Abstract

Doxorubicin (Dox) loaded thermosensitive liposomes (TSLs) have shown promising results for hyperthermia-induced local drug delivery to solid tumors. Typically, the tumor is heated to hyperthermic temperatures (41-42 °C), which induced intravascular drug release from TSLs within the tumor tissue leading to high local drug concentrations (1-step delivery protocol). Next to providing a trigger for drug release, hyperthermia (HT) has been shown to be cytotoxic to tumor tissue, to enhance chemosensitivity and to increase particle extravasation from the vasculature into the tumor interstitial space. The latter can be exploited for a 2-step delivery protocol, where HT is applied prior to i.v. TSL injection to enhance tumor uptake, and after 4 hours waiting time for a second time to induce drug release. In this study, we compare the 1- and 2-step delivery protocols and investigate which factors are of importance for a therapeutic response. In murine B16 melanoma and BFS-1 sarcoma cell lines, HT induced an enhanced Dox uptake in 2D and 3D models, resulting in enhanced chemosensitivity. In vivo, therapeutic efficacy studies were performed for both tumor models, showing a therapeutic response for only the 1-step delivery protocol. SPECT/CT imaging allowed quantification of the liposomal accumulation in both tumor models at physiological temperatures and after a HT treatment. A simple two compartment model was used to derive respective rates for liposomal uptake, washout and retention, showing that the B16 model has a twofold higher liposomal uptake compared to the BFS-1 tumor. HT increases uptake and retention of liposomes in both tumors models by the same factor of 1.66 maintaining the absolute differences between the two models. Histology showed that HT induced apoptosis, blood vessel integrity and interstitial structures are important factors for TSL accumulation in the investigated tumor types. However, modeling data indicated that the intraliposomal Dox fraction did not reach therapeutic relevant concentrations in the tumor tissue in a 2-step delivery protocol due to the leaking of the drug from its liposomal carrier providing an explanation for the observed lack of efficacy.

Keywords: Drug delivery, hyperthermia, thermosensitive liposome, intravascular drug release, particle accumulation.

Introduction

Classical chemotherapy for treatment of solid tumors typically employs cytotoxic drugs with low molecular weight that have sizes below 1 nm. The latter allows the drugs to efficiently extravasate upon injection from the vascular compartment into the tumor tissue in order to reach their targets. However, as extravasation is not restricted to the tumor tissue, toxicity imposed on healthy tissues is limiting the therapeutic window. One approach to limit off-target toxicity is the encapsulation of cytotoxic drugs into nanoparticles, such as liposomes with sizes in the range of 50-200 nm, which reduces side effects observed for free drugs. In contrast to healthy tissues, tumors exhibit a poorly organized vascular system 1, 2 with endothelial gaps 3, 4 that allow extravasation and accumulation of nanoparticles up to several hundred nanometers 1, 5. In addition, as tumors often lack a functional lymphatic system, which impedes efficient clearance of nanoparticles, substantial retention of long circulating nanoparticles is observed 6, 7. This enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect was first described for macromolecules by Matsumura and Maeda 8 and is a prerequisite for liposomal drug targeting. Today, several lipomosal drug formulations are clinically approved, mostly due to their improved toxicity profile 7. One example is Doxil®, a long circulation liposomal formulation of Doxorubicin (Dox) 9, 10. While liposomal encapsulation reduces off-site toxicity, it unfortunately reduces bioavailabity of the parent drug. Drug release from the liposomal carrier is slow as it is based on passive diffusion of the drug across the liposomal lipid bilayer, which strongly reduces peak concentrations 11. An alternative approach is heat-triggered drug delivery using a drug that is encapsulated in the aqueous core of a temperature sensitive liposome (TSL), as first proposed by Yatvin and Weinstein 12. A TSL retains the drug at body temperature, but rapidly release their payload at mild hyperthermic temperatures (40-43 °C). Heating the targeted tissue to these temperatures, for example using radiofrequency or high intensity focused ultrasound, leads to rapid intravascular release with subsequent substantial drug deposition in the tumor, which is investigated in numerous preclinical 13-17, yet also clinical studies 18, 19.

Next to providing a trigger for drug release, hyperthermia (HT) exposure can induce multiple other changes on cellular as well as tissue level 20, 21. HT can cause direct cytotoxicity in vitro 22 and in vivo, which depends on the absolute temperature and exposure time, but also on the type of cell or tissue 23, 24. Secondly, HT can increase chemosensitivity 25, 26 due to a synergistic effect between HT- and drug-induced cytotoxicity or due to an increased drug uptake as HT enhances cell membrane permeability 27, 28. On tissue level, preclinical studies have shown that HT increased liposomal uptake in tumors 29-33. However, clinical trials using Doxil® in combination with HT showed variable therapeutic outcomes, highlighting the clinical need for liposomal formulations that could more effectively release the drug 34, 35. The latter inspired the design a 2-step drug delivery scheme, where first HT is applied to enhance the EPR effect followed by injection of TSLs. After accumulation of TSLs in the tumor, drug release is triggered with a second application of HT to ensure bioavailability of the drug.

In a previous study, Li et al. performed a comparative study with Dox loaded TSL using the aforementioned 2-step drug delivery scheme versus a 1-step intravascular HT-drug delivery scheme in a murine BLM melanoma model 36. The conclusion of that study was that a 1-step treatment was more efficacious in treating a solid tumor than the 2-step approach. Here we provide a follow-up study, investigating 1-step and 2-step HT TSL based treatments in terms of in vitro cytotoxicity, drug uptake by cells, therapeutic efficacy and quantitative TSL uptake by B16 melanoma and BFS-1 sarcoma tumors. Furthermore, extensive ex vivo investigation provide data giving more insights into microenvironmental factors that could play a role in TSL accumulation for B16 and BFS-1 tumors and the influence of HT on these factors.

Materials & Methods

Materials

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(amino(polyethylene glycol)-2000) (DSPE-PEG2000) were purchased from Lipoid (Ludwigshafen, Germany). DSPE-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Doxorubicin-hydrochloride solution (2 mg/ml) was ordered from Accord Healthcare. 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), (NH4)2SO4, DMEM culture medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), sulforhodamine B (SRB), poly(2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate; HEMA), 2-Amino-2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol (Tris), NaCl, glycerol, Mayer's hematoxylin, eosin Y, Martius yellow, crystal scarlet and methyl blue were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol (NP40) was purchased from ICN Biomedicals (Irvine, CA). Penicillin-streptomycin (Pen-Strep) solution was from Lonza (Breda, Netherlands). PD-10 desalting columns were bought from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Buckinghamshire, UK). Entallan and rabbit-anti mouse Collagen IV antibody were from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). CD31 antibody (rat anti-mouse) was bought from Abcam (Cambridge, UK) and AlexaFluor 594 (goat anti-rat) and AlexaFluor 488 (goat anti-rabbit) from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Matrigel was acquired from BD (San Jose, CA). Cryo compound was from Klinipath (Duiven, Netherlands). Fluoromount-G was provided by Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL). Cell death detection kit was obtained from Roche (Woerden, Netherlands). Weigert's hematoxylin was purchased from Boom Chemicals (Meppel, Netherlands).

Liposome preparation

DPPC:DSPC:DSPE-PEG2000 at a molar ratio of 70:25:5 were dissolved in 9:1 (vol:vol) chloroform/methanol. Solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator and the resulting lipid film was flushed under a stream of nitrogen. The lipid film was hydrated with a 250 mM solution of (NH4)2SO4 buffer pH 5.5 and extruded five times through 200 nm, 100 nm, 80 nm and 50 nm polycarbonate membrane filters. A pH gradient was established using a PD-10 column and eluting the liposomes with a pH 7.4 HEPES buffered saline (10 mM HEPES, 135 mM NaCl). Phosphate concentration was determined by ammonium molybdate assay 37. Dox was loaded into the liposomes by mixing Dox and lipid at a ratio of 0.15:1 (mol:mol) and incubating it for 1 h at 39°C in a thermoshaker. Liposomes were concentrated by ultracentrifugation (193000 g, 2 h, 4°C) and resuspended in 10 mM HEPES buffered saline pH 7.4 yielding the final formulation of Dox-loaded TSLs (TSLDox).

Radiolabeled liposome preparation

For radiolabeled TSLs (111In-TSL), 0.1 mol% DSPE-DTPA was added to the formulation described above and produced in a similar fashion as the regular TSLs, with the exception that the liposomes were not loaded with Dox. 1 µmol TSLs was incubated with 30 MBq 111In for 15 min at room temperature after the pH was set at 5.0 with 2.5 M sodium acetate. After incubation, labeling efficiency was determined by ITLC-SG (Varian Inc.) and the final volume was adjusted to 200 µL with HEPES buffered saline (10 mM HEPES, 135 mM NaCl, pH 7.4).

Cellular toxicity assay

B16 or BFS-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to grow till 50% confluency in DMEM medium enriched with 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep. The medium was removed and fresh medium with a desired amount of free Dox or TSLDox was brought onto the cells and incubated according to Scheme 1. NT: incubation with Dox for 1 h at 37°C; HT42: incubation with Dox for 1 h at 42°C; HT41-NT: Preheating cells 1 h at 41°C, 4 h recovery at 37°C and a 1 h incubation with Dox at 37°C; HT41-HT42: Preheating cells for 1 h at 41°C, 4 h recovery at 37°C and a 1 h incubation Dox at 42°C. For a TSLDox treatments on cells, 10 µM Dox was used. To apply HT, plates were put into a water bath set at the required temperature. After incubation, the Dox containing medium was removed and cells were given fresh medium for 24 h or 48 h incubation at 37°C. Cells were fixed using 10% (w:v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA). After fixation, the plates were washed with water and 0.5% SRB solution was added to stain the fixed cells for 20 min. When staining was completed, cells were washed with 1% acetic acid and left to dry. 10 mM Tris was added to resuspend the SRB and absorbance was measured at 590 nm by spectrophotometry (Wallac Victor 2 Counter).

Scheme 1.

Overview of different in vitro Dox uptake treatments. Dox exposure took place at 37°C (NT) or 42°C (HT42). In two additional groups, cells were preheated for 1 h at 41 °C (HT41) with a 4 h recovery at 37°C before Dox uptake under NT or HT42 conditions (HT41-NT and HT41-HT42, respectively)

Cellular Doxorubicin uptake in 2D and 3D models

B16 or BFS-1 cells were seeded into 75 cm2 flasks and grown under similar conditions as mentioned above until 80% confluency was reached. The cells were subjected to 40 µM Dox under four different treatment conditions as stated in Scheme 1. Exposing cells to elevated temperatures was done by submerging the 75 cm2 culture flask into a water bath. After incubation, the cells were washed with ice cold PBS, scraped from the flask and centrifuged at 200 g at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in 150 µL lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% NP40, 10% glycerol, pH 7.4), followed by 30 min incubation on ice and centrifugation at 14000 g. The pellets were resuspended and homogenized in 500 µL PBS by brief probe sonication and Dox concentration was measured by fluorometry at 485 nm excitation and 580 nm emission (Wallac Victor 2 Counter). Tumor spheroids were made according to a previously described method 38. In short, conical shaped 96-well plates were coated with poly-HEMA and 1 x 105 cells which were centrifuged at 1000 x g for 10 min in the presence of 2.5% Matrigel and incubated overnight at 37°C. After incubation, spheroids were handpicked and exposed to identical treatments as in the 2D model in a thermoshaker (no shaking). After incubation, the spheroids were washed in PBS, embedded into Fluoromount-G and imaged by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510 Meta; Oberkochen, Germany). A 5 µm Z-stack was made over the surface of the spheroid to determine total Dox fluorescence. For each optical slice, the amount of saturated Dox fluorescence pixels were counted. The sum of saturated pixels of all tumor slices was used as an indicator for Dox uptake. For cryo-sectioning, spheroids were embedded into Cryo Compound and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. 10 µm slices were made using a Cryostat (Leica CM1850 UV; Wetzlar, Germany), and afterwards embedded into Fluoromount-G and imaged using fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert 100M; Hamamatsu Photonics C4742-98 camera controller).

B16 and BFS-1 tumor generation

Murine B16 melanoma or BFS-1 sarcoma cells (1 x 106) were subcutaneously injected into the flank of C57BL6 mice (Harlan) to grow bulk tumors. After reaching volumes of approx. 700 mm3, animals were sacrificed and tumor pieces were transplanted to the animals of the therapeutic studies. All animal experiments were approved by the Erasmus MC animal research committee, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Therapeutic efficacy studies in a B16 and BFS-1 model

1 mm3 B16 or BFS-1 tumor pieces were transplanted subcutaneously onto the hind limb of C57BL6 mice and allowed to grow to 200 mm3 after which treatments were initiated as shown in Scheme 2. NT: 1-step with 100 µL i.v. PBS injection and 1 h anesthesia at body temperature; HT42: 1-step with 100 µL i.v. PBS injection and 1 h anesthesia with heated tumor at 42 °C; TSLDox NT: 1-step with 100 µL 5 mg/kg TSLDox i.v. injection and 1 h anesthesia at body temperature; TSLDox HT42: 1-step with 100 µL 5 mg/kg TSLDox i.v. injection and 1 h anesthesia with heated tumor at 42 °C; HT41-HT42: 2-step with 1 h preheating tumor at 41 °C under anesthesia, 100 µL i.v. PBS injection, 4 h waiting period and 1 h anesthesia with heated tumor at 42 °C; TSLDox NT-HT42: 2-step with 1 h anesthesia at body temperature, 100 µL 5 mg/kg TSLDox i.v. injection, 4 h waiting period and 1 h anesthesia with heated tumor at 42 °C; TSLDox HT41-HT42: 2-step with 1 h preheating tumor at 41°C under anesthesia, 100 µL 5 mg/kg TSLDox i.v. injection, 4 h waiting period and 1 h anesthesia with heated tumor at 42 °C. In the 1-step treatment protocol, the tumor was submerged into a 42.5 °C water bath for heating to 42 °C for 10 min, followed by an i.v. injection of TSL (5 mg/kg Dox) and further heating for another hour. The 2-step treatment procedure included heating of the tumor to 41 °C for one hour and an i.v. injection of TSL (5 mg/kg Dox) 10 min after heating. Afterwards, the animal was allowed to rest for 4 h, followed by a second HT treatment for 1 h at 42 °C. In control groups normothermic (NT; 35 °C) conditions were used, where the animal was put under anesthesia for 1 h and kept at 35 °C on a 37 °C heating plate while covering the animal with tin foil. During both HT and NT experiments, the tumor bearing limb, with exception of the tumor itself, was coated in vaseline to prevent possible skin burns. Body temperatures of the mice were measured using a rectal probe.

Scheme 2.

Overview of 1-step and 2-step treatments in vivo. For 1-step, i.v. TSLDox administration was conducted at body temperature (NT) or when the tumor was brought to 42 °C (HT42). 2-step treatments were composed of keeping the mouse under anesthesia at body temperature for 1 h (NT-HT42) or preheating the tumor at 41 °C for 1 h (HT41-HT42), prior to TSLDox injection, 4h rest and a second tumor heating at 42 °C.

SPECT/CT imaging of TSL accumulation in a B16 and BFS-1 model

1 x 106 cells were subcutaneously injected on the hind limb of C57BL6 mice and tumors were allowed to grow to volumes of 200 mm3. Tumors were either heated for one hour at 41 °C prior to injection or kept at 35 °C in a similar fashion as for the therapeutic study. 111In-TSL were i.v. injected (200 µL per mouse with an average activity of 33 ± 2 MBq 111In) and scans were made 4 h, 8 h, 24 h and 48 h after injection. Scans were acquired using the nanoSPECT/CT (Mediso Medical Imaging Systems) with the following settings for the SPECT scans: 20 projections, 60 seconds/projection, and a quality factor of 0.8. APT1 apertures were used with 1.4 mm diameter pinholes (FOV 24 + 16 mm). CT scans were acquired with 240 projections, 45 kVp tube voltage and 500 ms exposure. Data analysis was performed using InVivoScope/VivoQuant software (inviCRO, Boston, MA), where three-dimensional regions of interest were drawn over the tumor to calculate uptake of 111In-TSL at the selected time points. After the last scan, the animals were sacrificed and tumors and organs were harvested, weighed and radioactivity was determined using a γ-counter to calculate percentage injected dose per gram (%ID/g). All data were corrected for radioactive decay.

Pharmacokinetic modelling

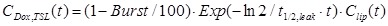

The blood kinetics and pharmacokinetic parameters of the TSLDox formulation were determined in an earlier study (Figure S1) 39. Results from that study showed that the blood half-life of liposomal carrier Clip(t) can be described with a mono-exponential function:

|

(eq.1) |

with Clip(0)=100%ID at time point of injection and t1/2,TSL= 5.6 ± 0.4 h being the circulation half-life of the liposomes. Upon injection, a fraction of Dox is instantaneous released (Burst = 8 ± 3 %) followed by a slow leakage of Dox from the liposomal carrier with a half-life of t1/2,leak = 2.7 ± 0.3 h. The concentration of intraliposomal dox CDox,TSL(t) can be described with the following equation:

|

(eq.2) |

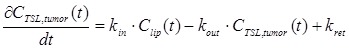

The concentration of (radiolabeled) liposomes in the tumor, CTSL,tumor(t), can be described with a simple two compartment model:

|

(eq.3) |

where kin, kout and kret describe the rates of uptake, washout and retention of TSL in the tumor compartment.

Concentration of intraliposomal Dox within the tumor is subsequently numerically calculated assuming the same burst and leakage of Dox from the liposomal carrier as found for TSLDox in the blood compartment.

Numerical integration of Eq. 3 and fitting of the SPECT data was performed using Mathematica® (version 10.2, Wolfram Research).

Histology

After the SPECT/CT experiments, the excised tumors were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. 5 µm slices were cut and tumors were stained for vessels with an anti-CD31 antibody and AlexaFluor 594 or collagen with anti-collagen IV antibody and AlexaFluor 488. The TUNEL staining was performed with a cell death detection kit. The CD31 and TUNEL stains were quantified using ImageJ (version 1.48) software and by setting a manual threshold. A second set of frozen slices was stained with Maier's hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) or by Weigert's hematoxylin, Martius yellow, crystal scarlet and methyl blue (MSB), followed by mounting in Entallan. The slices were imaged for fluorescence by confocal microscopy (CD31, collagen IV & TUNEL) or bright field microscopy (Leica DM 4000B) for H&E and MSB stained sections.

Statistics

All statistical tests were carried out using Graphpad Prism 5 software. All figures were subjected to unpaired two tailed t-test or one-way ANOVA Bonferroni test with significant difference at p < 0.05.

Results

Preparation of TSLDox

Loading of TSL with the formulation DPPC:DSPC:DSPE-PEG2000 at a molar ratio of 70:25:5 with Dox was achieved with 100% efficacy. Dynamic light scattering of the resulting TSLDox indicated an average hydrodynamic diameter of 83 ± 3 nm and a zeta-potential of -7.9 ± 0.9 mV. Stability at 37 °C and release kinetics at 42 °C were tested in culture medium (10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep) and were found to be similar to results obtained with 100% FBS as described in our previous work (Figure S2) 39.

Cytotoxic assays on B16 melanoma and BFS-1 sarcoma cells

In an in vitro study, murine B16 melanoma and BFS-1 sarcoma cells were exposed to various Dox concentrations for 1 h under the conditions depicted in Scheme 1. Both cell lines showed an increased sensitivity to Dox when the drug exposure was performed at hyperthermic temperatures (Figure 1). For B16 (Figure 1A, B) and BFS-1 (Figure 1C, D), the Dox sensitivity increased 8-fold. Additional pre-heating (HT41-HT42) did not result in a further increase in Dox sensitivity for B16. However, the 18-fold increase for BFS-1 was significantly higher than the single HT treatment. In this case direct HT-induced cytotoxicity could have played a predominant role (Figure S3). B16 and BFS-1 cells were furthermore tested for survival after incubation with TSL (empty), 10 µM TSLDox or 10 µM free Dox under normothermic (NT; 37 °C) and HT42 conditions for 1 h. After the treatment, the cells were kept in culture medium for 24 h or 48 h. At 37 °C, TSLDox induced little toxicity to the cells, while at 42 °C the release of Dox was sufficient to cause high cell death (Figure 2). The TSL by itself had no inhibitory effect on cell growth, while HT did show some direct cytotoxicity, which was only significant for B16 24 h after incubation with 72 ± 11% viable cells compared to the NT group (Figure 2A). The addition of 10 µM TSLDox to a 1 h incubation with HT42 resulted in an immediate cytotoxic effect 24 h after the incubation (Figure 2A) with 25 ± 6% for B16 and 57 ± 7% cell survival for BFS-1. This cytotoxic effect became even more apparent 48 h after incubation, showing an almost complete cell death for both cell types (Figure 2B). The TSLDox HT42 group showed similar results as where 10 µM free Dox was used (Dox HT42), suggesting a total Dox release from TSLDox in these experimental conditions. A cytotoxicity assay using a 2-step heating protocol was not performed, as the main cytotoxic effect was caused by the increased uptake of free or released Dox during HT42.

Figure 1.

Dox cytotoxicity assay and IC50 values for B16 (A, B) and BFS-1 cells (C, D) 48h after treatment by different hyperthermia protocols. n = 3 for each data set. Curves were fit by non-linear regression and statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA Bonferroni test. The significance scores of all treatments versus NT groups are indicated with asterisks. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.005.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity assay on B16 and BFS-1 cells 24 h (A) and 48 h (B) after a 1 h incubation with 10 µM TSLDox or free Dox under NT (37 °C) or HT42 (42 °C) conditions. n = 3 for each data set. Statistical analysis was carried out using one way ANOVA Bonferroni test comparing the treatment groups with the NT group separately at 24h and 48h. The significance scores of all treatments versus NT groups are indicated with asterisks. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.005.

In vitro Doxorubicin uptake in 2D and 3D models

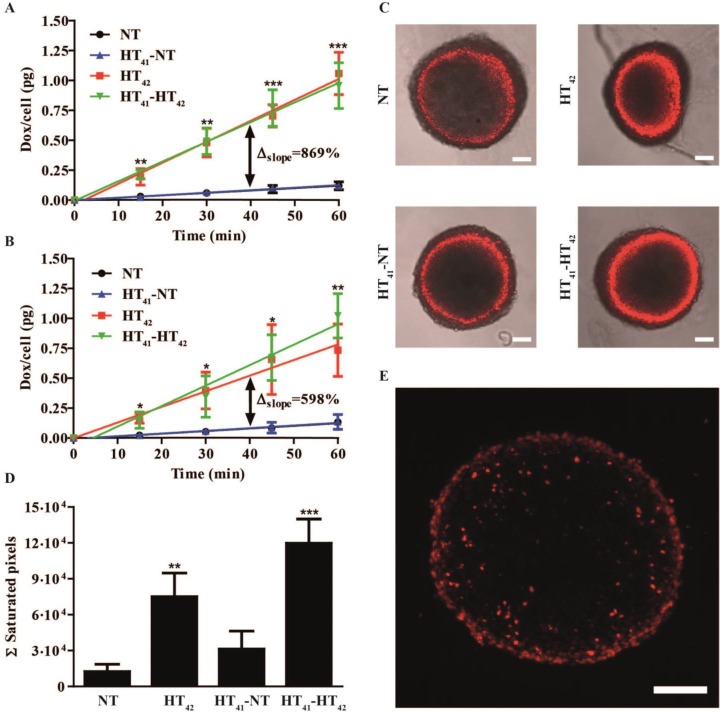

Next, the effect of HT on Dox uptake was studied in B16 and BFS-1 cells. Both cell lines exhibited a linear uptake of Dox over time at body temperature (Figure 3A,B). Incubation of both cell lines with Dox at HT42 significantly increased Dox uptake 9-fold for B16 (Figure 3A) and 6-fold for BFS-1 cells (Figure 3B). Groups were added where the cells were preheated at 41 °C for 1 h followed by 4 h at 37 °C to mimic a 2-step approach therapy. Preheating of the cells before incubation with Dox at NT (HT41-NT) or HT42 (HT41-HT42) conditions did not result in a significant difference compared to Dox uptake without preheating. Next, we used multicellular spheroids of BFS-1 cells to determine the Dox uptake as well as spatial distribution under the different temperature protocols in a 3D model. After performing similar incubation protocols as described before, the BFS-1 spheroids showed a similar pattern in Dox uptake than BFS-1 cells in the 2D standard culture conditions (Figure 3C, Video S1). When the Dox fluorescence intensity was quantified (Figure 3D), HT42 and HT41-HT42 presented significantly more Dox positive areas than NT spheroids with a 6-fold and 10-fold increase in the summation of saturated Dox fluorescence pixels, respectively. HT41-NT treatment did not result in a significantly enhanced uptake. Dox did not penetrate farther than the first few cell layers into the spheroid, despite the heating protocol used (Figure 3E). B16 cells did not form spheroids and could therefore not be studied in the 3D Dox uptake model.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional Dox uptake in B16 (A) and BFS-1 (B) cell cultures and BFS-1 spheroids (C-E). Cells or spheroids were exposed to 40 µM Dox for 1 h at 37 °C (NT), 42 °C (HT42), or preheated at 41 °C followed by 4 h at 37 °C before a 1 h exposure to 40 µM Dox at NT (HT41-NT) or HT42 (HT41-HT42). Optical slices of 5 µm made by confocal microscopy of the spheroid (C) were summed up to determine the Ʃ saturated pixels (red) per spheroid (D; Video S1). Cryosections of 10 µm (E) of the BFS-1 spheroids show spatial distribution of Dox fluorescence (red). All data sets are composed of an n = 3 experiment and compared by one way ANOVA Bonferroni test, * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.005. Asterisks show significance compared to NT groups. Scale bars represent 100 µm.

1-step & 2-step therapeutic study

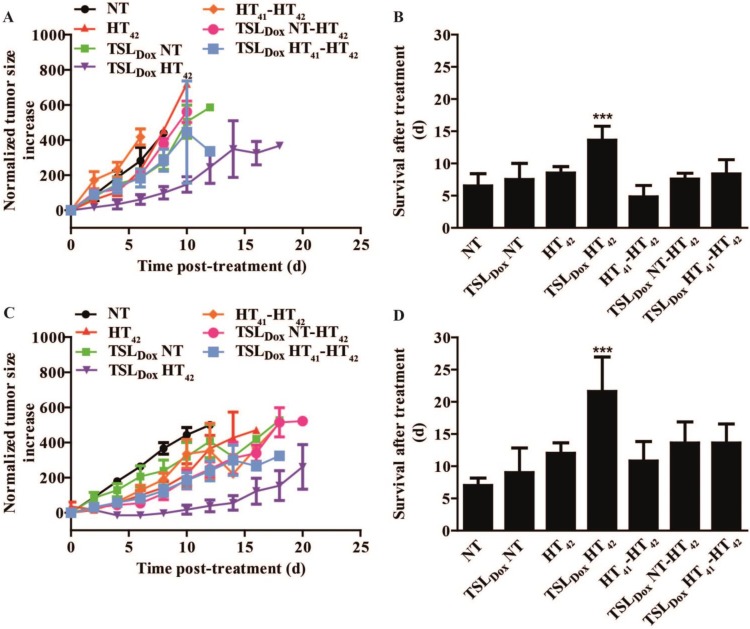

A therapeutic study with B16 (Figure 4A, B) and BFS-1 (Figure 4C, D) tumors were subjected to 1-step or 2-step therapies (Scheme 2). We chose 41 °C as preheating temperature since it has been shown that an intratumoral increase of TSLDox accumulation can be established 31 without risking significant vascular damage 40. In both B16 and BFS-1 tumors, TSLDox with HT42 significantly outperformed all other treatments with an average improvement of survival of 7.1 ± 1.4 days for B16 and 14.6 ± 2.8 days for BFS-1 when compared to the NT group. The body temperature differed significantly between NT and HT42 treated mice (Figure S4). Nevertheless, it remained at a physiological level with 35.0 ± 0.4 °C and 36.9 ± 1.1 °C, respectively.

Figure 4.

Therapeutic efficacy study in C57BL6 mice with s.c. B16 or BFS-1 tumors. After treatment, results for B16 tumors were plotted for growth (A) and survival (B). Survival (B) was based on a size cutoff at 300% tumor size increase. Error bars in growth curve (A) represent SEM and one way ANOVA Bonferroni test was used to determine differences of survival in B (* = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.005). Asterisks above bars show significance versus NT. BFS-1 is presented similarly in C and D. n = 4 for NT, TSLDox NT and HT42 groups; n = 5 for all other groups.

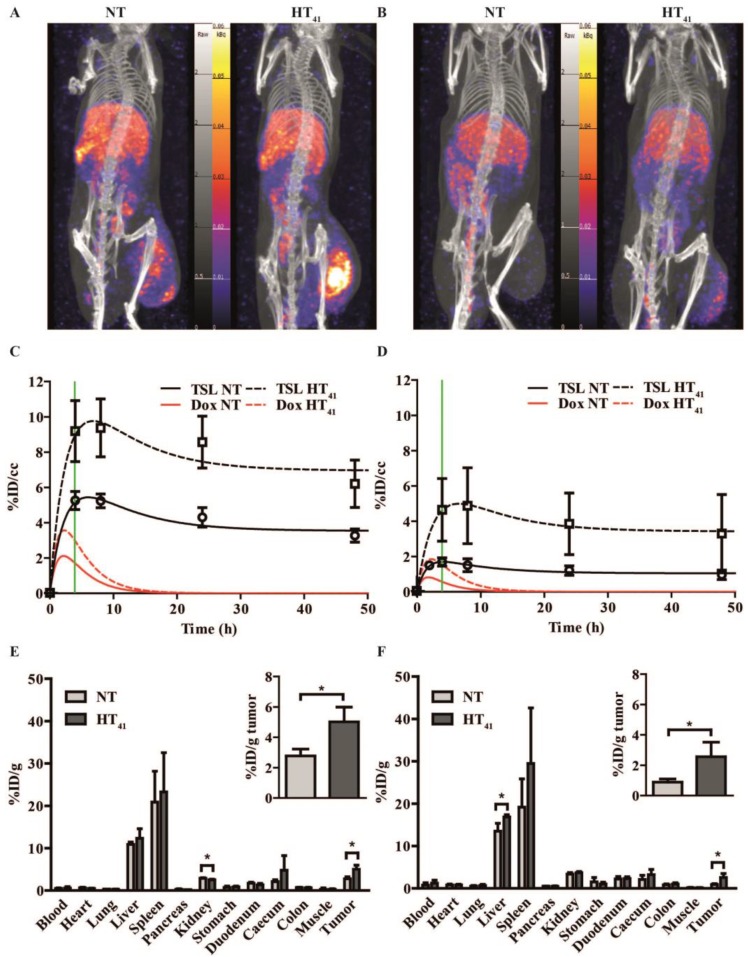

Quantitative SPECT/CT imaging of TSL accumulation in solid tumors

A SPECT/CT study with 111In-TSL (labeling efficiency > 99%) was carried out to visualize the particle uptake in B16 and BFS-1 tumor bearing mice, comparing NT conditions versus tumor preheating for 1 h at 41°C prior to injection (HT41). SPECT imaging over time showed that the majority of the injected 111In-TSL were cleared by liver and spleen (Figure 5A, B) with tumor uptake over time. For all tumors, a maximum uptake was observed approx. 4 h post injection followed by a slight reduction over time leveling off at 48 h post injection. Under NT conditions, plateau values of 3.2 ± 0.5 and 1 ± 0.3 %ID/cc were reached for B16 and BFS1 tumors respectively. Applying HT41 before injection increased uptake in both tumors, leading to higher maximum as well as plateau concentrations (B16: 6.2 ± 1.5 %ID/cc, BFS1: 3.3 ± 2.8 %ID/cc at 48 h p.i.) (Figure 5A-D). Biodistribution studies at t = 48 h p.i. were consistent with data derived from SPECT showing an uptake of 111In-TSL in B16 tumors 2.8 ± 0.5 %ID/g compared to a considerable lower uptake of 0.9 ± 0.2 %ID/g in BFS-1 tumors for NT experiments (Figure 5E,F). Applying HT41 before injection resulted in a significantly increased 111In-TSL accumulation measured after 48 h in B16 tumors (5.0 ± 1.0 %ID/g; Figure 5C, E) and BFS-1 tumors (2.6 ± 1.0 %ID/g; Figure 5D, F).

Figure 5.

SPECT-CT study on 111In-TSL distribution in B16 (A, C, E) and BFS-1 (B, D, F) tumor bearing mice. After i.v. administration, scans were made at 4 h, 8 h, 24 h and 48 h for all groups. B16 (A, C) and BFS-1 (B,D) tumors showed 111In-TSL accumulation after i.v. administration at NT, which could be significantly enhanced (unpaired two-tailed t-test; p < 0.05) by pre-heating the tumor for 1 h at 41 °C prior to 111In-TSL administration (HT41). The green line shows the 4 h time point where a second HT treatment would have taken place in case of a 2-step therapy. Biodistribution of 111In-TSL was done by γ-counting on excised organs and tumors (E, F) 48h hours after injection. Every group consisted of three animals (n = 3).

SPECT data were used to fit the liposomal tumor uptake according to a simple two compartment model, deriving the rates for uptake, washout and retention, kin, kout, kret, in the two different tumors under NT and HT41 conditions (Table 1). Taking the earlier determined pharmacokinetic properties of the here used TSLDox formulation into account (Figure S1), the model also allowed to calculate the concentration of intraliposomal Dox present in the tumors as a function of time (Figure 5C,D). Maximum concentrations of intraliposomal Dox were reached approx. 2 hours p.i.. In contrast to the liposomal concentrations, intraliposomal Dox concentrations decreased to zero 15-20 hours p.i. due to the leakage from the liposomal carrier.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters describing the tumor TSL uptake and retention in B16 and BFS-1 tumors.

| Tumor | Condition | kin / (1/h) | kout / (1/h) | kret / (1/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16 | NT | 0.0157 ± 0.004 | 0.39 ± 0.16 | 1.4 ± 0.63 |

| HT41 | 0.0233 ± 0.007 | 0.36 ± 0.22 | 2.5 ± 1.64 | |

| BFS-1 | NT | 0.0074 ± 0.003 | 0.69 ± 0.34 | 0.7 ± 0.38 |

| HT41 | 0.0127 ± 0.001 | 0.36 ± 0.07 | 1.2 ± 0.24 |

The uptake as well as the retention rate of liposomes in B16 tumors was ca. 2 times higher compared to BFS-1 tumors, while washout was comparable for both tumors. Notably, HT41 induced in both tumors a comparable effect with increasing the kin, and kret by a factor of ca. 1.66 ± 0.13 leading to a more rapid and higher uptake of liposomes and consequently a high Dox peak concentration.

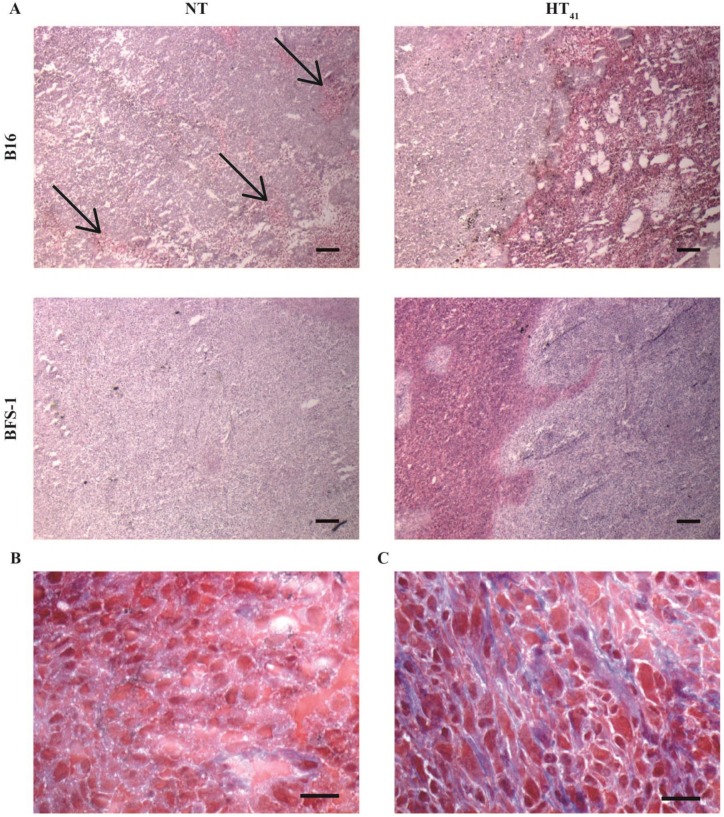

Histology

After the SPECT-CT study, the tumors were used for H&E, MSB, TUNEL, CD31 and collagen IV staining (Figure 6 & 7). H&E staining indicated that B16 tumors have less strong cellular interactions as can be seen by the gaps in the tissue (Figure 6A), whereas BFS-1 has a much more compact morphology. Furthermore, the H&E suggests that the B16 tumors are more apoptotic (Figure 6A, arrows). Yet after HT41, apoptotic areas could be seen in both tumor types. MSB staining showed that B16 tumors have a very low presence of extracellular fibers (Figure 6B), whereas BFS-1 showed a more mature extracellular matrix (Figure 6C). Quantitative TUNEL staining (Figure 7A) showed high apoptosis of 14.4 ± 10.0% for B16 when compared to BFS-1 with 0.4 ± 0.1%. HT41 caused an increase of apoptosis, showing 24.5 ± 13.2% for B16 and 1.2 ± 0.4% for BFS-1, which was a significant increase for the latter. The vessel staining using CD31 indicated a comparable mean vessel density for both tumor models (Figure 7B). The quantitative collagen IV staining confirmed the result of the MSB staining with 3.6 ± 0.3% for B16 and 14.8 ± 1.2% mean density for BFS-1 (Figure 7C). The B16 vessels were relatively large with collagen almost solely associated with the vessels (Figure 7D), whereas BFS-1 vessels were smaller and the interstitium consisted of more extracellular collagen matrix (Figure 7E).

Figure 6.

5 µm H&E stained sections of B16 and BFS-1 tumors 48 h after NT or HT41 (A). Black arrows indicate apoptotic areas. MSB stained B16 (B) and BFS-1 (C) with collagen stained in blue. Scale bars represent 200 µm in A and 20 µm in B and C.

Figure 7.

Quantification of cryo-section staining with TUNEL (A), CD31 (B) and collagen IV (C) was analyzed by unpaired two tailed t-test (* = p < 0.05). B16 (D) and BFS-1 (E) blood vessels colored red for CD31. Collagen IV stained in green. Scale bar shows 50 µm. n = 3 for all groups.

Discussion

In the field of nanomedicine, substantial research has been performed throughout the last decades on HT-triggered drug release from TSLs for treatment of solid tumors. In this context, mainly 1-step intravascular drug delivery schemes were employed, where tumors are heated to hyperthermic temperatures and drug loaded TSL are injected at the start of the HT treatment. In a previous study conducted by Li et al 36, a 2-step treatment scheme was investigated as a possible alternative in a BLM melanoma xenograft, where first HT41 is applied to enhance vascular permeability, then a TSLDox formulation was injected that subsequently accumulated in the tumor, followed by a second HT42 step to release the drug from its carrier in order to ensure bioavailability. The aforementioned study showed in contrast to the 1-step therapy, that the 2-step approach was not effective in causing a therapeutic response. In our experimental design we chose for a B16 melanoma and BFS-1 sarcoma cell line because tumors from these cell lines have been previously reported to show high and low EPR-mediated uptake of TSL, respectively 31. We tested how these tumors respond to a 1-step versus 2-step therapy, expanded the knowledge on how the tumor models responded to single versus multiple HT treatments in combination with local chemotherapy and provide extensive information on what factors can cause the differences in TSL accumulation between these tumors and which of these factors could be influenced by HT to increase TSL accumulation.

B16 and BFS-1 cells showed a significant increase in Dox sensitivity when the drug exposure happened during HT42. The reduced IC50 with HT correlated with the increase Dox uptake by the cells discussed hereafter. Previously published data on this correlation showed that the outcome of these experiments depend on cell type and specific experimental conditions, e.g. exact temperature and duration of HT exposure 27, 41-43. Testing TSLDox on these cells showed that at 37 °C the cytotoxic effect is minimal, whereas at 42 °C, the TSLDox released all drug and therefore cytotoxicity was comparable to free Dox. The small cytotoxic effect at 37°C could be caused by cellular uptake of TSLDox or by Dox leaking from the liposomes into culture medium (Figure S2). Next, we investigated the presence of a synergistic effect of Dox and HT for different heating schemes in a 2D and 3D cellular model. In a 2D model, it was shown that HT42 induces a faster cellular uptake of Dox leading to a 6-9 times higher rate of uptake in B16 and BFS-1 cells than at 37 °C. Preheating the cells for 1 h with HT41 followed by incubation for 4 h at 37 °C before adding Dox did not show any improvement of Dox uptake, indicating that HT-induced effects at 41 °C were reversible in nature and could only improve drug uptake during the heating and not thereafter. As the Dox uptake is caused by passive diffusion across the cell membrane, increase of cellular membrane fluidity and permeability during HT is the most likely explanation, since these effects are temporal in nature and fully reversible 27, 28. Other studies have shown that preheating to slightly higher temperatures of 43-45.5 °C lead to a reduced Dox uptake most likely due to a more permanent and irreversible temperature of thermal dose induced damage 41, 44. However, HT41 used for preheating in this study did not induce this effect as has also been reported by others 45. Spheroids mimic a solid tumor in terms of cell physiology, presence of extracellular matrix and an apoptotic core 46. For this reason, we employed this model to investigate whether Dox penetration depth into a dense structure of cells is influenced by different heating conditions 47, 48. BFS-1 spheroids showed a similar response in Dox uptake as the 2D model when different HT protocols were applied. However, it also showed that if cells are closely packed, the drug does not penetrate deep into the structure beyond the first few layers of cells. Neither the spatial distribution nor the penetration depth could be improved by HT in tumor spheroids. A comparative study using B16 cells was not possible since B16 cells did not form spheroids. The latter might be caused by the lack of a substantial cell-cell adherence, which was also observed in ex vivo examination of B16 tumors described later in this section.

At this stage we have only shown the potential of local chemotherapy and HT in vitro. However, the described features are only a small part of the factors that have to be considered for drug delivery to solid tumors. Therefore, we performed a therapeutic study as well as in vivo imaging and extensive ex vivo investigation on B16 and BFS-1 tumors to better understand the factors that could have played a role in various therapeutic responses. For both tumor types, a 1-step approach where TSLDox is i.v. administered during HT42 gave a significant therapeutic response, whereas a 2-step approach which relied on TSLDox accumulation in a preheated (HT41) tumor followed by a second HT42 step to induce drug release did not show a therapeutic effect. The SPECT/CT imaging in this case was particularly valuable to follow the TSL accumulation in B16 and BFS-1 tumors. The SPECT data were used for fitting a two compartment model which describes tumor uptake of the liposomal carrier as well as the intraliposomal Dox concentration in the tumor taking the blood kinetic and pharmacokinetic parameters of TSLDox into account 39. For both tumors and regardless of applying HT41 beforehand, the maximum concentration of liposomes was reached approx. 4 h p.i., when the second HT42 step was applied. The B16 tumors showed a significantly higher liposomal uptake compared to the BFS-1 tumor with ca. two fold higher kin and kret parameters reflecting a higher intrinsic EPR effect for the B16 model. Interestingly, 1 hour of HT41 induced the same effect in both tumors leading to a 1.66 times increase in kin and kret and thus maintaining the two fold higher uptake of TSLs in B16 compared to BFS1 tumors.

However, calculations suggested that maximum intraliposomal Dox concentrations were already reached 2 h p.i., and declining to zero within 20 h due to leakage from the TSLs. These data imply that a more favorable time point for the second HT42 step is ca. 2-3 h p.i. 36. Based on our calculations, the intraliposomal Dox reached concentrations of 1.7 % ID/cc for B16 and 0.6 % ID/cc Dox for BFS-1 at the moment of the second HT42 step (i.e. after 4 h) at normal temperature conditions, and 3.0 % ID/cc and 1.5 % ID/cc Dox with a preceding HT41 treatment. These concentrations are lower compared to typical values found for a 1-step delivery approach 49, which provides an explanation for the lack of a significant therapeutic response in a 2-step drug delivery protocol.

Finally, we performed histological analysis of excised tumors and investigated factors that may cause the differences in TSL uptake and the intrinsically higher EPR effect found in B16 and BFS-1 tumors. B16 tumors grew more aggressively than BFS-1, reaching volumes of 200 mm3 in 7-14 and 14-21 days after inoculation, respectively. Especially in preclinical models, fast growing tumors show higher structural and functional abnormalities of the vasculature, thereby increasing the odds for a high EPR effect 1, 50, 51. The mean vessel density was similar for B16 and BFS-1, however the morphology of B16 vessels appeared more tortuous and overall larger in size. Next to the growth rate and vascular properties, we also observed noticeable differences in cell packing and organization, which is important for the penetration depth of extravasated compounds into the tumor interstitium 47, 52, 53. H&E staining showed less dense cellular packing with gaps in the B16 tumor tissue, whereas BFS-1 showed a higher density and no gaps. Therefore, the finding that BFS-1 cells could form spheroids while B16 cells did not, might be indicative for cell packing and organization in an actual tumor. In vivo, cell packing density and organization is, among other reasons, depends on the presence of a well-defined extracellular matrix. Analysis on the extracellular matrix by MSB staining and quantitative collagen IV immunostaining showed that B16 tumors have an almost completely absent extracellular matrix, whereas BFS-1 tumors had a more mature extracellular matrix. These findings suggest that the immature interstitium of the B16 tumor could have played a role in facilitating a higher EPR, confirming previously published results 54. Histological analysis and quantitative TUNEL staining also indicated a much higher amount of apoptosis in the B16 tumors than in the BFS-1 tumors, which is typically associated with a more pronounced EPR effect 55, 56. The HT41 induced increase of apoptosis was significant for the sectioned BFS-1 tumors. While our study is in line with earlier findings showing that HT increases vascular permeability and promotes extravasation of nanoparticles 29-31, our histology data also suggest that substantial HT41 induced apoptosis can further aid EPR.

In summary, we have shown that HT can aid in drug delivery by making cells more susceptible for Dox uptake, increasing the EPR-mediated uptake of liposomal drugs and by providing a trigger for drug release from TSLDox. All above factors play a pivotal role in the here employed 2-step delivery scheme. However, the actual amount of Dox delivered in a 2-step approach is determined by liposomal uptake and stability of the formulation and can therefore never exceed the liposomal uptake (in %ID/g). This study has shown that preheated B16 and BFS-1 tumors accumulated a maximum of 9.8 %ID/cc and 5.0 %ID/cc of the injected TSL dose, while the intraliposomal Dox concentration only reached 3 and 1.5 %ID/cc at 4 hours p.i. respectively. These Dox concentrations appeared insufficient to induce a noticeable therapeutic response. The 1-step intravascular drug release seems to be advantageous, since the injected TSLDox provide a high plasma concentration of Dox exposing the tumor to a high area under the curve over the time span of HT. Furthermore, the HT induced increase in Dox uptake by tumor cells may lead in both delivery schemes to a higher intracellular concentration.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1-S4.

Video S1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge NanoNextNL Project 03D.02 for funding. Furthermore, we would like to thank Erik de Blois, Stuart Koelewijn and Jan de Swart from the departments of Nuclear Medicine and Radiology of the Erasmus MC for technical support on radiolabeling of TSL and SPECT-CT experiments. We thank Gert van Cappellen from the Optical Imaging Center, Erasmus MC, for advice on quantification of fluorescence microscopy data.

Abbreviations

- TSL

thermosensitive liposome

- HT

hyperthermia

- NT

normothermia

- Dox

Doxorubicin

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention.

References

- 1.Jain RK. Normalization of Tumor Vasculature: An Emerging Concept in Antiangiogenic Therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagy JA, Chang SH, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF. Why are tumour blood vessels abnormal and why is it important to know? Br J Cancer. 2009;100:865–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobbs SK, Monsky WL, Yuan F, Roberts WG, Griffith L, Torchilin VP. et al. Regulation of transport pathways in tumor vessels: role of tumor type and microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4607–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashizume H, Baluk P, Morikawa S, McLean JW, Thurston G, Roberge S. et al. Openings between defective endothelial cells explain tumor vessel leakiness. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1363–80. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi H, Watanabe R, Choyke PL. Improving conventional enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects; what is the appropriate target? Theranostics. 2013;4:81–9. doi: 10.7150/thno.7193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science. 2004;303:1818–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1095833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabizon A, Catane R, Uziely B, Kaufman B, Safra T, Cohen R. et al. Prolonged circulation time and enhanced accumulation in malignant exudates of doxorubicin encapsulated in polyethylene-glycol coated liposomes. Cancer Res. 1994;54:987–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Barenholz Y. Pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin - Review of animal and human studies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:419–36. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laginha KM, Verwoert S, Charrois GJR, Allen TM. Determination of doxorubicin levels in whole tumor and tumor nuclei in murine breast cancer tumors. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11:6944–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yatvin MB, Weinstein JN, Dennis WH, Blumenthal R. Design of liposomes for enhanced local release of drugs by hyperthermia. Science. 1978;202:1290–3. doi: 10.1126/science.364652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Needham D, Anyarambhatla G, Kong G, Dewhirst MW. A new temperature-sensitive liposome for use with mild hyperthermia: characterization and testing in a human tumor xenograft model. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, ten Hagen TL, Hossann M, Suss R, van Rhoon GC, Eggermont AM. et al. Mild hyperthermia triggered doxorubicin release from optimized stealth thermosensitive liposomes improves intratumoral drug delivery and efficacy. J Control Release. 2013;168:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Smet M, Langereis S, van den Bosch S, Grull H. Temperature-sensitive liposomes for doxorubicin delivery under MRI guidance. J Control Release. 2010;143:120–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindner LH, Eichhorn ME, Eibl H, Teichert N, Schmitt-Sody M, Issels RD. et al. Novel temperature-sensitive liposomes with prolonged circulation time. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2168–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Smet M, Heijman E, Langereis S, Hijnen NM, Grull H. Magnetic resonance imaging of high intensity focused ultrasound mediated drug delivery from temperature-sensitive liposomes: an in vivo proof-of-concept study. J Control Release. 2011;150:102–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Celsion. Phase 3 Study of ThermoDox With Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) in Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) ClinicalTrialsgov NCT00617981; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celsion. Study of ThermoDox With Standardized Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) for treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) (OPTIMA) ClinicalTrialsgov NCT02112656; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overgaart J. Effect of hyperthermia on malignant cells in vivo: A review and a hypothesis. Cancer. 1977;39:2637–46. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2637::aid-cncr2820390650>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song CW. Effect of Local Hyperthermia on Blood-Flow and Microenvironment - a Review. Cancer Research. 1984;44:4721–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calabro A, Singletary SE, Tucker S, Boddie A, Spitzer G, Cavaliere R. In vitro thermo-chemosensitivity screening of spontaneous human tumors: significant potentiation for cisplatin but not adriamycin. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:385–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakaguchi Y, Stephens LC, Makino M, Kaneko T, Strebel FR, Danhauser LL. et al. Apoptosis in tumors and normal tissues induced by whole body hyperthermia in rats. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5459–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yarmolenko PS, Moon EJ, Landon C, Manzoor A, Hochman DW, Viglianti BL. et al. Thresholds for thermal damage to normal tissues: an update. Int J Hyperthermia. 2011;27:320–43. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2010.534527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hildebrandt B, Wust P, Ahlers O, Dieing A, Sreenivasa G, Kerner T. et al. The cellular and molecular basis of hyperthermia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;43:33–56. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Issels RD, Lindner LH, Verweij J, Wust P, Reichardt P, Schem BC. et al. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy alone or with regional hyperthermia for localised high-risk soft-tissue sarcoma: a randomised phase 3 multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:561–70. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70071-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bates DA, Mackillop WJ. Hyperthermia, adriamycin transport, and cytotoxicity in drug-sensitive and -resistant Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5477–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawai H, Minamiya Y, Kitamura M, Matsuzaki I, Hashimoto M, Suzuki H. et al. Direct measurement of doxorubicin concentration in the intact, living single cancer cell during hyperthermia. Cancer. 1997;79:214–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970115)79:2<214::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang SK, Stauffer PR, Hong K, Guo JW, Phillips TL, Huang A. et al. Liposomes and hyperthermia in mice: increased tumor uptake and therapeutic efficacy of doxorubicin in sterically stabilized liposomes. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2186–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Characterization of the effect of hyperthermia on nanoparticle extravasation from tumor vasculature. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3027–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, ten Hagen TLM, Bolkestein M, Gasselhuber A, Yatvin J, van Rhoon GC. et al. Improved intratumoral nanoparticle extravasation and penetration by mild hyperthermia. Journal of Controlled Release. 2013;167:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Smet M, Langereis S, van den Bosch S, Bitter K, Hijnen NM, Heijman E. et al. SPECT/CT imaging of temperature-sensitive liposomes for MR-image guided drug delivery with high intensity focused ultrasound. J Control Release. 2013;169:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matteucci ML, Anyarambhatla G, Rosner G, Azuma C, Fisher PE, Dewhirst MW. et al. Hyperthermia increases accumulation of technetium-99m-labeled liposomes in feline sarcomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3748–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez Secord A, Jones EL, Hahn CA, Petros WP, Yu D, Havrilesky LJ. et al. Phase I/II trial of intravenous Doxil and whole abdomen hyperthermia in patients with refractory ovarian cancer. Int J Hyperthermia. 2005;21:333–47. doi: 10.1080/02656730500110155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vujaskovic Z, Kim DW, Jones E, Lan L, McCall L, Dewhirst MW. et al. A phase I/II study of neoadjuvant liposomal doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and hyperthermia in locally advanced breast cancer. Int J Hyperthermia. 2010;26:514–21. doi: 10.3109/02656731003639364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, ten Hagen TL, Haeri A, Soullie T, Scholten C, Seynhaeve AL. et al. A novel two-step mild hyperthermia for advanced liposomal chemotherapy. J Control Release. 2014;174:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartlett GR. Phosphorus Assay in Column Chromotography. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1959;234:466–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagelkerke A, Bussink J, Sweep FC, Span PN. Generation of multicellular tumor spheroids of breast cancer cells: how to go three-dimensional. Anal Biochem. 2013;437:17–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lokerse WJM, Kneepkens ECM, ten Hagen TLM, Eggermont AMM, Grüll H, Koning GA. In depth study on thermosensitive liposomes: Optimizing formulations for tumor specific therapy and in vitro to in vivo relations. Biomaterials; 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eddy HA. Alterations in tumor microvasculature during hyperthermia. Radiology. 1980;137:515–21. doi: 10.1148/radiology.137.2.7433685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hahn GM, Strande DP. Cytotoxic effects of hyperthermia and adriamycin on Chinese hamster cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57:1063–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/57.5.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herman TS. Temperature dependence of adriamycin, cis-diamminedichloroplatinum, bleomycin, and 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea cytotoxicity in vitro. Cancer Res. 1983;43:517–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagaoka S, Kawasaki S, Sasaki K, Nakanishi T. Intracellular uptake, retention and cytotoxic effect of adriamycin combined with hyperthermia in vitro. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1986;77:205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rice GC, Hahn GM. Modulation of adriamycin transport by hyperthermia as measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1987;20:183–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00570481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moriyama-Gonda N, Igawa M, Shiina H, Wada Y. Heat-induced membrane damage combined with adriamycin on prostate carcinoma PC-3 cells: correlation of cytotoxicity, permeability and P-glycoprotein or metallothionein expression. Br J Urol. 1998;82:552–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirschhaeuser F, Menne H, Dittfeld C, West J, Mueller-Klieser W, Kunz-Schughart LA. Multicellular tumor spheroids: an underestimated tool is catching up again. J Biotechnol. 2010;148:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mikhail AS, Eetezadi S, Ekdawi SN, Stewart J, Allen C. Image-based analysis of the size- and time-dependent penetration of polymeric micelles in multicellular tumor spheroids and tumor xenografts. Int J Pharm. 2014;464:168–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim TH, Mount CW, Gombotz WR, Pun SH. The delivery of doxorubicin to 3-D multicellular spheroids and tumors in a murine xenograft model using tumor-penetrating triblock polymeric micelles. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7386–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hijnen N, Langereis S, Grull H. Magnetic resonance guided high-intensity focused ultrasound for image-guided temperature-induced drug delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2014;72:65–81. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dvorak HF, Nagy JA, Dvorak JT, Dvorak AM. Identification and characterization of the blood vessels of solid tumors that are leaky to circulating macromolecules. Am J Pathol. 1988;133:95–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lammers T, Kiessling F, Hennink WE, Storm G. Drug targeting to tumors: principles, pitfalls and (pre-) clinical progress. J Control Release. 2012;161:175–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGuire S, Yuan F. Improving interstitial transport of macromolecules through reduction in cell volume fraction in tumor tissues. Nanomedicine. 2012;8:1088–95. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:583–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Netti PA, Berk DA, Swartz MA, Grodzinsky AJ, Jain RK. Role of extracellular matrix assembly in interstitial transport in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2497–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Enhancement of paclitaxel delivery to solid tumors by apoptosis-inducing pretreatment: effect of treatment schedule. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:1035–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heneweer C, Holland JP, Divilov V, Carlin S, Lewis JS. Magnitude of Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect in Tumors with Different Phenotypes: Zr-89-Albumin as a Model System. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:625–33. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.083998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1-S4.

Video S1.