Abstract

The paper is an update of 2011 Standards for Ultrasound Assessment of Salivary Glands, which were developed by the Polish Ultrasound Society. We have described current ultrasound technical requirements, assessment and measurement techniques as well as guidelines for ultrasound description. We have also discussed an ultrasound image of normal salivary glands as well as the most important pathologies, such as inflammation, sialosis, collagenosis, injuries and proliferative processes, with particular emphasis on lesions indicating high risk of malignancy. In acute bacterial inflammation, the salivary glands appear as hypoechoic, enlarged or normal-sized, with increased parenchymal flow. The echogenicity is significantly increased in viral infections. Degenerative lesions may be seen in chronic inflammations. Hyperechoic deposits with acoustic shadowing can be visualized in lithiasis. Parenchymal fibrosis is a dominant feature of sialosis. Sjögren syndrome produces different pictures of salivary gland parenchymal lesions at different stages of the disease. Pleomorphic adenomas are usually hypoechoic, well-defined and polycyclic in most cases. Warthin tumor usually presents as a hypoechoic, oval-shaped lesion with anechoic cystic spaces. Malignancies are characterized by blurred outlines, irregular shape, usually heterogeneous echogenicity and pathological neovascularization. The accompanying metastatic lesions are another indicator of malignancy, however, final diagnosis should be based on biopsy findings.

Keywords: salivary glands, ultrasound, standards, parotid gland, submandibular gland

Abstract

W publikacji przedstawiono aktualizację standardów Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego dotyczących badania ultrasonograficznego gruczołów ślinowych, wydanych w 2011 roku. Opisano w niej obecne wymogi techniczne dotyczące aparatów ultrasonograficznych, technikę przeprowadzania badania i pomiarów oraz zasady wykonywania opisu badania. Omówiono zarówno prawidłowy obraz ultrasonograficzny ślinianek, jak i najważniejsze patologie w obrębie tych gruczołów, takie jak: stany zapalne, sialozy, kolagenozy, urazy oraz procesy rozrostowe, ze szczególnym podkreśleniem cech zmian o wysokim ryzyku złośliwości. W przypadku ostrych, bakteryjnych zapaleń ślinianki są hipoechogeniczne, powiększone bądź normalnego rozmiaru, ze zwiększonym przepływem miąższowym. W zapaleniach wirusowych echogeniczność jest wyraźnie podwyższona. W zapaleniach przewlekłych widoczne są zmiany degeneracyjne. W kamicy uwidocznić można hiperechogeniczne złogi z towarzyszącym cieniem akustycznym. W sialozach dominują cechy zwłóknienia miąższu. Zespół Sjögrena daje różne obrazy zmian w miąższu ślinianek na różnych etapach choroby. Gruczolaki wielopostaciowe to zwykle zmiany hipoechogeniczne, dobrze odgraniczone i najczęściej policykliczne. Guz Warthina jest zazwyczaj zmianą hipoechogeniczną, owalną, z torbielowatymi przestrzeniami bezechowymi. Zmiany złośliwe cechują się zatartymi granicami, nieregularnym kształtem, zwykle niejednorodną echogenicznością i patologicznym unaczynieniem. Towarzyszące zmianie przerzutowe węzły chłonne są dodatkowym aspektem świadczącym o złośliwym jej charakterze, jednak ostateczne rozpoznanie można postawić na podstawie wyniku biopsji.

Introduction

Ultrasound is currently the most useful technique for salivary gland imaging. The glands are routinely evaluated for their size, shape as well as echogenicity and potential focal lesions. Doppler techniques can provide valuable information in some cases, allowing for the assessment of parenchymal blood flow, glandular tissue vascular system and the vasculature of focal lesions(1, 2). Equipment that allows for the visualization of even very small structural changes in the gland as well as knowledge on the wide range of salivary gland pathologies are crucial for the highest possible diagnostic value of ultrasound. Therefore, we present the various aspects of a properly performed ultrasound examination of the salivary glands to reduce the number of difficulties encountered during interpretation.

Equipment

Salivary gland ultrasound requires high-parameter equipment. This requirement is only met by electronic linear transducer approx. 4 cm in length, with a frequency of at least 7 MHz. Broadband transducers with a variable frequency between 7 and 15 MHz are recommended as optimal. The transducers should feature at least 128 transmitter and receiver channels as well as the Doppler option (color and power Doppler). The ultrasound apparatus should be equipped with a high-resolution monitor with at least 256-grade greyscale, image enlargement option as well as distance, area and volume measurement applications(3, 4).

Documentation

The device should additionally feature a color or monochrome videoprinter to ensure proper photographic documentation. New ultrasound devices are also equipped with DVD recorder and an USB input, allowing for the recording of images on a portable flash memory(4).

Technique

The parotid glands

The test is performed in a patient with the head slightly tilted to the left or right for a better exposure of the examined area. The glands are examined in cross-sections – perpendicular to the mandibular branch and in the axis parallel to the mandibular branch. The superficial parenchyma below the mandibular angle or the deeper-situated parts of the gland, which penetrate towards the parapharyngeal space, should not be omitted. When attempting to trace the parotid duct (Stenson's duct), it is advisable to insert a finger in the oral cavity and place it on the inside of the cheek on the papilla, which is an outlet of the parotid duct (under normal conditions the visualization of salivary ducts is often unsuccessful) (4–6).

Patients referred for salivary gland imaging require an accurate bilateral assessment of the glands and, in many cases, an examination of the entire neck (e.g. to detect enlarged lymph nodes) (4, 7).

The submandibular and sublingual glands

The patient should be placed in a supine position with the head maximally tilted back to ensure free access to the submandibular area. Placing a finger of the other hand in the sublingual area can sometimes help recognize the spatial orientation of the evaluated structures. Furthermore, the patient should, if possible, remove the saliva from the mouth as multiple air bubbles it contains are a common cause of artifacts. The use of Doppler techniques allows to distinguish between vessels (e.g. the facial artery) and the potential dilated intraglandular ducts. This in turn allows for a visualization of increased parenchymal blood flow in acute salivary inflammation and pathological neovascularization in proliferative diseases. If focal lesions are detected, their size and location should be determined. The structure and echogenicity of the lesion should also be described. If possible, color and power Doppler should be performed. In the case of sialolithiasis, it is necessary to trace the visible part of the excretory duct and document the presence of deposits(3, 4).

The sublingual glands are located bilaterally on the oral diaphragm, between the hyoglossus muscle and the mylohyoid muscle. Although these glands often remain unnoticed during a routine examination of this region, their borders can be usually traced in tumors or retention cysts(4).

An ultrasound image of normal salivary glands

Salivary glands, which are paired organs, are located symmetrically in identical topographical conditions. Since the ultrasonographic image of corresponding glands resembles a reflection in a mirror, their shape and size are comparable under normal conditions(3, 8).

It is difficult to establish clear standards, particularly those regarding the volume and size of the salivary glands. Difficulties determining the standard size of the salivary glands are due to e.g. high inter-subject variability and significant differences in the size of these glands between children and adults. Their actual size measured in different planes seems relatively easy to assess duo to their superficial location and clear borders of normal glandular parenchyma(9).

Determination of the parenchymal volume is very difficult and encumbered with a significant error. This is due to the complex shape of these glands, whose soft parenchyma is modeled by the adjacent, more compact structures. Therefore, the shape of the parotid and submandibular glands depends on both, the shape of the mandible and the degree of muscular development (e.g. the masseter muscles or oral floor muscles)(8, 9). The commonly used methods for volume measurement, which are based on a comparison between the evaluated structure and a regular mass generated based on the basic dimensions, proved unsuccessful in the case of salivary glands(9).

Normal salivary glands have homogeneous echogenicity, comparable to that of other lobular glands, such as the thyroid. Their vessels are clearly visible and are an important anatomical element. The course of the facial artery can be traced in the submandibular salivary parenchyma, while the retromandibular vein is clearly visible during parotid gland examination. Since it is impossible to visualize the facial nerve within the parotid gland, the location of the retromandibular vein is its valuable topographical landmark(3, 6, 10).

The intraglandular salivary ducts cannot be seen under normal conditions. Their marked presence is an early symptom of discharge retention and processes leading to increased wall thickness and echogenicity. This occurs in inflammatory processes (including autoimmune inflammatory processes). The excretory ducts of the parotid and submandibular glands (extraglandular) are also invisible under normal conditions, but may be seen after minor compression in the region of their outlet into the oral cavity with a simultaneous stimulation of increased salivary secretion using a food stimulus (1, 6, 8).

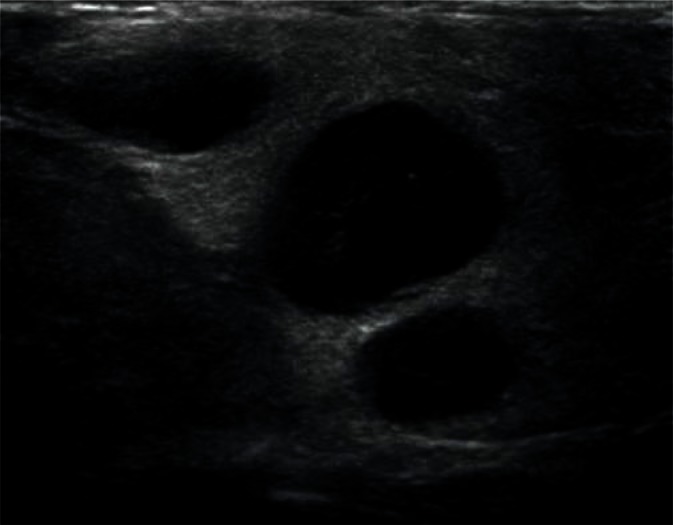

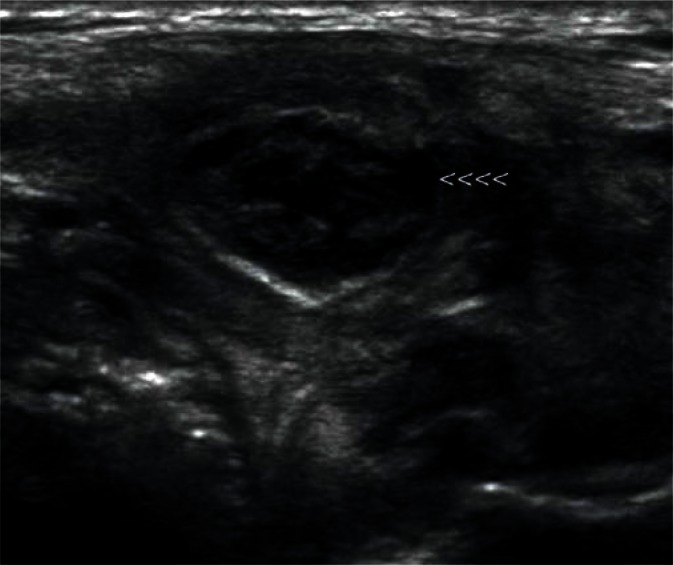

The intraglandular lymphatic tissue clusters known as the intraglandular lymph nodes, are another anatomical element, which occurs under physiological conditions, but is also very important in salivary pathologies. The size and the number of these hypoechoic structures shows a very high inter-subject variability.

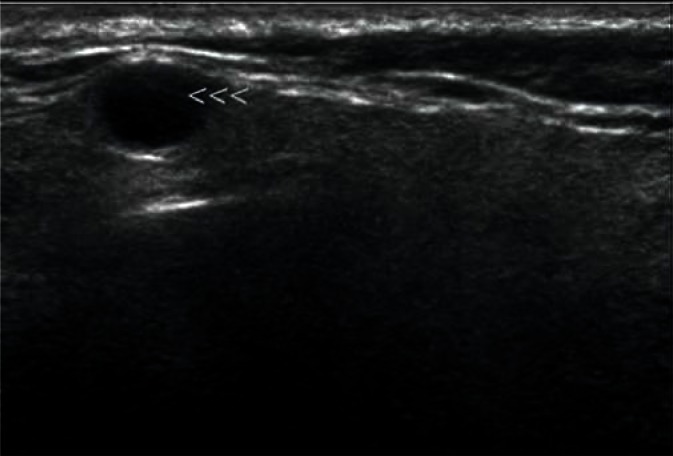

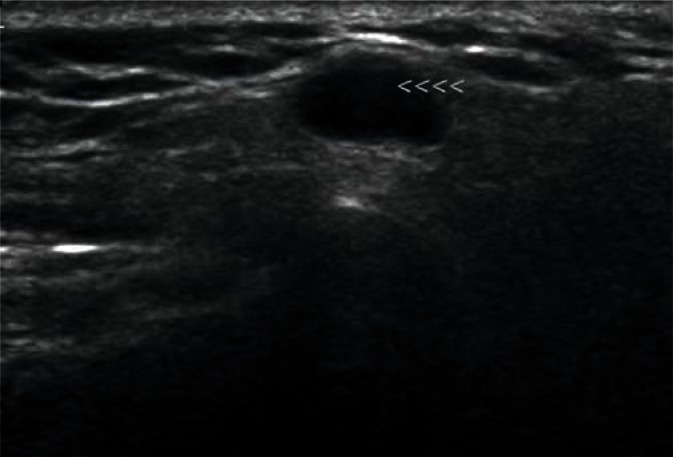

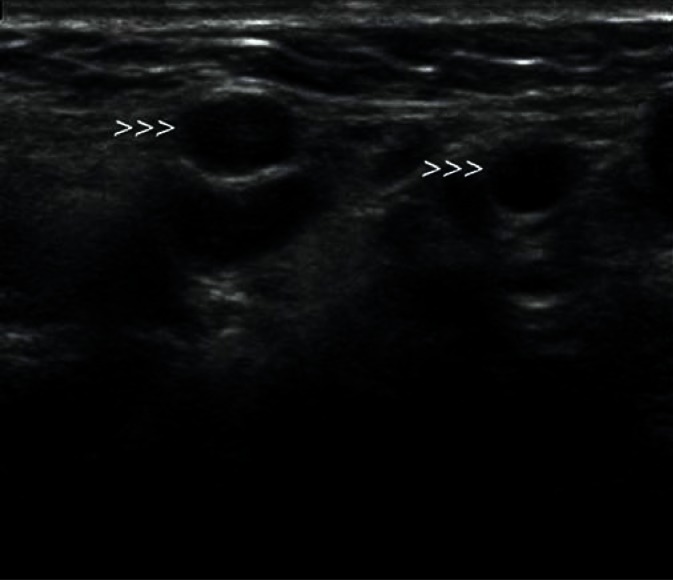

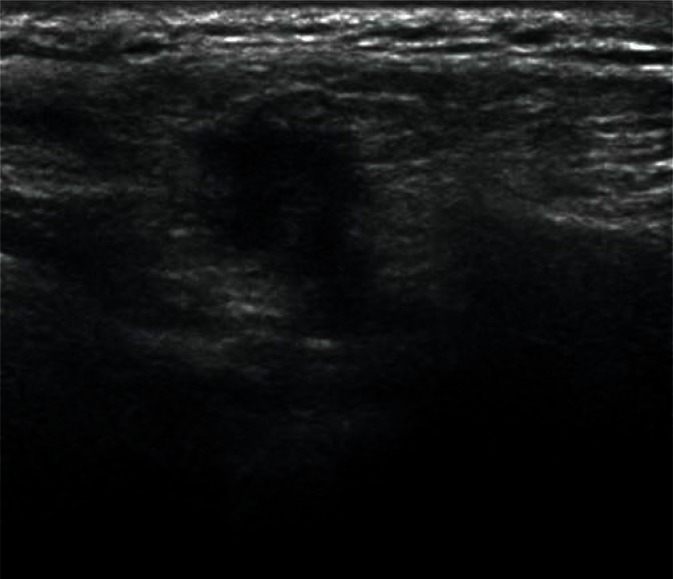

They are most frequently located in the posterior lower pole of the parotid gland and in the region where the submandibular duct exits the parenchyma (Fig. 1, 2). They are generally spindle-shaped. Furthermore, they often contain centrally located light bands, which correspond to the hilus with vasculature typical of lymph nodes(3, 7).

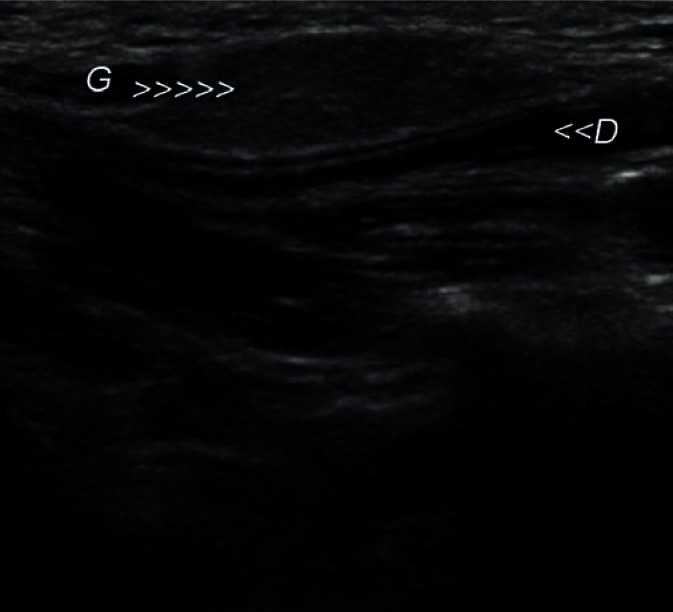

Fig. 1.

Typical, intraglandular lymph node in the parotid gland (indicated by arrowheads)

Fig. 2.

Another intraglandular lymph node in the parotid gland (indicated by arrowheads)

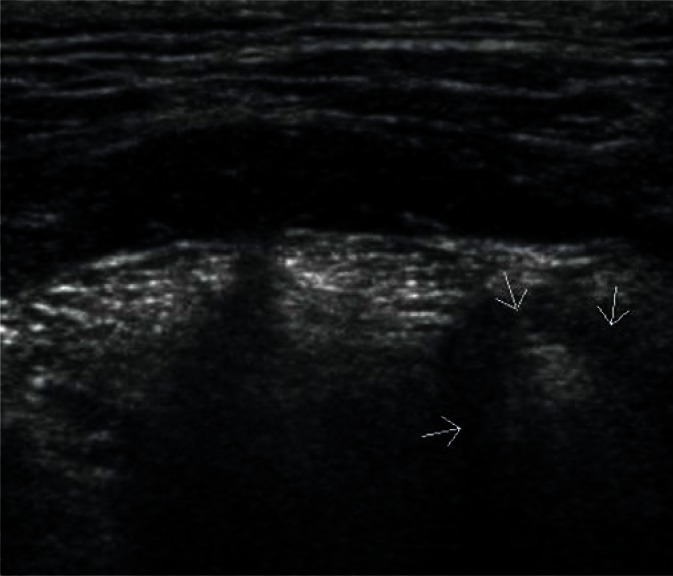

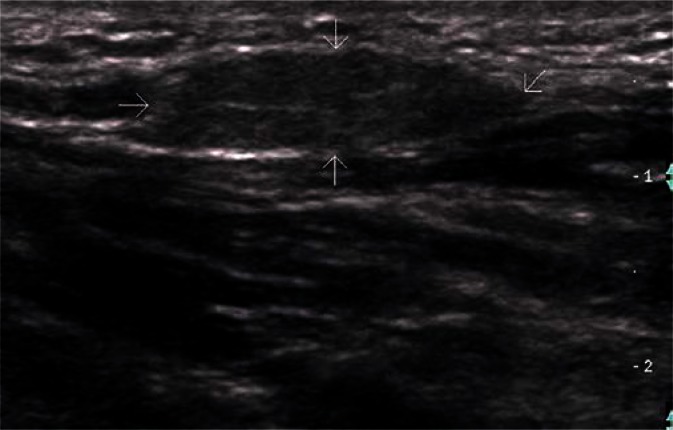

Sublingual glands are a pair of major salivary glands (unlike small glands scattered throughout the oral cavity), which are most difficult to visualize. They are located on both sides of the tongue on the oral diaphragm between the hyoglossus muscle and the mylohyoid muscle (Fig. 3). Normal sublingual glands often remain unnoticed against the adjacent isoechoic tissues during a routine examination of this region. They become easily visualized in the case of focal lesions or altered echogenicity in the course of inflammatory processes(1, 3).

Fig. 3.

Normal parotid gland (indicated by arrows)

Salivary gland diseases in ultrasound images

In most cases, lesions are found in one of the salivary glands. Widespread (viral) infections, salivary gland edema in the course of different systemic diseases and metabolic disorders (known as sialoses) as well as autoimmune diseases are an exception.

Enlargement of one of the salivary glands is easily noticeable due to the different size compared to the corresponding gland as well as a striking change in the shape of the gland. Focal lesions located in the salivary glands are an exception since inflammatory processes and secretory retention also result in rounded and smooth outlines of the gland. This phenomenon allows to identify gland enlargement without the knowledge on its previous size or even despite low values from the measurements performed in typical planes(11, 12).

Salivary gland diseases can be classified into developmental disorders, inflammations, sialoses, tumors and post-traumatic lesions.

An ultrasound image of normal salivary glands is characterized by a homogeneous echogenicity. Pathological salivary glands show altered echogenicity, depending on the type and duration of the disease(12).

Salivary gland developmental disorders

The most common developmental disorders of the salivary glands are hypoplasia of one of the salivary glands and an accessory buccal salivary gland joined with the excretory duct (Figs. 4, 5). The hypoplastic picture is quite obvious and only needs to be distinguished from a postinflammatory gland atrophy. The echogenicity of the accessory buccal salivary gland is identical to that of an adjacent parotid gland. In the case of uncertainty, scintigraphy and fine-needle biopsy are of decisive importance(12–14).

Fig. 4.

Accessory parotid gland in the cheek

Fig. 5.

Accessory parotid gland in the cheek (G) with a visible Stenson duct (D) located in its vicinity

Inflammation of the salivary gland

The changes in the picture of inflammatory salivary glands depend on the nature of the disease. The image of a salivary gland affected by bacterial infection, which spreads via salivary ducts, is completely different from a salivary gland affected by viral infection, which is of an interstitial nature.

In bacterial inflammation, the parenchymal echogenicity of the salivary gland initially decreases, with an increasing volume of the gland due to edema (Fig. 6). If the inflammation is chronic, the echogenicity of the gland gradually becomes heterogeneously increased, with strong parenchymal bands of echoes corresponding to fibrosis. Since inflammatory processes often occur secondary to lithiasis, dilated intraglandular and excretory ducts can be observed. It is also often possible to visualize deposits with varying degrees of calcification in their lumen. Calcifications associated with lithiasis mostly affect the submandibular glands (Figs. 7, 8), whereas they are rarely seen in the parotid glands. Küttner's tumor (Fig. 9), which may be clinically confused with malignancy, is an interesting example of chronic sclerosing inflammation of the submandibular gland. The ultrasonographic image shows a heterogeneous, reduced echogenicity of the affected parenchyma with cirrhosis-like hyperechoic bands of fibrosis(15–17).

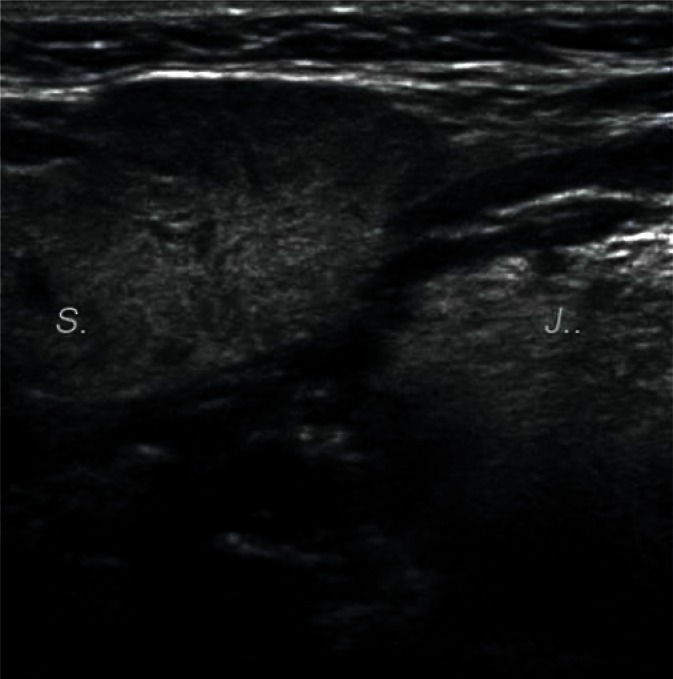

Fig. 6.

Enlarged right submandibular gland with inflammatory lesions (S). Lingula is indicated by ‘J’

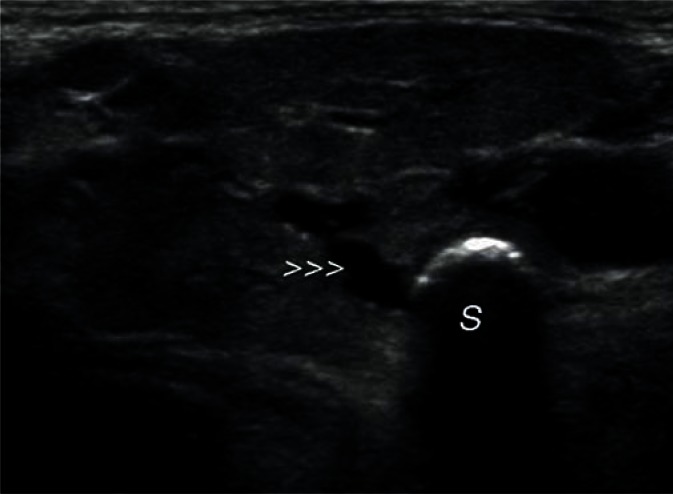

Fig. 7.

A deposit (S) (stone) in the proximal segment of the submandibular duct (arrowheads)

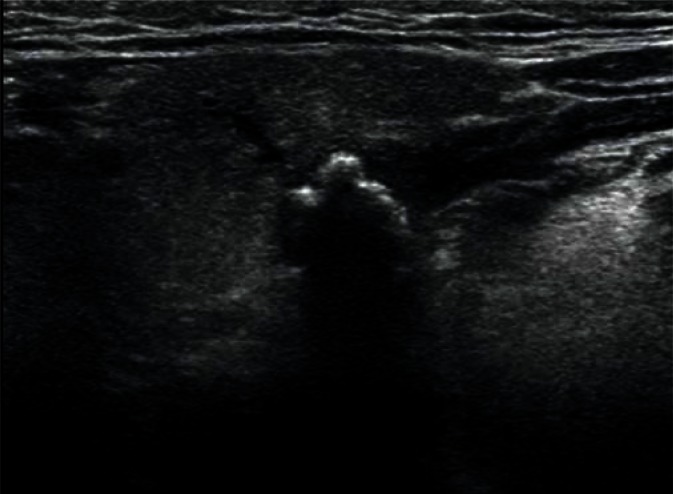

Fig. 8.

Multiple small deposits in the junction of the intraglandular ducts of the right submandibular gland

Fig. 9.

Küttner's tumor in the right submandibular gland (size: 12 × 9 mm)

A common inflammation of the salivary glands (mumps) can affect one or a number of salivary glands and is characterized by gland enlargement (edema) as well as heterogeneous and increased echogenicity. Distinct outlines of dilated vessels with increased blood flow are seen in Doppler imaging in all cases of salivary gland inflammation (especially in the acute phase) (Fig. 10). Unfavorable course of inflammation, especially in immunocompromised patients, may lead to abscess formation in the glandular parenchyma, or even neck phlegmon. In such cases, ultrasound is crucial for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of these lesions(18–21).

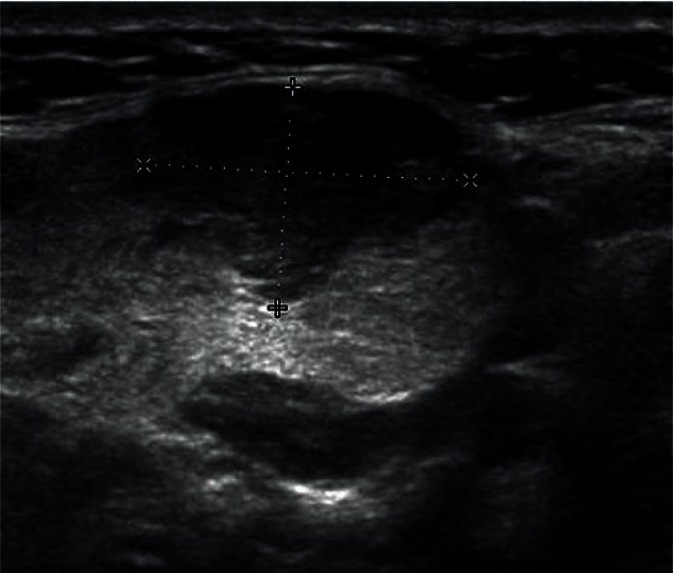

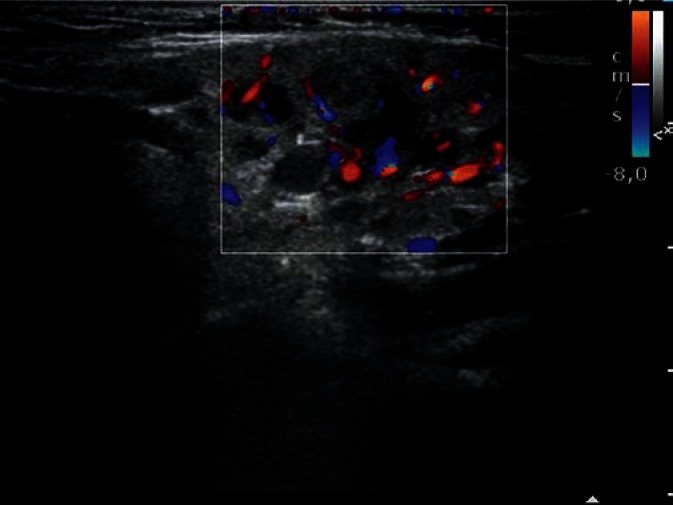

Fig. 10.

Recurrent inflammation of the parotid gland

It should be noted that the inflammatory involvement of salivary glands may result from the processes that occur in their immediate vicinity, e.g. actinomycosis of the neck. Ultrasound images of the inflammatory infiltrate are very characteristic in these cases. The boundaries between the different structures of the affected region usually become completely blurred(22).

Salivary gland diseases caused by immune disorders are a special group of inflammatory conditions. They belong to rhe umatic diseases and are governed by the same rules as connective tissue diseases (collagenoses). In the salivary glands, they can manifest as lesions limited to the parotid glands, parotid and submadibular glands or all major salivary glands. In most cases, however, they are associated with lacrimal gland pathology.

Sjögren syndrome and Mikulicz-Radecki syndrome have been distinguished, depending on the course and severity of disease (Figs. 11, 12). The course of these diseases can vary significantly, with frequent periods of exacerbations and remissions, additionally hindering the diagnosis. Furthermore, the ultrasonographic picture of salivary glands shows significant variability and dynamics. Although it may vary in the same patient in different periods of the disease, the final outcome is basically the same, i.e. adipose tissue atrophy with an increasing volume of proliferative lymphoid tissue. Initially, it resembles multiple small intraglandular lymph nodes. Later, hypoechoic structures (single and grouped) showing ultrasonographic features of reactive lymph nodes occur. In periods of exacerbation, intense blood flow is registered in microvascular systems, which are typical of vessels located in the nodal hilus. The late stages of the disease are characterized by significant parenchymal fibrosis and sparse parenchymal blood flow(23–25).

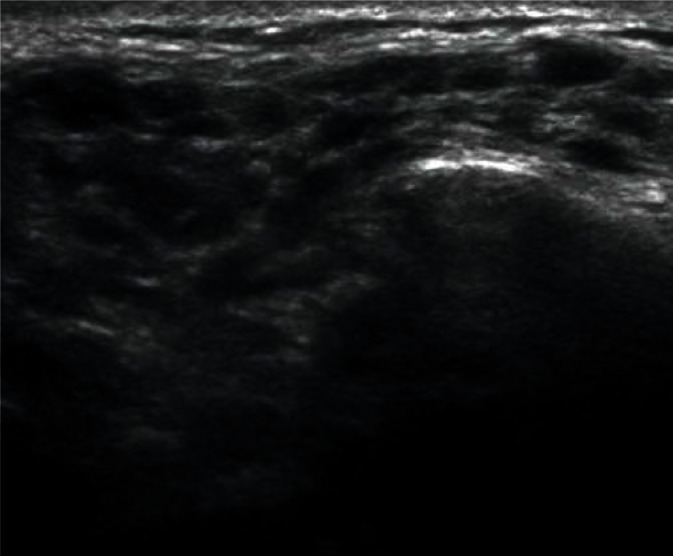

Fig. 11.

Parotid parenchyma in Sjögren syndrome

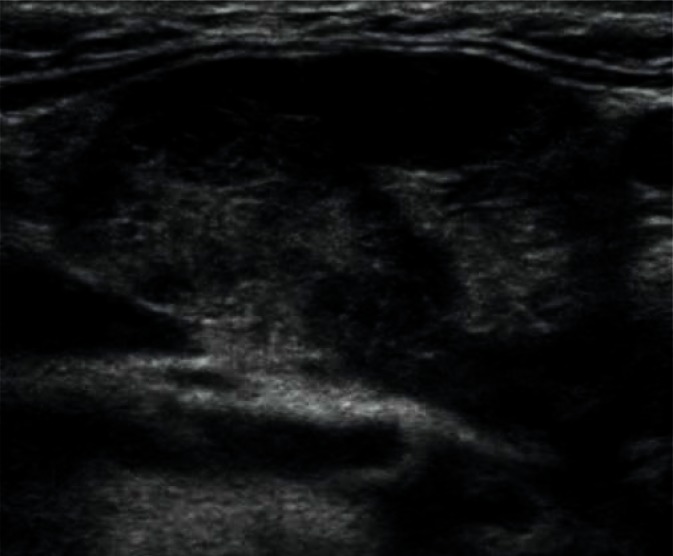

Fig. 12.

Submandibular gland in Sjögren syndrome

Sialoses

Sialoses are salivary gland diseases of diverse and not fully explained etiology. They usually coexist with endocrine, metabolic or autonomic disorders. They manifest in salivary gland enlargement and increased parenchymal compactness (usually bilateral).

The ultrasonographic picture of sialoses (Fig. 13) is not very characteristic. Initially, only enlargement of the gland (usually the parotid gland) is observed. Later stages of the disease resemble chronic inflammation with signs of parenchymal fibrosis. Thickening of the walls of the dilated intraglandular ducts as well as secretory retention areas within the salivary lobules (analogous to the ‘orange tree’ in sialography) can be also occasionally observed. The echogenicity of the gland is significantly heterogeneous and increased, and the border between the parenchyma and the surrounding tissues gradually becomes blurred(1, 3, 26).

Fig. 13.

A typical picture of parotid sialosis with fibrotic parenchymal bands

Benign tumors of the salivary glands

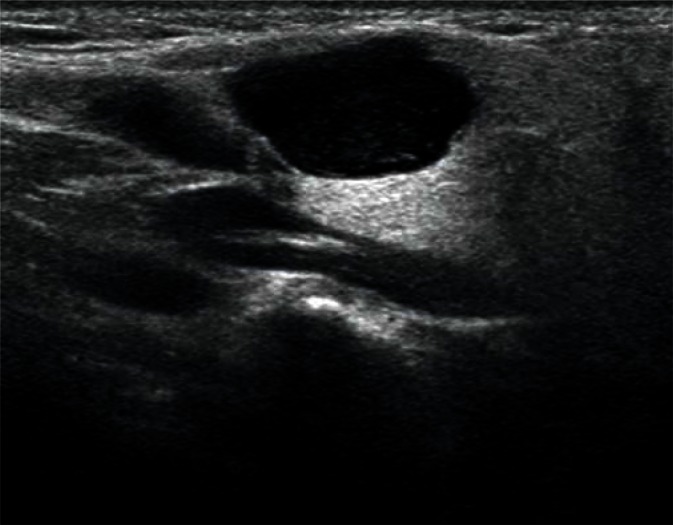

Adenomas are the most common benign tumors of the salivary gland (about 75% of all tumors). In ultrasonography, they usually appear as low-echoic focal lesions with smooth outlines and relatively clear borders. Such description of lesions seemingly provides little information for the diagnosis, but with their diameter of less than 1 cm, it is practically impossible to identify differences in their images. It is only with the passage of time and the growth of the tumor that some features (such as the polycyclic shape or degenerative lesions) characteristic for a certain type of adenoma occur (Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17). Multiple, synchronous occurrence in one or several salivary glands is the only typical feature of Warthin tumor (lymphatic cystadenoma)(27–29).

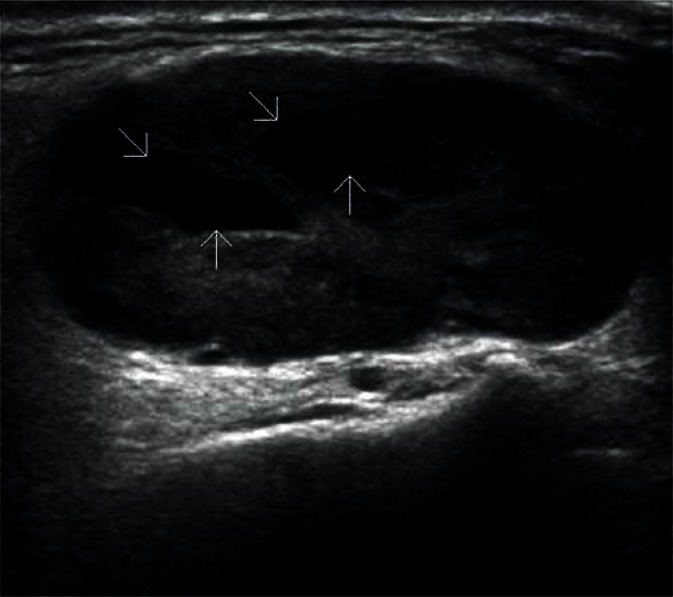

Fig. 14.

Lymphatic cystadenoma (Warthin tumor). Typical fluid spaces present in the tumor are indicated by arrows.

Fig. 15.

Warthin tumor with a visible cyst

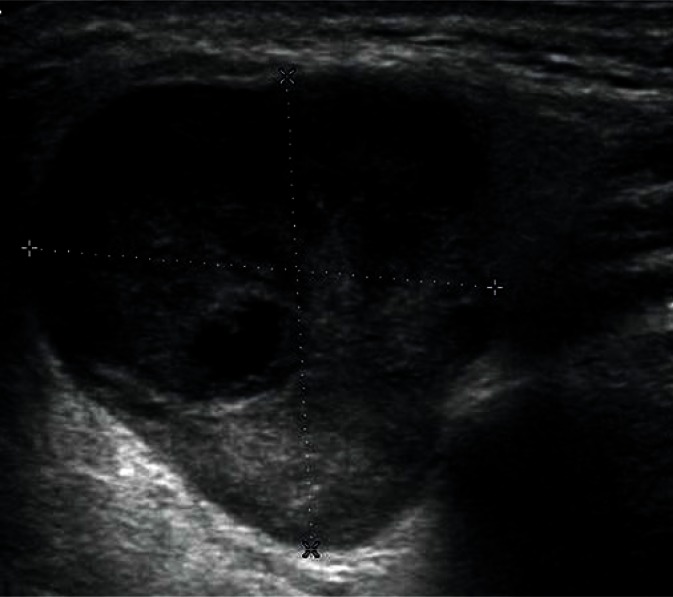

Fig. 16.

Pleomorphic adenoma (mixed tumor) in the parotid gland

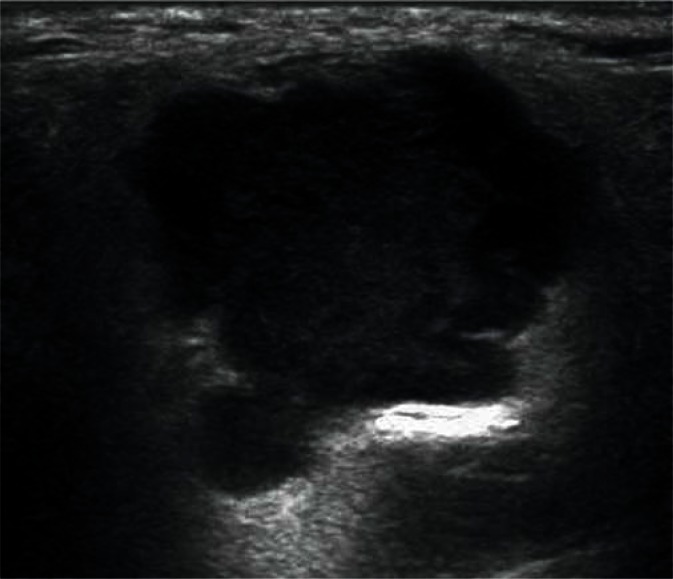

Fig. 17.

Multiple recurrence of pleomorphic adenoma. Recurrent foci are indicated by arrowheads.

For larger tumors, the high resolution of modern ultrasound devices as well as additional data obtained by means of Doppler techniques allow to identify the potential type of adenoma(30, 31).

However, this is of no importance from the clinical point of view as therapeutic management is the same for all benign tumors of the salivary glands. The preoperative diagnosis of the type of tumor is considered valid only if based on cytological assessment of material obtained using ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common tumor of the salivary glands (60–70%), which is usually detected in the parotid gland (60–70% of locations; Table 1)(13, 14, 32, 33).

Tab. 1.

Incidence and location of the most common benign tumors of the salivary glands

| Incidence | Location | |

|---|---|---|

| Mixed tumor | 70–80% of all benign tumors of the salivary glands | parotid gland in 60–90% of cases |

| Warthin tumor | 5–10% of all benign tumors of the salivary glands | multifocal in 60% of cases |

Large size and location of the tumor may affect assessment accuracy. Tumors with a diameter of more than 3–4 cm located in the deep lobe of the parotid gland often require the use of other imaging techniques (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography)(3, 34).

Malignant tumors of the salivary glands

Salivary gland malignancies are much less common than benign tumors (approximately 10% of all tumors), and the following regularity is observed: the smaller the salivary gland the lower the risk of tumor, but the higher the risk of malignancy. The most common malignant tumors of the salivary glands include adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas and undifferentiated carcinomas(1, 35).

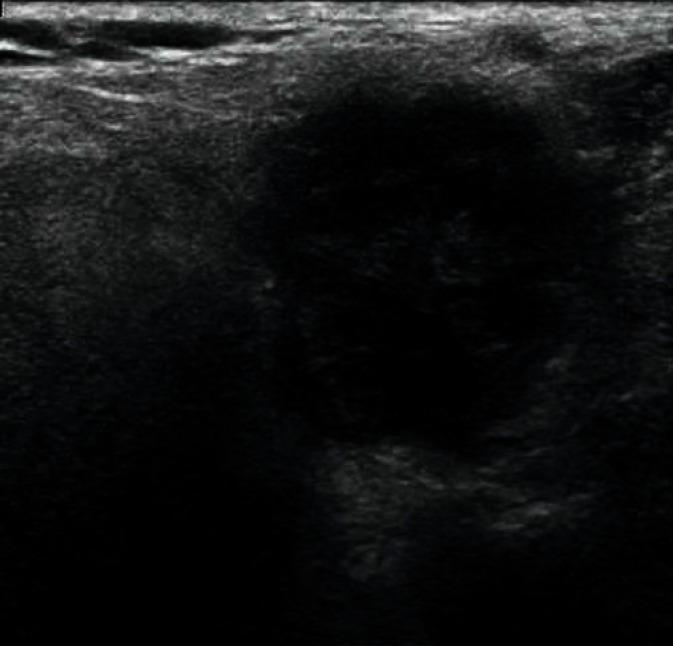

In ultrasonography, salivary cancers (Figs. 18, 19) appear as heterogeneously echogenic with uneven, blurred borders. Additionally, the spread of the tumor beyond the gland and invasion of adjacent structures may be observed. It should be noted that malignancies have higher growth dynamics and reach the size typical of a several-year adenoma in a shorter time. Due to regressive changes, which occur in malignant tumors earlier than in most adenomas, small salivary gland tumors already containing degenerative lesions are more suspicious of malignancy. Benign lymphatic cystadenoma (Warthin tumor) with a large cystic component and accompanying inflammatory processes represents a moajor problem in tumor differentiation based on ultrasound. Their image most resembles salivary cancers, and the increased blood flow associated with inflammation often contributes to misdiagnosis(27, 29, 36, 37).

Fig. 18.

Poorly differentiated carcinoma of the parotid gland – hypoechoic focus with blurred borders

Fig. 19.

Focus of adenocarcinoma of the parotid gland

The dominant fluid-filled spaces in some of the Warthin tumors also account for a misdiagnosed salivary gland cyst. It should also be noted that a several-year pleomorphic adenoma or its recurrence after non-radical excision can transform into a malignant form, therefore it seems justified to assess the nature of the tumor based on cytological findings in the first place. An ultrasonographist can determine the size, shape, location and the direction of infiltration of the adjacent tissues as well as the presence and characteristics of satellite lymph nodes(3, 38).

Other focal lesions found in the salivary glands

Other focal lesions found in the salivary glands include cysts and intraglandular lymph nodes affected by inflammation or neoplasms (Figs. 20, 21). In the case of cysts of the salivary glands, the obtained images are quite clear and the diagnosis does not pose much difficulty. Abnormal lymph nodes cause much more difficulty, and the identification of other lymph nodes in this region may prove useful in the diagnosis(2, 6, 7).

Fig. 20.

Retention cyst in the parotid gland

Fig. 21.

Affected intraglandular parotid lymph nodes in lymphocytic leukemia

It should also be noted that tumors originating from adipose tissue, nerves or vessels can also occur. The appearance of lipomas and neuromas located within the salivary glands corresponds to those located in other parts of the body, while the diagnosis of vascular malformations and hemangiomas is more complex.

For malformations, the problem mainly concerns the submandibular glands with the facial artery running through their parenchyma. Different anatomical variations are observed in the course of the artery, which, in some of the patients, may be significantly dilated and tortuous in the intraglandular segment. In extreme cases, it should be differentiated from vascular malformations. There are, by definition, many types of hemangiomas. There are differences between venous arterial and lymphatic hemangiomas. The picture of cystic hygroma is most surprising. It usually appears as a very extensive lesion resembling a multi-chambered cyst divided by multiple thin walls, and the salivary glands are only one of the many involved tissues of the neck. All cases of tumors of vascular origin require the use of all Doppler options, which allow to determine the extent of lesions as well as the intensity and the type of blood flow. In some cases, it is possible to identify the major vessels supplying the hemangioma (for embolization purposes) or detect arteriovenous fistulas(1, 3, 34).

Post-traumatic lesions of the salivary glands

Severe injuries in the region of parotid and submandibular salivary glands can cause intraglandular and subcapsular hematomas. The extravasated blood penetrates in between the lobules of the gland, forming a relatively typical picture of irregular anechoic spaces with a tendency towards changes in the echogenicity occurring over time. This is due to natural phenomena associated with blood clotting and resorption of the lesion(1, 3, 6).

However, the hematoma may turn into salivary abscess as a result of superinfection. This complication is very serious, therefore disease monitoring becomes another role of ultrasonography. Early detection of abscess and a change in the treatment allow to avoid further complications. The formation of an abscess in the salivary gland produces a non-specific image (Fig. 22), but as with most inflammatory processes, several characteristic elements can be found, such as enlarged satellite lymph nodes or increased blood flow in the dilated vessels surrounding the irregular anechoic and hypoechoic spaces(1, 3, 19).

Fig. 22.

An abscess in the right parotid parenchyma (indicated by arrowheads)

Furthermore, other characteristic changes may occur in the salivary gland as a result of injury. These include post-traumatic foreign bodies stuck in the glandular parenchyma. Ultrasound is of particular importance in cases of non-metallic fragments, which cannot be visualized using X-rays. They are clearly visible and easy to locate in the ultrasound image. This type of examination can be performed prior to elective wound revision or even intraoperatively(1, 39).

Ultrasound description(4)

A report from an ultrasound examination should include the date, patients’ data as well information on the device used and transducer parameters.

The description should begin with the assessment of the size and echogenicity of the individual glands. In the case of visualized intra- and extraglandular ducts (indicating secretory retention), their maximum diameter values should be reported and, if deposits are found in their lumen, their size should also be reported.

If focal lesions are detected, their maximum size (in three planes), echogenicity and structure (solid, cystic or mixed) should be reported. It is also important to describe the borders of the lesions with the surrounding glandular parenchyma or other tissues. This should be followed by their accurate location, using e.g. landmarks, such as the core, the angle or the branch of the mandible, the mastoid process or characteristic muscles or vessels.

An assessment of parenchymal blood flow in the inflammatory processes as well as the characteristics of the vasculature of focal lesions are another element of description.

The final part of description should include information on the surrounding lymph nodes and, in the case of tumors, an assessment of all accessible neck lymph nodes.

Photographical documentation of all described morphological changes should be an integral part of ultrasonographic examination.

Summary

Recent technical developments in the field of ultrasonography have contributed to new diagnostic possibilities. Improvement in the quality of picture due to both, increased resolution and the expansion of the real-time image by including elements based on Doppler techniques, provide ultrasonographists with an increasingly improved tool. This reinforces the already high position of diagnostic ultrasonography in the assessment of salivary glands among other imaging methods.

The new experience gained through the use of modern equipment allows us to offer clinicians more comprehensive answers to questions from their daily practice. Standardization of ultrasound diagnostics aims to ensure the same level of satisfaction with the cooperation of clinicians and diagnosticians in all centers as well as to facilitate the communication between different centers, where patients have their diagnostic tests performed.

The presented paper goes beyond the limits of previously published Standards of the Polish Ultrasound Society for the ultrasound assessment of salivary glands – by discussing different aspects of images obtained in different clinical cases. Therefore, it rather represents a kind of illustrated guide on salivary gland pathologies on ultrasonographic images.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not report any financial or personal connections with other persons or organizations, which might negatively affect the contents of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Kamble RC, Joshi AN, Mestry PJ. Ultrasound characterization of salivary lesions. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Clin. 2013;5:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yousem DM, Kraut MA, Chalian AA. Major salivary gland imaging. Radiology. 2000;216:19–29. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bialek EJ, Jakubowski W, Zajkowski P, Szopinski KT, Osmolski A. US of the major salivary glands: anatomy and spatial relationships, pathologic conditions, and pitfalls. Radiographics. 2006;26:745–763. doi: 10.1148/rg.263055024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zajkowski P. Badanie USG ślinianek. In: Jakubowski W, editor. Standardy badań ultrasonograficznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego. Warszawa–Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2011. pp. 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koischwitz D, Gritzmann N. Ultrasound of the neck. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38:1029–1045. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gritzmann N, Rettenbacher T, Hollerweger A, Macheiner P, Hübner E. Sonography of the salivary glands. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:964–975. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahuja AT, Ying M. Sonographic evaluation of cervical lymph nodes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1691–1699. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.5.01841691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz P, Hartl DM, Guerre A. Clinical ultrasound of the salivary glands. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009;42:973–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dost P, Kaiser S. Ultrasonographic biometry in salivary glands. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1997;23:1299–1303. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(97)00152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gritzmann N. Sonography of the salivary glands. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:161–166. doi: 10.2214/ajr.153.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salaffi F, Carotti M, Argalia G, Salera D, Giuseppetti GM, Grassi W. [Usefulness of ultrasonography and color Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of major salivary gland diseases] Reumatismo. 2006;58:138–156. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2006.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zengel P, Schrötzlmair F, Reichel C, Paprottka P, Clevert DA. Sonography: the leading diagnostic tool for diseases of the salivary glands. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2013;34:196–203. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho HW, Kim J, Choi J, Choi HS, Kim ES, Kim S, et al. Sonographically guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of major salivary gland masses: a review of 245 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1160–1163. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan YL, Chan SC, Chen YL, Cheung YC, Lui KW, Wong HF, et al. Ultrasonography-guided core-needle biopsy of parotid gland masses. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1608–1612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terraz S, Poletti PA, Dulguerov P, Dfouni N, Becker CD, Marchal F, et al. How reliable is sonography in the assessment of sialolithiasis? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:W104–W109. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loizides A, Gruber H. Reliability of sonography in the assessment of sialolithiasis: is the fishnet mesh too small? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:W119. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ching ASC, Ahuja AT. High-resolution sonography of the submandibular space: anatomy and abnormalities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:703–708. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.3.1790703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatty MA, Piggot TA, Soames JV, McLean NR. Chronic non-specific parotid sialadenitis. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51:517–521. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1997.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viselner G, van der Byl G, Maira A, Merico V, Draghi F. Parotid abscess: mini-pictorial essay. J Ultrasound. 2013;16:11–15. doi: 10.1007/s40477-013-0006-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nozaki H, Harasawa A, Hara H, Kohno A, Shigeta A. Ultrasonographic features of recurrent parotitis in childhood. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:98–100. doi: 10.1007/BF02020162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu M, Ußmüller J, Donath K, Yoshiura K, Ban S, Kanda S, et al. Sonographic analysis of recurrent parotitis in children: a comparative study with sialographic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:606–615. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sa'do B, Yoshiura K, Yuasa K, Ariji Y, Kanda S, Oka M, et al. Multimodality imaging of cervicofacial actinomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:772–782. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Zhang S, He J, Hu F, Liu H, Li J, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of major salivary glands in primary Sjögren's syndrome: comparison of two scoring systems. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:1680–1687. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milic V, Petrovic R, Boricic I, Radunovic G, Marinkovic-Eric J, Jeremic P, et al. Ultrasonography of major salivary glands could be an alternative tool to sialoscintigraphy in the American-European classification criteria for primary Sjögren's syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1081–1085. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carotti M, Salaffi F, Manganelli P, Argalia G. Ultrasonography and colour Doppler sonography of salivary glands in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s100670170068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merlo C, Bohl L, Carda C, Gómez de Ferraris ME, Carranza M. Parotid sialosis: morphometrical analysis of the glandular parenchyme and stroma among diabetic and alcoholic patients. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:10–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshiura K, Miwa K, Yuasa K, Tokumori K, Kanda S, Higuchi Y, et al. Ultrasonographic texture characterization of salivary and neck masses using two-dimensional gray-scale clustering. Dentomaxillofac Radiology. 1997;26:332–336. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu M, Ußmüller J, Hartwein J, Donath K. A comparative study of sonographic and histopathologic findings of tumorous lesions in the parotid gland. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:723–737. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dumitriu D, Dudea S, Botar-Jid C, Băciuţ M, Băciuţ G. Real-time sonoelastography of major salivary gland tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W924–W930. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinoli C, Derchi LE, Solbiati L, Rizzatto G, Silvestri E, Giannoni M. Color Doppler sonography of salivary glands. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:933–941. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.4.8092039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinhart H, Zenk J, Sprang K, Bozzato A, Iro H. Contrast-enhanced color Doppler sonography of parotid gland tumors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:344–348. doi: 10.1007/s00405-002-0579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dumitriu D, Dudea SM, Botar-Jid C, Băciuţ G. Ultrasonographic and sonoelastographic features of pleomorphic adenomas of the salivary glands. Med Ultrason. 2010;12:175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Białek EJ, Jakubowski W, Karpińska G. Role of ultrasonography in diagnosis and differentiation of pleomorphic adenomas: work in progress. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:929–933. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee YY, Wong KT, King AD, Ahuja AT. Imaging of salivary gland tumours. Eur J Radiol. 2008;66:419–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Khateeb SM, Abou-Khalaf AE, Farid MM, Nassef MA. A prospective study of three diagnostic sonographic methods in differentiation between benign and malignant salivary gland tumours. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2011;40:476–485. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/18407834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howlett DC. High resolution ultrasound assessment of the parotid gland. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:271–277. doi: 10.1259/bjr/33081866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong X, Xiong P, Liu S, Xu Q, Chen Y. Ultrasonographic appearances of mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the salivary glands. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welkoborsky HJ. Aktuelle Aspekte der Ultraschalluntersuchung der Speicheldrüsen. HNO. 2011;59:155–165. doi: 10.1007/s00106-010-2217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gritzmann N, Hollerweger A, Macheiner P, Rettenbacher T. Sonography of soft tissue masses of the neck. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30:356–373. doi: 10.1002/jcu.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]