Abstract

Objectives

A promising curative approach for HIV is to use designer endonucleases that bind and cleave specific target sequences within latent genomes, resulting in mutations that render the virus replication incompetent. We developed a mathematical model to describe the expression and activity of endonucleases delivered to HIV-infected cells using engineered viral vectors in order to guide dose selection and predict therapeutic outcomes.

Methods

We developed a mechanistic model that predicts the number of transgene copies expressed at a given dose in individual target cells from fluorescence of a reporter gene. We fitted the model to flow cytometry datasets to determine the optimal vector serotype, promoter and dose required to achieve maximum expression.

Results

We showed that our model provides a more accurate measure of transduction efficiency compared with gating-based methods, which underestimate the percentage of cells expressing reporter genes. We identified that gene expression follows a sigmoid dose–response relationship and that the level of gene expression saturation depends on vector serotype and promoter. We also demonstrated that significant bottlenecks exist at the level of viral uptake and gene expression: only ∼1 in 220 added vectors enter a cell and, of these, depending on the dose and promoter used, between 1 in 15 and 1 in 1500 express transgene.

Conclusions

Our model provides a quantitative method of dose selection and optimization that can be readily applied to a wide range of other gene therapy applications. Reducing bottlenecks in delivery will be key to reducing the number of doses required for a functional cure.

Introduction

HIV exerts a tremendous disease burden worldwide and a cure has remained elusive. Although viral replication can be suppressed using HAART drug regimens, plasma viral load rebounds rapidly upon treatment cessation.1 A major barrier to achieving a cure for HIV lies in the persistence of non-replicating integrated proviral HIV DNA, residing mainly in resting memory CD4+ T cells. Although <1 in 106 resting CD4+ T cells is thought to harbour latent HIV provirus, viral reactivation from this latent pool is responsible for the rapid rebound seen following HAART interruption. Based on the 44 month clearance half-life of the latent reservoir,2 it is estimated that a majority of HIV-infected individuals will require life-long therapy.3 However, it has been suggested that a functional cure can be achieved if the size of the reservoir is reduced ∼10 000-fold such that the likelihood of viral reactivation is significantly diminished.4,5

One approach aimed at depleting the latent viral reservoir involves the use of targeted gene editing techniques with engineered DNA cleavage enzymes.6–9 These enzymes, which include homing endonucleases, zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) and CRISPR/Cas9, are designed to bind and induce double-strand breaks in specific sequences within latent viral genomes that persist even after decades of suppressive antiviral therapy. Since the process of DNA repair through non-homologous end joining is error prone,10 repeated break–repair cycles eventually lead to a replication-incompetent virus and eliminate the potential for HIV reactivation within a latently infected cell. This approach has shown promise in vitro and in vivo.11–15 Terminal mutation of a sufficient proportion of cells may lead to a functional cure in which the probability of HIV recrudescence is extremely low.4,5

Many methods are in development for the delivery of therapeutic enzymes to target cells including engineered viral vectors and other non-viral delivery systems.8,16 Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors have been safely used to deliver transgenes in a number of animal models and clinical trials.17,18 AAV serotypes vary widely in terms of tissue tropism, transduction efficiency and packaging capacity. For example, self-complementary AAV (scAAV) vectors achieve high transduction efficiencies in multiple cell types compared with single-stranded AAV, but have smaller packaging capacity.19 The choice of promoter driving transgene expression is also an important consideration and can place additional limitations on packaging. Optimization of transgene delivery is therefore a crucial step in the design of these therapeutic approaches20—it involves the selection of an appropriate vector, promoter and dosage21 to maximize cleavage of target sites with minimal toxicity. Delivery efficiency is typically assessed by measuring the expression of a fluorescent reporter gene and high-throughput methods such as flow cytometry can be used to screen different vectors and promoters. However, current methods assess delivery in terms of percentage transduction and do not give a precise measure of the number of transgene copies delivered and expressed per cell. This may represent a critical omission, as high intracellular cleavage enzyme levels may be required to ensure terminal cleavage of integrated viral DNA.

Here, we describe a mechanistic mathematical model of gene therapy that focuses on the delivery and expression of reporter genes transported by viral vectors to target cells. We used fluorescence histograms from flow cytometry experiments to infer the number of transgene copies expressed in single cells at a given dose. We used this approach to determine which vector serotypes, promoters and dose ranges would optimize the expression of transgenes and identify the magnitude of bottlenecks that occur at viral uptake and gene expression. Finally, we predicted the clinical efficacy of these gene therapy platforms using a range of possible parameters determined from our model. While our model focuses on viral delivery vectors for the cure of HIV-1, its parameters are easily identified and its assumptions are readily verified. This pharmacodynamics model can therefore be easily adapted and fitted to data from other gene therapy platforms and should be included as an optimization tool for gene therapy protocols in the clinic.

Materials and methods

Quantification of gene expression using flow cytometry

We fitted our models to data obtained from experiments previously described in De Silva Feelixge et al.21 as well as a novel dataset of vector delivery. In these experiments, scAAV vectors were optimized for delivery of ZFNs to the HIV-permissive SupT1 CD4+ T cell line. Expression of fluorescent reporter gene(s) was quantified by flow cytometry 72 h post-transduction. Unless stated otherwise, experiments were performed with a total of 5 × 104 SupT1 cells in 24-well plates with 0.5 mL of RPMI containing 10% FBS and varying viral dose expressed as the ratio of vector genomes added per target cell (vg/cell). All AAV vector stocks were quantified by quantitative PCR according to the method of Aurnhammer et al.22

Serotype screen

Eight different scAAV serotypes (AAV1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9) were generated with the hCMV promoter driving GFP expression. Delivery in SupT1 cells was compared across AAV serotypes by quantification of fluorescence. Viral stocks were produced by polyethyleneimine transfection of HEK293 cells and purified by iodixanol gradient separation as described in Choi et al.,23 concentrated into PBS using an Amicon Ultra-15 column (EMD Millipore) and stored at −80°C. Cells were transduced at three different doses (2 × 104, 1 × 105 and 5 × 105 vg/cell) (Dataset A).

Promoter screen

scAAV1 vectors were generated with eight different promoter constructs (hCMV, MSCV, SFFV, shortCMV, MND, EFS, CMV173 and CMV113) in order to select a promoter that would maximize expression of transgene. Viral stocks were purified as described above. SupT1 cells were transduced at three different doses (2 × 104, 1 × 105 and 5 × 105 vg/cell) and GFP was used as a reporter (Dataset B).

Co-transduction assay

In order to assess the potential for delivery of multiple enzymes or enzyme subunits, SupT1 cells were transduced at different doses with unpurified scAAV1 vectors (viral lysates clarified using a 0.22 μm filter) expressing either GFP or mCherry reporter genes with the EFS promoter driving expression. A high-dose experiment was performed at doses of 5 × 104, 1 × 105 and 1.5 × 105 vg/cell for each reporter and a low-dose experiment at 5 × 103, 1 × 104, 5 × 104 and 1 × 105 vg/cell for each reporter. Cells were treated with either scAAV1-GFP only, scAAV1-mCherry only or both mixed in a 1 : 1 ratio (Dataset C).

AAV DNA uptake and expression

In order to evaluate possible bottlenecks in the pathway to gene expression (at the level of vector delivery versus gene expression), we analysed the levels of cellular virus uptake and transgene expression. SupT1 cells were incubated with scAAV1 vectors expressing GFP and cells were analysed for virus uptake at 24 h post-transduction and transgene expressions at 72 h post-transduction. For uptake analysis, cells were treated with AAV vectors using the CMV and EFS promoters at a dose of 1 × 104, 1 × 105 and 1 × 106 vg/cell. DNA was extracted from cells after being washed three times with PBS and vector copies per cell were quantified by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) using primers and probes specific for GFP24 and the housekeeping gene RPP30. For transgene expression analysis, cells were treated with AAV vectors using the CMV, EFS and MND promoters at six doses between 103 and 106 vg/cell. Levels of transgene expression were analysed by flow cytometry at 72 h post-transduction (Dataset D).

AAV and ZFN toxicity assay

In this experiment, 2.5 × 105 SupT1 cells were treated with scAAV1 vectors expressing ZFNs targeting the pol gene of HIV at a total dose of 2 × 104 or 1 × 105 vg/cell. Vectors contained one of four different ZFN pairs (1–4) delivered as separate subunits (e.g. 1A/1B, 2A/2B, etc.). In addition, two mismatched subunits were used as controls (1A/4A and 1B/4A). At 72 h post-transduction, cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI; Invitrogen) and V450-Annexin V (BD Biosciences) and analysed by flow cytometry at wavelengths corresponding to the PE-Cy5-A and Pacific Blue fluorophores, respectively. As a positive control for apoptosis, cells were treated with 20 μM camptothecin for 4–6 h prior to analysis (Dataset E).

Data import and processing

Raw flow datasets were imported and analysed in R.25 All flow data were imported and visualized using the flowCore26 and flowViz27 packages and filtered for debris using functions from the OpenCyto package.28 Clustering for toxicity data (Dataset E) was performed using the flowClust package,29 and the population of untreated cells was used to construct a prior distribution. See Supplementary data (available at JAC Online) for more details about pre-processing and clustering methods.

Modelling AAV-mediated transgene delivery, expression and toxicity

We developed a mechanistic mathematical model that relates vector dosage to gene expression measured in terms of fluorescence intensity. We first assumed that the mean number of vectors that achieve expression of transgene per cell (v) is a function of the input dose (vector genomes added per cell, m). Out of 10 competing functions (see Supplementary Methods and Table S1), the best fit was obtained with a sigmoid dose–response curve (equation 1). In the equation, t is the upper limit of gene expression (fluorescence); c is the half-maximal dose (EC50) and h is the Hill coefficient that determines the slope in the linear portion of the curve:

| (1) |

The number of vectors achieving transgene expression in target cells at a desired dose is then determined by a Poisson distribution with rate v, where the probability that a randomly selected cell contains k gene-expressing vectors is given by equation (2):

| (2) |

Finally, the fluorescence of a single cell containing k gene-expressing vectors is given by equation (3) (see Supplementary Methods for details of model selection), where f is the fluorescence due to a single delivered vector, f0 is the background fluorescence of an uninfected cell and n is a constant that determines the amplification of fluorescence within the cell due to gene expression from more than a single vector. Values of f0 in the model were drawn from the fluorescence distribution of untreated cells in each experiment:

| (3) |

We assumed that each expressed transgene copy is associated with a certain amount of fluorescent intensity that can be drawn from a normal distribution, . In experiments involving the delivery of two different molecules at once (e.g. ZFN subunits delivered in separated vectors), the amount of co-transduction is measured using two reporters delivered separately. In this case, the fluorescence of a single cell expressing k1 copies of reporter 1 and k2 copies of reporter 2 is given by where , , and the correlation between reporters 1 and 2 is unknown parameter . We assumed that the correlation between reporters was constant across vector dosages.

To determine whether the use of AAV vectors produces a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect, we fitted a standard dose–response curve (equation 4) to two measures of cell death: percentage of cells that stained positive for PI or Annexin V and amount of cellular debris produced. The proportion of apoptotic cells or debris pd is a function of input dose m, half-maximal toxicity c1 and Hill coefficient h1:

| (4) |

Model fitting and parameter estimation

We fitted the model by comparing histograms of predicted fluorescence to observed data and selected the parameter set that minimized the average residual sum of square errors (RSS; equation 5) across all doses. Fluorescence values were log-converted and histograms were plotted with bins spanning 0–6 in increments of 0.1. This range and resolution was found to be optimal for capturing differences between predicted histograms over a wide range of doses:

| (5) |

Optimization, fitting and data visualization were performed using R.25 To quantify the uncertainty associated with our parameter estimates, we obtained 95% CIs for each parameter by performing bootstrapping with 100 replicates.

Parameter estimation through rectangular gating

Traditional methods of assessing transduction efficiency with flow cytometry typically involve manually drawing rectangular gates on fluorescence channels. Untreated samples are used to set thresholds and cells with fluorescence values above these thresholds are marked as positive, i.e. transduced and expressing transgene. We compared our model's predictions of percentage transduction with this method by drawing a rectangular gate (Supplementary Methods) on debris-filtered, log-transformed fluorescence histograms for Dataset B (promoter screen) and determined the percentage of flow events lying above the threshold. Then, since P(0) = e−v (from equation 2), we computed the value of v at each dose and fitted a dose–response curve (equation 1) to these points to obtain estimates of delivery parameters t, c and h. We then used the histogram fitting technique described above to estimate fluorescence parameters while keeping the delivery parameters fixed and compared RSS scores of best-fit histograms from both methods.

Predicting endonuclease-mediated disruption of integrated provirus

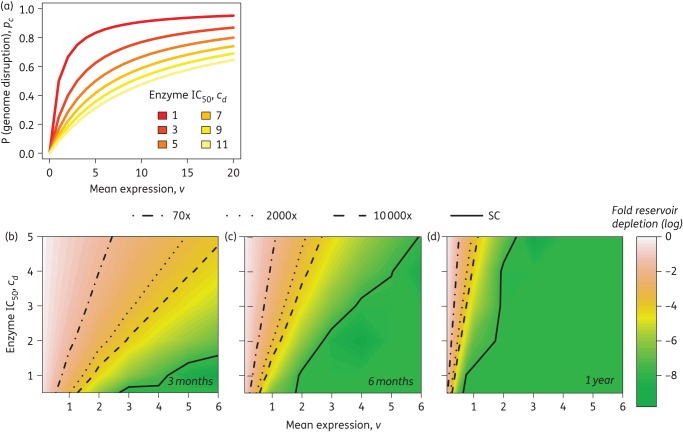

We hypothesized that the probability of cleavage (pc) or disruption of an integrated provirus genome would be a function of the number of endonuclease-bearing transgenes delivered and expressed (d) within the target cell, with cd = the value of d at which there is a 50% probability of genome disruption:

| (6) |

The number of cells with disrupted genomes after a single dose of endonuclease therapy is given by a binomial distribution , where N is the number of susceptible cells.

Therapeutic simulations of multiple sequential doses

Starting with N0 latently infected cells and assuming that each cell contains a single copy of the provirus, and that there is no development of resistance to the endonuclease, we performed a Monte Carlo simulation to determine the number of doses required to: (a) disrupt all integrated viral genomes; (b) disrupt enough of the reservoir to prevent rebound (‘functional cure’); and (c) delay time to recrudescence to a median of 1 year. For (b), we used the Hill et al.4 estimate that a 10 000-fold reduction in the reservoir would be required to prevent rebound altogether. For (c), we determined the number of doses required to achieve 2000- and 70-fold reductions in reservoir size, which are the estimates for a 1 year delay in rebound from Hill et al.4 and Pinkevych et al.,5 respectively.

Results

Increased vector dosage leads to higher gene expression

The effectiveness of transgene delivery was quantified by measuring the expression of a fluorescent reporter gene (GFP) using flow cytometry (Figure S1). With the exception of AAV4, gene expression was found to increase with dose intensification for all vector serotypes and promoters (Figure 1), indicated by increases in mean fluorescence intensity (mfi; Figure S2). Averaged across promoters, mfi increases relative to control (±1 SD) were 5.33 ± 2.92-, 19.59 ± 12.63- and 68.96 ± 44.43-fold at doses of 20 000, 100 000 and 500 000, respectively. Averaged across serotypes, these increases were 1.66 ± 1.03-, 4.52 ± 4.80- and 20.12 ± 32.68-fold at the same doses.

Figure 1.

Increased dose leads to higher gene expression at 72 h post-transduction for all vectors (a) and promoters (b), demonstrated by a shift to the right of GFP fluorescence intensity histograms. This corresponds to an increase in the mean fluorescence intensity (Figure S2). This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the printed version of JAC.

The mathematical model achieves close fit for all delivery vectors and promoters and predicts quantitative gene expression at all doses

We developed and validated a mechanistic model of gene expression that relates AAV vector dosage to fluorescence of SupT1 cells expressing reporter genes. We compared a number of competing models of vector-based delivery (Table S1) and found that a standard three-parameter dose–response curve gave the lowest average test error across samples (Figure S3). Model-derived and empirical fluorescence histograms were superimposed (Figure 2a) and showed close agreement (low RSS) in all experimental datasets. Fixing the slope of the dose–response curve in equation (1) (h = 1) gave improved fits for the serotype and promoter datasets (Datasets A and B, respectively). Some serotypes had little to no expression (AAV4, 7, 8 and 9) and the parameters for these vectors were non-identifiable. In all other cases, we were able to obtain robust parameter estimates with narrow CIs (Tables 1 and 2). We also validated our fits by comparing parameter estimates from Datasets B and D where some of the same promoters were used (Table 2, Figure S4 and Table S2) and confirmed that consistent parameter estimates are obtained across experimental replicates and dose ranges.

Figure 2.

Predicted delivery and expression of GFP 72 h post-transduction with various AAV serotypes and promoters. (a) Example of model fit with scAAV1 from serotype screen experiment: predicted histogram of fluorescence intensity (pink) overlaid on actual fluorescence histogram (blue). Model predictions of mean number of transgenes delivered and expressed per cell for scAAV serotypes 1–9 with hCMV promoter (b) and various scAAV1 promoter constructs (d). Percentage of untransduced cells at different doses (c and e) for the serotype and promoter screen experiments, respectively. Vertical grey lines indicate doses used in experiments. Model parameter estimates are shown in Tables 1 and 2. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the printed version of JAC.

Table 1.

Model fit and parameter estimates: serotype screen

| Serotype | Mean RSS | Best-fit parameters (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | t | log c | ||||

| AAV1 | 0.001 | 50.25 (46.79, 53.73) | 0.4 (0.35, 0.43) | 1.42 (1.39, 1.53) | 4.47 (3.84, 4.85) | 5.46 (5.34, 5.49) |

| AAV2 | 0.002 | 56.81 (49.75, 59.67) | 0.55 (0.52, 0.59) | 2.27 (2.12, 2.36) | 2.00 (1.83, 2.19) | 4.95 (4.90, 5.04) |

| AAV4 | 0.001 | 46.39 (42.5, 50.76) | 2.17 (1.51, 5.71) | 2.75 (1.53, 7.12) | 3.81 (2.22, 8.46) | 14.34 (12.00, 18.94) |

| AAV5 | 0.001 | 56.56 (48.24, 59.28) | 0.43 (0.37, 0.49) | 1.39 (1.29, 1.62) | 3.65 (3.17, 4.16) | 6.05 (5.99, 6.13) |

| AAV6 | 0.003 | 55.85 (48.49, 58.66) | 0.45 (0.42, 0.50) | 1.99 (1.88, 2.08) | 6.65 (6.61, 9.17) | 5.68 (5.68, 5.85) |

| AAV7 | 0.001 | 57.23 (56.69, 62.9) | 0.45 (0.37, 0.54) | 12.50 (9.90, 13.67) | 3.60 (2.68, 4.41) | 6.73 (6.60, 6.91) |

| AAV8 | 0.003 | 49.10 (45.61, 53.79) | 6.98 (2.78, 11.85) | 4.83 (1.60, 9.65) | 14.55 (10.36, 19.25) | 13.44 (10.54, 18.35) |

| AAV9 | 0.002 | 43.30 (40.59, 47.62) | 7.83 (4.39, 11.61) | 3.77 (2.40, 8.44) | 2.32 (1.40, 6.54) | 9.50 (8.20, 13.48) |

RSS, residual sum of square errors; h = 1 (equation 1).

Parameters for AAV4, 7, 8 and 9 not identifiable.

Best-fit parameters are those that gave the minimum mean RSS across doses; 95% CI determined by bootstrapping.

Table 2.

Model parameter estimates: promoter screen

| Promoter | Mean RSS | Best-fit parameters (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | t | log c | ||||

| CMV113 | 0.001 | 55.99 (54.14, 58.88) | 0.45 (0.42, 0.49) | 1.61 (1.50, 1.64) | 5.14 (4.86, 5.67) | 5.49 (5.46, 5.57) |

| CMV173 | 0.001 | 48.20 (46.5, 50.4) | 0.38 (0.39, 0.50) | 1.69 (1.59, 1.70) | 4.24 (4.29, 5.13) | 5.41 (5.42, 5.52) |

| EFS | 0.002 | 60.24 (60.2, 66.54) | 0.51 (0.47, 0.53) | 2.00 (1.92, 2.02) | 7.30 (6.93, 7.83) | 5.27 (5.25, 5.33) |

| hCMV | 0.001 | 48.62 (46.82, 51.2) | 0.46 (0.39, 0.47) | 1.59 (1.52, 1.65) | 4.50 (4.14, 5.04) | 5.67 (5.64, 5.74) |

| MND | 0.002 | 65.56 (65.55, 73.29) | 0.49 (0.48, 0.53) | 2.03 (1.97, 2.05) | 6.54 (6.36, 7.21) | 5.19 (5.17, 5.27) |

| MSCV | 0.002 | 60.56 (60.39, 65.9) | 0.5 (0.47, 0.53) | 2.01 (1.93, 2.02) | 7.00 (6.67, 7.63) | 5.25 (5.22, 5.32) |

| sCMV | 0.001 | 56.06 (54.91, 59.19) | 0.47 (0.43, 0.48) | 1.71 (1.63, 1.73) | 6.43 (6.11, 6.89) | 5.30 (5.27, 5.36) |

| SFFV | 0.002 | 60.61 (60.34, 65.45) | 0.53 (0.49, 0.55) | 1.98 (1.88, 2.00) | 6.96 (6.5, 7.51) | 5.16 (5.15, 5.25) |

RSS, residual sum of square errors; h = 1 (equation 1).

Best-fit parameters are those that gave the minimum mean RSS across doses; 95% CI determined by bootstrapping.

The vast majority of input vectors do not lead to gene expression

Our results show that when using AAV vectors for the delivery of transgenes, only a small percentage of genomes successfully produce gene product in cells (Figure 2b and d). As a result, many cells are left untransduced even when optimal vectors (Figure 2c) and promoters (Figure 2e) are selected. Very high vector doses are required to transduce cells and produce detectable quantities of reporter proteins. At a dose of 500 000 vector genomes per cell, there is an average of one to five transgene copies expressed per cell, depending on the promoter (Figure 2d). Even at this high dose, ∼0.5% of target cells remain untransduced when the optimal serotype (AAV1, 2 or 6) and promoter (EFS, MND, SFFV or MSCV, Table 2) are used. If the input dose were to be increased further, the model predicts that the maximum average expression that can be achieved is approximately seven transgene copies. The model can therefore be used for dose selection by computing , where m is the dose required to achieve a desired fraction of untransduced cells (p0) and c and t are parameters corresponding to the AAV serotype and promoter chosen (from Tables 1 and 2).

The model outperforms manual gating in predicting transgene delivery and expression

We compared predictions from our model with traditional methods that rely on gating to determine percentage transduction. For each sample, we used the percentage of GFP-positive cells determined from a rectangular gating scheme (Figure S5) to compute the average number of expressed transgene copies (v) and fitted a dose–response curve. Predicted values of the expected number of expressed copies per cell obtained using rectangular gates were lower by 34%–74% (Figure 3) compared with predictions from our model. Histograms generated using these gating-based estimates also gave poorer fits compared with those obtained by learning all model parameters without gating for fluorescence (mean RSS across doses and promoters 0.0070 ± 0.0027 versus 0.0013 ± 0.0005; Table S3). Our results therefore suggest that gating-based methods underestimate the number of cells that are expressing the reporter gene at a given dose and that our model provides a more accurate estimate of percentage transduction at a given dose.

Figure 3.

Traditional gating methods underestimate transgene delivery and expression. Estimates of percentage transduction from rectangular gating were used to compute average transgene expression (copies per cell) for each promoter and dose for Dataset B. A dose–response curve was fitted to these values (dashed line) and compared with model predictions (solid line).

Bottlenecks occur at both vector entry and gene expression stages of transduction

We performed intracellular ddPCR-based viral DNA quantification at 24 h post-transduction at doses of 104, 105 and 106 in order to assess the efficiency of viral uptake. Our results show that viral uptake (GFP copies per cell) increases with dose and is not dependent on the promoter construct used (Figure 4a), with ∼1 in every 220 added genomes successfully entering the cell (Figure 4c). In contrast, the number of added genomes that go on to express transgene ranges from ∼1 in 180 000 to ∼1 in 4000, depending on the added dose and promoter construct used. A 10-fold increase in viral uptake translates to ∼2 additional copies expressed per cell (Figure 4b). We also showed above that the promoter plays a significant role in transgene expression and can lead to a doubling of copies expressed at a given dose. These results suggest that bottlenecks are present at various stages of transgene delivery from viral entry to gene transcription and translation.

Figure 4.

Comparing viral uptake and gene expression post-transduction. (a) Quantitation of viral uptake at 24 h post-transduction using ddPCR for scAAV1 vectors with either the hCMV or EFS promoter, n = 3 replicates per dose. (b) Predicted mean transgene expression at 72 h post-transduction (GFP copies/cell) as a function of mean viral uptake (log copies/cell). For fitted linear model, adjusted R2 = 0.998 and 0.879 and slope = 2.35 and 1.86 for hCMV and EFS promoters, respectively. Shaded band shows 95% CI for overall fit (both promoters) with a linear model. (c) Uptake and expression shown as a percentage of the number of genomes added demonstrate the large bottleneck at each step and the role of the promoter construct in enhancing transgene expression. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the printed version of JAC.

Model results suggest cumulative amplification of gene expression following delivery

In our model, the fluorescence per expressed transgene copy was assumed to be normally distributed with . The fitted parameters showed that the values of and were generally similar across serotypes and promoters (Tables 1 and 2) and only depended on the fluorophore used rather than vector or promoter. In both the serotype screen as well as the promoter screen where GFP was used, we obtained values between 43 and 73 and . In addition, the best-fit values of n ranging between 1.2 and 2 suggest that sequential amplification of gene expression occurs within single cells.

Correlations, heterogeneity and amplification in gene expression

We also conducted experiments involving the addition of more than one reporter at a time to assess whether multiple enzymes targeting different sites can be delivered with the same dose (Figure S6). Our model showed that signals from two fluorescent reporters (GFP and mCherry) are highly correlated, with a Pearson correlation coefficient >0.9 (Table S4). This suggests that cells expressing one reporter gene at a high level are more likely than average to also express the other at a high level. In this set of experiments, the Hill coefficient (h) was >1, suggesting a lower barrier to additional transgene expressions in a single cell upon initial transgene expression.

Low levels of AAV- and ZFN-induced cytotoxicity

We measured the levels of toxicity due to AAV and ZFNs by quantifying the expression of PI and Annexin V using flow cytometry. Our results show that AAV1-based vectors do not lead to a significant increase in cell death. In the GFP-only treatment, the percentage of dead cells was 4.35 ± 0.64% at a dose of 20 000 vg/cell and 4.58 ± 0.31% at a dose of 100 000 vg/cell (Figure S7). This rate of cell death was <1% higher than the control case (PI + Annexin V only, 3.76 ± 0.30%). ZFN-treated cells showed slightly increased levels of cell death ranging from 4.6% to 7.8%. In all cases, no clear mathematical dose–response (equation 4) in toxicity could be established (Figure S8).

Number of doses needed to achieve cure is dependent on delivery

Starting with an estimated reservoir size of 107 latently infected cells,30 assuming one integrated copy of HIV per cell, and no treatment resistance, we used Monte Carlo simulations (Figure S9) to determine the number of infected cells remaining after each dose with weekly dosing of AAV-delivered endonucleases (assuming that the enzyme is delivered as a single molecule). The probability of genome disruption pd depends on transgene expression (v) and the enzyme's potency is characterized by its IC50 (cd, transgene expression in copies per cell at which 50% of genomes are disrupted) (Figure 5a). We tested values of cd ranging between 0.5 and 5 and average transgene expression between 0.1 and 6 copies per cell (Figure5b–d). This broad range covers mutation and expression rates seen across multiple AAV-based gene therapy platforms that utilize ZFNs, megaTALs and CRISPRs.21,31–34 For example, we have shown previously21 that at a dose of 50 000 vg/cell, ZFNs targeting the HIV pol gene can produce mutations in up to 28% of integrated HIV proviruses and this can cause a significant decrease in the production of infectious virus. Based on our model (equation 1), we expect cells at this dose to contain an average of one to two expressed transgene copies. Then, we can calculate from equation (5) that we require 4–9 average expressed copies/cell to achieve disruption in 50% of genomes. Improvements in the technology over time could produce more potent enzymes with progressively lower cd values and vectors with higher v (average transgene expression) at lower doses.

Figure 5.

Genome disruption to achieve a cure. The probability of genome disruption increases with transgene expression in a dose-dependent manner (a). Enzyme potency is characterized by cd, the expression level at which there is a 50% probability of disruption of the latent provirus. Assuming weekly dosing and an initial reservoir size of 107 latently infected cells, the treatment duration required to achieve a sterilizing cure (SC; complete reservoir depletion), functional cure (≥10 000× depletion of the reservoir) or year-long delay in rebound (70× or 2000× depletion) will depend on both delivery and expression of transgene and enzyme potency (b–d). This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the printed version of JAC.

We found that with a highly effective enzyme (e.g. cd = 0.5), an average expression of ≥0.75 copies/cell would be needed to completely deplete the reservoir within a year (Figure 5d). With a weakly effective molecule (e.g. cd = 4), average transgene expression needs to be between 2 and 3 copies/cell to achieve complete reservoir depletion within a year of weekly treatments. To achieve this level of expression, we estimate a required ratio of ∼105 vg/cell depending on the AAV serotype and promoter used. If administered to the whole body in humans, we can compute the total dose required based on the total blood volume (TBV; 65–70 mL/kg body weight35) and total concentration of CD4+ T cells (200–700 cells/mm3 of blood36). Based on these ranges, the total required dose (TBV × CD4+ count × desired vg/cell) is between 1.3 and 4.9 × 1012 vg/kg body weight.

We also computed the number of doses required to achieve a functional cure, defined by Hill et al.4 as a 10 000-fold depletion of the reservoir, for different values of transgene expression and enzyme potency. Our results show (Figure 5b–d) that depending on the potency of the enzyme, a functional cure can be achieved as early as 3 months after therapy starts, provided every transduced cell expresses (on average) more than one transgene copy. We also computed the enzyme potencies and mean transgene expression levels that would be necessary to delay viral rebound by 1 year, based on two estimates of required reservoir depletion (2000-fold4 and 70-fold5).

Discussion

The development of targeted genome editing enzymes such as ZFNs, homing endonucleases, TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 represents a major leap forward in the search for a cure for persistent viral infections such as HIV, HBV and HSV. These enzymes have the potential to deplete the reservoir of non-replicating persistent viral forms. As these technologies mature, there is a growing need for computational tools to analyse and visualize the rich experimental datasets and also to make predictions that can guide future experiments by generating testable hypotheses. With this in mind, we developed a mathematical model that relates vector dosage to gene expression, predicts the distribution of fluorescence of single cells measured through flow cytometry and imputes the number of transgene copies delivered and expressed in individual cells. Finally, we linked gene expression to probability of genome disruption in order to estimate the number of doses that would be required to deplete the latent viral reservoir. With the exception of Prasad et al.37 and Wotherspoon et al.,38 who showed that delivery of transgenes follows a Poisson distribution, we are aware of no similar models for vector-mediated gene therapy that capture delivery, gene expression and efficacy with parameters informed by quantitative gene expression data.

By fitting our model to flow cytometry data from multiple experiments, we demonstrate that transgene delivery and expression plateaus at a level that depends on the vector serotype and promoter. The model's predicted values of delivery can be used to design an optimal delivery vector. This serves as an alternative to merely using the percentage of GFP-positive cells as a measure of transduction efficiency, which we showed significantly underestimates the actual number of transduced cells. We also implemented data-driven gating and filtering algorithms that rely on model-based clustering techniques,29,39 to remove operator-dependent differences in gating and improve the reproducibility of data.

The choice of promoter to drive transgene expression is an important consideration because delivery needs to be optimized while also maximizing the packaging capacity of the vector by utilizing the smallest promoter possible. This choice will also depend on the target cell type. Our model predicted that for SupT1 cells, the EFS and MND promoters give high levels of expression with >90% transduction at doses of 50 000 vg/cell, but the EFS promoter is much shorter (233 versus 347 bp) and is therefore a better choice for optimizing the 2.4 kb packaging limit of scAAV vectors.

Here, we focused on AAV vectors, which have now been tested in a number of in vitro16,40,41 and in vivo37 settings as well as a few clinical trials.18 A key finding from our model was that a large majority of AAV vectors do not lead to gene expression and that multiple bottlenecks exist between viral uptake, gene expression and cleavage of integrated provirus genomes. These bottlenecks encompass a variety of cellular processes including binding to cell surface receptors for viral entry, virus internalization, nuclear transport, viral capsid uncoating, genome degradation, proteolytic pathways and limitations due to cellular resources associated with each process. In addition, the bottlenecks may vary depending on the cell type or organ being targeted, the vector serotype used and the manufacturing and purification processes employed.

One such limiting process at the point of viral entry could be the presence of empty viral capsids that are produced at the time of generation of viral stocks—a phenomenon that has been reported in other studies with AAV.42,43 Empty capsids have been shown to reduce the efficiency of transduction,42 presumably by competing with functional vectors for receptor binding, internalization and intracellular trafficking. However, it is unclear what the implications are in a clinical setting: on the one hand, they have been shown to trigger a T cell response18 suggesting they may be immunogenic, but they may also serve as decoys for anti-AAV antibodies that are prevalent in the human population.44,45 There have been calls to establish standardized methods of preparation and purification of viral vectors.46 An alternative approach has been to engineer the capsid sequence such that it is prevented from entering cells that have already been transduced by the full vector.44 Improvement of gene therapy platforms will require identification and reduction of such bottlenecks and rate-limiting steps.

We also showed that when co-transduced with multiple reporters, expression of the reporters is highly correlated. This result implies that cells that have already been transduced by one vector have a better than random chance of being transduced by another. This has been observed in co-transduction experiments in other systems38 and highlights that heterogeneity in target cell quality, which makes some cells more permissive to transduction than others, is likely to be an important feature in determining the effectiveness of gene therapy approaches.

Although our model was fitted to data from a transformed cell line, our findings may be directly relevant to a wide range of gene therapy applications. For example, Sather et al.47 tested many of the same scAAV serotypes (1, 2, 5 and 8) on primary human CD4+ cells and mobilized CD34+ peripheral blood cells isolated from healthy adult donors and also found that doses ≥105 vg/cell were required to transduce >50% of cells. Similar results were obtained by Wang et al.,48 who screened AAV serotypes 2, 5, 6, 8 and 9 on CD8+ cells and found that AAV6 transduced cells at this level at doses of ≥3 × 105 vg/cell. Our prediction that transduced cells contain one to five copies of expressed transgene per cell at these doses may therefore be applicable in cell types that harbour latent HIV in vivo.

Dose selection is a key step in designing therapies and seeks to balance efficacy with toxicity. Due to the low frequency of latently infected cells in the body36 and because there is currently no way to specifically target these cells, engineered nucleases need to be delivered to all CD4+ cells. Our computation of the total dose required is based on a lower-bound estimate of the total number of CD4+ cells (since it does not include CD4+ cells within tissue). However, the computed dose is consistent with doses used in recent clinical trials employing AAVs for gene therapy in humans18,49–52 and non-human primates53 and lower than doses used in other animal models.54 With the exception of one case,18 no severe adverse events have been attributed to the study drug in the human trials above. However, the number of circulating lymphocytes is thought to constitute only 0.3%–0.5% of the total pool.55 To target the entire pool of CD4+ cells including tissue reservoirs, the total required dose would need to be ∼1014 vg/kg body weight. In our experiments, we found low levels of in vitro toxicity due to AAVs and ZFNs, but no clear dose-dependent effect could be observed with the dose ranges used. A more detailed analysis of toxicity will be required—this will allow calculation of a therapeutic index, which is vital to licensure and widespread implementation of gene therapies.

Previous models of gene therapy have predicted that the therapeutic outcome of targeted gene-editing molecules is likely to depend on delivery to target cells after removal by the immune system; the enzyme-DNA binding affinity; the effectiveness of cleavage; the degree of binding cooperativity between enzyme molecules and the number of transgenes delivered per vector.20 Our model captures most of these processes, but makes some simplifying assumptions. For example, we assume that mutation due to endonuclease treatment in a single cell immediately results in replication-incompetent provirus and we showed previously21 that treatment with ZFNs targeting HIV pol reduces the production of infectious virus by up to 64%. However, some endonuclease-generated mutations that have smaller effects may require multiple doses to render the virus replication incompetent. We also assumed that no treatment resistance develops, but we have recently demonstrated21 the emergence of resistant mutants following treatment with ZFNs. However, our results with multiple reporters showed that cells that have already been transduced by one vector have a better than random chance of being transduced by another. This suggests that multiplexing to target distinct HIV genomic regions may be a good way to prevent viral escape and to recleave resistant mutants. Our model also does not incorporate the probability of off-target cleavage.41 These are important considerations for therapy design and need to be incorporated in an expanded model as they are likely to impact our predictions of treatment outcomes.

In summary, we have developed a mechanistic model that predicts the outcome of vector-mediated gene therapy as a function of dosage. The model captures viral uptake, gene expression and cleavage of integrated provirus and identifies the bottlenecks associated with each step. We fitted the model to flow cytometry data from multiple experiments and obtained robust parameter estimates. We showed that the model outperforms gating-based methods in predicting the percentage of cells transduced by the vector. We showed that vector serotype, promoter and dose are key determinants of transgene expression and, along with enzyme potency, need to be optimized to maximize the probability of genome disruption with minimal cytotoxicity.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-supported Martin Delaney Collaboratory grant (grant number U19 AI096111) and in part by a developmental grant from the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (grant number P30 AI027757). H. L. P. was supported by a Research Scholarship from the Mary Gates Endowment for Students.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

We thank Bryan T. Mayer, Martine Aubert, Anna Wald, Daniel Reeves and Elizabeth R. Duke for helpful discussions and feedback on early versions of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Davey RT Jr, Bhat N, Yoder C et al. HIV-1 and T cell dynamics after interruption of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with a history of sustained viral suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 15109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siliciano JD, Kajdas J, Finzi D et al. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat Med 2003; 9: 727–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun TW, Moir S, Fauci AS. HIV reservoirs as obstacles and opportunities for an HIV cure. Nat Immunol 2015; 16: 584–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill AL, Rosenbloom DI, Fu F et al. Predicting the outcomes of treatment to eradicate the latent reservoir for HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 13475–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinkevych M, Cromer D, Tolstrup M et al. HIV reactivation from latency after treatment interruption occurs on average every 5–8 days—implications for HIV remission. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11: e1005000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiffer JT, Aubert M, Weber ND et al. Targeted DNA mutagenesis for the cure of chronic viral infections. J Virol 2012; 86: 8920–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone D, Kiem HP, Jerome KR. Targeted gene disruption to cure HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2013; 8: 217–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber ND, Aubert M, Dang CH et al. DNA cleavage enzymes for treatment of persistent viral infections: recent advances and the pathway forward. Virology 2014; 454–5: 353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF III. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol 2013; 31: 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell 2010; 40: 179–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu W, Kaminski R, Yang F et al. RNA-directed gene editing specifically eradicates latent and prevents new HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 11461–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebina H, Kanemura Y, Misawa N et al. A high excision potential of TALENs for integrated DNA of HIV-based lentiviral vector. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0120047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao HK, Gu Y, Diaz A et al. Use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system as an intracellular defense against HIV-1 infection in human cells. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qu X, Wang P, Ding D et al. Zinc-finger-nucleases mediate specific and efficient excision of HIV-1 proviral DNA from infected and latently infected human T cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41: 7771–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu W, Lei R, Le Duff Y et al. The CRISPR/Cas9 system inactivates latent HIV-1 proviral DNA. Retrovirology 2015; 12: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone D. Novel viral vector systems for gene therapy. Viruses 2010; 2: 1002–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asokan A, Schaffer DV, Samulski RJ. The AAV vector toolkit: poised at the clinical crossroads. Mol Ther 2012; 20: 699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathwani AC, Tuddenham EGD, Rangarajan S et al. Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 2357–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarty DM, Monahan PE, Samulski RJ. Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus (scAAV) vectors promote efficient transduction independently of DNA synthesis. Gene Ther 2001; 8: 1248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiffer JT, Swan DA, Stone D et al. Predictors of hepatitis B cure using gene therapy to deliver DNA cleavage enzymes: a mathematical modeling approach. PLoS Comput Biol 2013; 9: e1003131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Silva Feelixge HS, Stone D, Pietz HL et al. Detection of treatment-resistant infectious HIV after genome-directed antiviral endonuclease therapy. Antiviral Res 2016; 126: 90–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aurnhammer C, Haase M, Muether N et al. Universal real-time PCR for the detection and quantification of adeno-associated virus serotype 2-derived inverted terminal repeat sequences. Hum Gene Ther Methods 2012; 23: 18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi VW, Asokan A, Haberman RA et al. Production of recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors for in vitro and in vivo use. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 2007; 78: 16.25.1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lock M, Alvira MR, Chen SJ et al. Absolute determination of single-stranded and self-complementary adeno-associated viral vector genome titers by droplet digital PCR. Hum Gene Ther Methods 2014; 25: 115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2015. https://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahne F, LeMeur N, Brinkman RR et al. flowCore: a Bioconductor package for high throughput flow cytometry. BMC Bioinformatics 2009; 10: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarkar D, Le Meur N, Gentleman R. Using flowViz to visualize flow cytometry data. Bioinformatics 2008; 24: 878–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finak G, Frelinger J, Jiang W et al. OpenCyto: an open source infrastructure for scalable, robust, reproducible, and automated, end-to-end flow cytometry data analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 2014; 10: e1003806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo K, Hahne F, Brinkman RR et al. flowClust: a Bioconductor package for automated gating of flow cytometry data. BMC Bioinformatics 2009; 10: 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierson T, McArthur J, Siliciano RF. Reservoirs for HIV-1: mechanisms for viral persistence in the presence of antiviral immune responses and antiretroviral therapy. Annu Rev Immunol 2000; 18: 665–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sedlak RH, Liang S, Niyonzima N et al. Digital detection of endonuclease mediated gene disruption in the HIV provirus. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 20064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swiech L, Heidenreich M, Banerjee A et al. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol 2015; 33: 102–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Platt RJ, Chen S, Zhou Y et al. CRISPR-Cas9 knockin mice for genome editing and cancer modeling. Cell 2014; 159: 440–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX et al. In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature 2015; 520: 186–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pham HP, Shaz BH. Update on massive transfusion. Br J Anaesth 2013; 111: i71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chun TW, Carruth L, Finzi D et al. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature 1997; 387: 183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prasad KM, Xu Y, Yang Z et al. Robust cardiomyocyte-specific gene expression following systemic injection of AAV: in vivo gene delivery follows a Poisson distribution. Gene Ther 2011; 18: 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wotherspoon S, Dolnikov A, Symonds G et al. Susceptibility of cell populations to transduction by retroviral vectors. J Virol 2004; 78: 5097–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lo K, Brinkman RR, Gottardo R. Automated gating of flow cytometry data via robust model-based clustering. Cytom A 2008; 73: 321–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aubert M, Boyle NM, Stone D et al. In vitro inactivation of latent HSV by targeted mutagenesis using an HSV-specific homing endonuclease. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2014; 3: e146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber ND, Stone D, Sedlak RH et al. AAV-mediated delivery of zinc finger nucleases targeting hepatitis B virus inhibits active replication. PLoS One 2014; 9: e97579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao K, Li M, Zhong L et al. Empty virions in AAV8 vector preparations reduce transduction efficiency and may cause total viral particle dose-limiting side-effects. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2014; 1: 20139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright JF. AAV empty capsids: for better or for worse? Mol Ther 2014; 22: 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mingozzi F, Anguela XM, Pavani G et al. Overcoming preexisting humoral immunity to AAV using capsid decoys. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5: 194ra92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffman BE, Herzog RW. Covert warfare against the immune system: decoy capsids, stealth genomes, and suppressors. Mol Ther 2013; 21: 1648–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mittereder N, March KL, Trapnell BC. Evaluation of the concentration and bioactivity of adenovirus vectors for gene therapy. J Virol 1996; 70: 7498–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sather BD, Romano Ibarra GS, Sommer K et al. Efficient modification of CCR5 in primary human hematopoietic cells using a megaTAL nuclease and AAV donor template. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7: 307ra156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Exline CM, DeClercq JJ et al. Homology-driven genome editing in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells using ZFN mRNA and AAV6 donors. Nat Biotechnol 2015; 33: 1256–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brantly ML, Chulay JD, Wang L et al. Sustained transgene expression despite T lymphocyte responses in a clinical trial of rAAV1-AAT gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 16363–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flotte TR, Trapnell BC, Humphries M et al. Phase 2 clinical trial of a recombinant adeno-associated viral vector expressing α1-antitrypsin: interim results. Hum Gene Ther 2011; 22: 1239–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mueller C, Chulay JD, Trapnell BC et al. Human Treg responses allow sustained recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated transgene expression. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 5310–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang H, Pierce GF, Ozelo MC et al. Evidence of multiyear factor IX expression by AAV-mediated gene transfer to skeletal muscle in an individual with severe hemophilia B. Mol Ther 2006; 14: 452–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nathwani AC, Rosales C, McIntosh J et al. Long-term safety and efficacy following systemic administration of a self-complementary AAV vector encoding human FIX pseudotyped with serotype 5 and 8 capsid proteins. Mol Ther 2011; 19: 876–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang H. Multiyear therapeutic benefit of AAV serotypes 2, 6, and 8 delivering factor VIII to hemophilia A mice and dogs. Blood 2006; 108: 107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Mascio M, Paik CH, Carrasquillo JA et al. Noninvasive in vivo imaging of CD4 cells in simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV)-infected nonhuman primates. Blood 2009; 114: 328–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.