You let us die here,” a resident of the isolated Bella Bella community in remote British Columbia once said to Dr Stuart Iglesias, “but you don’t let us be born here.”

This short statement, made not so long ago to rural family physician Iglesias, who is also an economist by early training, has stuck with him. Has fueled a passion.

“It used to be that a birth in a First Nations community like Bella Bella was a knock-your-socks-off event,” recalls Dr Iglesias. “Flags were raised. An hour after my own wife, a teacher, gave birth in Bella Bella, her entire grade 1 class came to visit. It was a community celebration.”

Now, according to other physicians and researchers like Drs Robert Woollard and Jude Kornelsen, who work in partnership with Dr Iglesias, a lack of system-wide approaches and analysis has resulted in a rural maternity care crisis in British Columbia and across the country. And there are currents of economic conversations that swirl through the rural maternity care crisis, currents all 3 are eager to unsettle.

“Services have been disappearing,” observes Woollard, also a long-time family physician and former Head of the Department of Family Practice at the University of British Columbia. “They’re disappearing by default, a result of non-decisions. There is really limited knowledge about the implications of these disappearances. In Canada, we take pride in the availability of health care services, but they’re becoming less available in rural areas.”

Dr Jude Kornelsen, Co-Director of the UBC Centre for Rural Health Research in the Department of Family Practice, agrees part of the challenge is the amorphous nature of conversations about rural maternity care: “Mostly it’s an outcome of centralization, which has a benevolent intent. At the same time everyone wanted cost containment. The 1990s saw this move toward regionalizing services. We thought delivering specialized services outside the biggest of cities would bring things closer to home. But maternity care isn’t a specialized service! And we didn’t ask about what kind of evidence was fueling these decisions.”

“A lot of this is about a century-long uncritical love affair with specialization,” agrees Woollard. “We seem unable to take a systems view. We don’t see how pieces fit together. The mantra in British Columbia is ‘closer to home’—but this is a kind of false democratization. Regionalization was a political narcotic, convenient to politicians, but it resulted in centralization to regional centres and loss of decision making and services at the local level. In my rural town of Clearwater, BC, we used to have almost 100 births a year. In a 10-bed hospital. I remember 5 babes and 5 mothers in there at a time. At Christmas! We were told that a hospital without specialized electronic fetal monitoring shouldn’t handle deliveries. This at a time when clear evidence showed that routine fetal monitoring actually increased newborn mortality and maternal morbidity. In my first year delivering babies in a large tertiary hospital after moving to Vancouver, I spent time removing fetal monitors from my moms in labour—it is not only the politicians who are addicted to technology! We fought this battle in Victoria and won—but over the years, as decision making moved to Kelowna, obstetrical services were bled away to larger regional hospitals leaving small towns unsupported. This is in spite of the evidence, gathered by Jude, Stu, and others, that distributed care is not only desirable, but equally safe.”

“The separation of primary, secondary, and tertiary care did a great disservice to rural care,” acknowledges Iglesias. “The love affair with specialization and the erosion of generalism has meant that urban specialists control the training and delivery of secondary care—including maternity care and operative delivery. The story that those of us working in the area of rural maternity care are trying to tell is not just a story about general surgery and obstetrics by family physicians. It’s a story about people trying to effect social change, a story about a tide that is trying to rise high enough to change an entire landscape.”

Changing landscapes means changing ideas, changing worldviews and entire ways of approaching questions or decision-making processes. Iglesias, Woollard, and Kornelsen all agree that for this kind of systemic transformation to occur, 4 groups of people have to come together, build relationships, understand systems thinking, and learn to deliberate differently. “Science doesn’t bring about change,” chuckles Iglesias. “It can support change, but we need to build relationships and networks. To move new policy forward, we need academics, care providers, policy makers, and community people all talking to each other.”

For Kornelsen, the evidence that these 4 groups should be talking about has to include lived experiences of those on the front lines—the families who can’t be at the bedside of loved ones during one of life’s most miraculous moments: a mother giving birth to her baby. “We can no longer make decisions without evidence that includes the voices of community members. We need the people making decisions to witness the experience of service loss. To witness that we are talking about questions of social justice, of equitable access to care, care that rural people just aren’t getting.”

“This is also not about ‘rural’ being understood as ‘small urban,’” Woollard adds. “It’s about asking how policies are manifest in small isolated places, how they are lived and felt.”

For all three, the crisis in rural maternity care is both a deeply personal issue and an issue with national and global implications. For each of them, as Kornelsen summarized, births and maternity care are the bedrock of communities, the things that ground everything else—babes and mothers, together, bringing and embodying life giving in small, isolated, or rural communities. That is the cultural integrity of those places. The lifeblood of all else.

“I know Australia is struggling with these very same issues,” says Kornelsen from her rural home on Salt Spring Island—where she moved in 1999 and was astounded to learn of the tenuousness of the local primary, midwifery-led maternity service. “I was blown away. It was very personal. And there was so little written about it.”

“There is no nation in the world,” adds Woollard, “without a growing divergence between rural and urban people’s well-being. This is a social justice issue. I see it in Nepal, for instance, but I have lived it. My wife is a South Carolina girl. I grew up in rural Alberta. We never thought we were ‘smart’ enough to raise our kids in the city—but now I take a lot from that statement that the city has a lot to learn from the country, if the city would just shut up and listen.”

“There is still a lot of work to be done,” concludes Iglesias. “But never in 35 years have I seen a tide like this one, a rising tide of change. This is the time. We need to pull the damn sword out of the rock.”

BACKGROUND PHOTO: Aerial view of Bella Bella, BC.

Collin Reid and son Kaiis at baby uplifting ceremony. “Socially and culturally it’s important for our children to be born in their homeland.”

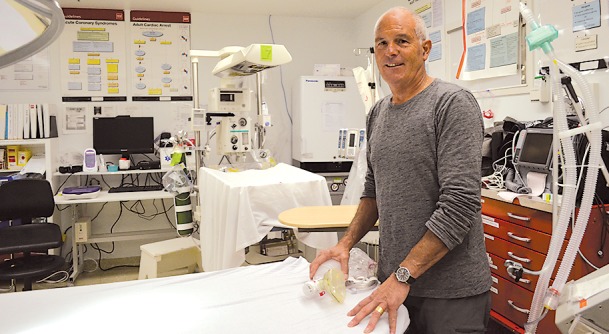

Dr Iglesias in the operating room that closed in 2000, followed in 2002 by the closure of the maternity care program. “Rural surgery programs sustain community maternity care.”

Leona Humchitt and granddaughter Maggie at baby uplifting ceremony. “I refused to leave so my babies were born in the hospital in Bella Bella.”

Flora Innes and daughter Maggie at baby uplifting ceremony. “At great cost to my family they flew to Vancouver to be with me when my baby was born.”

Danya Brown and son Kaiis. “The uplifting ceremony introduces and connects our babies to the community so everyone can support them growing up.”

Pauline McNaughton and daughter Tess. “Our families used to gather at the hospital to welcome babies into the world.”

Chief Wigvilba Wakas uplifting nephew Nathaniel.

PHOTO (RIGHT) Drummers (left to right) Ian Reid with baby Kaiis, Carl Wilson, Kevin Starr, Richard Green, and Dayton White.

PHOTOS (ABOVE) A killer whale swims into the harbour in Bella Bella, BC; the hospital can be seen in the background (left); Bella Bella’s hospital (right).

PHOTOGRAPHER Brenda Humchitt, Bella Bella, BC

Dr Jude Kornelsen

Dr Bob Woollard

Dr Stuart Iglesias

Footnotes

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de juillet 2016 à la page e415.

Dr Kornelsen is a health services researcher and Associate Professor in the Department of Family Practice at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Co-Director of the Centre for Rural Health Research, Director of the Applied Policy Research Unit, and Honorary Associate Professor in the Medical School at Sydney University in Australia, and she is seconded (part time) to the BC Ministry of Health’s Rural, Remote and Aboriginal Health Branch for April 2016 to March 2017. Dr Woollard is Associate Director of the Rural Coordination Centre of BC, a practising family physician, and Professor in the Department of Family Practice at the University of British Columbia. Dr Iglesias is a rural family physician who lives in Bella Bella, BC, and a health services researcher. All were authors on the “Joint Position Paper on Rural Surgery and Operative Delivery,” which reviews the evidence and documents the consensus that the sustainability of rural maternity care is linked to the preservation of robust local surgery programs. These small-volume, rural surgery programs, often delivered by family physicians with enhanced surgical skills, are both safe and cost-effective. Where they have closed, the maternity services usually close soon after. The surgical program in Bella Bella closed in 2000. The local maternity care program closed in 2002.

The Cover Project The Faces of Family Medicine project has evolved from individual faces of family medicine in Canada to portraits of physicians and communities across the country grappling with some of the inequities and challenges pervading society. It is our hope that over time this collection of covers and stories will help us to enhance our relationships with our patients in our own communities.