articles suggested ways to enhance provider engagement by improving their attitudes toward patient portals. Four articles suggested providing communication and practical training to providers to equip them to handle technical, interpersonal, and workflow aspects of portal use (Nos. 20, 26, 56, 92). Three out of these 4 articles also suggested introducing information about EHRs and PHRs into the medical and nursing school curricula (Nos. 20, 56, 92). Three articles described how using workflow engineering to mirror current workflow and capitalizing on existing provider roles could inform minimal burden workflow revisions (Nos. 11, 30, 34). As a concrete example, 1 article explained how completed care plans were not transmitted to a relevant provider until 2 weeks prior to the scheduled visit (No. 3). Two of the 10 articles made explicit that involving providers in this process was important in fully understanding their work environment and tasks (Nos. 11, 75). Ways to appease providers’ liability-related concerns were addressed in 2 articles. One suggested notifying providers if patients had not opened an email, while the other proposed designing the system to detect messages that signal medical urgency (Nos. 62, 64).

Security and interoperability

Thirteen articles suggested ways to improve the security for patient portals. Of these, several discussed the feasibility of setting up various types of authentication mechanisms (Nos. 17, 25, 48, 57, 75, 81, 89) such as the so-called Public Key Infrastructures. (Public Key Infrastructures are sets of hardware, software, people, policies, and procedures needed to create, manage, distribute, use, store, and revoke digital certificates.24) Three articles expressed the importance of standardizing interoperability guidelines to allow for data exchange among organizations such as the international Health Level 7 (HL7) standard (Nos. 7, 8, 68). Two articles proposed achieving data exchange by setting up (Regional) Health Information Exchanges that can standardize data and facilitate exchange among different organizations (Nos. 23, 38). One article suggested circumventing the need for interorganizational data exchange by letting patients act as mediators (No. 39). A few articles discussed ways to improve system security through encryption tools, firewalls, and audits of adherence to security protocols (Nos. 17, 75).

Data governance

Nine articles suggested solutions to data governance problems. Of these, the majority addressed policies for data availability and timing (Nos. 10, 13, 26, 30, 32, 64), 4 of which described actual policies defined in organizations that have implemented portals (Nos. 10, 30, 32, 64). In these cases, as much data as possible (except for test results prohibited by state laws such as for cancer and HIV) were made available to patients. In at least 2 of these organizations, the timing of certain test results was tuned to provider workflow to allow for quick provider follow-up. Four articles suggested ways to authorize patients to view data (Nos. 8, 16, 32, 64). In most cases, patients had to show identification in person before gaining access to a portal, while an electronically signed user agreement sufficed in others. One article explicitly mentioned that patients were allowed to delegate access to 1 proxy (No. 64). Lastly, with regards to data integrity, 3 articles commented that systematic use of electronic signatures could be a viable way to clearly determine who had revised the records (Nos. 1, 8, 57).

Sustainable business model

Two articles addressed solutions to ensure a sustainable business model. One article advised organizations to negotiate a trial period before committing to purchasing a portal. This would allow organizations to test usability and be better able to estimate financial and organizational effects of using a portal (No. 59). The other article was committed to developing and testing reimbursement criteria for secure messaging that could be used by payers to determine whether and by how much to reimburse an online encounter (No. 93).

Implementation of solutions

Eighteen of the studies reported some form of implementation of solutions in an actual patient portal, which is the only requirement we imposed for a solution to be classified as “implemented” (Nos. 5, 8, 10, 11, 12, 20, 30, 32, 39, 46, 55, 61, 64, 67, 70, 88, 100, 102). The most commonly implemented solutions were aimed at solving problems in the patient engagement category followed by solutions in provider engagement, data governance, and security and interoperability categories. There were none in the sustainable business case category. Interestingly, in terms of the organizational context, 14 of the solutions were implemented in portals within single organizations or organized care delivery systems, while 4 of the portals were provided in collaboration between individual organizations.

Evaluation of solutions

Of the 18 solutions implemented in the actual portals reported above, 5 (Nos. 20, 46, 55, 61, 67) reported on (perceived) effects of the implementation. All of these were in the patient and provider engagement categories. These 5 evaluations collected data on the implementation of secure messaging curricula in residency training (No. 20), strategies to promote portals to patients (Nos. 46, 61), and patient training and guidance (No. 55, 67), and demonstrated that these solutions can ameliorate problems of achieving patient and health service provider engagement. Only 1 (No. 61) of the studies involved a controlled design, while the remaining 4 were uncontrolled qualitative or quantitative before-and-after studies.

Table 2:

Summary of review findings

| Development Problems | Solutions |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aEffect of solution has been evaluated.

DISCUSSION

The review provides valuable insights into problems, diagnoses, and possible solutions described in an emerging field of research. Held up against the problem-solving cycle, we note that of the 109 articles, 45 reported to have made it past the problem analysis and diagnosis to propose solutions. Of these, 18 reported implementation, of which 5 reported evaluation, thus evidencing to have gone “full circle” at least once. None of these articles described the problem-solving process in enough detail for the reader to understand the iterations and dynamics of the process. This does not necessarily mean that the problem-solving process was not completed. The stages not reported may simply have been disregarded in the publication. Yet, in view of the modest number of evaluated designs and the relatively weak evidence, we refrain from presenting evidence-based suggestions for solving the problems encountered in patient portal development. We also refrain from assessing the quality of the solutions that have been proposed but for which no implementation is reported. That being said, the review does provide a basis for further reflection on the nature of the evidence base and recommendations for how it can best be advanced to inform practice. Moreover, the references and appendix may direct the reader to relevant studies of interest.

Further reflection on the evidence base

There appears to be a great deal of attention on patient engagement in scientific literature. Especially, we note that a large proportion of articles are dedicated to examining socio-economic factors associated with portal use. Fewer, but still a considerable number of articles, address problems and solutions related to securing provider engagement, appropriate data governance, and security and interoperability. In comparison, few articles deal with the financial sustainability of patient portals. Furthermore, aside from patient engagement and provider engagement, we have noted no evaluated solutions in the other categories. The uneven nature of the evidence base hinders portal developers from comprehending and solving all problems that affect patient portal development, problems that may be interrelated; for example, lack of financial sustainability will likely hinder provider engagement, even if providers think positively about using a portal. As such, it appears that the current evidence base informs only part of an effective development process.

Further, according to the problem-solving framework, the development process is affected by the organizational context. For instance, it is likely that implementing solutions in portal developments within fragmented care delivery contexts is most difficult, since several organizations typically must join forces to develop a comprehensive portal. Although achieving patient engagement, health service provider engagement, security and interoperability, appropriate data governance, and a sustainable business model is challenging within 1 organization, this challenge is likely exacerbated by the necessity to solve problems across organizations with varying patient populations, provider attitudes and incentives, existing technical infrastructures, internal regulatory policies or beliefs, and short- and long-term objectives and profit motives. However, we found that the vast majority of the implemented solutions was from within single organizations or organized care delivery systems. Thus, these types of organizational contexts appear to provide the test bed for most patient portal developments, which may limit the relevance of current research to other organizational contexts.

Recommendations for future research

Future research should seek to systematically improve our comprehension of what patient portal solutions actually work, for whom, and in what contexts. We offer 3 main recommendations for such research efforts.

Where available, we encourage researchers to base their designs on existing evidence and report implementation and evaluation so as to validate, advance, and generalize existing evidence. Where there is no evidence, such as on how to secure financial sustainably, we encourage research that identifies and analyzes problems in addition to designing, implementing, and evaluating solutions so as to create a more well-rounded evidence base.

Patient portal development occurs through multiple iterations of the problem-solving cycle. Hence, we call for studies with an extended “unit of analysis” in terms of a longer time horizon and several iterations of the process.

To be able to inform portal development across contexts, the evidence base could benefit from research that accumulates knowledge from different types of patient portals, patient populations, and across organizational contexts (and especially within fragmented care delivery contexts where portal development problems may be most severe).

Study limitations

By only including articles written in English, we have excluded many articles published in other languages. Further, we restricted our review to peer-reviewed studies, foregoing sources such as websites of specific patient portals, high-level policy and strategy documents issued by governments, or large knowledge institutes. To advance the depth of understanding about development problems and solutions in various contexts, our review could have benefited from inclusion of such gray literature from several countries.

The dominance of articles addressing user engagement may be explained by the fact that we excluded articles that focused on EHRs and Health Information Exchanges more broadly; since patient portals typically tie into existing health information technology infrastructures, insight into earlier design and development stages of these infrastructures are important to fully comprehend portals (for example, see reference Nos. 25–32). Hence, while it was outside of the scope of this review, we might have obtained a more even distribution of insights across problem categories if we had opened up the review to also include EHRs and Health Information Exchanges.

Finally, by focusing on development problems, we may have excluded some articles that solely reported on successes; however, these could also provide important guidance to patient portal implementers. In addition, there is the probability of publication bias towards studies of implemented solutions with clear results. Consequently, the evidence base included in this study may underreport on development successes as well as nonimplemented or poorly implemented solutions.

CONCLUSION

With this review, we conclude that few studies systematically report on the patient portal development processes. As a result, the review does not provide an evidence base for portal development. Yet, our findings support a set of recommendations for advancement of the evidence base: we posit that future research should build on existing evidence, draw on principles from design sciences conveyed in the problem-solving cycle, and seek to produce evidence within various different organizational contexts.

CONTRIBUTORS

TOT conceived of the study, conducted the search, selected the included articles, contributed significantly to the analysis of data, and drafted the manuscript. AdB contributed significantly to the selection of articles, data analysis, and made substantial contributions to the manuscript by revising it critically for important intellectual content. TR contributed significantly to the data analysis and made substantial contributions to the manuscript by revising it critically for important intellectual content. JvdK contributed significantly to the data analysis and made substantial contributions to the manuscript by revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Innovation Fund of the Institute of Health Policy & Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam. No grant number is available.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Aligning Forces for Quality. Lessons Learned. The Value of Personal Health Records and Web Portals to Engage Consumers and Improve Quality 2012. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2012/rwjf400251. Published July 2012 (accessed 5 Sept 2013).

- 2.Detmer D, Bloomrosen M, Raymond B, et al. Integrated personal health records: transformative tools for consumer-centric care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008;8:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otte-Trojel T, de Bont A, Rundall T, et al. How outcomes are achieved through patient portals: a realist review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21(4):751–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldzweig CL, Towfigh AA, Paige NM, et al. Systematic review: secure messaging between providers and patients, and patients’ access to their own medical record. Evidence on Health Outcomes, Satisfaction, Efficiency and Attitudes. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK100359/pdf/TOC.pdf. VA-ESP Project #05-226, 2012. Published July 2012 (accessed 22 Feb 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Hoerbst A. The impact of electronic patient portals on patient care: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Med Internet Res 2012;14(6):e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tenforde M, Jain A, Hickner J. The value of personal health records for chronic disease management: what do we know? Fam Med 2011;43(5):351–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osborn CY, Mayberry LS, Mulvaney SA, et al. Patient web portals to improve diabetes outcomes: a systematic review. Curr Diab Re. 2010;10(6):422–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bates DW, Wells S. Personal health records and health care utilization. JAMA 2012;308(19):2034–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins SA, Vawdrey DK, Kukafka R, et al. Policies for patient access to clinical data via PHRs: current state and recommendations. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:i2–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruse CS, Bolton K, Freriks G. The effect of patient portals on quality outcomes and its implications to meaningful use: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2015;17(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wynia MK, Williams Torres G, Lemieux J. Many physicians are willing to use patients’ electronic personal health records, but doctors differ by location, gender, and practice. Health Aff 2011;30(2):266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, et al. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13(2):121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakefield DS, Mehr D, Keplinger L, et al. Issues and questions to consider in implementing secure electronic patient–provider web portal communications systems. Int J Med Inform 2010;79(7):469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Aken JE. Management research based on the paradigm of the design sciences: the quest for field-tested and grounded technological rules. J Manag Studies 2004;41(2):219–46. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beuscart-Zéphir MC, Pelayo S, Bernonville S. Example of a Human Factors Engineering approach to a medication administration work system: potential impact on patient safety. Int J Med Inform 2010;79(4):e43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Aken JE, Berends H, van der Bij Problem Solving in Organizations. 2nd ed New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.PRISMA checklist. PRISMA Statement Website. http://www.prisma-statement.org/2.1.2%20-%20PRISMA%202009%20Checklist.pdf (accessed 22 Feb 2015).

- 18.Caligtan CA, Dykes PC. Electronic health records and personal health records. Semin Oncol Nurs 2011;27(3):218–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, et al. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 2012;1:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci 2010;5(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavory I, Timmermans S. Abductive Analysis: Theorizing Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otte-Trojel T, de Bont A, Aspria M, et al. Developing patient portals in a fragmented healthcare system. Int J Med Inform 2015, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrido T, Meng D, Wang JJ, et al. Secure e-mailing between physicians and patients: transformational change in ambulatory care. J Amb Care Manag 2014;37(3):211–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.RSA Data Security. Understanding Public Key Infrastructures (PKI). http://storage.jak-stik.ac.id/rsasecurity/understanding_pki.pdf. Published 1999 (accessed 30 Mar 2015).

- 25.Dogac A, Yuksel M, Avcı A, et al. Electronic health record interoperability as realized in Turkey’s National Health Information System. Methods Inform Med 2011;50(2):140–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge Y, Ahn DK, Unde B, et al. Patient-controlled sharing of medical imaging data across unaffiliated healthcare organizations. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20(1):157–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halford S, Obstfelder A, Lotheringon A. Changing the record: the inter-professional, subjective and embodied effects of electronic patient records. New Tech Work Employ 2010;25(3):210–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin D, Mariani J, Rouncefield M. Managing integration work in an NHS electronic patient record (EPR) project. Health Inform J 2007;13(1):47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinze O, Birkle M, Köster L, et al. Architecture of a consent management suite and integration into IHE-based regional health information networks. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2011;11(58), http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/11/58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lapsia V, Lamb K, Yasnoff WA. Where should electronic records for patients be stored? Int J Med Inform 2012;81(12):821–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen E, Mydske PK. Developing electronic cooperation tools: a case from Norwegian Health Care. Eysenbach G, ed. Interactive J Med Res 2013;2(1):e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudin RS, Simon SR, Volk LA, et al. Understanding the decisions and values of stakeholders in health information exchanges: experiences from Massachusetts. Am J Pub Health 2009;99(5):950–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]