Highlights

-

•

Isolated spontaneous dissection of the superior mesenteric artery is very rare condition.

-

•

Imaging studies are effective for diagnosis.

-

•

Common treatment strategy consists of three methods as follows; conservative therapy, endovascular treatment, and surgery.

-

•

The etiology and the best treatment have not been established yet.

Abbreviations: SMA, superior mesenteric artery; CT, computed tomography; MDCT, multidetector computed tomography; CTA, computed tomographic angiography; ULP, ulcer-like projection; PGE1, Prostaglandin E1

Keywords: Isolated SMA dissection case reports, Conservative therapy

Abstract

Introduction

Isolated spontaneous dissection of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is rare and a treatment strategy has not been established yet. In this paper, we present our experience with two cases and review the literature.

Presentation of case

Both cases were treated conservatively as they did not show signs of bowel ischemia. They were symptom free with no evidence of disease progression after a median follow-up of 3.5 years.

Discussion

There are three methods for the treatment of isolated SMA dissection; observation with medical therapy, endovascular surgery, and open surgery. Most patients with isolated SMA dissection can be treated with observation alone. Although the indications for surgery are still controversial, patients with bowel ischemia should undergo invasive treatment in the form of either endovascular or open surgery.

Conclusion

We recommend observation with medical therapy as the first choice for isolated SMA dissection. However, long term follow-up is necessary as the extent of the dissection may change over time.

1. Introduction

Spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is a rare condition and potentially fatal. The first case report of isolated SMA dissection was in 1947 by Bauersfeld et al. [1]. Although the number of reported cases has increased with the development of diagnostic imaging techniques, such as multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and CT angiography (CTA), the etiology and natural history have not cleared yet. Moreover, three different treatment strategies for SMA dissection are reported: observation with medical therapy, endovascular therapy, and surgery. There is no consensus as to one optimal therapy.

2. Presentation of case

2.1. Case 1

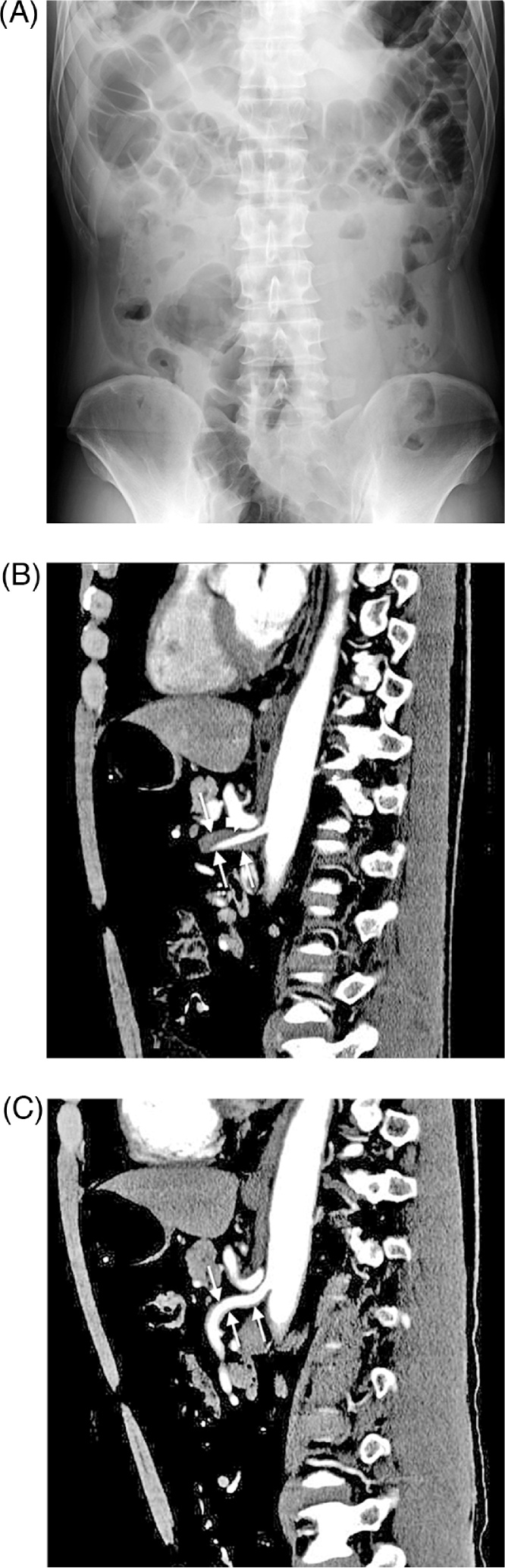

A 58-year-old man presented to the emergency department in a local hospital with severe sudden onset abdominal pain. He had no medical history. Ileus was suspected and he was treated with bowel rest. After four days, he was transferred to our hospital with ongoing abdominal pain. On admission, physical examination revealed mild epigastric tenderness without any signs of peritonitis. Laboratory tests showed hepatic dysfunction with a slightly elevated serum bilirubin as well as leukocytosis. Plain x-ray of the abdomen showed niveau (Fig. 1A). Contrast-enhanced CT showed isolated dissection of the SMA. The dissection began from just after the orifice of the SMA and separated the SMA into two distinct lumens (Fig. 1B). Although the false lumen was completely obstructed and compressed the true lumen, there were no suggestive signs of bowel ischemia, such as bowel thickening, abnormal contrast enhancement, and/or ascites. Therefore, we chose conservative treatment with blood pressure control, fasting, vasodilators, and anticoagulation. His abdominal pain completely disappeared on day 2 and oral intake was resumed without worsening of his symptoms. He was discharged and was symptom-free two years after discharge with no recurrent symptoms or disease progression (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Plain x-ray film of the abdomen showed intestinal gas and niveau (A). Abdominal CT scan showed isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection with true and false lumen (white arrow). The dissection which began from just after the orifice of the SMA and extended to the distal portion. The narrow true lumen was compressed by the thrombosed false lumen (B). After 15 months from the onset, false lumen disappeared (C).

2.2. Case 2

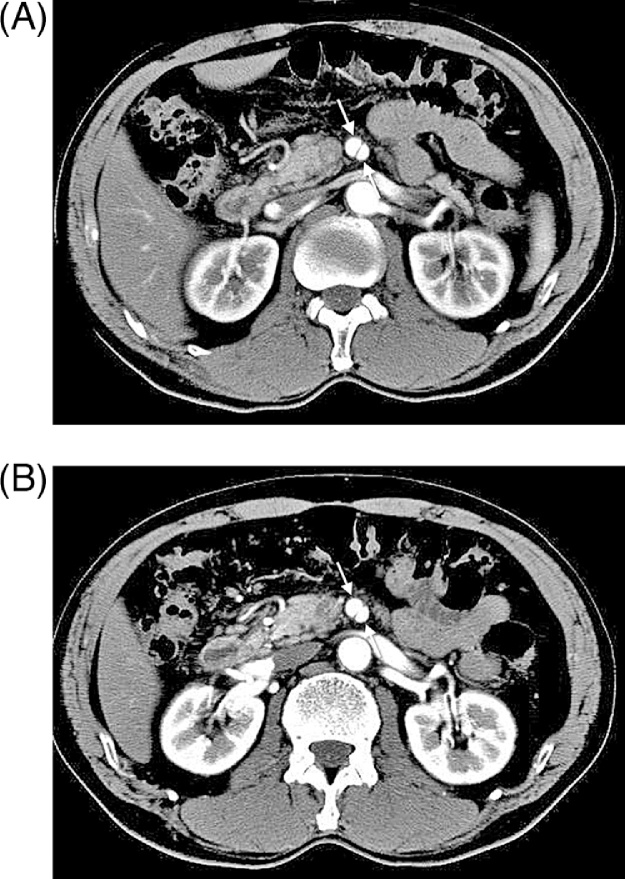

A 67-year-old man presented to the urology department with hematuria. He had no abdominal symptoms. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed an isolated dissection of the SMA and he was referred to our department. There were no signs of bowel ischemia and the dissection was classified as a type I dissection (patent type with an entry and re-entry) by Sakamoto's classification (Fig. 2A). Moreover, there were no signs of the development of an aneurysm. His physical examination and laboratory data were unremarkable. We decided to treat him conservatively with blood pressure control. The patient was symptom-free for five years and there was no progression of dissection on follow-up CT (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Abdominal CT scan showed isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection with true and false lumen, which had patency each other (white arrow) (A). After 18 months from the onset, the dissection did not change without development and/or dilation. In addition, it did not show the formation of aneurysm (B).

3. Discussion

The etiology of isolated SMA dissection has not been elucidated yet, but atherosclerosis, cystic medial necrosis, and fibromuscular dysplasia are thought to be implicated. In addition, untreated hypertension may also have a role [2]. Solis et al. hypothesized that the dissection is caused by stress on the anterior wall of the artery at the inferior edge of the pancreas, where the transition from the fixed to the mobile part of the SMA occurs [3]. In our first case, the dissection began from just after the orifice of the SMA; this is thus not consistent with the hypothesis of Solis et al. On the other hand, the location of the dissection in the second case was in accordance with this hypothesis. Case 1 suggested that the dissection could extend not only distally but also proximally.

The clinical course of this disease is also unclear. Most patients present with acute abdominal pain, which might be due to the dissection itself and/or intestinal ischemia. Other possible symptoms include nausea, vomiting, melena, and abdominal distention [4]. Laboratory tests and abdominal radiography are usually unremarkable. Therefore, patients are often misdiagnosed with other disease processes including gastritis or colitis. As in case 1, intestinal paralysis caused by intestinal ischemia might show niveau on plain x-ray. Interestingly, case 2 was asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally. As the result that isolated SMA dissection can present in a variety of ways.

Accurate diagnosis has become possible as a result of the development of imaging techniques such as MDCT and CTA [2], [5]. Sakamoto et al. have categorized the morphology of isolated SMA dissection into four types based on contrast-enhanced CT images: type I, patent type with an entry and re-entry; type II, “cul-de-sac” type without re-entry; type III, with a thrombosed false lumen with ulcer-like projection (ULP); and type IV, with a completely thrombosed false lumen without ULP [6]. Zerbib et al. added type V accompanied by dissection and stenosis of the SMA and type VI with partial or complete occlusion [7]. Regarding our cases, case 1 was a type I and case 2 was a type IV dissection. However, the classification scheme has not been shown to correlate with clinical outcomes. Recently, abdominal color doppler ultrasound has been effective for diagnosis and for follow-up of isolated SMA dissection [8]. Doppler ultrasound is less invasive but is user dependent; furthermore intestinal gas can obscure visualization of the artery. As a result, we recommend the CT images because of precise, simple, and easy.

Recently, guidelines for isolated SMA dissection have been reported, which included conservative, endovascular, and surgical treatments. However, the best treatment strategy for isolated SMA dissection has not been established yet. Conservative treatment consists of bowel rest and medical treatment including blood pressure control, and anticoagulant, antiplatelet, and thrombolytic therapies [4], [9]. Moreover, it has recently been reported that conservative treatment without anticoagulation or antiplatelet drugs is often sufficient for patients without complications, because isolated SMA dissection generally has a benign course [10], [11]. On the other hand, Karacagi et al. have reported that immediate anticoagulation therapy prevented clot formation in the true lumen in patients with spontaneous dissection of the carotid artery [12]. Nagai et al. insisted that the disease pattern of SMA dissection is similar to that in the internal carotid artery and emphasized that anticoagulation therapy is necessary for SMA dissection [13]. Thus, we treated our patients with blood pressure control, as well as anticoagulant, antiplatelet, and/or thrombolytic therapies. In addition, we used PGE1 as reported by Totsugawa et al. [14]. Overall, conservative treatment is thought to be effective in about 60% of SMA dissections [15]. Physicians who treat SMA dissection should consider the failure of conservative treatment at any moment, which might lead to disease progression and severe complications during follow-up [11]. If the clinical condition worsens during conservative therapy, an endovascular or surgical treatment should be performed [10], [16], [17].

Endovascular treatment for SMA dissection was first reported by Leung et al. in 2000 [15]. It includes thrombolysis, thrombus suction, balloon dilation, stent graft placement, and stenting. The downside of endovascular treatment is that it is difficult to determine whether the intestine is compromised or if there is a risk for arterial rupture [10]. Additionally, endovascular treatment requires specialty training. For these reasons, endovascular treatment has not been established as the initial treatment for SMA dissection.

Many surgical options for isolated SMA dissection have been reported on [10], [16], [17]. Javerliat et al. reported a series of surgical patients with a mean follow-up of 15 months. There were no postoperative deaths [18]. Morris et al. reported good short-term outcomes after surgery (mean 10 months) without any deaths [17]. However, long-term follow-up has not been reported.

4. Conclusion

We recommend that isolated SMA dissections should optimally be treated with observation and medical therapy alone, namely with bowel rest, antihypertensive drugs, anticoagulation and/or antiplatelet drugs, as many cases of isolated SMA dissection will have no complications. However, when intestinal ischemia is suspected on physical examination, endovascular treatment or open surgery including exploratory laparotomy should be considered. Serial examinations not only in the acute phase but also in the chronic and follow-up phases should be performed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Funding

There are no sources of funding.

Ethical approval

The ethics committee of our hospital approved our case report.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and patients' families for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FH was the physician in charge of this patient. FH, ST, and TY made the treatment strategy and performed it. SN and IA gathered data of this condition. FH reviewed the cases, did the literature review, contacted the patient and families, and wrote the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

This is not a research study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Therefore, all authors are responsible for this article.

Contributor Information

Hitoshi Funahashi, Email: funa84@aol.com.

Naoya Shinagawa, Email: n-shinagawa@kkh.miekosei.or.jp.

Takaaki Saitoh, Email: t-saitoh@kkh.miekosei.or.jp.

Yoshihide Takeda, Email: y-takeda@kkh.miekosei.or.jp.

Akihiko Iwai, Email: a-iwai@kkh.miekosei.or.jp.

References

- 1.Bauersfeld S.R. Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta: a presentation of fifteen cases and a review of recent literature. Ann. Intern. Med. 1947;26:73–89. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-26-6-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheldon P.J., Esther J.B., Sheldon E.L., Sparks S.R., Brophy D.P., Oglevie S.B. Spontaneous dissection of the superior mesenteric artery. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2001;24:329–331. doi: 10.1007/s00270-001-2565-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solis M.M., Ranval T.J., McFarland D.R., Eidt J.F. Surgical treatment of superior mesenteric artery compression. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1993;7:457–462. doi: 10.1007/BF02002130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subhas G., Gupta A., Nawalany M., Oppat W.F. Spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection: a case report and literature review with management algorithm. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2009;23:788–798. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki S., Furui S., Kohtake H., Sakamoto T., Yamasaki M., Furukawa A., Murata K., Takei R. Isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery: CT findings in six cases. Abdom. Imaging. 2004;29:153–157. doi: 10.1007/s00261-003-0110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakamoto I., Ogawa Y., Sueyoshi E., Fukui K., Murakami T., Uetani M. Imaging appearaces and management of isolated spontaneous dissection of the superior mesenteric artery. Eur. J. Radiol. 2007;64:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerbib P., Perot C., Lambert M., Seblini M., Pruvot F.R., Chambon J.P. Management of isolated spontaneous dissection of superior mesenteric artery. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2010;395:437–443. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katsura M., Mototake H., Takara H., Matsushima K. Management of spontaneous isolated dissection of superior mesenteric artery: case report and literature review. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2011;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sparks S.R., Vasquez J.C., Bergan J.J., Owens E.L. Failure of nonoperative management of isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2000;14:105–109. doi: 10.1007/s100169910019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho B.S., Lee M.S., Lee M.K., Choj Y.J., Kim C.N., Kang Y.J., Park J.S., Ahn H.Y. Treatment guidelines for isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery based on follow-up CT findings. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. 2011;41:780–785. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jibiki M., Inoue Y., Kudo T. Conservative treatment for isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection. Surg. Today. 2013;43:260–263. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karacagil S., Hardemark H.G., Bergqvist D. Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection. Int. Angiol. 1996;15:291–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai T., Torishima R., Uchida A., Nakashima H., Takahashi K., Okawara H., Oga M., Suzuki K., Miyamoto S., Sato R., Murakami K., Fujioka T. Spontaneous dissection of the superior mesenteric artery in four cases treated with anticoagulation therapy. Intern. Med. 2004;43:473–478. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Totsugawa T., Kuinose M., Ishida A., Tamaki T., Yoshitaka H., Tsushima Y. Spontaneous dissection of the superior mesenteric artery as a rare cause of acute abdomen: report of two cases. Acta Med. Okayama. 2009;63:157–160. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung D.A., Schneider E., Kubik-Huch R., Marincek B., Pfammater T. Acute mesenteric ischemia caused by spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery: treatment by percutaneous stent placement. Eur. Radiol. 2000;10:1916–1919. doi: 10.1007/s003300000520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsura M., Mototake H., Takara H., Matsushima K. Management of spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery: case report and literature review. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2011;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris J.T., Guerriero J., Sage J.G., Mansour M.A. Three isolated superior mesenteric artery dissections: update of previous case reports, diagnostics, and treatment options. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008;47:649–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Javerliat I., Becquemin J.P., d'Audiffret A. Spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2003;25:180–184. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]