Abstract

Each Drosophila muscle is seeded by one Founder Cell issued from terminal division of a Progenitor Cell (PC). Muscle identity reflects the expression by each PC of a specific combination of identity Transcription Factors (iTFs). Sequential emergence of several PCs at the same position raised the question of how developmental time controlled muscle identity. Here, we identified roles of Anterior Open and ETS domain lacking in controlling PC birth time and Eyes absent, No Ocelli, and Sine oculis in specifying PC identity. The windows of transcription of these and other TFs in wild type and mutant embryos, revealed a cascade of regulation integrating time and space, feed-forward loops and use of alternative transcription start sites. These data provide a dynamic view of the transcriptional control of muscle identity in Drosophila and an extended framework for studying interactions between general myogenic factors and iTFs in evolutionary diversification of muscle shapes.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.14979.001

Research Organism: D. melanogaster

eLife digest

Animals have many different muscles of various shapes and sizes that are suited to specific tasks and behaviors. The fruit fly known as Drosophila has a fairly simple musculature, which makes it an ideal model animal to investigate how different muscles form.

In fruit fly embryos, cells called progenitor cells divide to produce the cells that will go on to form the different muscles. Proteins called identity Transcription Factors are present in progenitor cells. Different combinations of identity Transcription Factors can switch certain genes on or off to control the muscle shapes in specific areas of an embryo. However, progenitor cells born in the same area but at different times display different patterns of identity Transcription Factors; this suggests that timing also influences the orientation, shape and size of a developing muscle, also known as muscle identity.

Dubois et al. used a genetic screen to look for identity Transcription Factors and the roles these proteins play in muscle formation in fruit flies. Tracking the activity of these proteins revealed a precise timeline for specifying muscle identity. This timeline involves cascades of different identity Transcription Factors accumulating in the cells, which act to make sure that distinct muscle shapes are made. In flies with specific mutations, the timing of these events is disrupted, which results in muscles forming with different shapes to those seen in normal flies. The findings of Dubois et al. suggest that the timing of when particular progenitor cells form, as well as their location in the embryo, contribute to determine the shapes of muscles.

The next step following on from this work is to use video-microscopy to track identity Transcription Factors when the final muscle shapes emerge. Further experiments will investigate how identity Transcription Factors work together with proteins that are directly involved in muscle development.

Introduction

The morphological diversity of body wall muscles is necessary for precision, strength and coordination of body movements specific to each animal species. The development of the complex architecture of the body wall musculature of the Drosophila larva – 30 different muscles in each hemi-segment (Bate, 1993) – is a classical model to decrypt transcription regulatory networks controlling muscle morphological diversity. Each muscle is a single multinucleated fiber built by fusion of a Founder Cell (FC) with fusion competent myoblasts (FCMs). Muscle identity - orientation, shape, size, attachment sites - reflects the expression by each FC of a specific combination of identity Transcription Factors (iTFs). Establishment of the FC iTF code starts with activation of specific muscle iTFs, in response to positional information from the ectoderm which defines equivalence groups of myoblasts within each segment, called promuscular clusters (PMCs) (Carmena et al., 1995; Baylies et al., 1998). The second step is the selection of progenitor cells (PCs) from each PMC, via interplay between Ras signaling and Notch (N)/Delta-mediated lateral inhibition, the unselected myoblasts becoming FCMs (Carmena et al., 2002). The third step is the asymmetric division of each PC into two FCs or, in some cases, one FC and one adult muscle precursor cell (AMP) or pericardial cell. Asymmetric division leads to maintaining expression of some iTFs in one FC and their repression by N signaling in the sibling cell, thereby contributing to muscle lineage diversity (Ruiz-Gomez et al., 1997; Carmena et al., 1998). This henceforth classical, three-step model of muscle identity specification relies heavily on positional information conferring each muscle its identity (Tixier et al., 2010). Interestingly, pioneering studies showed that specification of two nearby Even-skipped (Eve) expressing PCs was sequential (Buff et al., 1998; Halfon et al., 2000), but the link between PC birth time and muscle identity remained to be explored.

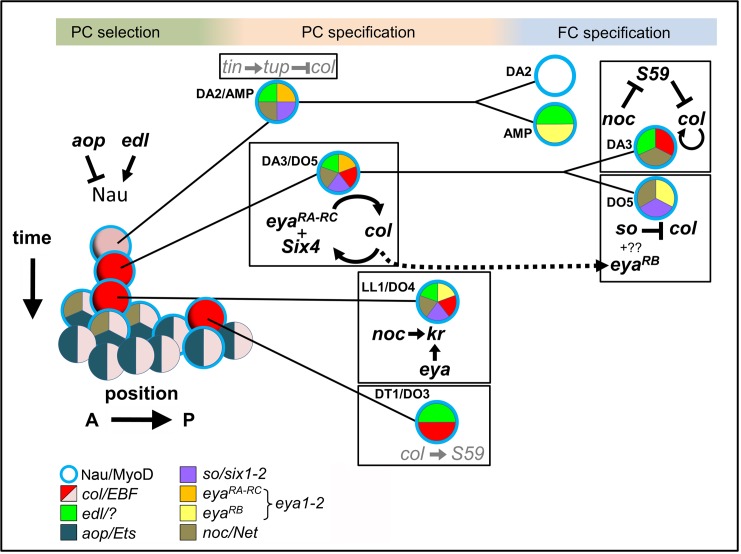

We have previously shown that four PCs, at the origin of one dorsal muscle (DA2) and one AMP, and the 6 dorso-lateral (DL) muscles, DA3, DO3, DO4, DO5, DT1, and LL1, are serially selected from a PMC expressing Collier (Col/Kn, Early B-Cell Factor (EBF) in vertebrates (Daburon et al., 2008). More precisely, the DA2/AMP, DA3/DO5 and LL1/DO4 PCs are sequentially selected at roughly identical positions in thoracic and abdominal segments, while the DO3/DT1 PC is selected at a slightly posterior position and only in abdominal segments (Boukhatmi et al., 2012; Enriquez et al., 2012; Figure 1A). Beyond the PC step, col transcription is only maintained in the DA3 muscle (Crozatier and Vincent, 1999), while other iTFs, the C2H2 zinc finger protein Krüppel (Kr), the homeodomain protein S59 (vertebrate NKx1.1) and the Lim-homeodomain protein Tailup (Tup/Islet1) are expressed in the LL1, DT1 and DA2 lineages, respectively (Dohrmann et al., 1990; Ruiz Gomez and Bate, 1997; Boukhatmi et al., 2012). Serial emergence of DL PCs, followed by lineage-specific expression of different iTFs, raised the question of how PC selection timing and muscle identity were linked. The discovery that Tup expression led to col repression in the DA2/AMP PC, thereby distinguishing between DA2 and DA3 identities, provided a first insight into this question. We indeed found that the time lag between DA2/AMP and DA3/DO5 PC selection coincides with the period of dorsal regression of Tinman (Tin; vertebrate Nkx2.5) expression (Johnson et al., 2011), such that only the first-born DA2 PC inherits Tin levels above the threshold required for activation of tup and imposing a DA2 fate. Yet, our understanding of how conjunction of developmental time and position translates into muscle-specific iTF codes, remained fragmentary.

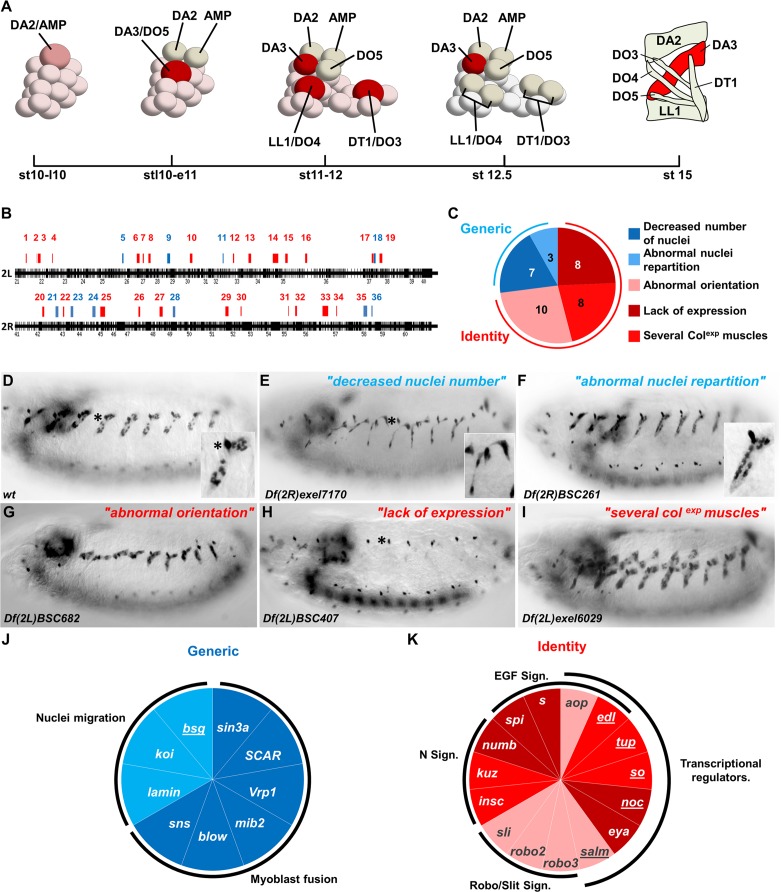

Figure 1. Genetic identification of muscle identity genes.

(A) Diagrammatic representation of the sequential emergence of four PCs (large cells) from the Col expressing PMC, followed by PC into FC divisions (embryonic stages (st) 10–12.5) and the corresponding muscle pattern at stage 15. The name of each PC, FC and muscle is indicated. Col expression is in red, color intensity indicating expression level. (B) Gene density along chromosome 2L and 2R, schematized by black bars. Position and size of each of 36 regions identified in our screen are indicated by red or blue bars. (C) Pie chart showing repartition of the DA3 phenotypes into two classes of generic (blue), and identity (red) defects. (D–I) Col immunostaining of late stage 15 embryos; (D) wt and (E–I), representative examples (deficiency name indicated) of each phenotypic class. The asterisk in (D,E,H) labels a dorsal class IV md neuron expressing Col. In this, and following figures, lateral views of embryos are shown, anterior to the left. (J,K) Pie charts associating individual genes with generic myogenic (K) or identity (L) mutant phenotypes. See also Figure 1—source data 1 for phenotypes.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.14979.003

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. EGF-R signaling is required for a normal pattern of DL muscles.

Here, we identified several new muscle TFs, starting from a systematic deficiency screen of the second chromosome, i.e., roughly 40% of the Drosophila genome. We describe the roles of No Ocelli (Noc), a NET family zinc finger protein (Cheah et al., 1994), Sine oculis (So), a member of the Six family of homeodomain proteins (Cheyette et al., 1994; Serikaku and O'Tousa, 1994; Kenyon et al., 2005), and the co-factor ETS domain lacking Edl (Baker et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2003; Qiao et al., 2006) in DL muscle development, and in more detail, roles of Eyes-absent (Eya), a partner of Six proteins (Pignoni et al., 1997), and Anterior open (Aop), an Ets-domain transcription repressor (Rebay and Rubin, 1995; Xu et al., 2000). Analysis of the aop, edl, eya, noc and so muscle mutant phenotypes and time windows of transcription, combined with col transcription in the different mutant contexts, revealed a cascade of regulations including coherent and incoherent feed-forward loops, which link PC selection time to muscle identity. aop and edl control the temporal sequence of DL PC selections, eya is required in PCs for maintaining iTF transcription, while so and one eya-specific isoform are deployed at the FC step. Finally, noc regulates expression of other iTFs, at the PC or FC step, depending upon the muscle lineage. Integration of these new data with pre-existing knowledge provides a comprehensive, dynamic view of the transcriptional control of muscle identity in Drosophila, and an extended framework for studies of interactions between general myogenic factors such as Nautilus (Nau)/MyoD and Eya, and iTFs in the diversification of muscle lineages during animal evolution.

Results

A genetic screen for muscle defects

In order to identify new muscle identity genes, we screened a collection of 389 overlapping deficiencies, each deleting between 10 and 15 genes, and together covering about 80% of the Drosophila second chromosome (Chanut-Delalande et al., 2014). Homozygous deficiency embryos were first examined for DA3 Col expression at the end of the fusion phase, embryonic stage 15. Nuclear Col localization allowed appraisal both of DA3 formation and shape, the number and spatial distribution of DA3 nuclei, and the presence of ectopic Col-expressing muscles. General embryonic defects could be identified by the loss, or gross disturbance of Col expression elsewhere, in the central and peripheral nervous systems, and/or lymph gland (Dubois and Vincent, 2001), and the corresponding chromosomal deficiencies were not considered here. 36 were retained (Figure 1B and Figure 1—source data 1). The observed DA3 phenotypes were divided into two broad classes (Figure 1C): Class 1: Decreased number or abnormal repartition of nuclei (Figure 1E–F compare to Figure 1D); Class 2: Abnormal DA3 orientation and/or either loss of Col expression or ectopic Col expression in additional muscles (Figure 1G–I compare to Figure 1D). Three deletions showing both DA3 abnormal orientation and low nuclei number were considered as class 2 (regions 3, 4 and 30, Figure 1—source data 1). Class 1 phenotypes have previously been observed in myoblast fusion or nuclei migration mutants which affect roughly equally all muscles (Folker et al., 2014; Rushton et al., 1995) and were considered here as 'generic myogenesis' defects (Figure 1C and Figure 1—source data 1). Class 2 phenotypes were reminiscent of either iTF or Notch (N) mutants (Ruiz-Gomez et al., 1997; Crozatier and Vincent, 1999; Tixier et al., 2010) and considered as 'muscle identity' defects (Figure 1C and Figure 1—source data 1).

To identify the gene(s) whose loss caused a DA3 phenotype in mapped deletions, we tested the most promising candidates for which loss of function mutants were available. Genes for which mutants over the deficiency reproduced the deficiency phenotype were selected for further analysis. From a total of 36 different chromosomal regions, we identified 9 genes out of 10 regions linked to generic defects and 15 genes in 14 regions linked to identity defects (Figure 1J,K and Figure 1—source data 1). The relevant gene(s) in 12 other regions remain to be identified. Seven of the nine genes in the generic class encode cytoskeletal or membrane-associated proteins with an already well-known role in either myoblast fusion or nuclei repartition in muscle syncitia, validating our screen (Figure 1J; Kim et al., 2015). The eigth gene is sin3A, a chromatin binding protein present in transcription repressor complexes, also required for a normal pattern of myoblast fusions (Dobi et al., 2014). The 9th gene is basigin (bsg), a predicted igG family plasma membrane protein, interacting with integrin (Curtin et al., 2005), whose role in muscle development has not been assessed.

Among the 15 genes associated with identity phenotypes (Figure 1K), six encoded components of either the N or Robo/Slit signaling pathways, two pathways previously implicated at different steps of DA3 muscle formation (Crozatier and Vincent, 1999; Ordan et al., 2015) and were therefore not further studied. Four other encoded components of the EGF-R signaling pathway: spitz (spi), Star (S), aop (also called yan; Flybase FBgn 000097), and edl (also called mae; Flybase FBgn0023214), while a deficiency (Df(2R)BSC259) removing both mesodermal FGFs, Thisbe and Pyramus, (Stathopoulos et al., 2004) did not show a DA3 phenotype. A complete lack of DA3, DO5, DO4 and LL1 muscles in mutants for either spi (spiIIA), the EGF-R signal, or Star (SIIN), a chaperone protein required for Spi processing (Heberlein and Rubin, 1991), confirmed the central role of Epidermal Growth Factor-Receptor (EGF-R) signaling in specification of these DL muscles (Figure 1—figure supplement 1).

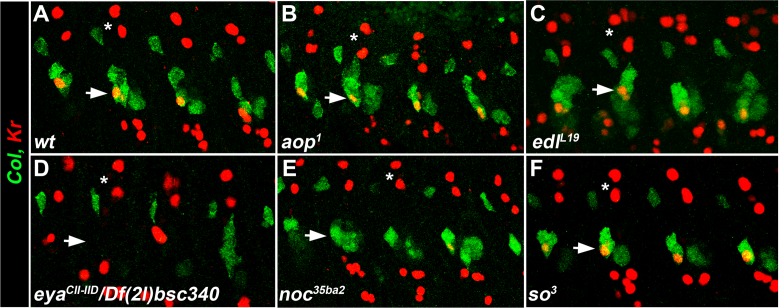

New transcriptional regulators involved in muscle identity

Seven identity genes encoded transcriptional regulators, and potentially, new muscle iTFs: aop, edl, eya, noc, so, spalt major (salm) and tup (Figures 1K and 2A–F). Previous studies showed that the Ets-domain transcription activator Pointed (Pnt), and transcription repressor Aop/Yan (Xu et al., 2000; Rebay and Rubin, 1995), promoted and inhibited the formation of Eve-expressing dorsal PCs, respectively, downstream of EGF-R signaling (Halfon et al., 2000; Carmena et al., 2002). The mesodermal function of edl remained, however, unknown. Comparing the aop and edl phenotypes thus provided an opportunity to further characterize outputs of EGF-R signaling in muscle identity specification. Whereas we previously reported tup function in dorsal muscle identity, neither function of noc, salm nor so in muscle development was previously characterized. Drosophila Six4 and So are orthologous to Six proteins which interact with Eya in mouse myogenic progenitors (Heanue et al., 1999; Relaix et al., 2013). eya was proposed to interact with Six4 in Drosophila somatic muscle development, both genes showing similar expression patterns (Clark et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2009). Our identification of so mutants in our screen and the difference between the eya and so phenotypes (Figure 1—source data 1) called for a detailed comparison of eya and so expression and function in muscle PCs.

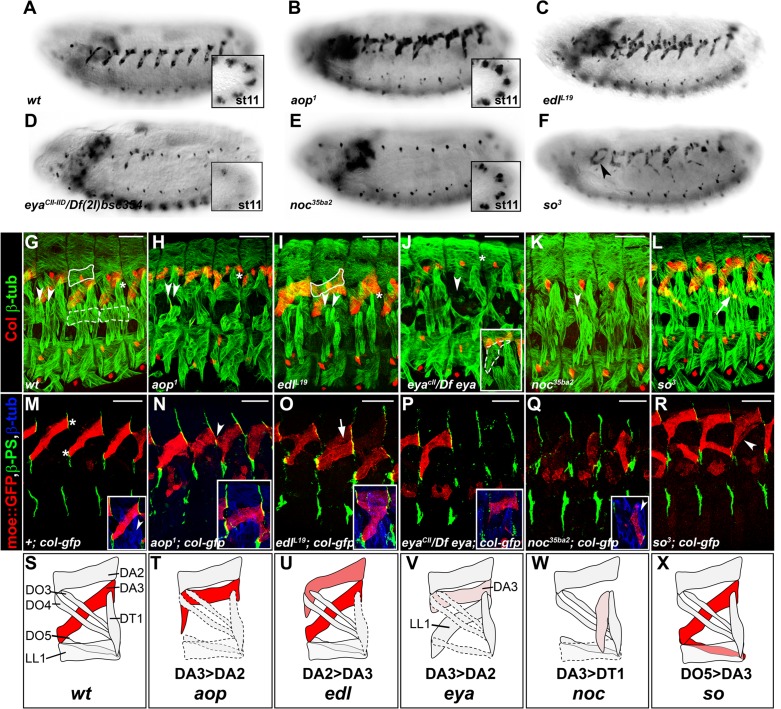

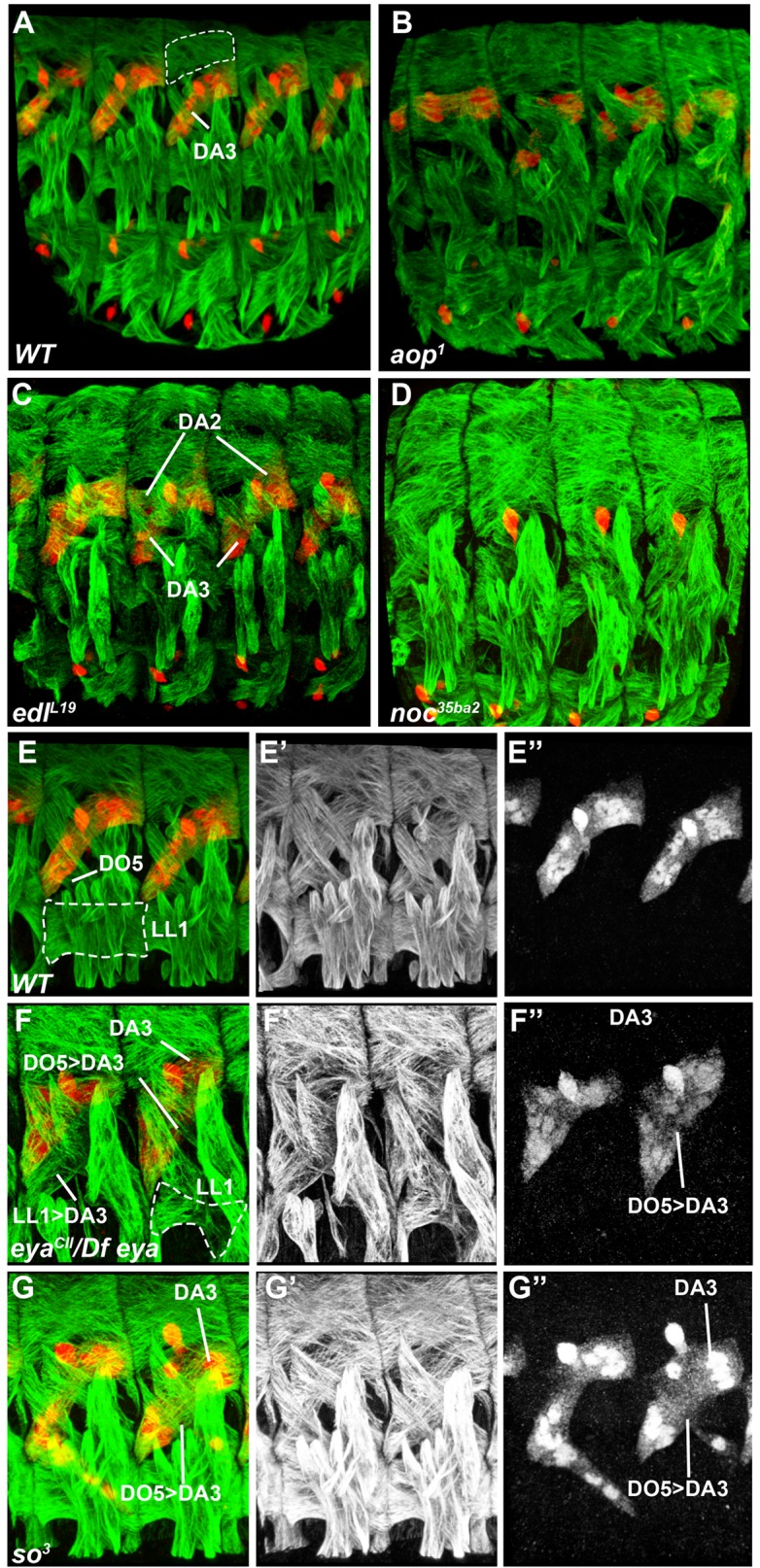

Figure 2. Specific muscle patterning defects in aop, edl, eya, noc and so mutant embryos.

(A–F) Late stage 15 embryos stained for Col, to visualize the DA3 muscle. (A) wt, (B–F) embryos homozygous mutant for aop, edl, eya, noc and so null alleles with their names indicated. Inserts in (A,B,D,E) show Col expression in PCs, stage 11. (G–L) stage 16 embryos stained for Col (red) and β3-tubulin (green) to visualize all body wall muscles; arrowheads point to LT1 and LT2, asterisks indicate DT1; DA2 is surrounded by a line in G,I, and LL1 by a dotted line in G. (G) wt embryo. (H) aop1 (I) edll19; Col is expressed in DA2 and DA3. (J) eyaCII/Df(2L)BSC354; DA3 Col expression is lost; inset, LL1>DA3 transformation. (K) noc35ba2: Col expression is lost. (L) so3; Col expression in DO5 (arrow). (M–R) Stage 16 embryos stained for β3-tubulin (blue), βPS integrin (green), to visualize tendon cell-muscle connections and moeGFP (red) expressed under control of a DA3-specific col CRM (colLCRM), abbreviated col-gfp. Only βPS integrin and moeGFP are shown, except insets. (M) wt; DA3 ventral and dorsal attachment along the anterior and posterior segmental borders, respectively, are indicated by asterisks; inset, DT1 (arrowhead). (N) aop; DA3 with both DA3 and DA2-like (arrowhead) anterior attachments; DA3>DA2 transformation, inset. (O) edl: moeGFP expression in DA2 and DA3 (arrow and inset). The arrow indicates partial DA2>DA3 transformation; inset, bifid anterior DA3 attachment. (P) eya: moeGFP is lost in most segments or indicates partial or complete (inset) DA3>DA2 transformation. (Q) noc: DA3>DT1 transformation, resulting in DT1 (arrowhead in inset) duplication. (R) so: moeGFP expression in DO5; DO5>DA3 transformation (arrowhead) in some segments. (S–X) Schematic diagram of the most frequent DA2 and DL muscle phenotypes in aop, edl, eya, noc and so mutants; Col expression is in red; see Figure 2—source data 1 for statistics. Bars: 30 μm

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.14979.006

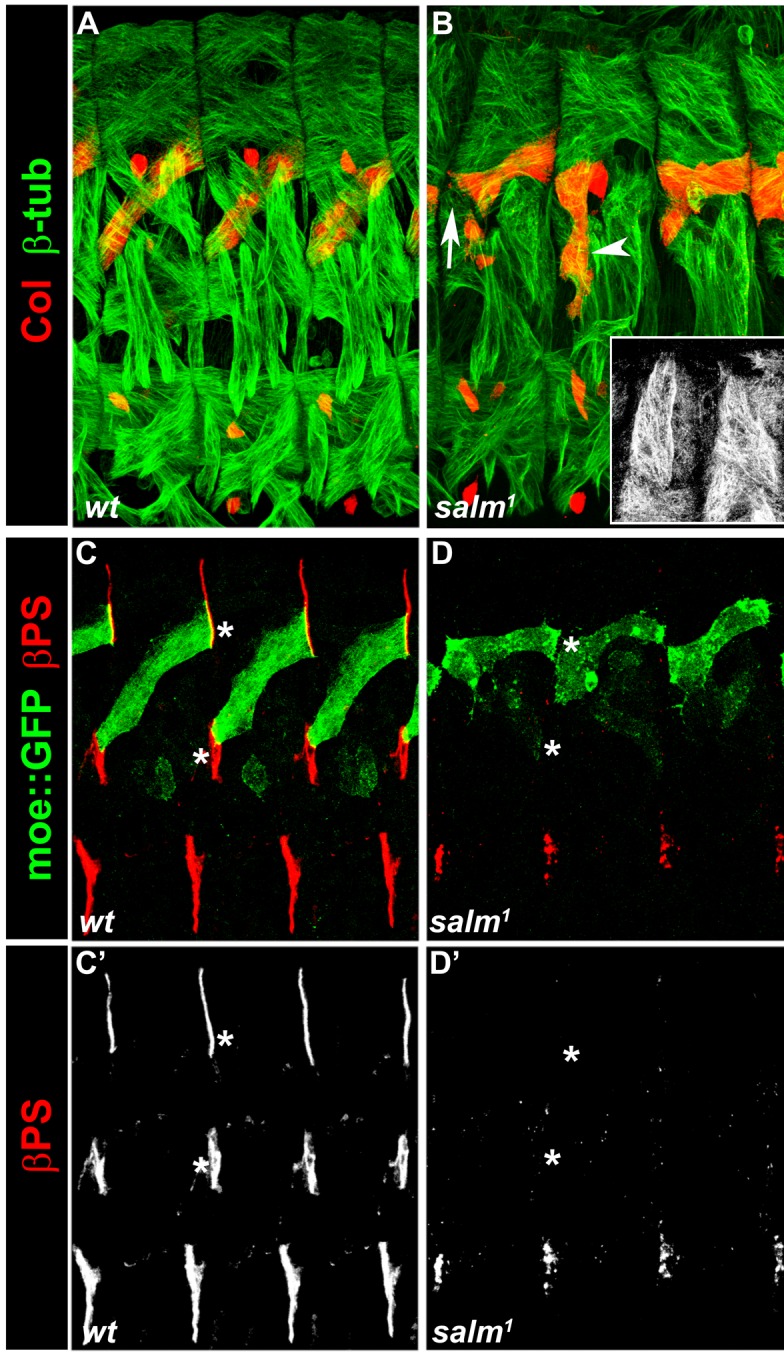

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. salm1 is required for proper skeletal attachment and morphology of the DA3 muscle.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Snapshots for Videos 1–6.

aop, edl, eya, noc and so muscle phenotypes

To better assess the muscle phenotypes associated with each mutant, we examined the pattern of DL muscles in late stage 15 embryos immunostained for β3Tubulin, using Col staining to visualize DA3 (Figure 2G–L, Video 1). In addition, we introduced the DA3-specific colLCRM-moeGFP reporter gene (Enriquez et al., 2012), to precisely visualize the DA3 contours in these mutant backgrounds. Stability of the MoeGFP fusion protein also allowed following 'DA3' muscles in noc and eya mutants which lack Col expression (Figure 2M–R). In order to verify that muscle phenotypes were not associated with defective tendon cell differentiation, we stained mutant embryos for βPS integrin which accumulates at muscle-tendon junctions (Leptin et al., 1989). Based on this analysis, we eliminated salm (salm1) mutants which exhibited a phenotype reminiscent of defective tendon cells (Schnorrer and Dickson, 2004; Staudt et al., 2005; Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Unlike salm, no βPS integrin accumulation defects were detected in null mutants for aop (aop1), edl (edlL19), noc (noc35ba2), eya (eyaCII-IID), and so (so3) mutants (Figure 2M–R), confirming muscle identity defects.

Video 1. 3-D view of the muscle pattern in stage 16 wt embryos, Figure 2G.

In aop mutants, the DA3 muscle(s) was misshapen in 2/3 of segments (n = 123), with cases of DA3 to DA2 transformation (DA3>DA2; Figure 2B, Figure 2— figure supplement 2, Video 2 and Figure 2—source data 1). The DT1 and LL1 muscles were also malformed in 40% segments (in 48/123 and 47/123 segments, respectively) and lateral and ventral muscles were severely disorganized. The DA2 muscle was unaffected (Figure 2H—and Figure 2—source data 1). colLCRM-moeGFP expression confirmed an abnormal shape of the DA3 muscle suggestive of partial DA3>DA2 transformation (Figure 2N,T). In edl mutants, a second Col-expressing muscle was observed in some segments, sometimes associated with morphological change suggestive of DA2>DA3 transformation (Figure 2C,I, Figure 2— figure supplement 2, Video 3 and Figure 2—source data 1). The DT1 muscle was either absent or too de-structured to be assigned specific identities (in 61/124 segments; Figure 2I). colLCRM-moeGFP expression confirmed a DA2>DA3 transformation in 47% of segments (Figure 2O), but also revealed a number of reciprocal at least partial DA3>DA2 transformations (16/124 segments) (Figure 2O inset—and Figure 2—source data 1). In eya mutants, DA3 Col expression was lost, a loss already observed at the PC stage (Figure 2D,J). Consistent with loss of Col expression early during muscle specification, the DL muscle pattern was severely disorganized in most of segments. The LL1 was absent or oriented like DA3 (in 129/140 segments; Figure 2J, Figure 2— figure supplement 2, Video 4 and Figure 2—source data 1) a phenotype already observed in col mutant embryos (Enriquez et al., 2012). The LT muscles were also often missing and some ventral muscles were absent or malformed, as previously reported (Figure 2J; Figure 2—source data 1) (Liu et al., 2009). Conversely, dorsal muscles and DT1 appeared normal (Figure 2J). colLCRM-moeGFP expression revealed a, sometimes complete or partial, DA3>DA2 transformation (Figure 2P,V). noc mutant embryos also lacked DA3 Col expression at stage 15 (Figure 2E,K and Figure 2, Figure 2— figure supplement 2, Video 5 and Figure 2—source data 1). Contrary to eya mutants, however, Col expression was detected at the PC stage (insets in Figure 2E), indicating a role of noc in maintenance of Col expression in the DA3 lineage. colLCRM-moeGFP expression further revealed that the DA3 could orient like a DT1 in most segments, indicating a DA3>DT1 identity shift resulting in DT1 duplication (Figure 2Q and and Figure 2—source data 1). LT muscles were also affected (Figure 2K). In so mutants, Col ectopic expression was specifically observed in DO5 (Figure 2F,L, Figure 2—figure supplement 2, Video 6, and Figure 2—source data 1). colLCRM-moeGFP expression both confirmed col ectopic expression in the DO5 muscle and its DA3-like orientation in a fraction of segments (Figure 2R, arrowhead, indicating a partial DO5>DA3 identity shift in 79/116 segments (Figure 2F,L and Figure 2—source data 1).

Video 2. 3-D view of the muscle pattern in stage 16 aop1 embryos, Figure 2H.

Video 3. 3-D view of the muscle pattern in stage 16 edlL19 embryos, Figure 2I.

Video 4. 3-D view of the muscle pattern in stage 16 eyaCII/Df(2L)BSC354embryos, Figure 2J.

Video 5. 3-D view of the muscle pattern in stage 16 noc35ba2embryos, Figure 2K.

Video 6. 3-D view of the muscle pattern in stage 16 so3embryos, Figure 2L.

In summary, we found that aop, edl, eya, noc, and so mutants display distinctive patterns of DL muscle defects and DA3 transformations, associated with modifications of Col expression (schematized in Figure 2S–X), indicating that each gene acts in different subsets of DL muscles, and/or at different steps of muscle identity specification.

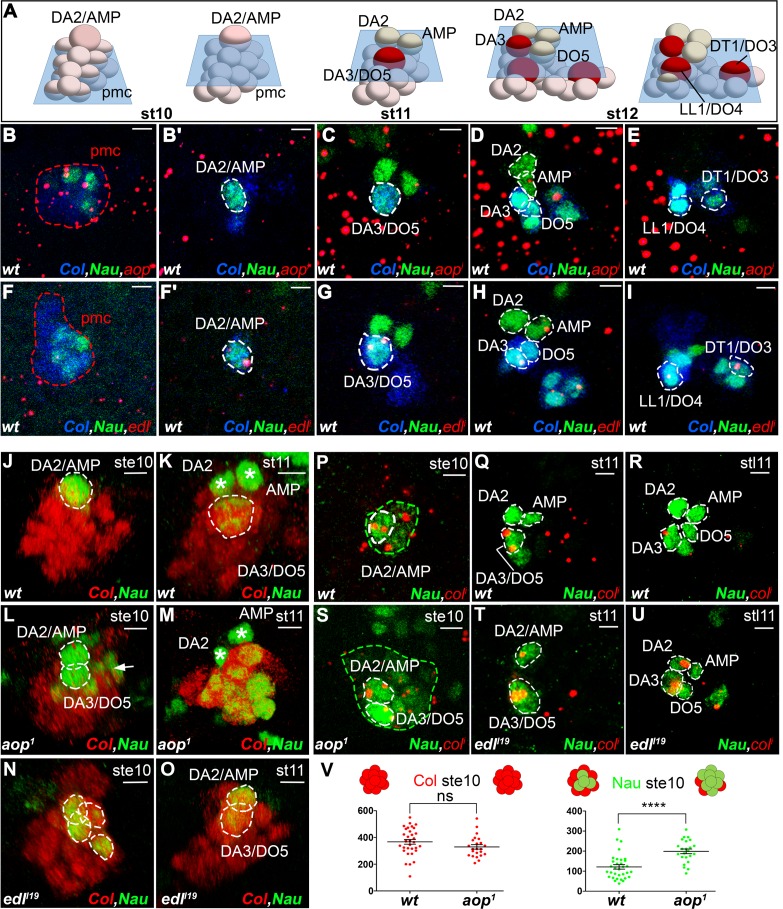

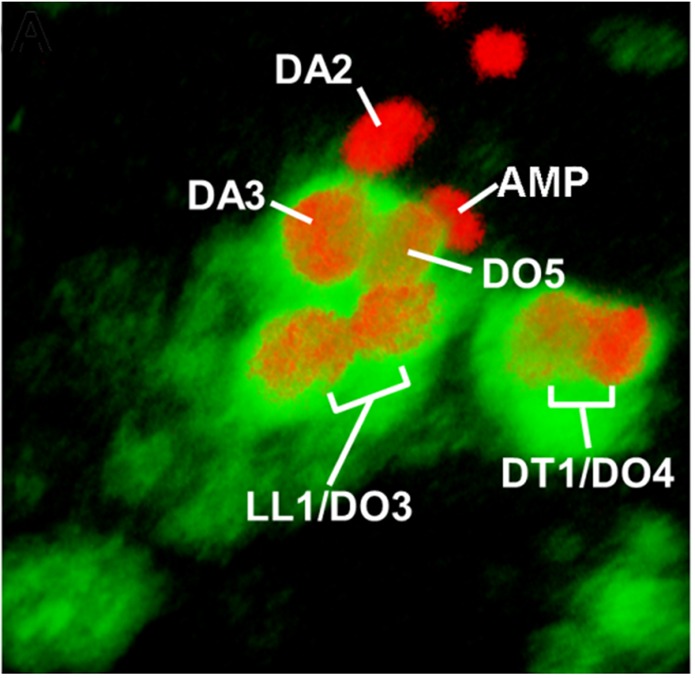

Nau/MyoD is transiently expressed in PMC cells subject to high EGF-R signaling

Understanding the specific muscle transformations observed in aop, edl, eya, noc, and so mutants required determining their expression patterns at the PMC, PC and FC stages. In order to access dynamic aspects of this expression, we used FISH with intronic probes which detect nascent transcripts and allow precisely determining temporal windows of transcription. To follow PC delamination events, we used Nau, the Drosophila ortholog of vertebrate myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), a marker of PCs and FCs (Michelson et al., 1990; Nose et al., 1998). High-resolution 3-D analyses allow us to unambiguously identify the DA2/AMP and DL PCs and the derived DA2, DA3 and DO5 FCs and AMP (Enriquez et al., 2012; Figure 1A and Figure 3— figure supplement 1, Video 7). In early stage 10 embryos, the first selected, DA2/AMP PC is recognizable as a large apical cell, expressing high Nau levels (Figure 3B,B’). At stage 11, after the DA2/AMP PC has divided, the DA3/DO5 PC is observed, adjacent to the DA2 FC (Figure 3C). 3-D analyses also revealed previously undescribed, low level Nau expression in two or three cells surrounding each PC being selected (Figure 3B,F; Figure 3—figure supplement 2). This Nau expression pattern was reminiscent of subgroups of PMCs cells displaying higher level dpMAPK (di-phospho mitogen-associated protein kinase), diagnostic of EGFR activity (Carmena et al., 1998, 2002) and postulated to be cells primed to become PCs. Double staining confirmed that the Nau and dpMAPK patterns overlap, revealing that low level Nau expression corresponds to cells transitioning from PMC to PC, before reaching high level in selected PCs (Figure 3—figure supplement 2). Using Nau staining allowed us to follow these cells and PCs in subsequent FISH experiments.

Video 7. Multiple FCs originate from the Col-expressing PMC.

Figure 3. aop and edl differential expression and roles during PC selection.

(A) Schematic representation of the positions of DL PCs and FCs, relative to the A/P, D/V and proximal/distal axes in stage 10, 11 and 12 wt embryos (Video 7); the blue trapeziums indicate planes of section shown in panels (B–K) and (R–U); Col expression is in red. (B–I) ISH to aop (B–E) and edl (F–I) primary transcripts (red dots), in wt embryos stained for Col (blue) and Nau (green), at stages indicated above; early stage is abbreviated ste; two different planes of the same embryo are shown in B and B’, F and F’. aop transcription in the Col PMC (B), and the AMP (D). (F–I) edl transcription in all PCs, the AMP and the DA3 FC. (B,F) Nau accumulation in two to three Col PMC cells, below the emerging PC. (J,O) 3D reconstruction of the Col PMC during DA2/AMP and DA3/DO5 PC selection; Col staining, red, Nau, green. The embryonic stage indicated in each panel. (J, K) wt; (J) apical DA2/AMP PC (dotted white circle); (K) apical DA3/DO5 PC (dotted circle), DA2 FC and AMP (asterisks). (L, M) aop embryos; (L) premature DA3/DO5 PC selection; additional Nau-expressing PMC cells (arrow), become PCs, (M). (N, O) edl embryos; (N) no PC is selected; a group of 3 to 4 Nau-expressing cells is embedded in the Col PMC; (O) two PCs are simultaneously selected. (P–U) ISH to col primary transcripts (red), Nau staining (green); (P–R) wt; sequential col transcription in the PMC and DA2/AMP PC (P), DA3/DO5 PC (Q), and DA3 FC (R). (S) aop mutant: simultaneous col transcription in two apical PCs; increased number of low level Nau-expressing cells (green dotted circle). (T,U) edl mutant; ectopic col transcription in the DA2/AMP PC (T) and DA2 FC (U). (V) Measurement of the diameter of Col (red) and Nau (green) expressing domains in early stage 10 wt and aop embryos. The Col expression domain is identical (P value = 0,1410; ns) and Nau domain expanded in aop compared to wt (P value<0,0001; ****), schematized on top of the statistics. Bars: 5 μm

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Snapshot for Video 7.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Transient Nau expression in subsets of PMC cells.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. Extended analysis of the aop muscle mutant phenotype.

aop and edl activities control sequential DA2/AMP and DA3/DO5 PC selection

FISH experiments indicated aop transcription in Col PMC cells (Figure 3B), but not PCs (Figure 3B’–E), indicating its repression during the PC selection process, consistent with a role in promoting FCM fate (Carmena et al., 2002) and being a target of the FCM TF Lameduck (Ciglar et al., 2014). Conversely, edl transcription was not detected in PMC cells, but in PCs and the dorsal AMP and DA3 FC (Figure 3F–I). Thus aop and edl show sequential, complementary transcription patterns. In stage 10 aop mutant embryos, col transcription was detected in PMC cells as in wt (Figure 3P,S and V). However, a significantly increased number of cells expressing low Nau level revealed that aop down-regulation of EGF-R signaling was required to restrict Nau expression to PMC cells primed to become PCs (Figure 3P,S,V). Furthermore, 3-D reconstructions confirmed the presence of two apical cells expressing high Nau Level (21/27 PMCs with 2, and 6/27 with 1 apical PC), when only the DA2/AMP PC was observed in wt (30/35 PMC with 1 apical PC and 5/35 with no apical PC; Figure 3J,L). Thus, concomitant, early selection of two PCs in aop embryos prefigures the DA3>DA2 transformation (Figure 2T). At stage 11, Nau remained expressed at high level in several cells, showing that supplementary PMC cells are primed to become PCs (Figure 3M, compare to). This corroborates the observation of several aligned DA3-like fibers revealed by phalloidin staining of stage 16 aop mutant embryos (Figure 3—figure supplement 3). Conversely, in edl mutant embryos, no high Nau-expressing apical cell was observed at stage 10 (30/37 segments), when the DA2/AMP PC is selected in wt embryos. Rather, three to four small low Nau-positive cells remained embedded in the Col PMC (Figure 3N compare with Figure 3J) (Figure 3O compare to Figure 3K) both of which transcribed col (Figure 3T compare with Figure 3Q). Accordingly, col transcription was maintained in two cells at late stage 11, at positions corresponding to DA2 and DA3 FCs in wt embryos (Figure 3U compare with Figure 3R). In summary, we found that sequential PC selection is inversely compromised in aop and edl mutants. In absence of aop, the DA3/DO5, and supernumerary PCs are selected early, and in absence of edl, the DA2/AMP is selected too late.

We have previously shown that the time lag between DA2/AMP and DA3/DO5 PC selection coincided with a period of dorsal regression of Tin expression, such that only the first selected, DA2/AMP PC inherited Tin (Boukhatmi et al., 2012; Figure 4C–D'). Tin staining of aop mutant embryos showed that the two apical cells observed at stage 10 inherit Tin (Figure 4E,E'), confirming advanced selection of the DA3/DO5 PC. Conversely, in edl mutants, none of the apical cells inherited Tin, confirming a delayed selection of the DA2/AMP PC (Figure 4G,H'), consistent with both transcribing col (Figure 3T,U). To verify that the observed shifts in PC selection timing lead to shifts of PC identity, we analyzed tup transcription. As previously shown, only the DA2/AMP PC inherits Tin levels above the threshold required for tup activation (Figure 4I), leading in turn to col repression and initiation of tup auto-regulation (Boukhatmi et al., 2012). We found that, in aop mutants, early selected PCs transcribed tup (Figure 4J), while in edl mutants, late selected PCs did not (Figure 4K), mirroring col transcription (Figure 3T,U). Together, Tin, tup and col expression data, and the DA3>DA2 and DA2>DA3 muscle transformations predominantly observed in aop and edl embryos, respectively, show that timely PC selection is essential for each PC to inherit different Tin levels and either initiate tup (DA2/AMP) or col (DA3/DO5) feed-forward positive loops. Positive auto-regulation, a hallmark of bistable systems (Graham et al., 2010; Park et al., 2012), of either tup or col distinguishes between DA2 and DA3 identities (Boukhatmi et al., 2012; Figure 4L).

Figure 4. aop and edl control the temporal sequence of PC selection.

(A,B) Schematic representation of the DA2/AMP PC and FCs and DA3/DO5 PC, at stages 10 (A) and 11 (B); the blue trapeziums indicate the planes of section shown below. (C–H’) Tin (green) and Col (red) embryo staining. (C, C’) Tin expression in the DA2/AMP PC and underlying PMC cells. (D, D’) Tin expression has regressed dorsally; the DA3/DO5 PC and underlying PMC cells are Tin negative. (E–F’) aop mutants; (E, E’), stage 10, two Col and Tin-expressing PCs are selected; (F, F’) stage 11, Col positive, Tin-negative cells are selected. (G–H’) edl mutants; (G, G’), No PC is selected. (H, H’) Two PCs are selected after dorsal regression of Tin expression. (I–K) FISH to tup primary transcripts in wt (I) aop (J) and edl (K) stage 10 (I, J) and 11 (K) embryos, stained for Col (blue) and Nau (green). In wt embryos (I) tup expression is only detected in the first selected Col positive PC (DA2/AMP, 100% n = 27). In aop mutants (J), tup transcription is sometimes detected (17% n = 34) in a second Col positive PC (arrow). In edl mutants (K), tup transcription is frequently lost in Col positive PCs (82% n = 29). (L) Summary scheme of the aop and edl phenotypes; wt, late stage (stl) 10; only the first-born, DA2/AMP PC inherits Tin, and activates tup, preventing Col autoregulation (left) which occurs in the second born, DA3/DO5 PC, in absence of Tin and Tup, stage 11 (Boukhatmi et al., 2012). In edl and aop mutants, the temporal sequence of PC selection is compromised; it occurs too early and too late in aop and edl mutants, respectively, leading to confusions of DA2 and DA3 fates. Bars: 10 μm

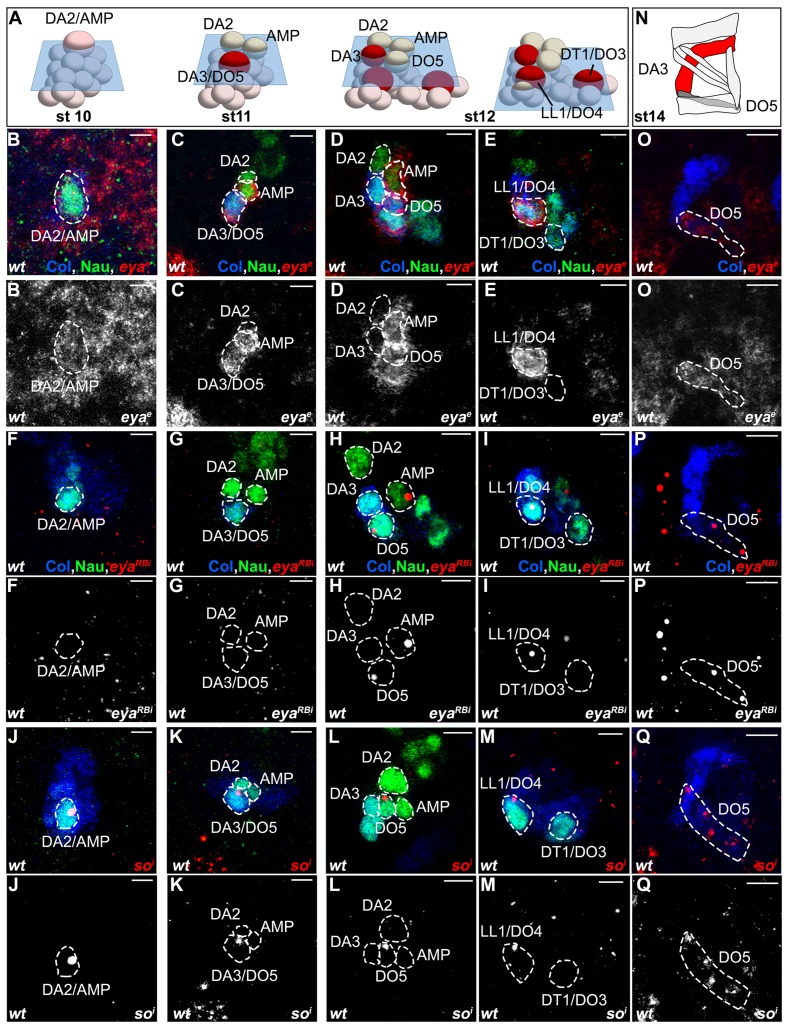

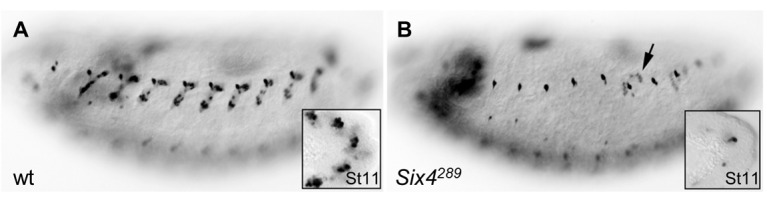

eya and so act sequentially in specifying DA3 and DO5 identity

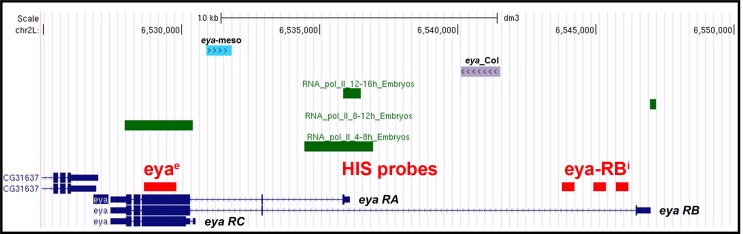

Drosophila eya gives rise to 3 different mRNA and protein isoforms (eya-RA, eya-RB, eya-RC) corresponding to the alternate use of different Transcription Start Sites (TSS) (Flybase FBgn0000320; Figure 5—figure supplement 1). FISH performed with a probe complementary to a common coding region, eyae, detected eya expression in the Col PMC, DA2/AMP, DA3/DO5 and LL1/DO4 PCs and DO5 lineage (Figure 5B–E,O and Figure 5— figure supplement 2). However, an intronic probe specific for transcripts initiated from the 5’-most TSS (eya-RBi; Figure 5—figure supplement 1) revealed that eya-RB transcription was restricted to the AMP, DO5 FC/muscle and the LL1/DO4 PC (Figure 5F–I,P and Figure 5— figure supplement 2), implying that, conversely, eya-RA/RC is specifically expressed in the PMC, the DA2/AMP and the DA3/DO5 PCs. This indicated a temporal shift in TSS, leading to sequential production of different Eya protein isoforms. In eya mutants, col transcription was detected in PMC cells like in wt (not shown), but prematurely lost in the DA3/DO5 PC, and undetectable in the DA3 FC (Figure 5R,S), showing that eya-RA/RC is required for sustained col transcription during PC specification. Reciprocally, both eya-RA/RC transcripts in the DA3/DO5 PC (de Taffin et al., 2015) and eya-RB transcripts in the DO5 FC (Figure 5T,U) were lost in col mutants, revealing that Eya and Col positively regulate each other transcription. Whether, both eya-RA/RC, and eya-RB are under direct control of Col binding to a dedicated cis-regulatory module (CRM) (de Taffin et al., 2015; Figure 5—figure supplement 1), or eya-RB control is indirect, and requires prior expression of eya-RA/RC at the PC stage (Figure 5X), remains unknown.

Figure 5. Sequential eya and so transcription and control of col transcription in distinct muscle lineages.

(A) Schematic representation of the positions of DL PCs and FCs in stage 10, 11 and 12 wt embryos, reproduced from Figure 3A; the blue trapeziums indicate the planes of section shown below, panels (B–M). (B–M and O–Q) ISH to eya and so transcripts (red) in wt embryos stained for Col (blue) and Nau (green). (B–E), eya expression in the DA2/AMP (B), DA3/DO5 (C) AMP and DO5 FC (D) LL1/DO3 PC (E). (N) Schematic representation of the DL muscle pattern, DA3 in red and DO5 in grey. (O) DO5 eya expression. (F–I) eya-RB transcription in the AMP DO5 FC (H) and LL1/DO4 PC (I). (P) DO5 eya-RB transcription. (J–M, Q) so transcription in the DA2/AMP, DA3/DO5 and LL1/DO4 PCs, DO5 FC and muscle. (R,S) Loss of col transcription in the DA3/DO5 PC in eya mutants. (T–U) Loss of eya-RB transcription in col mutants (U). (V,W) col ectopic transcription in the DO5 FC in so mutants. Embryos in R-W are co-stained for Nau (green). (X) Summary diagram of eya and so expression and function in DL muscle lineages. Bars: 5 μm

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Schematic representation of the eya genomic region and transcripts.

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. Sequential eya and so transcription.

Figure 5—figure supplement 3. Loss of DA3 Col expression in Six4 mutant embryos.

Eya protein phosphatases interact with Six family TFs, Six4, Optix (Op) and So in Drosophila (see introduction). We found that so was transcribed in the DA2/AMP, DA3/DO5 and LL1/DO4 PCs and subsequently maintained only in the DO5 FC and muscle (Figure 5J–M, Q and Figure 5— figure supplement 2). col transcription in DL PCs was normal in so mutants, showing that So is not required for Eya-RA/RC regulation of col transcription (not shown). On the contrary, col was ectopically transcribed in the DO5 FC (Figure 5V,W), showing that so activity contributes to repress col transcription in this lineage. so transcription in the DO5 FC and contribution to distinguishing between the DA3 and DO5 identities suggests that so could act downstream of N in this process (Crozatier and Vincent, 1999). The difference between the eya and so DA3 mutant phenotypes (Figure 2D,F, Figure 2—figure supplement 2, and Videos 4 and 6) suggested that eya was partnering with Six4 to positively regulate col. To verify this assertion, we analyzed DA3 Col expression in Six4 mutants. The loss of Col expression (Figure 5—figure supplement 3), very similar to that observed in eya mutants (Figure 2D), supports the conclusion that Eya partners with Six4 to positively, and with So to negatively regulate col. Thus, Six4 and So play distinct roles during muscle specification (Figure 5X).

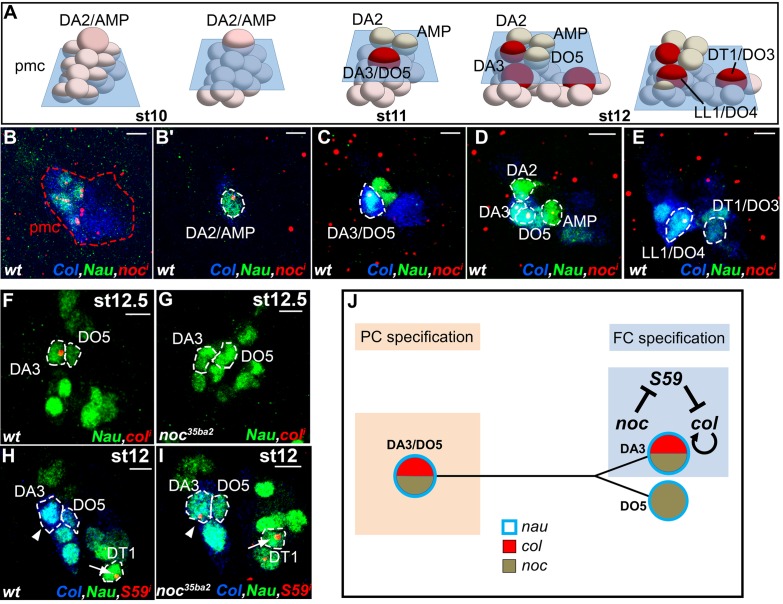

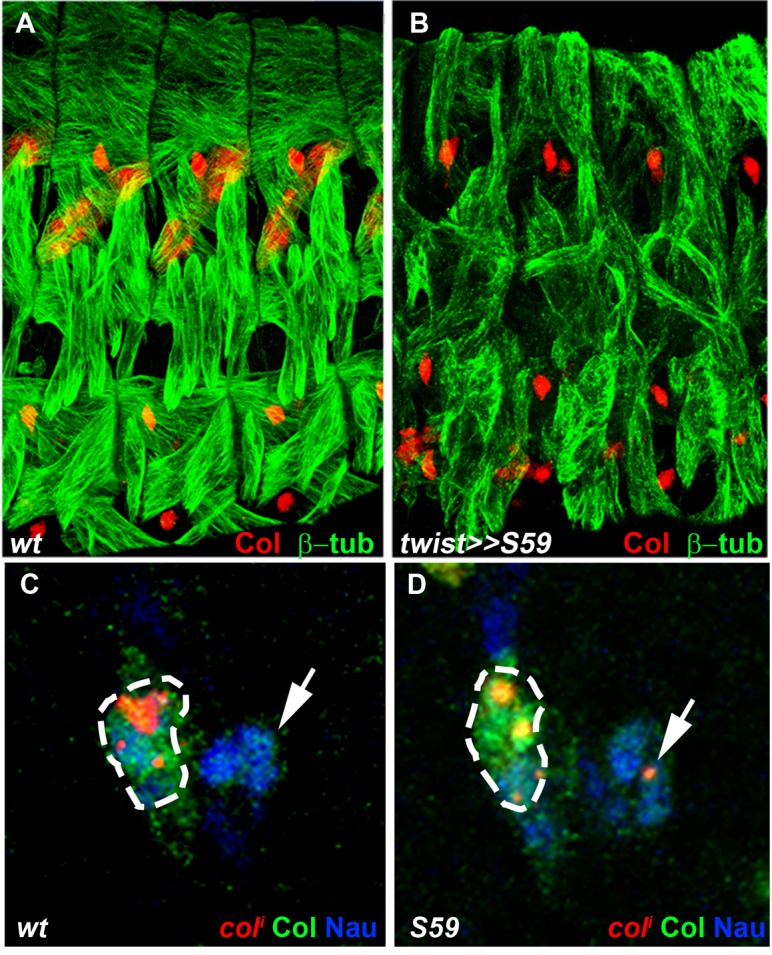

Positional information; noc distinguishes between DA3 and DT1 identity

noc is required for DA3 Col expression and DA3 formation (Figure 2). noc and its paralog elbow (elb), act as transcription repressors in morphogenesis of appendages, tracheal branches and specification of monochromatic receptors in the retina (Dorfman et al., 2002; Nakamura et al., 2004; Wernet et al., 2014) but a function in myogenesis was not reported. A deficiency removing elb (Df(2R)exel6035) had no DL muscle phenotype, while the phenotypes of noc35ba2 mutants and a deficiency removing both elb and noc were identical (Figure 1—source data 1 and Figure 2E). Thus, only noc is required for DL muscle specification. FISH experiments revealed noc transcription in Col PMC cells which express low Nau level, followed by the DA2/AMP, the DA3/DO5 and the LL1/DO4, but not the DT1/DO3 PC (Figure 6B–E). In noc mutants, col transcription was detected in the PMC and DA3/DO5 PC (not shown) but completely lost from the DA3 FC (Figure 6F,G), correlating with the loss of Col DA3 expression after the PC stage (Figure 2E,K). The DA3>DT1 transformation observed at stage 15 in noc mutants (Figure 2Q) was therefore intriguing, since a DA3>DA2 identity shift was observed in other mutants where DA3 Col expression was lost, namely col, eya and Six4 (Figure 2D and Figure 5—figure supplement 3). Since DT1 identity requires S59 expression in the DT1 FC (Knirr et al., 1999), we analyzed S59 expression in noc mutant embryos and found that it was ectopically expressed in the DA3 FC (Figure 6H,I), consistent with DA3>DT1 transformation. This finding suggested that loss of DA3 Col expression in noc embryos was secondary to gain of S59 expression. To test this possibility, we expressed S59 in all myoblasts, using the Twist-Gal4 pan-mesodermal driver. While the muscle pattern was severely disorganized, loss of Col expression in Twi>S59 embryos demonstrated S59 ability to repress col mesodermal expression (Figure 6—figure supplement 1A,B). We next analyzed col transcription in S59 mutants and found that it was ectopically transcribed in one posterior DL FC, likely DT1 (Figure 6—figure supplement 1C,D). On the one hand, these data confirmed that S59 represses col transcription in the DT1 lineage, via an incoherent feed-forward loop initiated by Col activation of S59 in the DT1/DO3 PC (Enriquez et al., 2012). On the other hand, noc and S59 loss-of-function and S59 gain-of-function data revealed a double negative regulatory cascade where noc repression of S59 maintains col transcription in the DA3 lineage and DA3 identity (Figure 6J). Noc expression in the DA3/DO5 PC and not the DT1/DO3 PC (Figure 6E) thus distinguishes between DA3 and DT1 identities (Figure 7).

Figure 6. noc transcription and control of col and S59 transcription in DL muscle lineages.

(A) Relative positions of DL PCs and FCs between stages 10 and 12, reproduced from Figure 3A; the blue trapeziums indicate the planes of section shown below, panels (B–E). (B–E), Embryos co-stained for Nau (green) and Col (blue); (B) noc transcription (red) in a small subset of Col PMC cells expressing low Nau level (B), the DA2/AMP (B’), DA3/DO5 and DA3 and DO5 FCs (C,D) and LL1/DO4 but not the DT1/DO3 PC (E). (F–I) Embryos stained for Nau (green) and (H,I) Col (blue). (F, G) loss of col transcription in the DA3 FC (red dots) in noc mutants. (H) wt S59 transcription in DT1 (red dots, arrow) and (I) ectopic transcription in the DA3 FC (arrowhead) in noc mutant embryos. (J) Summary diagram of noc expression and function in DL muscle lineages. Bars: 5 μm

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. S59 represses col transcription.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. eya and noc are required for Kr expression in the LL1 FC.

Figure 7. Intertwined transcriptional control of DL muscle identity: A progressive resolution of the possible.

Diagrammatic representation of transcription regulatory interactions and loops operating in DL muscle identity specification. One abdominal segment is considered. 3 steps are indicated on top and color-shaded. Left, PC selection; the A/P axis is on the abscissa and the developmental time on the ordinate. aop and edl positively and negative regulate Nau expression (blue circle) in a subset of PMC cells, favoring and inhibiting selection of PCs from PMC cells, respectively. Center, PC specification: the dorsal DA2/AMP and dorso-lateral DA3/DO5, LL1/DO4 and DT1/DO3 PCs are represented. Right, FC specification; only the DA3 and DO5 lineages are detailed. Color coding of expression of the different iTFs, and the names of their vertebrate orthologs are indicated. Genes and either positive (arrow), or negative (crossed line) regulatory steps identified in this study are drawn in black; previously reported interactions are in grey.

Analysis of the DL muscle phenotypes showed that formation of the LL1 muscle is also affected in noc, aop and eya mutants (Figure 2K,W and Figure 2—source data 1). Kr was previously shown to be expressed in the LL1 PC and required for LL1 development (Ruiz-Gomez et al., 1997). We found that Kr expression in the LL1/DO4 (but not DA1) PC required both noc and eya activity, but neither aop nor col (Figure 6—figure supplement 2) (Enriquez et al., 2012). These data further underline the intricate wiring and combinatorial nature of transcriptional regulations specifying muscle identities (Figure 7).

Discussion

A 3-steps model of muscle identity specification has been put forward 18 years ago in Drosophila, based on a limited repertoire of muscle iTFs (Carmena et al., 1998). In this work, we took an unbiased genetic approach and focused on a small group of muscles, to identify new transcription regulators of muscle identity. By combining functional and expression analyses of these new iTFs at the primary transcripts level, with previous data, we propose a novel, dynamic view of the transcriptional control of muscle identity by evolutionarily conserved TFs.

Noc, a new iTF responding to multimodal information

Noc and Elb are two transcription repressors belonging to the NET family of C2H2 zinc finger proteins (Dorfman et al., 2002; Nakamura et al., 2004). Until now, identification of a Tin-dependent mesodermal noc enhancer was the only suggestion of a possible function in muscle development (Jin et al., 2013). We show here that noc is required for distinguishing between DA3 and DT1 muscle identities. Primary transcript analyses revealed that noc maintenance of col transcription in the DA3 lineage involved a double Noc —|S59 —|col negative loop. Col activation of S59 expression (Enriquez et al., 2012) initiates a negative, 'incoherent' feed-forward loop in the DT1/DO3 PC, resulting in Col repression and DT1 identity. Noc breaks this loop in the DA3 lineage (Figure 7). noc is transcribed in myoblasts expressing low Nau level whose number is controlled by EGF-R signaling, and selected PCs (Figure 6 and Figure 3—figure supplement 2). However, it is not transcribed in the DT1/DO3 PC which is specified under control of abdominal Hox proteins (Enriquez et al., 2010). Thus noc regulation integrates multimodal signaling and positional inputs. Functions of vertebrate NET proteins Nolz-1/Nolz2 and ZNF503/nlz1 have, so far, been addressed in the central nervous system. Yet, zebrafish Znf503 and mouse nolz1 are expressed in branchial arches (zfin ID: ZDB-Gene-031113-5, genebank accession number NM-198840; Chang et al., 2013). Whether this expression corresponds to migrating myoblasts which contribute to facial muscle development and express orthologs of other iTFs studied here (Nathan et al., 2008; Sambasivan et al., 2009; Tolkin and Christiaen, 2012; Razy-Krajka et al., 2014; Diogo et al., 2015), remains to be explored.

Temporal control of muscle PC selection

Our previous finding that several PCs are sequentially selected from the Col PMC and each express a specific iTF code brought to light the importance of time in muscle identity specification (Boukhatmi et al., 2012). We report here that aop and edl, are required for the robustness of sequential selection of the DA2/AMP and DA3/DO5 PCs. A consequence of lack of Aop function is the premature, concomitant selection of several Nau-expressing PCs, when sequential in wt embryos. These data indicate that Aop acts to restrict EGF-R MAPK activity to prospective PCs, as previously suggested (Carmena et al., 2002). Inversely, edl expression in selected cells and delayed PC delamination in edl mutant embryos indicate that Edl ensures timely progression of primed cells to a stable PC fate. Thus, proper regulation of EGF-R signaling effectors is both required for the proper number and temporal sequence of PC selections. During eye development, the differentiation of all ommatidial cell types is triggered in a stereotypical sequence by reiterated EGFR use (Freeman, 1996). Likewise, EGF-R signalling regulates pulses of cell delamination from the ectoderm (Brodu et al., 2004). Whether pulses of EGF-R signalling control serial PC selection remains to be determined. Parallels between serial PC selection and successive waves of neuroblast (NB) selection (Doe, 1992; Berger et al., 2001) are striking. However, in NB lineages, the focus of investigation has shifted to the sequential expression of Temporal Transcription Factors (TTFs) in each NB progeny, which specifies the temporal identity of neurons (Isshiki et al., 2001), and how birth time controls NB identity has not been determined.

Nau expression in early steps of myogenesis. A new Nau function?

Our observation of an increased number of Nau-positive cells in aop mutants revealed that Nau/MyoD is expressed in myoblasts primed to a PC fate. Nau role in generic myogenesis versus identity aspects has been debated (Balagopalan et al., 2001; Wei et al., 2007). We have previously proposed that Nau iTF functions could reflect lineage-dependent cooperation with other iTFs (Enriquez et al., 2012). Another b-HLH protein, Lethal of Scute (L(1)sc), has been proposed to act as a promuscular gene (Carmena et al., 1995), based on its pattern of expression and regulation in PMCs and PCs, and by analogy to the role of proneural b-HLH proteins in NB selection. Yet, only minor muscle patterning defects were observed in l(1)sc mutants (Carmena et al., 1995). The detection of Nau expression in PMC cells subject to high EGF-R signaling raises the possibility that Nau could play earlier functions than previously thought in the PC specification process.

Translation of developmental time into muscle identity

The time lag between DA2/AMP and DA3/DO5 PC emergence coincides with dorsal regression of Tin expression, due to an auto-regulatory circuit in which Tin progressively limits its own transcription (Johnson et al., 2011). We previously showed that only the DA2/AMP PC inherited Tin (Boukhatmi et al., 2012). Considering Tin levels as a translation of developmental time, our new results show that EGF-R control of serial PC selection converts this translation into sharp transcriptional decisions and ultimately distinct muscle identities (Figures 4 and 7). Tup and Col direct up-regulation of their own transcription after the PC stage (Enriquez et al., 2010; Boukhatmi et al., 2012, 2014) can explain why small differences in initial expression levels are transformed into stable muscle fates. Our data thus provide a new paradigm for how birth timing controls cell identity during development (Figure 4L).

Different Eya isoforms and Six partners are sequentially involved in muscle development

Drosophila Six proteins, Six4, So and Op correspond to vertebrate Six1/2, Six4/5 and Six3/6, respectively (Kenyon et al., 2005). Six1/2/4/5 proteins have been reported to interact with eya in controlling the myogenic progenitor cell population in mouse, while no role was found for Six3/6 in this process (Relaix et al., 2013). Likewise, we did not observe DL muscle pattern defects in embryos lacking op (Df(2R)Exel6055). Drosophila Six4 was previously proposed to interact with Eya in regulating somatic muscle development, both genes showing similar expression pattern (Clark et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2009). Tin in vivo binding to the so locus (Liu et al., 2009; Jin et al., 2013) raised the possibility that so could also be involved in muscle development. Interestingly, temporal ChIP profiles indicated Tin binding to six4 earlier than to so (Jin et al., 2013), suggesting sequential regulation. Our data show that one eya isoform, eya-RB, is transcribed later than the other isoforms (eya-RA/RC, Figure 5—figure supplement 1), owing to a switch in TSS, correlating with the profile of in vivo RNA polymerase II binding (Bonn et al., 2012). Together, these expression data and our finding that eya and Six4 regulate positively, and so negatively, col transcription, suggest that Eya could switch from activator to repressor, by changing partner, from Six4 to So. We thus hypothesize that sequential partnering of different Eya isoforms and Six proteins could contribute the diversity of iTF codes and muscle morphologies (Figure 7). Various contributions of mouse Six1/2/4 to the Pax3/MyoD transcription regulatory network controlling early myogenesis in different embryonic territories have recently been reported (Relaix et al., 2013). It would be interesting to determine whether different eya isoforms are also involved in different Six partnerships and control different facets of muscle development in vertebrates.

An integrated view of the transcriptional control of muscle identity

Characterisation of aop, edl, eya, noc and so functions and transcription dynamics revealed that distinguishing between DA3, versus DA2, DT1 or DO5 identities involves specific sequences of transcriptional regulations integrating temporal and positional cues (Figure 7). The functions of these, and previously characterized iTFs, underline the intricacy of positive and negative regulatory loops acting at successive steps in different muscle lineages (Figure 7). Besides clear transformations suggestive of complete identity switch, a significant fraction of muscles show incomplete transformations in iTF mutant embryos. This supports the idea that, rather than lineage-specific 'master iTFs', stereotypy of Drosophila muscle patterns relies upon combinatorial inputs of multiple iTFs during PC and FC specification. The finding that TFs combinatorically specify muscle identity (Enriquez et al., 2012; de Joussineau et al., 2012; Boukhatmi et al., 2014, this report) indicates that activation of their target genes is context-dependent and involves multiple cis-regulatory elements. Multiple levels of cross-regulation (Figure 7) could provide robustness to the final muscle pattern.

While a function of Nolz proteins in the mesoderm remains to be investigated, Nkx2.5, Eya, Six1, Islet1, Col/Ebf and MyoD, are core components of transcriptional regulatory networks controlling the development of pharyngeal/facial muscles originating from the cardio-pharyngeal territory in chordates. Our data raise the possibility that these conserved mesodermal TFs could combinatorically control muscle regional diversity in vertebrates, attested by human muscular dystrophies (Emery, 2002). but whose molecular basis remains poorly understood. It is reasonable to speculate that these TFs have been co-opted in different wirings during evolution to generate the muscle lineage diversity found in the animal kingdom.

Materials and methods

Screening procedure and mutant alleles

Deficiency lines from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center were balanced over a CyO–wg–LacZ chromosome to genotype embryos (Chanut-Delalande et al., 2014). Screening for embryonic phenotypes was as in Chanut-Delalande et al. (2014), except that embryos were stained with a monoclonal mouse antibody against the Col protein (Dubois et al., 2007). Genetic complementation assays were used to identify genes in chromosomal deficiencies whose loss led to DA3 phenotype. Homozygous aop1, edlL19, eyaCII/IID, so3, noc35ba2, salm1, and col1 homozygous mutants showed muscle phenotypes identical to trans-heterozygous mutants over deficiency. They were thus considered as null alleles and consistently used for phenotypic analyses. For eya analysis, we used eyaCII/IID/Df(2l)BSC354 trans-heterozygous embryos as eyaCII/IID homozygous embryos present a strong myoblast fusion defect (not shown), not observed in transheterozygous and probably due to a secondary mutations on the eyaCII/IID chromosome. Col::moeGFP expression under control of a late mesodermal col CRM (colLCRM; previously named 2.6_0.9c; Dubois et al., 2007) was used to visualize the DA3 muscle contours in mutant embryos. The col PMC cells and PCs were visualized in col mutant embryos by LacZ expression under control of the early mesodermal col CRM, colECRM (previously CRM276; Enriquez et al., 2010). For all deficiency screening, sample size was estimated empirically (>100 stage 14–16 embryos, in duplicates). For aop, edl, eya, so, and noc, mutant analyses, sample sizes are indicated in the text and the legend of Figure 2—source data 1.

Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization and imaging

Antibody staining and in situ hybridization with intronic probes were as described previously (Dubois et al., 2007). Primary antibodies were: mouse βPS integrin, anti-Col (Dubois et al., 2007), anti-GFP (Torrey Pines Biolabs), anti-β-galactosidase (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin), rabbit anti-Tin (Manfred Frasch, Erlangen, Germany), anti-Nau (Bruce Paterson, Bethesda, USA), anti-Kr (Ralf Pflanz, Goettingen, Germany), anti-β3-tubulin (Renate Renkawitz-Pohl, Marburg, Germany). Secondary antibodies were: Alexa Fluor 488- and 555-conjugated antibodies (Molecular Probes), and biotinylated goat anti-mouse (Vector Laboratories). Digoxygenin-labelled antisense RNA probes were transcribed in vitro from PCR-amplified DNA sequences, using T7 polymerase (Roche Digoxigenin labelling Kit). For aop, edl and eya-RB, 3 non overlapping 600 nucleotide (nt) probes were pooled together; for noc, a single probe spanning the entire 302 bp intron; for so, a 2771nt probe hydrolyzed to ~600nt fragments (Cox et al., 1984). The primer pairs used to amplify the different intron fragments are listed below, with the T7 promoter indicated by small characters.

aop1: CTCATTGTATGCACGGTACG

aop1T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggATAGCTGCGGCAGAAGCAGG

aop2: GCAACAGCAACACTCCAATC

aop2T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggAGACGGTGCGGGCAGAAATTGGG

aop3: AAGAGAAAGAGCACGGCAAG

aop3T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggAGATCGGCGACGTTCTCCGAGAC

edl1: GGGAGGTGGAAATGACAAAC

edl1T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggCATCGTCTGCCTGACGTCTG

edl2: CCAAATATCGCCGATAAGCC

edl2T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggAGACTGCGCACAGGATGCACACC

edl3: GAAGATCGACCAGACTTAGG

edl3T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggAGAAGCGGCGTCGAGATTCCCAG

eyaRB1: GTTCCTCTAGCTCCGAAATG

eyaRB1T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggTTACGCCGGAGTTGTGAGGG

eyaRB2: GACAGCATCGGAGACAACAC

eyaRB2T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggCCCGGCCACAAACGAGAAAC

eyaRB3: AGCCCAGTCAAATGCGAAAC

eyaRB3T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggATGCGTGTCCGTGTCGCTAC

noc1: CGACGGTTAGTATTGACTAAG

noc1T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggGGCGTCCATCTGTTATGAATAAAATG

so1: TCCACGTTTCCAAGTTGGCTACTC

so1T7: ccgaattctaatacgactcactatagggAATGCGGCATGTTCGATGCTCGATAATCGG

Confocal sections were acquired on Leica SP5 or SPE microscopes at 40× magnification, 1024/1024 pixel resolution. Images were assembled using ImageJ and Photoshop softwares. 3-D reconstructions of the topology of DL PCs and FCs were made from optimized section, 'using volocity (PerkinElmer) or Imaris (Bitplane) Softwares'. Images presented are representative of observations of at least 10 embryos per genotype at a given stage and between five and six segments per embryo. To compare the size of the Col and Nau expression domains in wt and aop mutants, optimized stacks of double-stained embryos in the same orientation were flattened, and the largest diameter of each domain measured. Statistical analysis was with GraphPad Prism5 using unpaired t-test.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Bloomington Stock Center and colleagues for Drosophila strains and Manfred Frasch, Bruce Paterson, Ralf Pflanz, Renate Renkawitz-Pohl for antibodies. We acknowledge Laetitia Bataillé, Hadi Boukhatmi, Véronique Brodu, Alice Davy and Jean-Antoine Lepesant for hepful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript and the help of Brice Ronsin, Toulouse RIO Imaging platform, and Julien Favier for maintenance of fly stocks.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique to Laurence Dubois, Jean-Louis Frendo, Hélène Chanut, Michèle Crozatier, Alain Vincent.

Ministère de l'Éducation Nationale to Laurence Dubois, Jean-Louis Frendo, Hélène Chanut, Michèle Crozatier, Alain Vincent.

AFM-Téléthon 14895-SR to Laurence Dubois, Jean-Louis Frendo.

Agence Nationale de la Recherche 13-BSVE2-0010 to Alain Vincent.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Author contributions

LD, Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

J-LF, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

HC-D, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Contributed unpublished essential data or reagents.

MC, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article, Contributed unpublished essential data or reagents.

AV, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

References

- Baker DA, Mille-Baker B, Wainwright SM, Ish-Horowicz D, Dibb NJ. Mae mediates MAP kinase phosphorylation of Ets transcription factors in Drosophila. Nature. 2001;411:330–334. doi: 10.1038/35077122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopalan L, Keller CA, Abmayr SM. Loss-of-function mutations reveal that the Drosophila nautilus gene is not essential for embryonic myogenesis or viability. Developmental Biology. 2001;231:374–382. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate M. The mesoderm and its derivatives. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The Development of Drosophila Melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 1013–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Baylies MK, Bate M, Ruiz Gomez M. Myogenesis: a view from Drosophila. Cell. 1998;93:921–927. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger C, Urban J, Technau GM. Stage-specific inductive signals in the Drosophila neuroectoderm control the temporal sequence of neuroblast specification. Development. 2001;128:3243–3251. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.17.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn S, Zinzen RP, Girardot C, Gustafson EH, Perez-Gonzalez A, Delhomme N, Ghavi-Helm Y, Wilczyński B, Riddell A, Furlong EE. Tissue-specific analysis of chromatin state identifies temporal signatures of enhancer activity during embryonic development. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:148–156. doi: 10.1038/ng.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukhatmi H, Frendo JL, Enriquez J, Crozatier M, Dubois L, Vincent A. Tup/Islet1 integrates time and position to specify muscle identity in Drosophila. Development. 2012;139:3572–3582. doi: 10.1242/dev.083410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukhatmi H, Schaub C, Bataillé L, Reim I, Frendo JL, Frasch M, Vincent A. An Org-1-Tup transcriptional cascade reveals different types of alary muscles connecting internal organs in Drosophila. Development. 2014;141:3761–3771. doi: 10.1242/dev.111005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodu V, Elstob PR, Gould AP. EGF receptor signaling regulates pulses of cell delamination from the Drosophila ectoderm. Developmental Cell. 2004;7:885–895. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buff E, Carmena A, Gisselbrecht S, Jiménez F, Michelson AM. Signalling by the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor is required for the specification and diversification of embryonic muscle progenitors. Development. 1998;125:2075–2086. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena A, Bate M, Jiménez F. Lethal of scute, a proneural gene, participates in the specification of muscle progenitors during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes & Development. 1995;9:2373–2383. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena A, Buff E, Halfon MS, Gisselbrecht S, Jiménez F, Baylies MK, Michelson AM. Reciprocal regulatory interactions between the Notch and Ras signaling pathways in the Drosophila embryonic mesoderm. Developmental Biology. 2002;244:226–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena A, Gisselbrecht S, Harrison J, Jiménez F, Michelson AM. Combinatorial signaling codes for the progressive determination of cell fates in the Drosophila embryonic mesoderm. Genes & Development. 1998;12:3910–3922. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SL, Chen SY, Huang HH, Ko HA, Liu PT, Liu YC, Chen PH, Liu FC. Ectopic expression of nolz-1 in neural progenitors promotes cell cycle exit/premature neuronal differentiation accompanying with abnormal apoptosis in the developing mouse telencephalon. PLOS One. 2013;8:e14979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanut-Delalande H, Hashimoto Y, Pelissier-Monier A, Spokony R, Dib A, Kondo T, Bohère J, Niimi K, Latapie Y, Inagaki S, Dubois L, Valenti P, Polesello C, Kobayashi S, Moussian B, White KP, Plaza S, Kageyama Y, Payre F, A DIB. Pri peptides are mediators of ecdysone for the temporal control of development. Nature Cell Biology. 2014;16:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ncb3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah PY, Meng YB, Yang X, Kimbrell D, Ashburner M, Chia W. The Drosophila l(2)35Ba/nocA gene encodes a putative Zn finger protein involved in the development of the embryonic brain and the adult ocellar structures. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1994;14:1487–1499. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.2.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheyette BN, Green PJ, Martin K, Garren H, Hartenstein V, Zipursky SL. The Drosophila sine oculis locus encodes a homeodomain-containing protein required for the development of the entire visual system. Neuron. 1994;12:977–996. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciglar L, Girardot C, Wilczyński B, Braun M, Furlong EE. Coordinated repression and activation of two transcriptional programs stabilizes cell fate during myogenesis. Development. 2014;141:2633–2643. doi: 10.1242/dev.101956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark IB, Boyd J, Hamilton G, Finnegan DJ, Jarman AP. D-six4 plays a key role in patterning cell identities deriving from the Drosophila mesoderm. Developmental Biology. 2006;294:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozatier M, Vincent A. Requirement for the Drosophila COE transcription factor Collier in formation of an embryonic muscle: transcriptional response to notch signalling. Development. 1999;126:1495–1504. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.7.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin KD, Meinertzhagen IA, Wyman RJ. Basigin (EMMPRIN/CD147) interacts with integrin to affect cellular architecture. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118:2649–2660. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daburon V, Mella S, Plouhinec JL, Mazan S, Crozatier M, Vincent A. The metazoan history of the COE transcription factors. Selection of a variant HLH motif by mandatory inclusion of a duplicated exon in vertebrates. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2008;8:e14979. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Joussineau C, Bataillé L, Jagla T, Jagla K. Diversification of muscle types in Drosophila: upstream and downstream of identity genes. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2012;98:277–301. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386499-4.00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Taffin M, Carrier Y, Dubois L, Bataillé L, Painset A, Le Gras S, Jost B, Crozatier M, Vincent A. Genome-wide mapping of collier In vivo binding sites highlights Its hierarchical position in different transcription regulatory networks. PLOS One. 2015;10:e14979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo R, Kelly RG, Christiaen L, Levine M, Ziermann JM, Molnar JL, Noden DM, Tzahor E. A new heart for a new head in vertebrate cardiopharyngeal evolution. Nature. 2015;520:466–473. doi: 10.1038/nature14435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobi KC, Halfon MS, Baylies MK. Whole-genome analysis of muscle founder cells implicates the chromatin regulator Sin3A in muscle identity. Cell Reports. 2014;8:858–870. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe CQ. Molecular markers for identified neuroblasts and ganglion mother cells in the Drosophila central nervous system. Development. 1992;116:855–863. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrmann C, Azpiazu N, Frasch M. A new Drosophila homeo box gene is expressed in mesodermal precursor cells of distinct muscles during embryogenesis. Genes & Development. 1990;4:2098–2111. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman R, Glazer L, Weihe U, Wernet MF, Shilo BZ. Elbow and Noc define a family of zinc finger proteins controlling morphogenesis of specific tracheal branches. Development. 2002;129:3585–3596. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois L, Enriquez J, Daburon V, Crozet F, Lebreton G, Crozatier M, Vincent A. Collier transcription in a single Drosophila muscle lineage: the combinatorial control of muscle identity. Development. 2007;134:4347–4355. doi: 10.1242/dev.008409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois L, Vincent A. The COE--Collier/Olf1/EBF--transcription factors: structural conservation and diversity of developmental functions. Mechanisms of Development. 2001;108:3–12. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AEH. The muscular dystrophies. The Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez J, Boukhatmi H, Dubois L, Philippakis AA, Bulyk ML, Michelson AM, Crozatier M, Vincent A. Multi-step control of muscle diversity by Hox proteins in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 2010;137:457–466. doi: 10.1242/dev.045286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez J, de Taffin M, Crozatier M, Vincent A, Dubois L. Combinatorial coding of Drosophila muscle shape by Collier and Nautilus. Developmental Biology. 2012;363:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folker ES, Schulman VK, Baylies MK. Translocating myonuclei have distinct leading and lagging edges that require kinesin and dynein. Development. 2014;141:355–366. doi: 10.1242/dev.095612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 1996;87:651–660. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TG, Tabei SM, Dinner AR, Rebay I. Modeling bistable cell-fate choices in the Drosophila eye: qualitative and quantitative perspectives. Development. 2010;137:2265–2278. doi: 10.1242/dev.044826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon MS, Carmena A, Gisselbrecht S, Sackerson CM, Jiménez F, Baylies MK, Michelson AM. Ras pathway specificity is determined by the integration of multiple signal-activated and tissue-restricted transcription factors. Cell. 2000;103:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heanue TA, Reshef R, Davis RJ, Mardon G, Oliver G, Tomarev S, Lassar AB, Tabin CJ. Synergistic regulation of vertebrate muscle development by Dach2, Eya2, and Six1, homologs of genes required for Drosophila eye formation. Genes & Development. 1999;13:3231–3243. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein U, Rubin GM. Star is required in a subset of photoreceptor cells in the developing Drosophila retina and displays dosage sensitive interactions with rough. Developmental Biology. 1991;144:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isshiki T, Pearson B, Holbrook S, Doe CQ. Drosophila neuroblasts sequentially express transcription factors which specify the temporal identity of their neuronal progeny. Cell. 2001;106:511–521. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Stojnic R, Adryan B, Ozdemir A, Stathopoulos A, Frasch M. Genome-wide screens for in vivo Tinman binding sites identify cardiac enhancers with diverse functional architectures. PLOS Genetics. 2013;9:e14979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AN, Mokalled MH, Haden TN, Olson EN. JAK/Stat signaling regulates heart precursor diversification in Drosophila. Development. 2011;138:4627–4638. doi: 10.1242/dev.071464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon KL, Yang-Zhou D, Cai CQ, Tran S, Clouser C, Decene G, Ranade S, Pignoni F, C. Q CAI. Partner specificity is essential for proper function of the SIX-type homeodomain proteins Sine oculis and Optix during fly eye development. Developmental Biology. 2005;286:158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Jin P, Duan R, Chen EH. Mechanisms of myoblast fusion during muscle development. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2015;32:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knirr S, Azpiazu N, Frasch M. The role of the NK-homeobox gene slouch (S59) in somatic muscle patterning. Development. 1999;126:4525–4535. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leptin M, Bogaert T, Lehmann R, Wilcox M. The function of PS integrins during Drosophila embryogenesis. Cell. 1989;56:401–408. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YH, Jakobsen JS, Valentin G, Amarantos I, Gilmour DT, Furlong EE. A systematic analysis of Tinman function reveals Eya and JAK-STAT signaling as essential regulators of muscle development. Developmental Cell. 2009;16:280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson AM, Abmayr SM, Bate M, Arias AM, Maniatis T. Expression of a MyoD family member prefigures muscle pattern in Drosophila embryos. Genes & Development. 1990;4:2086–2097. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Runko AP, Sagerström CG. A novel subfamily of zinc finger genes involved in embryonic development. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2004;93:887–895. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan E, Monovich A, Tirosh-Finkel L, Harrelson Z, Rousso T, Rinon A, Harel I, Evans SM, Tzahor E. The contribution of Islet1-expressing splanchnic mesoderm cells to distinct branchiomeric muscles reveals significant heterogeneity in head muscle development. Development. 2008;135:647–657. doi: 10.1242/dev.007989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose A, Isshiki T, Takeichi M. Regional specification of muscle progenitors in Drosophila: the role of the msh homeobox gene. Development. 1998;125:215–223. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordan E, Brankatschk M, Dickson B, Schnorrer F, Volk T. Slit cleavage is essential for producing an active, stable, non-diffusible short-range signal that guides muscle migration. Development. 2015;142:1431–1436. doi: 10.1242/dev.119131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BO, Ahrends R, Teruel MN. Consecutive positive feedback loops create a bistable switch that controls preadipocyte-to-adipocyte conversion. Cell Reports. 2012;2:976–990. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignoni F, Hu B, Zavitz KH, Xiao J, Garrity PA, Zipursky SL. The eye-specification proteins So and Eya form a complex and regulate multiple steps in Drosophila eye development. Cell. 1997;91:881–891. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao F, Harada B, Song H, Whitelegge J, Courey AJ, Bowie JU. Mae inhibits Pointed-P2 transcriptional activity by blocking its MAPK docking site. The EMBO Journal. 2006;25:70–79. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razy-Krajka F, Lam K, Wang W, Stolfi A, Joly M, Bonneau R, Christiaen L, K LAM. Collier/OLF/EBF-dependent transcriptional dynamics control pharyngeal muscle specification from primed cardiopharyngeal progenitors. Developmental Cell. 2014;29:263–276. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebay I, Rubin GM. Yan functions as a general inhibitor of differentiation and is negatively regulated by activation of the Ras1/MAPK pathway. Cell. 1995;81:857–866. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Demignon J, Laclef C, Pujol J, Santolini M, Niro C, Lagha M, Rocancourt D, Buckingham M, Maire P. Six homeoproteins directly activate Myod expression in the gene regulatory networks that control early myogenesis. PLOS Genetics. 2013;9:e14979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Gómez M, Bate M, GOMEZ R. Segregation of myogenic lineages in Drosophila requires numb. Development. 1997;124:4857–4866. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gómez M, Romani S, Hartmann C, Jäckle H, Bate M. Specific muscle identities are regulated by Krüppel during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1997;124:3407–3414. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.17.3407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton E, Drysdale R, Abmayr SM, Michelson AM, Bate M. Mutations in a novel gene, myoblast city, provide evidence in support of the founder cell hypothesis for Drosophila muscle development. Development. 1995;121:1979–1988. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.7.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambasivan R, Gayraud-Morel B, Dumas G, Cimper C, Paisant S, Kelly RG, Kelly R, Tajbakhsh S. Distinct regulatory cascades govern extraocular and pharyngeal arch muscle progenitor cell fates. Developmental Cell. 2009;16:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorrer F, Dickson BJ. Muscle building; mechanisms of myotube guidance and attachment site selection. Developmental Cell. 2004;7:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serikaku MA, O'Tousa JE. sine oculis is a homeobox gene required for Drosophila visual system development. Genetics. 1994;138:1137–1150. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.4.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos A, Tam B, Ronshaugen M, Frasch M, Levine M, B TAM. pyramus and thisbe: FGF genes that pattern the mesoderm of Drosophila embryos. Genes & Development. 2004;18:687–699. doi: 10.1101/gad.1166404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt N, Molitor A, Somogyi K, Mata J, Curado S, Eulenberg K, Meise M, Siegmund T, Häder T, Hilfiker A, Brönner G, Ephrussi A, Rørth P, Cohen SM, Fellert S, Chung HR, Piepenburg O, Schäfer U, Jäckle H, Vorbrüggen G. Gain-of-function screen for genes that affect Drosophila muscle pattern formation. PLOS Genetics. 2005;1:e14979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tixier V, Bataillé L, Jagla K. Diversification of muscle types: recent insights from Drosophila. Experimental Cell Research. 2010;316:3019–3027. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolkin T, Christiaen L. Development and evolution of the ascidian cardiogenic mesoderm. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2012;100:107–142. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387786-4.00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q, Rong Y, Paterson BM. Stereotypic founder cell patterning and embryonic muscle formation in Drosophila require nautilus (MyoD) gene function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:5461–5466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608739104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernet MF, Meier KM, Baumann-Klausener F, Dorfman R, Weihe U, Labhart T, Desplan C. Genetic dissection of photoreceptor subtype specification by the Drosophila melanogaster zinc finger proteins elbow and no ocelli. PLOS Genetics. 2014;10:e14979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Kauffmann RC, Zhang J, Kladny S, Carthew RW. Overlapping activators and repressors delimit transcriptional response to receptor tyrosine kinase signals in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 2000;103:87–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Okabe M, Hiromi Y. EDL/MAE regulates EGF-mediated induction by antagonizing Ets transcription factor Pointed. Development. 2003;130:4085–4096. doi: 10.1242/dev.00624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]