Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate changes in dietary intake and appetite across the menopausal transition.

Methods

This was a 5-year observational, longitudinal study on the menopausal transition. The study included 94 premenopausal women at baseline (age: 49.9 ± 1.9 yrs; BMI: 23.3 ± 2.3 kg/m2). Body composition (DXA), appetite (visual analogue scale), eating frequency, energy intake (EI) and macronutrient composition (7-day food diary and buffet-type meal) were measured annually.

Results

Repeated-measures analyses revealed that total EI and carbohydrate intake from food diary decreased significantly over time in women who became postmenopausal by year 5 (P > 0.05) compared to women in the menopausal transition. In women who became postmenopausal by year 5, fat and protein intakes decreased across the menopausal transition (0.05 > P < 0.01). Although a decrease in % fat intake was observed during the menopausal transition (P < 0.05), this variable was significantly increased in the postmenopausal years (P < 0.05). Spontaneous EI and protein intake also declined over time and were higher in the years preceding menopause onset (P < 0.05). Desire to eat, hunger and prospective food consumption increased during the menopausal transition and remained at this higher level in the postmenopausal years (0.05 > P< 0.001). Fasting fullness decreased across the menopausal transition (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

These results suggest that menopausal transition is accompanied with a decrease in food intake and an increase in appetite.

Keywords: Energy balance, energy intake, eating frequency, appetite, menopausal transition, body composition

INTRODUCTION

The regulation of food intake and appetite in humans is under the influence of biological, psychological and social factors 1. Although it has been observed that estrogen deficiency increases food intake and appetite in animals 2, there is little evidence to support this in postmenopausal women. Hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle are known to affect energy intake (EI) 1, 3, but food intake during the menopausal transition has been much less studied. The few studies that have investigated this latter issue reported a slight decrease in the calories 4–5, protein and dietary fibers during the menopausal transition 4.

To our knowledge, three longitudinal studies investigated EI during the menopausal transition 4–6. Two used food frequency questionnaire or 24-h recall to measure EI and did not present macronutrient composition 5–6. One of these studies published used direct measures of body composition and measured EI with 4-day food record 4. Interestingly, eating frequency (EF), appetite and objectively measured EI have never been investigated during the menopausal transition.

The objective of this study was to determine changes in dietary intake and appetite during the menopausal transition. We hypothesized that women who will have become postmenopausal at the end of the study will show greater increase in EI and appetite.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited using community advertising and referrals from the Ob/Gyn clinics. Premenopausal women were included if they met the following criteria: (1) premenopausal status (two menstruations in the last 3 months, no increase in cycle irregularity in the 12 months before testing, and a plasma follicular-stimulating hormone level < 30 IU/L as a mean of verification), (2) aged between 47 and 55 years, (3) nonsmoker, (4) BMI between 20 and 29 kg/m2, and (5) reported weight stability (± 2 kg) for 6 months or more before enrollment in the study. Exclusion criteria were (1) pregnancy or having plans to become pregnant, (2) medical problems that could have interfered with outcome variables including cardiovascular and/or metabolic diseases, (3) taking oral contraceptives or hormone therapy, (4) high risk for hysterectomy, and (5) history of drug and/or alcohol abuse. Further details of the MONET menopausal transition study design and recruitment are provided elsewhere 7.

In this study, 94 women completed baseline measurements for dietary intake and appetite variables. Since not all women had completed measurements of all dietary intake and appetite variables for each of the 5 years of data collection, the number of participants varies across analyses for dietary intake and appetite variables (n range from 30 to 56). This study received approval from the University of Ottawa and the Montfort Hospital ethics committees, and written consent was obtained from each participant.

Design

This 5-year menopausal transition study was observational with all outcomes measured at baseline and every year during the course of this 5 year follow-up. As long as women were premenopausal, they were always tested on days 1–8 of the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, ie, when estrogens and progesterone are at their lowest concentrations. Women were tested at the same time of day for all measurements every year. Participants were asked to refrain from any vigorous exercise for at least 24 h before the experimental sessions and were asked to abstain from consuming alcohol on the day prior to measurements.

Menopausal status

Menopausal status was determined yearly by self-reported questionnaire about menstrual bleeding and its regularity. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) was measured yearly during the early follicular phase and was used as a mean of verification of the menopausal status. Women were classified as premenopausal if they reported no changes in menstrual cycle frequency; menopausal transition if they reported irregular cycles characterised by variable cycle length > 7 days different from normal and/or ≥ 2 skipped cycles and an interval of ≥ 60 days of amenorrhea; and finally women were classified as postmenopausal based on their final menstrual period (FMP) and confirmed by 12 months of amenorrhoea and FSH > 30 IU/L 8.

Body weight and composition

Body weight and height were measured with a BWB-800AS digital scale and a Tanita HR-100 height rod (Tanita Corporation of America, Inc, Arlington Heights, IL), respectively, while participants were wearing a hospital gown and no shoes. Body composition was measured by using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; GE-LUNAR Prodigy module; GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI.). Coefficient of variation and correlation for percentage of body fat (%BF) measured in 12 healthy subjects tested in our laboratory were 1.8% and r = 0.99, respectively.

Standardized breakfast and appetite ratings

A standardized breakfast was served after a 12h overnight fast [575 kcal (2400 kJ) and FQ = 0.89 (57% carbohydrates, 13% proteins, 30% lipids)]. Visual analogue scale measurements were taken before, immediately after and every 30 min for a period of 3h after the standardized breakfast 9. The answer to the following questions were used to determine their ‘desire to eat’, ‘hunger’, ‘fullness’, and ‘prospective food consumption (PFC)’, respectively: 1) ‘How strong is your desire to eat?’ (very weak – very strong); 2) ‘How hungry do you feel?’ (not hungry at all – as hungry as I have ever felt); 3) ‘How full do you feel?’ (not full at all –very full); and 4) ‘How much food do you think you could eat?’ (nothing at all – a large amount). The measurements before breakfast were considered as the fasting measurement, and post-meal area under the curve (AUC) were calculated with the trapezoid method as previously described 10. Appetite rating responses at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min were considered in the calculation of the AUC.

Dietary Assessment

Food Diary

Energy and macronutrient intakes were assessed with a 7-day food diary. The time and place of eating of food were also recorded. Participants received oral and written instructions on recording their food intake. Recorded data were carefully verified upon return of the food diary to obtain forgotten data or correct misreported data. The diaries were analysed with Food Processor SQL program (version 10.8; ESHA Research, Salem, OR) using the 2007 Canadian Nutrient Data File.

Buffet-type meal

A buffet-type meal was offered at lunch time (3 hours after a standardized breakfast) and subjects were instructed to eat ad libitum 11–13. All foods were weighed before and at the end of the buffet to the nearest gram. Energy, protein, lipid, carbohydrate and dietary fiber intakes were calculated with the Food Processor SQL program (version 10.8; ESHA Research, Salem, OR) using the 2007 Canadian Nutrient Data File.

Establishing the number of eating occasions

Data from the food diaries were also used to calculate the average number of eating occasions per day, ie, EF. Eating occasions were defined as any occasion when food was consumed 14. The definition excluded drinks (alcoholic drinks, soft drinks, juices, water, or coffee and tea) that were consumed in the absence of food. If 2 eating occasions occurred in ≤ 15 min, both events were counted as a single eating occasion. When > 15 min separated 2 eating occasions, those occasions were considered distinct eating occasions. This method of calculating the number of eating occasions was described previously 14–17.

Assessment of underreporting

Previous research in dietary assessment has indicated persistent errors in self-reported EI 18–19. The use of invalid dietary data can bias the understanding of the association between diet and health or body weight 20. When body weight is stable, total energy expenditure (TEE) is equivalent to EI. Thus, the ratio of reported EI to TEE should be equal to 1. In this study, underreporting was assessed by direct comparison of recorded EI and measured energy expenditure (EE). The ratio between EI and TEE was determined for each subject. Total EE was calculated by using the following formula:

| (1) |

where the factor 1.11 corresponds at the thermic effect of food (TEF), and was fixed at 10% of TEE. Physical activity EE (PAEE) was assessed by using 7-day accelerometry (Actical; Mini Mitter Co, Inc, Bend, OR), and resting EE (REE) was measured by indirect calorimetry (Deltatrac II metabolic cart; SensorMedics Corporation, Yorba Linda, CA). Participants with a ratio of reported EI to EE < 0.74 were classified as underreporters and removed from statistical analysis for EI, macronutrient composition and EF measured by 7-day food diary 21–22.

Statistical analysis

SPSS was used for all analyses (version 17.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Two-way repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to determine main effects of time and menopausal status on EI, macronutrient composition, EF and appetite variables. Post hoc test were done with Tukey-Kramer and adjustment was used for multiple comparisons. These analyses thus included data collected annually for 5 years. Only cases with complete data at all measurement points were retained. Unpaired comparison tests were performed to determine differences between year 0 and years before and after menopause onset in women who became postmenopausal by year 5. In these analyses, year 0 is considered the year within FMP (menopause onset) and is used as control point. For dietary intake and AUC appetite variables, data before and after menopause onset were expressed as the percent of the values at year 0, which was fixed at 100%. Regarding fasting appetite variables, data before and after menopause onset were expressed as the change in mm of the values at year 0. Data are presented as means ± SD. All effects were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the participants

At baseline, women were all premenopausal (age: 49.9 ± 1.9 yrs; body weight: 61.1 ± 6.8 kg; BMI: 23.3 ± 2.3 kg/m2; %BF: 31.4 ± 6.6 %; FM: 19.3 ± 5.4 kg; FFM: 41.2 ± 4.4 kg). As reported previously 7, significant increases for fat mass (FM), %BF, trunk FM and visceral fat were noted while no significant changes were seen for body weight and fat-free mass (FFM) after the 5-year follow-up.

Low energy reporters

Low energy reporters were excluded from the analyses. Thirty-five subjects (37.2%) had ratios of EI/TEE below the cutoff of 0.74 and were identified as underreporters. Data from a total of 59 women were thus included in the final analyses for EI, macronutrient composition and EF measured by 7-day food diary.

Dietary intake and appetite changes over time

Women were divided post hoc based on their menopausal status at year 5: 1) women who remained premenopausal (n = 4) and those classified in the menopausal transition at year 5 (n = 30); 2) women classified as postmenopausal for less than 12 months (Post ≤ 12 months, n = 22); and 3) women who classified as postmenopausal for more than 12 months (Post > 12 months, n = 38). Considering the small number of women who remained premenopausal, they were combined with women who were classified to be in the menopausal transition. No significant differences were found throughout the study for body weight and body composition (Menopausal Transition, n = 34) (data not shown). Postmenopausal status at year 5 in the Post ≤ 12 months group was confirmed a posteriori. Women in this group were contacted after the completion of the 5-year data collection to confirm their menopausal status.

Baseline values for EI, macronutrient composition, EF and appetite were not significantly different between menopausal transition, Post ≤ 12 months and Post > 12 months groups (data not shown). Although Table 1 and 2 present dietary intake and appetite data for only years 1 and 5, analyses were performed using data from years 1 through 5.

Table 1.

Dietary intake variables in response to time and menopausal status (Only values at baseline and year 5 are presented)

| Menopausal Transition | Post ≤ 12 months | Post > 12 months | Repeated Measures ANOVA P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Baseline | Year 5 | Baseline | Year 5 | Baseline | Year 5 | Time | Meno | Meno × Time | |

| n | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | |||

| 7-day food diary | |||||||||

| EI (kcal/day) | 2289.9 ± 447.4 | 2143.9 ± 308.9 | 2175.8 ± 381.5 | 2139.4 ± 440.1 | 2098.7 ± 255.7 | 1845.2 ± 319.1* | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 |

| Protein (%) | 15.8 ± 2.7 | 16.0 ± 2.4 | 15.3 ± 3.4 | 16.5 ± 2.5 | 15.9 ± 2.5 | 17.7 ± 3.1 | NS | NS | NS |

| Carbohydrate (%) | 51.5 ± 4.8 | 49.9 ± 4.5 | 49.7 ± 3.9 | 52.9 ± 4.8 | 51.0 ± 5.2 | 49.6 ± 8.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| Fat (%) | 32.2 ± 3.9 | 33.6 ± 5.5 | 33.2 ± 5.6 | 30.0 ± 2.6 | 30.1 ± 10.5 | 32.7 ± 4.1 | NS | NS | NS |

| Protein (g) | 88.1 ± 21.7 | 86.1 ± 20.3 | 82.5 ± 19.6 | 86.5 ± 15.5 | 82.6 ± 9.8 | 81.2 ± 16.8 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 287.2 ± 63.2 | 267.2 ± 45.1 | 269.5 ± 48.0 | 284.9 ± 70.6 | 268.6 ± 50.4 | 230.0 ± 60.5* | NS | NS | <0.05 |

| Fat (g) | 80.3 ± 21.8 | 79.8 ± 15.4 | 81.5 ± 23.8 | 71.5 ± 16.3 | 70.5 ± 26.0 | 66.6 ± 12.3 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 24.4 ± 15.2 | 24.4 ± 7.0 | 23.7 ± 7.6 | 27.5 ± 7.9 | 27.7 ± 9.7 | 26.8 ± 7.9 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

| EF (eating occasions/day) | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 1.0 | <0.01 | NS | NS |

Post ≤ 12 months: postmenopausal status ≤ 12 months; Post > 12 months: postmenopausal status > 12 months; Meno: menopausal status; EI: energy intake; EF: eating frequency. NS: not significant. Values are mean ± SD.

Significant difference over time within menopausal status (P < 0.05 by post hoc Tukey’s test).

Table 2.

Appetite variables in response to time and menopausal status (Only values at baseline and year 5 are presented)

| Menopausal Transition | Post ≤ 12 months | Post > 12 months | Repeated Measures ANOVA P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Baseline | Year 5 | Baseline | Year 5 | Baseline | Year 5 | Time | Meno | Meno × Time | |

| n | 18 | 18 | 13 | 13 | 25 | 25 | |||

| Fasting desire to eat (mm) | 71.7 ± 45.0 | 97.4 ± 44.9 | 86.8 ± 32.4 | 102.7 ± 32.6 | 79.9 ± 41.5 | 103.8 ± 38.7 | <0.001 | NS | NS |

| n | 17 | 17 | 10 | 10 | 24 | 24 | |||

| Fasting hunger (mm) | 66.0 ± 38.1 | 93.2 ± 41.1 | 70.5 ± 34.8 | 102.9 ± 28.3 | 77.7 ± 34.6 | 101.2 ± 35.6 | <0.001 | NS | NS |

| Fasting fullness (mm) | 31.9 ± 35.0 | 25.4 ± 26.8 | 28.6 ± 28.0 | 18.2 ± 16.1 | 36.3 ± 30.7 | 25.0 ± 32.1 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

| n | 17 | 17 | 10 | 10 | 23 | 23 | |||

| Fasting PFC (mm) | 77.3 ± 30.7 | 83.7 ± 27.1 | 79.8 ± 26.9 | 101.2 ± 29.5 | 76.2 ± 32.4 | 93.3 ± 26.2 | 0.054 | NS | NS |

| n | 18 | 18 | 13 | 13 | 24 | 24 | |||

| AUC desire to eat (mm × min) | 5475.4 ± 3482.8 | 6634.6 ± 4682.0 | 5483.7 ± 2856.8 | 7351.7 ± 4822.4 | 4533.1 ± 3827.3 | 6312.2 ± 4073.2 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

| AUC hunger (mm × min) | 5736.7 ± 3986.2 | 6771.3 ± 4888.4 | 5619.8 ± 3083.7 | 7119.8 ± 4223.3 | 4195.0 ± 3610.8 | 6183.4 ± 3747.8 | <0.05 | NS | NS |

| AUC fullness (mm × min) | 16905.0 ± 6312.1 | 17057.5 ± 5445.3 | 18252.7 ± 5363.3 | 16800.6 ± 4770.5 | 18509.7 ± 5625.5 | 18632.5 ± 4628.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| AUC PFC (mm × min) | 6723.3 ± 4409.4 | 6701.7 ± 4954.0 | 7401.4 ± 4129.6 | 8975.8 ± 4846.5 | 5967.2 ± 4748.1 | 6947.5 ±4346.1 | NS | NS | NS |

Post ≤ 12 months: postmenopausal status ≤ 12 months; Post > 12 months: postmenopausal status > 12 months; Meno: menopausal status; PFC: prospective food consumption; AUC: area under the curve. NS: not significant. Values are mean ± SD.

Energy intake, macronutrient composition and eating frequency

Significant main effects of time were observed for protein, fat and dietary fiber intakes (grams), showing an overall decrease in time (Table 1). A significant main effect of time was also observed for EF, showing an increase over time. Significant menopausal status × time interactions were observed for EI and carbohydrate intake (grams). The Tukey-Kramer post hoc test revealed a significant decrease for EI and carbohydrate intake (grams) in the Post > 12 months group only. There was no main effect of menopausal status on any of the EI, macronutrient composition and EF variables.

Regarding ad libitum EI and macronutrient composition measured with a buffet-type meal only a significant menopausal status × time interaction for % protein intake was observed, revealing a significant increase in the Post > 12 months group only (20.0 ± 5.6 (year 1) vs. 22.5 ± 6.0 (year 5), P < 0.05). Furthermore, there was a main effect of menopausal status on % protein intake, showing a difference between the menopausal transition and the Post > 12 months groups (P < 0.05, data not shown).

Appetite

Significant main effects of time were observed for fasting and AUC desire to eat and hunger, showing an overall increase in time for these variables (Table 2). A significant decrease of fasting fullness was also observed over the 5-year follow-up. A main effect of time almost reaches significance for fasting prospective food consumption (PFC) (P = 0.054). There was no main effect of menopausal status and menopausal status × time interaction on any of the appetite variables.

Effect of the menopausal transition on dietary intake and appetite changes

To further analyze the effect of menopausal transition on dietary intake and appetite, unpaired comparison tests were performed to investigate the differences between years relative to FMP in women who became postmenopausal by the end of the study. For dietary intake and AUC variables, the data are expressed as the percent of the values at year 0, which was fixed at 100%. Regarding fasting appetite variables, the data are expressed as the change in mm of the values at year 0. Year 0 was the year within the FMP (or menopause onset), year +1 was considered as one year after FMP and year −1 was considered as one year before FMP, and so on. Total EI and protein intakes (grams) from 7-day food diary were significantly higher in year −2 and decreased until the onset of menopause (year 0) (Table 3). These variables were also significantly higher at year +1. Percent protein intake was significantly lower at year −4 and significantly higher at year +2. Although % fat intake obtained from 7-day food diary decreased across the menopausal transition years, this variable increased in the postmenopausal years and was significantly higher at year +1. Fat intake (grams) was significantly higher in years −4 through +1 relative to year 0. Percent carbohydrate intake was significantly lower at year −3 and +1. Carbohydrate intake (grams) was significantly higher 2 years prior to menopause onset, whereas dietary fiber intake was significantly higher in the postmenopausal years (+1 and +2). Eating frequency tended to increase across the menopausal transition years and was significantly higher in the postmenopausal years (+1 and +2)relative to year 0.

Table 3.

Changes in dietary intake before and since menopause onset (year 0)

| Values at menopause

|

Years before and since menopause onset

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | s.e.m. | −4 | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | |

| n | 31 | 14 | 20 | 30 | 26 | 31 | 11 | 9 | |

| 7-day food diary | |||||||||

| EI (kcal/day) | 1943.7 | 65.7 | 105.0 ± 16.2 | 101.9 ± 20.0 | 111.0 ± 19.6** | 102.5 ± 19.3 | 100% | 110.9 ± 16.8** | 100.2 ± 16.6 |

| Protein (%) | 16.1 | 0.4 | 91.2 ± 12.4*** | 100.0 ± 13.1 | 101.1 ± 15.9 | 99.5 ± 16.4 | 100% | 103.7 ± 21.6 | 105.9 ± 12.5* |

| Carbohydrate (%) | 52.7 | 1.1 | 97.0 ± 11.7 | 95.6 ± 8.0** | 98.9 ± 11.9 | 97.7 ±10.5 | 100% | 94.2 ± 11.8** | 97.1 ± 9.8 |

| Fat (%) | 30.6 | 0.6 | 108.8 ± 19.4* | 107.8 ± 13.1** | 97.6 ± 24.2 | 104.2 ± 12.2 | 100% | 105.2 ± 20.8* | 100.3 ± 15.4 |

| Protein (g) | 76.7 | 3.1 | 97.9 ± 19.5 | 102.2 ± 23.1 | 112.7 ± 25.3** | 103.7 ± 26.3 | 100% | 113.5 ± 23.2** | 104.5 ± 20.4 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 256.5 | 11.8 | 104.6 ± 27.4 | 99.7 ± 24.0 | 110.5 ± 26.9* | 101.4 ± 24.3 | 100% | 105.3 ± 21.2 | 98.7 ± 20.7 |

| Fat (g) | 65.3 | 2.7 | 119.8 ± 35.4** | 114.6 ± 31.6* | 116.0 ± 29.1** | 109.9 ± 26.0* | 100% | 118.3 ± 32.9** | 100.1 ± 20.1 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 24.6 | 1.7 | 91.9 ± 29.0 | 93.3 ± 40.8 | 118.9 ± 54.6 | 108.2 ± 45.7 | 100% | 118.5 ± 38.1** | 120.9 ± 36.4** |

| EF (eating occasions/day) | 5.0 | 0.2 | 91.5 ± 17.8* | 94.3 ± 14.7* | 99.8 ± 20.2 | 99.7 ± 21.0 | 100% | 110.6 ± 21.4** | 106.3 ± 15.0* |

| n | 17 | 29 | 45 | 40 | 46 | 27 | 13 | ||

| Buffet-type meal | |||||||||

| EI (kcal) | 505.0 | 31.2 | 117.6 ± 46.6* | 113.8 ± 51.2 | 114.6 ± 43.9* | 107.9 ± 58.3 | 100% | 88.6 ± 27.4** | 89.8 ± 36.0 |

| Protein (%) | 18.6 | 0.9 | 106.3 ± 28.1 | 115.3 ± 47.0* | 106.9 ± 35.9 | 107.0 ± 28.6 | 100% | 112.5 ± 25.2** | 132.9 ± 46.8*** |

| Carbohydrate (%) | 49.7 | 1.5 | 103.8 ± 30.5 | 97.7 ± 23.8 | 100.5 ± 27.0 | 103.6 ± 33.9 | 100% | 104.1 ± 25.9 | 108.1 ± 40.3 |

| Fat (%) | 33.4 | 1.6 | 98.1 ± 33.6 | 118.1 ± 61.2* | 110.1 ± 48.3 | 104.0 ± 45.6 | 100% | 98.8 ± 46.5 | 104.1 ± 37.9 |

| Protein (g) | 22.3 | 1.5 | 124.1 ± 64.6* | 118.9 ± 40.0** | 117.1 ± 43.6** | 106.3 ± 40.8 | 100% | 97.9 ± 33.9 | 110.7 ± 34.5* |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 62.8 | 4.3 | 116.3 ± 48.6* | 109.3 ± 51.6 | 115.8 ± 55.3 | 104.6 ± 49.4 | 100% | 93.1 ± 39.4 | 96.8 ± 48.0 |

| Fat (g) | 19.2 | 1.5 | 121.5 ± 72.1* | 146.1 ± 128.7* | 129.9 ± 86.1* | 128.2 ± 118.8 | 100% | 88.2 ± 53.2 | 99.4 ± 69.3 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 5.6 | 0.4 | 92.0 ± 48.0 | 110.6 ± 93.7 | 123.8 ± 85.4 | 122.6 ± 100.0 | 100% | 108.5 ± 45.1 | 105.6 ± 65.9 |

EI: energy intake; EF: eating frequency. Values are mean ± SD for each year expressed as the percent of the values at year 0 (menopause onset), which was standardized to 100%. Significantly different compared to year 0 (* P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001).

Energy intake from buffet-type meal tended to decrease across the menopausal transition years and was significantly lower at year +1 compared with menopause onset (Table 3). Relative spontaneous protein intake was significantly higher in the postmenopausal years. Protein and fat intakes (grams) were significantly higher through the menopausal transition years. Percent fat intake and carbohydrate intake (grams) were significantly higher at years −3 and −4, respectively.

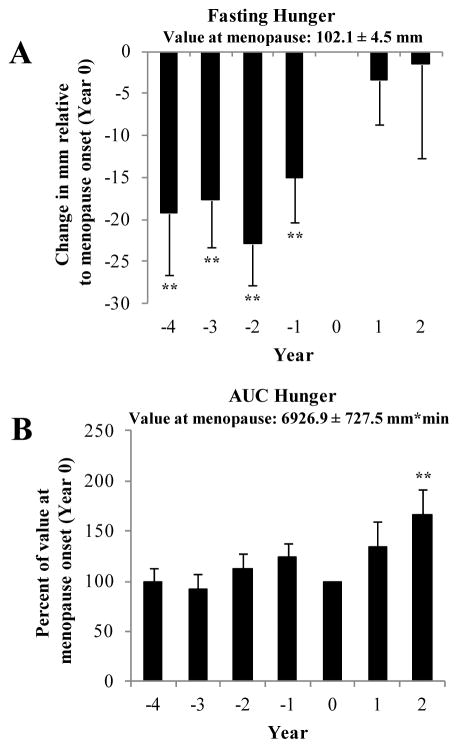

Fasting desire to eat, fasting hunger (see Figure 1 Panel A) and fasting PFC were significantly lower during the menopausal transition years and increased until the onset of menopause (P < 0.05). These variables remained at this higher level in the postmenopausal years (year +1 and +2). Fasting fullness was significantly higher at year −3 and decreased until the onset of menopause (year 0) (P < 0.05). AUC desire to eat, hunger (see Figure 1 Panel B) and PFC tended to increase across the menopausal transition years and was significantly higher at year +2 compared with menopause onset( P< 0.05). Data not shown.

Figure 1.

Prospective changes in fasting (A) and area under the curve (AUC) (B) for hunger relative to menopause onset (year 0). Values are mean ± SEM. The number of participants at each year are as follows: Panel A- Year −4 (n=17), −3 (n=27), −2 (n=46), −1 (n=40), 0 (n=47), 1 (n=27) and 2 (n=13). Panel B- Year −4 (n=17), −3 (n=30), −2 (n=45), −1 (n=41), 0 (n=47), 1 (n=27) and 2 (n=13). Values are expressed as the change in mm of the values at year 0 (menopause onset) for fasting hunger. AUC hunger is expressed as the percent of the value at year 0 (menopause onset). Significantly different compared to year 0 (**P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

We found that total EI and carbohydrate intake decreased significantly over time in women who became postmenopausal by year 5. Furthermore, fat and protein intakes also decreased across the menopausal transition. Although a decrease in % fat intake was observed during the menopausal transition, this variable was significantly increased in the years after menopause onset. Buffet EI and protein intake also declined over time and were higher in the years preceding menopause onset. Lastly, appetite increased during the menopausal transition and remained higher in the postmenopausal years.

In the present study, a decrease in EI in postmenopausal women was observed, which is the opposite of what has been reported in ovariectomized rats 1–3. However, the present results on EI are consistent with results reported in other studies that showed a decrease in EI across the menopausal transition 4–5. Although we showed a decrease in EI in postmenopausal women (approximately 254 kcal/day), the mean body weight changed minimally over time 7. This could be likely explained by a reduction in EE (approximately 200 kcal/day), mainly characterized by a decrease in physical activity EE and a shift to a more sedentary lifestyle, that we have reported previously 23. In the present study, we found that changes in EI were significantly correlated with changes in PAEE (r= 0.26, P < 0.05). Moreover, women who may be more concerned about their weight at the time of menopause, may voluntarily change dietary patterns to avoid weight gain 24. Similar to results from Lovejoy et al. 4, we noted a reduction in protein intake over time during the menopausal transition, which could possibly impact satiety 25. Previously published data suggest that estrogen deficiency in animals resulted in an increase in food intake with a macronutrient-specific increase in fat intake 26. In the present study, although % fat intake decreased across the menopausal transition years, this variable increased during the postmenopausal years. A diet low in fat could be beneficial in women approaching menopause. Indeed, a randomized clinical trial conducted over a 5-y period aimed at preventing weight gain during menopause showed that a diet low in fat (25%) was associated with better weight maintenance during the menopausal transition 27. Similar to results from the food diaries, a decrease in EI, protein and fat intakes were also noted during the ad libitum buffet.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of appetite-related variables during the menopausal transition. Our results show that desire to eat, hunger and PFC increased during the menopausal transition and remained higher in the postmenopausal years. Moreover, we observed that fasting fullness decreased during the menopausal transition. Results remained significant after adjustments for changes in EI. These results may be partly explained by the observation that ghrelin level was shown to be higher during the menopausal transition compared to both pre- and postmenopausal women 28. The observed changes in appetite in the present study could indicate a risk for positive energy balance and weight gain over time. However, we did not observe an increase in EI during the menopausal transition. Eating behaviors, such as dietary restraint, could explain the fact that we have observed a decrease in EI and an increase in appetite. Nevertheless, in the present study, no significant changes in dietary restraint [measured by the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire 29] were noted (data not shown).

This study presents some limitations. First, the small sample size and the healthy homogenous population (healthy women with a BMI less than 30 kg/m2) limits the generalizability of our results. However, it is important to mention that 45% of the women aged between 40 to 59 years in the Canadian population present a BMI between 20 and 29 kg/m2. Second, although our population was non-obese women based on BMI, 59% had a %BF > 30% and 32% had a %BF ≥ 35%, which are considered as overweight and obese, respectively, based on the American College of Sports Medicine 30. Third, appetite can differ across the day. In our study, the measurement of appetite was done only in the morning over a 3-hour period up until lunch time. However, it was shown that appetite sensations measured in response to a standardized breakfast test meal, as we used in our study, represented markers of overall intake 31–32. Fourth, although 67% of the women became postmenopausal by year 5, the relatively short duration of the follow-up, particularly during the postmenopausal period (2 years only), represents another limitation. Finally, women who remained premenopausal (n=4) were combined to those who were in the menopausal transition resulting in the absence of a premenopausal control group. Nonetheless, the prospective design in a very well-characterized cohort of women allows for consideration of within-subject change and is more informative than cross-sectional design. Moreover, the present study took measures to ensure that underreporting did not bias the results. We screened the individual food diary results for underreporting by using validated procedures 21–22 and we excluded all low energy reporters from the analyses. Finally, gold standard measure (DXA) for body composition and objective measures of EI and appetite were used.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this study suggests that menopausal transition is accompanied with a decrease in EI and an increase in appetite. Although middle-aged women tend to experience changes in body composition, these changes do not seem to be the result of an increase in EI.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for their devoted participation and to the staff of Behavioural and Metabolic Research Unit (BMRU) for their contribution to this study. We especially want to thank Ann Beninato for her significant role in the collection of the data and overall study coordination. This study was supported by CIHR (Canadian Institute for Health Research) grants: 63279 MONET study (Montreal Ottawa New Emerging Team). K Duval is a recipient of the FRSQ (Fonds de la recherche en Santé du Québec) Doctoral support program. R Rabasa-Lhoret is a recipient of the FRSQ clinical researcher scholarship and holds the J-A DeSève chair.

Supported by: Canadian Institutes of Health Research

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None Disclosed

References

- 1.Hirschberg AL. Sex hormones, appetite and eating behaviour in women. Maturitas. 2012;71(3):248–56. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wade GN. Some effects of ovarian hormones on food intake and body weight in female rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;88(1):183–93. doi: 10.1037/h0076186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butera PC. Estradiol and the control of food intake. Physiol Behav. 2010;99(2):175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovejoy JC, Champagne CM, de Jonge L, Xie H, Smith SR. Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(6):949–58. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macdonald HM, New SA, Campbell MK, Reid DM. Longitudinal changes in weight in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women: effects of dietary energy intake, energy expenditure, dietary calcium intake and hormone replacement therapy. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(6):669–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wing RR, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Meilahn EN, Plantinga PL. Weight gain at the time of menopause. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(1):97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdulnour J, Doucet E, Brochu M, Lavoie JM, Strychar I, Rabasa-Lhoret R, et al. The effect of the menopausal transition on body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors: a Montreal-Ottawa New Emerging Team group study. Menopause. 2012;19(7):760–7. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318240f6f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, et al. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) Park City, Utah, July, 2001. Menopause. 2001;8(6):402–7. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill AJ, Blundell JE. Macronutrients and satiety: the effects of a high-protein or high-carbohydrate meal on subjective motivation to eat and food preferences. Nutr Behav. 1986;3:133–144. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doucet E, St-Pierre S, Almeras N, Tremblay A. Relation between appetite ratings before and after a standard meal and estimates of daily energy intake in obese and reduced obese individuals. Appetite. 2003;40(2):137–43. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(02)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pomerleau M, Imbeault P, Parker T, Doucet E. Effects of exercise intensity on food intake and appetite in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(5):1230–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doucet E, Laviolette M, Imbeault P, Strychar I, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Prud’homme D. Total peptide YY is a correlate of postprandial energy expenditure but not of appetite or energy intake in healthy women. Metabolism. 2008;57(10):1458–64. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arvaniti K, Richard D, Tremblay A. Reproducibility of energy and macronutrient intake and related substrate oxidation rates in a buffet-type meal. Br J Nutr. 2000;83(5):489–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drummond SE, Crombie NE, Cursiter MC, Kirk TR. Evidence that eating frequency is inversely related to body weight status in male, but not female, non-obese adults reporting valid dietary intakes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22(2):105–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yannakoulia M, Melistas L, Solomou E, Yiannakouris N. Association of eating frequency with body fatness in pre- and postmenopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(1):100–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berteus Forslund H, Torgerson JS, Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK. Snacking frequency in relation to energy intake and food choices in obese men and women compared to a reference population. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29(6):711–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duval K, Strychar I, Cyr MJ, Prud’homme D, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Doucet E. Physical activity is a confounding factor of the relation between eating frequency and body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(5):1200–5. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey RL, Mitchell DC, Miller C, Smiciklas-Wright H. Assessing the effect of underreporting energy intake on dietary patterns and weight status. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livingstone MB. Assessment of food intakes: are we measuring what people eat? Br J Biomed Sci. 1995;52(1):58–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lissner L, Heitmann BL, Lindroos AK. Measuring intake in free-living human subjects: a question of bias. Proc Nutr Soc. 1998;57(2):333–9. doi: 10.1079/pns19980048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen LF, Tomten H, Haggarty P, Lovo A, Hustvedt BE. Validation of energy intake estimated from a food frequency questionnaire: a doubly labelled water study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(2):279–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black AE, Cole TJ. Within- and between-subject variation in energy expenditure measured by the doubly-labelled water technique: implications for validating reported dietary energy intake. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(5):386–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duval K, Prud’homme D, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Strychar I, Brochu M, Lavoie JM, et al. Effects of the menopausal transition on energy expenditure: a MONET Group Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(4):407–11. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green KL, Cameron R, Polivy J, Cooper K, Liu L, Leiter L, et al. Weight dissatisfaction and weight loss attempts among Canadian adults. Canadian Heart Health Surveys Research Group. Cmaj. 1997;157(Suppl 1):S17–S25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paddon-Jones D, Westman E, Mattes RD, Wolfe RR, Astrup A, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Protein, weight management, and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1558S–1561S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1558S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geiselman PJ, Martin JR, Vanderweele DA, Novin D. Dietary self-selection in cycling and neonatally ovariectomized rats. Appetite. 1981;2(2):87–101. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(81)80002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, Boraz MA, Kuller LH. Lifestyle intervention can prevent weight gain during menopause: results from a 5-year randomized clinical trial. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(3):212–20. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sowers MR, Wildman RP, Mancuso P, Eyvazzadeh AD, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Rillamas-Sun E, et al. Change in adipocytokines and ghrelin with menopause. Maturitas. 2008;59(2):149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ACSM. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 4. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drapeau V, King N, Hetherington M, Doucet E, Blundell J, Tremblay A. Appetite sensations and satiety quotient: predictors of energy intake and weight loss. Appetite. 2007;48(2):159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drapeau V, Blundell J, Therrien F, Lawton C, Richard D, Tremblay A. Appetite sensations as a marker of overall intake. Br J Nutr. 2005;93(2):273–80. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]